Abstract

Simple Grignard procedures provide methallylboranes 1a and 1b in enantiomerically pure form from air-stable precursors in 98% and 95% yields, respectively. These reagents add smoothly to aldehydes and methyl ketones, respectively, providing branched 2°-(6, 69–89%, 94–99% ee) and 3°-(10, 71–87%, 74–96% ee) homoallylic alcohols.

The asymmetric allylboration of aldehydes remains as one of the most powerful processes for the preparation of nonracemic 2°-homoallylic alcohols.1 In 1978, R. W. Hoffmann1a,c reported the first enantioselective synthesis of branched 2°-homoallylic alcohols employing a methallyl derivative of his camphor-derived boronic esters. Unfortunately, low enantioselectivity is generally observed with these reagents (40–76% ee). Brown’s diisopinocampheylborane reagents proved to be more selective (90–96% ee), but the preparation of these reagents from high-purity air-sensitive organoborane precursors through organolithium procedures presents operational difficulties.1d,o Moreover, these reagents are ineffective for the allylation of ketones.1e A variety of alternative processes are now available for these types of “allylation” processes,2 but for ketone substrates, the only successful methallylation was recently reported employing tetrakis-(methallyl)tin and a (R)-H8-BINOL/Ti catalyst.3 This method uses six (6) equiv of the toxic methallyltin moiety, a large catalyst loading (30 mol %) and exhibits modest to good enantioselectivity (46–90% ee). Since asymmetric methallylation is an important synthetic process,4 we felt that a better, more selective and user-friendly process would represent an important advance. We envisaged that the methallylation of both aldehydes and ketones could be markedly improved through the use of the 10-substituted-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]decanes which are easy to handle, effectively recovered and recycled, and are available in both enantiomeric forms.

Recently, we reported the synthesis of the B-allyl-10-TMS- and -10-Ph-BBD systems (2) and their highly selective additions to aldehydes5 and ketones,6 respectively. The corresponding B-methallyl reagents 1 were envisaged as very attractive alternatives for the methallylboration of either aldehydes or ketones, depending upon the choice of the 10-substituent employed.

The air-stable crystalline pseudoephedrine (PE) complexes 4a serve as efficient precursors to 2a (98%) through simple Grignard procedures.5 However, the analogous process with 4a and methallylmagnesium chloride (0.5 M in THF) proved to be both sluggish and inefficient. Fortunately, the more reactive B-OMe derivatives 3a, which are readily prepared from 2a (87%),5a provide an efficient entry to 1a through this Grignard method (98%) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Preparation of Methallylborane 1.

Reagents 1a react smoothly with aldehydes to yield pure 3-methyl homoallylic alcohols 6 efficiently (69–89%) with excellent selectivities (94–99% ee) (Scheme 2, Table 1). The product ee’s were determined by their conversion to their Alexakis esters and analysis through 31P NMR.7 Similar to allylboration,5 this process is quite general, being effective for alkyl, aryl, substituted aryl, heteroaryl, and unsaturated aldehydes. Our protocol includes the isolation of the borinic ester intermediates 5 in essentially quantitative yields following the removal of the solvents. A non-oxidative work-up procedure was employed which permits the recovery of the air-stable pseudoephedrine (PE) complexes 4a (62–78%), which can be converted back to 1a (Scheme 1).

Scheme 2.

Asymmetric Allylboration of Aldehydes with 1a.

Table 1.

Methallylboration of Aldehydes with 1a

| R in RCHO | series | 1a | 4a (%) | 6 (%) | eea % abs configc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph d | a | S,R | 73,75 | 78,80 | 95, (S),(R) |

| 4-MeOC6H4 | b | S | 66 | 78 | 98b, (S) |

| 4-NO2C6H4 | c | R | 66 | 69 | 99, (R) |

| 2-ClC6H4 | d | R | 70 | 89 | 94, (R) |

| Pyridyl | e | R | 62 | 88 | 96, (R) |

| i-Pr | f | S | 74 | 75 | 97, (S) |

| t-Bu | g | R | 65 | 73 | 94, (R) |

| trans-Crotyl | h | R | 78 | 85 | 94, (R) |

Enantiomeric excesses were determined by conversion to Alexakis esters and 31P NMR analysis.7

Enantiomeric excess was determined by 13C NMR analysis of the Mosher ester.

The absolute configuration of the alcohols was determined by a direct comparison of optical rotations obtained to those reported in the literature.1c–d,2b

This run was performed with both (+)-1Sa and (−)-1Ra.

The competitive reaction of 1a and 2a with benzaldehyde (1:1:1) was conducted at −78 °C. This reveals that 2a is only slightly more reactive than 1a (i.e., 1.3:1.0), a result which is likely to be steric in origin.

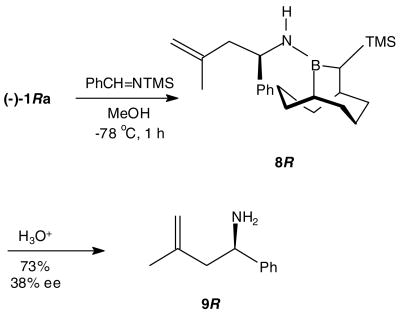

Homoallylic amines provide important building blocks for the synthesis of numerous nitrogen containing natural products.8 While the methallylboration of N-metallo imines is unknown,9 the corresponding allylboration process has been extensively studied.10,11,12 We chose to examine this process through the generation of N-H benzaldimine with MeOH (1 equiv) from its N-TMS precursor in the presence of 1a in THF at −78 °C. After 1 h, the formation of the aminoborane 8 was complete as determined by 11B NMR (δ 46). Acidic hydrolysis (2 M HCl) followed by a basic work-up affords the homoallylic amine 9 (73%), in only modest enantioselectivity (38% ee) (Scheme 3). While disappointing, the lowered observed selectivities for this and related additions to aldimines vs aldehydes appears to be a general phenomenon attributable to the larger relative size of NH vs O.12

Scheme 3.

Asymmetric Allylboration of Benzaldimine with 1a.

In contrast to the sluggish reaction of methallylmagnesium chloride with 4a, this Grignard reagent does readily add to the crystalline pseudoephedrine complex,6 (+)-4Rb, to provide pure B-methallyl-10-Ph-9-BBD ((−)-1Rb) directly in excellent yield (95%) (Scheme 4). The enantiomer, (+)-1Sb, was similarly prepared from the corresponding N-methylpseudoephedrine complex, (+)-4′Sb.6 The asymmetric methallylboration of representative methyl ketones was examined with 1b. These reagents (−)-1Rb and (+)-1Sb undergo clean addition even to hindered methyl ketones (entry 3d) in ≤3 h at −78 °C providing the desired 3°-carbinols 10 with excellent enantioselectivities (74–96% ee) (Table 2). An oxidative workup (NaOH, H2O2) was normally used in this protocol. A non-oxidative procedure employing N-methylpseudoephedrine was developed for the 10Sa example resulting in a 76% yield of recovered (+)-4′Sb. Similarly, for 10Rb, a pseudoephedrine workup gave crystalline (+)-4Rb in 71% yield.

Scheme 4.

Asymmetric Allylboration of Ketones with 1b.

Table 2.

Methallylboration of Ketones with 1b

| R in RCOCH3 | 10 | 1b | yield % | eea % abs configb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph | a | S | 87 (80)c | 88, S |

| 4-NO2C6H4 | b | R | 71 (69)c | 93, R |

| trans-PhCH=CH | c | S | 81 | 74, S |

| t-Bu | d | S | 75 | 96, S |

Enantiomeric excesses were determined by conversion to Alexakis esters and 31P NMR.7

The absolute configuration of the alcohols was determined by a direct comparison of optical rotations obtained to those reported in the literature.3a

Yields in parentheses for 10Sa and 10Rb were obtained employing a non-oxidative workup (The complexes (+)-4′Sb and (+)-4Rb were also recovered in 76% and 71%, respectively).

The asymmetric addition of acetone derived enolates to aldehydes occurs with low enantioselectivity.13 The product β-hydroxy methyl ketones are valuable intermediates in the total synthesis of macrolide and polyether antibiotics.14 An alternative to the ineffective aldol route to β-hydroxy methyl ketones with acetone enolates was introduced by Hoffmann1b through the ozonolysis of 6. Very recently, Walsh showed that this process was effective for 10.3a With the higher selectivities observed with 1 and 10, we chose to demonstrate the synthetic value of this transformation further with simple examples and to reconfirm the absolute stereochemistry of 6 and 10 (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Ozonolysis of β-Methyl Homoallylic Alcohols.

In summary, the new BBD reagents 1 are efficiently prepared in either enantiomeric form through simple Grignard procedures that employ air-stable organoborane precursors. Exceeding the selectivities observed with other reagents and processes, 1 provides either enantiomer of branched 2° (6, 69–89%) and 3°-homoallylic alcohols (10, 71–87%) with predictable stereochemistry (see Fig. 1)5,6 and remarkable enantioselectivity (94–99% and 74–96% ee, respectively). Thus, for the first time, one system can be modified for the effective methallylation of either aldehydes or ketones. This new method can be used with either an oxidative or non-oxidative workup, the latter process providing the recovered chiral borane as an air-stable and recyclable complex 4. Ozonolysis of 6 and 10 provides β-hydroxyalkyl methyl ketones 7 and 11 efficiently in high enantiomeric purity.

Figure 1.

Proposed models for the most energetically favorable pre-transition state complexes which explain the observed stereochemistry in the methallylboration of RCHO with 1a (A) and RCOMe with 1b (B).

Experimental Section

B-Methallyl-10R-trimethylsilyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]decane ((−)-1Ra)

A solution of (−)-3R (0.71 g, 3.0 mmol) in hexane (12 mL) was cooled to 0 °C and a solution of methallylmagnesium chloride (7.8 mL of 0.5 M in THF) was added dropwise. The solution was allowed to reach room temperature and was stirred for 1 h. Then the reaction mixture was cooled to −78 °C and quenched with TMSCl (0.5 equiv). Using standard techniques to prevent the exposure of the borane to the open atmosphere, the solution was concentrated under vacuum, the residue was washed with pentane (4 x10 mL) and these washings were filtered through a celite pad. Concentration gives 0.77 g (98%) of (−)-1Ra. 1H NMR (C6D6, 300 MHz) δ0.23 (s, 9H), 1.02–1.76 (m, 15H), 1.80 (s, 3H), 2.23 (m, 3H), 4.75 (s, 1H), 4.92 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, C6D6) δ 1.9, 22.2, 25.4, 25.9, 26.2, 29.2, 31.5, 34.2, 34.9, 40.0, 40.9, 110.0, 145.0; 11B NMR (CDCl3) δ 83.7; [α]D23 = −22.6° (c 1.24, C6D6). B-Methallyl-10S-trimethylsilyl-9-borabicyclo-[3.3.2]decane ((+)-1Sa) is prepared by the same procedure starting with (+)-3S. [α]D23 = +22.3 (c = 1.24, C6D6). HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. for C16H31BSi, 263.2368 found 263.2369 m/z.

Representative procedure for the allylboration of aldehydes with 1a. (−)-(R)-3-Methyl-1-(2-chlorophenyl)-3-buten-1-ol (6Rd)

A solution of (−)-1Ra (0.79 g, 3 mmol) in THF (3 mL) was cooled to −78 °C and 2-chlorobenzaldehyde ( 0.42 g, 3.0 mmol) was added dropwise. After 3 h, the solvents were removed under vacuum to yield 1.15 g (95%) of the corresponding borinate 5Rd. The (1S,2S)-(−)-pseudoephedrine (0.50 g, 3.0 mmol) and acetonitrile (7 mL) were added and the mixture was heated at reflux temperature for 2 h. The crystals were separated and washed with pentane (3 × 10 mL) to yield 0.78 g (70%) of (+)-4Ra. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (9:1, hexane: Et2O) to obtain 0.52 g (88 %) of 3-methyl-1-(2-chlorophenyl)-3-buten-1-ol (6Rd). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 1.86 (s, 3H), 2.23 (dd, J = 13.9 Hz, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 2.52–2.60 (m, 2H), 4.92 (d, J = 18.7 Hz, 2H), 5.21 (dd, J = 9.7 Hz, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.34 (m, 3H), 7.61 (dd, J = 7.7 Hz, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.0, 46.6, 67.9, 114.2, 126.9, 127.1, 128.3, 129.3, 131.5, 141.4, 142.5. HRMS [M+H-H2O]+ calcd for C11H12Cl1, 179.0622, found 179.0622. The enantiomeric purity was determined by the CDA reagent developed by Alexakis using the reported procedures (31P NMR 131 (97, 6Rd), 144 (3, 6Sd)).7 [α]D25 = +58.54 (c = 1.11, CHCl3, 94% ee).

Representative Ozonolysis. (S)-4-Hydroxy-4-phenyl-2-butanone (7)

6Sa (0.14 g, 0.86 mmol) was diluted in MeOH (10 mL) and cooled to −78 °C. To this solution, ozone was bubbled until a blue color persisted (10 min) in the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was allowed to reach room temperature and the excess of ozone was removed under a N2 purge. The solution was cooled to −78 °C, dimethyl sulfide (0.13 mL) was added dropwise and the mixture was stirred overnight slowly reaching room temperature. The mixture was washed with water (3 × 5 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford 0.14 g of 7 (98%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ2.20 (s, 3H), 2.81 (dd, J = 3.6 Hz, 18.0 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (dd, J = 8.7 Hz, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 3.32 (s, broad OH, 1H), 5.15 (dd, J = 3.7 Hz, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.26–7.36 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ 30.7, 51.9, 69.8, 125.6, 127.7, 142.7, 209.0. [α]D24 = −53.2 (c 2.20, CHCl3); lit13 (R) [α]D25 = +40.9 (c 10.3, CHCl3, 57% ee) +57.1 (c 1.10, CHCl3).

(R)-3-Methyl-1-phenyl-3-buten-1-amine (9R)

A solution of (−)-1Ra (0.79 g, 3 mmol) in THF (3 mL) was cooled to −78 °C. To this solution N-TMS benzaldimine (0.62 g, 3.0 mmol)11 was added followed by dry MeOH (0.16 mL, 4 mmol). After 1 h, the reaction was warmed to room temperature and the solvents were removed under vacuum to afford the intermediate aminoborane. A solution of aqueous HCl (10 mL of 2 M) was added. The mixture stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The aqueous phase was washed with Et2O (2 × 5 mL). The resulting aqueous phase was neutralized with Na2CO3 followed by Et2O extractions (3 × 15 mL). The organic phase was then dried over MgSO4. Removal of solvent in vacuo afforded the homoallylic amine 9R (38% ee, 73% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 1.81 (s, 3H), 2.40 (ddq, J = 13.8 Hz, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 4.0 Hz, 2H), 2.42 (s, broad OH, 1H), 4.85–4.86 (m, 1H), 4.90 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.95–4.97 (m, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 22.1, 48.3, 114.9, 123.5, 126.4, 141.3, 147.1, 151.5. The enantiomeric purity was determined by the 31P NMR CDA reagent developed by Alexakis using the reported procedures.7 [α]D29 = +6.71 (c = 1.31, CHCl3, 38 % ee). HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. for C11H16N1, 162.1277 found 162.1277.

(+)-B-Methallyl-(10S)-phenyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]decane (1Sb)

To a solution of (+)-4′Sb6 (1.17 g, 3.0 mmol) in hexane (12 mL), freshly prepared methallylmagnesium chloride (9.0 mL of 0.66 M in THF) was added dropwise. The solution was allowed to stir for 2 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to −78 °C and quenched with 1.0 equiv of TMSCl. Using standard techniques to prevent the exposure of the borane to the open atmosphere, the solution was concentrated under vacuum, the residue was washed with pentane (3 × 20 mL) and these washings were filtered through a celite pad. Concentration gives 0.76 g (95%) of 1Sb. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 1.60–2.71 (m, 20H), 4.57 (s, 1H) 4.80 (s, 1H) 7.15–7.42 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 23.5, 23.6, 25.4, 26.6, 27.9, 29.1, 29.8, 34.2, 39.9, 40.4, 53.3, 109.6, 124.71, 128.1, 129.9, 144.5, 146.7. [α]D27 = +45.2 (c = 2.03, C6D6). HRMS [M]+ calcd. for C19H27B, 266.2206 found 266.2206 m/z. (−)-B-Methallyl-10R-phenyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]decane (1Rb) is prepared by the same procedure starting with (+)-4Rb (9-(1S,2S-Pseudoephedrinyl)-(10R)-phenyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]-decane).6 [α]D27 = −42.3 (c = 1.91, C6D6). Other data are essentially identical to 1Sb.

Representative procedure for the allylboration of ketones with 1b. (−)-(S)-4-Methyl-2-phenyl-4-penten-2-ol (10Sa)

A solution of (+)-1Sb (0.80 g, 3.0 mmol) in THF (3 mL) was cooled to −78 °C and acetophenone (0.36 g, 3.0 mmol) was added dropwise. After 3 h, the reaction mixture was raised to 25 °C and NaOH (2.0 mL, 3 M solution in water) was added followed by H2O2 (0.9 mL, 30 wt% in water). The biphasic mixture was refluxed for 2 h followed by an aqueous workup (3 × 15 mL of brine solution). The combined organic phase was dried over MgSO4 and filtered. The crude product was then purified by silica gel column chromatography (4:1, hexane: ethyl acetate) to obtain 0.46 g of 10Sa (87%). 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 1.44 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 2.50 (s, broad OH, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J = 13.3 Hz, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 4.84 (d, J = 44 Hz, 2H), 7.22–7.50 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 24.1, 30.5, 51.9, 73.1, 115.5, 124.7, 126.4, 127.9, 142.4, 147.8. [α]D27 = −31.2 (c 1.00, CH2Cl2, 88% ee). The enantiomeric purity was determined by the CDA reagent developed by Alexakis using the reported procedures (31P NMR δ 136.5 (94, 10Sa), 138.0 (6, 10Ra)).7 These data were in complete agreement with literature values.3a

Supplementary Material

Full experimental procedures, characterization data, selected spectra for 1–10 and derivatives (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Acknowledgments

The support of the NSF (CHE-0517194) and NIH SCORE (S06GM8102) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors wish to thank Dr. Eda Canales (Harvard University) for her help with preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This work is dedicated to Professor Alfred Hassner on the occasion of his 77th birthday.

References

- 1.Herold T, Hoffmann RW. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1978;17:768.Herold T, Schrott C, Hoffmann RW. Chem Ber. 1981;114:359.Hoffmann RW, Herold T. Chem Ber. 1981;114:375.Brown HC, Jadhav PK, Perumal PT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:5111–5114.Brown HC, Jadhav PK, Perumal PT. J Org Chem. 1986;51:432.Masamune S, Short RP. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:1892.See also: Ramachandran PV. Aldrichimica Acta. 2002;35:23. and ref. cited therein.Flamme EM, Roush WR. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13644. doi: 10.1021/ja028055j.Yakelis NA, Roush WR. J Org Chem. 2003;68:3838. doi: 10.1021/jo0341012.Gao X, Hall DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9308. doi: 10.1021/ja036368o.Morgan JB, Morken JP. Org Lett. 2003;5:2573. doi: 10.1021/ol034936z.Barrett AGM, Braddock DC, de Koning PD, White AJP, Williams DJ. J Org Chem. 2000;65:375. doi: 10.1021/jo991205x.Barrett AGM, Beall JC, Braddock DC, Flack K, Gibson VC, Salter MM. J Org Chem. 2000;65:6508. doi: 10.1021/jo000690p.Corey EJ, Yu C, Kim SS. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:5495.Brown HC, Racherla US, Liao Y, Khanna VV. J Org Chem. 1992;57:6608.

- 2.(a) Wu TR, Shen L, Chong JM. Org Lett. 2004;6:2701. doi: 10.1021/ol0490882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keck GE, Krishnamurthy D. Org Syn. 1998;75:12. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamamoto H, Ishiba A, Nakashima H, Yanagisawa A. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:4723. [Google Scholar]; (d) Soai K, Niwa S. Chem Rev. 1992;92:833. [Google Scholar]; (e) Loh TP, Zhou JR, Li XR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:9333. [Google Scholar]; (f) Pu L, Yu HB. Chem Rev. 2001;101:757. doi: 10.1021/cr000411y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Pu L. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:9873. [Google Scholar]; (h) Denmark SE, Fu J. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2763. doi: 10.1021/cr020050h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh PJ, Kim JG, Camp EH. Org Lett. 2006;7:4413. doi: 10.1021/ol061417y.See also: Källström S, Jagt Rb, Sillanpää R, Feringa BL, Minnaard AJ, Leino R. Eur J Org Chem. 2006:3826.

- 4.(a) Nelson SG, Cheung SW, Kassick AJ, Hilfiker MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13654. doi: 10.1021/ja028019k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) De Brabander JK, García-Fortanet J, Jiang X. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11254. doi: 10.1021/ja0537068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakada M, Suzuki T, Inoue M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1140. doi: 10.1021/ja021243p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgos CH, Canales E, Matos K, Soderquist JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8044. doi: 10.1021/ja043612i.(b) Available from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.

- 6.Canales E, Prasad G, Soderquist JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11572. doi: 10.1021/ja053865r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexakis A, Mutti S, Mangeney P. J Org Chem. 1992;57:1224. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Nicolaou KC, Van Delf FL, Mitchel HJ, Rodríguez RM, Rudsan F. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1999;37:1871. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schmidt U, Schmidt J. Synthesis. 1994:300. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ciufolini MA, Hermann CW, Whitmire KH, Byrne NE. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:3473. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For a recent review see: Felpin F-X, Lebreton J. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:3693.

- 10.(a) Itsuno S, Watanabe K, Koichi I, El-Shehawy A, Sarhan A. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1997:36,109. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wantanabe K, Ito K, Itsuno S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1995;6:1531. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wantanabe K, Kuroda S, Yokoi A, Ito K, Itsuno S. J Organomet Chem. 1999;581:103. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown HC, Chen GMP, Ramachandran PV. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:825. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990315)38:6<825::AID-ANIE825>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez E, Canales E, Gonzalez E, Soderquist JA. Pure Appl Chem. 2006;78:1389.Hernandez E, Canales E, Soderquist JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8712. doi: 10.1021/ja062242q.See also: Gonzalez AZ, Soderquist JA. Org Lett. 2007;9:1081. doi: 10.1021/ol070074g.

- 13.(a) Paterson I, Goodman JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:997. [Google Scholar]; (b) Matsumoto Y, Hayashi T, Ito Y. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:335. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Masamune S, Hirama M, Mori S, Ali SkA, Garvey DS. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:1568. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Daines RA, Chakraborty TK, Ogawa T, Papahatjis DP, Uenishi J. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:4660. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nicolaou KC, Daines RA, Chakraborty TK. Ogawa J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:4685. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full experimental procedures, characterization data, selected spectra for 1–10 and derivatives (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org