Abstract

Objective

To explore the scope for reducing the number of intentional injury deaths, hypothesizing that all European Union (EU) countries are able to match the experience of the country with the lowest mortality rate for intentional injuries.

Design

Intentional injury mortality data for the three last available years and denominator population estimates were obtained from the World Health Organisation mortality database for the 22 EU countries with more than one million population. To estimate the potential saving of lives, the yearly average age adjusted injury mortality rates were calculated. This issue done for children (0–14), adults (15–64), and elderly people (65 and over), both including and excluding deaths from undetermined cause.

Main outcome measures

Number of lives that might potentially be saved if all EU member states matched the lowest intentional injury rate reported by an EU member state.

Results

Over 73% of all intentional injury deaths could have been avoided if all EU countries matched the country with the lowest intentional injury mortality rate. EU member states would have suffered about 600 fewer intentional injury deaths in children, about 40 000 fewer adult deaths, and over 14 000 fewer intentional injury deaths in the elderly. This amounts to over 55 000 lives in a single year.

Conclusions

Many lives lost through injury might be saved if all countries were to achieve the lowest intentional injury mortality rates reported in the EU. How this theoretical observation might be translated into practice needs to be further explored as the international variation in intentional injury mortality rates in the EU results from a range of factors.

Keywords: epidemiology, intentional injury, mortality

Injury is a leading cause of death and disability throughout the world in all age groups under 60.1,2 Around five million people worldwide died as a result of an injury in 2000, accounting for nearly one in every 10 deaths. Of these, more than one in four were caused by an intentional injury.2

Suicide is a significant problem in the European region, outnumbering the commonest cause of unintentional injury deaths, namely road traffic injuries, and is one of the top two causes of death in young adults (aged 15–44).1 Standardized suicide rates tend to be lower in the Mediterranean countries, with higher rates reported by northern and eastern European countries, particularly Finland, Hungary, and the Baltic States.3,4,5,6 These Eastern European countries and Finland share some historical and sociocultural characteristics and have the highest suicide rates in the world for both men and women.7

Violence (other than self inflicted) comprises diverse components including interpersonal (family and intimate partner violence and community violence) and collective forms (social, political, and economic violence).8 Relatively low rates of youth homicide are found in most of western Europe while high rates are found in some south‐eastern European countries.

The varying rates of suicide within the European Union (EU) may reflect variation in the prevalence of risk factors including exposure to sunshine,9 psychiatric disease,10 levels of economic development,11 degree of social support, rapid socioeconomic change,5,8,10 and cultural attitudes.12,13,14 The contribution of preventive efforts to this variation has not been adequately assessed. This paper aims to explore the relative performance of the EU member states with regard to intentional injury mortality in an attempt to quantify the potential scope for more effective prevention.

Methods

All current EU member states were included in the study with the exception of countries with fewer than one million population (Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Malta), as small numbers may be subject to excessive random variation. The 22 countries included in the analysis were: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Mortality data for intentional injury and corresponding denominator population estimates for the relevant countries were retrieved from the mortality database of the European Office of the World Health Organisation (WHO Europe) using the respective causes of death codes of the 9th and 10th editions of the International Classification of Diseases (suicides: ICD9: E950‐E959 and ICD10:X60‐X84, Y870; homicides: ICD9: E960‐E969 and ICD10: X85‐Y09, Y871; injuries of undetermined intent: ICD9: E980‐E989 and ICD10: Y10‐Y34, Y872).

Deaths caused by legal intervention and war (ICD9: E970‐E979, E990‐E999 and ICD10: Y35‐Y36, Y890‐Y891) were excluded. Our decision to exclude such deaths was taken for two reasons. First, the numbers were relatively small (36 for the whole sample). Second, both the causal pattern and prevention strategies relating to this group are very different from those of homicide and suicide. If, for example, our analysis had included later years for the UK, casualties from the Iraq war would have been considerable and either distorted the homicide category (if included there), or would have required a separate analysis. A category of legal and war deaths is therefore desirable in future studies if their frequency is great enough to withstand excessive random variation.

Table 2 Percent potential reduction of intentional injury mortality in children aged 0–14 years per 100 000 population by cause*, excluding and including injuries of undetermined intent, and annual number of lives saved in the EU countries based on the average of the last three available years (circa 2000).

| Country | Mortality rate by cause | Without injuries of undetermined intent | With injuries of undetermined intent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide | Homicide | IUI | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | |||

| Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | ||||||||

| Greece | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Spain | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 16 | 0.3 | 15.9 | 3 | 17 | 0.3 | 19.6 | 3 |

| Italy | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 25 | 0.3 | 26.2 | 7 | 31 | 0.4 | 39.9 | 12 |

| Portugal | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 5 | 0.3 | 32.4 | 2 | 42 | 2.6 | 91.5 | 39 |

| UK | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 46 | 0.4 | 49.2 | 22 | 87 | 0.8 | 73.6 | 64 |

| Sweden | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.5 | 54.8 | 4 | 10 | 0.6 | 65.6 | 7 |

| Slovakia | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.6 | 64.9 | 5 | 14 | 1.4 | 83.6 | 12 |

| Ireland | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.6 | 65.4 | 3 | 7 | 0.8 | 73.6 | 5 |

| Slovenia | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.6 | 65.5 | 2 | 3 | 0.7 | 69.7 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 19 | 0.6 | 65.8 | 12 | 20 | 0.7 | 68.2 | 14 |

| France | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 81 | 0.7 | 69.5 | 56 | 138 | 1.3 | 82.4 | 113 |

| Denmark | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.8 | 71.5 | 5 | 7 | 0.8 | 71.5 | 5 |

| Germany | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 107 | 0.9 | 74.1 | 79 | 141 | 1.1 | 80.4 | 114 |

| Poland | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 68 | 0.9 | 75.7 | 51 | 105 | 1.4 | 84.7 | 89 |

| Czech Republic | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 15 | 0.9 | 75.7 | 12 | 24 | 1.4 | 84.7 | 20 |

| Austria | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 14 | 1.1 | 80.1 | 11 | 14 | 1.1 | 80.5 | 12 |

| Belgium | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 21 | 1.2 | 81.0 | 17 | 25 | 1.4 | 84.1 | 21 |

| Finland | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.2 | 81.4 | 9 | 11 | 1.2 | 81.4 | 9 |

| Hungary | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 24 | 1.6 | 85.9 | 21 | 26 | 1.7 | 86.8 | 23 |

| Lithuania | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 13 | 1.9 | 88.6 | 12 | 19 | 3.0 | 92.7 | 17 |

| Estonia | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 5 | 2.1 | 89.4 | 5 | 6 | 2.6 | 91.4 | 6 |

| Latvia | 0.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 11 | 2.8 | 92.2 | 10 | 15 | 4.3 | 94.8 | 15 |

| EU | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 516 | 0.7 | 67.5 | 348 | 767 | 1.0 | 78.4 | 601 |

*Deaths due legal intervention or war operations are excluded.

†Bold numbers indicate a statistically significant difference between the average yearly age adjusted MR of the respective country and the average yearly age adjusted MR of Greece.

Rankings are by average yearly age adjusted MR without injuries of undetermined intent.

EU, European Union; IUI, injury of undetermined intent; MR, mortality rate.

Table 3 Percent potential reduction of intentional injury mortality in adults aged 15–64 years per 100 000 population by cause*, excluding and including injuries of undetermined intent, and annual number of lives saved in the EU countries based on the average of the last three available years (circa 2000).

| Country | Mortality rate by cause | Without injuries of undetermined intent | With injuries of undetermined intent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide | Homicide | IUI | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | |||

| Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | ||||||||

| Greece | 3.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 363 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 363 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Italy | 6.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 3175 | 8.0 | 38.0 | 1207 | 3550 | 9.0 | 44.6 | 1583 |

| Spain | 7.6 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 2402 | 8.8 | 43.2 | 1039 | 2480 | 9.1 | 45.0 | 1116 |

| Portugal | 7.1 | 1.7 | 7.2 | 613 | 8.8 | 43.3 | 265 | 1110 | 15.9 | 68.8 | 763 |

| UK | 8.8 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 3863 | 9.9 | 49.6 | 1914 | 5583 | 14.3 | 65.1 | 3636 |

| Netherlands | 11.1 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1369 | 12.6 | 60.3 | 826 | 1417 | 13.0 | 61.7 | 874 |

| Germany | 13.6 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 8250 | 14.5 | 65.5 | 5407 | 9557 | 16.8 | 70.3 | 6717 |

| Sweden | 14.7 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 929 | 16.0 | 68.9 | 640 | 1171 | 20.2 | 75.3 | 883 |

| Denmark | 15.4 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 607 | 16.8 | 70.3 | 427 | 787 | 21.7 | 77.0 | 606 |

| Ireland | 16.5 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 454 | 17.8 | 72.0 | 327 | 505 | 19.8 | 74.9 | 378 |

| Czech Republic | 16.9 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 1328 | 18.5 | 73.1 | 971 | 1556 | 21.7 | 77.1 | 1199 |

| Slovakia | 16.1 | 2.8 | 4.3 | 683 | 18.9 | 73.6 | 503 | 839 | 23.2 | 78.5 | 659 |

| Austria | 19.2 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1110 | 20.1 | 75.2 | 834 | 1173 | 21.2 | 76.5 | 898 |

| France | 19.4 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 7801 | 20.3 | 75.4 | 5885 | 8844 | 23.0 | 78.3 | 6927 |

| Poland | 19.3 | 2.3 | 6.9 | 5650 | 21.6 | 77.0 | 4348 | 7423 | 28.5 | 82.5 | 6125 |

| Belgium | 23.6 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 1739 | 25.7 | 80.7 | 1402 | 1932 | 28.6 | 82.6 | 1596 |

| Finland | 28.0 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 1107 | 31.5 | 84.2 | 932 | 1195 | 33.9 | 85.3 | 1019 |

| Slovenia | 30.5 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 443 | 31.8 | 84.3 | 373 | 486 | 35.0 | 85.8 | 417 |

| Hungary | 31.5 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 2382 | 34.2 | 85.4 | 2036 | 2496 | 35.9 | 86.1 | 2149 |

| Estonia | 33.9 | 17.6 | 9.9 | 466 | 51.5 | 90.3 | 421 | 557 | 61.4 | 91.9 | 512 |

| Latvia | 36.8 | 15.3 | 12.7 | 821 | 52.1 | 90.4 | 743 | 1020 | 64.8 | 92.3 | 941 |

| Lithuania | 59.0 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 1603 | 70.8 | 93.0 | 1490 | 1861 | 82.2 | 93.9 | 1748 |

| EU | 14.0 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 47156 | 15.5 | 67.9 | 32040 | 55904 | 18.4 | 73.0 | 40791 |

*Deaths due legal intervention or war operations are excluded.

†Bold numbers indicate a statistically significant difference between the average yearly age adjusted MR of the respective country and the average yearly age adjusted MR of Greece.

Rankings are by average yearly age adjusted MR without injuries of undetermined intent.

EU, European Union; IUI, injury of undetermined intent; MR, mortality rate.

Table 4 Percent potential reduction of intentional injury mortality in elderly people (aged 65+ years) per 100 000 population by cause*, excluding and including injuries of undetermined intent, and annual number of lives saved in the EU countries based on the average of the last three available years (circa 2000).

| Country | Mortality rate by cause | Without injuries of undetermined intent | With injuries of undetermined intent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide | Homicide | IUI | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | |||

| Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | ||||||||

| Greece | 5.2 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 122 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0 | 122 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0 |

| UK | 6.2 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 642 | 6.7 | 0.4 | 3 | 950 | 9.9 | 32.7 | 311 |

| Ireland | 8.6 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 37 | 8.9 | 25.2 | 9 | 42 | 10.1 | 34.1 | 14 |

| Italy | 13.2 | 0.7 | 4.2 | 1503 | 13.9 | 52.1 | 782 | 1988 | 18.2 | 63.2 | 1257 |

| Netherlands | 13.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 313 | 14.3 | 53.3 | 167 | 324 | 14.8 | 55.0 | 178 |

| Spain | 17.1 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1242 | 17.8 | 62.6 | 777 | 1277 | 18.3 | 63.6 | 812 |

| Poland | 16.3 | 2.0 | 12.0 | 871 | 18.4 | 63.6 | 554 | 1430 | 30.4 | 78.0 | 1116 |

| Portugal | 19.7 | 1.0 | 20.5 | 352 | 20.7 | 67.7 | 238 | 700 | 41.1 | 83.8 | 586 |

| Sweden | 20.6 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 341 | 21.6 | 69.1 | 236 | 400 | 25.5 | 73.8 | 295 |

| Slovakia | 19.6 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 135 | 22.1 | 69.8 | 94 | 166 | 27.3 | 75.5 | 126 |

| Finland | 21.5 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 178 | 22.9 | 70.9 | 126 | 193 | 24.9 | 73.2 | 141 |

| Denmark | 23.1 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 195 | 23.6 | 71.7 | 140 | 216 | 26.3 | 74.6 | 161 |

| Germany | 23.6 | 0.6 | 7.1 | 3406 | 24.2 | 72.4 | 2467 | 4511 | 31.3 | 78.7 | 3549 |

| Czech Republic | 26.7 | 1.2 | 6.5 | 400 | 27.9 | 76.1 | 304 | 493 | 34.4 | 80.6 | 397 |

| Belgium | 29.9 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 528 | 31.4 | 78.7 | 416 | 570 | 33.9 | 80.3 | 457 |

| France | 31.2 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 3121 | 31.8 | 79.0 | 2465 | 3494 | 35.5 | 81.2 | 2838 |

| Austria | 36.8 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 493 | 37.9 | 82.4 | 406 | 502 | 38.5 | 82.7 | 415 |

| Estonia | 35.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 92 | 44.0 | 84.8 | 78 | 104 | 50.0 | 86.6 | 90 |

| Latvia | 36.6 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 169 | 47.1 | 85.8 | 145 | 204 | 57.0 | 88.3 | 180 |

| Slovenia | 50.4 | 1.0 | 17.0 | 147 | 51.4 | 87.0 | 128 | 194 | 68.4 | 90.2 | 175 |

| Hungary | 53.1 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 871 | 55.8 | 88.0 | 767 | 916 | 58.7 | 88.6 | 812 |

| Lithuania | 47.3 | 8.7 | 10.1 | 275 | 56.0 | 88.1 | 242 | 325 | 66.1 | 89.9 | 292 |

| EU | 20.1 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 15433 | 21.1 | 68.3 | 10546 | 19121 | 25.9 | 74.3 | 14199 |

*Deaths due legal intervention or war operations are excluded.

†Bold numbers indicate a statistically significant difference between the average yearly age adjusted MR of the respective country and the average yearly age adjusted MR of Greece.

Rankings are by average yearly age adjusted MR without injuries of undetermined intent.

EU, European Union; IUI, injury of undetermined intent; MR, mortality rate.

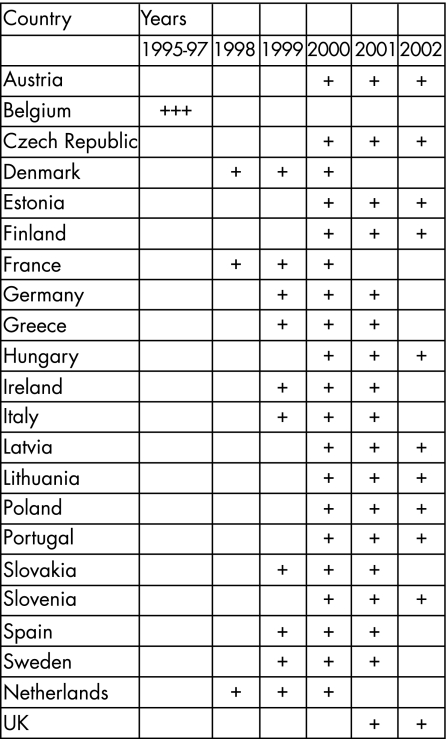

For the main analysis, data from the last three consecutive available years were obtained for each country (except the UK, where, Scotland, Wales, and England began using ICD10 at different times; consequently only two consecutive years were available at the time of analysis). The availability of data by country at the time of analysis is shown in fig 1. In addition, we carried out a regression analysis on intentional injury mortality rates over an approximately 10 year period in an attempt to discern longer term time trends.

Figure 1 Availability of injury mortality data in the WHO database by country and year.

Yearly averages of age adjusted mortality rates (based on the European standard population provided by WHO) were calculated to estimate—overall and within age groups—the potential number of lives saved in the EU if all member states achieved the same rate as the country with the lowest rate. The results were obtained from the formula:

LS = N*(PPR/100)

where LS = yearly average number of lives saved, N = average number of yearly deaths, and PPR = percent of potential reduction, based on the lowest yearly average mortality rate for the “best performing country” as derived from the formula:

PPR = 100*(AMRx−AMRs)/AMRx

where AMRx = average yearly age adjusted mortality rate of country X and AMRs = average yearly age adjusted mortality rate of the best performing country S.

Whether or not the “injury of undetermined intent” category includes intentional injury is a matter for debate.4 We therefore carried out two calculations, including and excluding injuries of undetermined intent.

Results

Our calculations suggest that more than 55 000 deaths of about 63 000 reported each year from suicide, homicide, and injuries of undetermined intent might have been avoided in the EU if all countries had achieved the intentional injury mortality reported by the member state with the lowest rate, namely Greece (4.1 per 100 000) (table 1). Two other Mediterranean countries, Italy and Spain, reported very low total intentional injury mortality rates. The rates of the three Baltic countries reached an average of over 10 times higher than that of Greece.

Table 1 Percent potential reduction in overall intentional injury mortality per 100 000 population by cause*, excluding and including injuries of undetermined intent, and annual number of lives saved in the EU countries based on the average of the last three available years (circa 2000).

| Country | Mortality rate by cause | Without injuries of undetermined intent | With injuries of undetermined intent | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide | Homicide | IUI | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | Deaths/year | Average yearly age adjusted MR | Lowest total rate | |||

| Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | Potential reduction (%)† | Lives saved | ||||||||

| Greece | 3.1 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 489 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 0 | 489 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Italy | 6.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 4703 | 7.0 | 41.0 | 1928 | 5569 | 8.1 | 49.1 | 2737 |

| UK | 6.6 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 4551 | 7.4 | 44.7 | 2033 | 6620 | 10.8 | 62.0 | 4105 |

| Spain | 7.0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 3660 | 7.9 | 47.8 | 1751 | 3774 | 8.1 | 49.4 | 1865 |

| Portugal | 7.0 | 1.3 | 7.5 | 970 | 8.2 | 50.0 | 485 | 1852 | 15.8 | 73.9 | 1369 |

| Netherlands | 9.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1701 | 10.1 | 59.3 | 1009 | 1762 | 10.5 | 60.7 | 1070 |

| Germany | 11.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 11763 | 12.5 | 67.1 | 7897 | 14209 | 14.9 | 72.4 | 10286 |

| Ireland | 12.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 497 | 13.0 | 68.4 | 340 | 554 | 14.6 | 71.7 | 397 |

| Sweden | 12.2 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 1278 | 13.2 | 68.9 | 880 | 1581 | 16.5 | 75.0 | 1186 |

| Denmark | 12.9 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 810 | 14.0 | 70.6 | 572 | 1010 | 17.6 | 76.6 | 773 |

| Slovakia | 13.0 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 826 | 15.2 | 72.9 | 602 | 1020 | 18.8 | 78.1 | 797 |

| Czech Republic | 14.3 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 1743 | 15.7 | 73.7 | 1285 | 2073 | 18.7 | 77.9 | 1615 |

| Poland | 14.9 | 1.8 | 6.0 | 6588 | 16.7 | 75.3 | 4964 | 8958 | 22.7 | 81.9 | 7335 |

| France | 16.5 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 11003 | 17.2 | 76.1 | 8373 | 12476 | 19.6 | 79.0 | 9851 |

| Austria | 17.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1617 | 17.9 | 76.9 | 1244 | 1689 | 18.7 | 78.0 | 1317 |

| Belgium | 19.2 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2287 | 21.0 | 80.3 | 1838 | 2526 | 23.2 | 82.2 | 2078 |

| Finland | 21.2 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1297 | 23.9 | 82.7 | 1073 | 1400 | 25.7 | 84.0 | 1175 |

| Slovenia | 26.1 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 592 | 27.1 | 84.8 | 502 | 683 | 31.1 | 86.8 | 593 |

| Hungary | 27.0 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 3279 | 29.4 | 86.0 | 2820 | 3441 | 30.8 | 86.6 | 2982 |

| Estonia | 26.8 | 13.0 | 7.4 | 569 | 39.8 | 89.6 | 510 | 678 | 47.2 | 91.3 | 619 |

| Latvia | 28.9 | 11.9 | 9.9 | 1000 | 40.7 | 89.9 | 899 | 1239 | 50.6 | 91.9 | 1138 |

| Lithuania | 44.9 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 1892 | 54.0 | 92.4 | 1747 | 2205 | 63.0 | 93.5 | 2061 |

| EU | 11.6 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 63113 | 12.9 | 68.0 | 42923 | 75807 | 15.4 | 73.3 | 55555 |

*Deaths due legal intervention or war operations are excluded.

†Bold numbers indicate a statistically significant difference between the average yearly age adjusted MR of the respective country and the average yearly age adjusted MR of Greece.

Rankings are by average yearly age adjusted MR without injuries of undetermined intent.

EU, European Union; IUI, injury of undetermined intent; MR, mortality rate.

Children (0–14 years)

These results are shown in table 2 (see http://www.injuryprevention.com/supplemental). Over 67% of homicide and suicide deaths in children (n = 348) might have been avoided each year in the EU if all countries had matched the rate reported by Greece (0.2 per 100 000). A further 11% might have been avoided if injuries of undetermined intent are included. This amounts to nearly four fifths (78%) of all intentional injury deaths in children, or 601 lives. The potential savings range from 20% to 95% across countries. The Baltic states had a high rate in all causation categories, whereas Portugal and Slovakia had a notably higher rate of injuries of undetermined intent compared to suicide and homicide. The average intentional mortality rate for children was higher for homicides than suicides or injuries of undetermined intent (0.4, 0.2, and 0.3 per 100 000, respectively).

Adults (15–64 years)

These results are shown in table 3 (see http://www.injuryprevention.com/supplemental). Almost 68% (n = 32 000) of adult deaths from homicide and suicide might have been avoided each year if all countries had achieved the same rate as Greece, the country with the lowest rate (5.0 per 100 000). About 40 000 deaths (73%) from intentional injury in the EU might have been avoided when injuries of undetermined intent are included. Most of the potentially avoided deaths would be from suicides as they are on average nearly 10 times more frequent than homicides in adults (14.0 and 1.5 per 100 000, respectively). The potential savings across member states range from 45% to 94%. Lithuania had a substantially higher rate of suicides than any other country (59 per 100 000), whereas Estonia and Latvia had more homicides than other countries (17.6 and 15.3 per 100 000, respectively). Injuries of undetermined intent comprised a relatively high proportion of intentional injury deaths in Portugal, the UK, and Poland compared with the other countries.

Elderly (65 and over)

These results are shown in table 4 (see http://www.injuryprevention.com/supplemental). Over 68% of elderly deaths (n = 10 600) from homicide and suicide in EU might have been avoided each year if all countries had achieved the same rate as Greece (6.7 per 100 000). A further 4000 lives might be saved if injuries of undetermined intent are included in the calculation. In the elderly, suicides are on average over 20 times more frequent than homicides and four times more frequent than deaths from injuries of undetermined intent (20.1, 1.0, and 4.9 per 100 000, respectively). Hungary, Slovenia, and Lithuania had the highest rates of suicides (53.1, 50.4, and 47.3 per 100 000, respectively), whereas Portugal and Slovenia reported high death rates of injuries of undetermined intent (20.5 and 17.0 per 100 000, respectively). Ireland had the lowest and Latvia the highest rate of homicide in this age group (0.3 and 10.5 per 100 000, respectively).

Finally, the stability of these intercountry variations over approximately 10 years is shown in table 5. Although several countries experienced significant declines in intentional injury mortality between the earlier and later periods, the ranking according to rates remains virtually unchanged.

Table 5 Age adjusted mortality from intentional injuries* (per 100 000 person years) and regression derived annual change in the EU member states, ∼1991 to ∼2000.

| Country | Average yearly age adjusted MR of the first 3 available years (c 1991) | Average yearly age adjusted MR of the last 3 available years (c 2000) | Annual change (%) | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 4.5 | 4.1 | −1.21 | −2.80 to 0.40 | 0.18 |

| Italy | 8.8 | 7.0 | −3.22 | −3.77 to −2.67 | 0.0001 |

| UK | 8.3 | 7.4 | −1.31 | −2.10 to −0.52 | 0.01 |

| Spain | 8.0 | 7.9 | 0.02 | −0.89 to 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Portugal | 8.9 | 8.2 | −1.12 | −6.32 to 4.36 | 0.69 |

| Netherlands | 11.1 | 10.1 | −1.19 | −1.58 to −0.79 | 0.0004 |

| Germany | 15.3 | 12.5 | −2.81 | −3.22 to −2.40 | 0.0001 |

| Ireland | 11.5 | 13.0 | 2.15 | 0.62 to 3.70 | 0.02 |

| Sweden | 15.6 | 13.2 | −2.37 | −2.93 to −1.80 | 0.0001 |

| Denmark | 17.5 | 14.0 | −5.15 | −6.20 to −4.10 | 0.0002 |

| Slovakia | 17.0 | 15.2 | −1.82 | −2.86 to −0.77 | 0.01 |

| Czech Republic | 19.2 | 15.7 | −2.82 | −3.83 to −1.80 | 0.0007 |

| Poland | 17.9 | 16.7 | −0.90 | −1.14 to −0.65 | 0.0004 |

| France | 20.3 | 17.2 | −2.22 | −3.01 to −1.43 | 0.0006 |

| Austria | 21.2 | 17.9 | −2.42 | −3.18 to −1.64 | 0.0003 |

| Belgium | 19.6 | 21.0 | 1.10 | −0.06 to 2.27 | 0.10 |

| Finland | 29.5 | 23.9 | −2.91 | −3.53 to −2.28 | 0.0001 |

| Slovenia | 31.0 | 27.1 | −2.02 | −2.69 to −1.34 | 0.0004 |

| Hungary | 36.2 | 29.4 | −2.94 | −3.60 to −2.26 | 0.0001 |

| Estonia | 66.2 | 39.8 | −6.66 | −7.95 to −5.36 | 0.0001 |

| Latvia | 62.9 | 40.7 | −6.06 | −6.76 to −5.36 | 0.0001 |

| Lithuania | 59.7 | 54.0 | −1.56 | −2.44 to −0.68 | 0.009 |

| EU | 15.1 | 12.9 | −1.84 | −3.27 to −0.40 | 0.03 |

*Suicides and homicides, but excluding injuries of undetermined intent.

CI, confidence interval; MR, mortality rate.

Discussion

At the beginning of the new millennium, the potential scope for reduction of intentional injury deaths in the EU appears greatest for suicide as the rates are about 20 times those of homicide and five times those of injuries of undetermined intent. The elderly have the highest rates of suicide in most countries, while Finland, Ireland, Lithuania, Poland, and the UK appear to have a larger problem with adult (15–64 years) rather than elderly suicide, a peculiarity further magnified if injuries of undetermined intent are included with suicides. Adults (15–64 years) have the highest rates of homicide in most countries.

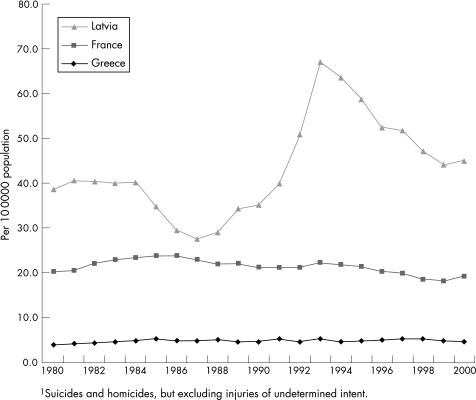

There is an intriguing geographical pattern of intentional injury mortality (largely due to suicide) in the EU: countries around the Mediterranean (Greece, Italy, and Spain) report low rates (fewer than 10 per 100 000 when injuries of undetermined origin are included); the Netherlands, UK, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Sweden, Denmark, Czech Republic, Austria, Slovakia, France, Poland, Belgium, and Finland report intermediate rates (10–30 per 100 000); while Slovenia, Hungary, and the Baltic States report the highest rates (more than 30 per 100 000). Indeed Hungary and the Baltic states are among the countries that have the highest rates of suicides in the world,6 the reasons for which are obscure. These countries have had a turbulent history before, during, and since the break up of the Soviet Union. Alcohol consumption,15 together with social disorganization and the psychological stresses associated with rapid social, economic, and political changes, are thought to be contributing factors.5 In the Baltic states, for example, the trend in suicides was downwards (by over 20%) in the late 1980s followed by a sharp increase (approximately 60–70%) in the early 1990s (fig 2), during the dismantling of corporate socialism.5

Figure 2 Intentional injury mortality rates in three EU countries 1980–2000 (source: WHO‐Europe injury database). Injuries of undetermined intent excluded.

The specific reasons for the very low intentional injury mortality rate of Greece are a matter for conjecture. A necropsy is required by law in the case of every violent death in Greece and the country's necropsy rate for hospital deaths (around 45%) is not especially low in EU terms.16 Our findings accord with those of crime surveys that indicate a relatively low level of homicide in Greece compared with other EU member states including the UK.17 Greece also appears to have lower risk factor levels for violence than many other EU countries. Alcohol consumption, for example, is below the EU average and only Italy, Norway, and Sweden had lower alcohol consumption rates in 2003, and binge drinking appears less common in Mediterranean regions.16

Low rates of suicide in Mediterranean regions have been attributed to climate. Sunshine appears to have a beneficial impact on mood, and annual total sunshine has been shown to correlate negatively with suicide rates within countries even after adjusting for confounding variables such as sociodemographic factors. Paradoxically, although sunshine appears to exert a long term protective effect on suicide risk, intense short term exposure may act as a trigger for suicide.9 Other factors influencing intentional injury mortality rates are the prevalence of psychiatric diseases and especially that of mood disorders and substance abuse, socioeconomic and cultural differences, the quality of medical care, educational level, legislation (for example, relating to gun ownership18), and media reporting19. In England and Wales there was an increase in suicides following Princess Diana's funeral in 199720 and a decrease following the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001.21

Although national and regional cultural and religious characteristics may influence intentional injury risk, we acknowledge that these factors may also produce methodological artifacts. Any investigation of international variation in injury rates is bedeviled by varying recording, coding and classification practices. The diagnosis and recording of intentional injury is particularly problematic as intent can often be difficult to assess. The WHO highlights two important points: first, the use of force does not necessarily correlate with intention to damage; second, there may be differences in intent to injure and intent to use violence—forms of which may be culturally acceptable in some settings.8 There are also difficulties in assessing the accuracy of causation classification. Resistance to the recording of suicide may contribute to the low reported suicide rates of some Mediterranean countries though, in common with a previously reported study,4 we could identify no empirical evidence to suggest that this is a major explanatory factor.

Procedures for recording a death as suicide are not uniform. Some countries require a suicide note to register a death as suicide while others require that a coroner undertakes an assessment of intent. Assessment of intent appears to be related to the chosen suicide method, and underreporting may be as high as 40%.22 In situations where suicide is socially or culturally unacceptable, the death may be recorded and classified as undetermined or even unintentional, depending on the method used—for example, a suicide disguised in a motor vehicle crash23 (covert suicide). Some hospital admissions for unintentional injury, including motor vehicle crashes, may be unrecognized suicide attempts.24 In Portugal the rate of undetermined deaths tends to surpass that of suicides, prompting concern about possible misclassification of cause of death. Homicides are also liable to misclassification as undetermined or unintentional injury. Some cases of infant homicide (infanticide) may be misclassified as SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome).25 Some elderly deaths classified as natural, accidental, and undetermined causes may be the result of neglect or abuse.8

On the other hand, all the mortality data are derived from real death certificates, the coding of which is subject to strict WHO quality control procedures.26 Moreover, the differences between high rate and low rate countries are not confined to a narrow time window but persist over approximately a decade. To explore and illustrate the longer term time trends, we carried out an additional analysis of the period 1980 to 2000 for three countries—Greece, France, and Latvia—that experienced low, middle, and high intentional injury rates, respectively (fig 2). Their relative positions are remarkably stable over time with the exception of the temporary surge in rates in Latvia during the period of political upheaval to which we have referred above. In other words, the intercountry differences we have observed are so large and consistent that underrecording or other methodological artifact is, in our view, unlikely to explain the magnitude of the variation.

Whether the potential reductions in fatal intentional injuries presented here represent more than a theoretical opportunity is a matter for speculation, as we do not fully understand the reasons underlying the varying mortality rates. For the purpose of this exercise, we hypothesized that all countries, through the implementation of effective prevention strategies, could achieve the lowest reported national intentional injury rate. Such an assumption may be too optimistic as intentional injury reduction is notoriously difficult to achieve and it is debatable whether a low mortality rate is an indication of “best practice”. Furthermore, preventive measures that work well in one country might not easily be transferred to another. Conversely, there is little evidence that the country with the lowest rate has achieved the absolute limit in intentional injury reduction, which in turn raises the possibility that we may have underestimated the potential number of lives saved. The relative importance of these two possible sources of error operating in opposite directions is difficult to assess.

An international consensus is growing that the prevention of intentional injury is possible though, in common with other branches of public health, the extent to which research based knowledge is applied varies widely from country to country. Successful suicide prevention strategies include limiting the availability of lethal methods, such as reducing the access to barbiturates,27 to lethal pesticides such as paraquat,28 domestic gas detoxification,29 the introduction of catalytic converters on cars,30 the reduction of the pack size and introduction of blister packs of analgesics31,32 and regulation of handguns (a measure that also helps prevent homicides).33 Some researchers have suggested that restricting firearms will result in suicide methods being substituted with, for example, leaping.34 Other interventions include screening for suicide risk in primary care setting through targeting high risk groups such as young men, patients newly discharged from psychiatric care, and people with a history of parasuicide or deliberate self harm. The role of the effective treatment of depression as a suicide prevention measure should not be overlooked.35

Key points

Globally, more than one in four injury deaths are caused by intentional injury.

About 63 000 people die annually in the European Union from intentional injury, but there is wide variation in mortality from intentional injury across the EU countries.

Over 73% (∼55 000 per annum) of all intentional injury deaths could have been avoided if all EU countries had matched the country with the lowest rate.

How this theoretical observation might be translated into practice requires further exploration.

Interpersonal violence prevention is even more challenging. Measures that seem to be effective include early life interventions (prenatal to age 6) to avoid youth violence36,37 and home visitation in pregnancy and infancy to reduce the likelihood of child neglect and abuse.38 Legislation outlawing corporal punishment may protect children at risk of abuse,39 and promoting sex equality has a role in preventing violence against women.37

In conclusion, our epidemiological analyses have shown that there may be substantial scope for the avoidance of intentional injury deaths in the EU, were all member states to reduce their intentional injury mortality rates to those of the country reporting the lowest rate. How this hypothetical potential saving of lives might be translated into practice requires further exploration.

Implications for prevention

There is a clear requirement for a more intensive research effort into the development, implementation, and evaluation of preventive interventions in the field of intentional injury. Nevertheless, we suggest that the wide international variation in mortality from these causes reflects, in part at least, varying commitment to and implementation of preventive interventions of known efficacy. Above all, this study points to the urgent need for public health policy makers in Europe to redouble their efforts to increase the effectiveness of current suicide and violence prevention strategies throughout the continent.

Tables 2–4 are available on our website

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the reviewers of an earlier draft for their constructive suggestions. This study was partly supported by the Athens University Medical School and partly by EU grants for the Coordination and Administration of the European Injury Prevention Working Party (DG SANCO, 2003313) and the European Network for Safety among Elderly‐EUNESE (2003316) programs.

Footnotes

Tables 2–4 are available on our website

References

- 1. In: Peden M, McGee K, Krug E. eds. Injury: a leading cause of the global burden of disease, 2000. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2002

- 2.Peden M, McGee K, Sharma G.The injury chart book: a graphical overview of the global burden of injuries. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2002

- 3.Morrison A, Stone D H, Working Group Injury mortality in the European Union 1984–1993. An overview. Eur J Public Health 200010201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chishti P, Stone D H, Corcoran P.et al Suicide mortality in the European Union. Eur J Public Health 200313108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makinen I H. Eastern European transition and suicide mortality. Soc Sci Med 2000511405–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levi F, La Vecchia C, Lucchini F.et al Trends in mortality from suicide, 1965–99. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003108341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertolote J M, Fleischmann A. A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. Suicidologi 200276–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8. In: Krug E G, Dahlberg L L, Mercy J A.et al eds. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2002

- 9.Papadopoulos F C, Frangakis C E, Skalkidou A.et al Exploring lag and duration effect of sunshine in triggering suicide. J Affect Disord 200588287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO The world health report 2001 – mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2001

- 11.Weyerer S, Wiedenmann A. Economic factors and the rates of suicide in Germany between 1881 and 1989. Psychol Rep 1995761331–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kury H, Obergfell‐Fuchs J, Woessner G. The extent of family violence in Europe: a comparison of national surveys. Violence Against Women 200410749–769. [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Leo D. Cultural issues in suicide and old age. Crisis 19992053–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Leo D, Hickey P A, Neulinger K.et alAgeing and suicide. Sydney: Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2002

- 15.Wasserman D, Varnik A, Eklund G. Male suicides and alcohol consumption in the former USSR. Acta Psychiatr Scand 199489306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Health for all Database (HFA‐DB) World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe. http://data.euro.who.int/hfadb/ 2006

- 17.Barclay G, Tavares S. International comparisons of criminal justice statistics. Research Development & Statistics Directorate, UK Home Office, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/international1.html 2002

- 18.Philippakis A, Hemenway D, Alexe D M.et al A quantification of preventable unintentional childhood injury mortality in the United States. Inj Prev 20041079–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bollen K A, Phillips D P. Imitative suicides: a national study of the effects of television news stories. Am Sociol Rev 198247802–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawton K, Harriss L, Appleby L.et al Effect of death of Diana, Princess of Wales on suicide and deliberate self‐harm. Br J Psychiatry 2000177463–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salib E. Effect of 11 September 2001 on suicide and homicide in England and Wales. Br J Psychiatry 2003183207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper P N, Milroy C M. The coroner's system and under‐reporting of suicide. Med Sci Law 199535319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bollen K A, Phillips D P. Suicidal motor vehicle fatalities in Detroit: a replication. Am J Sociol 198187404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grossman D C, Soderberg R, Rivara F P. Prior injury and motor vehicle crash as risk factors for youth suicide. Epidemiology 19934115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levene S, Bacon C J. Sudden unexpected death and covert homicide in infancy. Arch Dis Child 200489443–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO More information on the mortality database. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2005 (WHO Statistical Information System, WHO mortality database: http://www3.who.int/whosis/mort/text/description.cfm?path = whosis,inds,mort,mort_info&language = english )

- 27.Oliver R G, Hetzel B S. Rise and fall of suicide rates in Australia: relation to sedative availability. Med J Aust 19722919–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowles J R. Suicide in Western Samoa: an example of a suicide prevention program in a developing country. In: Diekstra RF, Gulbinat RW, De Leo D, et al eds. Preventive strategies on suicide. Leiden: Brill, 1995173–206.

- 29.Kreitman N. The coal gas story. United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960–71. Br J Prev Soc Med 19763086–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amos T, Appleby L, Kiernan K. Changes in rates of suicide by car exhaust asphyxiation in England and Wales. Psychol Med 200531935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J.et al UK legislation on analgesic packs: before and after study of long term effect on poisonings. BMJ 20043291076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turvill J L, Burroughs A K, Moore K P. Change in occurrence of paracetamol overdose in UK after introduction of blister packs. Lancet 20003552048–2049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loftin C, McDowall D, Wiersema B.et al Effects of restrictive licensing of handguns on homicide and suicide in the District of Columbia. N Engl J Med 19913251615–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rich C L, Young J G, Fowler R C.et al Guns and suicide: possible effects of some specific legislation. Am J Psychiatry 1990147342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mann J J, Apter A, Bertolote J.et al Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 20052942064–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kellermann A L, Fuqua‐Whitley D S, Rivara F P.et al Preventing youth violence: what works? Annu Rev Public Health 199819271–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butchart A, Phinney A, Check P.et al Preventing violence. A guide to implementing the recommendations of the World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2004

- 38.Olds D L, Eckenrode J, Henderson C R.et al Long‐term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen‐year follow‐up of a randomized trial. JAMA 1997278637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durrant J E. Evaluating the success of Sweden's corporal punishment ban. Child Abuse Negl 199923435–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]