Abstract

The aim of the study was to create a profile of Jamaican homicide victims and to describe the circumstances, motives, and the weapons used in homicide incidents. The authors read the police narratives for all Jamaican homicides 1998–2002 and coded them using a predetermined set of variables. Analyses were conducted to describe victim characteristics, motive, and weapon use. The majority of homicide victims were male (over 89%), and 15–44 years old (80%). The rate of homicide for males age 15–44 years was 121 per 100 000 compared with a rate of 12 per 100 000 for females in the same age group. The main motives for homicide were disputes (29%) and reprisals (30%). Gunshot wounds were the cause of death in 66% of all homicides. Guns were used primarily in reprisals, robbery, and drug/gang related homicides; in half of all dispute related homicides the perpetrator used a knife. Homicides in Jamaica are not primarily gang or robbery related. Rather, they are mainly caused by arguments or reprisals. Homicide has become a common feature of dispute resolution in Jamaica.

Keywords: violence, homicide, guns, Jamaica

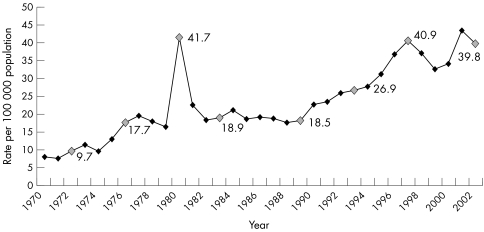

Jamaica has a high and rising rate of homicide. In 1970, the homicide rate was 8.1 per 100 000; by 2002, it had risen to 40 per 100 000 people (fig 1). Jamaica now has the world's third highest homicide rate behind South Africa and Colombia.1 Historically, violence in Jamaica was dominated by rivalry between two political parties which armed young men in their fight for power.2 Many attribute the current homicide rate to urban poverty, the drug trade, and the illegal importation of firearms.3,4,5 A high level of lethal violence reduces tourism, creates economic hardship, and strains an already burdened health system.6,7

Figure 1 Reported murder rate and election years, 1970–2002.

The goal of the study is to create a profile of the victims of homicide, the recorded motives, and the weapons used. It responds to the 49th Annual World Health Assembly's call to characterize the problem of violence and to promote steps for violence prevention.8

Methods

Detailed information from 1998–2002 (n = 4873 cases) was obtained from the Jamaican police (data on homicides before 1998 are incomplete). Disaggregated police records are not in the public domain, but were made available to the authors. Police data provided the age and sex of the victims, the motive, and the weapon used. Each homicide also has a brief case narrative, which was read in detail. From the narratives, data on the characteristics of homicides were extracted using a standardized data collection instrument.

Four variables were investigated: victim demographics—that is, age and sex; implement used (gun; knife; machete or ice pick; and other, such as blunt instruments, acid, or rope); and motive for the homicide (dispute; reprisal; robbery; drugs/gang; rape; other, such as mob killing, political, and unknown). Disputes were classified if the victim and perpetrator were involved in a quarrel/fight at the time of the homicide. Reprisals are revenge killings; underlying causes could be previous robberies, dispute, or drug and gang related activity.

Frequencies were calculated and the data were cross tabulated. Pearson's χ2 test was used to determine levels of statistical significance.

Results

During the five year study period (1998–2002) the Jamaican police reported 4873 homicides. Most of the homicides (76%) occurred in Kingston, the capital city, and surrounding areas. The majority of homicide victims were male (89%) and were between 15 and 44 years of age (80%) (table 1). The mean age of the victims was 32 years with a minimum age of newborn and a maximum age of 90 years. Fewer than 2% of all homicide victims were under the age of 15; among these children, boys and girls had almost equal chances of being victims. At the age of 15, homicide victimization increased rapidly. For 15–44 year olds, the rate of homicide for males was 121 per 100 000—almost 10 times the rate for females. The homicide rate decreased considerably for males aged 45 years and older (61 per 100 000 for males 45–59; 28 per 100 000 for males aged 60+).

Table 1 Percent and rate of homicide by victim sex and age, 1998–2002.

| Age group | Count | Rate, male* | Rate, female† | Male (%) | Female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 34 | 2 | 3 | 47 | 53 |

| 5–14 | 58 | 2 | 2 | 55 | 45 |

| 15–29 | 2233 | 121 | 13 | 90 | 10 |

| 30–44 | 1688 | 121 | 11 | 91 | 9 |

| 45–59 | 483 | 61 | 7 | 90 | 10 |

| ⩾60 | 222 | 28 | 7 | 76 | 24 |

| Unknown | 155 | –‡ | –‡ | 96 | 4 |

| All ages | 4873 | 68 | 8 | 89 | 11 |

*Rate per 100 000 male population.

†Rate per 100 000 female population.

‡Not calculated.

The two main motives of homicide were disputes (29%) and reprisals (30%) (table 2). Drug or gang related activities were the third motive of homicide accounting for 20%, followed by robbery (14%). Disputes were the most common motive for female homicide (43%). Drugs/gangs and robberies accounted for only 20% of all female murders. Thirty females were raped and killed between 1998 and 2002.

Table 2 Motive for homicide by victim sex and age, 1998–2002.

| Count | Dispute (%) | Reprisal (%) | Robbery (%) | Drugs/gang (%) | Rape (%) | Other (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victim sex* | ||||||||

| Male | 4350 | 27 | 31 | 14 | 22 | 0 | 6 | 100 |

| Female | 522 | 43 | 27 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 100 |

| Victim age (years) | ||||||||

| 0–4 | 34 | 65 | 21 | –† | 9 | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| 5–14 | 58 | 43 | 21 | 3 | 17 | 14 | 2 | 100 |

| 15–29 | 2233 | 29 | 34 | 6 | 26 | –† | 5 | 100 |

| 30–44 | 1688 | 28 | 30 | 16 | 19 | –† | 6 | 100 |

| 45–59 | 483 | 28 | 23 | 34 | 11 | –† | 4 | 100 |

| ⩾60 | 222 | 31 | 17 | 41 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 100 |

| Total | 4873 | 29 | 30 | 14 | 20 | 1 | 6 | 100 |

*The sex of one victim is unknown.

†Less than 1%.

For children 0–14 years, the main motive for homicide was dispute, for people aged 15–44 the main motive was reprisal, and for people aged 45 and older the main motive was robbery. Drug and gang activity played a greater role as a motive for homicide of people aged 15–29 than in any other age group but still accounted for only 26% of their homicides. In no age group was the main motive drugs and/or gang activity.

The implements most commonly used in murders were guns (66%), followed by knives (19%), and machetes or ice‐picks (6%) (table 3). Guns were overwhelmingly used in gang and drug related homicides (94%), reprisals (86%), and robbery (76%). On the other hand, the knife was used in 48% of dispute related homicides, double the rate of gun use. Of 30 rape homicides, “other” implements were used in 60% whereas the gun was used in only 13%.

Table 3 Motive, victim sex, age, and weapon used in homicides, 1998–2002.

| Gun (%) | Knife (%) | Machete or Ice‐pick (%) | Other weapon (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motive | |||||

| Dispute | 22 | 48 | 14 | 16 | 100 |

| Reprisal | 86 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 100 |

| Robbery | 76 | 13 | 2 | 9 | 100 |

| Drugs/gang | 94 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 100 |

| Rape | 13 | 27 | 0 | 60 | 100 |

| Other | 60 | 13 | 9 | 18 | 100 |

| Victim sex | |||||

| Male | 68 | 19 | 5 | 8 | 100 |

| Female | 48 | 25 | 7 | 20 | 100 |

| Victim age (years) | |||||

| 0–4 | 27 | 6 | 8 | 59 | 100 |

| 5–14 | 41 | 24 | 8 | 27 | 100 |

| 15–29 | 70 | 19 | 5 | 6 | 100 |

| 30–44 | 68 | 19 | 6 | 7 | 100 |

| 45–59 | 56 | 21 | 9 | 14 | 100 |

| ⩾60 | 41 | 22 | 13 | 24 | 100 |

| Unknown | 63 | 19 | 3 | 15 | 100 |

| Total (%) | 66 | 19 | 6 | 9 | 100 |

Guns were the weapon most often used in all age groups, except for children 0–4 years old. Gun homicide as a percentage of all homicides was highest for victims 15–44 years of age, the age group which accounted for 80% of all homicide victims.

This study has various limitations. First, the data come exclusively from police reports. Currently in Jamaica, the police have the most comprehensive record of reported homicides in the country. The national registry is unable to classify the cause of death for the majority of victims of homicide. Second, fatal shootings by the police are not included in homicide reports and are therefore excluded from this database. These killings are not insubstantial.9 Third, the data deal only with deaths; non‐fatal violence is excluded. The health department has only recently developed a system for collecting data on victims of violence who present at hospital emergency rooms.10 Finally, motives are sometimes ambiguous; the first author therefore read every case narrative to clarify the reason for the homicide.

Discussion

Jamaica has had a rapidly rising homicide rate for over 30 years. Over time, Jamaica has developed a culture of violence. The police narratives illustrate how common it has become for someone to be murdered—even in minor disputes over a cooking pot, cigarettes, or a bingo game. In 2002, there were many more people killed in disputes than were killed in all homicides in 1970.

Reprisal killings perpetuate violence. Many of these are revenge murders for previous murders. A saying in Jamaica is “If you can't catch Harry, you catch his shirt”. In other words, if you cannot exact retribution against the right person, then hurt the nearest person related to him. This makes retribution easy, increasing the likelihood of continued killings. Reprisal killings accounted for far more deaths in 2002 than all homicides in 1970.

The violence problem in Jamaica is particularly acute in Kingston and other urban areas. A study of high school students in the country capital found that almost 80% had witnessed violence in their communities, and 45% in their homes.11 A study of 11–12 year olds in Jamaican urban areas found that a quarter had witnessed severe acts of physical violence, 8% had been stabbed, and over one third had had a family member or close friend murdered.12

The Jamaican society needs sustainable efforts to support the prevention of violence. This can be done by fostering non‐violent approaches to dispute resolution.13 A national peace education curriculum could be developed and pertinent methods borrowed from projects such as the Hague Appeal for Peace.14 As homicide victimization increases greatly after adolescence, teaching conflict resolution skills in the schools at an early age would be useful for breaking the cycle of violence.15 The justice system can also be strengthened and access to conflict mediation services improved.

Young males in urban areas are particularly at risk of homicide victimization. Increasing protective factors for boys is vital.16 Programs geared at young males could lead to more positive social behavior and lower the risk of involvement in violence.17

Jamaica also needs help in limiting gun trafficking. Two thirds of Jamaican homicides are gun homicides and firearm availability increases the risk of homicides.18 The Jamaican government needs to find non‐violent strategies for reducing access to illegal firearms.

Finally, timely and accurate data on violence are useful to inform policies and interventions.19 A comprehensive violence injury surveillance system that links data among health departments, vital records registries, and the police needs to be developed. Tools for this can be borrowed from the CDC/WHO Injury Surveillance guidelines or the National Violent Death Reporting System in the United States.20,21

Key points

In Jamaica, there is a higher risk for being killed because of a dispute or reprisal than robbery or drug/gang activity.

Males between 15–44 years are at high risk for being victims of homicide.

The gun is the main weapon used in homicides, but the knife is used in nearly half of all dispute related homicides.

Violence has become the norm for dispute resolution and Jamaica has developed a “culture of violence”.

Strategies for promoting a culture of peace are needed in Jamaica.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people for their help: Richard Weisskoff, PhD, Anthony Harriott, PhD, Maria Elena Villar, MPH, Deb Azreal, PhD, and Matthew Miller, MD, MPH. We would also like to thank the Statistics Department of the Jamaica Constabulary Force, Harvard Injury Control Research Center, Centers for Disease Control, and Prevention and the Yerby Postdoctoral Fellowship Program for their support.

Footnotes

Funding: this research was supported in part by Grant/Cooperative Agreement U49/CCR422425‐01 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The contents of the publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. The CDC had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: none.

Ethics approval: this research was deemed exempt from IRB approval by the Human Subjects Committee at the Harvard School of Public Health.

References

- 1.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Seventh United Nations survey of crime trends and operations of criminal justice systems, covering the period 1998–2000. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Centre for International Crime 2000

- 2.Figueroa M, Sives A. Homogenous voting, electoral manipulation and the ‘garrison' process in post‐independence Jamaica. J Commonw Comp Polit 20024081–108. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy H.They cry respect! Urban violence and poverty in Jamaica. Kingston: Centre for Population, Community and Social Change, Department of Sociology and Social Work, University of the West Indies, 2001

- 4.Sives A. Changing patrons, from politicians to drug don: Clientelism in downtown Kingston, Jamaica. Lat Am Perspect 20022966–89. [Google Scholar]

- 5. In: Harriott A. ed. Understanding crime in Jamaica: new challenges for public policy. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2003

- 6.Khan A. WHO argues the economic case for tackling violence. Lancet 20043632058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zohoori N, Ward E, Gordon G.et al Non‐fatal violence‐related injuries in Kingston, Jamaica: A preventable drain on resources. Inj Control Saf Promot 20029255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krug E G, Mercy J A, Dahlberg L L.et al World report on violence and health. Biomedica 200222(suppl 2)327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harriott A. Police and crime control in Jamaica: Problems of reforming ex‐colonial constabularies. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2000

- 10.Ward E, Arscott‐Mills S, Gordon G.et al The establishment of a Jamaican all‐injury surveillance system. Inj Control Saf Promot 20029219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soyibo K, Lee M G. Domestic and school violence among high school students in Jamaica. West Indian Med J 200049232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samms‐Vaughan M E, Jackson M A, Ashley D E. Urban Jamaican children's exposure to community violence. West Indian Med J 20055414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Milestones of a Global Campaign for Violence Prevention 2005: changing the face of violence prevention. Geneva: WHO Press, 2005

- 14.Hague Appeal for Peace in cooperation with the United Nations Department for Disarmament Affairs Hague appeal for peace disarmament education and changing mindsets to reduce violence and sustain the removal of small arms. New York: Town Crier Printing, 2005

- 15.Butchart A, Phinney A, Check P.et alPreventing violence: a guide to implementing the recommendations of the World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: Department of Injuries and Violence Prevention, World Health Organization, 2004

- 16.Blum R W, Ireland M. Reducing risk, increasing protective factors: findings from the Caribbean youth health survey. J Adolesc Health 200435493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper W O, Lutenbacher M, Faccia K. Components of effective youth violence prevention programs for 7‐ to 14‐year‐olds. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 20001541134–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hepburn L M, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and homicide: A review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav 20049417–440. [Google Scholar]

- 19.German R R.et al Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, MMWR, July 27, 2001/50(RR13):1–35. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5013a1.htm (accessed December 2005)

- 20. In: Holder Y, Peden M, Krug E, eds. Injury surveillance guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 200116–91.

- 21.Paulozzi L J, Mercy J, Frazier L., Jret al CDC's national violent death reporting system: Background and methodology. Inj Prev 20041047–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]