Abstract

Objective

To further establish the psychometric properties of the Parent Supervision Attributes Profile Questionnaire (PSAPQ), a questionnaire measure of parent supervision that is relevant to understanding risk of unintentional injury among children 2 through 5 years of age.

Methods

To assess test‐retest reliability, parents completed the PSAPQ twice, with a one month interval. Internal consistency estimates for the PSAPQ were also computed. Confirmatory factor analyses were applied to the data to assess the four factor structure of the instrument by assessing the convergent and divergent validity of the subscales and their respective items.

Results

Test‐retest reliability and internal consistency scores were good, exceeding 0.70 for all subscales. Factor analyses confirmed the hypothesized model—namely that the 29 item questionnaire comprised four unique factors: protectiveness, supervision beliefs, risk tolerance, and fate influences on child safety.

Conclusions

Previous tests comparing the PSAPQ with indices of actual supervision and children's injury history scores revealed good criterion validity. The present assessment of the PSAPQ revealed good reliability (test‐retest reliability, internal consistency) and established the convergent and divergent validity of the four factors. Thus, the PSAPQ has proven to have strong psychometric properties, making it a unique and useful measure for researchers interested in studying links between supervision and young children's risks of unintentional injury.

Keywords: child, unintentional injury, supervision, measurement, validity, reliability

Unintentional injury poses a serious threat to the health and safety of children. In industrialized nations, unintentional injury is the leading cause of death and hospitalization for children over 1 year of age.1,2 In the United States, for example, children are more likely to die of unintentional injury than of the next nine leading causes combined.3 For toddlers, the majority of these injuries occur in or around the home when their safety is the responsibility of a parent or other caregiver.4 There has been considerable speculation that inadequate supervision may be an important contributing factor for understanding childhood injuries.5,6,7,8,9 In fact, a recent study examining the characteristics of injury deaths among children aged 0–6 years of age in Alaska and Louisiana concluded that inadequate supervision was specifically the most common preventable factor that led to death, accounting for 43% of deaths.10 Evidence linking supervision directly to child injury risk, however, has proven difficult to obtain, largely because of the methodological challenges in measuring supervision.11,12

To date, the methods used to study supervision have included naturalistic observations,13,14 self reports about supervision,15,16,17 and participant event monitoring methods in which caregivers track ongoing supervision in diary records.18,19,20,21,22 These methods have provided the first direct evidence that inadequate supervision is associated with increased risk of injuries to young children. However, these methods are extremely time consuming and resource draining, making them impractical for wide range application in research on childhood injury. To address the need for an efficient and valid measure that assesses injury risk due to inadequate supervision, we developed a questionnaire, the Parent Supervision Attributes Profile Questionnaire (PSAPQ).23 Questionnaires have proven to be both reliable and valid measures of many parenting behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs,24,25,26,27 making this type of instrument a promising choice for an efficient measure of supervision.

In developing the PSAPQ, a broad conceptual approach to supervision was adopted in which behaviors as well as attitudes and beliefs relevant to supervision were considered. This type of conceptual approach redirects the measurement focus from situation specific behaviors to more general patterns of supervisory styles and the underlying attributes that give rise to such styles of reacting (for example, attitudes, beliefs, values28,29,30,31) and which act to direct and constrain supervision, as well as contribute to cross situational and temporal stability in styles of supervision. Thus, the PSAPQ differs from other self report measures because it samples the underlying attributes giving rise to supervisory behavior, rather than asking respondents to report on supervisory behavior per se; there are numerous examples of the successful application of this measurement approach in diverse areas of psychology including personality32 and parenting.33,34

To develop items for the PSAPQ, literature on the topic of supervision was surveyed, supervisory behaviors as well as parenting attributes were identified, and questionnaire items were then developed to tap into these various factors. Tests were conducted both with parents, to ensure item comprehensibility, and with other professionals in the field to establish content validity (that is, adequacy of content sampled). To assess the questionnaire's criterion validity, scores on the PSAPQ were examined in relation to naturalistic observations of parent supervision, children's risk taking behaviors, and children's injury history scores.23 The PSAPQ exhibited good criterion validity: subscales significantly related to observed parental supervision and/or children's injury histories. Thus, the results from this initial study demonstrated that it was possible for parent attributes relevant to supervision and children's risk of injury to be measured reliably using a questionnaire.

Building on these initial findings, the aim of the present study was to further establish the psychometric properties of the instrument by assessing two important aspects of reliability: test‐retest reliability (that is, stability in responding over a specified time interval) and internal consistency reliability (that is, extent to which the items within a subscale measure something in common). In addition, we also sought to confirm the factor structure of the measure by assessing the construct validity for the subscales by examining if the four subscales showed adequate convergent validity (that is, that the items adequately related to their specific subscale) and divergent validity (that is, that each subscale contributed uniquely to the measurement of supervision). Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) procedures were used to assess convergent and divergent validity35 and determine if the model we specified a priori was supported by the data based on examination of the covariance structure.36

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 192 parents of children aged 2 through 5 years; children were developing normally, as reported by parents, with no known or obvious mental or physical disabilities. There was a good distribution of child ages represented in the sample, including 122 parents having a boy or girl 24–47 months of age (mean 33.5 (SD 7.4) and 34.6 (7.1) months, respectively) and 70 parents of a boy or girl 48–59 months of age (mean 54.3 (SD 7.1) and 56.5 (SD 7.9) months, respectively). The highest level of education of parents included: 10% completed some or graduated high school, 71% completed some or graduated college or university, and 19% completed some graduate training or obtained a graduate degree. The annual gross family income for participants included: 3% reporting less than $20,000; 13% reporting $20,000 to $39,000; 30% reporting $40,000 to $59,000; 25% reporting $60,000 to $79,000; and 28% reporting above $80,000. The remaining 2% of participants did not report their income. Nearly all parents were white and all spoke English as their first language. The study was reviewed and approved by the university research ethics committee and all parents granted consent for their data to be included.

Materials

Initial development and establishment of content validity of the PSAPQ included a thorough literature review to identify dimensions of parenting that seemed relevant to supervision (for example, protectiveness, risk tolerance), feedback from child development specialists about subscales and item content that tapped into these various subscales,35 and preliminary testing with parents to confirm comprehensibility of items and the response format.23 An initial test of criterion validity involved comparing PSAPQ scores with actual measures of supervision and with children's injury history scores.23 Based on these results, the PSAPQ was reduced to four factors that yielded adequate internal consistency (>0.70) and related to actual supervision and children's injury history scores. These four factors comprise 29 items (listed in table 1) tapping protectiveness (nine items), supervision beliefs (nine items), tolerance for children's risk taking (eight items), and extent of belief in fate as the primary determinant of children's safety (three items). These items were randomly ordered and presented to parents in the present study. A five point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) was used in judging each statement.

Table 1 PSAPQ factor and parcel structure by item including factor scores.

| Factor | Parcel | Factor score |

|---|---|---|

| Protectiveness | ||

| Parcel 1 | 0.75 | |

| I feel very protective of my child | ||

| I think of all the dangerous things that could happen | ||

| I keep my child from playing rough games or doing things where he/she might get hurt | ||

| Parcel 2 | 0.71 | |

| I make him/her keep away from anything that could be dangerous | ||

| I feel fearful that something might happen to my child | ||

| I warn him/her about things that could be dangerous | ||

| Parcel 3 | 0.67 | |

| I keep an eye on my child's face to see how he/she is doing | ||

| I feel a strong sense of responsibility | ||

| I try things with my child before leaving him/her to do them on his/her own | ||

| Supervision | ||

| Parcel 1 | 0.83 | |

| I have my child within arm's reach at all times | ||

| I know exactly what my child is doing | ||

| I can trust my child to play by himself/herself without constant supervision | ||

| Parcel 2 | 0.84 | |

| I stay within reach of my child when he/she is playing on the equipment | ||

| I keep a close watch on my child | ||

| I say to myself that I can trust him/her to play safely | ||

| Parcel 3 | 0.64 | |

| I stay close enough to my child that I can get to him/her quickly | ||

| I hover next to my child | ||

| I make sure I know where my child is and what he/she is doing | ||

| Risk tolerance | ||

| Parcel 1 | 0.70 | |

| I encourage my child to try new things | ||

| I let him/her learn from his/her own mishaps | ||

| Parcel 2 | 0.87 | |

| I let my child take some chances in what he/she does | ||

| I let my child do things for him/herself | ||

| I let my child experience minor mishaps if what he is doing is lots of fun | ||

| Parcel 3 | 0.74 | |

| I let my child make decisions for himself/herself | ||

| I encourage my child to take risks if it means having fun during play | ||

| I wait to see if he/she can do things on his/her own before I get involved | ||

| Fate | ||

| Items | ||

| When my child gets injured it is due to bad luck | 0.61 | |

| Whether or not my child gets injured is largely a matter of fate | 0.71 | |

| Good fortune plays a big part in determining whether or not my child gets injured | 0.92 |

Procedure

Using the same procedure as outlined previously,23 parents with young children were approached in public parks and asked to complete the PSAPQ; other questionnaire measures were also completed but will not be reported herein. For approximately 36% of the sample (n = 70), parents repeated completion of these measures one month later via the mail to assess reliability of responding (mean (SD 3.57) 3.98 weeks).

Results

Reliability

Test‐retest reliability

Test‐retest reliability was assessed using Pearson correlations and was found to be acceptable for each subscale (supervision, r(72) = 0.76, p<0.001; protectiveness, r(72) = 0.72, p<0.001; risk tolerance, r(72) = 0.76, p<0.001, and fate, r(72) = 0.80, p<0.001) over the one month interval.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach's alpha and was good for all four subscales: supervision (α = 0.77), protectiveness (α = 0.78), fate (α = 0.78), and risk tolerance (α = 0.79).

Testing for construct validity preliminary procedures

Before applying CFA procedures to assess for construct validity, individual items from protectiveness, supervision, and risk tolerance were combined into 2–3 item “parcels”; the creation of item parcels is a recommended practice in preparing for CFA.38,39,40 Item parcels are calculated by summing responses to small groupings of items within each subscale, with each item assigned to only one parcel. These aggregates, rather than individual items, function as indicator variables in the CFA model. This practice has been shown to offer a number of advantages over the use of individual items.35,36 For example, item parcels improve the sample size to parameters ratio by reducing the number of observed variables in the model. They also tend to minimize multivariate normality violations and reduce the influence of idiosyncratic response tendencies to individual items.35,37 The statistical approach recommended by Russell et al38 was implemented in the construction of item parcels. Specifically, all items from one subscale were entered into an exploratory factor analysis in which only one factor was extracted. Items were then ranked according to their loadings on this factor from highest to lowest. Groups of two or three items were summed according to their factor loadings so that the mean difference between parcels was minimized. For example one high loading item was combined with one medium and one lower loading item for each parcel. This helps to ensure that latent variables have structurally equivalent indicators (see table 1 for how specific items were parcelled). Because the fate subscale has only three items, parcelling would not have been appropriate and individual items were therefore used as indicators.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using AMOS 4 to test the construct validity of the PSAPQ. Of particular interest was the convergent and discriminant validity of the subscales. In interpreting the results, cutoff values of >0.90 for goodness of fit index (GFI), >0.95 for the comparative fit index (CFI), and <0.08 for the standardized root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were employed, as recommended.36,41,42 Results of the CFA, using maximum likelihood estimation, revealed a good model fit by all indicators. The GFI was 0.93, the CFI was 0.96, and the RMSEA was 0.06. In addition, although the χ2 was significant (48, n = 192) = 85.78, p<0.005, this statistic has been shown to be overly sensitive in studies having large sample sizes, such as in the present case. When large samples are used, therefore, the ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom, which reduces sensitivity to sample size effects, is recommended as a more appropriate indicator of model fit.36,41,42 This value was 1.79; values less than 3 are considered acceptable.36,41,42 Thus, by all indicators, the data showed a good fit to our proposed four factor model.

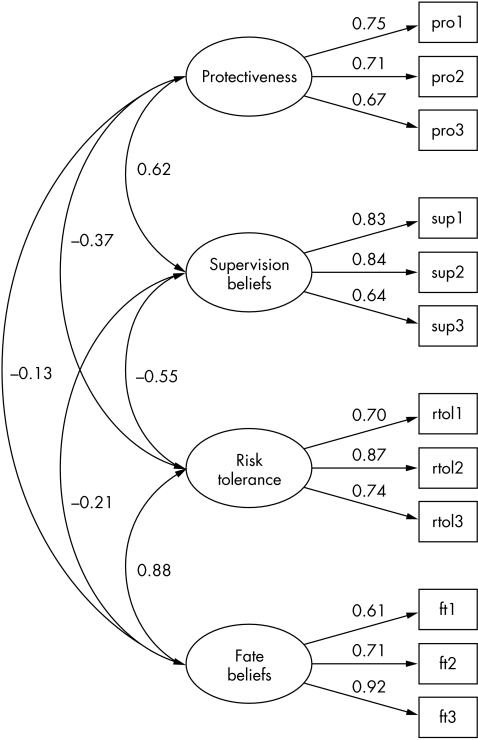

Table 1 shows the factor scores for each indicator variable. Note that all factor scores were reasonably high and significant at p<0.001. The fact that all observed variables load heavily on their factors is indicative of convergent validity. Moreover, as shown in figure 1, correlations among factors were within the acceptable range,36 showing that the factors are significantly distinct and therefore representative of different underlying constructs. Thus, the factors display a reasonably high level of discriminant validity. The highest correlation between factors was between protectiveness and supervision r(192) = 0.62, p<0.001 which was expected given that both constructs tap into a parental motivation toward harm reduction. Risk tolerance was negatively correlated with both supervision, r(192) = −0.55, p<0.001, and protectiveness r(192) = −0.37, p<0.001. Supervision was also negatively correlated with fate r(192) = −0.21, p<0.05.

Figure 1 Confirmatory factor analyses results testing the four factor model of the PSAPQ, including protectiveness, supervision beliefs, risk tolerance, and fate beliefs.

Discussion

Previous research comparing PSAPQ scores with indices of actual supervision and children's injury history scores provided evidence of both construct and predictive validity.23 The present study provides further evidence of the psychometric soundness of this new instrument, yielding information that confirms additional aspects of reliability and validity for this new instrument. First, both test‐retest reliability and internal consistency reliability were good (>0.70). Second, results confirmed that the factor structure (that is, item groupings) of the PSAPQ exhibited both convergent and discriminant validity, providing support for the four factor structure of this measure. Evidence of convergent validity for the subscales is essential and lends strong support to the notion that theoretical constructs related to supervision and injury risk can be effectively measured via a self report questionnaire instrument. Also of critical importance, evidence of divergent validity substantiates that the subscales measure independent constructs that uniquely index supervision and contribute to explain child injury risk. Thus, the hypothesized model of core attributes that contribute to caregiver supervision and relate to child injury risk was confirmed in the present test of the PSAPQ.

The pattern of correlations between the four factors of the PSAPQ confirms the unique contribution of each caregiver attribute to understanding the relation between injury risk and supervision, but also provides insights into how these attributes interrelate. The most pronounced relation is the positive one between protectiveness and supervision attributes, which is perhaps not surprising given studies have linked both higher levels of supervision17,19 and higher levels of protectiveness18,20 to lower risk of child injury. Although no studies have directly linked how caregivers supervise to measures of protectiveness, the positive relation between these attributes obtained in the present study suggest that such links likely exist. The negative correlations between the fate construct and the protectiveness and supervision constructs are consistent with previous research. To date, two studies have shown that parents who believe that their children's health and safety was predominantly a matter of luck or fate had children with a history of more frequent injuries than parents who believed that they could exercise greater control over their children's health and safety.18,43 Clearly, whether or not parents view themselves as having control over their child's safety has implications for their child's risk of injury. The present findings extend this model, however, by revealing that parents who score highly on the fate construct score lower on the protectiveness and supervision constructs on the PSAPQ. Thus, the effect of high fate beliefs on child injury risk may be realized via decreased supervision.

Key points

Caregiver supervision contributes to children's risk of injury but is difficult to measure in reliable, valid, and efficient ways.

The Parent Supervision Attributes Profile Questionnaire, a measure of supervision that comprises four factors, shows good reliability and validity.

This measure may help to identify those children at risk of injury resulting from inadequate supervision by caregivers.

The negative correlations between risk tolerance and both protectiveness and supervision constructs is also congruent with existing research. A number of studies have shown that children who engage in more risk taking behaviors tend to experience more injuries.43,44,45 It makes sense that parents who are tolerant of such risk taking would also be less likely to supervise closely or be very protective of their children. Thus, the profile of correlations between attributes on the PSAPQ are quite consistent with existing literature, lending further support to the four attribute model tested in the present study.

In summary, the findings of the present study add to the accumulating evidence that the PSAPQ is a psychometrically sound measure of caregiver supervision that has relevance for child injury risk. The pattern of associations between constructs of the PSAPQ are congruent with data from a number of sources, which lends strong support to the PSAPQ being a reliable measure of supervision related beliefs and behaviors relevant to childhood injury risk. Thus, the evidence to date indicates that this measure provides a valid, reliable, and efficient means of assessing caregiver supervision. In ongoing research, we are seeking to develop norms and cut off scores on the PSAPQ that can aid in the identification of children at risk of injury as a result of parental supervision practices, and to develop a version of the measure that is applicable to older children 6–12 years of age.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The authors extend their thanks to the parents for their enthusiastic participation and to Kate House, Natalie Johnston, and Meghan McCourt for assistance with data collection.

Abbreviations

CFA - confirmatory factor analyses

CFI - comparative fit index

GFI - goodness of fit index

PSAPQ - Parent Supervision Attributes Profile Questionnaire

RMSEA - root mean square error of approximation

References

- 1.Baker S P, O'Neil B, Ginsburg M J.et alThe injury fact book. 2nd edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1992

- 2.Canadian Institute of Child Health The health of Canada's children: A CICH profile. 3rd edition. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute of Health Research, 2000

- 3.CDC WISQARS Fatal Injuries: Leading Causes of Death Reports. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Available at http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus.html (accessed October 2005)

- 4.Shannon A, Brashaw B, Lewis J.et al Nonfatal childhood injuries: a survey at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario. Can Med Assoc J 1992146361–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alwash R, McCarthy M. How do child accidents happen? Health Educ J 198746169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garling A, Garling T. Mothers' perception of unintentional injury to young children in the home. J Pediatr Psychol 19932023–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maleck M, Guyer B, Lescohier I. The epidemiology and prevention of child pedestrian injury. Accid Anal Prev 199022301–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrongiello B A, Midgett C, Shields R. Don't run with scissors: young children's knowledge of home safety rules. J Pediatr Psychol 200126105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson L, Stern B L. Family processes and child risk for injury. Behav Res Ther 199735179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landen M G, Bauer U, Kohn M. Inadequate supervision as a cause of injury deaths among young children in Alaska and Louisiana. Pediatrics 2003111328–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrongiello B A, Lasenby J. Supervision as a behavioral approach to reducing injury risk. In: Gielen A, Sleet D, DiClemente R, eds. Handbook of injury prevention: Behavior change theories, methods, and applications. NY: Jossey‐Bass (in press)

- 12.Morrongiello B A. The role of supervision in child‐injury risk: assumptions, issues, findings, and future directions. J Pediatr Psychol 200530536–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cataldo M F, Finney J W, Richman G S.et al Behavior of injured and uninjured children and their parents in a simulated hazardous setting. J Pediatr Psychol 19921773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrongiello B A, Dawber T. Toddlers' and mothers' behaviors in an injury‐risk situation: implications for sex differences in childhood injuries. J Appl Dev Psychol 199819625–639. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garling A, Garling T. Mothers' supervision and perception of young children's risk of unintentional injury in the home. J Pediatr Psychol 199318105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrongiello B A, Dayler L. A community‐based study of parents' knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to childhood injuries. Can J Public Health 199687383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrongiello B A, Hogg K. Mothers' reactions to children misbehaving in ways that can lead to injury: implications for gender differences in children's risk taking and injuries. Sex Roles 200450103–118. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrongiello B A, Ondejko L, Littlejohn A. Understanding toddlers' in‐home injuries: I. Context, correlates, and determinants. J Pediatr Psychol 200429415–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrongiello B A, Ondejko L, Littlejohn A. Understanding toddlers' in‐home injuries: II. examining parental strategies, and their efficacy, for managing child injury risk. J Pediatr Psychol 200429433–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrongiello B, Corbett M, McCourt M.et al Understanding unintentional injury‐risk in young children: I. The nature and scope of caregiver supervision of children at home J Pediatr Psychol (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Peterson L, DiLillo D, Lewis T.et al Improvement in quality and quantity of prevention measurement of toddler injuries and parental interventions. Behav Ther 200233271–297. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson L, Tremblay G. Self monitoring in behavioral medicine. Psychol Assess 199911458–465. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrongiello B A, House K. Measuring parent attributes and supervision behaviors relevant to child injury risk: examining the usefulness of questionnaire measures. Inj Prev 200410114–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Block J.The childrearing practices report. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965

- 25.Kochanska G, Kuczynski L, Radke‐Yarrow M. Correspondence between mothers' self‐reported and observed child‐rearing practices. Child Dev 19896056–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson C, Madleco B, Olsen S.et al Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychol Rep 199577819–830. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaefer E S, Bell R Q. Development of a parental attitude research instrument. Child Dev 195829339–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slater M A, Power T G. Multidimensional assessment of parenting in single‐parent families. Advances in Family Intervention, Assessment, and Theory 19874197–228. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kochanska G, Clark L A, Goldman M S. Implications of mothers' personality for their parenting and their young children's developmental outcomes. J Pers 199365387–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mize J, Pettit G, Brown G. Mothers' supervision of their children's peer play: relations with beliefs, perceptions, and knowledge. Dev Psychol 199531311–321. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polansky N A, Gaudin J M, Jr, Ammons P W.et al The psychological ecology of the neglectful mother. Child Abuse Negl 19859265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caspi A, Roberts B W. Personality development across the life span: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry 20011249–66. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol Bull 1993113487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sigel I, McGillicuddy‐DeLisi A. Parent beliefts and cognitions: The dynamic systems model. In: Bornstein M, ed. Handbook of parenting. 2nd edition. New Jersey: Erlbaum, 2002485–508.

- 35.Nunnally J, Bernstein I.Psychometric theory. 3rd edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 1994

- 36.Kline K B.Principle and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press, 1998

- 37.Pope‐Davis D B, Vandiver B, Stone G L. White racial identity attitude development: A psychometric examination of two instruments. J Couns Psychol 19994670–79. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell D W, Kahn J H, Spoth R.et al Analyzing data from experimental studies: a latent variable structural equation modelling approach. J Couns Psychol 19984518–29. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schau C, Stevens J, Dauphinee T L.et al The development and validation of the survey of attitudes toward statistics. Edu Psychol Meas 199555868–875. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi T, Nasser F. The impact of using item parcels on ad hoc on goodness of fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis: an empirical example. In: Conference Proceedings of the American Educational Research Association 1996

- 41.Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria vs new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling 199961–55. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bentler P M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 1990107238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrongiello B A, Dawber T. Parental influences on toddler's injury‐risk behaviours: are sons and daughters socialized differently? J Appl Dev Psychol 199920227–251. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morrongiello B A, Dawber T. Mothers' responses to sons and daughters engaging in injury‐risk behaviors on a playground: implications for sex differences in injury rates. J Appl Dev Psychol 20007689–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Speltz M L, Gonzales N, Sulzbacher S.et al Assessment of injury risk in young children: a preliminary study of the injury behavior checklist. J Pediatr Psychol 199015373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]