Abstract

Objective

To determine the validity of face to face, self reported responses to questions about the presence of safety devices and use of safety practices in the home aimed at preventing unintended injuries to preschool aged children.

Methods

The authors invited families with children enrolling in a medium sized Midwestern US community Head Start program to participate in a randomized study of home safety practices. Participation involved consenting parents (n = 452) completing an initial questionnaire during Head Start enrollment or in their home. Project staff conducted home inspections to confirm parental responses to 16 questions. Only inspections conducted within 34 days of questionnaire completion (n = 259) were included in the validation study. Parents were told that the home visit would assess the need for safety devices, but were not informed of the validation aspect of the study.

Results

Sensitivities were generally high for all 16 safety practices, whereas negative predictive value and specificity varied considerably. Positive predictive value was also high for most practices, and did not vary by ethnicity. Answers provided by parents in their home were different and more reliable than those provided by parents interviewed at school (p = 0.001).

Conclusions

Use of safety devices and practices by parents of preschool aged children reported in a face to face interview are generally reliable. Reliability increases if the interview is conducted in the home. Parents may also be more willing to report potential problems if they perceive they may receive corrective assistance.

Keywords: home safety, questionnaire validation, preschool aged children, self report

Unintentional injury occurring in US homes is a major public health problem. Between 1992 and 1999, such injuries resulted in a yearly average of 18 000 fatalities.1,2 Children under the age of 15 years accounted for approximately 2100 of these deaths. Infants less than 1 year of age died most often from choking and suffocation, whereas those aged 1–14 years from burns and fires. In addition, nearly 12 million non‐fatal unintentional injuries requiring medical attention occurred in the home each year during the period of 1997 through 2001.1,2 Again, young children were one of the most vulnerable age groups, with falls as the dominant cause.1,2,3

Several factors contribute to the occurrence of unintentional injuries involving young children. Socioeconomic factors such as poverty and parental unemployment, as well as younger parental age and single marital status, increase the rate of injury.4 Some families are unaware of potential hazards or lack sufficient problem solving skills or resources to prevent harm. Environmental issues, such as housing design (presence of unguarded stairways and windows) and deferred maintenance (peeling paint, damaged wiring), increase the presence of accessible hazards.5,6 Characteristics of the child, such as gender and developmental age, influence behaviors (hand‐to‐mouth, risk taking, compliance) that also affect the risk of injury.6,7 So too, parental beliefs about their child's ability to manage risk, the inevitability of injury, and cultural influence on behavior patterns may also place the child at increased risk.4,8,9,10,11

Preventing injury in children involves recognizing how these factors affect possible intervention strategies used by parents (for example, supervision). For researchers and healthcare professionals, gaining an understanding of these perceptions is challenging. Many home injury prevention programs rely upon the use of both questionnaires and home visits to obtain relevant information. Self reported questionnaires require less effort and resources to conduct, although there may be doubts about the accuracy of the responses. Documented limitations of self reports include the length of requested recall; clarity of questions and scale of potential answers; similarity of interpretation across a broad group of individuals; cultural context; and social conformity.12,13,14,15,16 Conversely, visiting families in their homes offers an opportunity to verify the use of safety devices and practices aimed at preventing injury, and to communicate more clearly with parents.9 Home visits, however, require substantially greater resources. Designing a protocol that relies on validated self administered questionnaires would identify those families most at risk while maintaining reasonable program costs.

This study investigated the validity of responses given either at school or in the home by parents of children enrolled in Head Start programs in Dane County, Wisconsin. The study is part of a larger program aimed at evaluating assessment and intervention strategies to reduce environmental risk factors for unintentional injury, asthma, and lead exposure in the home. The safety hazards addressed in this report include burns, fires, falls, poisoning, and suffocation—all major sources of hazards for this age group.

Methods

Families of children enrolling in Dane County Head Start programs for the school years 2001–04 were eligible to participate. These programs included children ages three through five years (regular Head Start program) and birth‐to‐three years (Early Head Start program). Because of federal funding guidelines, acceptance into either of these programs is limited to families with income at or below the federal poverty level.

During initial Head Start program enrollment, or for families enrolling during the school year, project staff invited parents to respond to a questionnaire (53 questions) investigating safety behaviors and devices present and in use in the home, and their child's history of injury. We obtained written, informed consent at that time. Trained, language appropriate research staff read the questions (in English or Spanish) to the caregivers, providing additional explanation if necessary, and recorded answers. Families completed questionnaires either at the Head Start program site or in their homes (n = 808 families, 816 children). Home based questionnaire administration usually took place in a single location (that is, sitting at the kitchen table). Generally, it took less than 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire with parents. We (MLK, NMP, AGS) developed the injury questionnaire by selecting appropriate questions from the Framingham Safety Study,17 the National SAFE KIDS Campaign, and from professional experience of the authors.

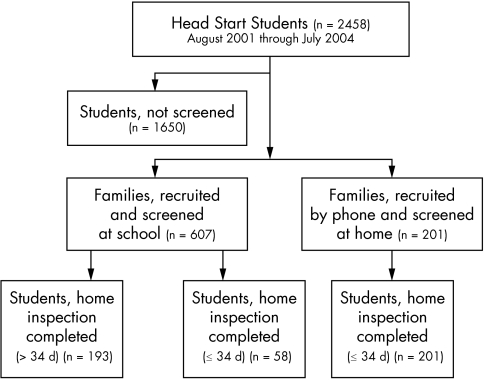

Following completion of the screening questionnaire, we invited families to participate in a research study to identify ways to prevent injuries in the home to their young children (⩽5 years of age). A summary of family recruitment, questionnaire interview, and home inspection is presented in figure 1. Participation involved a home inspection to document safety behaviors and devices currently in use, and to offer assistance in correcting identified hazards; families of 452 children agreed to a home visit. Trained staff again obtained written, informed consent from all families and subsequently inspected the bathroom, child's bedroom, kitchen, living room, and private stairs/ hallway. All parents finished a short, 20‐item written test of their knowledge of home safety issues. The home visit generally took one hour to complete. The home inspection tool (total of 226 questions) included 16 items in common with the injury questionnaire, verifiable directly by staff observation. Answers to these 16 items formed the basis for validation of the self reported injury screening questionnaire. Results are reported from all home visits conducted within 34 days following completion of the screening questionnaire (n = 259). Families approached during enrollment were unaware of the home inspection study at the time of questionnaire completion. Conversely, families interviewed at home were informed of the inspection study during recruitment. For these families, we administered the screening questionnaire followed immediately by the home inspection during the same visit.

Figure 1 Diagram of the protocol used for family recruitment, injury screening questionnaire completion, and home safety inspection.

Study personnel recorded responses provided by parents either using paper based standardized forms or electronic handheld devices (PDAs). Responses recorded on paper forms were later re‐entered on the PDAs for subsequent transfer to the study database. We used Survey Solutions inHand (Perseus Inc, Braintree, MA, USA) to develop electronic versions of the questionnaire and home inspection tool for both PDAs and the main study computer. Responses were removed from the handheld devices during transfer to the study computer. Study personnel retained completed paper based forms with other relevant materials (for example, signed consent forms) in each participant's folder, stored in a locked cabinet in a secure research facility.

We calculated sensitivity (percent true safe reported as safe), specificity (percent true unsafe reported as unsafe), positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for each of the 16 safety practices.13,14 Corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each metric were calculated using SPSS according to the method of Newcombe.18 Observations by project staff during home inspections served as true safe and unsafe.

The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Human Subjects Committee approved the study; parents/legal guardians provided written, informed consent for their child's participation. The Health Advisory Board of the Dane County Head Start similarly reviewed and approved the study objectives.

Results

The parent self reported ethnic distribution of children enrolled in the Head Start program (for 3 through 5 year olds) for the first two years of the study is shown in table 1. The majority of parents reported their children as part of an ethnic minority group, with only 15% of the children described as “White”. During the three years of the study, 808 families of enrolled children answered the injury screening questionnaire. We determined ethnicity either by observation or from parental report. The ethnic distribution of the child participants is similar to the overall Head Start population enrolled during this time period (table 1). Fewer Asian families participated in our study, perhaps because of language barriers (that is, lack of Hmong translators), whereas there was a greater interest among Hispanic families. African American families were the main ethnic group in the study, and slightly more families of female than male students participated. In addition, the majority of families listed English as the primary language spoken at home. Approximately one third of families reported only one adult residing with the child in the home; 70.4% (133/189) of interviewed parents had the equivalent of a high school education or greater.

Table 1 Characteristics of children participating in screening questionnaires (2001–04).

| Child characteristic | All Head Start Students (2001–03) | Questionnaire respondents (2001–04) | Home inspection participants (2001–04) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | (409/816) 50.1 | (216/452) 47.8 | |

| Female | (407/816) 49.9 | (236/452) 52.2 | |

| Age (months) | (422) 48.8 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | (247/1658) 14.9 | (153/787) 19.4 | (81/443) 18.3 |

| Hispanic | (373/1658) 22.5 | (233/787) 29.6 | (143/443) 32.3 |

| African American | (664/1658) 40.0 | (296/787) 37.6 | (185/443) 41.8 |

| Bi‐racial/multiracial | (259/1658) 15.6 | (53/787) 6.7 | (25/443) 5.6 |

| Asian | (112/1658) 6.8 | (30/787) 3.8 | (3/443) 0.7 |

| Native American | (3/1658) 0.2 | (6/787) 0.8 | (3/443) 0.7 |

| Other | (16/787) 2.0 | (3/443) 0.7 | |

| Primary language at home* | |||

| English | (1189/1669) 71.2 | (588/823) 71.4 | (313/450) 69.6 |

| Spanish | (351/1669) 21.0 | (212/823) 25.8 | (133/450) 29.6 |

| Asian | (106/1669) 6.4 | (23/823) 2.8 | (4/450) 0.9 |

| Number of adults in home | |||

| One | (284/783) 36.3 | (156/435) 35.9 | |

| More than One | (499/783) 63.7 | (279/435) 64.1 | |

| Average occupants in the home (783 households) 4.4 | |||

*Some families reported using two languages equally; we counted the two languages as separate occurrences.

Project staff invited families to participate during the annual on‐site enrollment period for Head Start programs; the participation rate exceeded 60% of families attending enrollment. However, during the second year of our study, Head Start enrollment procedures changed. A much smaller percentage of families attended the on‐site enrollment, requiring us to recruit enrolled families by telephone using class lists, or from referrals of Head Start staff. To recruit families at times other than enrollment, we informed them of the possibility of hazard remediation following a home inspection. For these families, we conducted the injury screening interview in their homes, followed immediately by the home inspection. Fifty six percent of participating families completed the questionnaire during school enrollment, with the remainder completing the questionnaire at home. Furthermore, 56% (452/808) of the families completing the screening questionnaire either at school or home agreed to the subsequent inspection. Many of those refusing a home visit cited lack of time, changing residencies, or lack of benefit (that is, they perceived their home to be safe).

For validation of self reported responses, we included only those inspections occurring within 34 days of questionnaire completion (n = 259). We did so to minimize the likelihood of changes in the home environment, while still maximizing the number of observations. The responses from all families completing the questionnaire (n = 808) were similar to those provided by the subset of families (n = 259) in the validation study for nine of the questions (table 2). The frequency of self reported safety practices likely differed for two of the questions because of low response rates (gun storage, toy boxes). For the remaining practices, the frequency of reported safety was higher for those responding to just the questionnaire compared with those who also underwent home inspection.

Table 2 Frequency of safety practices among all injury questionnaire respondents and home inspection participants.

| Category | % Reported safe | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire (n, %) | Home inspection (n, %) | ||

| Smoke alarm present | (776/803) 97 | (247/257) 96 | |

| Working smoke alarm | (640/760) 84 | (158/177) 89 | |

| Fire extinguisher present | (269/806) 34 | (47/255) 18 | |

| Space heater absent | (679/803) 85 | (225/259) 87 | |

| Front stove knobs absent | (546/804) 68 | (183/254) 72 | |

| Safe fire starting materials* | (716/800) 90 | (153/166) 92 | |

| Electrical outlets covered† | (425/803) 53 | (92/255) 36 | |

| No appliance use in bathroom | (425/802) 58 | (148/256) 58 | |

| Bunk beds absent | (600/797) 75 | (196/246) 80 | |

| Window guards present | (173/796) 22 | (12/153) 8 | |

| Bath tub mat present | (350/804) 44 | (77/246) 31 | |

| CO detector present | (103/800) 13 | (12/138) 9 | |

| Safe medicine storage‡ | (741/794) 93 | (65/74) 88 | |

| Safe window blind cords§ | (452/798) 57 | (50/118) 42 | |

| Safe toy box¶ | (217/354) 61 | (20/25) 80 | |

| Safe gun/ammo storage | (38/70) 54 | (4/4) 100 | |

*Storage in a locked cabinet, OR at or above adult eye level.

†All visible outlets covered completely by furniture, plugs, or special plates.

‡Storage in the bathroom in a locked cabinet, OR at or above adult eye level.

§Cords separated and shortened.

¶No lid, OR lid that stays open at any height.

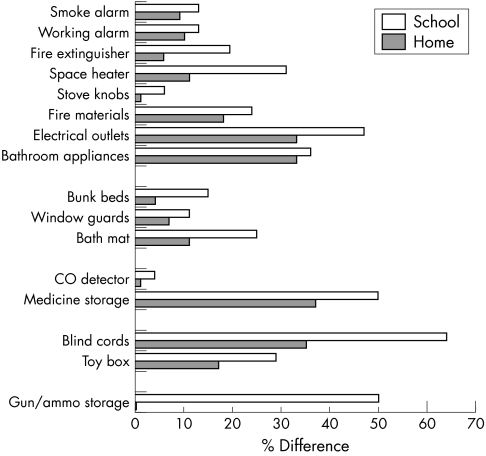

Of the 259 families completing both questionnaire and inspection within the chosen time period, 58 questionnaires (22%) were completed at school and followed by a home visit at a later date. The remaining 201 families (78%) completed both the questionnaire and inspection in the home on the same date. We found that the overall agreement between the questionnaire and the home inspection tool was significantly (p<0.001) higher when questionnaires were completed in the home. When comparing responses, sensitivity (% true safe reported as safe) was high for most of the safety practices, regardless of the location of questionnaire completion (tables 3 and 4). Positive predictive values were also generally higher than 75%. Conversely, specificity (% true unsafe reported as unsafe) and negative predictive value were somewhat more variable, with many practices characterized by values less than 75%. The response rate for approximately one quarter of the safety practices was less than 50%; for these, the hazard was generally not present in the home, and therefore the question was not applicable (that is, families denied ownership of a gun or toy box). Generally, sensitivities and specificities were higher for those questionnaire responses collected in the home compared with those collected during enrollment. Those parents answering the questionnaire at home may have been motivated to check the environment in advance of the study visit and report problems to obtain aid. Conversely, parents answering the questionnaire at school during enrollment did not expect to participate in such a survey, and so were unprepared. Nevertheless, parents in both groups experienced difficulty answering some questions—for example, the safety of window blind cords and handgun storage (fig 2).

Table 3 Comparison of paired responses between the screening questionnaire completed at school and home inspection.

| Category | Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | % Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burns/fire | |||||

| Smoke alarm present | 98 (63–100) | 17 (2–100) | 87 (58–100) | 50 (5–100) | 98 |

| Working smoke alarm | 96 (57–100) | 25 (3–100) | 90 (54–100) | 50 (5–100) | 68 |

| Fire extinguisher present | 50 (5–100) | 82 (53–100) | 11 (1–88) | 97 (62–100) | 98 |

| Space heater absent | 79 (51–100) | 0 (0–0) | 100 (63–100) | 0 (0–0) | 100 |

| Front stove knobs absent | 90 (54–100) | 100 (51–100) | 100 (59–100) | 85 (45–100) | 100 |

| Safe fire starting materials* | 96 (56–100) | 0 (0–0) | 78 (46–100) | 0 (0–0) | 70 |

| Electrical outlets covered† | 100 (6–100) | 52 (32–86) | 4 (1–32) | 100 (57–100) | 100 |

| Appliances absent in bathroom | 72 (42–100) | 47 (19–100) | 74 (43–100) | 44 (18–100) | 100 |

| Falls | |||||

| Bunk beds absent | 84 (52–100) | 89 (34–100) | 97 (59–100) | 57 (24–100) | 98 |

| Window guards present | 50 (5–100) | 92 (53–100) | 33 (4–100) | 96 (55–100) | 60 |

| Bath tub mat present | 100 (42–100) | 69 (41–100) | 48 (22–100) | 100 (57–100) | 96 |

| Poisoning | |||||

| CO detector present | 100 (20–100) | 96 (55–100) | 75 (17–100) | 100 (57–100) | 60 |

| Safe medicine storage‡ | 100 (29–100) | 0 (0–0) | 50 (17–100) | 0 (0–0) | 21 |

| Suffocation | |||||

| Safe window blind cord§ | 36 (13–99) | 38 (10–100) | 50 (17–100) | 25 (7–89) | 47 |

| Safe toy box¶ | 71 (23–100) | 0 (0–0) | 100 (29–100) | 0 (0–0) | 15 |

| Firearms | |||||

| Separate storage | 100 (6–100) | 0 (0–0) | 50 (5–100) | 0 (0–0) | 4 |

*Storage in a locked cabinet, OR at or above adult eye level.

†All visible outlets covered completely by furniture, plugs, or special plates.

‡Storage in the bathroom in a locked cabinet, OR at or above adult eye level.

§Cords separated and shortened.

¶No lid, OR lid that stays open at any height.

Table 4 Comparison of paired responses between the screening questionnaire completed in the home and home inspection.

| Category | Sensitivity % (95% CI) | Specificity % (95% CI) | PPV % (95% CI) | NPV % (95% CI) | % Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burns/fire | |||||

| Smoke alarm present | 100 (82–100) | 31 (14–68) | 91 (75–100) | 100 (38–100) | 100 |

| Working smoke alarm | 96 (75–100) | 57 (28–100) | 93 (72–95) | 71 (34–100) | 69 |

| Fire extinguisher present | 96 (57–100) | 94 (76–100) | 71 (43–100) | 99 (80–100) | 99 |

| Space heater absent | 90 (74–100) | 67 (19–98) | 99 (81–99) | 17 (6–48) | 100 |

| Front stove knobs absent | 99 (80–100) | 100 (68–100) | 100 (80–100) | 98 (66–100) | 98 |

| Safe fire starting materials* | 95 (72–100) | 23 (9–60) | 86 (66–100) | 46 (16–100) | 62 |

| Electrical outlets covered† | 100 (6–100) | 67 (54–83) | 1 (0–10) | 100 (79–100) | 98 |

| Appliances absent in bathroom | 65 (51–83) | 75 (49–100) | 90 (69–100) | 39 (27–58) | 99 |

| Falls | |||||

| Bunk beds absent | 95 (77–100) | 100 (59–100) | 100 (81–100) | 78 (48–100) | 95 |

| Window guards present | 50 (9–100) | 94 (73–100) | 22 (5–100) | 98 (76–100) | 59 |

| Bath tub mat present | 87 (57–100) | 90 (72–100) | 73 (49–100) | 96 (76–100) | 95 |

| Poisoning | |||||

| CO detector present | 100 (35–100) | 99 (75–100) | 88 (32–100) | 100 (76–100) | 52 |

| Safe medicine storage‡ | 89 (59–100) | 14 (5–41) | 63 (43–93) | 44 (14–100) | 29 |

| Suffocation | |||||

| Safe window blind cords§ | 58 (34–96) | 71 (47–100) | 59 (35–99) | 70 (46–100) | 45 |

| Safe toy box¶ | 88 (43–100) | 50 (5–100) | 93 (45–100) | 33 (4–100) | 9 |

| Firearms | |||||

| Separate storage | 100 (14–100) | 0 (0–0) | 100 (14–100) | 0 (0–0) | 1 |

*Storage in a locked cabinet, OR at or above adult eye level.

†All visible outlets covered completely by furniture, plugs, or special plates.

‡Storage in the bathroom in a locked cabinet, OR at or above adult eye level.

§Cords separated and shortened.

¶No lid, OR lid that stays open at any height.

Figure 2 Plot of the difference in agreement between paired parental self reported questionnaire responses and home inspection observations by study staff for families completing screening questionnaires at home or school.

With the diverse ethnicity of our study population, we analyzed the combined responses (school + home) to determine whether there were differences among the answers provided by White (54 families), Hispanic (79 families), and African American families (103 families). Overall, we did not detect substantial differences in the sensitivity and specificity of responses among the three racial/ethnic groups (data not shown). The specificity for presence of a smoke alarm was low for all three groups (⩽33%). Nevertheless, Hispanic families more often assumed that smoke alarms that were present were functional.

We administered a test consisting of 20 questions (multiple choice, true/false, matching) to measure parents' knowledge of potential injury hazards in the home. Items included storage of poisons and medicines, causes of falls, burns, and choking, and fire prevention. Parents generally did well on the test, scoring an average of 81% correct overall (data not shown). Specifically, 82% correctly chose a safe location for storage of cleaning products and medicines, and 80% selected “once a month” as the interval to test their smoke alarm.

Discussion

Our study of the validity of self reported home safety practices to prevent injury to preschool aged children yielded mixed results. We interviewed families either at school or in their homes, although we obtained the majority of our responses for this validation study during home interviews. Questionnaires answered in the home produced uniformly more reliable answers. Parents were likely better prepared to answer the survey questions because they had previously agreed to a home visit solely for that purpose. Moreover, we informed these parents they would receive help with injury proofing their homes, which may have provided additional motivation to report unsafe conditions. An earlier trial similarly demonstrated the overall reliability of parental reports of safety practices when surveys were mailed to participants' homes.13 Conversely, a trial of parental reports of safety practices, conducted in the clinician's office, noted that parents generally overreported the presence and use of safety devices.12 Parents interviewed at school during Head Start enrollment likewise experienced more difficulty providing accurate responses to our safety questionnaire.

Parents in both groups were generally more reliable reporting their use of a safety practice or device compared to the absence of a practice or device. For only two questions—stove knobs and CO detectors—did they provide reliable responses for both safe and unsafe conditions. Results from our knowledge tests confirmed that parents were generally well informed about most safety devices and practices.19 With some of the questions, lack of validation may have resulted from confusion by the responding parent about the nature of the safety device. The questions were read to all parents and we provided additional explanation to those who were uncertain and asked for clarification. Regardless, some parents may still have experienced some confusion. For example, window guards are uncommon in the Midwestern United States as a means to prevent access to windows. Nevertheless, insect window screens are common, and some parents may have mistaken the purpose of screens for that of guards. Low prevalence of some hazards (guns, toy boxes) also resulted in lower values of validity. And, parents may have given socially desirable responses to questions regarding generally accepted safety practices (access to fire starting materials, safe medicine storage).

Alternatively, parents may have deemed their strategy to be safe and effective. For example, in our study, parents generally reported safe storage of medicines; however, we observed substantially greater access by children than reported. Anecdotally, some parents felt their approach was safe because they had instructed the child not to touch the medicines, and they expected the child to comply.8 Had we surveyed parents about such beliefs, child characteristics, and cultural and social contexts, in addition to safety practices, we might have obtained a more complete picture of their injury prevention strategies.9,10,11,20

Our study population was quite diverse ethnically and culturally. The majority of the Hispanic families participating in our study indicated they spoke mainly Spanish at home, perhaps indicative of recent immigration. Despite this potentially complicating factor, we did not detect significant differences between the responses given by Hispanic families and those given by the other two major ethnic/racial groups. Perhaps the provision of modest assistance to the families in filling out the questionnaires aided in more reliable responses. Nevertheless, we did find that Hispanic families may be less familiar with the operation of smoke alarms. Such devices are not widely available in many less affluent countries, or are prohibitively expensive.21,22

The results of our study suggest that parental face to face, self reports of home safety practices aimed at preschool aged children can be considered reliable, although with some limitations. The overall greater sensitivity than specificity suggests that the questionnaires should be used as screening tools rather than for diagnostic purposes, as others have also concluded.12 Answers about the presence or absence of certain safety devices (for example, CO detectors) were generally more accurate than those about safety practices (for example, safe medicine storage). Future work should focus on the development of questions to verify parental agreement as to developmentally important hazards and corresponding prevention strategies. We also found that families provided more accurate responses while answering questions in their homes, suggesting that injury prevention counseling should include home visits, or allow families to complete surveys at home. The latter would eliminate some of the costs associated with home visits, while still providing accurate information. Parents interviewed in their home also had a greater expectation that their participation would lead to some improvements in home safety. This expectation may have motivated them to more readily identify existing problems. Thus, the validity of self reported questionnaires of home safety practices may be increased if the surveys are completed in the home and in a context that provides parents with hope for improvement if problems are reported.

Key points

Validating parental safety strategies is an important step in decreasing unintentional injuries.

Our results suggest the validity of self reports increases if parents respond to questionnaires while in their home. Validity may also improve if parents believe reporting problems will result in help solving those problems.

This study did not detect significant differences in the accuracy of self reports among ethnic groups, although acculturated Hispanic families may be less familiar with the operation of smoke alarms.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all members of the WHHI team for their assistance, and the participation of all of the Head Start families in this project. Other collaborators include the staff of Dane County Head Start, especially Barbara Knipfer, Mary Musholt, and Jean Rothschild. Dr Brian Goodman provided statistical guidance and analyses. This work was funded through a grant from the federal department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Healthy Homes and Lead Hazard Control, # WILHH0081‐00 (C A Sorkness).

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- 1.Home Safety Council The state of home safety in America: the facts about unintentional injuries in the home. 2002 ed. Wilkesboro, NC: Home Safety Council, 2002

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web‐based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (producer). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars (accessed October 2004)

- 3.Agran P F, Anderson C, Winn D.et al Rates of pediatric injury by 3‐month intervals for children 0 to 3 years of age. Pediatrics 2003111e683–e692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson C L, Agran P F, Winn D G.et al Demographic risk factors for injury among Hispanic and non‐Hispanic white children: an ecologic analysis. Inj Prev 1998433–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreiger J, Higgins D L. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health 200292758–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranson R. Accidents at home: the modern epidemic. In: Burridge R, Ormandy D, eds. Housing: research, remedies, and reform. New York, NY: Spon Press, 1993223–255.

- 7.Abboud dal Santo J, Goodman R M, Glik D.et al Childhood unintentional injuries: factors predicting injury risk among preschoolers. J Pediat Psychol 200429273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrongiello B A, Midgett C, Shields R. Don't run with scissors: young children's knowledge of home safety rules. J Pediat Psychol 200126105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrongiello B A, Kiriakou S. Mothers' home‐safety practices for preventing six types of childhood injuries: what do they do, and why? J Pediat Psychol 200429285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaughn E, Anderson C, Agran P.et al Cultural differences in young children's vulnerability to injuries: a risk and protection perspective. Health Psychol 200423289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulvaney C, Kendrick D. Engagement in safety practices to prevent home injuries in preschool children among white and non‐white ethnic minority families. Inj Prev 200410375–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L ‐ H, Gielien A C, McDonald E M. Validity of self reported home safety practices. Inj Prev 2003973–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson M, Kendrick D, Coupland C. Validation of a home safety questionnaire used in a randomized controlled trial. Inj Prev 20039180–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson D E. Validity of self reported data on injury prevention behavior: lessons from observational and self reported surveys of safety belt use in the US. Inj Prev 1996267–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott I. You can't believe all that you're told: the issue of unvalidated questionnaires. Inj Prev 199735–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mickalide A. Threats to measurement validity in self reported data can be overcome. Inj Prev 199737–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Pediatrics TIPP: A guide to safety counseling in office practice. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 1994

- 18.Newcombe R. Two sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: a comparative evaluation of seven methods. Stat Med 199817857–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrongiello B A, Dayler L. A community‐based study of parents' knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs related to childhood injuries. Can J Public Health 199687383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrongiello B A, House K. Measuring parent attributes and supervision behaviors relevant to child injury risk: examining the usefulness of questionnaire measures. Inj Prev 200410114–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mock C, Arreola Rissa C, Trevino Perez R.et al Childhood injury prevention practices by parents in Mexico. Inj Prev 20028303–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendrie D, Miller T R, Spicer R S.et al Child and family safety device affordability by country income level: an 18 country comparison. Inj Prev 200410338–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]