Abstract

Objective

To explore whether recent declines in household firearm prevalence in the United States were associated with changes in rates of suicide for men, women, and children.

Methods

This time series study compares changes in suicide rates to changes in household firearm prevalence, 1981–2002. Multivariate analyses adjust for age, unemployment, per capita alcohol consumption, and poverty. Regional fixed effects controlled for cross sectional, time invariant differences among the four census regions. Standard errors of parameter estimates are adjusted to account for serial autocorrelation of observations over time.

Results

Over the 22 year study period household firearm ownership rates declined across all four regions. In multivariate analyses, each 10% decline in household firearm ownership was associated with significant declines in rates of firearm suicide, 4.2% (95% CI 2.3% to 6.1%) and overall suicide, 2.5% (95% CI 1.4% to 3.6%). Changes in non‐firearm suicide were not associated with changes in firearm ownership. The magnitude of the association between changes in household firearm ownership and changes in rates of firearm and overall suicide was greatest for children: for each 10% decline in the percentage of households with firearms and children, the rate of firearm suicide among children 0–19 years of age dropped 8.3% (95% CI 6.1% to 10.5%) and the rate of overall suicide dropped 4.1% (2.3% to 5.9%).

Conclusion

Changes in household firearm ownership over time are associated with significant changes in rates of suicide for men, women, and children. These findings suggest that reducing availability to firearms in the home may save lives, especially among youth.

Keywords: firearms, guns, longitudinal, suicide, time series

In 2002, 17 108 of the 31 655 Americans who committed suicide used a firearm (54%). Men accounted for 80% of all suicides and 88% of all firearm suicides, but over 40% of all completed suicides by women and children also involved guns.1 Individual‐level case control and cohort studies in the United States suggest that the presence of a gun in the home2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and purchase of firearms from a licensed dealer14,15 are risk factors for suicide. Drawing causal inferences about the gun‐suicide connection from existing case control studies has, however, been questioned on the grounds that these studies do not adequately control for the possibility that members of gun owning households are inherently more suicidal than members of non‐gun owning households, that some individuals intent on suicide might purchase a firearm just to commit suicide, and that the association may be confounded by differential recall bias of firearm ownership and comorbid conditions (cases v controls).16,17

Ecologic studies provide a complementary approach to studying the possible relation between firearm ownership and suicide. These studies have consistently found a positive association between cross sectional measures of firearm prevalence and firearm suicide.17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 Findings with respect to the association between firearm prevalence and rates of overall suicide, however, have been mixed, depending largely on the way firearm prevalence has been measured.16,27 Ecologic studies of the firearm‐suicide connection have been criticized for using proxies to measure firearm prevalence that may be biased and, as with case control studies, on the grounds that cross sectional differences in suicidal tendencies might confound the relation between firearm prevalence and suicide.16

The possibility that people living in homes with guns are inherently more suicidal than people living in homes without guns has been addressed in case control studies by controlling for individual level psychopathology2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and in ecologic studies by controlling for aggregate level psychopathology.28,29 Nevertheless, questions remain about unmeasured characteristics that might simultaneously be associated with firearm prevalence and suicide risk. One approach to mitigating potential cross sectional confounding is to conduct longitudinal analyses, albeit at the potential cost of introducing secular distortions. To date, however, no prospective, individual‐level cohort studies have examined the firearm‐suicide connection.

The only previous time series to directly evaluate the relation between firearm ownership and suicide30 used aggregate national data on firearm ownership, 1959–84, and found a significant bivariate relation between firearm ownership and firearm suicide, but no relation between firearm ownership and overall suicide. Other ecologic time series studies abandoned direct estimates of firearm prevalence, evaluating instead the relation between firearm legislation and subsequent rates of suicide, with mixed results.31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41

Over the past decade, surveys show that the percentage of Americans living in households with firearms declined far more than it had over the previous three decades.42 The ongoing General Social Survey, for example, found that compared to the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s when roughly one in two Americans lived in homes with firearms, by 2000 the fraction had fallen to one in three. The current study is the first of which we are aware to exploit recent longitudinal variation in firearm prevalence to explore whether changes in firearm prevalence have been accompanied by significant changes in suicide by firearms, by other means, and overall.

Methods

Mortality data

Suicide mortality data were obtained through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Web‐based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS).1 These data, which were available for the years 1981–2002, were aggregated into four census regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). Suicide data, grouped by firearm (ICD‐9 E‐codes E955.0–.4, ICD‐10 E‐codes X72‐X74) and non‐firearm methods (ICD‐9 E‐codes E950–E954 and E955.5–E959; ICD‐10 E‐codes X60–X71, X75–X84, Y87.0, and U03), were further stratified by gender and age (⩽19, 20–34, 35–64, and ⩾65 years). Though coding differences between ICD‐9 and ICD‐10 preclude cross era longitudinal analyses for many causes of death, comparability ratios for suicide are nearly 1.0 and do not adversely affect our data.43

Independent variables

Analyses adjusted for age, unemployment, per capita alcohol consumption, poverty, and region of the country. Historical unemployment rate data were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics online database.44 Yearly data on regional per capita alcohol consumption were compiled by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.45 The percent of the population below poverty in each year of the study period was found in the Historical Poverty Table derived from the US Census Bureau's Current Population Survey.46

Estimates of regional household firearm ownership rates are from the General Social Survey (GSS).42 GSS household gun ownership data were available for the years 1982, 1984, 1985, 1987–1991, 1993, 1994, 1996–2002; estimates of household gun ownership for missing years were imputed using the average of the adjacent years. For the population as a whole we derived firearm ownership estimates based on all respondents (that is, pooled responses from male and female respondents), the most common measure used in previous work using this survey.

The decrease in the prevalence of household firearm ownership derived using responses from both sexes does not necessarily reflect the actual change in household firearm ownership for either sex. For example, if married men left their wives beginning in 1990, and took their guns with them, all else equal, the percentage of men living in households with guns would not change, but the percentage of women in households with guns would drop dramatically. To more accurately capture the exposure to household firearms for men and for women separately, we derived household firearm prevalence estimates for women using responses in the GSS from women only (and for men, using responses from men only). We also derived estimates of household firearm ownership for homes with children based on responses of adults who reported living in households with children 18 years of age or younger.

Parsing our exposure measure in this way has additional advantages. It allowed us to account for the well established observation that firearm prevalence estimates for two‐adult households based on survey responses from males only are significantly higher than estimates derived using responses from women only.47,48 It also takes into account the possibility that this gender related reporting gap may change over time. In addition, it reflects the assumption that a household gun used in a suicidal act is a gun the suicidal individual knew was in the home.

Because our independent variable “household firearm ownership” takes on different values for each region‐year depending on whether it is based on responses from both sexes jointly or separately, our point estimates in regressions on the population as a whole are not directly comparable to point estimates from regressions on males and females separately.

Analyses

To account for the non‐independence of repeated measures from the same census region over time, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) models in our multivariate analyses.49 These models build upon generalized linear models and are designed to estimate accurate regression coefficients for longitudinal data by allowing specification of both the link function and correlation structure. Standard errors of the regression parameters are computed using the Huber‐White sandwich estimator of variance to account for the within‐region correlation of outcome using GEE.50,51 Results are as if there were a cluster option and we specified clustering on region. Regional fixed effects models were used to account for unobserved time invariant factors that might explain regional differences in rates of suicide. All models adjust for age, unemployment, per capita alcohol consumption, and poverty.

We present results of log‐log regressions to express the percent change in the dependent variable (for example, firearm suicide rate) for a 10% change in household firearm ownership. Results obtained using GEE are similar to those obtained using regional fixed effects negative binomial models that adjust for serial autocorrelation over time within each census region (not shown).

Results

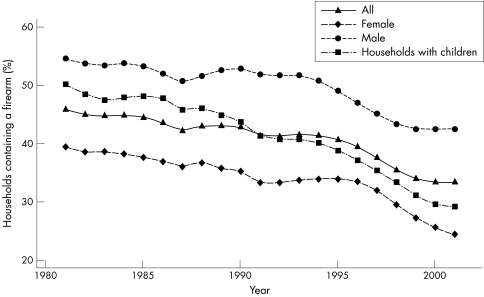

Over the 22 year study period, household firearm ownership rates declined across all four regions, with declines averaging 1.5% per year for the nation as a whole (in absolute terms, 0.6 percentage points per year) (fig 1). The absolute percentage of men who report living in homes with firearms was always greater than both the percentage of women who report living in homes with firearms and the percentage of adults with children living in homes with firearms. The relative decline in the percentage of men who report living in homes with firearms was slightly less than the decline for women and for children, averaging, respectively 1.3%, 2.1%, and 2.7% per year (fig 1).

Figure 1 Three year rolling averages of household gun prevalence in the United States, 1981–2002.

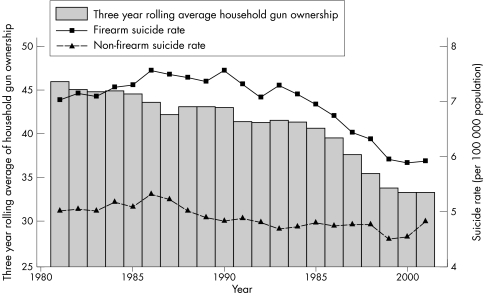

For the nation as a whole, declines in the percentage of American households containing firearms were accompanied by declines in rates of suicide by firearm (fig 2); changes in non‐firearm suicide rates were not significantly related to changes in household firearm prevalence. The steepest declines in household firearm prevalence and in firearm suicide occurred over the second decade of the study period (figs 1 and 2).

Figure 2 Household gun ownership levels and rates of firearm and non‐firearm suicide mortality: United States, 1981–2002.

In multivariate analyses, each 10% decline in firearm prevalence was accompanied by significant declines in suicide by firearm and suicide overall: firearm suicide rates dropped by 4.2% (95% CI 2.3% to 6.1%) and total suicide rates by 2.5% (95% CI 1.4% to 3.6%) (table 1). The rate of non‐firearm suicide was not significantly related to changes in firearm prevalence for the population as a whole, for men, for women, or for children. The magnitude of association between the relative changes in household firearm ownership and rates of suicide due to firearms did not differ significantly across gender. The magnitude of the association between changes in household firearm prevalence and rates of firearm and overall suicide was greatest for children: for each 10% decline in the percentage of households containing both children and firearms, the rate of firearm suicide among children 0–19 years of age dropped 8.3% (95% CI 6.1% to 10.5%) and the rate of overall suicide dropped 4.1% (2.3% to 5.9%).

Table 1 Longitudinal association between household gun ownership and suicide mortality: percent decrease in mortality rate for each 10% decrease in household firearm ownership level (1981–2001), adjusted for age, unemployment, poverty, per capita alcohol consumption, and region of the country.

| % Decrease in firearm suicide rate (95% CI) | % Decrease in non‐firearm suicide rate (95% CI) | % Decrease in overall suicide rate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 4.2% (2.3%–6.1%)*** | 0.3% (−1.4%–2.3%) | 2.5% (1.4%–3.6%)*** |

| Males | 3.4% (2.8%–4.1%)*** | 1.1% (−0.7%–2.9%) | 2.3% (1.7%–2.9%)*** |

| Females | 3.4% (1.9%–4.9%)*** | −0.5% (−1.9%–1.9%) | 1.0% (0.4%–1.6)** |

| Children (0–19 years of age) | 8.3% (6.1%–10.5%)*** | −0.4.% (−2.9%–2.1%) | 4.1% (2.3%–5.9%)*** |

Discussion

Consistent with previous individual level studies,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,14,15 as well as with some17,18,20,21,22,23,24,29,52 but not all19,25 cross sectional ecologic studies, we find that higher rates of firearm ownership are associated with higher rates of overall suicide. For all groups, the relation between changes in household firearm ownership and changes in overall rates of suicide is due to the association between changes in firearm ownership and changes in suicide by firearms (that is, changes in non‐firearm suicide are not related to changes in rates of firearm ownership). Our finding that the magnitude of association between household firearm ownership and suicide is particularly high for children is consistent with previous empirical work,10,19,23,53 and with the hypothesis that suicide acts by youth are more likely to be impulsive and therefore more likely to be affected by the means at hand.54,55

Our findings are also consistent with some31,32,33 but not all,30,34 previous national longitudinal studies (all but one of which examined the relation between suicide rates and firearm related legislation rather than the relation between suicide rates and firearm prevalence directly). Relative to previous US studies, our longitudinal study focused on a time period during which there was a marked downward trend in household firearm prevalence. This statistical advantage made it less likely that an actual association between firearm prevalence and rates of suicide would be obscured by random error involved in measuring firearm prevalence. This advantage may explain, in part, why we found a significant relation between changes in firearm prevalence and rates of suicide when the only previous US study to directly investigate the association between firearm prevalence and suicides found none.30 In addition, that previous study did not control for other factors and used firearm ownership data from two different sources (Gallop and NORC polls) over a period during which firearm prevalence changed little relative to the measurement error associated with estimating prevalence.

The current study is the first longitudinal evaluation we are aware of to specifically render the exposure of interest—household firearm prevalence—separately for men, women, and children. By doing so we are better able to account for the possibility that changes in household firearm prevalence might differ for these distinct groups (as might have occurred, for example, because of changes in household composition over time). In addition, we are able to control for potential regional variation in rates of change in firearm prevalence and suicide over time.

Although our ecologic approach avoids the case control problem of recall bias (for example, cases being more likely to accurately recall a firearm in the home than controls), this benefit comes at the possible interpretative cost of assuming that group‐level associations reflect individual risk factors (that is, the ecologic fallacy).56 The greatest threat to the validity of our findings in this respect is that we do not know whether firearm suicide victims actually lived in homes with guns. Findings from case control studies, however, suggest that firearm suicide victims overwhelmingly use guns from their own home.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,14,15 For example, in one study of suicides in the home10 and in another of adolescent suicides in and out of the home,6 approximately 90% of victims used a gun if they lived in a home with a gun. In addition, fewer than 10% of all firearm suicides involved a firearm from a home other than the victim's household.10

Our analyses adjust for rates of poverty, unemployment, per capita alcohol consumption, the age distribution of the population, and census region, but many other factors may affect suicide rates. We could think of no obvious covariates that, were they included, would a priori explain the specificity of our findings—that changes in firearm suicide (but not non‐firearm suicide) correlate with changes in firearm ownership. The covariate we most would have liked to directly account for in our analyses is one that captured annual changes in suicidality over time. Unfortunately, no such data are available. However, the largest study ever to address secular trends in the mental health of Americans found no national changes in suicidal tendencies between 1990 and 200057—precisely the period of our study during which suicide rates (and firearm ownership) declined most steeply. In addition, previous cross sectional ecologic studies have found that measures of psychopathology (for example, major depression, serious suicidal thoughts) do not appear to be associated with rates of household firearm ownership29 and that controlling for suicide attempt rates does not mitigate the gun‐suicide connection.53

Our study has additional limitations. Although we used survey measures of household firearm ownership, this measure does not provide potentially important information about many characteristics of firearm availability that may be related to the rate of suicide deaths. For example, our measure does not provide information about the relative prevalence of handguns and long guns, the number of firearms in a gun owning household, firearm storage practices, access to illegal firearms, familiarity with firearms, the caliber of gun(s), how often guns are used for other purposes such as hunting or target practice, or changes in the social acceptability of suicide by firearms over time. In addition, survey research has found that many women, some living in two‐adult households with guns, may not have accurate information about whether a gun is present in their home.48,58 That we find significant associations between suicide and firearm prevalence regardless of whether prevalence estimates are derived from men or women or all respondents suggests that reporting differences by gender do not account for our results.

Despite these limitations, we find changes in household firearm ownership over time were associated with significant changes in rates of suicide for men, women, and children, controlling for the region of the country in which they lived and independent of rates of unemployment, poverty, and alcohol consumption. The relation between changes in household firearm ownership and overall rates of suicide is due to the association of firearm ownership and suicide by firearms (that is, changes in non‐firearm suicide are not related to changes in firearm ownership). Consistent with our findings, a recent systematic review of all suicide prevention studies published between 1966 and 200559 concluded that restricting access to lethal means is one of only two suicide prevention strategies shown to prevent suicide. This conclusion, however, is at odds with the view held by many Americans—that restricting access to highly lethal means is unlikely to save many lives.60

The presumption is that anyone serious enough about suicide to use a gun or jump off a bridge will inevitably find another way to take his own life. Results from our longitudinal study, combined with findings from previous case control, cohort, and ecologic studies fundamentally undercut this presumption. In a nation where over half of all suicides are due to guns, restricting ready access to household firearms is likely to save many lives, especially among children.

Key points

Consistent with previous cross sectional case control and ecologic studies, this time series analysis finds a significant relation between household firearm ownership and rates of suicide overall and by firearms.

Changes in household firearm ownership over time are associated with significant changes in rates of suicide for men, women, and children.

These findings suggest that reducing availability to firearms in the home may save lives, especially among youth.

Acknowledgements

Dr Miller assumes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. Drs Miller, Azrael, and Hepburn made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study as well as to the analysis and interpretation of data. Mr Lippmann played a major role in the acquisition and analysis of data. Dr Miller wrote the manuscript; Drs Hemenway, Azrael, Hepburn, and Mr Lippmann revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval to the version here submitted. None of us has any financial interests related to the work submitted. Dr Miller had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the work presented. Funding for this project was provided by the Joyce Foundation.

Abbreviations

GEE - generalized estimating equations

GSS - General Social Survey, WISQARS, Web‐based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Web‐based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Available at www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars (accessed April 2005)

- 2.Dahlberg L L, Ikeda R M, Kresnow M J. Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: findings from a national study. Am J Epidemiol 2004160929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brent D A, Perper J A, Goldstein C E.et al Risk factors for adolescent suicide. A comparison of adolescent suicide victims with suicidal inpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 198845581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent D A, Perper J A, Moritz G.et al Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case‐control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 199332521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brent D A, Perper J A, Allman C J.et al The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides. A case‐control study. JAMA 19912662989–2995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brent D A, Perper J A, Moritz G.et al Suicide in affectively ill adolescents: a case‐control study. J Affect Disord 199431193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brent D A, Perper J A, Moritz G.et al Firearms and adolescent suicide. A community case‐control study. Am J Dis Child 19931471066–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brent D A, Perper J, Moritz G.et al Suicide in adolescents with no apparent psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 199332494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conwell Y, Duberstein P R, Connor K.et al Access to firearms and risk for suicide in middle‐aged and older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 200210407–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellermann A L, Rivara F P, Somes G.et al Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med 1992327467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey J E, Kellermann A L, Somes G W.et al Risk factors for violent death of women in the home. Arch Intern Med 1997157777–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiebe D J. Homicide and suicide risks associated with firearms in the home: a national case‐control study. Ann Emerg Med 200341771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bukstein O G, Brent D A, Perper J A.et al Risk factors for completed suicide among adolescents with a lifetime history of substance abuse: a case‐control study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 199388403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings P, Koepsell T D, Grossman D C.et al The association between the purchase of a handgun and homicide or suicide. Am J Public Health 199787974–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wintemute G J, Parham C A, Beaumont J J.et al Mortality among recent purchasers of handguns. N Engl J Med 19993411583–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Research Council Firearms and suicide. In: Wellsford C, Pepper J, Petrie C (eds). Firearms and violence: a critical review. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2005152–200.

- 17.Killias M. International correlations between gun ownership and rates of homicide and suicide. Can Med Assoc J 19931481721–1725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markush R E, Bartolucci A A. Firearms and suicide in the United States. Am J Public Health 198474123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sloan J H, Rivara F P, Reay D T.et al Firearm regulations and rates of suicide. A comparison of two metropolitan areas. N Engl J Med 1990322369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birckmayer J, Hemenway D. Suicide and firearm prevalence: are youth disproportionately affected? Suicide Life Threat Behav 200131303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Household firearm ownership and suicide rates in the United States. Epidemiology 200213517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and suicide, homicide, and unintentional firearm deaths among women. J Urban Health 20027926–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and unintentional firearm deaths, suicide, and homicide among 5–14 year olds. J Trauma. 2002;52: 267–74; discussion 274–5, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Lester D. Availability of guns and the likelihood of suicide. Sociol Soc Res 198771287–288. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lester D. Gun ownership and suicide in the United States. Psychol Med 198919519–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan M S, Geling O. Firearm suicides and homicides in the United States: regional variations and patterns of gun ownership. Soc Sci Med 1998461227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller M, Hemenway D. The relationship between firearms and suicide: a review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav 1999459–75. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. The epidemiology of case fatality rates for suicide in the northeast. Ann Emerg Med 200443723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hemenway D, Miller M. Association of rates of household handgun ownership, lifetime major depression, and serious suicidal thoughts with rates of suicide across US census regions. Inj Prev 20028313–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clarke R V, Jones P R. Suicide and increased availability of handguns in the United States. Soc Sci Med 198928805–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lester D. Firearm availability and the incidence of suicide and homicide. Acta Psychiatr Belg 198888387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrington P, Moyer S. Gun control and suicide in Ontario. Am J Psychiatry 1994151606–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loftin C, McDowall D, Wiersema B.et al Effects of restrictive licensing of handguns on homicide and suicide in the District of Columbia. N Engl J Med 19913251615–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rich C, Young J, Fowler R.et al Guns and suicide: possible effects of some specific legislation. Am J Psychiatry 1990147342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lester D, Leenaars A. Suicide rates in Canada before and after tightening firearm control laws. Psychol Rep 199372787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwig J, Cook P J. Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. JAMA 2000284585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cummings P, Grossman D C, Rivara F P.et al State gun safe storage laws and child mortality due to firearms. JAMA 19972781084–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webster D W, Vernick J S, Zeoli A M.et al Association between youth‐focused firearm laws and youth suicides. JAMA 2004292594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosengart M, Cummings P, Nathens A.et al An evaluation of state firearm regulations and homicide and suicide death rates. Inj Prev 20051177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conner K R, Zhong Y. State firearm laws and rates of suicide in men and women. Am J Prev Med 200325320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beautrais A L, Fergusson D M, Horwood L J. Firearms legislation and reductions in firearm‐related suicide deaths in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 200640253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis J A, Smith T W. General Social Surveys (GSS), 1972–2002 [machine readable data file]. Sponsored by National Science Foundation; NORC, ed. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center [producer]; Storrs, CT, The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut [distributor] 2004

- 43.Anderson R N, Minino A M, Hoyert D L.et al Comparability of cause of death between ICD‐9 and ICD‐10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2001491–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bureau of Labor Statistics Regional Unemployment Rate Statistics, 1976–2004. 2005 [cited 2005 July 15]. Available at http://www.data.bls.gov (accessed March 2006)

- 45.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Per capita ethanol consumption for states, census regions, and the United States, 1970–1998 [table]. Available at http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/databases/consum03.txt (accessed January 2005)

- 46.US Census Bureau Historical Poverty Tables, Poverty of People, by Region: 1959–2003 from the Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. 2005 [cited 2005 August 1]; Available at http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/histpov/hstpov9.html

- 47.Azrael D, Miller M, Hemenway D. Are household firearms stored safely? It depends on whom you ask. Pediatrics 2000106E31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ludwig J, Cook P J, Smith T W. The gender gap in reporting household gun ownership. Am J Public Health 1998881715–1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diggle P, Liang K, Zeger S.Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994

- 50.Huber P. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non‐standard conditions. In: Fifth Berkeley Symposium on mathematical statistics and probability. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1967

- 51.White H. A heteroskedasticity‐consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 198048817–838. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Rates of household firearm ownership and homicide across US regions and states, 1988–1997. Am J Public Health 2002921988–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller M, Hemenway D, Azrael D. Firearms and suicide in the Northeast. J Trauma 200457626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horesh N, Gothelf D, Ofek H.et al Impulsivity as a correlate of suicidal behavior in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Crisis 1999208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kashden J, Fremouw W J, Callahan T S.et al Impulsivity in suicidal and nonsuicidal adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 199321339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piantadosi S. Invited commentary: ecologic biases. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139: 761–4; discussion 769–71, [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Kessler R C, Demler O, Frank R G.et al Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med 20053522515–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Azrael D, Hemenway D. ‘In the safety of your own home': results from a national survey on gun use at home. Soc Sci Med 200050285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mann J J, Apter A, Bertolote J.et al Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 20052942064–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Belief in the inevitability of suicide: results from a national survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2006361–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]