Abstract

Background

Evidence indicates that point of purchase (POP) advertising and promotions for cigarettes have increased since the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA). Retail promotions have the potential to offset the effects of cigarette tax and price increases and tobacco control programmes.

Objective

To describe the trend in the proportion of cigarette sales that occur as part of a POP promotion before and after the MSA.

Design

Scanner data were analysed on cigarette sales from a national sample of grocery stores, reported quarterly from 1994 through 2003. The proportion of total cigarette sales that occurred under any of three different types of POP promotions is presented.

Results

The proportion of cigarettes sold under a POP promotion increased notably over the sample period. Large increases in promoted sales are observed following implementation of the MSA and during periods of sustained cigarette excise tax increases.

Conclusions

The observed pattern of promoted cigarette sales is suggestive of a positive relationship between retail cigarette promotions, the MSA, and state cigarette tax increases. More research is needed to describe fully the relationship between cigarette promotions and tobacco control policy.

Keywords: cigarette promotions, Master Settlement Agreement, policy, scanner data

A majority of cigarette company advertising and promotional expenditures has been devoted to the retail channel since 1988, making it the dominant medium for marketing cigarettes in the USA. In 2002, the four largest expenditure categories for cigarette advertising and promotion were again focused on the retail environment. They are price discounts ($7.9 billion, 63.2% of total); promotional allowances to retailers to facilitate product placement ($1.3 billion, 10.7% of total); retail value added programmes with bonus cigarettes, such as buy‐one‐get‐one‐free (BOGO) offers ($1.06 billion, 8.5% of total); and coupons ($522 million, 4.2% of total).1

The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) may have increased the importance of the retail channel by banning the use of billboards, transit advertising, and cartoon characters and by placing limits on event sponsorships.2 Since the MSA, increases in interior and exterior tobacco advertising3,4 and higher prevalence of point of purchase (POP) promotions have been reported.3 Participation in cigarette company incentive programmes is associated with increased levels of cigarette advertising and lower average prices for at least some brands of cigarettes.5,6 In addition, evidence suggests that cigarette manufacturers may use POP promotions as a means to attenuate the effects of comprehensive tobacco control programmes and cigarette price increases.7,8,9,10

Several studies describe the quantity and type of cigarette advertising in retail stores,3,4,5,6,11,12,13,14,15,16 but to date nothing has been reported in the public health literature about the volume of cigarette sales occurring under a POP promotion or the change in promoted cigarette sales over time. In this brief report, we describe the trend in the proportion of cigarettes sold under a POP promotion using sales data collected in a nationwide sample of grocery stores in the USA from 1994 through 2003. We describe changes in promoted sales before and after the MSA and during periods of sustained cigarette tax increases.

METHODS

Cigarette sales are derived from scanner data licensed from ACNielsen.17 The data are collected in a national sample of grocery stores with at least $2 million in annual sales (about $5500 per day) and are reported quarterly from 1994 through 2003. The data report total cigarette sales, in packs, as well as sales for three kinds of POP promotions: (1) bonus cigarettes (for example, buy one pack, get one pack free); (2) bonus merchandise (for example, buy two packs, get a free lighter); and (3) price discounts (for example, price reduced by 25¢ per pack). We summed the pack sales occurring under any of the three promotions and divided by total pack sales to obtain the proportion of cigarette sales occurring under a POP promotion in each calendar quarter.

Between 1994 and 2002, grocery stores accounted for only 12.4% of cigarette sales volume, on average, compared with 75% for convenience stores and convenience/gas combinations.18 Approximately 45% of cigarettes sold in grocery stores are sold by the carton; less than 1% of convenience store sales are cartons. Because of these differences, we compared promoted sales in grocery stores to promoted sales in convenience stores (data from ACNielsen). Scanner data from convenience stores are expensive and difficult to obtain, limiting the comparison sample to five selected market areas (Detroit; Miami; Phoenix; Portland, Oregon; and Raleigh/Durham, North Carolina) in five quarters (1998−Q4 to 1999−Q4). In these markets, promoted sales in grocery stores averaged 1.7% of total sales (range 0.9% to 2.8%), compared with 2.1% (range 1.2% to 3.0%) in convenience stores (p < 0.001). Promoted sales in grocery stores were lower in four out of five quarters, averaging 0.3 percentage points less than promoted sales in convenience stores (range –1.1% to 0.4%). The correlation between promoted sales in convenience stores and grocery stores was ρ = 0.69 (p < 0.001), indicating a fairly strong linear relationship. Nonetheless, the proportion of promoted sales in grocery stores likely underestimates the true level of promoted sales in the overall cigarette market.

Data on cigarette excise tax changes are from The tax burden on tobacco.19 Tax changes are coded in the calendar quarter in which they actually occur.

RESULTS

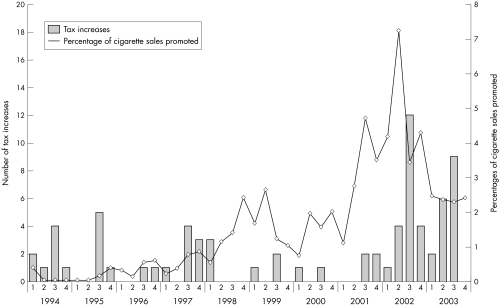

Figure 1 shows the share of promoted cigarette sales in grocery stores and the number of state cigarette tax increases in each calendar quarter from 1994 through 2003. The figure shows that promoted sales first peaked in the fourth quarter of 1998 at 2.4% of total sales, coinciding with the signing of the MSA. From that time, promoted sales are fairly stable at a quarterly average of 2.3% until spiking again to 4.7% in the third quarter of 2001. Between the third quarter of 2001 and the end of 2003, promoted cigarette sales averaged 3.7% of total sales, with a maximum of 7.3% in the second quarter of 2002.

Figure 1 Promoted cigarette sales in grocery stores and number of state cigarette excise tax increases, USA, 1994–2003.

The figure also shows that the period of high promotional sales beginning in 2001 overlaps with a period of sustained increases in state cigarette taxes. There were 36 cigarette tax increases from 2001 through 2003, more than occurred from 1994 through 2000 combined.19 Twelve states increased their cigarette tax in the third quarter of 2002 alone, one quarter after the observed peak in promoted cigarette sales.

In 2002, the year with the highest level of promotional sales, 1.9 billion packs of cigarettes were sold in grocery stores in the USA. Of these, 91.4 million packs (4.81%) were sold under a POP promotion. Applying this percentage to total cigarette consumption of 20.75 billion packs1 gives 997.6 million packs sold under a POP promotion, or 3.46 packs per person. At 2002 retail prices, the value of cigarettes given away in grocery stores under BOGO‐type promotions was $126.2 million. If the proportion of cigarettes given away under a BOGO promotion is the same across all outlets as in grocery stores, then the retail value of all cigarettes given away as part of a BOGO was approximately $1.4 billion in 2002. This is reasonably close to the $1.06 billion the industry reported spending on “retail value added—bonus cigarettes” promotions in 2002.1

DISCUSSION

The data show that the level and variability of promoted cigarette sales in grocery stores have increased notably from 1994 to 2003. The increase in promotional sales in 1998 and 1999 is suggestive of an association with the MSA and is consistent with evidence showing increases in retail advertising after the MSA.3,4 Our data also show an increase in promoted sales during a period of increases in state cigarette taxes.

Since the MSA, several states have launched comprehensive tobacco control programmes. Nationally, annual spending for tobacco control programmes increased from approximately $1.24 per person to $2.72 per person, an increase of 119%, from 1998 to 2002. Increases in cigarette promotions during periods of strengthening tobacco control programmes are consistent with previous results that cigarette POP promotions are more likely in states with comprehensive tobacco control programmes.7,9 There is ample evidence of industry opposition to tobacco control programmes and policies,10,20,21,22,23,24 and the industry exerts considerable political influence.25 Given its past behaviour, an effort by the tobacco industry to blunt the effect of the MSA and other tobacco control policies with retail promotions cannot be discounted.

The competitive nature of the cigarette industry is also a determinant of advertising and promotional expenditures. Concentrated industries such as the tobacco industry tend to compete based on advertising rather than on price.26 Therefore, as cigarette sales continue to fall, all firms in the industry may react with increased advertising. Between 1996 and 2002, cigarette sales fell by 22.2% and total advertising expenditures rose by 144%.1 In addition, since the MSA, the retail channel is one of the few remaining options for tobacco advertising, and so it attracts a growing share of all advertising resources.27

What this paper adds

Increases in the number of internal and external cigarette advertisements in retail stores since the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) have been documented. Researchers have also noted that the prevalence of certain retail promotions are higher in states with comprehensive tobacco control programmes. Retail promotions may offset the effects of cigarette tax and price increases and tobacco control programmes.

This brief report describes the proportion of cigarette sales that occur under a point of purchase promotion in grocery stores in the USA between 1994 and 2003. Our results show that the share of promoted cigarette sales increased substantially over the study period and suggest that some of the increase may be in response to the MSA and rapidly increasing state cigarette excise taxes.

Regardless of the underlying reasons for the observed pattern of promoted cigarette sales, increasing POP cigarette promotions are a concern for the public health community. Evidence suggests that retail marketing for the most popular youth brands (Marlboro, Camel, and Newport) may be more prevalent in stores frequented by youth.13 Frequent exposure by youth to retail tobacco advertising has been associated with higher prevalence rates of youth lifetime smoking.14 Cigarette advertising in general may increase total cigarette sales,26 and increased advertising expenditures since the MSA have been successful in partially offsetting the effects of higher prices resulting from the settlement.28

This study has several limitations. Because our data are from grocery stores only, we likely underestimate the true level of promotional sales across all retail outlets, as the above comparison with convenience stores demonstrates. The scanner data only contain information on promotions that are captured at the checkout register via a unique universal product code. As described previously, these include bonus cigarettes, bonus merchandise, and price discounts. Bonus cigarette promotions and bonus merchandise promotions are probably almost completely captured by the scanner data. However, if a retailer simply lowers cigarette prices because of participation in an incentive programme, this will not be captured in the scanner data as a distinct promotion. Finally, some of the observed increase in percentage of sales that occur under a promotion may be the result of smokers seeking better deals in response to price and tax increases. Not all of the variation is due to cigarette manufacturers offering more promotions.

Several studies have described the nature and type of cigarette advertising and promotions in retail stores. This paper is the first to describe the trend in promoted cigarette sales. Further research is needed to rigorously disentangle the individual contributions of the MSA, tobacco control policies, and intra‐industry competition to the observed increase in promotional sales and to estimate the effect of promotions on smoking rates among youth and adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Preparation of this paper was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Substance Abuse Policy Research Program.

Abbreviations

BOGO - buy‐one‐get‐one‐free

MSA - Master Settlement Agreement

POP - point of purchase

Footnotes

Competing interests: none to declare

*RTI International is a trade name of Research Triangle Institute

References

- 1.Federal Trade Commission ( F T C ) Federal Trade Commission cigarette report for 2002, released in 2004. http://www.ftc.gov/reports/cigarette/041022cigaretterpt.pdf (Accessed Oct 22, 2004)

- 2.Tobacco Control Resource Center The multistate Master Settlement Agreement and the future of state and local tobacco control: an analysis of selected topics and provisions of the multistate Master Settlement Agreement of November 23, 1998. In: Kelder G, Davidson P, eds. The Tobacco Control Resource Center, Inc. Northwestern University School of Law 1999

- 3.Wakefield M A, Terry‐McElrath Y M, Chaloupka F J.et al Tobacco industry marketing at point of purchase after the 1998 MSA billboard advertising ban. Am J Public Health 200292937–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celebucki C C, Diskin K. A longitudinal study of externally visible cigarette advertising on retail storefronts in Massachusetts before and after the Master Settlement Agreement. Tob Control 200211(suppl II)ii47–ii53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feighery E C, Ribisl K M, Clark P I.et al How tobacco companies ensure prime placement of their advertising and products in stores: interviews with retailers about tobacco company incentive programs. Tob Control 200312184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feighery E C, Ribisl K M, Schleicher N C.et al Retailer participation in cigarette company incentive programs is related to increased levels of cigarette advertising and cheaper cigarette prices in stores. Prev Med 200438876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaloupka F, Slater S, Wakefield M. USA: price cuts and point of sale ads follow tax rise. Tob Control 19998242–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keeler T E, Hu T ‐ W, Barnett P G.et al Do cigarette producers price‐discriminate by state? An empirical analysis of local cigarette pricing and taxation. Journal of Health Economics 199615499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slater S, Chaloupka F J, Wakefield M. State variation in retail promotions and advertising for Marlboro cigarettes. Tob Control 200110337–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaloupka F J, Cummings K M, Morley C P.et al Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control 200211(suppl I)i62–i72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbeau E M, Wolin K Y, Naumova E N.et al Tobacco advertising in communities: associations with race and class. Prev Med 20054016–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feighery E C, Ribisl K M, Schleicher N.et al Cigarette advertising and promotional strategies in retail outlets: results of a statewide survey in California. Tob Control 200110184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henriksen L, Feighery E C, Schleicher N C.et al Reaching youth at the point of sale: cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently. Tob Control 200413315–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henriksen L, Feighery E C, Wang Y.et al Association of retail tobacco marketing with adolescent smoking. Am J Public Health 2004942081–2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laws M B, Whitman J, Bowser D M.et al Tobacco availability and point of sale marketing in demographically contrasting districts of Massachusetts. Tob Control 200211(suppl II)ii71–ii73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoek J. Tobacco promotion restrictions: ironies and unintended consequences. Journal of Business Research 2004571250–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACNielsen Scan‐Trac™ Data, Grocery Channel, Total United States, 1994–2003. 2003

- 18.R J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. http://www.rjrt.com/IN/COwhoweare_themarket.asp (Accessed Oct 27, 2004)

- 19.Orzechowski and Walker The tax burden on tobacco, historical volume 38. Arlington, Virginia: Orzechowski and Walker, 2003

- 20.Aguinaga Bialous S, Glantz S A. Arizona's tobacco control initiative illustrates the need for continuing oversight by tobacco control advocates. Tob Control 19998141–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiilamo H. Tobacco industry strategy to undermine tobacco control in Finland. Tob Control 200312414–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novotny T E, Siegel M B. California's tobacco control saga. Health Aff 19961558–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trochim W M K, Stillman F A, Clark P I.et al Development of a model of the tobacco industry's interference with tobacco control programs. Tob Control 200312140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsoukalas T H, Glantz S A. Development and destruction of the first state funded anti‐smoking campaign in the USA. Tob Control 200312241–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luke D A, Krauss M. Where there's smoke there's money: tobacco industry campaign contributions and U.S. congressional voting. Am J Prev Med 200427363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saffer H, Chaloupka F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. Journal of Health Economics 2000191117–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierce J P, Gilpin E A. How did the Master Settlement Agreement change tobacco industry expenditures for cigarette advertising and promotions? Health Promot Pract 20045(3 suppl)84S–90S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keeler T E, Hu T ‐ W, Ong M.et al The US national tobacco settlement: the effects of advertising and price changes on cigarette consumption. Applied Economics 2004361623–1629. [Google Scholar]