Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the impact and relevance of the national awareness day “No Smoking Day” 22 years after it was launched.

Design

Triangulation of data from a variety of sources. Retrospective surveys conducted one week and three months after No Smoking Day, media coverage, website activity, and volume of calls to national smokers' helplines.

Main outcome measures

Self reports of awareness and smoking behaviour changes one week and three months after No Smoking Day. Volume of media coverage, visits to No Smoking Day website, and volumes of calls to smokers' helplines.

Results

Follow up at one week indicates awareness of No Smoking Day is lower in 2004 than in 1986 but still high at 70% for all smokers. The decline in participation from 18% of aware smokers in 1994 to 7% in 2001 has been reversed and in 2005 19% quit or reduced their smoking on No Smoking Day. Three months after No Smoking Day awareness was 78% in 2004, lower than in previous studies but still high and equivalent to 9 965 000 smokers when applied to the population estimate of UK smokers. Likewise participation has decreased but at 14% in 2004 is equivalent to an estimated 1 840 000 (1 in 7 of UK smokers) claiming to quit or reduce their consumption on the Day. Among those who participated, 11% were still not smoking more than three months after the Day, equivalent to an estimated 85 000 smokers (0.7% of UK smokers). Media volume has increased even though campaign spend has remained relatively constant and calls to national smokers' helplines on No Smoking Day are typically four times those received on an average day.

Conclusions

These data suggest that after 22 years No Smoking Day continues to be successful in reaching smokers. With a budget insufficient to pay for advertising, this public awareness campaign supported by local activities appears to be effective in helping smokers to stop.

Keywords: No Smoking Day, mass media, impact, helpline, cessation

Until the mid 1990s, No Smoking Day was the leading smoking cessation campaign in the UK. Launched in 1984, the campaign seeks to create a supportive environment for smokers to give up. When the campaign began, smoking prevalence in the UK was more than 33% of adults; in 2003 it was 25%.1 Initially the campaign encouraged smokers to quit just for the Day. By the mid 1990s, emphasis had shifted to encouraging smokers to quit for good.

In the early 1990s No Smoking Day had an annual budget of around £550 000 drawn from various funding organisations and campaign material sales. Campaign expenditure has changed very little at £470 000 in 2004.

With the available budget, paid for advertising is not an option. The campaign does not offer the personal support and encouragement for the individual smoker, but signposts towards existing effective support.

No Smoking Day seeks to attract maximum publicity for smoking and health at minimum cost by creating news stories and events to attract media coverage. A network of organisers supports the campaign at a local level by running events and helping smokers who want to stop smoking. The campaign supports these activities with the provision of materials and training.

The first England‐wide integrated mass media campaign aimed at adult smokers cost just over £3 million and ran on TV for three months between December 1994 and March 1995. Studies show that media campaigns combined with community interventions can be effective in increasing smoking cessation.2,3,4,5,6,7

The first ever government white paper on tobacco, Smoking kills, was published in 1988.8 This promised £100 million over three years for tobacco control in England, including up to £60 million to establish smoking cessation services in the National Health Service. In 2000–1 the number of successful quitters using the services at four week follow up was 119 800, and by 2003–4 this number had risen to 204 900.9 In 2000, the first year of the Department of Health led mass media campaign, £6.18 million was spent on TV advertising. By 2004 this figure had increased threefold to £19.36 million.

Following the publication of the tobacco white paper a number of other government papers have highlighted the need to tackle tobacco.10,11 The Acheson (1990) and Wanless (2004) reports identified the reduction of smoking prevalence as one of the major strategies for reducing health inequalities.12,13 The 2004 white paper Choosing health sets out a number of strategies for tackling tobacco including reducing exposure to second hand smoke, increased promotion of the stop smoking services, and better access to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).14

The purpose of this paper is to summarise some of the key measures that have been used to evaluate the impact of No Smoking Day and to consider whether the campaign is as relevant now as it was when launched 22 years ago. Public awareness days about smoking now occur across the world and are seen as cost effective public health interventions.15,16

METHOD

A randomised control trial is not appropriate for a national awareness campaign, particularly one that has been running for 22 years. There can be no random allocation of individuals to experimental and control groups. Even if allocations could be made using more naturalistic units such as workplace settings or TV regions, it would be difficult to avoid contamination of the comparison units. More appropriate is the accumulation of data from a variety of sources and research. If they all point in the same direction it is reasonable to assume that the programme has been successful.17 This technique, known as triangulation, is recognised for providing evidence and is the method adopted to evaluate the aims and impact of the No Smoking Day campaign.

Annual tracking study

Awareness of and participation in No Smoking Day is monitored through an annual tracking survey. The questionnaire has remained constant since 1986 to allow year on year comparisons. Awareness is measured by asking respondents the question: “Did you know that Wednesday xx was No Smoking Day?” Participation is measured by asking respondents who smoke the question: “Did you stop or try to stop smoking on No Smoking Day?” Participation, therefore, includes smokers who tried to stop on the Day but failed and smokers who cut down on the Day as well as smokers who successfully stopped for the whole Day or longer.

Between 1986 and 1998 the questions were placed on a random omnibus survey designed to be representative of all adults aged 16 or over in Great Britain. As many as four recalls were made to contact respondents and no substitutes were taken. From 1999 onwards, the questions were placed on a survey using random location sampling. It too was designed to be representative of all adults in Great Britain. In these surveys, 2000 respondents are selected according to a random location method, with sampling points selected by probabilistic methods, and individuals in each sampling point selected by quota. Quotas are set in terms of age and sex within working status.

The fieldwork usually takes place about one week after the Day with around 1800 interviews conducted in the respondents' own homes.

Three month follow up studies

The purpose of these surveys is to assess the impact of No Smoking Day in the longer term. Although the methodology has remained constant to allow comparison between surveys, the surveys have differed in sample size due to variations in the budget available for research.

The 2004 study involved face‐to‐face interviews, conducted by NOP Social and Political, with a quota sample of 4928 smokers and recent ex‐smokers aged 16 and over in 137 parliamentary constituencies across the UK between 13 and 30 June 2004. In each parliamentary seat, interviewing was conducted in two separate areas to reduce the possible impact of clustering on the estimated sampling error. An average of 36 interviews was obtained from each constituency. All interviews were carried out in‐street using the “next person passing” principle to avoid focusing on obvious smokers. Potential respondents were screened to check for eligibility—that is, whether they met the demographic quotas and whether they were either a current smoker or had given up since the beginning of March 2004. Quotas were set for sex, four age groups, and three social classes (ABC1/C2/DE). In the AB group the head of household occupies higher or intermediate managerial, administrative or professional jobs. The head of household in the C1 group occupies a non‐manual occupation, typically supervisory, clerical or junior managerial, administrative or professional. The C2 group comprises skilled manual workers, while the DE group consists of semi‐ and unskilled manual workers, state pensioners, widows (with no other earner), and casual workers. The demographic profile was generated from the General Household Survey and from a National Opinion Poll (NOP) survey for No Smoking Day at the time of the event in March 2004. (The results have been weighted to ensure that the demographic profile of the sample reflects that of all smokers in March 2004.)

These long term surveys are also used to estimate the population impact of No Smoking Day. Estimates of the adult population from the Office of National Statistics are combined with the corresponding estimates of smoking prevalence taken from the General Household Survey to produce estimates of the total number of adults who smoke.1

Media evaluation

The media impact of the campaign is measured using the total volume of coverage and the advertising value equivalent.

Throughout the campaign period all national UK print media is tracked for mentions of No Smoking Day. The tracking period runs from December until April. All print publications are read for any editorial mention of No Smoking Day. Advertising campaigns mentioning No Smoking Day are excluded from the tracking process.

Articles that include a mention of No Smoking Day are classified as a single story. The total number of stories mentioning No Smoking Day is the total volume of coverage. These figures are absolute and represent all media mentions.

The advertising value equivalent demonstrates the value of media coverage in monetary terms. It is calculated by considering the “page rate” of publications that feature a No Smoking Day story. The page rate is the cost of buying a full page advertisement in the publication, on the page that the story has appeared. A page rate for an advertisement on page 7 would be less than for page 1. The advertising value equivalent of the story is based upon the proportion of the page that is taken up by the No Smoking Day story. If the story covered 25% of the page, then the advertising value equivalent for the story would be 25% of the page rate.

The net public relations spend for No Smoking Day is based upon the year end figure for direct expenditure on media related activities by No Smoking Day. The net campaign expenditure is the year end figure for all campaign costs incurred by No Smoking Day. This relates only to campaign costs and does not include indirect costs such as staff and premises.

Web tracking

The numbers of visitors to the No Smoking Day website are tracked electronically. The numbers of unique visitors are counted. Unique visitors are determined by cookies to be first time or returning visitors and are counted once in a report period. As the website is a relatively new addition to the campaign, set up in 2000, in depth data for reporting has only been available for two years.

Calls to helplines

As part of the national mass media campaigns smokers are encouraged, particularly through TV advertising, to telephone a helpline. Between 1995 and 1999 the main helpline provider was Quitline.18 Staffed by trained counsellors, Quitline provides help and support to smokers who want to stop smoking. From 2000 onwards the main provider has been the National Health Service (NHS) helpline. It gives help and advice to smokers to quit and information on local NHS cessation services. Although a variety of features of call activity are monitored, this paper focuses on the total number of calls received. Independent data on call volumes are provided by the service providers for the helplines such as British Telecom.

RESULTS

Percentages were rounded for awareness and participation for both the annual tracking surveys and the three month follow up studies.

Annual tracking study: 1986–2005

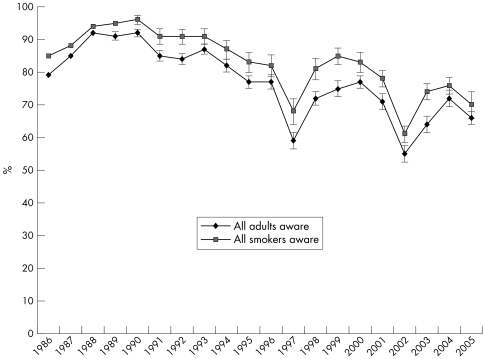

Figure 1 shows prompted awareness of the campaign among all adults and smokers. 1990 witnessed the highest level of awareness with 92% for adults and 96% for smokers. Since then awareness gradually declined reaching the lowest recorded levels in 1997 (59% and 68% of all adults and all smokers, respectively) and 2002 (55% and 61% of adults and smokers, respectively). However, in each case, the significant dip has been followed by a steady increase. In 2005 awareness was 66% for adults and 70% for smokers.

Figure 1 Awareness of No Smoking Day 1986–2005.

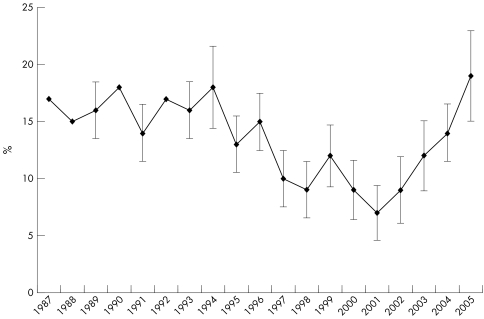

Participation is defined as anyone who stops or tries to stop smoking on the Day. Between 1987 and 1996 participation among smokers aware of No Smoking Day fluctuated between 13–18% (fig 2). The highest recorded level of 18% was achieved in 1990 and 1994 and the lowest level of 7% was recorded in 2001. Since 2001 the decline has been reversed and in 2005 the percentage participating in the campaign was not significantly different to the highest level previously recorded.

Figure 2 Percentage of smokers aware of No Smoking Day participating in the Day 1987‐2005.

Three month follow up studies: 1986, 1989, 1992, 1996, 2004

In the 2004 study overall awareness for No Smoking Day was 78%, slightly down on 1996 when 83% were aware of the Day and lower still than the remaining three studies conducted in 1992, 1989, and 1986. The highest recorded level was in 1986 when 89% were aware of the Day (table 1).

Table 1 Summary of awareness, smoking and participation for three month follow up studies 1986–2004.

| Survey base: all smokers | Year of survey | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 1989 | 1992 | 1996 | 2004 | |

| n = 6178 | n = 10133 | n = 6002 | n = 5061 | n = 4928 | |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Aware of No Smoking Day | 89.0 (0.8) | 86.0 (0.7) | 86.0 (0.9) | 83.0 (1.3) | 78.0 (1.2) |

| Attempted to reduce or stop smoking on No Smoking Day | 18.0 | 18.0 | 20.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Gave up or cut down on No Smoking Day | – | – | 18.0 (0.7) | 14.0 (1.2) | 14.0 (1.0) |

| Gave up or cut down for 1 day or less | 11.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 |

| Gave up or cut down for >1 day <3 months | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| Gave up or cut down for 3 months | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | |

| Gave up for three months | 0.5 (0.18) | 0.5 (0.19) | 0.3 (0.18) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.3) |

| Smokeless for 3 months | 2.3 (0.37) | 2.7 (0.44) | 2.8 (0.47) | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.3) |

All of those who were interviewed were asked if they had attempted to give up or cut down their smoking on No Smoking Day. Fifteen per cent reported that they had done so, the same as in 1996 but lower than in 1992, 1989, and 1986 (table 1).

Table 2 shows attempted participation among several subgroups in the 2004 survey. The highest levels of participation were recorded for the lightest and youngest smokers (both 21%). Light consumption is defined as smoking up to 10 cigarettes a day, medium consumption 11–20 cigarettes a day, and heavy consumption 21 or more cigarettes a day. Participation was similar for men and women (14.9% and 16.5% male and female, respectively) and across social groups (15.4% for group AB; 15.3% for group C1; 16.1% for group C2; and 15.7% for group DE).

Table 2 Attempted participation in No Smoking Day.

| Total | Heavy* | Medium* | Light* | 16–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Yes | 15 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 21 | 17 | 14 | 11 | 13 |

| No | 83 | 90 | 86 | 77 | 77 | 82 | 85 | 88 | 85 |

| Do not know or not stated | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

*Light consumption is defined as smoking up to 10 cigarettes a day, medium consumption 11–20 cigarettes a day, and heavy consumption 21 or more cigarettes a day.

Base: all = 4928.

Respondents who attempted to give up or cut down were then asked what they actually managed to achieve on the Day. A very high proportion reported that they had managed to either stop smoking for all or part of the Day or cut down on the number of cigarettes they smoked on the Day. This finding was common throughout the series of surveys (table 1).

The situation three months after No Smoking Day

All respondents who had successfully participated in No Smoking Day were asked how long they had managed to stop or reduce their smoking. In the 2004 study, after excluding “don't know” and “missing” from the number of successful participants, 50% (311/624) said they continued the positive change beyond 10 March.

Focusing only on those who participated in No Smoking Day 2004 by stopping smoking, the vast majority (333/422 = 79%) relapsed within one month. Nevertheless, around one in 10 (45/422 = 11%) were still not smoking more than three months after the Day itself.

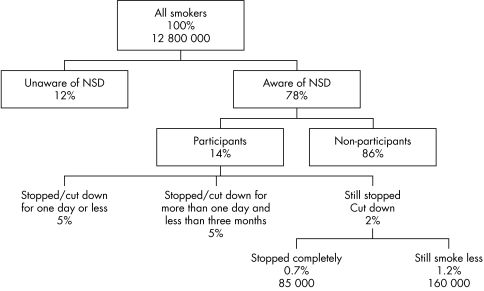

The estimated population impact of No Smoking Day 2004 is shown in fig 3. Based on a total population of 12 800 000 smokers and an awareness of 78% (95% confidence interval (CI) 72.8% to 79.2%), an estimated 9 965 000 of smokers were aware of the Day (95% CI 9.82 to 10.11 million). Participation of 14% (95% CI 13% to 15%) yields an estimated 1 840 000 of smokers who actively took part in the Day by stopping smoking or cutting down their consumption on the Day (95% CI 1.72 to 1.97 million). More than three months after the Day an estimated 85 000 (0.7%, 95% CI 0.4% to 1.0%) of smokers were still not smoking (95% CI, 55 000 to 115 000) and an estimated 160 000 (1.2%, 95% CI 0.9% to 1.5%) of smokers had cut down their consumption (95% CI 120 000 to 200 000).

Figure 3 Changes in smoking habits on and three months after No Smoking Day (NSD) 2004. Base: all UK smokers, General Household Survey (GHS) 2004.

Media evaluation

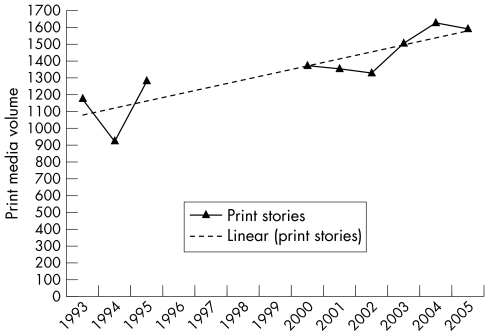

Figure 4 shows the net print media stories featuring No Smoking Day among all UK print media. The lowest volume of media coverage was 934 stories in 1994. Records of media volumes are not available for 1995–9 as the methodology for measuring media impact during this period used net word count as an indicator rather than net volume of stories as shown in fig 4. Although there was a small reduction in the volumes of media coverage from 1378 stories in 2000 to 1334 stories in 2002, the period from 2002–4 has experienced a large increase in media volume to the highest ever volume of 1633 in 2004 (fig 4).

Figure 4 Volume of media stories featuring No Smoking Day.

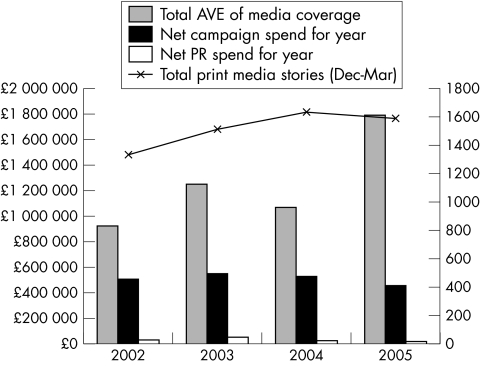

The advertising value equivalent (AVE) of media stories relating to No Smoking Day has been tracked from 2002 to 2005 (fig 5). The lowest figure was in 2002 when the AVE was £926 026. Since 2002 the figure has exceeded £1 million, peaking at £1 252 813 in 2003. Figure 5 presents the value of the media coverage against the total campaign and public relations expenditure of the No Smoking Day charity. This total campaign spend for No Smoking Day has remained broadly consistent over the last three years at around £500 000. The total public relations spend for the campaign generally constitutes about 10% of total campaign expenditure (fig 5).

Figure 5 Volume and costs of media coverage. £1 is currently equivalent to around €1.4 and $1.7. AVE, advertising value equivalent.

Web tracking

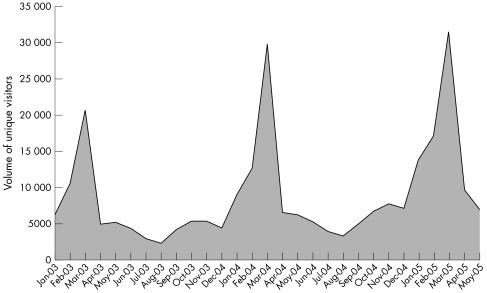

For the period reported, the average number of monthly unique visitors to the No Smoking Day website is 8970. No Smoking Day is held annually in March; in the period building up to the campaign the number of visitors to the site increases significantly. In March 2003 the number of unique visitors was 20 729, and by March 2005 it reached 31 485 (fig 6).

Figure 6 Unique visitors by month.

Calls to helplines

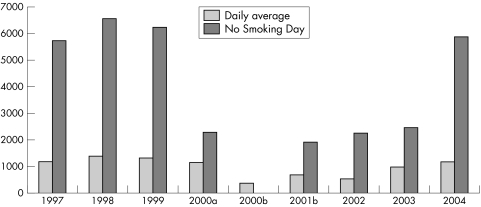

The total number of calls to the national helpline for smokers on No Smoking Day and the annual daily average are shown in fig 7. Without exception, each year shows a substantial increase in the number of calls taken on No Smoking Day compared with the daily average. The 4.8 times average increase observed in 1998 and 1999 was exceeded in 2004 when the number of calls received on the day was more than five times the daily average for that year.

Figure 7 Calls to national telephone helpline for smokers. 2000a: No TV advertising of Quitline, Broadsystems commissioned by Department of Health. 2000b: Broadsystems took over from Quitline on 1 June 2000. Full data incomplete and average figures based on 214 days. 2004: Based on 246 days. Average calls likely to decline when data from remainder of year included. 1996: On No Smoking Day Quitline received 27 121 calls after switching to a freephone number in Nov 1995 and being featured in TV advertising.

DISCUSSION

Annual tracking 1986–2005

The No Smoking Day campaign has consistently reached high levels of public awareness among the general population and adult smokers. In the early days of the campaign the concept of a “national awareness day” orientated around a campaign was relatively new, and No Smoking Day was one of a handful of campaigns. Now there are more than 600 awareness campaigns in the UK.19 Although there has been a gradual decline since 1990 in the levels of awareness of No Smoking Day for both the population and adult smokers, the Day is now operating in a far more competitive and crowded public relations market. In this context the current levels of awareness are still very high.

There are two significant dips in awareness of the campaign. The first occurred in 1997 when the campaign period coincided with the build up to the general election. The second occurred in 2002 when for the first time in a number of years an external communications agency was not used to promote the campaign. The loss of key staff during the build up to the campaign may also have contributed to a less successful year.

Between 1994 and 2001 No Smoking Day experienced a gradual decline in participation and UK smoking prevalence remained stable. From 2001 smoker participation in No Smoking Day has increased year on year and UK smoking prevalence has declined by around 0.4% per year.1,20 Concurrently, the UK government introduced major initiatives aimed at encouraging smokers to stop. This suggests that rather than competing, the various campaigns work in synergy and in so doing have contributed to reversing the plateau in smoking prevalence that prevailed in the mid to late 1990s.

The network of tobacco control alliances supported by No Smoking Day plays a key role in promoting the Day at the local level. In addition to helping smokers who want to stop, the events run by the alliances contribute to the mass of unpaid media coverage achieved around the Day. The importance of combining mass media campaigns with community led activities has been highlighted in many studies.3,4,5,6,7 However, most of these studies utilised paid‐for advertising. The results of this study suggest that unpaid media campaigns can also be effective. A recent study of the cost effectiveness of smoking cessation programmes suggests that No Smoking Day is highly cost effective (cost £26 per life year saved, £40 when discounted).15

In the 2004 three month follow up study participation in the Day was highest with smokers in the 16–24 year age bracket and light smokers (⩽ 10 cigarettes per day). Data from the 2002 General Household Survey shows that the lightest smokers (⩽ 9 cigarettes per day) and smokers aged 16–24 are least likely to have made a quit attempt in the previous year. It would appear that No Smoking Day is making a strong impact on these smokers, and encouraging people to stop early in their smoking career when the maximum health benefit can be gained, and life years reclaimed.1,20

Three month follow up surveys for the years 1986, 1989, 1992, 1996, 2004

The three month follow up surveys assess the sustainability of attempts to stop or cut down. Focusing on the most recent survey, an estimated 14% of UK smokers gave up or cut down. At the population level this represents around 1.8 million UK smokers (1.72–1.97 million). While this demonstrates that smokers are engaging with the Day, the current objective of the organisation is to act as an opportunity to stop, and to stay stopped. In 2004 an estimated 85 000 smokers (55 000–115 000) who had stopped on the Day were still not smoking three months later. These figures compare favourably with the previous follow up studies and are a significant achievement given that the absolute number of smokers in the population has been steadily declining (13.7 million in 1992 to 12.8 million in 2003).21

Other indicators

There has been huge investment in recent years in support services for smokers who want to stop, and No Smoking Day has strategically aimed to drive smokers towards using help rather than trying to stop alone.

What this paper adds

This study suggests that unpaid media campaigns, supported by local activity, can be effective in helping smokers to stop. It also suggests that such campaigns can be effective over a significant number of years despite the introduction of other related campaigns and an increasingly crowded media relations market.

The impact of No Smoking Day on the take up of services to help smokers is evident where recorded. The NHS stop smoking services record the number of smokers using them on a quarterly basis so it is not possible to see the direct impact, although the January to March quarter that includes No Smoking Day has by far the highest number of participants.

As help line call volumes are recorded on a daily basis, the call volumes for the Day can be isolated and compared to daily averages. Since 1997, the number of calls on No Smoking Day to the national helpline has averaged four times the daily average. The greatest impact of No Smoking Day on call volumes can be seen before 2000 and in 2004. In the period 1997–9 the helpline was a major source of help to smokers who wanted to talk to a health professional about stopping. During this time the helpline was operated by the charity Quit and callers spoke to a trained councillor. In 2000 the NHS sponsored helpline was re‐contracted to a call centre company and became a referral service for local stop smoking services. This led to a dip in call volumes as a new advertising campaign was set up to promote the new number. This affected call volumes on No Smoking Day. By 2004 the call volumes were reaching the pre‐2000 levels.

The study has a number of limitations. The one week follow up data survey is conducted through NOP omnibus surveys relying upon methodology used by the market research organisation. In 1999 the organisation changed its methodology from a random omnibus survey to a random location survey. The yearly questionnaire changed in 1998, before reverting in 2004 to its original format. This means that there is not complete trend data for the full 20 years. The gap in the media data is down to changing methodologies in measuring coverage by media monitoring firms used since 1993. Evaluations look at the impact of No Smoking Day retrospectively, unlike some measures of awareness that utilise “pre” and “post” measures. It is difficult to isolate the impact of No Smoking Day from other contemporaneous interventions. However, the strength of the No Smoking Day brand in March appears established enough to act as a major catalyst for increased marketing and promotional activity from commercial and public health interests in smoking cessation.

Lack of biochemical validation is another concern. Several studies have documented that self reported smoking status leads to an overestimate of successful quit attempts.22,23,24

Despite the limitations described above, the varieties of indicators provide converging evidence of the impact of No Smoking Day. In particular, they show that the Day encourages and helps smokers to stop.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from Cancer Research UK and the Department of Health. The authors would like to thank Richard Glendinning from NOP and the staff and trustees of No Smoking Day.

Footnotes

Competing interest: This research was part funded by the No Smoking Day charity. All data was collated by independent market research agencies, and from independent audits of public services. Lesley Owen is a trustee of the No Smoking Day charity and Ben Youdan is the Chief Executive of No Smoking Day.

References

- 1.Office of National Statistics General Household Survey 2003; mid‐2003 population estimates: Great Britain. ONS 2004

- 2.Grey A, Owen L, Bolling K.A breath of fresh air: tackling smoking through the media. London: HAD, 2000

- 3.Naidoo B, Warm D, Quigley R.et al Smoking and public health; a review of reviews of interventions to increase smoking cessation, reduce smoking initiation and prevent further uptake of smoking. HAD 2004

- 4.Levy D T, Friend K. A computer simulation model of mass media interventions directed at tobacco use. Prev Med 200132284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman L K, Glantz S A. Evaluation of anti‐smoking advertising campaigns. JAMA 1998279772–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierce J P, Macaskill P, Hill D. Long‐term effectiveness of mass media led antismoking campaigns in Australia. Am J Public Health 199080565–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McVey D, Stapleton J. Can anti‐smoking television advertising and local tobacco control activity affect smoking behaviour? A controlled trial of the Health Education Authority's anti‐smoking campaign. Tob Control 20009273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anon Smoking kills; a white paper on tobacco. London: HMSO, 1998

- 9.Office of National Statistics Department of Health Statistical Bulletin: Statistics on smoking cessation services in England, April 2003 to March 2004. ONS 2004

- 10.Department of Health Coronary heart disease: national service framework for coronary heart disease. London: DoH, 2000

- 11.Department of Health The NHS cancer plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: DoH, 2000

- 12.Acheson D.Independent inquiry into inequalities in health. London: HMSO, 1998

- 13.Wanless D.Securing good health for the whole population. London: HM Treasury, 2004

- 14.Anon Choosing health: making healthier choices easier. Public Health White Paper. London: HMSO, 2004

- 15.Parrott S, Godfrey C. Economics of smoking cessation. BMJ 2004328947–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Przewoźniak K. Participation action for a great European Smoke Out. ENSP 2004

- 17.Tones K. Beyond the randomized controlled trial: a case for ‘judicial review'. Health Educ Res 199712I–IV, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen L, Lafferty G. Quitline, An audit of the national helpline for smokers 1995–1998. HEA 2000

- 19.UK Awareness Campaign Register The Profile Group 2005

- 20.Jarvis, M Monitoring cigarette smoking prevalence in Britain in a timely fashion. Addiction 2003981569–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lader D, Meltzer H.Smoking behavior and attitudes 2002. ONS 2003

- 22.Ossip‐Klein D J, Giovino G A, Megahed N.et al Effects of a smokers hotline: results from a 10‐county self‐help trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 199159325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd N R, Windsor R A, Perkins L L.et al Quality of measurement of smoking status by self‐report and saliva cotinine among pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health 1998277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray R P, Connett J E, Istvan J A.et al Relations of cotinine and carbon monoxide to self‐reported smoking in a cohort of smokers and ex‐smokers followed over 5 years. Nicotine Tob Res 20024287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]