Abstract

Objectives

To test associations between individual health outcomes and ecological variables proposed in causal models of relations between income inequality and health.

Design

Regression analysis of a large, nationally representative dataset, linked to US census and other county and state level sources of data on ecological covariates. The regressions control for individual economic and demographic covariates as well as relevant potential ecological confounders.

Setting

The US population in the year 2000.

Participants

4817 US adults about age 40, representative of the US population.

Main outcome measures

Two outcomes were studied: self reported general health status, dichotomised as “fair” or “poor” compared with “excellent”, “very good”, or “good”, and depression as measured by a score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression instrument >16.

Results

State generosity was significantly associated with a reduced odds of reporting poor general health (OR 0.84, 95%CI: 0.71 to 0.99), and the county unemployment rate with reduced odds of reporting depression (OR 0.91, 95%CI: 0.84 to 0.97). The measure of income inequality is a significant risk factor for reporting poor general health (OR 1.98, CI: 1.08 to 3.62), controlling for all ecological and individual covariates. In stratified models, the index of social capital is associated with reduced odds of reporting poor general health among black people and Hispanics (OR 0.40, CI: 0.18 to 0.90), but not significant among white people. The inequality measure is significantly associated with reporting poor general health among white people (OR 2.60, CI: 1.22 to 5.56) but not black people and Hispanics.

Conclusions

The effect of income inequality on health may work through the influence of invidious social comparisons (particularly among white subjects) and (among black subjects and Latinos) through a reduction in social capital. Researchers may find it fruitful to recognise the cultural specificity of any such effects.

Keywords: social determinants of health, income inequality, depression

There has been a rich efflorescence of research in the past 10 years on the effects of local area income inequality upon health outcomes. It would be fair to say that the literature has bloomed organically, rather than following an orthodox scientific path. The literature germinated with the finding of a stylised fact in ecological data,1 but has matured over the years.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24

The work on causal pathways through which income inequality might influence health outcomes is less well developed, but is clearly an important direction for this literature.5,7,8,14,23,25,26,27 This paper tests associations between county level income inequality, the proposed mediators, and individual level health outcomes.

Conceptual model

Kawachi and Kennedy (1999) summarised three mechanisms through which high levels of income inequality could adversely affect health status28,29,30:

High levels of income inequality reduce social capital, which then leads to poor individual and community health;

High levels of income inequality lead the rich to withdraw support for public services, leading to a decline in individual and community health29,31;

High levels of income inequality increase the opportunity for invidious comparisons, which increase people's stress levels, leading to a decline in their individual and therefore the community's health.32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40

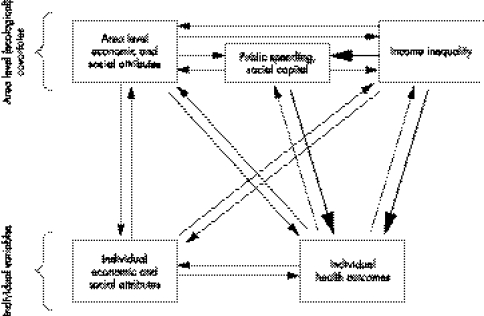

These mechanisms continue to be plausible, but more work remains to be done to empirically test such effects. Figure 1 presents a conceptual model of these pathways.

Figure 1 Conceptual model of the links between income inequality and health, with individual and ecological confounders. The thick arrows represent potential causal pathways between income inequality and health outcomes previously proposed in the literature. The thin arrows represent possible confounders to these relations. Downward arrows represent the effects of area level covariates on individual outcomes; upward arrows represent aggregation effects.

The thick arrows represent the proposed causal pathways between income inequality and health outcomes. The effect of invidious comparisons is represented by a direct arrow from income inequality to health outcomes. The other proposed causal pathways are mediated by the public spending and social capital. The thinner arrows represent other possible or known causal relationships. On the top of the model are variables that are defined at the local level (ecological variables). These include income inequality, public spending, and social capital, as well as other features of the social and economic environment, such as racial/ethnic makeup, unemployment and crime rates, average incomes, and the cost of living. On the bottom are variables defined at the individual level, including health outcomes, but also individual social and economic attributes.

Downward arrows represent the effects of place on individual attributes and on health. Examples include the observation that local spending on public health can have a positive impact on individual health outcomes,41 that a wealthier community offers more economic opportunities to raise individual income, or that a higher crime rate can lead to worse individual health outcomes, for example through interpersonal violence. Upward arrows reflect the influences of aggregation effects of selection. For example, economic migrants tend to be healthier than non‐migrants, and generally target wealthier communities as migration destinations to take advantage of better economic opportunities. The result is a selection process that reallocates comparatively healthier people to comparatively wealthier communities. Or consider the example of a small community to which a nursing home or a prison is introduced. Inequality will increase and average individual health will decrease, as these persons in institutions tend to be both less wealthy and less healthy than those in the general population.

This conceptual model visually represents several constraints in this literature that pertain not just to testing associations along the proposed causal pathway, but to any analysis of income inequality and health generally. It has previously been argued that the association between income inequality and health could be confounded by area level racial/ethnic makeup.4,42 Similarly, several other local social or economic attributes are likely to significantly confound such a relation43,44:

Education

Many of the potential confounding relations arise because public spending is correlated across categories. Education is an example: public spending on education promotes educational attainment and education quality,45,46 and education has been shown in numerous studies to foster good physical and mental health.29,47

Crime

Crime has been shown in several analyses to be sensitive to income inequality.8,26,48,49,50,51,52,53 Crime rates are also sensitive to the amount and type of public spending, and are associated with the level of social capital.54,55,56,57 In turn, high crime can affect individual health both through direct effects on victims and indirectly through the stress of living in high crime areas.58,59

Wages and employment

It has been argued in the economics literature43,60,61,62,63 that a high level of economic inequality may reduce economic growth and efficiency, which could accordingly lead to low wages for unskilled labour and a high level of unemployment. In the mental health literature, it has been abundantly shown that both low wages and unemployment lead to depression.45,64,65,66,67 By contrast, the effect of local area unemployment, controlling for individual employment status, could operate positively or negatively, depending on whether workers see high local unemployment as a threat to their own employment, or as part of a context in which they are happy to have a job or less likely to see their own unemployment as a personal failure.

Cost of living

What economists call pecuniary externalities arise because as people at the top of the income ladder become wealthier they frequently use part of their additional wealth to invest in land and housing, thereby bidding up the cost of living for everyone. Those who do not see their incomes expand may experience a reduction in their real income, which in turns leads both to stress and also to tighter budget constraints that force difficult choices among health promoting expenditures.

Racial/ethnic effect modification

There are sound theoretical and empirical reasons for believing that the causal mechanisms articulated by Kawachi and Kennedy will work differently for those in different racial/ethnic groups. A rich literature in social psychology has established that while in general upward social comparisons are damaging to self esteem,68 for members of disadvantaged minority groups (black people and Latinos), within‐group upward social comparison can also be enhancing for self esteem because it counteracts negative stereotypes about the group.69,70 Minority members' social comparisons with non‐minorities have a much smaller, or even zero, effect.69,71 This literature has found no such effect for Asian‐Americans, with the proposed explanation that they are not underprivileged minorities.50

The effects of social capital, being inherently socially constructed, are particularly likely to be specific to racial/ethnic groups.52,63,72 Patterns of social capital have been shown to differ by race/ethnicity,35 as have the effects of social capital on children's behavioural problems.52

The effects of public spending may also be different for minorities than for non‐minorities, because the safety net may be more important for minorities—who have fewer financial assets73,74 and suffer more discrimination in hiring75—than for white people with equivalent incomes or education.

The rationale for such effect modification has to date largely been structured around minorities' outsider or inferior status, rather than around any specific cultural features. As such, one might expect these relations to be similar among disadvantaged minority groups (that is, black people and Latinos), with little effect modification within minorities (that is, black people compared with Latinos). This proposition remains an empirical question.

Methods

Data

The individual level data for this analysis come from the year 2000 wave of the national longitudinal survey of youth (NLSY), a nationally representative sample of adults in the USA in their early 40s, not counting recent immigrants.76 Attrition has been low overall and evenly distributed across relevant sub‐groups.77 Follow up rates for the NLSY range from 85%–90% by the late 1990s.77 As a result, the analysis sample is highly representative for the relevant US population.

Complete data were available for 4817 people, as described in table 1. The mean age was 42.1 years, with a range from 40–45. Black people and Latinos were over‐sampled to permit valid inferences about these two important subgroups, and population weights are available. Ecological variables were gathered from a variety of sources described below, and were linked to individual records using the person's county of residence.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics (4817 observations).

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Poor health | 12.2% | |

| Depressed | 11.6% | |

| Hypothesised ecological causal variables | ||

| State social capital index | −0.24 | 0.20 |

| State generosity | −0.01 | 1.00 |

| Local income inequality | ||

| County log per cent rich | 1.95 | 0.63 |

| Ecological confounders | ||

| County log unskilled wage | 9.51 | 0.25 |

| County/state housing affordability index | 69.69 | 13.68 |

| County crime rate | 4.31 | 2.16 |

| County unemployment rate | 4.45 | 2.74 |

| County log per cent black | −2.62 | 1.46 |

| County log per cent Hispanic | −2.87 | 1.34 |

| County log mean income | 10.81 | 0.28 |

| County log mean years of education | 12.93 | 0.80 |

| County psych services index | −0.06 | 0.63 |

| County health services index | 1.63 | 0.17 |

Dependent variables

Self reported physical health is assessed in a question in which respondents were asked “In general, would you say your health is…” and then given a five item response list from excellent to poor. The lowest two items, fair and poor, were then combined to create a dichotomised indicator of poor physical health status.

Depression is measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CES‐D).78,79,80,81,82,83 Consistent with prior literature, the scale was dichotomised at 16 as a cut off score for depression status.81,84,85,86

Main predictors

Income inequality

The measure of income inequality used was the county level percentage of households with income over $150 000 annually (“the per cent rich”). As the county level average income was separately controlled, the percentage of population earning over this threshold serves as a measure of income inequality.

There are conceptual differences between this measure of inequality and that used in many previous studies, the Gini coefficient. The Gini coefficient is sensitive to inequality among the very rich. By contrast, the percentage of county households that earn over $150 000 annually yields a measure for how often people of moderate means might interact with someone who earns a great deal of money. As such, the measure of inequality used is close to the measures of polarisation, recently proposed in the economics literature.87,88 To fix ideas, consider what happens when Bill Gates doubles his income: the Gini coefficient increases, potentially dramatically, while the percentage of the county with incomes over $150 000 does not. We would argue that the per cent rich more accurately reflects the kind of inequality that might play a part in health outcomes.42,51,89

Social capital

Measures of social capital were taken from the general social survey (GSS) conducted by the National Opinion Research Center. In all, we included nine GSS measures capturing civic engagement (the number of per capita groups to which respondents belonged), social trust (most people are fair; look out for themselves; are helpful; can be trusted; the government should do more), and three measures of anomia (the lot of the average man is getting worse; not fair to bring a child into world; officials are not interested in average man).

The GSS reflects a nationally representative sample of non‐institutionalised, English speaking US residents who are at least 18 years of age. Data from survey years 1984–1998 were averaged for 22 537 individual respondents living in 143 GSS primary sampling units (PSUs) covering 45 states. The GSS estimates were adjusted using post‐stratification weights to reflect the composition of the population at the state and county level using methods described elsewhere.33,37 Where county social capital variables were not available, they were imputed with their state level values.

We performed psychometric analyses and variable reduction by factor analysis to arrive at a single, robust overall measure of social capital, measured at the state level.33 The factor analysis showed one factor with an eigenvalue of 3.5, and no other factors with eigenvalues >1. Loadings were high on seven of the nine GSS variables, and low on the other two. Accordingly, we constructed a simplified scale in which these seven items were summed without weighting. Cronbach's α for this scale was 0.82. The seven items were: “most people are fair”; “…can be trusted”; “…are helpful”; “government helps people” as well as the three measures of anomia. Results were not substantively different when using the county level compared with the state level social capital variables, so the state level social capital variables were retained.

Generosity of state spending

Generosity of state spending was measured as the financial standard (or dollar amount) for a family of family of four receiving benefits under Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) in 1995, as reported in the Urban Institute's Welfare Rules database.90 We use data from 1995 rather than more recent data because the welfare reform act of 1996 greatly proscribed states' latitude in setting welfare payments.

Invidious comparisons

It is difficult to find an ecological variable that serves as a proxy for the opportunity for invidious social comparisons. The role of invidious comparisons might be seen in the residual effect of income inequality after all other plausible ecological variables (and ecological confounds) have been controlled. To this end, we used the income inequality variable (per cent rich, discussed above) as a proxy for the opportunity for invidious comparisons with all other ecological variables controlled. At the same time, we note that this variable might be proxying for other phenomena, and that any results for this variable will have to be interpreted with caution.

Ecological confounders

Affordability

Local affordability was measured using the first quarter 2002 housing opportunity index (HOI), compiled by the National Association of Home Builders and Wells Fargo Bank, defined as the share of homes sold in that area that would have been affordable to a family earning the median income.91

Crime

The 1999 county level crime rate was measured as the number of serious crimes known to police in 1999 per 1000 population, as recorded in the US Census County and City Data Book, 2000 edition.92

Unskilled wages

Data describing county level average annual wages for people employed in the household services sector in 2000 were obtained from the BLS Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, a quarterly count of employment and wages reported by employers and covering 98% of US jobs.93

Unemployment

County level unemployment was measured as the proportion unemployed adults in the civilian labour force using data from the 2000 US census.

Other ecological confounders

We included controls for several other ecological variables that have been shown to correlate with health status, and that may confound the relations studied. These include the county proportion of residents who are black or Hispanic,4 the county mean income, and the county mean educational level, an index of the availability of psychiatric health services, and an index of the availability of general health services.

Individual level confounders

The analysis also controls for individual household income, and the respondent's sex, race, ethnicity, region of residence, current employment status, years of completed education, whether the respondent had health insurance, and whether they lived alone or with a spouse/partner. Each of these individual level variables has been shown to be associated with physical health or symptoms of depression,4,67,94,95,96 and may confound the relation between the ecological variables and health status.

Statistical analyses

Variable transformation

As appropriate, variables were log‐transformed to achieve distributions closer to normal and to provide a better fit to the data.97

Analyses

We performed logistic regressions of the poor physical health indicator and the CES‐D depression indicator on the ecological predictor variables of interest, controlling for individual variables and the ecological confounders. We used the Huber‐White estimator of variance to adjust the standard errors for clustering of individual observations within counties of the NLSY.98 Sample weights were used to make valid inferences for the US population as a whole.

Effect modification

The final model was then tested for effect modification by race/ethnicity. When a Chow test99 showed significant effect modification, stratified analyses were performed.

Results

Tables 1 and 2, respectively, present the descriptive statistics of the data in the sample, and the correlations of the ecological predictor variables.

Table 2 Table of correlations among ecological variables.

| County log per cent black | County log per cent Hispanic | County log mean income | County log mean years of education | State social capital index | State generosity | County psych services index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County log per cent black | 1.00 | ||||||

| County log per cent Hispanic | 0.07 | 1.00 | |||||

| County log mean income | 0.08 | 0.29 | 1.00 | ||||

| County log mean years of education | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.70 | 1.00 | |||

| State social capital index | −0.34 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 1.00 | ||

| State generosity | −0.19 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 1.00 | |

| County psych services index | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 1.00 |

| County health services index | 0.26 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.88 |

| County log unskilled wage | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.33 |

| County/state housing affordability index | 0.05 | −0.48 | −0.24 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.54 | −0.30 |

| County crime rate | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.20 | 0.33 |

| County unemployment rate | −0.07 | 0.24 | −0.48 | −0.66 | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.11 |

| County log per cent rich | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.93 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| County health services index | County log unskilled wage | County/state housing affordability index | County crime rate | County unemployment rate | County log per cent rich | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County health services index | 1.00 | ||||||

| County log unskilled wage | 0.19 | 1.00 | |||||

| County/state housing affordability index | −0.43 | 0.05 | 1.00 | ||||

| County crime rate | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 1.00 | |||

| County unemployment rate | −0.03 | −0.26 | −0.11 | −0.01 | 1.00 | ||

| County log per cent rich | 0.38 | 0.54 | −0.23 | 0.12 | −0.46 | 1.00 | |

Regressions

Table 3 presents regression results for the full sample. Most of the hypothesised ecological causal variables are not significant for either poor health or depression. Exceptions are the index of state generosity, significantly protective against reporting poor health (OR 0.84, CI: 0.71 to 0.99), and the county unemployment rate, significantly protective against reporting depression (OR 0.91, CI: 0.84 to 0.97).

Table 3 Logistic regressions of poor physical health and depression on ecological variables.

| Poor health | Depression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Hypothesised ecological causal variables | ||||

| State social capital index | 1.09 | 0.56, 2.12 | 0.97 | 0.46, 2.03 |

| State generosity | 0.84* | [0.71, 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.86, 1.22 |

| Local income inequality | ||||

| County log per cent rich | 1.98* | 1.08, 3.62 | 0.74 | 0.34, 1.63 |

| Ecological confounders | ||||

| County log unskilled wage | 0.90 | 0.50, 1.61 | 1.20 | 0.63, 2.30 |

| County/state housing affordability index | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.98, 1.01 |

| County crime rate | 1.04 | 0.96, 1.12 | 1.00 | 0.93, 1.07 |

| County unemployment rate | 1.00 | 0.93, 1.06 | 0.91** | 0.84, 0.97 |

| County log per cent black | 1.02 | 0.92, 1.14 | 1.03 | 0.91, 1.15 |

| County log per cent Hispanic | 0.84* | 0.72, 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.80, 1.07 |

| County log mean income | 0.76 | 0.26, 2.24 | 2.83 | 0.69, 11.64 |

| County log mean years of education | 0.59** | 0.42, 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.57, 1.18 |

| County psych services index | 0.93 | 0.60, 1.44 | 1.77* | 1.14, 2.74 |

| County health services index | 1.80 | 0.46, 7.03 | 0.28 | 0.08, 1.04 |

| Number of participants | 4817 | 4817 | ||

| Number of counties | 855 | 855 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.10 | 0.16 | ||

*p<0.05 **p<0.01. Regressions adjusted for individual sex, race/ethnicity, urbanicity, region, income, education, poverty status, employment status, insurance status, and living alone or with spouse/partner.

The measure of income inequality, the county logged percentage of households with income over $150 000 annually is a significant risk factor for reporting poor health (OR 1.98, CI: 1.08 to 3.62), although not depression.

The county's log‐per cent Hispanic is significantly associated with people in those counties reporting poor health (“fair” or “poor”) (OR 0.84, CI: 0.72 to 0.97), but not for depression. The county's log‐per cent black is not significant for either poor health or depression. Income is not significant, but for poor health the county average log‐years of education is highly significant, with a large effect size (OR 0.59, CI: 0.42 to 0.82).

Effect modification

Significant effect modification was identified by race/ethnicity (black and Latino compared with white and Asian‐American—hereafter “white” for simplicity, and to acknowledge that there were few Asian‐Americans in the sample) in both the depression outcome and the poor health outcome. Stratified analyses were accordingly performed for these sub‐samples, and the results are presented in tables 4 and 5. No significant effect modification was identified between Latinos and black people.

Table 4 Logistic regressions of poor physical health on ecological variables, stratified by race/ethnicity.

| Black and Hispanic | White, Asian | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Hypothesised ecological causal variables | ||||

| State social capital index | 0.40* | 0.18, 0.90 | 1.44 | 0.61, 3.44 |

| State generosity | 0.93 | 0.76, 1.13 | 0.83 | 0.67, 1.02 |

| Local income inequality | ||||

| County log per cent rich | 0.73 | 0.32, 1.69 | 2.60* | 1.22, 5.56 |

| Ecological confounders | ||||

| County log unskilled wage | 2.15 | 0.95, 4.88 | 0.71 | 0.36, 1.41 |

| County/state housing affordability index | 1.43 | 0.31, 6.54 | 0.85 | 0.16, 4.62 |

| County crime rate | 1.02 | 0.94, 1.10 | 1.05 | 0.94, 1.17 |

| County unemployment rate | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.06 | 0.99 | 0.89, 1.10 |

| County log per cent black | 0.95 | 0.78, 1.16 | 1.04 | 0.90, 1.19 |

| County log per cent Hispanic | 0.97 | 0.80, 1.18 | 0.80 | 0.67, 0.96 |

| County log mean income | 1.93 | 0.34, 11.07 | 0.66 | 0.20, 2.21 |

| County log mean years of education | 0.94 | 0.67, 1.32 | 0.49** | 0.32, 0.77 |

| County psych services index | 1.13 | 0.72, 1.78 | 0.76 | 0.41, 1.42 |

| County health services index | 0.66 | 0.18, 2.39 | 5.30 | 0.71, 39.30 |

| Number of participants | 2250 | 2567 | ||

| Number of counties | 414 | 707 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.08 | 0.12 | ||

*p<0.05 **p<0.01. Regressions adjusted for individual sex, race/ethnicity (minority regression only), urbanicity, region, income, education, poverty status, employment status, insurance status, and living alone or with spouse/partner.

Table 5 Logistic regressions of depression on ecological variables, stratified by race/ethnicity.

| Black and Hispanic | White, Asian | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Hypothesised ecological causal variables | ||||

| State social capital index | 0.49 | 0.17, 1.41 | 1.13 | 0.46, 2.74 |

| State generosity | 1.00 | 0.80, 1.25 | 1.06 | 0.85, 1.32 |

| Local income inequality | ||||

| County log per cent rich | 0.57 | 0.23, 1.43 | 0.78 | 0.28, 2.19 |

| Ecological confounders | ||||

| County log unskilled wage | 1.14 | 0.48, 2.70 | 1.32 | 0.60, 2.92 |

| County/state housing affordability index | 0.29 | 0.06, 1.38 | 0.67 | 0.16, 2.81 |

| County crime rate | 1.03 | 0.96, 1.12 | 0.97 | 0.88, 1.06 |

| County unemployment rate | 0.96 | 0.89, 1.04 | 0.87** | 0.78, 0.96 |

| County log per cent black | 1.21 | 0.97, 1.50 | 1.01 | 0.88, 1.16 |

| County log per cent Hispanic | 1.01 | 0.80, 1.28 | 0.91 | 0.76, 1.09 |

| County log mean income | 4.02 | 0.60, 26.81 | 2.64 | 0.49, 4.32 |

| County log mean years of education | 0.98 | 0.60, 1.60 | 0.75 | 0.47, 1.19 |

| County psych services index | 0.91 | 0.52, 1.57 | 2.18** | 1.21, 3.93 |

| County health services index | 0.39 | 0.07, 2.30 | 0.36 | 0.06, 2.18 |

| Number of participants | 2250 | 2567 | ||

| Number of counties | 414 | 707 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | ||

*p<0.05 **p<0.01. Regressions adjusted for individual sex, race/ethnicity (minority regression only), urbanicity, region, income, education, poverty status, employment status, insurance status, and living alone or with spouse/partner.

What this paper adds

There has been considerable attention in the literature to the hypothesised existence of effects of income inequality upon health outcomes. Yet income inequality has always been advanced only as a marker for other things, and there is very little literature testing the proposed causal pathways through which income inequality might be operating to affect population health. This paper simultaneously tests three proposed causal pathways in a single model that also controls for known individual and local area confounders. As such, the paper sheds light on the associations along the causal pathways between income inequality and health.

Table 4 reports results for the logistic regressions of reporting poor physical health, stratified by minority status. There are no significant differences across most of the variables. The exceptions are with social capital and income inequality. A higher index of social capital is associated with less depression among black people and Hispanics (OR 0.40, CI: 0.18 to 0.90), but not significantly so for white people. The county log‐per cent rich, non‐significant among black people and Hispanics, is a significant risk factor for white people (OR 2.60, CI: 1.22 to 5.56). Among the ecological confounders, a higher average county educational level is associated with less depression for white people, but not for black people and Hispanics.

Table 5 reports results for the logistic regressions of depression, stratified by minority status. There are no significant differences across most of the variables. The effect of local unemployment is more pronounced for white people (OR 0.87, CI: 0.78 to 0.96) than for black people or Hispanics, for whom it is not significant.

Policy implications

Health promotion efforts should focus on the positive part played by social capital in minority communities. In addition, and especially among white people, education about the possible adverse effects of invidious comparisons on health may be useful.

Discussion

This analysis takes the considerable literature on the effects of income inequality on health as a starting point, and tests for the significance of associations between two health outcomes and three posited possible causal mechanisms in a set of models with extensive controls for individual level covariates and potential ecological confounders. The purpose of this analysis is not to test causality, but rather to find out if associations are present that are implied by proposed causal mechanisms. As such, this analysis is a test of necessary conditions for the existence of proposed causal pathways, not of sufficient conditions. The results suggest that on the whole, the association between ecological variables and health outcomes is modest.

Within this broad conclusion, however, some important nuances emerge. Firstly, the level of state spending is associated with better physical health outcomes, even when both individual and area level income is controlled. This result may at first seem to lend some support to the hypothesis that income inequality operates on health through the generosity of local state spending. However, in unreported analyses, we found that the index of state generosity is positively associated with our measure of income inequality, controlling for the other ecological covariates. That is, notwithstanding previous results to the contrary,29 higher income inequality seems not to beget more miserly state spending, or if it does, this effect is overwhelmed by a negative feedback from state spending to income inequality, at least as the terms have been defined here. Therefore, the adverse effects of income inequality on health cannot be ascribed to miserly state spending.

Secondly, the measure of income inequality, the logged county percentage of households with annual income over $150 000, is significantly associated with worse self reported physical health, and this effect seems to be specific to white people. If one accepts that this analysis has controlled for much of the proposed causal pathways through the other ecological variables included, then the significance of the inequality variable may be ascribable to an association between invidious comparisons and health outcomes. Under this assumption, the role of invidious comparisons is only weakly and residually identified, so this interpretation must not be taken too conclusively. On the other hand, the fact that income inequality is significantly associated even controlling for this set of ecological confounders is consistent with the proposed causal mechanism of invidious comparisons. This result would buttress the conclusions of recent work that finds that an effect of subjective socioeconomic status on health outcomes, where the self definition of subjective socioeconomic status arises in part out of a comparison of oneself with those with whom one frequently interacts.42,51

Thirdly, the effects of unemployment are protective, at least against depression among white people. Because of the salience of individual level unemployment to mental health, it is not surprising to note a large ecological association as well. It is noteworthy, however, that the association is negative, with more local unemployment associated with less depression. This result may suggest that part of the psychic damage of unemployment may be that of being unemployed while others are employed. This result, too, is consistent with a role for social comparisons, albeit one that is quite distinct from that previously advanced in the literature.

County level mean income is not significant, in any of the regressions, but county level mean education is highly significantly associated with physical health. This result suggests that researchers would be well advised to control for area level educational effects in conducting further research in this area.

The import of these results lies in the extent to which several important ecological variables are simultaneously controlled. Analyses of ecological impacts depend for their validity on careful control for a variety of ecological confounders, many of which are correlated with each other, as seen in table 2.

An important limitation of this analysis is the failure to include a variable that directly measures the local area potential for invidious social comparisons. Given that there is a lingering effect of income inequality in the data even after extensive controls, it would be useful to better pin down the source of this effect. While the hypothesis that the effect is attributable to invidious comparisons is reasonable and is consistent with the data, it is dissatisfying not to be able to be more conclusive. A second limitation is that our measure of race/ethnicity may mask important differences within our racial/ethnic categories. The size of (and available variables in) the dataset do not permit further inferences about possible within‐group differences.

Conclusions and implications

If income inequality truly has a major impact on community health, one would expect to find a significant and meaningful effect of one or more of the ecological variables that have been hypothesised to constitute the causal mechanism. Such a strong effect does not leap out from this analysis. Instead, what emerges is a more nuanced story.

Higher levels of social capital are associated with better self reported physical health among black people and Latinos, but not among white people. Social capital is not associated with less depression among any racial/ethnic group. Controlling for a host of ecological variables, a measure of income inequality is associated with greater odds of poor self reported health among white people, but not among black people and Latinos, and is not associated with depression in either group.

Taken together these findings suggest that in certain situations some ecological factors are associated with self reported general health or with depression. Researchers may find it fruitful to recognise racial/ethnic differences in the effects of social capital and the role of invidious comparisons among white people.

While these results generate some provocative insights about the associations between income inequality and health outcomes, in the context of the conceptual model presented earlier, they also clearly show the need for future work to more definitively rule in or rule out causal pathways and confounding relations.

Contributions

FJZ and JFB each made substantial contributions to the collection of data for this project, to the analyses and interpretations reported; and to the drafting of the article. Each has approved this version.

Footnotes

Funding: this research was supported in part by an NIMH Career Development Award to Zimmerman, K01 MH064461‐03. It was approved by the UW IRB by certificate of exemption no 03‐6830‐X. The research here represents the opinions and views only of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the positions of NIMH, the NIH, or the University of Washington.

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- 1.Wilkinson R G. Income distribution and life expectancy. BMJ 1992304165–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy B P, Kawachi I, Prothrow‐Stith D. Income distribution and mortality: cross sectional ecological study of the Robin Hood index in the United States. BMJ 19963121004–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy B P, Kawachi I, Glass R.et al Income distribution, socioeconomic status, and self rated health in the United States: multilevel analysis. BMJ 1998317917–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deaton A, Lubotsky D. Mortality, inequality and race in American cities and states. Soc Sci Med 2003561139–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiscella K, Franks P. Individual income, income inequality, health, and mortality: what are the relationships? Health Serv Res 200035307–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franzini L, Ribble J, Spears W. The effects of income inequality and income level on mortality vary by population size in Texas counties. J Health Soc Behav 200142373–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gresenz C R, Sturm R, Tang L. Income and mental health: unraveling community and individual level relationships. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 20014197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn R S, Wise P H, Kennedy B P.et al State income inequality, household income, and maternal mental and physical health: cross sectional national survey. BMJ 20003211311–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawachi I, Kennedy B. The relationship of income inequality to mortality: Does the choice of indicator matter? In: Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Wilkinson R, eds. The society and population health reader. Vol 1. New York: New York Press, 1999112–122.

- 10.Lynch J, Harper S, Davey Smith G. Plugging leaks and repelling boarders—where to next for the SS income inequality? Int J Epidemiol 2003321029–36, 103740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellor J M, Milyo J. Reexamining the evidence of an ecological association between income inequality and health. J Health Polit Policy Law 200126487–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellor J M, Milyo J. Exploring the relationships between income inequality, socioeconomic status and health: a self‐guided tour? Int J Epidemiol 200231685–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellor J M, Milyo J. Is exposure to income inequality a public health concern? Lagged effects of income inequality on individual and population health. Health Serv Res 200338137–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturm R, Gresenz C R. Relations of income inequality and family income to chronic medical conditions and mental health disorders: national survey. BMJ 200232420–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subramanian S V, Blakely T, Kawachi I. Income inequality as a public health concern: Where do we stand? Health Serv Res 200338153–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Income inequality and health: What does the literature tell us? Annu Rev Public Health 200021543–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson R. The epidemiological transition: from material scarcity to social disadvantage? In: Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Wilkinson R, eds. The society and population health reader. Vol 1. New York: New York Press, 199937–46.

- 18.Wilkinson R G.Unhealthy societies—the afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge, 1996

- 19.Wolfson M, Kaplan G, Lynch J.et al Relation between income inequality and mortality: empirical demonstration. BMJ 1999319953–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian S V, Kawachi I. The association between state income inequality and worse health is not confounded by race. Int J Epidemiol 2003321022–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramanian S, Kawachi I. In defence of the income inequality hypothesis. Int J Epidemiol 2003321037–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Harper S.et al Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Q 2004825–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muntaner C, Eaton W W, Miech R.et al Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev 20042653–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig N. Exploring the generalisability of the association between income inequality and self‐assessed health. Soc Sci Med 2005602477–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson C, Liu X, Diez Roux A V.et al The effects of US state income inequality and alcohol policies on symptoms of depression and alcohol dependence. Soc Sci Med 200458565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weich S, Lewis G, Jenkins S P. Income inequality and the prevalence of common mental disorders in Britain. Br J Psychiatry 2001178222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muramatsu N. County‐level income inequality and depression among older Americans. Health Serv Res 2003381863–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson R G. Health, hierarchy, and social anxiety. Ann N Y Acad Sci 199989648–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan G A, Pamuk E R, Lynch J W.et al Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: analysis of mortality and potential pathways. BMJ 1996312999–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Easterlin R A. Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 19952735–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawachi I, Kennedy B P. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv Res 199934215–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almedom A M. Social capital and mental health: an interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Soc Sci Med 200561943–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macinko J, Starfield B. The utility of social capital in research on health determinants. Milbank Q 200179387–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramanian S V, Kim D J, Kawachi I. Social trust and self‐rated health in US communities: a multilevel analysis. J Urban Health 200279S21–S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subramanian S V, Lochner K A, Kawachi I. Neighborhood differences in social capital: a compositional artifact or a contextual construct? Health Place 2003933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawachi I, Kennedy B P, Glass R. Social capital and self‐rated health: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health 1999891187–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawachi I, Kennedy B P, Lochner K.et al Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. Am J Public Health 1997871491–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Hillemeier M.et al Income inequality, the psychosocial environment, and health: comparisons of wealthy nations. Lancet 2001358194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veenstra G. Location, location, location: contextual and compositional health effects of social capital in British Columbia, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2005602059–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veenstra G. Social capital, SES and health: an individual‐level analysis. Soc Sci Med 200050619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veblen T.The theory of the leisure class. New York: Modern Library, 2001: xvi, 298

- 42.Singh‐Manoux A, Adler N E, Marmot M G. Subjective social status: its determinants and its association with measures of ill‐health in the Whitehall II study. Soc Sci Med 2003561321–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glaeser E, Scheinkman J, Shleifer A. The injustice of inequality. Journal of Monetary Economics 200350199–222. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schnittker J, McLeod J D. The social psychology of health disparities. Annual Review of Sociology 200531105–125. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown G W, Bifulco A. Motherhood, employment and the development of depression. A replication of a finding? Br J Psychiatry 1990156169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krueger A B, Whitmore D M. The effect of attending a small class in the early grades on college‐test taking and middle school test results: evidence from project STAR. Economic Journal 20011111–28. [Google Scholar]

- 47.House J S. Understanding social factors and inequalities in health: 20th century progress and 21st century prospects. J Health Soc Behav 200243125–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stafford M, Marmot M. Neighbourhood deprivation and health: does it affect us all equally? Int J Epidemiol 200332357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Subramanian S V, Kawachi I. Whose health is affected by income inequality? A multilevel interaction analysis of contemporaneous and lagged effects of state income inequality on individual self‐rated health in the United States. Health and Place 200612141–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weich S, Twigg L, Holt G.et al Contextual risk factors for the common mental disorders in Britain: a multilevel investigation of the effects of place. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357616–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goodman E, Huang B, Wade T J.et al A multilevel analysis of the relation of socioeconomic status to adolescent depressive symptoms: does school context matter? J Pediatr 2003143451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caughy M O, O'Campo P J, Muntaner C. When being alone might be better: neighborhood poverty, social capital, and child mental health. Soc Sci Med 200357227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawachi I, Berkman L F. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health 200178458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saegert S, Winke G. Crime, social capital, and community participation. Am J Community Psychol 200434219–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morenoff J D, Sampson R J, Raudenbush S W. Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology 200139517–559. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sampson R J, Morenoff J D, Raudenbush S. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. Am J Public Health 200595224–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sampson R J, Raudenbush S W, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997277918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kawachi I, Kennedy B P, Wilkinson R G. Crime: social disorganization and relative deprivation. Soc Sci Med 199948719–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kennedy B P, Kawachi I, Prothrow‐Stith D.et al Social capital, income inequality, and firearm violent crime. Soc Sci Med 1998477–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bardhan P. Efficiency, equity and poverty alleviation: policy issues in less developed countries. Economic Journal 19961061344–1356. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murphy K M, Shleifer A, Vishny R W. Income distribution, market size, and industrialization. Quarterly Journal of Economics 1989104537–564. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zweimuller J. Inequality, redistribution, and economic growth. Empirica 2000271–20. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keefer P, Knack S. Polarization, politics and property rights: links between inequality and growth. Public Choice 2002111127–154. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ezzy D. Unemployment and mental health: a critical review. Soc Sci Med 19933741–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hamilton V H, Merrigan P, Dufresne E. Down and out: estimating the relationship between mental health and unemployment. Health Econ 19976397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lahelma E. Unemployment and mental well‐being: elaboration of the relationship. Int J Health Serv 199222261–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimmerman F J, Katon W. Socioeconomic status, depression disparities, and financial strain: what lies behind the income‐depression relationship? Health Econ 2005141197–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tesser A, Millar M, Moore J. Some affective consequences of social comparison and reflection process: the pain and pleasure of being close. Journal of Personality and Social Comparison 19885449–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brewer M B, Weber J G. Self‐evaluation effects of interpersonal versus group social comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 199466268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blanton H, Crocker J, Miller D T. The effects of in‐group versus out‐group social comparison on self‐esteem in the context of a negative stereotype. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 200036519–530. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Major B, Sciacchitano A, Crocker J. In‐group versus out‐group comparisons and self‐esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 199319711–721. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carpiano R M. Toward a neighborhood resource‐based theory of social capital for health: Can Bourdieu and sociology help? Soc Sci Med 200662165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krivo L J, Kaufman R L. Housing and wealth inequality: racial‐ethnic differences in home equity in the United States. Demography 200441585–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Drentea P, Lavrakas P J. Over the limit: the association among health, race and debt. Soc Sci Med 200050517–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bertrand M, Mullainathan S. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review 200494991–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Center for Human Resource Research The national longitudinal surveys NLSY79 user's guide. Columbus, OH: US Department of Labor, Ohio State University, 1999

- 77.US Department of Labor NLS handbook 2000. Washington: Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2000

- 78.Beekman A T, Deeg D J, Van Limbeek J.et al Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES‐D): results from a community‐based sample of older subjects in the Netherlands. Psychol Med 199727231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Husaini B A, Neff J A, Stone R H. Psychiatric impairment in rural communities. J Community Psychol 19797137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Knight R G, Williams S, McGee R.et al Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behav Res Ther 199735373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prescott C A, McArdle J J, Hishinuma E S.et al Prediction of major depression and dysthymia from CES‐D scores among ethnic minority adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 199837495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thomas J L, Jones G N, Scarinci I C.et al The utility of the CES‐D as a depression screening measure among low‐ income women attending primary care clinics. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies‐Depression. Int J Psychiatr Med 20013125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weissman M M, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M.et al Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol 1977106203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Irwin M, Artin K H, Oxman M N. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10‐item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D). Arch Intern Med 19991591701–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Furukawa T, Hirai T, Kitamura T.et al Application of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale among first‐visit psychiatric patients: a new approach to improve its performance. J Affect Disord 1997461–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andresen E M, Malmgren J A, Carter W B.et al Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES‐D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 19941077–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Duclos J ‐ Y, Esteban J, Ray D. Polarization: concepts, measurement, estimation. Econometrica 2004721737–1772. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Esteban J, Ray D. On the measurement of polarization. Econometrica 199462819–851. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goodman E, Adler N E, Kawachi I.et al Adolescents' perceptions of social status: development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics 2001108E31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Urban Institure's Welfare rules http://anfdata.urban.org

- 91.National Association of Home Builders and Wells Fargo Bank http://www.nahb.org/page.aspx/category/sectionID = 135

- 92.US Census County and City Data book http://www.census.gov/statab/www/ccdb.html

- 93.US Department of Labor http://www.bls.gov/cew/home.htm

- 94.Wildman J, Jones A M.Is it absolute income or relative deprivation that leads to poor psychological well being? A test based on individual‐level longitudinal data. York: University of York, 2005

- 95.Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W.et al Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta‐analysis. Am J Epidemiol 200315798–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Costello E J, Compton S N, Keeler G.et al Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. JAMA 20032902023–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fisher L, Van Belle G.Biostatistics: a methodology for the health sciences. New York: Wiley, 1993: xxii, 991

- 98.Maas C J M, Hox J J. Robustness issues in multilevel regression analysis. Statistica Neerlandica 200458127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goldberger A S.Introductory econometrics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998: xii, 241