Abstract

Objectives

To identify independent predictors for development of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients and to develop a simple prediction rule for pressure ulcer development.

Design

The Prevention and Pressure Ulcer Risk Score Evaluation (prePURSE) study is a prospective cohort study in which patients are followed up once a week until pressure ulcer occurrence, discharge from hospital, or length of stay over 12 weeks. Data were collected between January 1999 and June 2000.

Setting

Two large hospitals in the Netherlands.

Participants

Adult patients admitted to the surgical, internal, neurological and geriatric wards for more than 5 days were eligible. A consecutive sample of 1536 patients was visited, 1431 (93%) of whom agreed to participate. Complete follow up data were available for 1229 (80%) patients.

Main outcome measures

Occurrence of a pressure ulcer grade 2 or worse during admission to hospital.

Results

Independent predictors of pressure ulcers were age, weight at admission, abnormal appearance of the skin, friction and shear, and planned surgery in coming week. The area under the curve of the final prediction rule was 0.70 after bootstrapping. At a cut off score of 20, 42% of the patient weeks were identified as at risk for pressure ulcer development, thus correctly identifying 70% of the patient weeks in which a pressure ulcer occurred.

Conclusion

A simple clinical prediction rule based on five patient characteristics may help to identify patients at increased risk for pressure ulcer development and in need of preventive measures.

Keywords: decubitus ulcer, nursing, risk assessment, prognosis

Patients admitted to hospital or otherwise confined to bed, chair, or wheelchair are at risk for the development of pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers pose a major burden for health care in western countries. In the Netherlands more than 1% of the total budget for health care is spent on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers or prolonged hospital stay once a pressure ulcer develops.1

The prevalence of pressure ulcers grade 1–4 ranges from 10% to 23% in hospitalized patients in westernized societies.2,3 The proportion of newly hospitalized patients developing pressure ulcers ranges between 7% and 38%.2 We have found that the incidence rate of pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse in patients admitted to general wards varies from 2% to 8% depending on medical specialty.4 Preventive measures and treatment are expensive and labour intensive. Patients with a clear risk of developing pressure ulcers should therefore be identified.

To detect high risk patients, several risk assessment scales have previously been developed.5,6,7 At least 40 risk assessment scales have been described.8 Most scales reflect expert opinion, literature review, or adaptation of an existing scale. Neither the risk factors nor the weights attributed to them have been determined using empirical data and adequate statistical techniques.8,9 Only six risk assessment scales have been tested for their predictive validity.8 Moreover, the majority of the studies that evaluated the risk assessment scales had methodological limitations.8 The results of these studies varied and little evidence of predictive value or accuracy of the scales was available.5,7,8,9,10,11,12 Consequently, the broadly advocated advice to use risk assessment scales and base decisions about measures to prevent pressure ulcers on the outcome of these scales appears to lead to ineffective and inefficient preventive measures for most patients.

The aim of this study was first to identify independent predictors for the development of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients and then, based on these predictors, to derive a prediction rule to assess the risk of developing pressure ulcers in patients admitted to hospital.

Methods

Study design and patients

The prevention and Pressure Ulcer Risk Score Evaluation study (prePURSE) is a prospective cohort study of patients admitted to the University Medical Centre Utrecht (UMCU) and Meander Medical Centre Amersfoort, the Netherlands between January 1999 and June 2000. Patients from the surgical, internal medicine, neurological, and geriatric wards participated in the study. Patients older than 18 years with an expected admission of at least 5 days without pressure ulcers were eligible. The study population has been described in detail in a previous paper on the routine use of risk assessment scales.12 The main characteristics of the 1229 patients who participated in the study are shown in table 1. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht.

Table 1 Characteristics of study patients (n = 1229).

| Characteristic | No (%)* |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 60.1 (16.7) |

| Female | 673 (54.8%) |

| Hospital | |

| University Medical Centre Utrecht | 783 (63.7%) |

| Meander Medical Centre Amersfoort | 446 (36.3%) |

| Ward | |

| Surgical | 759 (61.8%) |

| Internal Medicine | 275 (22.4%) |

| Neurology | 122 (9.9%) |

| Geriatrics | 73 (5.9%) |

| No of patient weeks (N) | 2190 |

| Preventive measures (N (no of patient weeks))† | 57 (101) |

*Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise.

†With regard to prevention, only 57 of the 1229 patients (101 of 2190 patient weeks) received preventive measures (4.6%). Sixteen of these patients received the measures after the pressure ulcer had developed (that is, as treatment), and in two patients the prevention failed.

Data collection

A research nurse visited patients within 48 hours of admission and once a week thereafter until either they developed a pressure ulcer, or they were discharged, or they had stayed in hospital for more than 12 weeks. At each visit patients were examined for the presence of pressure ulcers and information on preventive measures was collected. Preventive measures were considered present if, at the time the skin was inspected, the patient had a pressure reducing mattress or bed, where necessary combined with a pressure reducing cushion while seated, or was repositioned regularly. The information on repositioning was gathered by asking the patient or, if the patient could not answer, by checking the care plan.

Outcome definition

Pressure ulcers were classified into four grades following the classification of the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.13 Pressure ulcers of grade 2 or worse were included.

Potential predictors

Information on potential prognostic determinants mentioned in the literature was obtained (see Appendix 1 at the end of the paper and online at www.qshc.com/supplemental). A comprehensive review of risk factors for pressure ulcer development14 and an unpublished systematic review of risk assessment scales were used to select these potential prognostic determinants.15

Statistical analysis

The 1229 patients yielded 2190 patient weeks of observation time (table 1). Patient weeks in which the patients received preventive measures and did not develop pressure ulcers (n = 83) were excluded from the analysis because it was impossible to distinguish the effects of prevention from false positive cases. We also excluded patient weeks in which information on preventive measures was missing (n = 28), and those in which the patient was admitted to the ICU (n = 19). In this study pressure ulcers developed in nine (47%) of the ICU patient weeks. Other studies confirm this high incidence rate, suggesting that ICU patients have a much higher risk of developing pressure ulcers than patients admitted to general wards. The exclusions above resulted in a database with 2060 patient weeks.

For the analysis we considered each assessment as separate and independent information. As one patient may contribute up to 12 weeks to the dataset, we also performed an analysis accounting for week of admission. Week of admission was defined as the number of weeks the patient had been admitted to the hospital up to that moment. Week of admission appeared not to have a significant impact on the prediction of pressure ulcer occurrence.

The problem of missing data was resolved by carrying out a complete case analysis. Data were missing in only 35 patient weeks (1.7%), including 4 patient weeks in which pressure ulcers developed. The analysis was therefore performed on 2025 patient weeks, including 121 cases. As the data were missing completely at random and the data were prospectively gathered, this analysis results in unbiased estimates.

Age was categorized into three categories: ⩽49 years (reference category), 50–74 years, and ⩾75 years. Weight at admission was categorized into three categories: ⩽54 kg, 55–94 kg (reference category), and ⩾95 kg. Abnormal appearance of the skin was considered present when the skin was discoloured, dry, damaged (excluding grade 2 or worse pressure ulcers) or when localized oedema was present. All other variables with more than two categories were dichotomized based on underlying pathophysiology of the risk factors for development of pressure ulcers.

Associations between potential prognostic determinants and pressure ulcers in the subsequent week were examined using univariate logistic regression analysis. Predictors univariately associated with outcome (p value <0.15), observed frequently, and relatively easy to obtain in nursing practice were included in a multivariate logistic regression model.16 The model was reduced by excluding predictors from the model with a p value >0.10 and the goodness of fit was estimated. The prognostic ability to discriminate between patients with and without pressure ulcers was estimated using the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC).16

Bootstrapping techniques were used to validate the model—that is, to adjust the estimated model performance and regression coefficients for overoptimism or overfitting.16,17 Random bootstrap samples were drawn with replacement (100 replications) from the dataset consisting of all patients (n = 1229). The multivariable selection of variables was repeated within each bootstrap sample. The performance of the model after bootstrapping can be considered as the expected performance of the model in future patients.

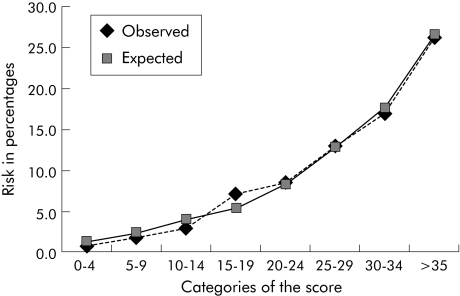

The final model was transformed into a prediction rule by multiplying the regression coefficients by 10 and subsequent rounding to the nearest integer. By assigning points for each variable and adding the results, a score was obtained for each individual patient. Patients were classified according to their risk score. The risk scores were divided into eight categories of five points each, and the proportion of patient weeks with pressure ulcers was calculated for several categories of risk scores. Finally, the observed and expected risks for pressure ulcer development per category of the score were calculated, and the fit of the model was visualized by plotting the observed risk against the expected risk per category of the score.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 9.0 (SPSS Inc) and S‐Plus.

Results

The overall incidence rate of pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse observed was 0.06 per patient week (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05 to 0.07)—that is, during 2025 patient weeks 121 patients developed pressure ulcers. The severity and anatomical location of the pressure ulcers are reported elsewhere.4

Table 2 shows the univariate correlates associated with pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse that were selected for multivariate analysis (p<0.15).

Table 2 Univariate correlates (p<0.15) of the presence or absence of pressure ulcers (PU) grade 2 and higher.

| Variable | PU present (n = 125) n (%) | PU absent (n = 1933) n (%) | Odds ratio† | p value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| ⩽49 | 16 (12.8) | 458 (23.7) | RC | |

| 50–74 | 59 (47.2) | 971 (50.2) | 1.78 | |

| ⩾75 | 50 (40.0) | 504 (26.1) | 3.01 | |

| Weight at admission (kg) | 0.09 | |||

| ⩽54 | 13 (10.7) | 193 (10.1) | 1.15 | |

| 55–94 | 94 (77.0) | 1586 (82.9) | RC | |

| ⩾95 | 15 (12.3) | 133 (7.0) | 1.91 | |

| Medical specialty | ||||

| Surgical | 86 (68.8) | 1068 (55.3) | 1.76 | 0.005 |

| Other (Medical, Neurology or Geriatric) | 39 (31.2) | 865 (44.7) | RC | |

| Mobility | ||||

| Slightly limited/fully mobile | 97 (77.6) | 1679 (86.9) | RC | |

| Immobile/very limited | 28 (22.4) | 254 (13.1) | 1.96 | 0.003 |

| Activity | ||||

| No limitation/walks occasionally | 78 (62.4) | 1343 (69.5) | RC | |

| Chair or bedfast | 47 (37.6) | 590 (30.5) | 1.41 | 0.07 |

| Abnormal appearance of the skin | 77 (61.6) | 1468 (75.9) | 2.06 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 24 (19.2) | 264 (13.7) | 1.54 | 0.07 |

| Previous pressure ulcer | 15 (12.0) | 154 (8.0) | 1.58 | 0.11 |

| Incontinence | ||||

| Continent/only urine incontinence | 116 (93.5) | 1851 (96.0) | RC | |

| Fecal incontinence/doubly incontinent | 8 (6.5) | 77 (4.0) | 1.81 | 0.13 |

| Friction/shear | ||||

| No problem | 73 (58.9) | 1388 (72.0) | RC | |

| Potential/actual problem | 51 (41.1) | 539 (28.0) | 1.89 | 0.001 |

| Surgery in coming week | 67 (53.6) | 710 (36.8) | 2.08 | <0.001 |

RC, reference category.

*Number of patient weeks in which the variable was available.

†Adjusted for week of admission.

In the multivariate analysis age, weight at admission, abnormal appearance of the skin, friction and shear, and planned surgery in coming week emerged as independent predictors (table 3). The AUC of this model was 0.72 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.76). The regression coefficients of the independent predictors after bootstrapping are shown in table 3. The AUC of the model after bootstrapping was 0.70.

Table 3 Independent predictors of pressure ulcers grade 2 and higher in hospitalized patients.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Regression coefficient* | Contribution to score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| ⩽49 | RC | 0 | |

| 50–74 | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.1) | 0.6 | 6 |

| ⩾75 | 2.8 (1.5 to 5.2) | 1.0 | 10 |

| Weight at admission (kg) | |||

| ⩽54 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.4) | 0.3 | 3 |

| 55–94 | RC | 0 | |

| ⩾95 | 2.2 (1.2 to 3.9) | 0.8 | 8 |

| Abnormal appearance of skin | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.1) | 0.7 | 7 |

| Friction/shear | |||

| No problem | RC | 0 | |

| Potential/actual problem | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.2) | 0.7 | 7 |

| Surgery in coming week | 4.0 (2.5 to 6.5) | 1.4 | 14 |

| Week of admission | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 0.01 | – |

Prediction rule: score = 6 (if age 50–74) + 10 (if age ⩾75) + 3 (if weight ⩽54 kg) + 8 (if weight ⩾95 kg) + 7 (if abnormal appearance of the skin) + 7 (if potential/actual problem friction and shear) + 14 (if surgery in coming week).

*Regression coefficient after bootstrapping.

A prediction rule was constructed by assigning points for each variable weighted in accordance with the regression coefficient (table 3). Week of admission was not included in the final prediction rule. A total score was computed for each individual patient, ranging from 0 to 41. The AUC of this score was 0.71 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.76). In table 4 the numbers of patient weeks with and without pressure ulcers and the observed risk for pressure ulcer development across selected categories of the score are presented. Figure 1 shows that the prediction rule yields an accurate estimate of risk (that is, it is well calibrated). At a cut off score of 20 the prediction rule correctly identified 70% (85/121) of the patient weeks in which a pressure ulcer grade 2 or worse occurred. Also, 42% (842/2025) of the total patient weeks were identified as at risk for development of pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse. In the patient group with a risk score of ⩾20, 10% of the patients developed pressure ulcers, compared with 3% in the group with a risk score of <20. Conversely, 40% (757/1904) of the patient weeks in which no pressure ulcers developed were falsely identified as at risk for development of pressure ulcers (false positives).

Table 4 Number (%) of patient weeks with pressure ulcers (PU) across categories of the risk score.

| Risk score | Total no of patient weeks (n = 2025) n (%) | PU present (n = 121) n (%) | PU absent (n = 1904) n (%) | Risk (PU/week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 137 (6.8) | 1 (0.8) | 136 (7.2) | 0.7% |

| 5–9 | 341 (16.8) | 6 (5.0) | 335 (17.6) | 1.7% |

| 10–14 | 510 (25.2) | 15 (12.4) | 495 (26.0) | 2.9% |

| 11–19 | 195 (9.6) | 14 (11.6) | 181 (9.5) | 7.2% |

| 20–24* | 647 (32.0) | 55 (45.5) | 592 (31.1) | 8.5% |

| 25–29* | 123 (6.1) | 16 (13.2) | 107 (5.6) | 13.0% |

| 30–34* | 53 (2.6) | 9 (7.4) | 44 (2.3) | 17.0% |

| ⩾35* | 19 (0.9) | 5 (4.1) | 14 (0.7) | 26.3% |

*Patient weeks at risk at proposed cut off point of 20.

Figure 1 Observed versus predicted risk across categories of the score.

Discussion

The incidence rate of pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse was 0.06 per patient week (95% CI 0.05 to 0.07). A clinical prediction rule consisting of only five easily obtainable patient characteristics enabled identification of the majority of patient weeks at risk for development of pressure ulcers. At a cut off score of 20, the prediction rule correctly predicted 70% of the patient weeks in which pressure ulcers developed, while 42% of the patient weeks were identified as at risk for development of pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse.

To appreciate our results, some aspects need to be discussed. Firstly, we considered the assessments in each patient week as separate and independent information. The data, however, are not fully independent, as one patient may contribute up to 12 weeks to the dataset. Therefore, initially we adjusted for week of admission in the analysis. However, week of admission had no association with the occurrence of pressure ulcers in either the univariate or multivariate analyses. We therefore considered that a possible dependency between the patient weeks had no major impact on the results of the current study. Also, weekly assessment without taking into consideration the score calculated in the prior week is in accordance with current guidelines.

Secondly, we observed patients once a week. As a grade 1 pressure ulcer (that is, non‐blanchable erythema) is a reversible lesion,18 it was impossible to monitor these ulcers accurately and reliably at this observation frequency. We therefore limited the analysis to pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse. Older lesions of the skin would still have been visible as a scab at a subsequent visit. Consequently, we are confident no pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse have been missed.

Thirdly, preventive measures may attenuate the association between the potential predictors and the development of pressure ulcers. Our goal was to develop a prediction rule that may be used to allocate preventive measures to patients who did not yet receive any. We therefore excluded patients who received preventive measures and did not develop pressure ulcers (n = 83, 3.8%). Indeed, in these patients it cannot be determined whether pressure ulcers would have developed had preventive measures not been taken—that is, it was not possible to distinguish effective prevention from false positive cases. We believe that excluding these patient weeks did not bias our results. Entering prevention into the logistic regression model would have resulted in a model that predicted pressure ulcers conditional on the policy of prevention followed at present. This would have been useful if prevention was standardized—that is, given to the same patients for the same reason in both hospitals. In practice, however, prevention was given quite randomly based on the nurse's clinical judgement. We feel that excluding these patient weeks allowed us to develop a risk assessment scale for patients who had not yet received prevention. Moreover, very few patients received prevention in this study (4.6%).

We selected a population sample that may be considered generalisable to the common hospitalized patient in the Netherlands—that is, patients with a predicted stay of ⩾5 days. However, the prediction rule may not be applicable to patients in general wards outside this setting such as children and patients in other healthcare settings. In countries where the hospital admission time is shorter (where patients are transferred quickly from acute care to other facilities), more research is needed to study whether it is possible to use the prediction rule in these facilities. Although we included in the study several patients (n = 19 patient weeks) who were admitted to the ICU, we excluded them from the analysis because pressure ulcers occurred in 47% of these weeks. The high incidence rates in ICU patients have been reported previously,2 indicating that the ICU population possibly comprises a specific subgroup which is different from the average hospital population. We feel that exclusion of ICU patient weeks resulted in a more homogeneous population.

A further point of concern may be that we excluded all patients admitted for less than 5 days. We chose to exclude all patients with shorter hospital stay from the analysis as it is generally assumed that pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse may only become apparent 3–5 days after the lesion has been caused.19,20 A follow up time of at least 5 days is therefore essential for detection.

Finally, patients with pressure ulcers at admission were excluded because the aim of this study was to develop a prediction rule for first occurrence of pressure ulcers. Moreover, patients with pressure ulcers may be considered at risk of developing pressure ulcers in other sites21 and should therefore always receive preventive measures, regardless of their score.

The risk factors found in our study have been identified before. In fact, many of the currently available risk assessment scales comprise one or more of these predictors. However, none of the current risk assessment scales uses all of these predictors. Furthermore, our prediction rule is based on regression modelling, thus accounting for the mutual associations between predictors. In contrast, the available risk assessment scales for hospitalized patients are based on expert opinion, literature review, or adaptation of existing scales.9 The weights we assigned to each of the predictors were based on the regression coefficients, while the weights in the previous risk assessment scales were attributed subjectively.

A prediction rule with an AUC of 0.70 has limited discriminative capacity.22 However, it offers a major improvement compared with the currently available risk assessment scales which have AUCs varying from 0.55 to 0.61.12 Moreover, in view of the rather low incidence rate (in statistical terms) of pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse, it may be difficult to improve the prediction of pressure ulcers further in the average hospital population. It might be more efficient to start treatment or prevention once grade 1 ulcers occur, rather than to try to predict and prevent them.23 However, using this approach requires training in assessment of grade 1 ulcers,24 very regular and careful observation of patients, and the ability to start prevention immediately if non‐blanchable erythema is observed.25

Another issue related to application in daily practice pertains to validity. Although we showed that the model was robust with bootstrapping techniques (the AUC only shrunk from 0.72 to 0.70 and regression coefficients changed marginally), final proof of validity and cost effectiveness should be obtained in a separate group of comparable hospitalized patients. Validity in other settings such as nursing homes and ICU wards should be evaluated separately.

Lastly, we used a cut off point of 20 for our clinical prediction rule. This cut off would suggest that, in 42% of the patient weeks, preventive measures should be adopted. This percentage is higher than the 20–35% that would have to receive preventive measures had we used the currently available risk assessment scales.12 However, with our clinical prediction rule, timely treatment would be given to 70% of the patients who would otherwise certainly have developed pressure ulcers, compared with 31–50% of patients using the current risk assessment scales. Although the proposed prediction rule would result in 40% false positive predictions, we consider this relatively high percentage acceptable. The consequences of misclassification, such as possible discomfort from receiving preventive measures and additional resource use, appear to be counterbalanced by the profound impact of pressure ulcers on quality of life26 and resource use for treatment. One might still consider a strategy resulting in overtreatment to be a waste of resources, but we certainly attained a considerable improvement over currently available risk assessment scales.12 Further research is necessary to assess the financial and patient related consequences of this misclassification.

In conclusion, the majority of pressure ulcers in patients hospitalized to general wards can be predicted using a prediction rule based on five easily obtainable patient characteristics. By allocating preventive measures to 42% of the patients, 70% of patients who otherwise would have developed pressure ulcers grade 2 or worse will receive the measures in time. However, additional research is required to confirm the validity of the prediction rule in other settings.

A more detailed version of Appendix 1 is available online at www.qshc.com/supplemental

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Health Research and Development Council of the Netherlands who funded the study, Chantal Cornelis for assistance with data collection, and Bep Verkerk for assistance with data management. They also thank the participants of the prePURSE study group for their support. The participants of the prePURSE study group were: A Algra, Julius Centre for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Centre Utrecht, and Department of Neurology, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands; M T Bousema, Department of Dermatology, Meander Medical Centre Amersfoort, the Netherlands; E Buskens, D E Grobbee, M Grypdonck, L Schoonhoven, A J P Schrijvers, Julius Centre for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands; J J M Marx, Department of Internal Medicine, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands; B van Ramshorst, Department of Surgery, Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

Appendix 1

Description of potential prognostic determinants mentioned in literature. For full details see online version at www.qshc.com/supplemental.

| Category* | Determinant | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical specialty† | Sex27 |

| 2 | Mobility14,27,28,29,30† | Mental condition28,29 |

| Activity14,28,29,30† | Sensory perception27,28,29,30 | |

| Incontinence27,28,29,30† | Urine catheter27,28† | |

| Moisture30 | Friction and shear14,30† | |

| Pain15 | Surgery31† | |

| Length of surgery31† | ||

| 3 | Current smoking14,17 | Malnutrition at admission14 |

| Normal skin27† | Broken skin27 | |

| Dry skin27† | Oedema (localized)27† | |

| Discoloration of skin27† | Tube feeding30 | |

| Total parenteral feeding30† | Oral feeding14,30 | |

| Appetite27 | Nutritional condition27,28 | |

| Oral fluid intake14,30 | IV drip30 | |

| Medication use14,27,28 | Fever14,28 | |

| Hypertension14 | Hypotension14 | |

| Hemoglobulin level14† | Former pressure ulcer21† | |

| Albumin <35 g/l at admission14 | Leukocytes at admission14 | |

| Lymphocyte count <1200 mm3 at admission14 | Total protein <60 g/l at admission14 | |

| Comorbidity, diagnosis, complications14 | Diabetes14,27,28† | |

| Spinal cord lesion14,27,28 | ||

| 1, 3 | Age14,27,28† | |

| 2, 3 | Height14 | Weight at admission14† |

| Body mass index at admission14,27† | Neurological impairment28; | |

| General physical condition29 | ||

* 1, demographic data; 2, risk factors influencing the duration and intensity of pressure and shearing forces; 3, risk indicators influencing tissue tolerance.

†p<0.15 (univariate analysis).

Footnotes

This study was funded by the Health Research and Development Council of the Netherlands.

Competing interests: none declared.

A more detailed version of Appendix 1 is available online at www.qshc.com/supplemental

References

- 1.Health Council of the Netherlands Pressure ulcers. Publication no 1999/23. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands, 1999

- 2.Cuddigan J, Ayello E A, Sussman C. eds. Pressure ulcers in America. Prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. Reston, VA: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), 2001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bours G J J W, Halfens R J G, Huijer Abu‐Saad H.et al Prevalence, prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: descriptive study in 89 institutions in the Netherlands. Res Nurs Health 20022599–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoonhoven L.Prediction of pressure ulcers: problems and prospects. PhD thesis. The Netherlands: University of Utrecht, 2003

- 5.Edwards M. The rationale for the use of risk calculators in pressure sore prevention, and the evidence of the reliability and validity of published scales. J Adv Nurs 199420288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel ( E P U A P.Pressure ulcer prevention guidelines. Oxford: EPUAP, 1999, Available at http://www.epuap.org/glprevention.html (accessed 12 January 2005)

- 7.Clark M, Farrar S. Comparison of pressure sore risk calculators. In: Harding KG, Leaper Dl, eds. Proceedings of the first European conference on advances in wound management. Cardiff, UK. London: Macmillan Magazines, 1991158–162.

- 8.Nixon J, McGough A. Principles of patient assessment: screening for pressure ulcers and potential risk. In: Morison M, ed. The prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. London: Mosby, 200155–74.

- 9.Haalboom J R, den Boer J, Buskens E. Risk‐assessment tools in the prevention of pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 19994520–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton F. An analysis of the literature pertaining to pressure sore risk‐assessment scales. J Clin Nurs 19921185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards M. Pressure sore risk calculators: some methodological issues. J Clin Nurs 19965307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoonhoven L, Haalboom J R E, Bousema M T.et al Predicting pressure ulcers in a prospective cohort: do the risk assessment scales merit routine use? BMJ 2002325797–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel ( E P U A P.Guideline on treatment of pressure ulcers. Oxford: EPUAP, 1999, Available at http://www.epuap.org/gltreatment.html (accessed 12 January 2005)

- 14.Defloor T. The risk of pressure sores: a conceptual scheme. J Clin Nurs 19998206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGough A.A systematic review of the effectiveness of risk assessment scales used in the prevention and management of pressure sores. MSc thesis. Department of Health Sciences and Clinical Evaluation, University of York 1999

- 16.Harrell‐FE J, Lee K L, Mark D B. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 199615361–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steyerberg E W, Harrell F‐E J, Borsboom G J.et al Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 200154774–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maklebust J. Pressure ulcers: etiology and prevention. Nurs Clin North Am 198722359–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinsdale S M. Decubitus ulcers: role of pressure and friction in causation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 197455147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy N. Effects of mechanical stress on lymph and interstitial fluid flows. In: Bader DL, ed. Pressure sores. Clinical practice and scientific approach. London: Macmillan, 1990203–220.

- 21.Defloor T.Drukreductie en wisselhouding in de preventie van decubitus [Pressure reduction and repositioning in the prevention of pressure ulcers]. PhD thesis. Belgium, University of Gent 2000

- 22.Weinstein M C, Fineberg H V.Clinical decision analysis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 198098–102.

- 23.Vanderwee K, Defloor T, Grypdonck M H F. Non‐blanchable erythema as a predictor of pressure ulcer lesions: an alternative approach to risk assessment. In: Book of abstracts, 6th European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Open Meeting 2002

- 24.Defloor T, Schoonhoven L, Vanderwee K.et al Reliability of the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel classification system. J Adv Nurs 2005. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Defloor T, Grypdonck M F. Validation of pressure ulcer risk assessment scales: a critique. J Adv Nurs 200448613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langemo D K, Melland H, Hanson D.et al The lived experience of having a pressure ulcer: a qualitative analysis. Adv Skin Wound Care 200013225–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waterlow J. Pressure sores: a risk assessment card. Nurs Times. 1985;81: 49, 51, 55, [PubMed]

- 28.Dutch Institute for Health Care Improvement (CBO) Herziening consensus decubitus [Revision consensus pressure ulcers]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: CBO, 1992

- 29.Norton D, McLaren R, Exton‐Smith A N. Pressure sores. In: An investigation of geriatric nursing problems in hospital. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1975194–237.

- 30.Bergstrom N, Braden B J, Laguzza A.et al The Braden Scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Res 198736205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoonhoven L, Defloor T, van der Tweel I.et al Risk indicators for pressure ulcers during surgery. Appl Nurs Res 200216163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.