Abstract

Objectives

(1) To identify the extent to which information provided by parents in the pediatric emergency department (ED) can drive the assessment and categorization of data on allergies to medications, and (2) to identify errors related to the capture and documentation of allergy data at specific process level steps during ED care.

Methods

An observational study was conducted in a pediatric ED, combining direct observation at triage, a structured verbal interview with parents to ascertain a full allergy history related to medications, and chart abstraction. A comparative standard for the allergy history was established using parents' interview responses and existing guidelines for allergy. Errors associated with ED information management of allergy data were evaluated at five steps: (1) triage assessment, (2) treating physician's discussion with parent, (3) treating nurse's discussion with parent, (4) use of an allergy bracelet, and (5) documentation of allergy history on medication order sheets.

Results

256 parent‐child dyads were observed at triage; 211/256 parents (82.4%) completed the structured verbal interview that served as the basis for the comparative standard (CS). Parents reported a total of 59 medications as possible allergies; 56 (94.9%) were categorized as allergy or not based on the CS. Twenty eight of 48 patient cases were true allergies by guideline based assessment. Sensitivity of triage for detecting true medication allergy was 74.1% (95% confidence interval (CI) 53.7 to 88.9). Specificity of triage personnel for correctly determining that no allergy existed was 93.2% (95% CI 88.5 to 96.5). Physician and nursing care had performance gaps related to medication allergy in 10–25% of cases.

Conclusions

There are significant gaps in the quality of information management regarding medication allergies in the pediatric ED.

Keywords: patient centred care, medical history taking, drug hypersensitivity, information management, emergency medicine, children

Safe and effective care in emergency medicine require information management practices that support data accuracy and completeness across interrelated steps of capture, analysis, and integration. Critical data elements must be accurately determined and disseminated early in the care process to allow the system and individual stakeholders to effectively integrate and use these data.1

The emergency department (ED) epitomizes a high risk setting for patient safety as defined by the Committee on Data Standards of the Institute of Medicine (United States): multiple providers involved in the care of individual patients, high acuity, a setting prone to distractions from noise and crowding, need for rapid decision making, and communication barriers.2 In the ED, verbal communication between patients and clinical providers and documentation of this exchange remains variable and often incomplete for key data elements.3,4,5 Communication in pediatric emergency care, wherein the parent serves as a proxy reporter alongside the child in question, can be even more problematic.

Patient centered care has been promoted as a key aspect of high quality health systems for the 21st century.6 Few examples exist, however, where patients are placed at the center of the information management process in emergency medicine. A growing literature suggests that direct patient entry of health data (either on paper or using computer interfaces) can improve documentation made by ED based clinical providers.7,8,9,10

The performance of pediatric ED systems was studied with regard to information management of a specific data element—namely, allergies to medications. This data element represents critical knowledge for every clinical provider and provides an opportunity to measure system performance across the iterative steps of data capture, documentation, and integration. The questions of interest for this work were two interrelated ones: “Is the right answer obtained?” and “Is the right answer communicated and integrated into the clinical care delivery process?”

The specific aims of this study were to: (1) identify the extent to which parent provided information can drive the assessment and categorization of data on allergies to medications, and (2) to identify errors related to the capture and documentation of allergy data at specific process level steps during pediatric ED care.

Methods

Overview of study

An observational study was conducted in a pediatric ED to explore data capture, communication, and documentation for medication specific allergies. We surveyed care at nursing triage and then later when the patient was placed in a treatment room for definitive care. The evaluation at triage consisted of direct observation of verbal communication between the parent and triage staff and review of documentation. Standard functions for nursing triage in the ED setting include rapid and accurate assessment of patient acuity, initial paper based documentation of key patient specific historical and observational data, and initial care tasks intended to stabilize the patient's condition and begin the process of treatment and evaluation. The evaluation of distal care events included a structured interview with the parent and direct observation of an alert bracelet for allergies on the patient's extremity. Care related to administration of medications was assessed via a retrospective chart review of all paper based medication order sheets and documents created by physicians in an electronic medical record.

Setting and subjects

A convenience sample of parent‐child dyads arriving for care at a single tertiary care pediatric ED during summer 2004 was observed and recruited. Parent‐child dyads where the child was less than 18 years of age and the primary language of the parent was either English or Spanish were included. To select for visits where the likelihood of allergy data would be relevant to prescribing, cases of trauma where the parent‐child dyad reported an injury as the chief complaint were excluded. During hours when the research assistant was present (weekday afternoons and evenings), consecutive parent‐child dyads were observed at triage and subsequently approached to complete an in‐person interview. To allow for a single research assistant to track parent‐child dyads initially observed at triage, no more than 10 consecutive observations at a time were completed at triage before attempts were made to conduct interviews with parents.

The project was conceived and executed as a quality improvement project focused on system performance with the goal of improving care with regard to medication safety. The Committee on Clinical Investigation at Children's Hospital Boston does not consider projects that are designed to improve clinical care and better conform to standards as research requiring formal review, provided that participants' data remain anonymous. We solicited verbal permission from parents to complete the in‐person interview.

Methods of measurement

Direct observation of care and documentation at triage

A trained observer fluent in English and Spanish witnessed the interaction between triage staff and parent‐child dyads and recorded information on a structured data form. The purpose of the observation was described to triage nursing staff as an improvement project to investigate how the ED gathered and used information from parents. The observer recorded both the questions asked by triage personnel for the topic of allergies as well as parents' responses to those question(s). We recorded whether triage personnel clarified any answers given by the parent regarding allergies.

Direct survey of parents in treatment room

Subsequent care given by treating physician(s) and nurse(s) after the parent‐child dyad had been taken to a treatment room was evaluated. No direct observations of nurse‐parent or physician‐parent interactions in the treatment rooms were made. Parents were approached by the bilingual research assistant and asked to participate in a brief interview about “taking medicines and any problems or reactions your child may have had to medicines”. Parents who did not wish to participate in the interview were asked if the research assistant could examine the child's extremity to look for an allergy bracelet. In this ED, allergy bracelets are a patient level safety mechanism and are placed on the patient at the point of triage by the nurse who determines that an allergy to medication exists.

A structured verbal interview with the parent (hereafter called the comparative standard, CS) explored potential allergies to medications. The CS represents a best effort, history driven assessment and is not an infallible standard. The CS was based in part on a previously published screen for medication allergies.11 With the goal of maximal sensitivity, the CS asked “Has your child ever had a problem or reaction to any medicine that was given?” An answer of “yes” or “not sure” prompted a report of the medication name. If the parent was not able to remember the exact name, they were queried as to the category of medication (“what type of medicine was it?”). Once a given medicine or category of medication was identified, clarifying questions were asked to identify features of the reaction. For details of the full interview see the Addendum available online at http://www.qshc.com/supplemental.

The CS also investigated the parents' perception of communication with nurses and doctors regarding allergies. The following questions were asked: (1) “Did the examining physician review the allergy history with the parent?” and (2) “Did the treating nurse review the allergy history with the parent?”

Chart abstraction

Final review of the care process occurred through a structured chart review to identify documentation of allergies to medications across three sources: (1) nursing records (paper based), (2) physician records (an electronic medical record), and (3) medication order sheets (paper based). Chart review was completed by a trained abstractor blinded to the study aims. The abstractor was a research assistant with over 5 years of ED based administrative experience and 2 years of clinical research experience. Each source was examined for documentation as to whether or not the patient had an allergy to medications and, if so, what details were noted in support of that determination. In addition, data on what medication(s) were ordered were abstracted from the medication order sheet.

Comparative standard (CS) assessment of allergies to medicines

Data on children whose parents completed the CS were reviewed to establish whether an allergy to a specific medication could be determined. If a parent answered “no” to the question “Has your child ever had a problem or reaction to a medicine that they were given?”, that child was considered not to have allergies to medicines. “Yes” or “not sure” answers generated data that were reviewed using an algorithm developed by the consensus of a physician, nurse, and pharmacist team using criteria extracted from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) guidelines regarding hypersensitivity (table 1).12 Two classes of uncertainty were created: (1) general uncertainty wherein parents could not provide enough information to allow for a determination of hypersensitivity‐based or not, and (2) uncertainty between Gell Coombs types I and IV reactions where a parent reported a skin rash but details of the response were mixed as to whether or not the rash was urticarial.

Table 1 Rule set for allergy determination from AAAAI guidelines.

| Type of reaction | Historical data in support of categorization |

|---|---|

| Gell Coombs type I | Any report of: |

| Lip swelling or mouth swelling | |

| Wheezing | |

| Verbal report consistent with hives (“itching”) | |

| Visual identification of hives via photograph | |

| Time frame: Minutes to hours to days after exposure | |

| Gell Coombs type II | Any report of: |

| Problem with blood count | |

| Problem with internal organ such as liver or kidney | |

| Gell Coombs type III | Any report of: |

| Joint swelling or joint soreness | |

| Time frame: Days to weeks after exposure | |

| Gell Coombs type IV | Any report of: |

| Rash not specific to urticarial type | |

| Time frame: Not minutes to hours | |

| Not allergy: intolerance or side effect | Any report of: |

| Nausea or vomiting | |

| Diarrhea | |

| Abdominal pain | |

| More sleepy or tired | |

| More aggressive or acting out | |

| Other neurological symptom | |

| Secondary fungal infection | |

| Not allergy: other | Any report of: |

| Medication failure/therapeutic failure | |

| Parental history of allergy or intolerance | |

| Likely pseudoallergic | Any report of: |

| Type I Gell Coombs reaction in patient exposed to specific agents: opiates, radio contrast media | |

Outcome measures

Errors associated with ED information management were evaluated at five process steps relevant to the allergy history specific to medications: (1) triage assessment of the presence or absence of allergies to medications; (2) treating physician's discussion of the allergy history; (3) treating nurse's discussion of the allergy history; (4) presence of an allergy bracelet and the text encoded on that bracelet; and (5) documentation of the allergy history on medication order sheets. We considered a false positive or false negative report of a medication at triage to be an error. Correct physician based and nurse based actions during history taking were expected to include specific inquiry into the topic of allergies.13 In this institution, a child with a true positive allergy is expected to have an allergy bracelet placed on his/her body at the time of nursing triage that accurately reports the medication(s). Policy does not dictate the extent of detail needed for documentation on the bracelet. Medication order sheets were expected to have accurate documentation of the patient's allergy history if a medication was ordered using the form.

Analysis of data

The CS assessment considered a true allergy to be a medication when the reaction(s) reported by the parent were classified by the algorithm as Gell Coombs I, II, III, IV, or instances where it was uncertain whether a type I or IV existed. Sensitivity and specificity of triage documentation for allergies considered the history based CS and applied algorithm to be the comparative truth. Cases of reported medications where the allergy history remained uncertain due to paucity of data were excluded from further calculation of sensitivity, specificity, or error.

The text of questions asked by triage personnel was reviewed and grouped by content for the subject and objective of each statement. For all data collected from parental interview or chart review, paper based research records were transcribed into an electronic database (Microsoft Access, Redmond, WA, USA). SAS Version 8.1 was used for all analyses (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated as appropriate. 95% confidence intervals were calculated for point estimates of sensitivity and specificity.

Results

We evaluated the information exchange and documentation for allergies to medications over 23 days in summer 2004. Two hundred and fifty six parent‐child dyads arriving for care were observed at triage and then approached to complete the CS; 211 of the 256 parents (82.4%) agreed.

Triage personnel interviewing the parent‐child dyads included both registered nurses (RNs) and clinical nurse assistants. RNs were first to interview the majority of parent‐child dyads (183/256, 71.5%). Most of the parents first spoke in English to the triage personnel (244/256, 95.3%).

Precision of parental report on allergies to medications

During the CS, 49/211 parents (23.3%) gave an answer of “yes” or “not sure” to the question “Has your child ever had a problem or reaction to a medicine that he/she was given?” A total of 63 medicines were reported as potential problems related to allergy. Four medications, reported across three patients, were excluded from further analysis as they represented drugs to which the child had never been exposed. The number of medications reported per child ranged from one to five.

Exact names of medications were successfully communicated for 50/59 (85%) medications. For seven of the nine remaining medicines that were potential problems, parents could report the category and/or class of medication (“antibiotic” and “sulfa”). In two cases parents were unable to identify the category or class of medication. The descriptions offered by the parent were “teeth cleaning medicine” and “shot used to treat fever”.

Classification of parental report of medications that caused problems/reactions

For all 59 medications, judgment as to the type of allergy was made based on historical data supplied by the parent using a rule based schema derived from AAAAI guidelines. Table 2 provides details of this assessment for medications that caused problems or reactions for the child as reported by the parent. In seven of 59 cases (12%) parents believed a reaction was due to allergy, but the guideline based assessment judged the reaction as “not allergy” and consistent with intolerance or side effect. Parents were uncertain about the likelihood of allergy for six cases of medication related reactions; three of these instances were judged to be allergic in nature.

Table 2 Distribution of allergy types based on parental reports.

| Type of reaction | No of medications | % of total medications reported as problematic |

|---|---|---|

| Gell Coombs type I | 21 | 35.6 |

| Gell Coombs type II | 0 | 0 |

| Gell Coombs type III | 1 | 1.7 |

| Gell Coombs type IV | 8 | 13.6 |

| Uncertain type I/ type IV | 8 | 13.6 |

| Not allergy: intolerance or side effect | 16 | 27.1 |

| Not allergy: other | 2 | 3.4 |

| Likely pseudoallergic | 0 | 0 |

| Uncertain: general | 3 | 5.1 |

At the patient level, 49 parental responses of “yes” or “not sure” to the allergy screen were evaluated; one case was not considered further as the child had not been exposed to the medications in question. Of the 48 cases, 28 were positive by the guideline based assessment, 17 were not considered to have an allergy, and three were uncertain due to paucity of data describing the reaction or problem.

Accuracy of triage assessment for allergies

Two hundred and five of 211 triage records were available for review to judge the performance of allergy screening. One of the six missing records was a true positive case with one medication allergy identified by the CS (reducing the number of true positive cases from 28 to 27 for this analysis). Allergies to medications were documented by triage personnel as follows: allergy present in 32/205, negative for allergies in 170/205, and documentation was missing for 3/205 children.

Based on the CS, 27/205 patients had at least one true positive allergy to medications and 178/205 did not have any allergies to medications. The sensitivity of triage personnel's detection and documentation of a true allergy to medication was 74.1% or 20/27 (95% confidence interval (CI) 53.7 to 88.9). The specificity of triage personnel for correctly determining that no allergy to medication existed was 93.2% or 166/178 (95% CI 88.5 to 96.5).

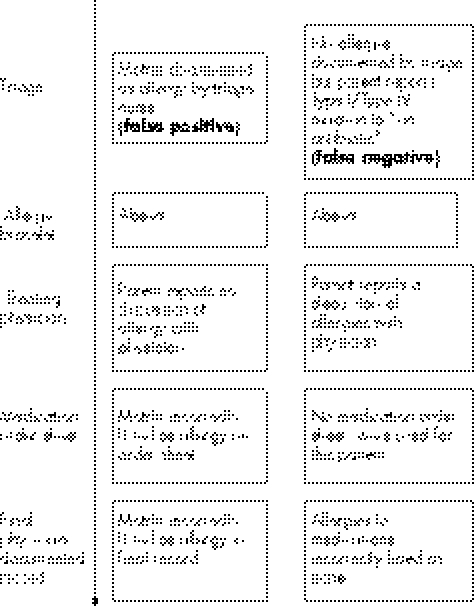

The data were further examined at the level of individual medications. Triage personnel identified and documented a total of 42 medications during the initial interview with the parent‐child dyad. Eleven of the 42 medications (26.2%) were considered false positives by the CS. Triage personnel failed to identify eight of 37 medications (21.6%) judged to be true allergies; these included antibiotic medications such as cefaclor (Ceclor) and amoxicillin, and symptomatic cold relief medication such as Dimetapp (brompheniramine and phenylpropanolamine). Two examples of how incorrect data at triage can persist in the system are shown in fig 1.

Figure 1 How data errors persist.

Follow up ED care by treating registered nurse and doctor

Two hundred and one of 211 parent‐child dyads interacted with the treating physician before CS. A total of 33/200 parents (16.5%) reported “no” (N = 23) or “nor sure” (N = 10) when asked if the treating physician asked about allergies to medications (one incomplete research record). In eight cases, physician interviewers did not inquire about the allergy history when triage data included a false positive or false negative assessment of allergy.

In 44 cases, prior to the CS, the child was administered a medication by ED personnel. Seven of the 44 parents (15.9%) reported “no” (n = 6) or “not sure” (n = 1) when asked if the treating nurse had asked them about allergies to medications. Medications administered in this circumstance included cephalexin, albuterol, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen.

Presence of an allergy bracelet on the child

Of 28 cases where the guideline based assessment judged the child to have an allergy to medication, only 16 (57.1%) were noted to have an allergy bracelet on an extremity. For five children who were wearing an allergy bracelet, the details on the bracelet did not agree with the guideline based assessment information (n = 2) or the bracelet was blank (n = 3). The two patients whose bracelet had incorrect data involved a false positive report of allergy to omeprazole (Prilosec) and a false positive report of a codeine allergy.

Review of medication orders

One hundred and eleven patients in the study cohort had at least one medication ordered during ED care. Of the study participants judged to have a true medication allergy, 5/111 cases (false negative rate 4.5%) were noted to have a medication order sheet where the allergy history was documented as negative (n = 2) or was missing (n = 3). No cases of medication error were noted on the basis of allergy medication mismatch in these five cases.

Triage observations

Triage interrogations on allergies to medications had a range of structures. Table 3 summarizes the types of interrogatory statements observed at triage. All interrogations included the concept of allergy within the body of the question. No question included an explanation or definition of the concept of allergy. The most common interrogatory statement combined an object class reference to “medicine” with the concept of allergy (n = 158).

Table 3 Semantics of triage personnel for allergy based questions.

| Interrogatory examples | Subject type (whom) | Object type (what) |

|---|---|---|

| “Any allergies to medicine(s)?” | General | Specific to medicine |

| “Any known allergies to penicillin, sulfa or latex?” | General | Specific to medicine name |

| “Are you allergic to any food or medication that you know of?” | Specific to parent as subject | Specific to food and medicine |

| “Does he have any allergies to medicine that you know of?” | Specific to child as subject | Specific to medicine |

| “Allergies?” | General | General |

| “Any known food or drug allergies?” | General | Specific to food and medicine |

| “Is she allergic to anything?” | Specific to child | General |

A “yes” answer from the parent to the triage question about allergies was noted for 40/256 respondents. In only 11/40 cases (27.5%) was further clarification sought as to what the actual allergic reaction was to the agent in question.

Discussion

This is the first report of an ED based study that examines the flow of information for critical patient data and its implications for the quality and safety of care. This observational study shows that there are significant gaps in the quality of information management regarding medication allergies in the pediatric ED. We identified errors introduced at triage that persist, despite interactions with subsequent ED clinical providers. Furthermore, we found that parent provided data using a structured verbal interview was superior to allergy information gathered during routine triage assessment.

Poor communication is one of the root causes of medical error and can lead to deficiencies in team and system performance in medicine. Content related communication failures are common.14 How questions are asked of the patient, what content is shared, and how the information provided by the patient is translated into the semantics of medical practice influence the level of accuracy and completeness. The most common question used by nursing staff used the concept of “allergy”. This presumes that all participants in the conversation have the same understanding of what an allergy to a medication actually is. Parents and clinical providers may both vary in their comprehension of this topic. Our observations confirm that parents incorrectly report problems or reactions as allergies when the details of the event do not support a hypersensitivity mechanism.11

Traditional ED care, with the “quick screen” of triage followed by more comprehensive assessment that occurs iteratively over time, does not lend itself to thorough history taking.4 The performance characteristics of nursing triage for accurate identification of medication allergies—with a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 93% at the patient level—suggests that, without subsequent personnel re‐asking and validating triage information, there is a significant risk of error at the decision steps of ordering or prescribing medications. There is also a smaller but important risk of error at the step of administering medications if an initial designation of “no allergies” is incorrect.

Ideal industrial process design for the flow of information in a complex system would never endorse a critical early step where incorrect data were generated at the frequency documented in our observational trial.15 Current ED information management creates proximal data errors and then must rely on downstream error correction to ensure safety. However, as documented in our study, subsequent lapses in performance by individual providers allow errors to persist that pose a risk to the patient. Parental reports of clinical providers' actions suggest that, in 10–25% of cases, no additional allergy history was solicited or reviewed by either the physician or nurse. These interrelated and error prone steps can lead to patient harm.16 Although our study did not document any medication errors that reached the patient, we believe this is simply a matter of a limited number of subjects and chance itself.

The question for system redesign is: how can an ED system gather critical data on allergies and current medications quickly and accurately within the existing throughput model of rapid triage and subsequent iterative care? Some authors have promoted technology as part of the solution to the complexities of data management.17,18,19,20 A high performing clinical microsystem includes “integration of technology into workflow” as one of eight important dimensions.21 However, pulling data out of existing paper or electronic records may not solve the problem of data accuracy. Both paper and electronic strategies for documentation have inherent limitations and biases to their ability to assist a human clinician in creating an accurate and complete record. Inpatient records for pediatric patients have been shown to have a false positive allergy report rate of up to 30%.22 An adult tertiary care hospital considered a leader in computerized provider order entry systems reported that one third of allergy alert overrides were explained by an incorrect allergy history in the electronic database.23

Key messages

There are significant gaps in the quality of information management regarding medication allergies in the pediatric emergency department.

Elimination of this risk will probably require a more structured approach to capturing the allergy history and a systematic method of both validating and integrating allergy specific data into the medication delivery process.

Current ED practice creates an allergy history that contains gaps in data quality at initial triage that persist through the system and create the potential for harm. Elimination of this risk will require a more structured approach to the asking and clarifying of the allergy history, a strategy also shown to be successful as a pharmacist led effort for inpatient care.24,25 Potential solutions may focus on the clinical provider or look to the patient to take a more active role in maintaining his/her own safety.26 Provider focused solutions might include creating standard scripts for nurses to use in their allergy specific communication or forcing the provider to enter more detail for critical data at the point of documentation. Patient focused solutions might include implementing a technology based mechanism for patients to enter allergy specific data directly for subsequent discussion with the treating nurse and physician. Within the ED setting, decisions about how much time a triage nurse should spend interviewing the patient and the timing of any patient driven data capture within the care process are important unresolved issues.

Specific limitations may have affected our results. They may not be generalizable to other institutions where the ED population or the ED workflow varies from the single site used for this work. Although we implemented a protocol to survey consecutive patients, we cannot exclude the possibility of enrolment bias, given that nearly 20% of parents did not wish to be interviewed. The comparative standard interview developed for this work, although based on the AAAAI guideline and developed by a multidisciplinary team, was not formally validated prior to its use. Certain aspects of system performance were based on the recall of parents and thus are subject to bias; however, as the interview between the research assistant and the parent occurred soon after the events in question, this bias is expected to be minimal. The low number of Spanish speaking patients in our sample impeded investigation of language specific barriers that may create additional information gaps.

Full details of the structured verbal interview with the parents are given in the Addendum available online at http://www.qshc.com/supplemental.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Ms Sofia Warner to the completion of this project.

Footnotes

Dr Porter was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS11660). The project was also supported by a grant from the Department of Medicine, Children's Hospital Boston.

Competing interests: none declared.

The project was conceived and executed as a quality improvement project focused on system performance, with the goal of improving care with regard to medication safety. The Committee on Clinical Investigation at Children's Hospital Boston does not consider projects that are designed to improve clinical care to better conform to standards as research requiring formal review, provided that participants' data remain anonymous. We solicited verbal permission from parents to complete the in‐person interview.

Full details of the structured verbal interview with the parents are given in the Addendum available online at http://www.qshc.com/supplemental.

References

- 1.Nelson E C, Batalden P B, Homa K.et al Microsystems in health care: Part 2. Creating a rich information environment. Jt Comm J Qual Saf 2003295–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety Patient safety: achieving a new standard of care. Washington, DC: National Academic Press, 20041–66.

- 3.Patient Safety Task Force Patient safety in the emergency department environment. American College of Emergency Physicians, 2001. Available at http://www.acep.org/download.cfm?resource = 493 (accessed 31 March 2004)

- 4.Knopp R, Rosenzweig S, Bernstein E.et al Physician‐patient communication in the emergency department. Part 1. Acad Emerg Med 199631065–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crain E F, Mortimer K M, Bauman L J.et al Pediatric asthma care in the emergency department: measuring the quality of history‐taking and discharge planning. J Asthma 199936129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 200139–62. [PubMed]

- 7.Rhodes K V, Lauderdale D S, He T.et al “Between me and the computer”: increased detection of intimate partner violence using a computer questionnaire. Ann Emerg Med 200240476–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter S C, Mandl K D. Data quality and the electronic medical record: a role for direct parental data entry. Proc AMIA Symp 19991–2354–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter S C, Cai Z, Gribbons W.et al The asthma kiosk: a patient‐centered technology for collaborative decision support in the emergency department. JAMIA 200411458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter S C, Kohane I S, Goldmann D A. Parents as partners in obtaining the medication history. JAMIA 200512299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantrill J A, Cottrell W N. Accuracy of drug allergy documentation. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm 1997541627–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, and the Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Executive summary of disease management of drug hypersensitivity: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 199983665–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollack D A, for the DEEDS Writing Committee Data Elements for Emergency Department Systems, Release 1. 0 (DEEDS): a summary report, Ann Emerg Med 199831264–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingard L, Espin S, Whyte S.et al Communication failures in the operating room: an observational classification of recurrent types and effects. Qual Saf Health Care 200413330–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elson R B, Faughnan J G, Connelly D P. An industrial process view of information delivery to support clinical decision making: implication and systems design and process measures. JAMIA 19974266–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reason J. Understanding adverse events: human factors. Qual Health Care 1995480–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried C F, Handler J A, Smith M S.et al Clinical information systems: instant ubiquitous clinical data for error reduction and improved clinical outcomes. Acad Emerg Med 2004111162–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teich J M. The benefits of sharing clinical information. Ann Emerg Med 199831274–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teich J M. Information systems support for emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 199831304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson S J, Zwemer F L, Nathanson L A.et al Where's the beef? The promise and the reality of clinical documentation. Acad Emerg Med 2004111127–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohr J, Batalden P, Barach P. Integrating patient safety into the clinical microsystem. Qual Saf Health Care 20041334–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouwmeester M C, Laberge N, Bussieres J F.et al Program to remove incorrect allergy documentation in pediatrics medical records. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm 2001581722–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh T C, Kuperman G J, Jaggi T.et al Characteristics and consequences of drug allergy alert overrides in a computerized physician order entry system. JAMIA 200411482–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plizer J D, Burke T G, Mutnick A H. Drug allergy assessment at a university hospital and clinic. Am J Health‐Syst Pharm 1996532970–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fertleman M, Barnett N, Patel T. Improving medication management for patients: the effect of a pharmacist on post‐admission ward rounds. Qual Saf Health Care 200514207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent C A, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care 20021176–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]