Abstract

It has been proposed that formalisation of training to encompass prehospital and retrieval medicine should be considered in the UK, using those currently involved in immediate care as the core providers of these services.1 Although there is an overlap in some aspects of “prehospital” and “retrieval” medicine, there are some distinct differences, both in terms of the skill base and service provision required. Retrieval medicine is the term used to indicate the use of an expert team to assess, stabilise and transport patients with severe injury or critical illness. Implicit in this process is the early provision of specialised advice to the health providers at the patient's side. In the UK, there is currently no national and often no regional strategy to coordinate the provision of secondary retrieval services for critically ill patients. International models do exist, which may be of help in this respect.

This is the first of two articles reviewing the retrieval process both from a clinical and service delivery perspective.

Overview

The realisation by paediatricians and neonatologists that teams are needed to attend and stabilise the sickest children,2,3,4 combined with the centralisation of specialist services, has led to the development of children's retrieval services in all the centres in the UK. Unfortunately, the same has not been true for adult services in the UK, unlike in other developed countries, most notably Australia, where geography has driven the development of retrieval medical services. Retrieval medicine as a subspecialty of emergency medicine, anaesthesia and intensive care exists in Australasia, integrated with both prehospital care and hospital‐based critical care services. The requirement for training is normally a 6‐month dedicated module at pre‐consultant level. Sydney has a highly developed emergency response system for the treatment and transport of seriously ill and injured patients. Overall, the system has at its disposal three helicopters, four fixed‐wing aircraft, two adult intensive care road ambulances and three paediatric/neonatal intensive care road ambulances. It is an integrated regional system, with a state medical co‐ordinator and a centralised ambulance control centre constantly reviewing medical retrieval work statewide and tasking the various organisations involved as requests are made. This service is available to all New South Wales hospitals and health districts via a 24‐hour free‐phone number.5

Retrieval medicine is the concept of combining transfer from one medical institution to another that is able to provide a higher level of care. Accepting the principle that the aim is to transfer a patient from a lower level of care to a higher level, a condition is then that such transfer should be effected without suffering a reduction in care during transit. The level of transport care should thus be matched to the severity of the patient's condition. As such, the rigid adherence to a particular skill mix of the attendants may be restrictive. Services with different models have produced data relating to their own patient cohorts. A 12‐year study (1984–95) based in South Australia, involving 4443 transfers of critically ill patients (819 by road (mean 71 km), 808 by helicopter (mean 122 km) and 2777 by fixed wing (mean 398 km)) showed 2.5% deaths during transport, only one of which was deemed preventable on review.6 A large retrospective study of over 3000 patient records in a large tertiary referral intensive care unit in New Zealand that had 16% of its admissions via transferred patients (most by air) showed lower standardised mortality ratios in patients with sepsis, respiratory disease and intracranial haemorrhage. The standardised mortality ratios for patients with major trauma were similar in transported and non‐transported patients.7 Other services in Australasia have monitored the effect of transfer of critically ill patients in a metropolitan environment for non‐clinical reasons. Of 73 consecutive transfers in this category, although there was a delay in admission and increased length of stay, there was no overall increase in mortality in the transferred group.8

There has also been an acknowledgment, however, that given the cost‐intensive nature and high specialist skill base of these systems, the available scientific data are still quite insufficient.9

Box 1: Adult learning principles underpinning the syllabus of the Inter‐Collegiate Board for Training in Intensive Care Medicine in transport care (IBTICM Curriculum section 7(f))

-

Knowledge

-

-

Principles of safe transfer of patients

-

-

Understanding of portable monitoring systems

-

-

-

Skills

-

-

Intrahospital transfer of patients requiring ventilatory support

-

-

Interhospital transfer of patients with single‐organ or multiple‐organ failure

-

-

-

Attitudes

-

-

Insistence on stabilisation before transfer

-

-

Pre‐transfer checking of kit and personnel

-

-

Planning for and prevention of problems during transfer

-

-

Communication with referring and receiving institutions and teams

-

-

Insistence on adequate support from senior/more experienced colleagues

-

-

-

Training objectives

-

-

Supervised intrahospital transfers of ventilated patients to theatre or for diagnostic procedures

-

-

Interhospital transfers of ventilated patients with or without support of other organ systems

-

-

It is often incorrectly considered that secondary retrieval missions are always less urgent than primary missions, but experience has shown that secondary retrievals are often time critical owing to an insufficient level of care at the referring facility. The aim of patient transport is to enhance the quality of patient care and provide equity of access to specialist services to all those patients located within a given geographical location, to improve the outcome in cases of critical illness or traumatic injury. A recently formed service in Scotland, designed to deliver critical care to a geographically remote area, appears to have had early success in filling an unmet need. This appears to be the first dedicated retrieval service in the UK, integrating tertiary hospital specialists with community hospitals and the emergency services. It will be interesting to see if this receives long‐term support and funding.10

The transfer period itself has been shown to be one of the most critical phases in any episode of critical care; therefore, there must be a local strategy in place for management of the process, with services such that safe and efficient coordination can take place on a 24‐h basis. A published audit of over 1000 patients in the north‐west region showed clinically relevant cardiovascular events in 5% and equipment failures in about 4%.11

The retrieval process in the UK

The frequency of transfers of the critically ill is on the increase in the UK owing to

an increase in the demand for level 2 and 3 beds

improved resuscitation and surgical techniques

increased expectation.

Critically ill patients may require transportation within or outside their receiving hospital, to facilitate investigation or treatment, for the provision of specialist services, in response to the lack of an available higher‐level care bed in the referring hospital or for repatriation.

Guidelines have existed in the UK for 15 years regarding the medical use of aircraft and helicopters for patient transfer.12,13 Concern in the past, over the transfer of patients with head injury to regional neurosurgical centres14 and some well‐publicised cases, has led to the development of the Intensive Care Society guidelines for the transfer of the critically ill adult (2002).15 These are quite specific when detailing the expectation on the transferring medical personnel.

“Personnel involved in the transport of critically ill patients have a responsibility to ensure that they are adequately trained and experienced.” In regard to training, they are equally specific.

“Competency based training and assessment should be developed to ensure the highest possible standards of care for the critically ill patient requiring transport”. Unfortunately, the guidelines are not clear on how these expectations can be met in the current UK system. There are numerous issues relating to training, personal safety and clinical governance, which remain unresolved in many hospitals involved in the transfer of the critically ill in the UK. Both the USA and Australasia have well‐developed retrieval services and have published their own guidelines in relation to transport of the critically ill.16,17

The inter‐collegiate board for training in intensive care medicine has highlighted the adult learning principles underpinning transport care within its syllabus (box 1).

Box 2: Preparation for transfer

Respiration

Circulation

Head

Other systems

Monitoring

Line placement and securing

Investigations

Notes and x rays

Transportation

Destination

The effect of an adult retrieval service specifically designed to serve district hospitals in the UK and stabilise patients before transfer to a specialist centre has been shown by a road‐based service in London.18 Of 259 transfers of critically ill patients (168 by a retrieval team and 91 by the referring hospital), there was considerably more acidosis, hypotension and early mortality in the group transferred by a non‐specialist team.

Audit has shown that, despite the progress made in the UK, many patients are still not managed satisfactorily and there is poor adherence to guidelines. Often, junior medical staff, with poor levels of supervised training, are left dealing with critically ill patients during transfer.19

The Safe Transfer and Retrieval course20 has developed a training system based on assessment, control, communication, evaluation, preparation and packaging, transportation methodology. It is worth considering these in relation to the current clinical delivery of care to transported, critically ill patients.

Assessment

In general, critically ill patients tolerate transportation poorly, with evidence suggesting that hypoxia and hypotension may ensue in at least 15% of cases and that these deleterious effects may continue for several hours after arrival at the receiving hospital.21 Meticulous preparation must be undertaken for such hazards to be minimised and for uneventful patient transfer to ensue.

Control and communication

These are vital elements in the transfer process. Early communication with receiving departments, whether in your own or another hospital, is vital. Identifying a senior responsible clinician at each location is a priority. Communication during transfer may be reliant on the ambulance radio, but mobile phones are a useful adjunct. Even in seemingly well‐organised systems of patient retrieval, wide variations can exist in terms of the time taken to organise teams to attend or find an accepting unit for the patient to be ultimately cared in. One hospital in Victoria reported a range of 33–373 min for patients remaining in the emergency department before retrieval and an average of over four phone calls to get the patient accepted in a larger centre, despite having a centralised referral service.22

Transport mode

Several different factors influence the choice of transport mode. These factors include the availability of appropriate vehicles and the distance to be travelled, the time of day, the terrain, the logistics of various transport modes, the status of the patient, training of retrieval team members, and local weather and geography. The principal advantage of a ground ambulance is its ready availability, even in remote and rural areas. Moreover, air ambulances carry a greater risk of injury for the crew than road ambulances. It is obviously undesirable to be in the back of a road ambulance for 150 km, and the advantages of transferring by air may outweigh the stresses of the transfer by land. A Scandinavian service, which transfers patients by road over long distances, often because of adverse flying conditions, has reported on 66 patients with considerable respiratory and cardiovascular compromise transferred a mean distance of 161 (120–460) km by road. In all, 14 (21%) patients were transferred prone and 59 (89%) patients had ionotropic support running for the journey. No excess mortality was observed in this group.23

Preparation and packaging for transfer

All personnel should familiarise themselves with the patient and the current treatment. As with the planning phase, it is useful to have a checklist to avoid omissions (box 2).

A full clinical examination with reference to ongoing monitoring should be carried out. Respiratory support is fundamental. Intubation during transfer is difficult and hazardous; if any doubts exist about respiratory function, intubation and mechanical ventilation must be carried out before transport.

Transportation and monitoring

Basic minimum standards of monitoring for critically ill patients need to be followed during transport. These have been recently reviewed and updated with regard to patients with brain injury in the UK.24

The continuous presence of appropriately trained staff (including the incorporation of consultant cover for training‐grade medical staff working alone)

Echocardiogram

Invasive blood pressure

Arterial oxygen saturation

Capnography

Temperature (preferably core and peripheral)

Urinary output by urinary catheter

Central venous pressure monitoring where indicated.

The standard of monitoring should approach that expected in the hospital setting. This principle has been established for some time and pre‐dates all the current guidelines.25

Box 3: Troubleshooting during transfer

-

Common physiological changes

-

-

Hypoxia

-

-

Cardiac arrhythmia

-

-

Hypotension

-

-

Decrease in Glasscocomascale

-

-

Hypothermia

-

-

Hypoglycaemia

-

-

-

Common equipment problems

-

-

Exhaustion of oxygen supply

-

-

Ventilator malfunction

-

-

Loss of monitoring

-

-

Loss of intravenous access

-

-

Accidental extubation

-

-

Tracheal tube blockage

-

-

Equipment

Equipment must be suited to the environment—that is, it should be durable and lightweight and have sufficient battery life. A monitored oxygen supply with a safety margin of 2 h on the transfer time is essential. There should be storage space for equipment and staff should be appropriately clothed.

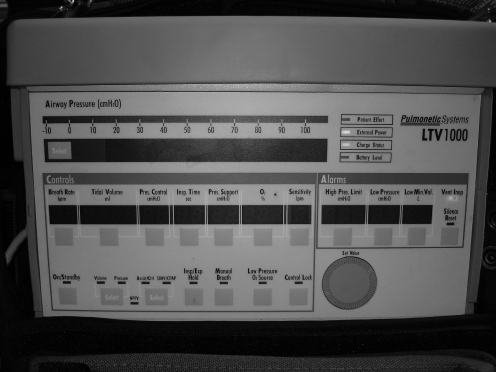

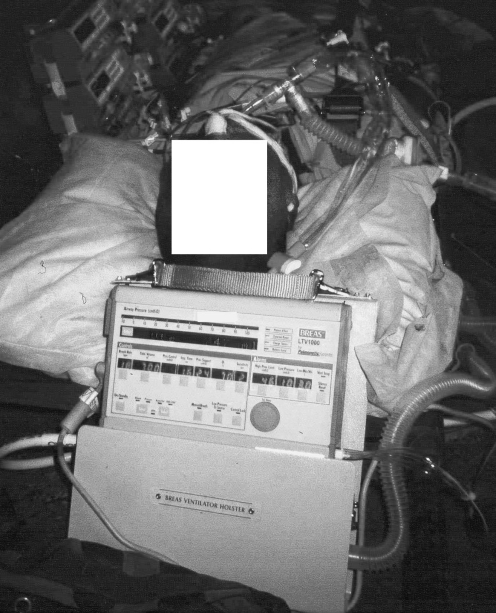

A battery‐powered portable ventilator, with disconnection and high‐pressure alarms and the ability to provide PEEP and variable FiO2, I: E ratio, respiratory rate and tidal volume, as well as the ability to provide a range of ventilation modes (pressure and volume ventilation) is required. Both the Drager Oxylog 3000 (Drager Medical UK, Hemel Hempstead, UK) and Breas LTV 1000 (Breas Medical AB, Molnlycke, Sweden) provide these capabilities (figs 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Breas LTV 1000 ventilator.

Figure 2 Braes LTV 1000 used for ventilation during transfer.

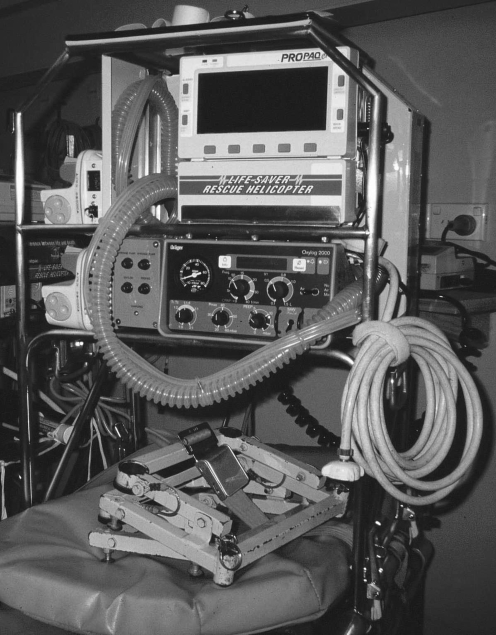

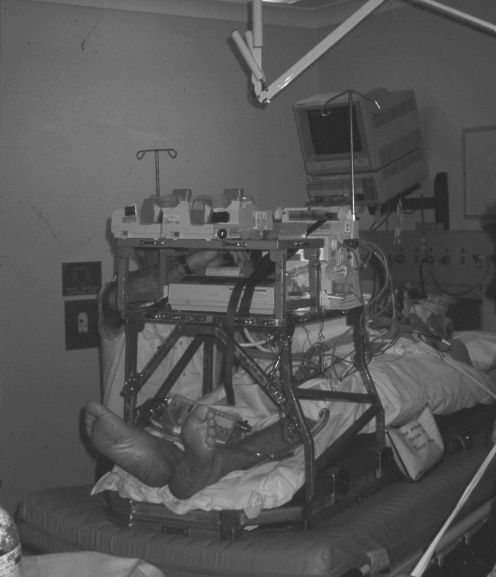

Reliance on gas‐powered portable ventilators, with an inability to deliver variable oxygen concentrations or modes of ventilation, should be considered unacceptable for retrieval work.26 A dedicated equipment bridge, containing ventilator, monitoring equipment and infusion devices, is becoming the method of choice for providing these requirements. Developments in other countries have made these widely available, but there has been reluctance in the UK to embrace this purpose‐built technology27 (figs 3 and 4).

Figure 3 Stretcher bridge ventilator, monitoral syringe drivers incorporated.

Figure 4 Stretch bridge in‐situ.

Box 4: Final checklist and handover format

Checklist

Airway and nasogastric tube

Breathing and end‐tidal carbon dioxide

Circulation and invasive monitoring

Disability/cervical collar and head injury care

Exposed and examined

Family informed

-

Final considerations

-

-

Ask for notes and x rays?

-

-

Bed confirmed?

-

-

Continuity of care assured?

-

-

Drugs and spares?/documentation

-

-

Everything secure?

-

-

-

Handover

-

-

Acute problem

-

-

Before admission to intensive care unit

-

-

Current clinical condition

-

-

Drugs/infusions and documentation

-

-

Examination and any problems during transport

-

-

Family

-

-

Box 5: Summary principles for safe critically ill patient transfers

1. Identify hospitals in network

Local list with telephone numbers

-

Specialist list with telephone numbers

-

-

Cardiothoracic

-

-

Neurosurgical

-

-

Paediatric

-

-

2. Identify transport mode

Consultant authorising transfer

Consultant authorising reception

Nursing/paramedical escorts

Ambulance authorisation

Weather conditions suitable

3. Identify kit

Ventilator and power lead

Portable monitor and power lead

Syringe drivers

Power inverter/adapter and spare batteries

Transfer bag

Drugs bag

Oxygen and self‐inflating bag

Stretcher type/stretcher bridge

Personnel and portering

Notes and x rays

Documentation/audit form

4. Identify personnel

-

Core specialty experience

-

-

Airway management

-

-

Ionotropes

-

-

Head injuries and trauma

-

-

Paediatrics

-

-

-

Familiarity with kit

-

-

Ventilator

-

-

Drugs

-

-

Syringe drivers

-

-

Monitor

-

-

Transducers

-

-

Defibrillator/external pacer

-

-

Interhospital management

Despite good preparation, interventions may need to be carried out en route; this may involve stopping the vehicle if transport is by road. Once patients are secured on transfer stretchers and monitoring equipment is attached, it is difficult to gain good access for continued treatment. European workers have used a dedicated scoring system to indicate those patients prone to develop major complications en route. The Risk Score for Transport Patients was applied to 128 interhospital critically ill transfers in Greece. The scoring system was able to predict those patients who were likely to develop complications during transit, based on an 11‐question discriminator. However, the Risk Score for Transport Patients was not able to reliably predict long‐term mortality in these patients.28 It may be necessary to stop land ambulances if urgent treatment becomes necessary; some troubleshooting may be needed during the trip (box 3).

Travelling in vehicles at high speed is hazardous; therefore, all staff in the vehicle must follow the instructions of the crew. The team should ensure that all equipment is secured to the transfer trolley and should be trained in securing and using this equipment.

Data on the relative risk of ambulance transport has shown that restrained occupants are less likely to be killed or seriously injured than unrestrained occupants. Recommendations from this are that all staff should wear seatbelts and that family members should travel in the front seats.29

Documentation, including incident and audit forms, must be completed as soon as practicable after the transfer has taken place. There should be a clear continuum of care from the decision to move patients until (and including) their arrival at the receiving centre (box 4).

Discussion

Despite the availability of published guidelines, standard approaches to transport care in the UK still appear some way off. The skills and competencies required for this work have some overlap with pre‐hospital care, but are by no means interchangeable. Most transfers of critically ill patients occur within hospitals as patients are moved between different departments for treatment and investigation. It may be that this is an unrecognised resource in terms of providing training and education, in a relatively protected environment for staff expected to work with such patients in the out‐of‐hospital environment.30 There are other advantages of having well‐trained teams with a variety of skills; they can be used in crisis management situations. This was well demonstrated in Australia, which was able to respond relatively quickly to the Bali bombings.

Teams were sent to Bali itself, whereas other teams within Australia assembled at Darwin to receive repatriated casualties, stabilise and then transfer to burns units elsewhere.31 Similarly, the German government was able to provide a team of 30 emergency doctors and paramedics to assess victims of the 2004 Asian tsunami and to assist in repatriating almost 3000 (2500 minor injuries; 300 moderate to severe injuries) foreign casualties. Three airlifts using two medically equipped aircraft of the German Air Force evacuated 134 moderate to severely injured from the disaster area.32 The movement of patients around London after the events of 7 July 2005 also required pre‐hospital and retrieval skills, both for those injured in the incident and for those requiring movement subsequently between hospitals.33

Decisions about appropriate emergent transportation will be driven by the best available knowledge at the time of the patient's clinical needs. This will have to be balanced against the inherent safety of the operation, welfare of the patient, quality of care available in transit and the economics of providing transportation at this particular level. Obviously, no decision can be made in isolation and, where appropriate services are not available, it simply may not be possible to make the most cost‐effective decisions in the interest of the patient. Local training and adherence to local, as well as national, guidelines should go some way to achieving more uniform patterns of care. The concept of “transit care medicine” has been suggested previously34 and is useful when considering this patient group and the variety of skills required to deliver effective transport and ongoing therapeutic interventions. A national reporting system for adverse incidents occurring during transport would go some way in seeing what the situation is nationwide. This has been successful in Australia, and is considered an important part of ensuring both patient and staff safety.35 It would also provide a focus for how systems could be developed in the future in the UK to provide for this nationally under‐resourced service (box 5).

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mackenzie R, Bevan D. For debate. A licence to practise pre‐hospital and retrieval medicine. EMJ 200522286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britto J, Nadel S, Maconichiel et al Morbidity and severity of illness during interhospital transfer: impact of a specialised paediatric retrieval team. BMJ 1995311836–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ege W E, Kanter R K, Weigle C G.et al Reduction of morbidity in interhospital transport by specialised paediatric staff. Crit Care Med 1994221186–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henning R. Emergency transport of critically ill children: stabilisation before departure. Med J Aust 200315766–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirley P J, Klein A A. Sydney Aeromedical Retrieval Service. Pre‐Hospi Immediate Care 19993233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilligan J E, Griggs W M, Jelly M T.et al Mobile intensive care services in rural South Australia. Med J Aust 1999171617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flabouris A. Patient referral and transportation to a regional tertiary ICU: patient demographics, severity of illness and outcome comparison with non‐transported patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 199927385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duke G J, Green J V. Outcome of critically ill patients undergoing interhospital transfer. MJA 2001174122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koppenberg J, Taeger K. Interhospital transport: transport of critically ill patients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 200215211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AS. Hsu R, Corfield A R.et al Establishing a rural emergency medical retrieval service. EMJ 20052376–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maccartney I, Nightingale P. Transfer of the critically ill adult patient. Br J Anaesth [CEPD Rev] 2001112–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Working Party Report Medical helicopter systems‐ recommended minimum standards for patient management. J Roy Soc Med 199184242–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Working Party Report Recommended standards for UK fixed wing medical air transport systems and for patient management during transfer by fixed‐wing aircraft. J Roy Soc Med 199285767–771. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Neuroanaesthesia Society of Great Britain and Ireland and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Recommendations for the transfer of patients with head injuries to neurosurgical units 1996

- 15.Intensive Care Society, UK Guidelines for the transport of the critically ill. 2002. www.ics.ac.uk (accessed 14 Sep 2006)

- 16.Warren J, Fromm R E, Orr R A.et al Guidelines for the inter‐ and intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 200432256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faculty of Intensive Care of the Australian and New Zealand College Of Anaesthetists and Australasian College for Emergency Medicine Minimum standards for transport of the critically ill 2003 [PubMed]

- 18.Bellingen G, Olivier T, Batson S.et al Comparison of a specialist retrieval team with current United Kingdom practice for the transport of the critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 200026740–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Easby J, Clarke F C, Bonner S.et al Secondary inter‐hospital transfers of critically ill patients: completing the audit cycle. Br J Anaesth 200289354 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Advanced Life Support Group Safe Transfer and Retrieval: The Practical Approach. London: BMJ Books, 2002, (ISBN 0 7279 1583 5)

- 21.M, Bion J E. Transporting critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 199521781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig S S. Challenges in arranging interhospital transfers from a small regional hospital: an observational study. Emerg Med Australasia 200517124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uosaro A, Parvianen I, Takala J.et al Safe long‐distance interhospital ground transfer of critically ill patients with acute severe unstable respiratory and circulatory failure. Intensive Care Med 2002281122–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland Recommendations for the safe transfer of patients with brain injury 2006

- 25.Oakley P A. The need for standards in inter‐hospital transfer [editorial]. Anaesthesia 199449565–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClusky A, Gwinnutt C L, Hardy L.et al Evaluation of the Pneupac Ventipac portable ventilator in critically ill patients. Anaesthesia 2001561073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagappan R, Riddell T, Barker J.et al Patient care bridge—mobile ICU for transit care of the critically ill. Anaesth Int Care 200028684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markakis C, Dalezios M, Chatzicostas C.et al Evaluation of a risk score for interhospital transport of critically ill patients. Emerg Med J 200623313–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker L R, Zaloshnja E, Levick N.et al Relative risk of injury and death in ambulances and other emergency vehicles. Accid Anal Prev 200335941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shirley P J, Bion J. Intra‐hospital transport of critically ill patients: minimising risk. Intensive Care Med 2004301508–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran M D, Garner A A, Morrison I.et al The Bali bombing: civilian aeromedical evacuation. MJA 2003179353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maegele M, Gregor S, Steinhausen E.et al The long distance tertiary air transfer and care of tsunami victims: injury pattern and microbiological and psychological aspects. Crit Care Med 2005331136–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shirley P J. Critical care delivery: the experience of a civilian attack. J R Army Med Corps 200615217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagappan R. Transit care medicine‐ a critical link. Crit Care Med 200432305–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Australian Patient Safety Foundation Australian Incident Monitoring Study (Retrieval Medicine). Adelaide, SA 1999