Abstract

Craniosynostosis is a congenital developmental disorder involving premature fusion of cranial sutures, which results in an abnormal shape of the skull. Significant progress in understanding the molecular basis of this phenotype has been made for a small number of syndromic craniosynostosis forms. Nevertheless, in the majority of the ∼100 craniosynostosis syndromes and in non‐syndromic craniosynostosis the underlying gene defects and pathomechanisms are unknown. Here we report on a male infant presenting at birth with brachycephaly, proptosis, midfacial hypoplasia, and low set ears. Three dimensional cranial computer tomography showed fusion of the lambdoid sutures and distal part of the sagittal suture with a gaping anterior fontanelle. Mutations in the genes for FGFR2 and FGFR3 were excluded. Standard chromosome analysis revealed a de novo balanced translocation t(9;11)(q33;p15). The breakpoint on chromosome 11p15 disrupts the SOX6 gene, known to be involved in skeletal growth and differentiation processes. SOX6 mutation screening of another 104 craniosynostosis patients revealed one missense mutation leading to the exchange of a highly conserved amino acid (p.D68N) in a single patient and his reportedly healthy mother. The breakpoint on chromosome 9 is located in a region without any known or predicted genes but, interestingly, disrupts patches of evolutionarily highly conserved non‐genic sequences and may thus led to dysregulation of flanking genes on chromosome 9 or 11 involved in skull vault development. The present case is one of the very rare reports of an apparently balanced translocation in a patient with syndromic craniosynostosis, and reveals novel candidate genes for craniosynostoses and cranial suture formation.

Keywords: craniosynostosis, SOX6, translocation, conserved non‐genic sequences

Craniosynostosis is the premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures and is a relatively common birth defect with a prevalence of 1 per 2100–3200 births.1 The aetiology of craniosynostosis is heterogenous and it often occurs as an isolated feature (non‐syndromic), although it can also be associated with other malformations as is the case in about 100, mostly autosomal dominant, syndromes.2 Clinically, the premature fusion of calvarial bones variably results in cranial and facial asymmetry, brachycephaly or turricephaly, mid‐face hypoplasia, hypertelorism with exorbitism, and, depending on the timing and type of affected sutures, neurological complications.

Current knowledge on the pathomechanisms of craniosynostosis and suture biology is mainly based on the identification of genes and gene defects in a few autosomal dominant craniosynostosis syndromes. Dominant negative mutations, causing a ligand independent activation of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1–3 have been found in several conditions, including Pfeiffer, Crouzon, Jackson‐Weiss, Apert, and Muenke syndromes.2,3 Mutations in the MSX2 gene, encoding a homeobox transcription factor, were identified in a family with Boston‐type craniosynostosis, and loss of function mutations in the transcription factor gene TWIST were identified in a subset of patients with Saethre‐Chotzen syndrome.2,3 However, the molecular basis of many syndromic craniosynostosis forms is still unknown. This also applies to non‐syndromic craniosynostoses, which are sporadic in most cases, account for approximately 80% of all craniosynostoses, and involve both environmental and genetic risk factors (reviewed by Cohen1). Thus, the identification of novel candidate genes is of major importance for the molecular understanding of the aetiology and pathomechanisms of these disorders.

Here we report on a male infant with a de novo balanced translocation t(9;11)(q33;p15) and a complex craniofacial dysostosis, including craniosynostosis and distinct facial features. Cloning of both breakpoint regions revealed that the translocation disrupts the SOX6 gene on chromosome 11p15, and a region on chromosome 9 with a large number of highly conserved non‐genic sequences (CNGs). This is one of the very rare reports of an apparently balanced translocation in a patient with syndromic craniosynostosis. The present study adds novel genes to the current list of candidate genes that may be involved in craniosynostoses and cranial suture formation in general.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient

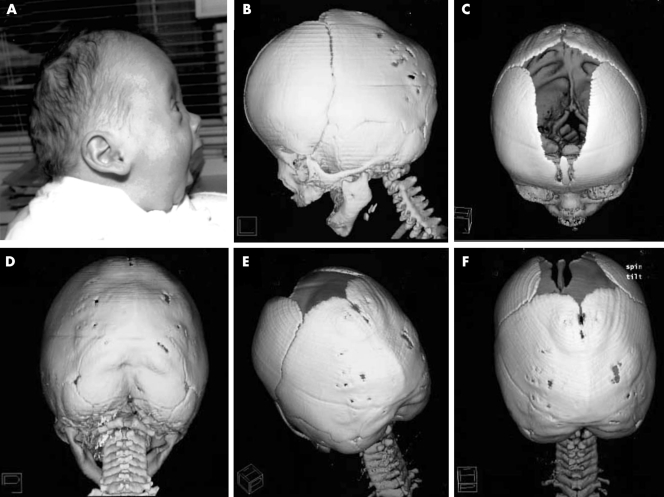

The patient was born after an uneventful pregnancy to non‐consanguineous parents (31 year old mother and 38 year old father) of German origin. At birth (week 38+3), length was 510 mm (50th centile), weight 2670 g (<10th centile), and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) 330 mm (just above 10th centile). The child presented with a flat midface, flat supraorbital ridges, a high forehead, downslanting palpebral fissures, low set and posteriorly rotated ears, a wide anterior fontanelle, and muscular hypotonia. There were no associated features of the hands or feet such as syndactyly, brachydactyly, or broad first rays. The suspicion of bilateral lambdoid and posterior sagittal craniosynostosis was supported radiographically (fig 1). Results of brain, cardiac, and renal ultrasound studies, of routine neonatal laboratory screening including thyroid function, and of eye and ear examination gave normal results. A conventional cytogenetic analysis on G‐banded metaphases from peripheral lymphocytes of the patient and his parents revealed the karyotype 46,XY,t(9;11)(q33;p15) de novo in the patient. Successful release surgery of the lambdoid and posterior sagittal suture was performed at the age of 5.5 months.

Figure 1 Patient. (A) Profile of patient illustrating flat midface, mildly protruding eyes, high forehead, and low set, posteriorly rotated ears mimicking a Crouzon‐like profile. (B–F) Cranial spiral CT scans at 3.5 months of age. Note fusion of the lambdoid sutures and of the occipital part of the sagittal suture with external ridging. Written consent was obtained from the patient's legal guardians for publication of these clinical photographs.

The anthropometric data remained within the normal range; at 5.5 years of age, length was 1.07 m (10th centile and within parental target centile range), weight 17 kg (25th centile), and OFC 510 mm (25th–50th centile). There was mild developmental speech delay (on average five word sentences, attending normal kindergarten with 1 additional hour per week for speech therapy). Repeated hearing examinations have yielded normal results. Family history and parental examination were unremarkable with respect to craniosynostosis or other skeletal features.

In order to exclude mutations in the two genes known to be mutated in Crouzon syndrome we screened the complete coding sequence of the FGFR2 and FGFR3 genes. No mutation was found which could account for the phenotype (data not shown). In addition, we excluded the P252R mutation in the FGFR1 gene.

Cytogenetic and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) studies

Cytogenetic analysis was conducted on G‐banded chromosomes of cultured peripheral blood lymphocytes. Initial FISH experiments were performed with yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) clones from the regions of interest. Fine mapping of breakpoints was performed with smaller bacterial and plasmid (BAC and PAC) clones. DNA samples were prepared according to standard protocols and were labelled with either biotin‐16‐dUTP or digoxigenin‐11‐dUTP by nick translation. Immunocytochemical detection of probes was performed as described elsewhere.4 Chromosomes were counterstained with 4′6‐diamino‐2‐phenyl‐indole (DAPI). Metaphases were analysed with a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope.

Molecular investigations

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes. For mutation screening, all 18 coding exons of the FGFR2 and FGFR3 genes were amplified by PCR using intronic primers from FGFR2 (sequences available on request) and FGFR3.5 Direct cycle sequencing was carried out by using a commercial kit and automatic sequencers (Big Dye Terminator sequencing kit on an ABI377 and an ABI3730 automatic sequencer; all Perkin Elmer) with gene specific primers. PCR amplification and Southern blot analysis were performed according to standard protocols. As probes for the Southern blot analysis we used three different PCR fragments, of 417 bp (probe 1; forward 5′‐tttactgaggaatggacagta‐3′, reverse 5′‐ggccgttttggatacagcctt‐3′), 402 bp (probe 2; forward 5′‐gagaataggtagctatccatg‐3′,reverse 5′‐cagtgctccatcaggcatcaag‐3′), and 422 bp (probe 3; forward 5′‐gaagatagtgcaggttgctat‐3′, reverse 5′‐aacttcttactgtggttggtc‐3′) in size, from the SOX6 gene (fig 3). Annotated genes in the breakpoint regions of chromosome 9 and 11 were taken from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics Server (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/) as of August 2005.

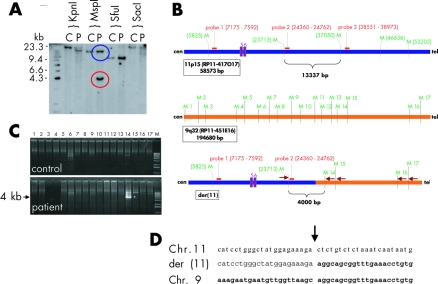

Figure 3 Breakpoint cloning. (A) Southern blot analysis of DNA from the patient and a control digested with the indicated restriction enzymes. The blot was hybridised with probe 2, indicated in B (red box). In the MspI digests, the expected fragment (blue circle) was present in both patient and control DNA, whereas the rearranged fragment (red circle) was present only in DNA from the patient. (B) Overview of the MspI restriction sites (M) and probes used for Southern blot analysis (red boxes). Top, chromosome region 11p15 as deduced from the genomic sequence of clone RP11‐417O17; middle, chromosome region 9q32 as deduced from genomic sequence of clone RP11‐451E16; and bottom, the putative situation on derivative chromosome 11. The sizes of the depicted regions are indicated on the left side. Arrows indicate PCR primers used for amplification of the junction fragment. In addition, the normal and aberrant MspI fragments that hybridised with probe 2 on the Southern blot are shown. Exons 5 and 6 of the SOX6 gene are indicated as purple boxes. (C) PCR with a forward primer from chromosome 11 (bold purple arrow in B) and primers flanking the 17 MspI sites on chromosome 9 as reverse primers (lanes 1–17). PCRs were carried out using patient and control DNAs (M is a 1 kb Plus DNA ladder size marker; Invitrogen). The amplified junction fragment of 4 kb is indicated (*). (D) Chromosome 11, der(11) and chromosome 9 sequences at the der(11) breakpoint in the patient. Chromosome 9 derived sequences are shown in bold.

RESULTS

Cytogenetic and fluorescence in situ hybridisation studies

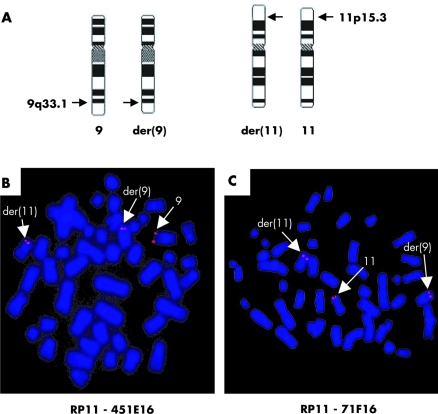

Analysis of the G‐banded metaphase chromosomes of the patient revealed an apparently balanced translocation involving the long arm of chromosome 9 and the short arm of chromosome 11: 46,XY,t(9;11)(q33.1;p15.3) (fig 2A). The karyotypes of the parents were normal. Whole chromosome painting confirmed this result and showed that there was no microscopically visible exchange with other chromosome material (data not shown).

Figure 2 FISH mapping of translocation breakpoints. (A) Ideograms of chromosomes 9, 11, and their derivatives der(9) and der(11) in patient PM. (B) FISH analysis of the patient's chromosomes with the breakpoint spanning clone RP11‐451E16, which yields signals on the normal chromosome 9 and the derivative chromosomes 9 and 11, while clone RP11‐71F16 (C) hybridised to normal chromosome 11 and the derivative chromosomes 9 and 11.

Breakpoint mapping using FISH

The breakpoints were mapped by FISH with a set of BAC and PAC clones covering the chromosomal subregions. In the patient BAC clone RP11‐451E16 from chromosome 9q33.1 and BAC clones RP11‐71F16 and RP11‐417O17 from chromosome 11p15.2 showed split signals and therefore span the breakpoints (fig 2B,C and data not shown).

To refine the breakpoints further we performed Southern blot analysis of DNA from the patient and a control. Hybridisation with probe 2 from BAC clone RP11‐417O17 revealed a 4.3 kb MspI fragment not present in control DNA (fig 3A). This enabled us to locate the breakpoint on chromosome 11. To clone the junction fragment we performed PCR reactions with a combination of a common forward primer located immediately 5′ to probe 2 and 17 different reverse primers (M1–M17), flanking every putative MspI site in the sequence of the chromosome 9 BAC clone RP11‐451E16 on the 3′ side (fig 3B). The combination with primer M14 generated a PCR product of 4 kb only in the patient's DNA and not in DNA from the control. Cloning and subsequent sequencing of this junction fragment revealed the exact position of the breakpoint on derivative chromosome 11 (fig 3C,D). Amplification and sequencing of the junction fragment from the derivative chromosome 9 revealed an identical breakpoint (data not shown). The breakpoint regions do not contain any repeat structure or the presence of repetitive sequence elements, which would explain the recombination event.

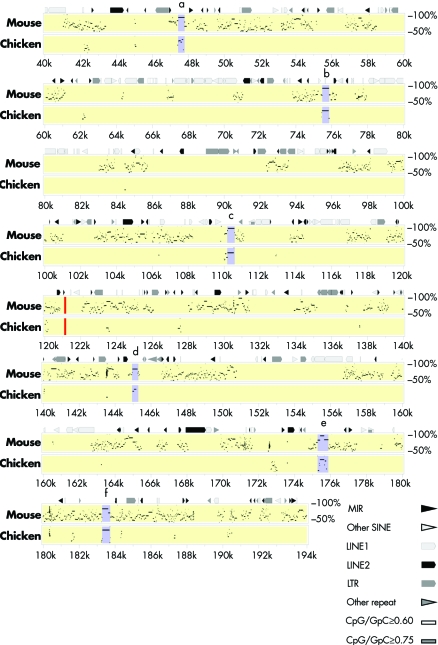

Molecular structure of the breakpoint regions

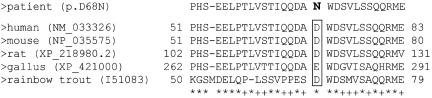

On chromosome 11, the breakpoint is located between exons 6 and 7 of the SOX6 gene. Thus, the translocation disrupts SOX6, leaving the 201 kb 5′ part of the gene intact. Exons 2–6 encode 259 of the 808 amino acids in SOX6, including the leucine zipper and most of the Q‐box at the N‐terminal region. On chromosome 9, the breakpoint falls into an intergenic region of approximately 1 Mb without any annotated, verified gene. Interestingly, the region has a large number of short sequences of 300–600 bp in length, which are highly conserved in evolution (up to 90%) down to chicken (fig 5). Reverse transcription PCR experiments with RNA from different murine tissues, including complete mouse embryos at stages E15.5, E17.5, and E18.5, and skulls from (P0) newborn mice, did not reveal that any of these elements is transcribed (results not shown). Therefore, the sequences most probably represent CNGs. As SOX6 has a major role in cartilage development and has been suggested as a factor in mesenchymal differentiation, SOX6 represents a candidate gene for craniosynostosis. We therefore screened the DNA from 104 patients with different craniosynostoses of sagittal and/or coronal sutures, in whom changes of the most common mutation hot spots in the FGFR1, ‐2, and ‐3 genes were excluded, for mutations in SOX6 by amplification of exons 2–16 (including the complete coding region) and subsequent sequence analysis of the PCR products. In addition to several known polymorphisms, we identified a heterozygous missense mutation at position 263 in the SOX6 cDNA (NM_033326) (c.263G→A) in a 7 year old boy with complex craniosynostosis involving the coronal and sagittal sutures. The mutation resulted in an amino acid exchange from aspartate to asparagine (p.D68N). The mutation affected a highly conserved amino acid in the N‐terminal half of SOX6 (fig 4). The mutation was absent in 200 chromosomes from healthy individuals and 206 chromosomes from patients with various forms of craniosynostosis. Nevertheless, we also detected the mutation in a heterozygous state in the DNA from the patient's apparently healthy mother. She was not available for further clinical examination, but denied any signs of craniosynostosis in her childhood.

Figure 5 Percentage identity plot comparing human with mouse and chicken sequences in a 200 kb interval around the breakpoint region. The breakpoint is indicated by a red bar. Part of the human sequence (NT_008470) was compared with the available orthologous genomic sequences from mouse (NT_039260) and chicken (Contig93 (53‐202)) using PipMaker. Regions (a–f) with a high degree of sequence conservation are indicated by purple bars. The putative CNGs have a length of 300–600 bp and a sequence identity to mouse and chicken of: (A) 89.8%/62.9%, (B) 87.8%/76%, (C) 92%/74.2, (D) 79.5/54.3%, (E) 88%/70.9%, and (F)85.5%/84.4%.

Figure 4 Multiple alignment of amino acid sequences from the N‐terminal portion of SOX6 protein of different species. The accession numbers (in brackets) and the amino acid positions are indicated. The sequence XP_421000 from chicken represents a hypothetical protein,+ is less than mean value plus 2SD, * is more than mean value plus 2SD.

Discussion

Characterisation of breakpoints in patients with apparently balanced chromosome rearrangements has proven a valuable tool in the identification of disease genes.6,7 However, analysis is not always straight forward for two reasons.

Firstly, the association of craniosynostosis and balanced chromosomal translocation in a single patient could be a random coincidence. Interestingly, some years ago Turleau et al8 described a patient with a de novo interstitial deletion of chromosome 9q32‐q34, who showed a very similar craniofacial phenotype to our patient, with brachycephaly, a flat midface, a high forehead, downslanting palpebral fissures, and low set ears. The deletion most probably included the breakpoint region identified in our patient and supports the involvement of chromosome region 9q33.1 in craniosynostosis.

Secondly, position effects may occur and influence expression of genes in a distance from the breakpoint.9,10 Thus, a thorough evaluation of the breakpoint regions and the affected genes is necessary. In the present study we analysed the breakpoints in a male patient with an apparently balanced de novo chromosome translocation t(9;11)(q33.1;p15.3) and a complex craniofacial dysostosis, including craniosynostosis and distinct facial features. The translocation disrupts a region on chromosome 9 containing non‐transcribed patches of high evolutionary sequence conservation and the SOX6 gene on chromosome 11.

The breakpoint on chromosome 9 is located in a region without any annotated genes, but has a large number of short sequences of 300–600 bp highly conserved in evolution (fig 5). Despite several attempts we were not able to amplify these sequences from total RNA of different human and murine tissues (data not shown), indicating that these sequences most probably represent CNGs.11 Several of these CNGs have been identified in the human genome in past years and some have been implicated with a gene regulatory function.11 Recently, it has been demonstrated that translocations may cause disease by disrupting or separating this type of regulatory regions. Examples are the HOXD complex and RIEG/PITX2, TWIST, and SOX9 genes, in which breakpoints affecting regulatory regions up to 900 kb upstream or downstream of the transcription unit downregulate gene expression (reviewed by Dermitzakis et al11, Kleinjan et al12, Velagaleti et al13) Thus, in the present case we have to take into account that the phenotype may be caused by the disruption of sequences present in the breakpoint region of chromosome 9, which may influence the activity of flanking genes in cis. The region is flanked by the genes TLR4 (∼0.7 Mb proximal to the breakpoint) and DBCCR1 (∼0.8 Mb distal to the breakpoint). While DBCCR1 is ubiquitously expressed and encodes a protein generally involved in cell death and tumour development, TLR4 is an interesting candidate gene, as it was recently shown that regulation of osteoclastogenesis by lipopolysaccharide is mediated via its interaction with TLR4 on both osteoclast and osteoblast lineage cells.14,15 Johnson et al16 demonstrated that TLR4 mutant mice consequently develop bones with higher mineral content.

The translocation on chromosome 11 disrupts the SOX6 gene. SOX6 is a member of the SOX gene family, encoding proteins of the HMG box superfamily of DNA binding proteins, which are involved in diverse developmental processes. It has been demonstrated that SOX6, together with SOX5 (LSOX5) and SOX9, plays a critical role in chondrogenesis17,18,19,20 (reviewed by Lefebvre21). In addition, SOX9 and LSOX5 were recently shown to be involved in neural crest development,22,23 suggesting a similar function for SOX6. The flat bones of the vertebrate skull vault develop from the cranial neural crest cells and paraxial mesoderm by intramembranous (and not endochondral ossification). Changes in suture formation may thus be explained not by an effect on chondrogenesis but rather on neural crest development, migration, or differentiation. Nevertheless, Sox5−/−;Sox6−/− double null mouse embryos show severe generalised chondrodysplasia whilst the intramembranous ossification seems to be unaffected.18 Consequently, no changes of the neurocranium were reported, which argues against a loss of function effect in the present case. In contrast, in our patient, the translocation may have led to a shortened mRNA and a stable, truncated SOX6 protein. Interestingly, the translocation left exons 1–6 intact, which encode the N‐terminal part of SOX6, including almost the complete domain important for dimerisation with other factors, possibly LSOX5 (reviewed by Lefebvre21). Thus, a dominant negative effect of a truncated protein via competitive binding is a possible scenario and could explain a mild phenotype, completely different to the knockout mice. Unfortunately, SOX6 is not expressed in lymphoblastoid cell lines, and, as tissue samples from the patient were not available, it could not be tested whether such a truncated product is present. Screening of the SOX6 gene in 104 patients with various forms of craniosynostosis revealed a missense mutation in a single patient with an apparently isolated complex craniosynostosis involving the coronal and sagittal sutures. Interestingly, an evolutionarily conserved aspartate residue at position 68 was changed to asparagine as a result of the mutation. The affected amino acid is located in the N‐terminal part of SOX6 and has so far not been assigned to any functional domain. As the mutation was also found in the patient's apparently non‐affected mother, it remains debatable whether the mutation represents a rare polymorphism or is associated with a craniosynostosis form with reduced penetrance.

In a third scenario, regulatory regions from chromosome 9 translocated to the vicinity of the SOX6 gene might affect the expression of adjacent genes in chromosome region 11p15. Several additional candidate genes come into play when considering an interval of ∼1 Mb. The most intriguing is CALCA for which a regulatory role in bone formation and prevention of bone resorption in hyercalcaemic states has been assigned.24,25,26

In summary, the present case is one of the very rare reports of a de novo balanced translocation found in a patient with syndromic craniosynostosis of unknown aetiology. The finding adds novel candidate genes to the list of factors underlying or at least influencing the development of craniosynostosis. Further analysis of the putative regulatory region, the possible function of SOX6, TLR4, and CALCA in cranial suture biology, and mutation screening for this panel of candidate genes in additional patients will clarify if they play a role in craniosynostosis and in suture biology in general.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the family for their willingness to be involved in this study. We wish to thank Mrs B Schroeder, Mrs. C Menzel, and Mrs S Richter for skilful technical assistance. The balanced chromosomal translocation was detected by routine cytogenetic analysis on G‐banded metaphases in the laboratory of Dr Pruggmayer, Peine, Germany. Expertise in 3D cranial CT imaging was provided by the Department of Neuroradiology, University of Hamburg; Germany. The work was supported by a grant from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) to A Winterpacht, and by the National Genome Research Network (project no. 01GR0105).

Abbreviations

CNG - conserved non‐genic sequence

FISH - fluorescence in situ hybridisation

OFC - occipitofrontal circumference

Footnotes

Competing interests: there are no competing interests

References

- 1.Cohen M M.Epidemiology of craniosynostosis. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc, 2000

- 2.Muenke M, Wilkie A.Craniosynostosis syndromes. vol 4: New York, McGraw‐Hill Companies, Inc. 2001

- 3.Nah H. Suture biology: Lessons from molecular genetics of craniosynostosis syndromes. Clin Orthod Res 2000337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirth J, Nothwang H G, van der Maarel S, Menzel C, Borck G, Lopez‐Pajares I, Brondum‐Nielsen K, Tommerup N, Bugge M, Ropers H H, Haaf T. Systematic characterisation of disease associated balanced chromosome rearrangements by FISH: cytogenetically and genetically anchored YACs identify microdeletions and candidate regions for mental retardation genes. J Med Genet 199936271–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wuchner C, Hilbert K, Zabel B, Winterpacht A. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene (FGFR3): genomic sequence and primer set information for gene analysis. Hum Genet 1997100215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vortkamp A, Gessler M, Grzeschik K H. GLI3 zinc‐finger gene interrupted by translocations in Greig syndrome families. Nature 1991352539–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tao J, Van Esch H, Hagedorn‐Greiwe M, Hoffmann K, Moser B, Raynaud M, Sperner J, Fryns J P, Schwinger E, Gecz J, Ropers H H, Kalscheuer V M. Mutations in the X‐linked cyclin‐dependent kinase‐like 5 (CDKL5/STK9) gene are associated with severe neurodevelopmental retardation. Am J Hum Genet 2004751149–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turleau C, de Grouchy J, Chabrolle J P. [Intercalary deletions of 9q]. Ann Genet 197821234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lettice L A, Horikoshi T, Heaney S J, van Baren M J, van der Linde H C, Breedveld G J, Joosse M, Akarsu N, Oostra B A, Endo N, Shibata M, Suzuki M, Takahashi E, Shinka T, Nakahori Y, Ayusawa D, Nakabayashi K, Scherer S W, Heutink P, Hill R E, Noji S. Disruption of a long‐range cis‐acting regulator for Shh causes preaxial polydactyly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000997548–7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dlugaszewska B, Silahtaroglu A, Menzel C, Kubart S, Cohen M, Mundlos S, Tumer Z, Kjaer K, Friedrich U, Ropers H H, Tommerup N, Neitzel H, Kalscheuer V M. Breakpoints around the HOXD cluster result in various limb malformations. J Med Genet . 2006;43111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dermitzakis E T, Reymond A, Antonarakis S E. Conserved non‐genic sequences—an unexpected feature of mammalian genomes. Nat Rev Genet 20056151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinjan D A, van Heyningen V. Long‐range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am J Hum Genet 2005768–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velagaleti G V, Bien‐Willner G A, Northup J K, Lockhart L H, Hawkins J C, Jalal S M, Withers M, Lupski J R, Stankiewicz P. Position effects due to chromosome breakpoints that map ∼900 kb upstream and ∼1.3 Mb downstream of SOX9 in two patients with campomelic dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet 200576652–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kikuchi T, Matsuguchi T, Tsuboi N, Mitani A, Tanaka S, Matsuoka M, Yamamoto G, Hishikawa T, Noguchi T, Yoshikai Y. Gene expression of osteoclast differentiation factor is induced by lipopolysaccharide in mouse osteoblasts via Toll‐like receptors. J Immunol 20011663574–3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh K, Udagawa N, Kobayashi K, Suda K, Li X, Takami M, Okahashi N, Nishihara T, Takahashi N. Lipopolysaccharide promotes the survival of osteoclasts via Toll‐like receptor 4, but cytokine production of osteoclasts in response to lipopolysaccharide is different from that of macrophages. J Immunol 20031703688–3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson G B, Riggs B L, Platt J L. A genetic basis for the “Adonis” phenotype of low adiposity and strong bones. FASEB J 2004181282–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefebvre V, Li P, de Crombrugghe B. A new long form of Sox5 (L‐Sox5), Sox6 and Sox9 are coexpressed in chondrogenesis and cooperatively activate the type II collagen gene. EMBO J 1998175718–5733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smits P, Li P, Mandel J, Zhang Z, Deng J M, Behringer R R, de Crombrugghe B, Lefebvre V. The transcription factors L‐Sox5 and Sox6 are essential for cartilage formation. Dev Cell 20011277–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akiyama H, Chaboissier M C, Martin J F, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev 2002162813–2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikeda T, Kamekura S, Mabuchi A, Kou I, Seki S, Takato T, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H, Ikegawa S, Chung U I. The combination of SOX5, SOX6, and SOX9 (the SOX trio) provides signals sufficient for induction of permanent cartilage. Arthritis Rheum 2004503561–3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefebvre V. Toward understanding the functions of the two highly related Sox5 and Sox6 genes. J Bone Miner Metab 200220121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung M, Briscoe J. Neural crest development is regulated by the transcription factor Sox9. Development 20031305681–5693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez‐Alcala S, Nieto M A, Barbas J A. LSox5 regulates RhoB expression in the neural tube and promotes generation of the neural crest. Development 20041314455–4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballica R, Valentijn K, Khachatryan A, Guerder S, Kapadia S, Gundberg C, Gilligan J, Flavell R A, Vignery A. Targeted expression of calcitonin gene related peptide to osteoblasts increases bone density in mice. J Bone Miner Res 1999141067–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schinke T, Liese S, Priemel M, Haberland M, Schilling A F, Catala‐Lehnen P, Blicharski D, Rueger J M, Gagel R F, Emeson R B, Amling M. Increased bone mass is an unexpected phenotype associated with deletion of the calcitonin gene. J Clin Invest 20021101849–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schinke T, Liese S, Priemel M, Haberland M, Schilling A F, Catala‐Lehnen P, Blicharski D, Rueger J M, Gagel R F, Emeson R B, Amling M. Decreased bone formation and osteopenia in mice lacking alpha‐calcitonin gene‐related peptide. J Bone Miner Res 2004192049–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]