Abstract

Cocaine use is a significant problem in the US and it is well established that cocaine binds to the dopamine transporter (DAT) in the brain. This study was designed to determine if the DAT levels measured by 99mTc TRODAT SPECT brain scans are altered in cocaine dependent subjects and to explore clinical correlates of such alterations. SPECT brain scans were acquired on 21 cocaine dependent subjects and 21 healthy matched controls. There were significantly higher DAT levels in cocaine dependent subjects compared to controls for the anterior putamen (p = 0.003; Cohen’s d effect size = 0.98), posterior putamen (p < 0.001; effect size = 1.32), and caudate (p = 0.003; effect size = 0.97). DAT levels in these regions were 10%, 17%, and 8% higher in the cocaine dependent subjects compared to controls. DAT levels were unrelated to craving, severity of cocaine use, or duration of cocaine use, but DAT levels in the caudate and anterior putamen were significantly (p < 0.05) negatively correlated with days since last use of cocaine.

Keywords: Dopamine transporter, Cocaine dependence, SPECT

I. Introduction

Cocaine binds to the dopamine transporter (DAT) in the brain (Ritz et al., 1987), thereby blocking uptake resulting in increases in synaptic dopamine in the striatum and the nucleus accumbens (Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988; Egilmez et al., 1995). The magnitude of the blockage of the DAT in humans correlates with the degree of self-reported “high” from cocaine (Volkow et al., 1997). Aspects of the mechanism of cocaine binding to the dopamine transporter has been studied at the cellular level (Chen and Reith, 2000). Studies have revealed that cocaine induces increases in the plasma membrane DAT immunoreactivity (Little et al., 2002) and results in the movement of DAT to the cell surface (Daws et al., 2002).

In vitro autoradiographic studies of cocaine binding in brain sections from nonhuman primates have found the highest density of binding sites for cocaine in the basal ganglia, the brain region with the highest density of dopamine terminals (Madras and Kaufman, 1994). In humans, autoradiographic studies of post mortem striatal specimens from cocaine users have revealed significant increases in DAT binding sites (Little et al., 1993), and specific increases in the density of high affinity sites on the DAT (Staley et al., 1994), compared with control subjects. Additionally, in nonhuman primates, exposure to cocaine over an 18 month period, compared to animals not exposed to cocaine, has been found to lead to a higher density of DAT binding sites, specifically in the ventral striatum where the shell of the nucleus accumbens is found (Letchworth et al., 2001). Though most studies support the claim that cocaine use causes an increase in DAT levels, there are some investigations yielding different findings in animals including lower uptake in the nucleus accumbens, or no changes in the striatum, when measured 24 hours after the last of 3 daily administrations of cocaine in rats (Izenwasser and Cox, 1990). Similarly, normal levels of DAT have been reported in the autopsied brains of chronic cocaine users (Wilson et al., 1996). It has been speculated that differences across studies in brain regions examined, time elapsed since last cocaine use, and type of radioligand used for quantifying DAT may explain the inconsistency of the findings (Volkow et al., 1996).

The long term behavioral effects of cocaine may be related to alterations in dopamine transmission that follow from DAT blockade. As a consequence of high levels of synaptic dopamine, chronic cocaine use is associated with reduction in availability of dopamine D2 receptors that persists 3-4 months after detoxification (Volkow et al., 1993). Imaging studies have documented higher DAT levels for recently (about 4 days) abstinent cocaine-using subjects compared to control (Malison et al., 1998; Jacobsen et al., 2000). No studies, however, have examined DAT levels as a function of clinical characteristics of cocaine use among active cocaine dependent subjects. Based on primate data on duration and dosage of cocaine exposure in relation to DAT (Letchworth et al., 2001), it would be expected that duration of cocaine use and severity of cocaine usage (amount of use in past month) might be associated with higher DAT levels. Because withdrawal symptoms appear related to a depletion in dopamine (Dackis and Gold, 1985), abstinence would be expected to be associated with a recovery of DAT levels, although the time period for recovery to relatively normal levels is uncertain. Craving is another clinical characteristic of sustained cocaine use that might be associated with alterations in DAT. Studies have found that increased mu-opioid receptor binding, another neurotransmitter system that affects dopamine systems in the brain, is positively corrected with craving (Zubieta et al., 1996; Gorelick et al., 2005).

In this study, 99mTc TRODAT-1 was used to image DAT levels using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in 21 cocaine dependent patients who were recently abstaining and 21 healthy controls. The following hypotheses were tested: (a) There is significantly greater 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake for cocaine patients compared to controls, and (b) The pattern of 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake will co-vary with clinical characteristics of cocaine use: negatively for time since last use, positively for amount of cocaine being used, positively for duration of cocaine addiction, and positively for craving.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Cocaine dependent subjects were currently seeking outpatient counseling for their cocaine use. The control sample contained 21 age-matched healthy volunteers. All healthy volunteers included in the study had no significant medical, neurological or psychiatric diseases. All subjects gave written informed consent and all procedures for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board and Radiation Safety Committee of the University of Pennsylvania and by the Food and Drug Administration.

2.2. Clinical assessments

For the treatment-seeking subjects, a DSM-IV diagnosis of cocaine dependence was made by a trained doctoral level psychologist using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al., 1994). Cocaine dependent subjects were excluded if they met diagnostic criteria for current opioid dependence, dementia, other irreversible organic brain syndrome, or if there was evidence of current psychotic symptoms or a medical illness that can create marked change in mental state. Clinical characteristics of cocaine use were also measured at this initial assessment. Craving was assessed with a three-item Cocaine Craving Scale (Weiss et al., 1997; Weiss et al., 2003). The three questions on the Cocaine Craving Scale were “please rate how strong your desire was to use cocaine during the last 24 hours,” “please imagine yourself in the environment in which you previously used drugs and/or alcohol...if you were in this environment today, what is the likelihood that you would use cocaine?” and “please rate how strong your urges are for cocaine when something in the environment reminds you of it.” Response options ranged from 0 for “no desire/likelihood of use” to 9 for “strong desire/likelihood of use.” The composite score was a sum of these three items, ranging from 0 to 27. Severity of cocaine use was measured using an item from the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992) administered by trained interviewers. The item asked about the number of days of cocaine use during the past month. Duration of cocaine use (in years) was obtained by self-report as part of a cocaine history form. An observed urine sample was also obtained at this assessment visit. An on-site analysis system was used to screen the urines for illicit opioids, benzyolecognine (a cocaine metabolite), amphetamines, methamphetamines, and benzodiazepines.

2.3. Imaging

After completing diagnostic and other assessments for the treatment program, cocaine dependent patients were scheduled to receive the SPECT scan, which was generally completed within two weeks of the diagnostic visit but before treatment began. When patients arrived for the SPECT scan, they were asked to report the day of their last use. Patients were excluded from the study if they reported use of cocaine within the past 24 hours.

At the start of the scan, individuals were placed at rest on the imaging table in the supine position. An intravenous catheter was placed in an antecubital vein and capped with a well containing normal saline. Subjects were then injected with 740 MBq (20 mCi) of 99mTc TRODAT-1. Vital signs and EKGs were recorded before and after the injection.

Patients were scanned 3-4 hours following the administration of 99mTc TRODAT-1. All images were acquired on a triple headed gamma camera equipped with fan beam collimators (Picker Prism 3000XP, Cleveland, OH). The camera resolution is 6.7 mm with a spatial resolution for reconstructed SPECT scans of 8-10 mm. The acquisition parameters included a continuous mode with 40 projection angles over a 120° arc to obtain data in a 128 × 128 matrix with a pixel width of 2.11 mm and a slice thickness of 3.56 mm.

All images were processed and reconstructed using the same procedure. Transverse reconstruction backprojection was applied to the raw data. A Butterworth, low pass filter was then applied with an order of 4 and a cutoff of 0.351 cm-1. Photon attenuation correction was performed using Chang’s first order correction method using an attenuation coefficient of 0.11 cm-1 (Chang, 1978).

The frames that were acquired from 3-4 hours after the injection of 99mTc TRODAT-1 were summed and imported into an image analysis package called PETVIEW. Image analysis was performed blinded to the clinical diagnosis of each patient. A standardized template containing six regions of interest (ROIs) was transposed manually onto subregions of the right and left basal ganglia (caudate, anterior putamen and posterior putamen). The regions were different shapes to accommodate the different structures (some more round and some more oblong) and ranged from 7-14 pixels (corresponding to an area of 3-62 mm2). This standardized template had been validated in previous studies (Amsterdam and Newberg, 2007; Newberg et al., 2007; Swanson et al., 2005). Basal ganglia ROIs were placed on 3 consecutive slices so that the ROIs were within each structure both on each slice and across the slices (i.e. in the x,y, and z dimensions). In this manner, they represent a “punch biopsy” of each of the structures. In addition, beginning 5 slices above the basal ganglia, an elliptical ROI was placed on two consecutive slices of the supratentorial uptake representing non-specific binding.

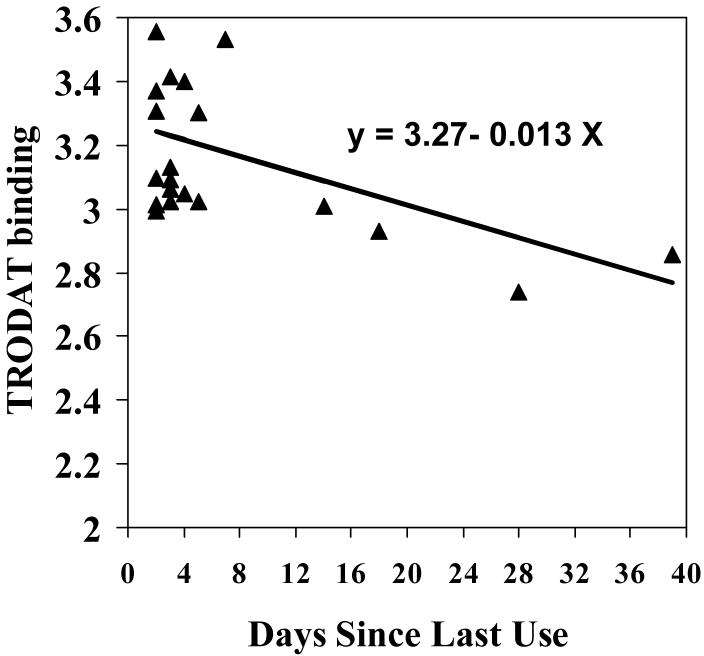

An example scan of a cocaine dependent subject showing the placement of the basal ganglia ROIs is given in Figure 1. Distribution volume ratios were calculated for these ROIs based upon a reference region consisting of the supratentorial structures above the basal ganglia and the following equation: (ROI-Reference Region)/Reference Region. Right and left values for each area were averaged to yield final scores for the caudate, anterior putamen, and posterior putamen.

Figure 1.

TRODAT SPECT scan of a cocaine subject showing placement of the regions of interest over the caudate, anterior and posterior putamen. The ROIs are smaller than the actual structures so they represent a “punch biopsy” of dopamine transporter binding.

Full kinetic modeling of the uptake of 99mTc TRODAT-1 in the striatum of cocaine dependent subjects has not been performed. However, the above ratio method using a reference region has been employed in other studies using 99mTc TRODAT-1 and was expected to be adequate for the following reasons. The peak uptake of 99mTc TRODAT-1 is typically in the range of 30-40 minutes (Kushner et al., 1999). Moreover, studies of 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake in both baboons (Acton et al,. 1999) and humans (Acton et al., 2000) have examined the relationship between data from the reference region (ratio) method employed here and full kinetic analysis based on rapid arterial blood sampling (using non linear regression analysis and graphical analysis measures of distribution volume ratios). In the range of 3-4 hours post-injection, the correlations between data from the simpler reference region method and data from full kinetic analysis were above 0.80 in humans; at 4-5 hours post-injection, these correlations were above 0.90 (Acton et al., 2000). The timing of the scans in our study was typically between 3 and 4.5 hours post-injection, substantially beyond the expected point of peak uptake in non-cocaine users. In addition, in the Acton et al. (2000) study, there was a nonsignificant relationship between peak equilibrium time and higher values of distribution volume ratios, suggesting that longer time to peak uptake was not strongly affected by DAT levels.

3. Results

For the cocaine dependent patients, 1 identified himself as White, 18 as African American, and 2 as Other (Table 1). Seventy-six percent (n=16) of the sample were men. The average age of patients was 42.8 (SD = 6.2) years. More than half (12 patients; 57%) were employed and 16 patients (76%) lived alone. Most (67%) used crack cocaine, and the average days of use in the month prior to treatment was 12.1 days. At the time of the scans, patients had last used cocaine on average 7.5 days (SD = 9.7; range = 2 to 39) previously. No discrepancies were found between the urine screen for cocaine obtained at the intake assessment and the self-report of days since last use obtained at the SPECT scan visit (i.e., for all patients who reported last use at a time point earlier than the urine screen, the urine result was negative for cocaine). Most (90.5%) of the cocaine dependent patients smoked cigarettes. While alcohol was not the primary drug of abuse, the average number of days in the past 30 drinking alcohol was 7.4. No use of heroin or methamphetamines in the past 30 days was reported.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cocaine dependent and control subjects

| Characteristic | Cocaine Dependent Subjects (N=21) | Control Subjects (N=21) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 42.8 (6.2) | 40.3 (7.0) |

| Sex, n (%) male | 16 (76.2) | 14 (66.7) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 1 (4.8) | 11 (52.4) |

| African-American | 18 (85.7) | 8 (38.1) |

| Hispanic | 2 (9.5) | 0 |

| Native American/Alaskan | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Smoke cigarettes, n (%) | 19 (90.5) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Days used alcohol (past 30), Mean (SD) | 7.4 (7.3) | NA |

| Days used cocaine (past 30), Mean (SD) | 12.1 (7.5) | 0 |

| Days since last use of cocaine, Mean (SD) | 7.5 (9.7) | 0 |

| Years of cocaine use, Mean (SD) | 11.7 (5.6) | 0 |

| Days used other psychotropic drug use in past 30 days, Mean (SD) | ||

| Heroin | 0 | 0 |

| Methamphetamine | 0 | 0 |

| Marijuana | 1.7 (3.0) | 0 |

NA = not assessed.

The control sample was also mostly male (14/21; 67%), with 8 patients identifying themselves as African American, 11 as White, and 2 Other (Table 1). The average age of the control sample was 40.3 (SD = 7.0) years. None of the subjects in the control sample had used illicit drugs during the past month. A minority (9.5%) were smokers; none were abusing alcohol, although the numbers of days of alcohol use in the past 30 was not assessed.

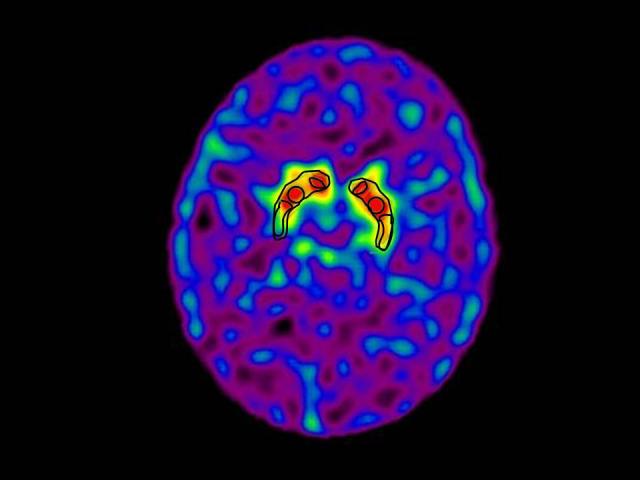

Multivariate analysis of variance testing for between-group (control vs. cocaine dependent patients) mean differences across all three regions (anterior putamen, posterior putamen, caudate) revealed that 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake in cocaine dependent subjects was higher than controls (F=6.14, DF = 3, 38, p=0.0016). Univariate t-tests were significant for between group differences for the anterior putamen (t =3.18; DF = 40; p = 0.003), posterior putamen (t = 4.27; DF = 40; p < 0.001), and caudate (t = 3.14; DF = 40; p = 0.003). Effect sizes were large for these between group differences (Table 2). DAT levels were 10%, 17%, and 8% higher in the cocaine dependent subjects compared to controls for the anterior putamen, posterior putamen, and caudate, respectively. Examples of scans for a cocaine dependent subject and a control subject are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Mean DAT binding scores for cocaine dependent subjects and normal controls

| DAT binding: brain region | Cocaine dependent subjects N=21 | Normal controls N=21 | Effect Size |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Cohen’s d | P- value | |

| Caudate | 3.17 (0.25) | 2.94 (0.23) | 0.97 | 0.003 |

| Anterior putamen | 2.95 (0.28) | 2.68 (0.26) | 0.98 | 0.003 |

| Posterior putamen | 2.50 (0.28) | 2.14 (0.25) | 1.32 | < 0.001 |

Figure 2.

TRODAT SPECT scan of a control subject (A) and a cocaine subject (B) showing increased TRODAT binding in the anterior putamen of the cocaine subject (arrow).

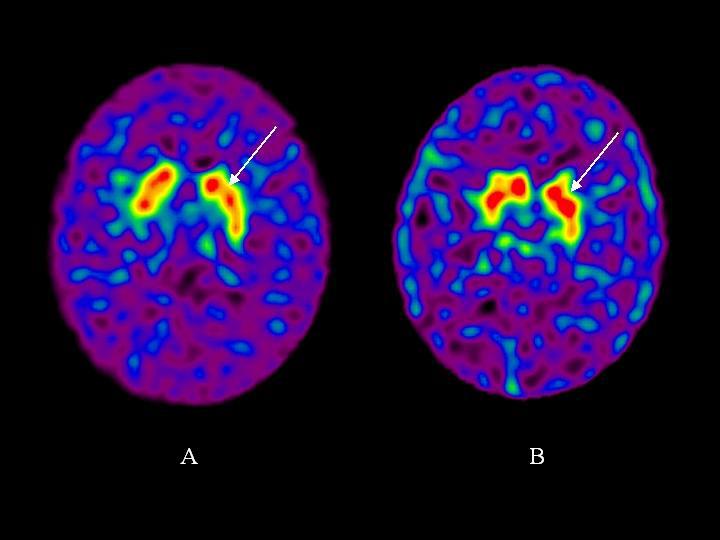

Pearson correlation between 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake and clinical characteristics of cocaine use revealed a significant relation between days since last use and 99mTc TRODAT-1 update in the caudate and anterior putamen (Table 3). No significant relationships were observed between 99mTc TRODAT-1 update and duration of cocaine usage, amount of cocaine use, or craving. Using a regression equation predicting 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake in the caudate from days since last use, it was estimated that DAT levels would return to normal levels (mean of control sample) by 25.4 days (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Pearson Correlations between DAT binding scores and clinical characteristics of cocaine use within cocaine dependent subjects (N=21)

| DAT binding: brain region | Days since last use | Number of days of cocaine use in previous 30 days | Duration of cocaine use (years) | Craving |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caudate | -0.50 * | -0.07 | 0.04 | -0.27 |

| Anterior putamen | -0.53 * | -0.21 | 0.19 | -0.004 |

| Posterior putamen | -0.39 | 0.03 | -0.15 | 0.07 |

P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of days since last use of cocaine in relation to TRODAT binding levels in the caudate.

4. Discussion

The results support the first hypothesis, that there are group differences in 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake and hence DAT levels between cocaine patients and controls. All three specific subregions of the basal ganglia (anterior putamen, posterior putamen, caudate) were significantly different in cocaine patients compared to controls, although the effects were strongest for the putamen regions.

It is possible that confounds between the cocaine dependent and control samples may explain the between-group differences in DAT levels. For example, the groups differed in rates of smoking. Smoking, however, has been associated with decreased DAT levels (Krause et al., 2002; Newberg et al., 2007), and thus this factor would have hindered between-group differences given the higher percentage of smokers among the cocaine dependent patients relative to the controls. The groups also likely differed on alcohol use, although the exact amount of alcohol use in the control sample was not assessed (but there were no alcohol abusers). Animal and human studies of DAT in relationship to alcohol have yielded mixed results (Carroll et al., 2006; Ho et al., 2001; Tupala et al., 2001, Budygin et al., 2001), thus it is not clear how alcohol use may have affected the results. Other unmeasured confounds, such as past psychiatric disorders, may also be relevant to the findings.

These findings are generally consistent with previous animal studies which have evaluated changes in the DAT related to cocaine administration and withdrawal. One study showed that rats receiving cocaine for three days showed an increase in the DAT half life which lasted approximately 7 days (Kimmel et al., 2001). A review of a number of other animal studies supports the notion that in the short term withdrawal period from cocaine, there may be an increase of DAT levels in the striatum which may return to normal or even decrease over time (Kuhar and Pilotte, 1996; Sharpe et al., 1991).

The current 99mTc TRODAT-1 findings are also consistent with several human studies that have evaluated the DAT in cocaine patients. Studies of post-mortem brains demonstrated an overall increase of DAT in the striatum of cocaine abusers compared to controls (Little et al., 1999; Mash et al., 2002; Staley et al., 1994). Malison et al (1998) used 123I beta-CIT SPECT and found that striatal dopamine transporters were significantly increased (approximately 20%) in acutely abstinent cocaine-abusing subjects (96 hours or less). Another study using 123I beta-CIT SPECT also showed approximately a 14% increase in DAT availability in acutely abstinent (3.7 days on average) cocaine subjects compared to controls (Jacobsen et al., 2000). However, these studies did not observe subjects who were abstinent over a longer period of time as evaluated in the present study.

The results from the present study also showed that 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake was negatively correlated with the duration of time since last use of cocaine. Thus, as cocaine subjects remain abstinent, it appears that DAT levels approach the levels in the control sample after approximately 25 days. Though it would seem that the normalization of DAT levels may be the result of maintained abstinence, it may also be worthwhile to consider the possibility that the pre-existing levels of DAT may have an impact on treatment response. Stated more plainly, patients with higher DAT levels may be more likely to relapse or fail treatment than patients with DAT levels that more closely approximate normal to begin with.

The lack of significant correlations of 99mTc TRODAT-1 uptake with severity of cocaine use and craving is notable in the context of other studies reporting correlations of both severity of cocaine use and craving variables with mu-opioid receptor binding (Zubieta et al., 1996; Gorelick et al., 2005). Thus, while DAT levels may be an important aspect of the dopamine system, the role of mu-opioid receptors in regulating dopaminergic neurons may be more relevant to severity of use, which in turn affects the subjective experience of craving.

These findings may have important implications for understanding the physiological actions of cocaine, the addictive component of cocaine use, and also the potential of future therapeutic interventions. The higher levels of DAT and inverse correlation with time since last use might be tested against withdrawal symptoms and the potential for long term recovery. However, this was a preliminary study and therefore this correlation is in need of replication.

A limitation of this study is the sample size. Future studies will need larger numbers of subjects, and more specifically a greater number people who managed to accumulate 10 or more days of abstinence from cocaine. Another limitation in the current study is that information about duration of cocaine use and last day of cocaine use was acquired through self-report. To further assess the relationship between the reduction of DAT levels and cocaine abstinence, future studies should consider obtaining objective measures of drug use/abstinence (e.g., urine samples) on the day of imaging procedures. A further limitation of the current study is that no kinetic modeling data based on repeated blood samples over time exists to document the time to peak uptake of 99mTc TRODAT-1 in cocaine users. It is possible that because of higher levels of DAT, the time to peak uptake in cocaine users is longer than in non-cocaine using controls, although it is highly unlikely that it would extend to beyond the 3-4 hour period when the scan was performed. Moreover, if it did, the scan would have occurred before peak uptake, thereby producing lower values and decreasing the size of the effect when comparing cocaine users to controls. A final limitation is that coregistered MRI scans were not performed to help guide regions of interest. Such coregistration should be conducted in future studies to confirm the specificity of the findings in this preliminary study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acton PD, Kushner SA, Kung MP, Mozley PD, Plössl K, Kung HF. Simplified reference region model for the kinetic analysis of [99mTc]TRODAT-1 binding to dopamine transporters in nonhuman primates using single-photon emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:518–526. doi: 10.1007/s002590050420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acton PD, Meyer PT, Mozley PD, Plössl K, Kung HF. Simplified quantification of dopamine transporters in humans using [99mTc]TRODAT-1 and single photon emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:1714–1718. doi: 10.1007/s002590000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam JD, Newberg AB. A preliminary study of dopamine transporter binding in bipolar and unipolar depressed patients and healthy controls. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;55:167–170. doi: 10.1159/000106476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budygin EA, Phillips PE, Wightman RM, Jones SR. Terminal effects of ethanol on dopamine dynamics in rat nucleus accumbens: an in vitro voltammetric study. Synapse. 2001;42:77–79. doi: 10.1002/syn.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll MR, Rodd ZA, Murphy JM, Simon JR. Chronic ethanol consumption increases dopamine uptake in the nucleus accumbens of high alcohol drinking rats. Alcohol. 2006;40:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LT. A method for attenuation correction in radionuclide computed tomography. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1978;25:638–643. [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Reith ME. Structure and function of the dopamine transporter. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;405:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Gold MS. New concepts in cocaine addiction: the dopamine depletion hypothesis. Neurosci Biobeh Rev. 1985;9:469–477. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(85)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daws LC, Callaghan PD, Moron JA, Kahlig KM, Shippenberg TS, Javitch JA, Galli A. Cocaine increases dopamine uptake and cell surface expression of dopamine transporters. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2002;290:1545–1550. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egilmez Y, Jung ME, Lane JD, Emmett-Oglesby MW. Dopamine release during cocaine self-administration in rats: effect of SCH23390. Brain Res. 1995;701:142–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00987-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams BW. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders--Patient Edition. American Psychiatric Press; Washington D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick DA, Kim YK, Bencherif B, Boyd SJ, Nelson R, Copersino M, Endres CJ, Dannals RF, Frost JJ. Imaging brain mu-opioid receptors in abstinent cocaine users: time course and relation to cocaine craving. Bio Psychiatry. 2005;57:1573–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho M, Segre M. Individual and combined effects of ethanol and cocaine on the human dopamine transporter in neuronal cell lines. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;299:229–233. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izenwasser S, Cox BM. Daily cocaine treatment produces a persistent reduction in [3H]dopamine uptake in vitro in rate nucleus accumbens but not in striatum. Brain Res. 1990;531:338–341. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90797-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Staley JK, Malison RT, Zoghbi SS, Seibyl JP, Kosten TR, Innis RB. Elevated central serotonin transporter binding availability in acutely abstinent cocaine-dependent patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1134–1140. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel HL, Carroll FI, Kuhar MJ. RTI-76, an irreversible inhibitor of dopamine transporter binding, increases locomotor activity in the rat at high doses. Brain Res. 2001;897:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause KH, Dresel SH, Krause J, Kung HF, Tatsch K, Ackenheil M. Stimulant-like action of nicotine on striatal dopamine transporter in the brain of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:111–113. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702002821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhar MJ, Pilotte NS. Neurochemical changes in cocaine withdrawal. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:260–264. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SA, McElgin WT, Kung MP, Mozley PD, Plossl K, Meegalla SK, Mu M, Dresel S, Vessotskie JM, Lexow N, Kung HF. Kinetic modeling of [99mTc]TRODAT-1: a dopamine transporter imaging agent. J Nuclear Med. 1999;40:150–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letchworth SR, Nader MA, Smith HR, Friedman DP, Porrino LJ. Progression of changes in dopamine transporter binding site density as a result of cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2799–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02799.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KY, Elmer LW, Zhong H, Zhang L. Cocaine induction of dopamine transporter trafficking to the plasma membrane. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:436–445. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.2.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KY, Kirkman JA, Carroll FI, Clark TC, Duncan GE. Cocaine use increases [3H]WIN 35428 binding sites in human striatum. Brain Res. 1993;628:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90932-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KY, Zhang L, Desmond T, Frey KA, Dalack GW, Cassin BJ. Striatal dopaminergic abnormalities in human cocaine users. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:238–245. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madras BK, Kaufman MJ. Cocaine accumulates in dopamine-rich regions of primate brain after i.v. administration: comparison with mazindol distribution. Synapse. 1994;18:261–275. doi: 10.1002/syn.890180311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash DC, Pablo J, Ouyang Q, Hearn WL, Izenwasser S. Dopamine transport function is elevated in cocaine users. J Neurochem. 2002;81:292–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malison RT, Best SE, van Dyck CH, McCance EF, Wallace EA, Laruelle M, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, Price LH, Kosten TR, Innis RB. Elevated striatal dopamine transporters during acute cocaine abstinence as measured by [123I] beta-CIT SPECT. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:832–834. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberg A, Lerman C, Wintering N, Ploessl K, Mozley PD. Dopamine transporter binding in smokers and nonsmokers. Clin Nucl Med. 2007;32:452–455. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000262980.98342.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe LG, Pilotte NS, Mitchell WM, De Souza EB. Withdrawal of repeated cocaine decreases autoradiographic [3H]mazindol-labelling of dopamine transporter in rat nucleus accumbens. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;203:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90804-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley JK, Hearn WL, Ruttenber AJ, Wetli CV, Mash DC. High affinity cocaine recognition sites on the dopamine transporter are elevated in fatal cocaine overdose victims. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:1678–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson RL, Newberg AB, Acton PD, Siderowf A, Wintering N, Alavi A, Mozley PD, Plossl K, Udeshi M, Hurtig H. Differences in [99mTc]TRODAT-1 SPECT binding to dopamine transporters in patients with multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:302–307. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1667-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupala E, Kuikka JT, Hall H, Bergstrom K, Sarkioja T, Rasanen P, Mantere T, Hiltunen J, Vepsalainen J, Tiihonen J. Measurement of the striatal dopamine transporter density and heterogeneity in type 1 alcoholics using human whole hemisphere autoradiography. Neuroimage. 2001;14:87–94. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Hitzemann R, Logan J, Schlyer DJ, Dewey SL, Wolf AP. Decreased dopamine D2 receptor availability is associated with reduced frontal metabolism in cocaine abusers. Synapse. 1993;14:169–177. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin RW, Fowler JS, Abumrad NN, Vitkun S, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Pappas N, Hitzemann R, Shea CE. Relationship between subjective effects of cocaine and dopamine transporter occupancy. Nature. 1997;386:827–830. doi: 10.1038/386827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Gatley SJ, MacGregor RR, Wolf AP. Cocaine uptake is decreased in the brain of detoxified cocaine abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00073-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Hufford C, Muenz LR, Najavits LM, Jansson SB, Kogan J, Thompson HJ. Early prediction of initiation of abstinence from cocaine: use of a craving questionnaire. Am J Addict. 1997;6:224–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Mazurick C, Berkman B, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, Barber JP, Blaine J, Salloum I, Moras K. The relationship between cocaine craving, psychosocial treatment, and subsequent cocaine use. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1320–1325. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Levey AI, Bergeron C, Kalasinsky K, Ang L, Peretti F, Adams VI, Smialek J, Anderson WR, Shannak K, Deck J, Niznik HB, Kish SJ. Striatal dopamine, dopamine transporter, and vesicular monoamine transporter in chronic cocaine users. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:428–439. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Gorelick DA, Stauffer R, Ravert HT, Dannals RF, Frost JJ. Increased mu opioid receptor binding detected by PET in cocaine-dependent men is associated with cocaine craving. Nat Med. 1996;2:1225–1229. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]