Abstract

To date, there has been a lack of evidence-based guidance on the frequency of visual field examinations required to identify clinically meaningful rates of change in glaucoma. The objective of this perspective is to provide practical recommendations for this purpose. The primary emphasis is on the period of time and number of examinations required to measure various rates of change in mean deviation (MD) with adequate statistical power. Empirical data were used to obtain variability estimates of MD while statistical modelling techniques derived the required time periods to detect change with various degrees of visual field variability. We provide the frequency of examinations per year required to detect different amounts of change in 2, 3 and 5 years. For instance, three examinations per year are required to identify an overall change in MD of 4 dB over 2 years in a patient with average visual field variability. Recommendations on other issues such as examination type, strategy and quality are also made.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

Assessment of visual field damage is the major index of the functional impact of glaucoma with direct relevance to quality of life measures.1–6 Visual field change was used as a primary endpoint for progression in the recent glaucoma trials,7–12 and its measurement is the cornerstone of glaucoma management influencing therapeutic decisions.

The objective of this perspective is to provide practical recommendations for measuring clinically relevant rates of glaucomatous visual field progression to help identify patients at risk for visual impairment. They focus on the frequency of examinations required for detecting various amounts and rates of visual field change.

STATEMENT OF NEED

In routine clinical glaucoma practice, the frequency of visual field examinations varies significantly13 and usually falls substantially below recommendations for maintaining minimum practice standards.14 An unacceptable number of glaucoma patients become visually impaired or even blind while under care.15–21 Several factors including over-reliance on intraocular pressure (IOP) to measure treatment adequacy could contribute to this finding. Having sufficient visual field data and analysis methods may help the ophthalmologist deliver more targeted care resulting in better functional outcomes.

There are three main barriers to performing sufficiently frequent visual field examinations.

Data volume and analysis

Standard automated perimetry (SAP) generates large volumes of data, which may be time-consuming and difficult to interpret without statistical software. There are no generally recommended methods for usage of the analyses and translating them to clinical practice.

Resource allocation

Financial resources allocated to perimetry are often inadequate and vary across jurisdictions. The need for more frequent and regular visual field examinations has been poorly emphasised, perhaps because of the lack of a strong evidence-based rationale to monitor disease progression.

Definition of progression

While criteria for progression have been clearly defined in clinical trials, the identical criteria may not be applicable to clinical practice. The lack of a definition of clinically significant progression and how to use it practically may be a disincentive to performing frequent examinations. In turn, clinical decisions could be made with inadequate information, or serious progression could be missed because of an insufficient number of examinations.

METHOD TO MEASURE VISUAL FIELD PROGRESSION

Standard automated perimetry (SAP) should be used

Knowledge on visual field progression in glaucoma has come almost exclusively from SAP. Recent clinical trials in glaucoma have used only SAP as a primary functional endpoint, and clinical benefit from their findings is easiest if SAP is used.

What to measure

There are several approaches to analysing visual field progression, including event (comparison of a follow-up examination to a baseline) and trend (regression analyses to measure rates of change) based methods, each with a myriad of variations. Analyses can be subdivided into individual points, visual field sectors, or the whole field. For the purpose of simplicity and universality, it is recommended that rates of change are measured in units of mean deviation or mean defect (MD), the average pointwise difference between a given test result and the normal age matched reference value.

Newer forms of testing should not be performed at the expense of SAP

It is recognised that patients can only perform a limited number of tests during clinic visits, and the number of patient visits is limited by physician patient loads, reimbursement and other resource considerations. While tests such as short-wavelength automated perimetry (SWAP) and frequency-doubling technology (FDT or Matrix) perimetry can provide additional or confirmatory evidence, they remain in the clinical research domain. In routine clinical practice, they should not be conducted at the expense of SAP examinations. Similarly, new imaging techniques of the optic disc and retinal nerve fibre (RNFL) are widely used in some clinical practices and provide complementary information. However, they cannot substitute perimetry as a surrogate measure of visual field change.

NUMBER AND FREQUENCY OF VISUAL FIELD EXAMINATIONS

Visual field examinations should be conducted in all glaucoma patients and suspects. The appropriate frequency and intervals set out below are determined by the rate of change to be detected and measurement variability. These recommendations specify the minimum requirements. There are many circumstances when the frequency of examinations should be increased because of a higher perceived risk of functional loss—for example, suspicion of optic disc change, inadequate IOP control, advanced field damage, pseudoexfoliation, increased age and morbidity in the fellow eye.

It is important to obtain sufficient number of reliable examinations in the early follow-up to establish a good baseline and rule out rapid progression. Clinicians should take advantage of the more frequent appointments in the first year and, if possible, perform a visual field examination at each visit.

Rates of MD change in most glaucoma patients vary from 0 to −2.5 dB/year, depending on the severity of disease, treatment and population samples.22–25 They are pragmatic estimates of visual disability patients can suffer at given rates of progression and baseline damage. For example, a patient with early loss (MD = −4 dB) and a rapid rate of progression (−2 dB/year) can be expected to have total visual disability (−30 dB) in 13 years. In a patient with moderate loss (−12 dB), that rate of change will have the same outcome in 9 years, while slower progression (−0.2 dB/year) is unlikely to lead to blindness in that patient’s lifetime.

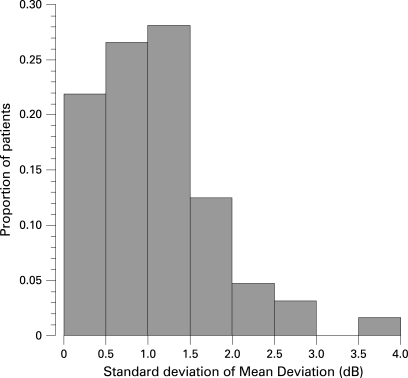

The ability (statistical power) to detect a given rate of visual field change expressed in MD/year will depend on the variability of MD over time, the number of examinations and the amount of change we wish to detect. Using the distribution of standard deviations (SD) of MD from glaucoma patients in a longitudinal study26 (fig 1), low, moderate and high variability are defined as an SD of 0.5, 1 and 2 dB, respectively.

Figure 1. Distribution of intra-individual standard deviation (SD) of MD values in patients followed for up to 12 years.

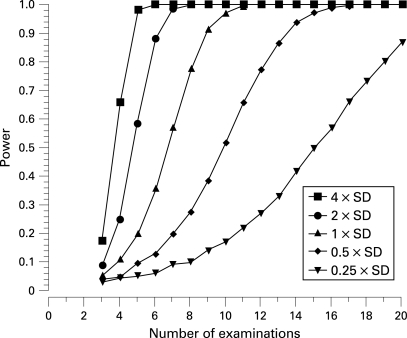

The statistical power to detect various rates of MD change (expressed as a multiple of the SD) for given numbers of examinations is shown in fig 2. Detecting a very rapid rate (four times the SD of MD variability) of change with 80% power requires between four and five examinations. In other words, such a magnitude of change will be detected four times out of five with between four and five examinations. On the other hand detecting a small rate of change (1/4 of the SD of MD variability) requires 19 examinations for the same power.

Figure 2. Statistical power to detect a significant rate of change of MD expressed as a function of variability (SD of the MD values) and number of examinations.

In practical terms, these data can be expressed as the time period required to detect MD deterioration of −0.5 dB/year, −1.0 dB/year and −2.0 dB/year with 80% power (table 1) with one, two and three examinations per year. These data clearly show that detecting rates of visual field change with certainty generally requires many visual fields; however, larger rates of change require fewer examinations. In a patient with rapid progression (−2 dB/year) and low variability, the time required to detect change with 80% power is 5 years if examinations are performed once a year, 2.5 years with two examinations per year and as little as 1.7 years if examinations are performed three times per year. In a more typical scenario with moderate field progression (−0.5 dB/year) and moderate variability, the respective times to detection are 13, 6.5 and 4.3 years for one, two and three examinations per year.

Table 1. Time period (years) required to detect various rates of MD change with 80% power in visual fields with low, moderate and high degrees of variability with one (a), two (b) and three (c) examination per year.

| (a) 1 examination/year Progression rate (dB/year) | Variability | ||

| Low | Moderate | High | |

| −0.25 | 13 | 19 | 30 |

| −0.5 | 9 | 13 | 19 |

| −1.0 | 6 | 9 | 13 |

| −2.0 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

| (b) 2 examinations/year Progression rate (dB/year) | Variability | ||

| Low | Moderate | High | |

| −0.25 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 15 |

| −0.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 8.5 |

| −1.0 | 3 | 4.5 | 6.5 |

| −2.0 | 2.5 | 3 | 4.5 |

| (c) 3 examinations/year Progression rate (dB/year) | Variability | ||

| Low | Moderate | High | |

| −0.25 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 10 |

| −0.5 | 3 | 4.3 | 6.3 |

| −1.0 | 2 | 3 | 4.3 |

| −2.0 | 1.7 | 2 | 3 |

OTHER REQUIREMENTS FOR MEASURING VISUAL FIELD PROGRESSION

Examination quality

Examination quality is important. Automatic trust in the reliability indices produced by the software should be avoided. Besides false-positive rates, other indices (fixation losses and specifically false negative rates) may not accurately reflect examination quality. Consideration should be given to other indicators of examination quality, such as the perimetrist’s notes (if available), patient attention, artefacts such as lens rim defects, poor centration, incorrect refractive correction, etc, before including or discarding examinations to evaluate progression. High-quality visual field examinations often depend on perimetrists being well informed, trained and motivated. Learning effects can sometimes be difficult to account for, as they can be negligible, or persist over several examinations. Generally speaking, unless there are obvious explanations, significant improvements in the initial period of follow-up can be attributed to learning.

Examination strategy

Visual field change should only be determined with examination strategies that estimate thresholds, such as Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm (SITA) and full threshold bracketing strategies. The same strategy (eg, always SITA Standard) and test pattern (eg, always 30–2 or always 24–2, and not a mixture of, for example, 30–2 and 10–2) is always much better for determining visual field change.

Progression software

Visual field examinations generate a considerable amount of data. Software programs that perform objective and automated analyses are available and should be used.27–30 All reliable examinations should be used in the analyses to measure progression accurately. Decision-making based on examination of grey-scale plots should be avoided.

CONCEPTS THAT ERRONEOUSLY HINDER THE USE OF SAP TO MEASURE PROGRESSION

While stressing the importance of measuring visual field progression, the evidence supporting some commonly held views should be re-examined.

Is SAP sensitive enough?

It is often quoted that up to 50% of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are lost before onset of visual field damage.31 More recent studies with SAP reported lesser degrees of RGC loss.32 33 Many methodological issues regarding scaling of visual field measurements34 and localised losses of RGCs (which make up a smaller proportion of overall RGC loss but are more readily detectable by SAP32) make SAP measurements relevant. The sensitivity of imaging devices to identify early glaucomatous visual field loss at a specificity of 90–95% is around 70%.35–37 The ability of clinicians to identify structural glaucomatous damage is similar to that of the imaging devices.38 39 This means that automated or clinical evaluation of structural damage fails to identify around 30% of eyes with established early visual field loss.

Is detection of early visual field loss important?

Visual field loss is strongly associated with quality-of-life measures.1–6 Recent evidence shows that motor vehicle accidents are significantly related to the level of SAP loss,40–42 in spite of patients being well within the legal visual requirements to hold a driving licence and having only early field damage in the worse eye.40

Are visual field examinations difficult to perform reliably?

It is often thought that visual field examinations are difficult to perform. This attitude can potentially transfer to ophthalmology trainees, staff and patients. Inappropriate or inaccurate instructions to patients can lead to anxiety and unreliable results. For example, perimetrists and patients should be made aware that during a typical examination, around 50% of the stimuli are not expected to be seen. Appropriate and standardised patient instructions produce reliable and usable results in the vast majority of patients.43 44

Can visual fields be performed with cataract and macular degeneration?

Cataract and macular degeneration are often co-morbidities of glaucoma. The effect of mild to moderate cataract on the visual field can be small or even negligible,45 46 though more advanced cataract can have a larger impact.47 48 While cataract can confound the glaucomatous visual field, software to largely remove its influence is available.27 49 Macular degeneration will, to a certain extent, change the appearance of central glaucomatous visual field defects and their progression. Central visual fields should always be corroborated with fundus examination. Tools to aid patient fixation in automated perimetry are available and should be used.

Can small amounts of visual field progression be detected?

The amount of visual field change that can be detected depends on the variability and number of available examinations, as described above. Both theoretical and empirical evidence indicates that small amounts of clinically significant change can be detected with an adequate number of examinations and sufficient follow-up time.50 51

Are other perimetric techniques more sensitive than SAP?

Recent evidence supporting the notion that perimetric techniques such as SWAP and FDT perimetry are clearly more sensitive at detecting field progression is weak.52 53 While there is active research in this area, it is recommended that for routine practice, other perimetric techniques should be considered adjunct and not be performed at the expense of SAP.

Are structural tests more sensitive markers of the disease?

Recent research shows weak concordance between visual field and structural measures of progression.26 54 In routine practice, given a certain number of tests, it is more effective to perform the same test more frequently than a variety different tests less frequently. Evidence supporting earlier detection of progression with optic disc and RNFL measurements is difficult to obtain.26 Examination of the optic disc and RNFL is of unquestionable importance providing additional and complementary information about disease progression. However, if resources are limited, modern structural tests should not be substituted for SAP examinations if the frequency of the latter falls below recommended levels.

Are measurements of structure more reliable because they are objective?

Because obtaining optic disc or RNFL images does not require a subjective response from the patient, they may be erroneously considered “real” and without measurement error. However, these measurements can vary because of many patient- and instrument-related factors. Furthermore, the frequency of imaging required to identify progression is comparable with that for visual fields.55 56 Similar to analyses of visual fields, variability can confound the interpretation of change.57 58

RECOMMENDATIONS

On the basis of the discussion above, we make the following recommendations.

Perform sufficient examinations to detect change

The progression status of the patient is unknown unless there is enough information. Table 2(a) shows the rate of MD change corresponding to total change in MD over 2, 3 and 5 years in visual fields with moderate variability. The frequency of examinations per year required to detect the corresponding amounts of MD change is shown in table 2(b).

Table 2. Rates of visual field change corresponding to total change in mean deviation (MD) over 2, 3 and 5 years (a) and the number of visual fields per year required to detect the corresponding change with 80% power (b).

| (a) Total MD change (dB) | Progression rate (dB/year) | ||

| 2 years | 3 years | 5 years | |

| −1.0 | −0.5 | −0.3 | −0.2 |

| −2.0 | −1.0 | −0.7 | −0.4 |

| −4.0 | −2.0 | −1.3 | −0.8 |

| (b) Total MD change (dB) | Annual examinations | ||

| 2 years | 3 years | 5 years | |

| −1.0 | 7 | 6 | 4 |

| −2.0 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| −4.0 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

Six visual field examinations should be performed in the first 2 years

This rules out the presence of rapid progression (−2 dB/year or worse) and establishes a good set of baseline data.

Measure the rate of visual field progression

Estimating the rate of progression is invaluable for guiding therapeutic decisions and estimating the likelihood of visual impairment during the patient’s lifetime. In most cases, establishing visual field progression requires several years.

Use the same threshold test

Any analysis of progression can only be performed if the same threshold algorithm and test pattern is used.

Pay attention to examination quality

Examinations of poor quality will likely lead to an erroneous assessment of progression. There should not be automatic reliance on the reliability indices. Unless there are other reasons (such as obvious learning effects, high false-positive errors, rim artefacts) examinations should not be removed from the analyses.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Detection of visual field progression requires understanding of variability, the magnitude of change that is considered clinically significant and the number of visual fields required to detect this change with adequate statistical power. In addition to rates of change, other approaches such as event-based analyses are also available and useful in certain clinical situations. Clinical decisions on patient management require more than a formulaic approach based on visual field progression because risk factors such as baseline damage, age, and IOP may have different relative weights in driving these decisions. For this reason, these recommendations are not a protocol, but a practical guide and template for the examination frequency to detect different rates and/or magnitudes of change, as well as other considerations for the appropriate use of perimetry for detecting glaucomatous progression.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr P Artes for discussion on the power calculations.

Footnotes

Funding: Supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Allergan, Inc and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-11357).

Competing interests: BCC is or has been a consultant for Allergan, Mimetogen, Pfizer and QLT, and has received research support from Alcon, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Heidelberg Engineering, Pfizer and Welch Allyn. DFGH is or has been a consultant for Allergan, Carl Zeiss Meditec and Pfizer, and has received research support from Allergan, Carl Zeiss Meditech, Heidelberg Engineering, Optovue, Pfizer, Reichert and Santen. FJG has been reimbursed by Alcon, Allergan, Carl Zeiss Meditec and Pfizer for attending conferences and running educational programmes. BB is a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditec and received travel support from Allergan and research funding from Carl Zeiss Meditec. ACV has been a consultant, received honoraria or teaching funding from Alcon, Allergan, Merck Sharpe Dohme and Pfizer, and is a developer of PROGRESSOR, a commercially available software package for visual field analysis. AH is or has been a consultant for Alcon Allergan, Carl Zeiss Meditec and Pfizer, and has received research support from Alcon, Allergan, Carl Zeiss Meditec and Santen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gutierrez P, Wilson MR, Johnson C, et al. Influence of glaucomatous visual field loss on health-related quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:777–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parrish RK, 2nd, Gedde SJ, Scott IU, et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:1447–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherwood MB, Garcia-Siekavizza A, Meltzer MI, et al. Glaucoma’s impact on quality of life and its relation to clinical indicators. A pilot study. Ophthalmology 1998;105:561–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jampel HD, Friedman DS, Quigley H, et al. Correlation of the binocular visual field with patient assessment of vision. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002;43:1059–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson P, Aspinall P, Papasouliotis O, et al. Quality of life in glaucoma and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma 2003;12:139–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman LG, Komaroff E, Heijl A, et al. Treatment and vision-related quality of life in the early manifest glaucoma trial. Ophthalmology 2005;112:1505–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS) 1. Study design and methods and baseline characteristics of study patients. Control Clin Trials 1994;15:299–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;126:487–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon MO, Kass MA. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: design and baseline description of the participants. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:573–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, et al. Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial: design and baseline data. Ophthalmology 1999;106:2144–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Canadian Glaucoma Study Group Canadian Glaucoma Study: 1. Study design, baseline characteristics, and preliminary analyses. Can J Ophthalmol 2006;41:566–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musch DC, Lichter PR, Guire KE, et al. The Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study: study design, methods, and baseline characteristics of enrolled patients. Ophthalmology 1999;106:653–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hertzog LH, Albrecht KG, LaBree L, et al. Glaucoma care and conformance with preferred practice patterns. Examination of the private, community-based ophthalmologist. Ophthalmology 1996;103:1009–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman DS, Nordstrom B, Mozaffari E, et al. Glaucoma management among individuals enrolled in a single comprehensive insurance plan. Ophthalmology 2005;112:1500–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon YH, Kim CS, Zimmerman MB, et al. Rate of visual field loss and long-term visual outcome in primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eid TM, Spaeth GL, Bitterman A, et al. Rate and amount of visual loss in 102 patients with open-angle glaucoma followed up for at least 15 years. Ophthalmology 2003;110:900–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zahari M, Mukesh BN, Rait JL, et al. Progression of visual field loss in open angle glaucoma in the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 2006;34:20–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattenhauer MG, Johnson DH, Ing HH, et al. The probability of blindness from open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1998;105:2099–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver JE, Hattenhauer MG, Herman D, et al. Blindness and glaucoma: a comparison of patients progressing to blindness from glaucoma with patients maintaining vision. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133:764–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen PP. Blindness in patients with treated open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2003;110:726–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forsman E, Kivela T, Vesti E. Lifetime visual disability in open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. J Glaucoma 2007;16:313–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson DR, Drance SM, Schulzer M. Natural history of normal-tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2001;108:247–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artes PH, Nicolela MT, LeBlanc RP, et al. Visual field progression in glaucoma: total versus pattern deviation analyses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:4600–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SD, Katz J, Quigley HA. Analysis of progressive change in automated visual fields in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:1419–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shigeeda T, Tomidokoro A, Araie M, et al. Long-term follow-up of visual field progression after trabeculectomy in progressive normal-tension glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2002;109:766–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Artes PH, Chauhan BC. Longitudinal changes in the visual field and optic disc in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 2005;24:333–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bengtsson B, Lindgren A, Heijl A, et al. Perimetric probability maps to separate change caused by glaucoma from that caused by cataract. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1997;75:184–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heijl A, Lindgren G, Lindgren A, et al. Extended empirical statistical package for evaluation of single and multiple fields: Statpac 2. Mills RP, Heijl A, eds. Perimetry update 1990/1. New York: Kugler & Ghedini, 1991:303–15 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viswanathan AC, Fitzke FW, Hitchings RA. Early detection of visual field progression in glaucoma: a comparison of PROGRESSOR and STATPAC 2. Br J Ophthalmol 1997;81:1037–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber J. Atlas der computerperimetrie. Berlin: Springer, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quigley HA, Addicks EM, Green WR. Optic nerve damage in human glaucoma. III. Quantitative correlation of nerve fiber loss and visual field defect in glaucoma, ischemic neuropathy, papilledema, and toxic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1982;100:135–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerrigan-Baumrind LA, Quigley HA, Pease ME, et al. Number of ganglion cells in glaucoma eyes compared with threshold visual field tests in the same persons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000;41:741–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quigley HA, Dunkelberger GR, Green WR. Retinal ganglion cell atrophy correlated with automated perimetry in human eyes with glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1989;107:453–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garway-Heath DF, Caprioli J, Fitzke FW, et al. Scaling the hill of vision: the physiological relationship between light sensitivity and ganglion cell numbers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000;41:1774–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford BA, Artes PH, McCormick TA, et al. Comparison of data analysis tools for detection of glaucoma with the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1145–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, et al. Comparison of the GDx VCC scanning laser polarimeter, HRT II confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope, and stratus OCT optical coherence tomograph for the detection of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:827–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Berry CC, et al. Discriminating between normal and glaucomatous eyes using the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph, GDx Nerve Fiber Analyzer, and Optical Coherence Tomograph. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:985–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wollstein G, Garway-Heath DF, Fontana L, et al. Identifying early glaucomatous changes. Comparison between expert clinical assessment of optic disc photographs and confocal scanning ophthalmoscopy. Ophthalmology 2000;107:2272–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badala F, Nouri-Mahdavi K, Raoof DA, et al. Optic disk and nerve fiber layer imaging to detect glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:724–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haymes SA, Leblanc RP, Nicolela MT, et al. Risk of falls and motor vehicle collisions in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:1149–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGwin G, Jr, Owsley C, Ball K. Identifying crash involvement among older drivers: agreement between self-report and state records. Accident; analysis and prevention 1998;30:781–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szlyk JP, Mahler CL, Seiple W, et al. Driving performance of glaucoma patients correlates with peripheral visual field loss. J Glaucoma 2005;14:145–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Cello KE, et al. Baseline visual field characteristics in the ocular hypertension treatment study. Ophthalmology 2002;109:432–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson CA, Nelson-Quigg JM. A prospective three-year study of response properties of normal subjects and patients during automated perimetry. Ophthalmology 1993;100:269–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart WC, Rogers GM, Crinkley CM, et al. Effect of cataract extraction on automated fields in chronic open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:875–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrillo MM, Artes PH, Nicolela MT, et al. Effect of cataract extraction on the visual fields of patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:929–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith SD, Katz J, Quigley HA. Effect of cataract extraction on the results of automated perimetry in glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:1515–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guthauser U, Flammer J. Quantifying visual field damage caused by cataract. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;106:480–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heijl A, Lindgren G, Olsson J. A package for the statistical analysis of visual fields. Doc Ophthalmol Proc Ser 1987;49:153–68 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, et al. Measuring visual field progression in the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2003;81:286–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vesti E, Johnson CA, Chauhan BC. Comparison of different methods for detecting glaucomatous visual field progression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:3873–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Demirel S, Johnson CA. Incidence and prevalence of short wavelength automated perimetry deficits in ocular hypertensive patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:709–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haymes SA, Hutchison DM, McCormick TA, et al. Glaucomatous visual field progression with frequency-doubling technology and standard automated perimetry in a longitudinal prospective study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:547–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strouthidis NG, Vinciotti V, Tucker AJ, et al. Structure and function in glaucoma: The relationship between a functional visual field map and an anatomic retinal map. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:5356–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owen VM, Strouthidis NG, Garway-Heath DF, et al. Measurement variability in Heidelberg Retina Tomograph imaging of neuroretinal rim area. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:5322–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jampel HD, Vitale S, Ding Y, et al. Test–retest variability in structural and functional parameters of glaucoma damage in the glaucoma imaging longitudinal study. J Glaucoma 2006;15:152–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chauhan BC, LeBlanc RP, McCormick TA, et al. Test–retest variability of topographic measurements with confocal scanning laser tomography in patients with glaucoma and control subjects. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brigatti L, Weitzman M, Caprioli J. Regional test–retest variability of confocal scanning laser tomography. Am J Ophthalmol 1995;120:433–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]