Abstract

Although G protein-coupled MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are expressed in neurons of the mammalian brain including in humans, relatively little is known about the influence of native MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors on neuronal melatonin signaling. Whereas human cerebellar granule cells (CGC) express only MT1 receptors, mouse CGC express both MT1 and MT2. To study the effects of altered neuronal MT1/MT2 receptors, we used CGC cultures prepared from immature cerebella of wild-type mice (MT1/MT2 CGC) and MT1- and MT2-knockout mice (MT2 and MT1 CGC, respectively). Here we report that in MT1/MT2 cultures, physiological (low nanomolar) concentrations of melatonin decrease the activity (phosphorylation) of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) whereas a micromolar concentration was ineffective. Both MT1 and MT2 deficiencies transformed the melatonin inhibition of ERK into melatonin-induced ERK activation. In MT1/MT2 CGC, 1 nM melatonin inhibited serine/threonine kinase Akt, whereas in MT1 and MT2 CGC, this concentration was ineffective. Under these conditions, both MT1 and MT2 deficiencies prevented melatonin from inhibiting forskolin-stimulated cAMP levels and cFos immunoreactivity. We demonstrated that selective removal of native neuronal MT1 and MT2 receptors has profound effect on the intracellular actions of low/physiological concentrations of melatonin. Since the expression of MT1 and MT2 receptors is cell-type-specific and species-dependent, we postulate that the pattern of expression of neuronal melatonin receptor types in different brain areas and cells could determine the capabilities of endogenous melatonin in regulating neuronal functioning.

Keywords: melatonin, cerebellar, MT1, MT2, ERK, Akt

1. Introduction

Since the discovery of the in-vitro (Giusti et al., 1995) and in-vivo (Uz et al., 1996) neuroprotective actions of melatonin, studies have focused on the neuronal effects of supraphysiological, i.e., micromolar, concentrations of this hormone. On the other hand, the endogenous levels of serum and cerebrospinal fluid melatonin are in a low nanomolar range (Rousseau et al., 1999). These levels show dramatic diurnal variability (Pääkkönen et al., 2006). The nanomolar concentrations of melatonin act on the G protein-coupled melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 (formerly known as Mel1a and Mel1b) (Dubocovich et al., 2003; Witt-Enderby et al., 2006). These receptors, which typically are linked to the inhibition of cAMP-mediated signaling, are expressed in various types of mammalian neurons including in the human brain (Brunner et al., 2006; Jimenez-Jorge et al., 2007; Savaskan et al., 2002, 2005; Thomas et al., 2002; Uz et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2006, 2007). The pattern of MT1 and MT2 expression appears to be cell-type specific and species-dependent. For example, whereas mouse cerebellar granule cells (CGC) express both MT1 and MT2 receptors, human CGC express MT1 but not MT2 mRNA (Al-Gholu et al., 1998).

MT1 and MT2 receptors are operative as monomers and homo- and hetero-dimers (Ayoub et al., 2002, 2004). Typically, studies of melatonin-receptor-type-specific effects employ cells transfected with MT1/MT2 receptors (Ayoub et al., 2002, 2004; Chan et al., 2002), and cells that endogenously express only one type of melatonin receptors, e.g., MT1 (Bordt et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2002). Alternatively, selective MT1 and MT2 knockouts have been established in mice and these animals have been used in studies of central nervous system functioning (Larson et al., 2006; Sumaya et al., 2005).

In cells expressing only MT1 receptors, melatonin increases the activity (i.e., phosphorylation) of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK), a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (Bordt et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2002), whereas in cells expressing both MT1 and MT2 receptors, melatonin inhibited ERK phosphorylation (Cui et al., 2008). In these latter conditions, melatonin also inhibited the phosphorylation (i.e., activity) of serine/threonine kinase Akt (also known as protein kinase B) (Cui et al., 2008).

Although experimental models based on transfecting cells that do not express native melatonin receptors with exogenous MT1 and MT2 receptors are useful in characterizing the signaling mediated by these receptors (i.e., by individual receptor types vs. their combinations), the limitations of these constructs include an unnatural cellular environment. For example, data obtained from transfected non-neuronal cells are not directly applicable to neuronal conditions, suggesting the need for prudent use of the heterologous cell transfection technique (Gabellini et al., 1994).

To study the effects of altered MT1/MT2 receptors on neuronal melatonin signaling, we used a model of primary cultures of mouse CGC. These cultures are advantageous because they comprise a uniform population of neurons. In addition, we took advantage of the availability of MT1- and MT2-knockout mice. Hence, in this work, CGC cultures were prepared from the cerebella of wild-type mice (MT1/MT2 CGC) and MT1- and MT2-knockout mice (MT2 and MT1 CGC, respectively). Furthermore, we focused these studies on the effects of the receptor-relevant low nanomolar concentrations of melatonin.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of melatonin on ERK phosphorylation

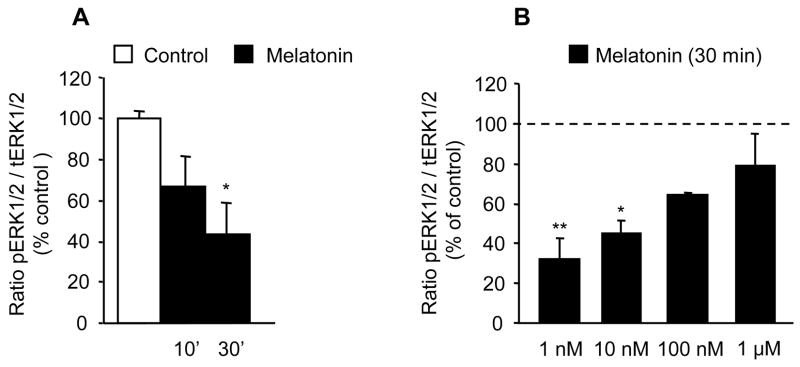

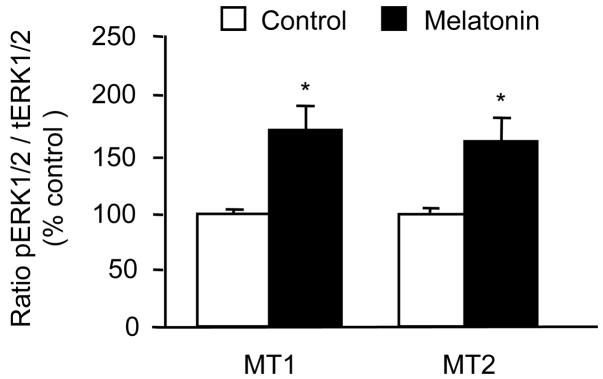

The initial qualitative assay of the effects of 1 nM melatonin on ERK phosphorylation revealed a major difference in the response of CGC with both native melatonin receptors intact (MT1/MT2 CGC) vs. CGC in which only one type of native melatonin receptor remained intact; in MT1/MT2 CGC melatonin decreased ERK phosphorylation whereas in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC, the same treatment increased ERK phosphorylation (data not shown). The quantitative analysis of the action of 1 nM melatonin showed that in MT1/MT2 CGC, the inhibition of ERK was evident at 10 min of treatment and became significant at 30 min (Fig. 1A). Studies of concentration dependency demonstrated that melatonin inhibits ERK in a low nanomolar range, and that this effect is lost with 1 μM melatonin (Fig. 1B). In MT 1 CGC and MT2 CGC, melatonin stimulated ERK instead of inhibiting it. This stimulatory effect of 1 nM melatonin on ERK phosphorylation was statistically significant after 10 min (Fig. 2) (the same effect remained evident at 30 min; data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effects of melatonin on ERK activity, i.e., phosphorylated forms of ERK (pERK1/2) in MT1/MT2 CGC. The signals for phosphorylated proteins were normalized by measuring the immunoreactivity of their respective total ERK in the same blot. Results (mean ± SEM; n = 4–6 different culture preparations) are presented as a percentage of the corresponding vehicle-treated control (open bar). (A) 1 nM melatonin (closed bars) decreases ERK phosphorylation in 10 min, and this becomes significant by 30 min. *p<0.05 vs. the corresponding control; ANOVA followed by the Dunnett’s test. (B) Increasing melatonin concentration up to 1 μM (30 min incubation) failed to activate ERK (presented as a % of the 100% control indicated by a dotted line; * p<0.05; ** p<0.01 compared to control).

Fig. 2.

Effects of 1 nM melatonin on ERK activity, i.e., phosphorylated forms of ERK (pERK1/2) in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC. The signals for phosphorylated proteins were normalized by measuring the immunoreactivity of their respective total ERK in the same blot. Results (mean ± SEM; n = 4–6 different culture preparations) are presented as a percentage of the corresponding vehicle-treated control (open bars). After 10 min incubation, melatonin (closed bars) increased the pERK content in both MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC. *p<0.05 vs. the corresponding control (t-test).

2.2. Effects of melatonin on Akt phosphorylation

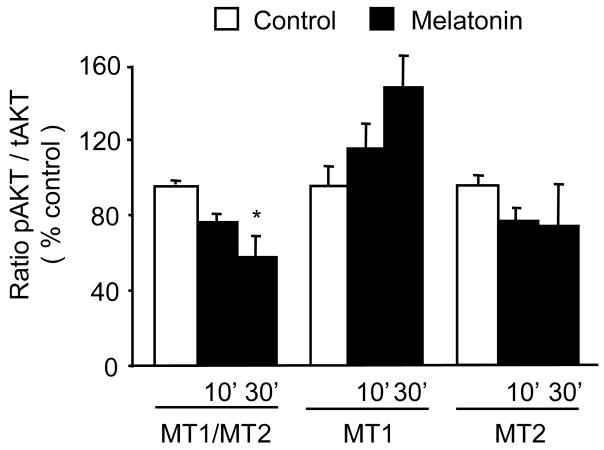

Similar to the inhibition of ERK phosphorylation by nanomolar melatonin in MT1/MT2 CGC, in these cultures melatonin inhibited Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 3). This inhibition was absent in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC. However, in contrast to ERK, under these experimental conditions Akt phosphorylation was not stimulated by melatonin in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC. Thus, the observed trend to Akt stimulation by melatonin in MT1 CGC did not reach statistical significance; F[(2, 6) = 3.069, p = 0.121] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of 1 nM melatonin on Akt activity, i.e., phosphorylated forms of Akt (pAkt) in MT1/MT2, MT1, and MT2 cerebellar granule cells (CGC). Results (mean ± SEM; n=3–4 different culture preparations) are presented as a percentage of the corresponding vehicle-treated control (open bars). Melatonin decreased the pAkt content in MT1/MT2 CGC (*p<0.05 vs. the corresponding control; ANOVA followed by the Dunnett’s test). There were no statistically significant changes in pAkt protein levels after melatonin in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC.

2.3. Effects of melatonin on cAMP levels in forskolin-treated CGC

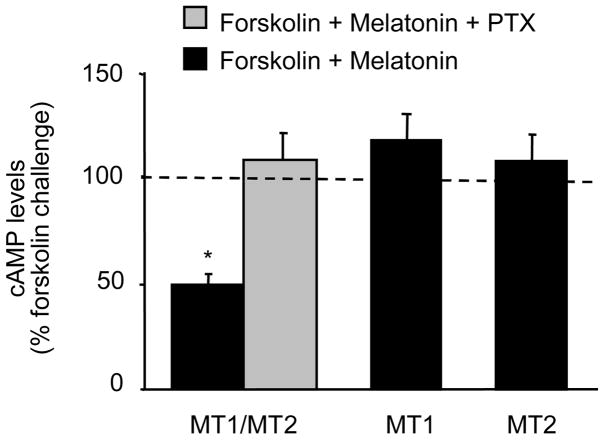

In CGC with intact native MT1/MT2 receptors, 1 nM melatonin decreased forskolin-stimulated cAMP. This effect of melatonin was blocked by PTX, an uncoupler of G proteins from their respective receptors (Fig. 4). Both in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC, melatonin failed to affect cAMP levels of forskolin-treated cultures (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of melatonin on cAMP levels in forskolin-treated CGC. Melatonin (1 nM) was added to the medium 10 min before adding the forskolin (1 μM) and the cotreatment was continued for an additional 10 min. In MT1/MT2 CGC, PTX (0.5μg/ml) was added 16 h prior to the melatonin and forskolin cotreatment. cAMP content was measured with an enzyme immunoassay. In each CGC type (i.e., MT1/MT2, MT1, and MT2), the forskolin-only-treated group was included. The results are presented as a percentage of the corresponding forskolin challenge (i.e., forskolin only, which is taken as 100% and indicated by a doted line) (mean ± SEM; n= 3–4 different culture preparations; *p<0.001 vs. the corresponding forskolin challenge; t-test). Note that melatonin was able to reduce cAMP levels only in MT1/MT2 CGC and that this effect was inhibited by PTX.

2.4. Effects of melatonin on cFos immunoreactivity in forskolin-treated CGC

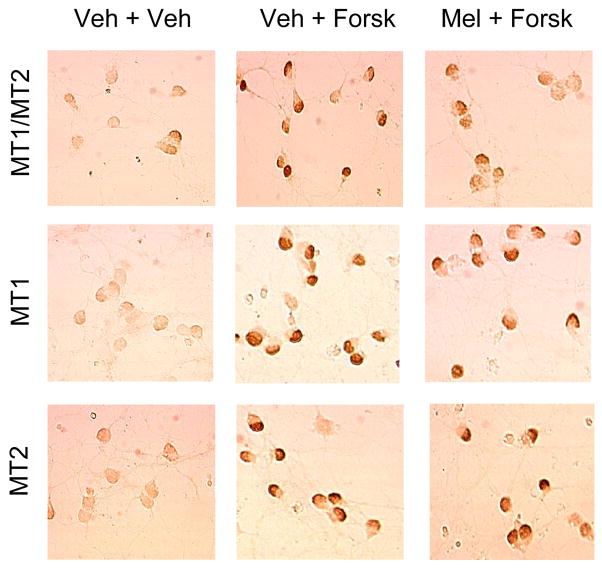

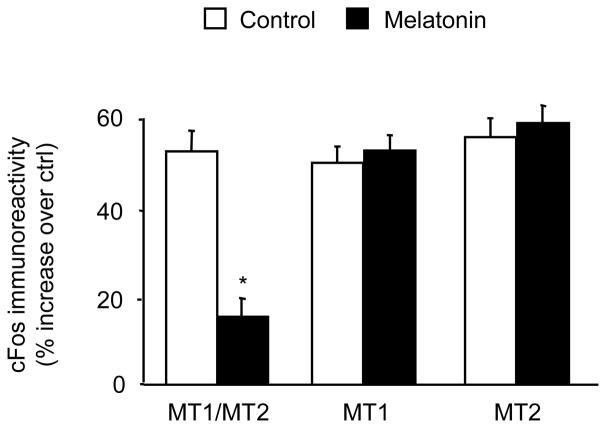

Forskolin treatment increases cFos protein content. In all three types of CGC (MT1/MT2, MT1, and MT2) forskolin increased cFos immunoreactivity. Melatonin (1 nM) reduced this forskolin-stimulated cFos increase in MT1/MT2 CGC but not in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC (examples shown in Fig. 5; quantitative data shown in Fig. 6). Under these experimental conditions, melatonin alone did not significantly alter cFos immunoreactivity (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

An example of the effects of melatonin on forskolin-induced cFos immunoreactivity is shown in the representative images. Forskolin (Forsk, 1 μM) was present for 2 h, and melatonin (Mel, 1 nM) was added 30 min prior to adding the forskolin. Melatonin attenuated forskolin–stimulated cFos immunoreactivity in MT1/MT2 CGC but not in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC.

Fig. 6.

Effects of melatonin on forskolin-induced cFos immunoreactivity: quantitative results. Melatonin (1 nM) attenuated forskolin (1 μM)–stimulated cFos immunoreactivity in MT1/MT2 CGC but not in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC. Forskolin was present in the culture for 2 h, and melatonin was added 30 min prior to the addition of forskolin. Immunoreactivity was measured as the optical density of the cFos-immunopositive cells (see Experimental procedures for details). The results (mean ± SEM; n = 3) are presented as the percentage of increase compared to the control vehicle-treated group (*p<0.001 compared to the corresponding forskolin-only-treated group; nested ANOVA).

3. Discussion

The main finding in this work is that the presence of native MT1/MT2 melatonin receptors in mouse CGC mediates the effects of low nanomolar concentrations of melatonin on intracellular signaling pathways. We found that in MT1/MT2 CGC, melatonin inhibited ERK and Akt kinases. This is similar to the recently reported action of melatonin on ERK and Act in non-neuronal cells that express both MT1 and MT2 receptors (Cui et al., 2008). On the other hand, previous work has shown that in cells which express only MT1 receptors, melatonin stimulates ERK (Bordt et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2002). We found a similar stimulatory effect of melatonin in MT1 CGC. Also in MT2 CGC, melatonin stimulated instead of inhibiting ERK. Previous pharmacological experiments have already suggested that an acute stimulation of MT2 receptors may lead to ERK activation (Radio et al., 2006). Furthermore, the presence of both types of native melatonin receptors appears to be necessary for melatonin-mediated Akt inhibition in mouse CGC.

It has been proposed that cell type characteristics and the expression levels of specific signaling intermediates for individual MAPK pathways may contribute to a differential melatonin-triggered activation of MAPK subtypes (Chan et al., 2002). Our results suggest that in their native environment, e.g., in mouse CGC, melatonin receptors couple to this signaling system when both MT1 and MT2 types are present at the same time and also if each is present alone. However, the functioning of CGC with heterogeneous melatonin receptors appears to differ from functioning of CGC with only one type of these receptors. Since MT1 and MT2 receptors are capable of dimerizing (Ayoub et al., 2002, 2004), it is possible that in the absence of one, the other is mostly present in the form of homodimers instead of MT1/MT2 heterodimers, and that this homodimeric receptor configuration differentially guides melatonin signal transduction compared to MT1/MT2 heterodimers.

It appears that various central nervous system cells differentially express MT1 and MT2 receptors. For example, neurons in the Alzheimer’s hippocampus have an increased MT1/MT2 ratio (i.e., a shift towards MT1) compared with control neurons (Savaskan et al., 2002, 2005). Furthermore, the developing human brain primarily expresses MT1 with no or very few MT2 receptors (Thomas et al., 2002), and human CGC express MT1 but not MT2 mRNA (Al-Gholu et al., 1998). It is possible that such disease- or development-related alterations in melatonin receptor expression influence the effects of endogenous melatonin on neuronal ERK and Akt signaling. Generally, receptor-mediated effects of melatonin on neuronal ERK and Akt pathways may be involved in the modulation of mechanisms of neurodevelopment/neuroplasticity (Bordt et al., 2001) and neuroprotection (Kilic et al., 2005).

We also found that MT1/MT2 CGC respond to low nanomolar concentrations of melatonin with the typical inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP and cFos activation, which is indicative of the coupling of melatonin receptors to inhibitory G proteins. In fact, the involvement of G proteins in these effects was confirmed by our finding that this inhibitory action of melatonin was prevented by the pertussis toxin. Interestingly, under the same experimental conditions, melatonin was unable to affect cAMP levels and cFos immunoreactivity in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC. These latter data indicate that in the native environment of mouse CGC, the coupling of melatonin receptors to inhibitory G proteins appears to be functional only when both MT1 and MT2 are present. One possibility is that MT1/MT2 heterodimers (Ayoub et al., 2002, 2004) are essential to enable 1 nM melatonin to inhibit forskolin-stimulated cAMP and cFos signaling in mouse CGC but are not required to allow this low melatonin concentration to affect ERK activity. Whether higher concentrations of melatonin could affect cAMP and cFos in MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC should be further investigated.

The findings of our study may be a characteristic of mouse-CGC-specific cellular environment and/or G protein availability. In other words, experiments with transfected MT1 or MT2 receptors clearly demonstrated that MT1 and MT2 receptors, when expressed independently, in general are capable of coupling to inhibitory G proteins (Witt-Enderby et al., 1998; Kato et al., 2005). Transfection experiments also demonstrated that when expressed in the same cell type, MT1 and MT2 receptors may couple to different signaling patways (Petit et al., 1999).

It has to be acknowledged that, similar to the drawbacks in the models of heterologous receptor expression via transfection (Gabellini et al., 1994), the knockdown of native receptors may have also its shortcomings. Nevertheless, our studies demonstrated that in mouse CGC, native MT1 and MT2 receptors respond functionally to low nanomolar concentrations of melatonin. The full extent of the usefulness of MT1 CGC and MT2 CGC should be explored in future studies. For example, one possibility would be to use mouse MT1 CGC as a model for studying the effects of melatonin on human CGC, which are known to express MT1 but not MT2 mRNA (Al-Gholu et al., 1998).

4. Experimental procedures

4.1 Cerebellar granule cells (CGC) and treatment

Cultures were prepared from C3H mouse litters (wild-type [WT], and congenic C3H MT1- and MT2-knockout; the founder mice were provided by Drs. Reppert and Weaver of the University of Massachusetts Medical School). The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Primary CGC cultures were prepared from 5-day-old pups (Uz et al., 2001). CGC were grown in a serum-free medium (Neurobasal medium, GibcoBRL, Rockville, MD) and B27 supplement (GibcoBRL) in poly-D-lysine- (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) coated 3.5 cm-dishes (for Western blot assays), 24-well plates (for cAMP assays), and 24-well plates with 12 mm round cover glasses (immunohistochemistry assays). The density of cells was 0.6 million/ml (for the 3.5cm-dishes) and 400,000/ml (for the 24-well plates). Cultures were maintained for 8–10 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Melatonin (Sigma), forskolin (Sigma), and pertussis toxin (PTX; Sigma) were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma) and applied directly into the culture medium. Controls were treated with corresponding concentrations of DMSO. In the cAMP assay, forskolin was present for 10 min, melatonin was added to the medium 10 min prior to forskolin; PTX was added to the medium 16 h prior to melatonin and forskolin cotreatments. For cFos immunohistochemistry, cells were treated with forskolin for 2 h; for melatonin cotreatment, melatonin was administered 30 min prior to forskolin.

4.2. Western immunoblotting

Proteins were extracted from neurons plated in 3.5 cm dishes (3 dishes combined per sample). Cells were collected and homogenized in 100 μl/well of homogenizing buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis (beta-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid), 5mM EDTA (ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid), 2 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 0.2 units/ml aprotinin; 1.45 μM pepstatin A, 2.1 μM leupeptin, 5.7 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride) (pH 7.5) and 1X Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 2 (Sigma). After homogenization, samples were centrifuged for 10 min (1000 g, at 4°C) and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was measured using the Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL) BCA protein assay kit. Protein samples were processed on 7.5% (w/v) Tris-HCl gels. The proteins were transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Piscataway, NJ) for 3 h at room temperature (pAkt) or overnight at 4°C for pERK1/2. The blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with an anti-phospho-p44/42Map Kinase (ERK1/2) antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) or anti phospho-Akt Ser473 antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling). The blots were incubated with the appropriate horseradish-peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (1:1000 Amersham). To normalize the signals for pERK1/2 and pAkt proteins, the corresponding signals of total ERK1/2, and total Akt were measured on the same blots. The two bands of ERK immunoreactivity (ERK1 and ERK2) were analyzed together. An ECL Plus Kit (Amersham) was used for band visualization. The intensity of the bands was quantified using the Loats image analysis system (Loats Associates, Inc., Westminster, MD).

4.3 cAMP assay

The amount of cAMP was measured using the cAMP Biotrak competitive enzyme immunoassay system from Amersham as described by the manufacturer. The optical density of samples was measured at 630 nm and the concentration of cAMP was calculated from a standard curve (12.5–3,200 fmol), which was assayed along with the samples.

4.4. cFos immunohistochemistry

After drug treatment, the cultured cells on the cover glasses were fixed for 10 min in 4% (v/v) formaldehyde. Cells were treated overnight at 4°C with primary anti-cFos antibodies (1:4000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The cultures were washed and incubated for 1 h with biotinylated secondary antibody (1:250; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and washed again and incubated with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories) for 1 h. The cellular immunoreactivity of cFos was visualized by an application of 0.3 mg/ml 3-3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma) with 0.003% (v/v) of H2O2. The optical density (OD) of the immunolabeling was measured by capturing black and white images of the labeled cells using an AxioVision 3.1 microscope equipped with a camera (Carl Zeiss Vision, Jena, Germany). The immunostained cell nuclei were quantified by Scion Image software after capturing the images (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD). Before counting, each image was normalized adjusting the displayed grayscale range for that particular image. The average background OD in each visual field was subtracted from the individual cell OD measurements. Samples were taken from 10–15 random images, 200 × 270 μm, from each cover glass (200–250 total cells). For each experimental condition, we used 3–4 cover glasses and experiments were performed in 3 different culture preparations.

4.5. Statistical analysis

SPSS software (version 12.0) was used for data analysis. The immunoblot data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparison test or the t-test. An independent sample t-test was performed for the cAMP assay. cFos immunolabeling was analyzed by nested ANOVA. Results are presented as the mean ±SEM.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant R01 MH61572 (HM) and by the UIC Psychiatric Institute. We thank Drs. Reppert and Weaver of the University of Massachusetts Medical School for providing the MT1- and MT2-deficient founder mice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Ghoul WM, Herman MD, Dubocovich ML. Melatonin receptor subtype expression in human cerebellum. Neuroreport. 1998;9:4063–4068. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub MA, Couturier C, Lucas-Meunier E, Angers S, Fossier P, Bouvier M, Jockers R. Monitoring of ligand-independent dimerization and ligand-induced conformational changes of melatonin receptors in living cells by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21522–21528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub MA, Levoye A, Delagrange P, Jockers R. Preferential formation of MT1/MT2 melatonin receptor heterodimers with distinct ligand interaction properties compared with MT2 homodimers. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:312–321. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordt SL, McKeon RM, Li PK, Witt-Enderby PA, Melan MA. N1E-115 mouse neuroblastoma cells express MT1 melatonin receptors and produce neurites in response to melatonin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1499:257–264. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner P, Sozer-Topcular N, Jockers R, Ravid R, Angeloni D, Fraschini F, Eckert A, Muller-Spahn F, Savaskan E. Pineal and cortical melatonin receptors MT1 and MT2 are decreased in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Histochem. 2006;50:311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AS, Lai FP, Lo RK, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA, Stanbridge EJ, Wong YH. Melatonin mt1 and MT2 receptors stimulate c-Jun N-terminal kinase via pertussis toxin-sensitive and -insensitive G proteins. Cell Signal. 2002;14:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui P, Yu M, Luo Z, Dai M, Han J, Xiu R, Yang Z. Intracellular signaling pathways involved in cell growth inhibition of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2008;44:107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubocovich ML, Rivera-Bermudez MA, Gerdin MJ, Masana MI. Molecular pharmacology, regulation and function of mammalian melatonin receptors. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d1093–1108. doi: 10.2741/1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabellini N, Manev RM, Manev H. Is the heterologous expression of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) an appropriate method to study the mGluR function? Experience with human embryonic kidney 293 cells transfected with mGluR1. Neurochem Int. 1994;24:533–539. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti P, Gusella M, Lipartiti M, Milani D, Zhu W, Vicini S, Manev H. Melatonin protects primary cultures from kainite but not from N-methyl-D-aspartate excitotoxicity. Exp Neurol. 1995;131:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(95)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Jorge S, Guerrero JM, Jimenez-Caliani J, Naranjo MC, Lardone PJ, Carrillo-Vico A, Osuna C, Molinero P. Evidence for melatonin synthesis in the rat brain during development. J Pineal Res. 2007;42:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Hirai K, Nishiyama K, Uchikawa O, Fukatsu K, Ohkawa S, Kawamata Y, Hinuma S, Miyamoto M. Neurochemical properties of ramelteon (TAK-375), a selective MT1/MT2 receptor agonist. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic U, Kilic E, Reiter RJ, Bassetti CL, Hermann DM. Signal transduction pathways involved in melatonin-induced neuroprotection after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Pineal Res. 2005;38:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Jessen RE, Uz T, Arslan AD, Kurtuncu M, Imbesi M, Manev H. Impaired hippocampal long-term potentiation in melatonin MT2 receptor-deficient mice. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pääkkönen T, Mäkinen TM, Leppäluoto J, Vakkuri O, Rintamäki H, Palinkas LA, Hassi J. Urinary melatonin: a noninvasive method to follow human pineal function as studied in three experimental conditions. J Pineal Res. 2006;40:110–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit L, Lacroix I, de Coppet P, Strosberg AD, Jockers R. Differential signaling of human Mel1a and Mel1b melatonin receptors through the cyclic guanosine 3′-5′-monophosphate pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radio NM, Doctor JS, Witt-Enderby PA. Melatonin enhances alkaline phosphatase activity in differentiating human adult mesenchymal stem cells grown in osteogenic medium via MT2 melatonin receptors and the MEK/ERK (1/2) signaling cascade. J Pineal Res. 2006;40:332–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau A, Petrén S, Plannthin J, Eklundh T, Nordin C. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of melatonin: a pilot study in healthy male volunteers. J Neural Transmiss. 1999;106:883–888. doi: 10.1007/s007020050208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan E, Olivieri G, Meier F, Brydon L, Jockers R, Ravid R, Wirz-Justice A, Muller-Spahn F. Increased melatonin 1a-receptor immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Pineal Res. 2002;32:59–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan E, Ayoub MA, Ravid R, Angeloni D, Fraschini F, Meier F, Eckert A, Muller-Spahn F, Jockers R. Reduced hippocampal MT2 melatonin receptor expression in Alzheimer’s disease. J Pineal Res. 2005;38:10–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumaya IC, Masana MI, Dubocovich ML. The antidepressant-like effect of the melatonin receptor ligand luzindole in mice during forced swimming requires expression of MT2 but not MT1 melatonin receptors. J Pineal Res. 2005;39:170–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L, Purvis CC, Drew JE, Abramovich DR, Williams LM. Melatonin receptors in human fetal brain: 2-[(125)I]iodomelatonin binding and MT1 gene expression. J Pineal Res. 2002;33:218–224. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.02921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uz T, Giusti P, Franceschini D, Kharlamov A, Manev H. Protective effect of melatonin against hippocampal DNA damage induced by administration of kainate to rats. Neuroscience. 1996;73:631–636. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uz T, Manev R, Manev H. 5-Lipoxygenase is required for proliferation of immature cerebellar granule neurons in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;418:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00924-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uz T, Arslan AD, Kurtuncu M, Imbesi M, Akhisaroglu M, Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN, Manev H. The regional and cellular expression profile of the melatonin receptor MT1 in the central dopaminergic system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;136:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt-Enderby PA, Masana MI, Dubocovich ML. Physiological exposure to melatonin supersensitizes the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent signal transduction cascade in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing the human mt1 melatonin receptor. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3064–3071. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt-Enderby PA, Radio NM, Doctor JS, Davis VL. Therapeutic treatments potentially mediated by melatonin receptors: potential clinical uses in the prevention of osteoporosis, cancer and as an adjuvant therapy. J Pineal Res. 2006;41:297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YH, Zhou JN, Balesar R, Unmehopa U, Bao A, Jockers R, Van Heerikhuize J, Swaab DF. Distribution of MT1 melatonin receptor immunoreactivity in the human hypothalamus and pituitary gland: colocalization of MT1 with vasopressin, oxytocin, and corticotrophin-releasing hormone. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:897–910. doi: 10.1002/cne.21152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YH, Zhou JN, Van Heerikhuize J, Jockers R, Swaab DF. Decreased MT1 melatonin receptor expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]