Abstract

Chemotactic bacteria navigate their chemical environment by coupling sophisticated information processing capabilities to molecular motors that propel the cells forward. The ability to reprogram bacteria to follow entirely new chemical signals would create powerful new opportunities in bioremediation, bionanotechnology, and synthetic biology. However, the complexities of bacterial signaling and limitations of current protein engineering methods combine to make reprogramming bacteria to follow novel molecules a difficult task. Here we show that by using a synthetic riboswitch rather than an engineered protein to recognize a ligand, E. coli can be guided toward and precisely localized to a completely new chemical signal.

Introduction

Chemotactic bacteria navigate complex chemical environments by coupling sophisticated information processing capabilities to powerful molecular motors that propel the cells forward1-3. A general method to reprogram the ligand sensitivity of the bacterial chemo-navigation system would enable the production of cells that autonomously follow arbitrary chemical signals, such as pollutants or disease markers. Equipping bacteria that can degrade pollutants4, synthesize and release therapeutics5, or transport loads6 with the additional ability to localize to a specific chemical signal would open new frontiers in bioremediation, drug delivery, and synthetic biology. For example, such cells could be engineered to follow specific pollutants in soil and to degrade them. Alternatively, such cells could be engineered to selectively target small-molecule signals of disease, thus providing a powerful drug-delivery system7. However, the complexity of the bacterial chemosensory system makes reprogramming a cell to follow a completely new chemical signal a formidable challenge.

E. coli recognize chemoattractants using five transmembrane receptor proteins, which cluster with one another 8-11 and interact with a set of well characterized cytosolic proteins to effect changes in the directional rotation of the flagellar motor3,12. In the absence of a chemical gradient, individual E. coli execute a random walk characterized by smooth runs punctuated by tumbles that often result in a change of direction1-3. When a cell moves up a chemoattractant gradient, the flagellar motor preferentially rotates counterclockwise, resulting in less frequent tumbling and longer runs toward the attractant; when the chemoattractant concentration becomes constant, the cell resumes a random walk2. Similarly, when a cell moves down a chemoattractant gradient, the tumbling frequency increases. A defining feature of E. coli chemotaxis is that individual cells do not simply respond to the absolute concentration of a stimulus at a given time. Rather, individual E. coli cells integrate the concentration of a chemical stimulus over a 1-3 s period2 and migrate up attractant gradients by adjusting the frequency of tumbling based on the concentration differences between these time points.

In principle, bacteria can be programmed to respond to a new chemical signal by engineering an existing chemoreceptor protein to recognize a new ligand. Although E. coli have only 5 chemoreceptor proteins, they perform chemotaxis toward greater than 30 compounds1, indicating that some chemoreceptors recognize multiple compounds. A recent effort to engineer the tar (aspartate) receptor 13 produced relatively modest changes in ligand specificity, consistent with the tendency of engineered proteins to display broadened rather than shifted ligand specificities14,15. While it may be possible to produce more dramatic changes in receptor specificity using rational design, directed evolution13, or computational methods16, such efforts are ultimately limited by structural constraints enforced by the receptor scaffolds and the need to interface with the existing signaling network17. Thus, engineering cells to follow a new stimulus presents a difficult molecular recognition problem.

Faced with these challenges, we sought to bypass the chemoreceptors entirely by developing an effective, generic approach to reprogram E. coli to detect, follow, and localize to a new chemical signal. Over 40 years of genetics and biochemistry research has provided remarkable insight into the mechanisms of E. coli chemotaxis. The signal transduction pathway that converts ligand binding by the chemoreceptors into a change in the rotational direction of the flagellar motor is comprised of 6 chemotaxis proteins (Che A, B, R, W, Y, and Z).34 The chemoreceptors interact with CheB, R, and W, which collectively control the autophosphorylation rate of CheA, which in turn, phosphorylates the protein CheY. CheY controls the rotational direction of the flagellar motor. When CheY is phosphorylated (CheY-P), it binds to the flagellar switch protein FliM and induces the flagellum to rotate clockwise (CW), which causes the cell to tumble. Smooth swimming is restored by the phosphatase CheZ, which dephosphorylates CheY-P and causes the flagellum to rotate CCW (Figure 1, top). E. coli lacking the cheZ gene (ΔcheZ, strain RP1616) cannot dephosphorylate CheY-P, tumble incessantly, and are thus non-motile (Figure 1, bottom). Previous studies have shown that inducing the expression of CheZ can restore motility in a CheZ knockout strain by reactivating wild-type chemotaxis.18-20

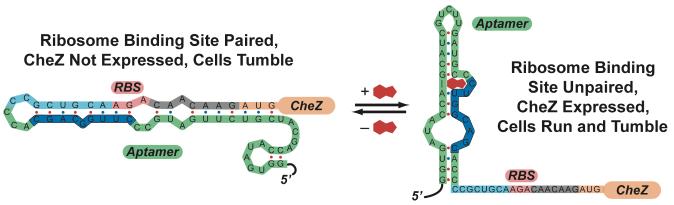

Figure 1.

top: Proteins involved in wild-type E. coli chemotaxis. The direction of rotation of the flagellar motor is controlled by the protein CheY. When CheY is not phosphorylated, the flagellar motor rotates clockwise (CW) and the cell runs for a period of 1-3 s. When CheY is phosphorylated (CheY-P), it can bind to the flagellar motor protein FliM, causing the cell to tumble. Wild-type E. coli can migrate on semi-solid agar (top right; cells grown for 10 h at 37 °C). bottom: Cells lacking the protein CheZ (strain RP1616) cannot dephosphorylate CheY-P and these cells tumble incessantly (bottom right; cells grown for 10 h at 37 °C). Cartoon adapted from reference (34).

We anticipated that using a ligand-inducible expression system to control the production of CheZ would enable us to guide cells toward higher concentrations of a new ligand in a process known as pseudotaxis21. This system would differ from classical E. coli chemotaxis in that cell motility toward the new ligand would be dictated by the absolute ligand concentration at a specific time, rather than the concentration differences between two points in time.

Key to these efforts is the development of a tunable ligand-inducible expression system that can precisely control the production of the CheZ protein. While a variety of bacterial expression systems are ligand-inducible, many of these, such as the lac repressor and the araC transcriptional regulator, use proteins to recognize ligands. Consequently, engineering these protein-based expression systems to respond to new ligands presents many of the same challenges that make engineering the chemoreceptor proteins difficult. In contrast to inducible expression systems that use proteins to recognize ligands, riboswitches22,23 control gene expression in a ligand-dependent fashion by using RNA aptamers to recognize ligands. Using powerful in vitro selection techniques24-26, it is possible to generate aptamers that tightly and specifically recognize new ligands without the need for a pre-existing RNA scaffold. We27,28, and others29-31, have shown that a variety of aptamers generated by in vitro selection can be engineered into synthetic riboswitches that regulate gene expression in a ligand-dependent fashion. Here we show that a synthetic riboswitch can guide E. coli toward a new, nonmetabolized ligand without protein engineering. These reprogrammed cells migrate preferentially up a ligand gradient and have the unique ability to localize to a specific chemical signal, which enables precise spatial patterning. We anticipate that the ability to engineer cells to follow new chemical signals will provide new opportunities in bioremediation and synthetic biology.

Results and Discussion

Since E. coli lacking a single gene in the signaling pathway (strain RP1616, ΔcheZ) tumble incessantly and are essentially non-motile (Figure 1, bottom)20, we first asked whether a synthetic riboswitch could restore ligand-dependent motility to E. coli RP1616 by activating the translation of CheZ in response to the alkaloid theophylline (Figure 2). Reprogramming a cell to follow theophylline is a challenging test: Theophylline is neither chemoattractive, nor extensively metabolized, and because it is structurally dissimilar to natural chemoreceptor ligands, which are predominantly amino acids, dipeptides, and sugars, it would be difficult to reengineer a chemoreceptor to selectively bind it.

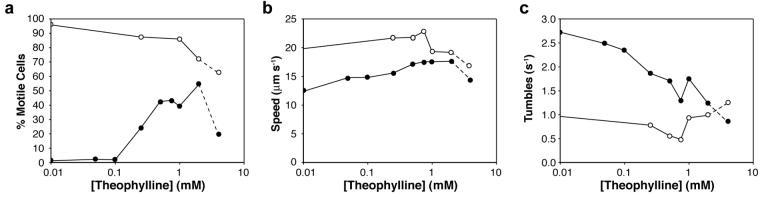

Figure 2.

Model for how the theophylline-sensitive synthetic riboswitch controls the translation of the CheZ protein. In the absence of theophylline (left), the mRNA adopts a conformation in which the ribosome binding site is paired and translation of CheZ is inhibited. In the absence of CheZ, the protein CheY-P remains phosphorylated and the cells tumble in place. In the presence of theophylline (shown in red), the mRNA can adopt a conformation in which the ribosome binding site is exposed and CheZ is expressed, thus allowing the cells to run and tumble. Model adapted from reference (28).

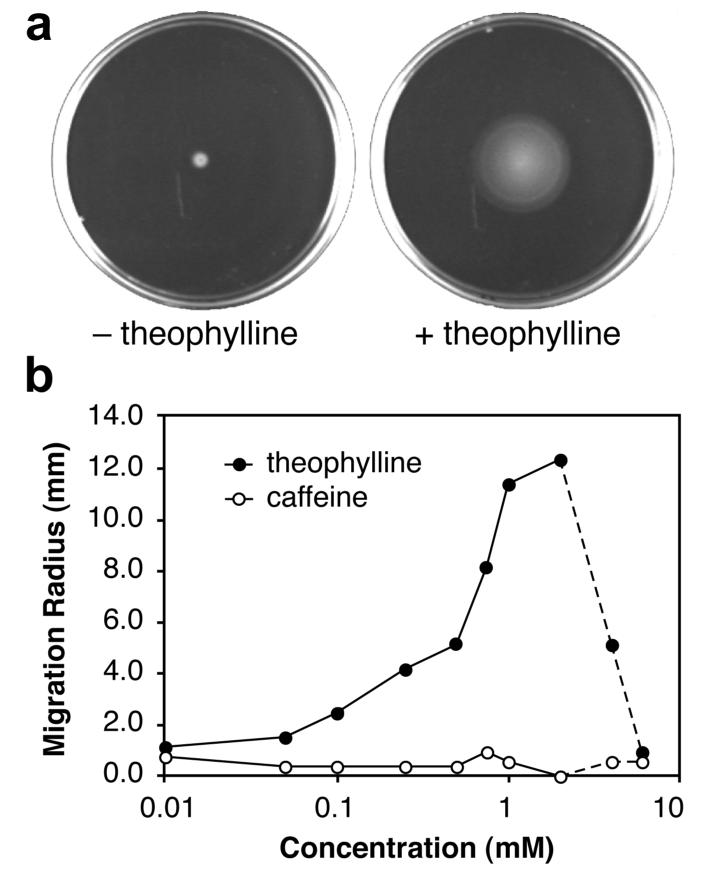

To investigate ligand-inducible motility, we introduced the cheZ gene under the control of a theophylline-sensitive synthetic riboswitch into E. coli RP1616 cells (hereafter referred to as “reprogrammed cells”), plated the reprogrammed cells onto semi-solid media containing various ligand concentrations, and measured their migration radius after 10 hours (Figure 3a). The distance that the cells migrated increased as a function of ligand concentration until reaching a maximum at 2mM theophylline, after which further concentration increases led to cell death (Figure 3b). When theophylline was replaced with caffeine, which is structurally similar, but does not bind to the riboswitch27, 28 the reprogrammed cells were non-motile (Figure 3b), demonstrating that motility changes are riboswitch-dependent.

Figure 3.

a. Migration of reprogrammed cells on semi-solid media in the absence or presence of theophylline (2 mM). b. Migration radius of reprogrammed cells as a function of ligand concentration. All cells were grown on semi-solid media for 10 h at 37 °C; uncertainties in measurement are smaller than the symbols.

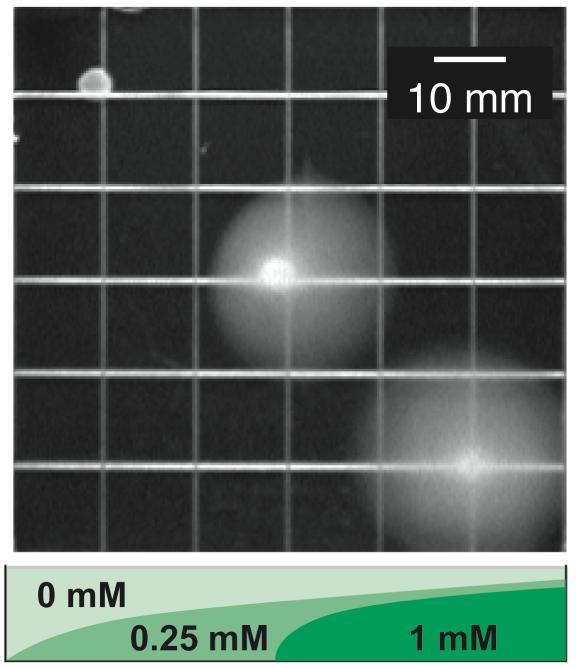

The increased migration of the reprogrammed cells at higher theophylline concentrations suggested that these cells might preferentially migrate up a theophylline gradient. To test this idea, we plated the reprogrammed cells at three locations on semi-solid media containing a theophylline gradient (Figure 4). Cells plated near the edges, where the local theophylline concentrations are relatively constant, do not bias their movement in a particular direction. In contrast, cells plated near the center of the plate experience larger changes in theophylline concentration over a short distance and bias their migration toward increasing theophylline concentrations. This behavior is consistent with the data in Figure 3b, in which significant changes in motility are observed in this concentration range.

Figure 4.

Migration of reprogrammed cells plated at three locations on semi-solid media containing a theophylline gradient. The layering scheme used to prepare the gradient and the theophylline concentrations are shown; cells were grown for 10 h at 37 °C.

Taken together, the data show that populations of reprogrammed cells recapitulate many features of chemotactic E. coli, including the ability to migrate up a ligand gradient. However, unlike wild-type E. coli, which rarely stop moving, populations of these engineered cells do not migrate in the absence of theophylline. To investigate the mechanisms that influence cell migration and to explain the phenotypic similarities and differences between the reprogrammed cells and wild-type E. coli, we assessed the ability of these cells to perform chemotaxis toward a natural chemoattractant in the presence of theophylline, as well as their ability to respond to various static concentrations of theophylline in the absence of chemoattractant gradients.

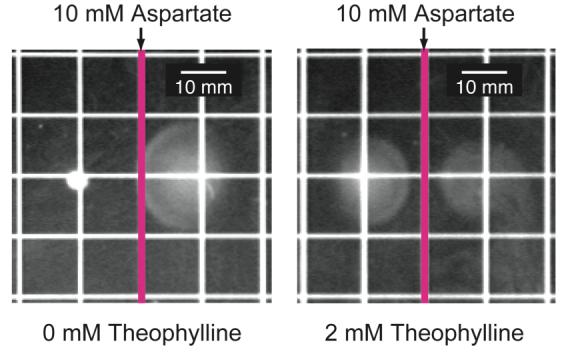

To determine if theophylline restored chemotaxis toward natural chemoattractants, we plated reprogrammed and wild-type cells onto semi-solid minimal-media plates that presented a gradient of the chemoattractant l-aspartate and a static theophylline concentration (0 or 2 mM). As expected, reprogrammed cells do not perform chemotaxis toward aspartate in the absence of theophylline (Figure 5). When theophylline is present, however, the reprogrammed cells perform chemotaxis toward aspartate in a manner similar to wild-type cells. Taken with the data in Figure 3b, these results indicate that the reprogrammed cells exhibit stronger chemotaxis toward natural chemoattractants at higher static theophylline concentrations, suggesting that the theophylline concentration may serve to establish the steady-state tumbling frequency of these cells. Thus, chemo-navigation is achieved, in part, because the riboswitch acts as a molecular brake. In the absence of theophylline, the brake is engaged and the reprogrammed cells tumble in place. Addition of theophylline releases the brake in a dose-dependent fashion by inducing the expression of CheZ, which allows the cells to navigate gradients of natural chemoattractants.

Figure 5.

Migration of reprogrammed (plated left of center) and wild-type cells (plated right of center) on minimal media containing a gradient of aspartate and a static concentration of theophylline (0 mM or 2 mM). Aspartate was applied to the surface of the plate along the pink line; theophylline was added to the media. Reprogrammed cells only perform chemotaxis when theophylline is present.

To investigate additional mechanisms influencing taxis, we used video microscopy to observe and track the motility of individual reprogrammed cells in rich liquid media containing various static theophylline concentrations.32,33 Since rich liquid media largely eliminates chemoattractant gradients, the effects of different theophylline concentrations can be studied independently of the gradient-induced chemotaxis that occurs on semi-solid media. The tracking data reveal that a prime determinant of the population behavior is a sharp concentration-dependent rise in the fraction of motile cells (Figure 6a). At low theophylline concentrations, most cells tumbled in place, consistent with the behavior of cells lacking CheZ. At higher concentrations, a greater fraction of the population was motile, consistent with theophylline-induced expression of CheZ and a transition from a tumbling to a running phenotype. These observations help explain both the theophylline-dependent increases in motility on semi-solid media (Figure 3b) and the gradient-sensing behavior seen in Figure 4.

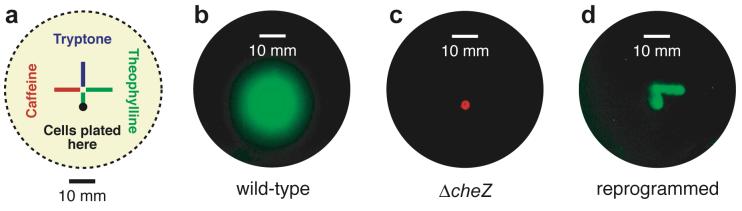

Figure 6.

a. Fraction of the population of cells that is motile for reprogrammed (solid circles) and wild-type cells (open circles) as a function of the theophylline concentration. b. Average run speeds of the motile fraction of the reprogrammed cells (solid circles) and wild-type cells (open circles). c. Average tumble frequencies of the motile fraction of the reprogrammed cells (solid circles) and wild-type cells (open circles). Dashes indicate theophylline toxicity.

To test whether motile cells exhibit pseudotaxis toward theophylline, we determined the average maximum run speeds (Figure 6b) and tumbling frequencies (Figure 6c) for the motile populations of the wild-type and the reprogrammed cells as a function of theophylline concentration. While motile cells from both strains showed modest theophylline-dependent changes in maximum run speed (Figure 6b), only the reprogrammed cells showed dramatic changes in tumbling frequency (Figure 6c). Whereas wild-type E. coli maintain a steady-state tumbling frequency of approximately 0.5 s−1 regardless of the absolute concentration of a chemoattractant18, reprogrammed cells adopt lower steady-state tumbling frequencies at higher theophylline concentrations, which allows cells to migrate up theophylline gradients via pseudotaxis.

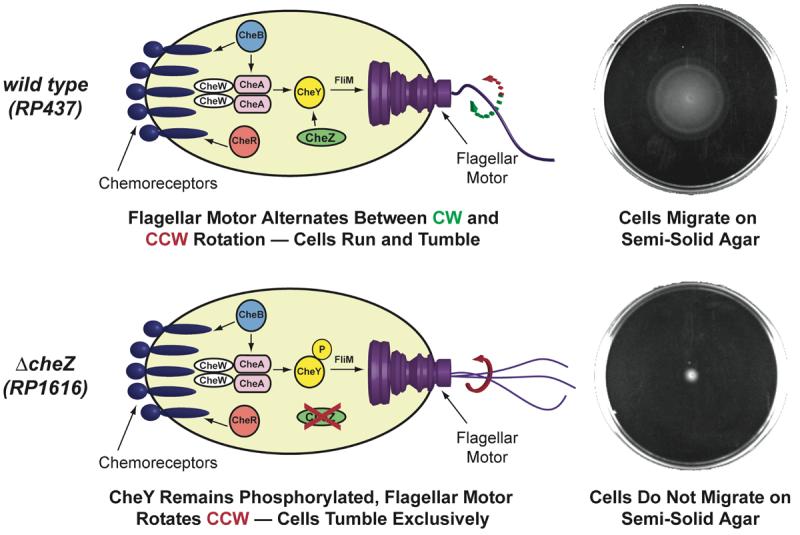

Since reprogrammed cells migrate further at higher ligand concentrations and essentially stop migrating at low concentrations, we anticipated that these cells might also navigate paths containing the ligand. To test this idea, we plated cells onto semi-solid media patterned with the various compounds shown in Figure 7a. Wild-type cells migrate radially without regard for the patterned compounds (Figure 7b), while RP1616 cells lacking the riboswitch are essentially non-motile (Figure 7c). In contrast, the reprogrammed cells exclusively follow the theophylline-containing path and eschew the other paths (Figure 5d). This behavior is possible because, unlike wild-type E. coli, reprogrammed cells become less motile as they move down a concentration gradient and, in the limit, are non-motile. Thus, these cells have the unique ability to localize to a specific target, which may be particularly useful for targeting cells to a specific disease site for applications in biomedicine.

Figure 7.

a. Diagram of plates containing semi-solid media patterned with solutions of various ligands. Cells were plated at the location shown and grown for 10 h at 37 °C. b. Motility of wild-type cells expressing GFP. c. Motility of RP1616 (ΔcheZ) cells expressing a red fluorescent protein. d. Motility of reprogrammed cells expressing GFP.

The reprogrammed cells described here capture many of the features displayed by naturally chemotactic bacteria such as gradient sensing, but do so through different mechanisms. Unlike natural chemotaxis in which cells detect gradients by integrating the concentration differences between chemoattractants at two points in time, reprogrammed cells respond to theophylline gradients via pseudotaxis, in which the motility of a cell changes as a function of the local theophylline concentration. Because motility changes are mediated through protein synthesis induced by the synthetic riboswitch, these cells respond to changes in the concentration of new ligands more slowly than wild-type cells, which respond to chemoattractants over a period of seconds by adjusting the methylation state and the degree of clustering of the chemoreceptor proteins. While the response rate of our reprogrammed cells to new ligands is slower than the natural chemotaxis response of E. coli, these cells show unique behaviors that are not displayed by wild-type bacteria. As an example, reprogrammed cells become less motile as the ligand concentration decreases, which allows these cells to not only detect gradients of a new ligand (Figure 4), but also to precisely target a patterned ligand (Figure 7). Finally, because the displacement of a reprogrammed cell is proportional to the ligand concentration and cells that migrate the farthest are easily identified in large populations, we anticipate that motility-based screens using synthetic riboswitches may provide a powerful and inexpensive technique to detect the production of small molecules through biocatalysis.

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrated that E. coli can be reprogrammed to detect, follow, and precisely localize to a completely new chemical signal by using a synthetic riboswitch, rather than a protein, to recognize a ligand. These reprogrammed cells not only retain the gradient sensing behavior of chemotactic E. coli, they also have the unique ability to localize to a specific chemical signal. Because ligand recognition in the reprogrammed cells is performed by RNA aptamers, which can be selected to recognize new compounds24-26 and incorporated into synthetic riboswitches using established methods27-31, we anticipate that it will be straightforward to reprogram bacteria to follow a variety of new ligands for applications in bioremediation and medicine. This new ability to equip motile bacteria with a precise and tunable chemo-navigation system greatly enhances the impressive arsenal of natural and engineered cell behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation and the NIH (GM074070) for financial support. S.T. is a George W. Woodruff Fellow, and J.P.G. is a Beckman Young Investigator. We thank Professor J.S. Parkinson for providing strains RP437 and RP1616; Professor Eric Weeks for helpful discussions and access to the video microscope and tracking software; and D. Lynn, C. MacBeth, I. Matsumura, W. Patrick for critical readings of the manuscript. DNA sequencing was performed at the Center for Fundamental and Applied Molecular Evolution (NSF-DBI-0320786).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Full experimental procedures and sample Quicktime movies of tracked bacteria. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Adler J. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1975;44:341–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:1024–37. doi: 10.1038/nrm1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkinson JS, Ames P, Studdert CA. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2005;8:116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis LB, Roe D, Wackett LP. Nucl. Acids Res. 2006;34:D517–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steidler L, Hans W, Schotte L, Neirynck S, Obermeier F, Falk W, Fiers W, Remaut E. Science. 2000;289:1352–5. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weibel DB, Garstecki P, Ryan D, Diluzio WR, Mayer M, Seto JE, Whitesides GM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11963–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505481102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JC, Clarke EJ, Arkin AP, Voigt CA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:619–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maddock JR, Shapiro L. Science. 1993;259:1717–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.8456299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bray D, Levin MD, Morton-Firth CJ. Nature. 1998;393:85–8. doi: 10.1038/30018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gestwicki JE, Kiessling LL. Nature. 2002;415:81–84. doi: 10.1038/415081a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sourjik V, Berg HC. Nature. 2004;428:437–41. doi: 10.1038/nature02406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker MD, Wolanin PM, Stock JB. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006;9:187–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derr P, Boder E, Goulian M. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:923–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumura I, Ellington AD. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:331–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aharoni A, Gaidukov L, Khersonsky O, Mc QGS, Roodveldt C, Tawfik DS. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:73–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Looger LL, Dwyer MA, Smith JJ, Hellinga HW. Nature. 2003;423:185–90. doi: 10.1038/nature01556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ames P, Studdert CA, Reiser RH, Parkinson JS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7060–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092071899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkinson JS, Houts SE. J. Bacteriol. 1982;151:106–13. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.106-113.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo SC, Koshland DE., Jr. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:1307–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1307-1314.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C, Stewart RC. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1202:297–304. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90019-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ames P, Yu YA, Parkinson JS. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;19:737–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.408930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR. Nature. 2002;419:952–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandal M, Breaker RR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:451–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuerk C, Gold L. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenison RD, Gill SC, Pardi A, Polisky B. Science. 1994;263:1425–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7510417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson DS, Szostak JW. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:611–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desai SK, Gallivan JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13247–13254. doi: 10.1021/ja048634j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynch SA, Desai SK, Sajja HK, Gallivan JP. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:173–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buskirk AR, Landrigan A, Liu DR. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suess B, Fink B, Berens C, Stentz R, Hillen W. Nucl. Acids Res. 2004;32:1610–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werstuck G, Green MR. Science. 1998;282:296–298. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alon U, Camarena L, Surette MG, Aguera y Arcas B, Liu Y, Leibler S, Stock JB. EMBO J. 1998;17:4238–48. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg HC, Brown DA. Nature. 1972;239:500. doi: 10.1038/239500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bren A, Eisenbach M. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6865–73. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.6865-6873.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.