Abstract

The folding of multidomain proteins often proceeds in a hierarchical fashion with individual domains folding independent of each other. A large single domain protein, however, can consist of multiple modules whose folding may be autonomous or interdependent in ways that are unclear. We use coarse-grained simulations to explore the folding landscape of the two-subdomain bacterial response regulator CheY. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization shows the landscape to be highly analogous to the four-state landscape reported for another two-subdomain protein, T4 lysozyme. An on-pathway intermediate structured in the more stable, nucleating subdomain was observed as well as transient states frustrated in off-pathway contacts prematurely structured in the weaker subdomain. Local unfolding, or backtracking, was observed in the frustrated state before the native conformation could be reached. Nonproductive frustration was attributable to competition for van der Waals contacts between the two subdomains. In the accompanying paper stopped-flow kinetic measurements support an off-pathway burst-phase intermediate, seemingly consistent with our prediction of early frustration in the folding landscape of CheY. Comparison of the folding mechanisms for CheY, T4 lysozyme and interleukin-1β leads us to postulate that subdomain competition is a general feature of large single domain proteins with multiple folding modules.

Keywords: protein folding, energy landscape, kinetics, multimodule proteins, topological frustration, coarse-grained molecular dynamics

Introduction

The mechanism by which a protein adopts its unique native fold remains a fundamental question in biology. Knowledge of the factors controlling how a polypeptide sequence dictates its own structure is not only necessary for efforts in structure prediction and protein design but will further our understanding of the thermodynamics governing protein stability and conformational dynamics. Failure of a protein to reach the native state can be deleterious. Partially unfolded or misfolded intermediates can lead to protein self-association and the formation of pathogenic oligomers and aggregates.1 A protein need not always fold to a well-structured, highly ordered native state, however. It has recently been discovered that large protein segments lacking a well-structured fold can also be functional. Intrinsically unstructured proteins contain highly conserved disordered regions that can be involved in target binding and recognition.2 In many disordered segments target binding can then induce a population shift to a well-structured fold. A fundamental step in understanding the conformational landscape of proteins as it relates to folding, aggregation and functional dynamics is the characterization of folding pathways and the nature of intermediates populated en route from the unfolded ensemble to the native state.

A number of experimental techniques have proven valuable for elucidating folding pathways. Phi-value analysis of mutations can determine which regions of a protein are natively structured in the folding transition state.3 Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and pulse-labeling hydrogen exchange have been used to monitor the development of site-specific structure in early kinetic intermediates during folding reactions.4–6 Rare thermodynamic intermediates have been probed using native state hydrogen exchange (NSHX), which reports on the structure of high-energy, partially unfolded conformations in equilibrium with the native state.7,8 Recently these techniques have been increasingly applied to large single domain proteins with complex folding mechanisms.9–13

The folding of multidomain proteins typically proceeds in a hierarchical fashion with individual domains folding independent of each other,14 which is important for evolutionary domain shuffling.15 A large single domain protein, however, can consist of multiple modules whose folding may be autonomous or interdependent in ways we are only beginning to understand.16 The 164-residue T4 lysozyme (T4L), for instance, consists of an α-helical C-terminal subdomain and a predominantly β-sheet N-terminal subdomain. NSHX has identified an on-pathway “hidden” intermediate structured in the C-terminus but unstructured in the N-terminus, the formation of which is the rate-limiting step in folding as illustrated by the cartoon in Fig. 1A.10–13,17 Isolated as fragments the C-terminus folds in absence of its partner subdomain whereas the N-terminus does not.11,18 The C-terminal subdomain thus serves as the folding nucleus in T4L with the N-terminus rapidly folding once it has formed.

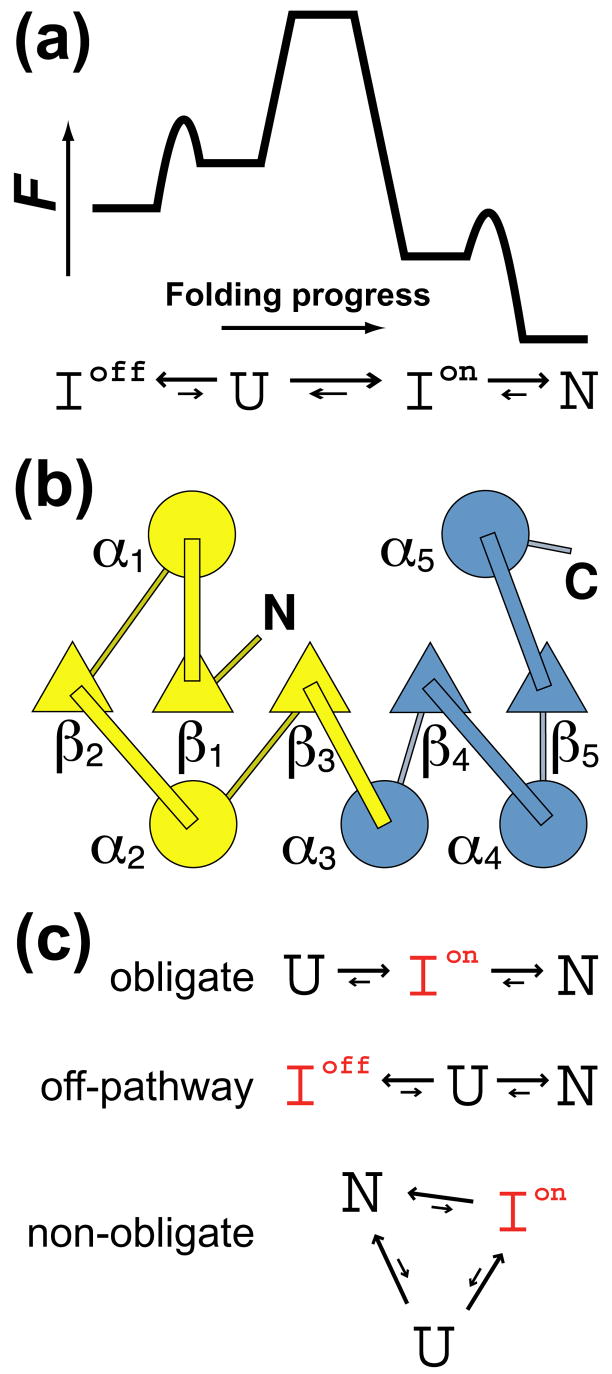

Fig. 1.

(a) Generic reaction diagram for four-state folding in proteins with competing subdomains. In T4 lysozyme, hydrogen exchange studies have identified a thermodynamic on-pathway intermediate with fully structured C-terminus but unstructured N-terminus and an early off-pathway kinetic intermediate partially structured in both terminii.10,13 (b) Topology of βα-repeat protein CheY with N-terminal (yellow) and C-terminal (blue) folding subdomains. (c) Three possible classifications for a folding intermediate: obligate on-pathway intermediate, misfolded off-pathway ‘trap’, or on-pathway intermediate in which the rate of direct transfer from U to N is nonnegligible.

Interestingly, pulse-labeling hydrogen exchange identified a second intermediate prior to the rate-limiting step in T4L folding. This kinetic intermediate formed rapidly (within the temporal resolution of the mixing device) and was partially structured in both subdomains.4,10 Since the N-terminus is unstructured in the on-pathway intermediate, the early intermediate must undergo an N-terminal unfolding event in order to proceed to the native state. Such transient formation of structure that must be undone prior to productive progression of folding to the native state constitutes off-pathway frustration, or “backtracking”, in the landscape.

Another multi-subdomain protein whose folding has been studied is 129-residue bacterial chemotactic response regulator CheY. A member of the second most common flavodoxin fold family, CheY consists of five β α-repeats arranged in a central parallel β-sheet surrounded by α-helices (Fig. 1B). Phi-value analysis has identified two folding subdomains in CheY: an N-terminal subdomain that is highly structured in the folding transition state and a C-terminal subdomain that is unstructured in the transition state.19 It has been observed that van der Waals contacts are weaker in the C-subdomain than the N-subdomain.19,20 Helix 4 lacks a strong N-capping residue and there is a cavity lined by several alanines between this helix and the rest of the protein, which gives rise to flexibility at the α4β5 surface of the protein. Cavity-filling mutants have demonstrated that this flexibility is important for function;21,22 upon phosphorylation of the loop connecting strand 3 and helix 3 the α4β5 surface undergoes a conformational rearrangement and binds downstream target FliM to modulate flagellar motility.23–25 The folding mechanism that has emerged for CheY is that the formation of the stable N-terminus is rate-limiting and serves to nucleate the weaker C-terminus.

In the present work we use molecular simulation to explore the landscape of subdomain folding in CheY. Our thermodynamic and kinetic characterization shows the landscape to be highly analogous to the four-state landscape of T4L and establishes a molecular basis for the four-state folding mechanism. Namely, the four-state-like landscape is a consequence of frustration caused by the competition for van der Waals contacts between the N- and C-terminal subdomains.

Our simulations employed the coarse-grained model developed by Karanicolas and Brooks for folding simulations.26 The protein is represented as a string of Cα beads that interact via a Gō-like potential in which only residue pairs that are in contact in the native state experience a pairwise attractive force. Gō models have been successful in reproducing the qualitative nature of folding transition states and intermediates for a range of proteins.27–32 This success is a consequence of protein folding landscapes being largely determined by the topology of the native state and having evolved to be dominated by native interactions.33 Non-native interactions, which can cause energetic frustration in the folding landscape, are generally responsible for minimal perturbations in the structure of transition states.28 Gō-like landscapes ignore non-native interactions and lack energetic frustration but may still contain frustration of another variety, which arises when native interactions form in the incorrect order. This type of frustration is dictated by the specific fold geometry and has been termed topological frustration.34,35 The authors note that frustration is a term used in physics in many different contexts; in this manuscript the term shall be reserved solely for signifying topological frustration in folding. Our present studies focus on topological frustration in the folding of CheY’s N-and C-terminal subdomains.

Results and Discussion

The sequence of events in CheY folding was mapped out by examining the dependence of the free energy on several structural properties. For such equilibrium thermodynamic calculations, multicanonical umbrella sampling was used to ensure the entire accessible landscape was sampled, including unfolded, native and high energy intermediate species. The authors note that more exact methods exist for characterizing the folding transition state ensemble;36–40 the goal of the present work was not to rigorously determine the structure of the transition state but rather to elucidate the folding mechanism of CheY by determining the most probable relative order of structure formation events. Multicanonical equilibrium simulations have proven useful in the study of complex folding behavior when multiple reaction coordinates are necessary to describe the essential features of folding mechanisms.28,41 To lend support to the mechanism established by our equilibrium simulations of the thermodynamic landscape, 100 independent, unbiased kinetic folding runs were also performed starting from a random coil unfolded structure under conditions promoting the native state. The relative sequence of folding events observed in the ensemble kinetic simulations was in good agreement with the most probable pathway revealed from thermodynamic landscape calculations.

N-terminal nucleation

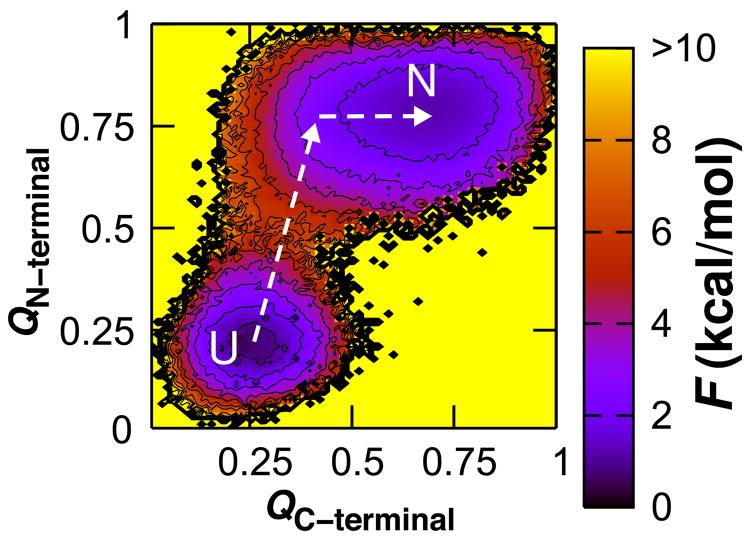

The free energy landscape was characterized at the folding transition temperature so that both the native and unfolded basins could be clearly defined. The fraction of native contacts formed, denoted Q, is a useful progress variable for monitoring the formation of secondary and tertiary structure.41–43 The free energy was computed as a function of the fraction of native contacts formed in the N- and C-terminal subdomains at the transition temperature (Fig. 2). The resulting Gō landscape agrees with experimental observations that the N-terminus is partially structured in the folding transition state whereas the C-terminus is not.19 The C-subdomain does not access its folded basin until the N-subdomain has folded and relies on contacts at the interface between the two subdomains for its stability, corroborating that the N-terminus serves as the folding nucleus. Additionally, the C-subdomain exhibited dynamic instability as evidenced by the large width of its native basin, visiting both structured and largely unstructured states within the native basin. C-terminal instability is not surprising given its deficiency in van der Waals contacts. Our Gō model assigned an average of 1.61 and 1.26 native contacts per residue in the N- and C-subdomains, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Thermodynamic characterization of the N-terminally nucleated folding landscape for CheY. The free energy is shown as a function of the fraction of native contacts formed within the N-terminal subdomain (QN-terminal) and the fraction of native contacts formed within the C-terminal subdomain (QC-terminal). Contours are drawn every kcal/mol; values exceeding 10 kcal/mol and regions not sampled are shown in yellow. This energy scale is used throughout the text. The free energy is computed at the folding transition temperature, here and throughout the text, such that the folded and unfolded states are equally populated.

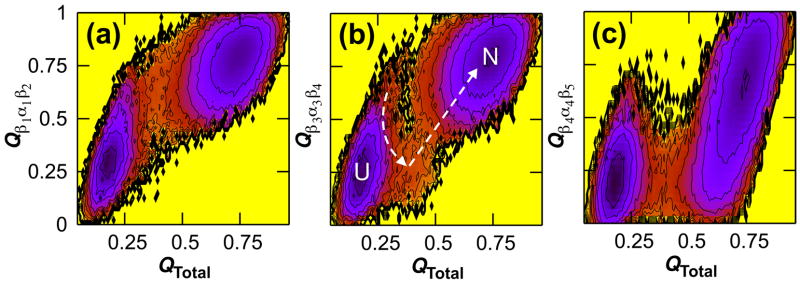

Additional insight into the sequence of folding events can be gained by looking at the formation of three topologically equivalent β α β motifs in CheY, which are centered at helices 1, 3 and 4. The three triads have 1.33, 1.07, and 0.83 contacts per residue and fold in order of decreasing contact density: 75% of contacts were satisfied for β1α1β2, β3α3β4, and β4α4β5 as early as QTotal = 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6, respectively (Fig. 3). The β4α4β5 region had the lowest contact density in the protein and the widest native basin, revealing that C-terminal instability originates in this functionally crucial segment that has been shown experimentally to be flexible in the inactive, unphosphorylated state.21,22 Fig. 3 also shows that elongation of the central β-sheet proceeds N-terminal to C-terminal. Further decomposition of the energy landscape shows that strands 1, 2 and 3 come together at approximately the same time in a concerted fashion, followed later by the addition of strand 4 and then finally strand 5 (see Fig. S1 in Supplementary Data).

Fig. 3.

Sequential assembly of three topologically equivalent triad segments within CheY. The free energy is shown as a function of the fraction of native contacts formed in the entire protein and within the regions spanning strands 1 and 2 and helix 1 (a), strands 3 and 4 and helix 3 (b), and strands 4 and 5 and helix 4 (c). Significant frustration is seen for the helix 3 triad, as evidenced by the high energy barrier bisecting the upper half of the pathway from U to N at QTotal = 0.37 (b).

Quasistable folding intermediate

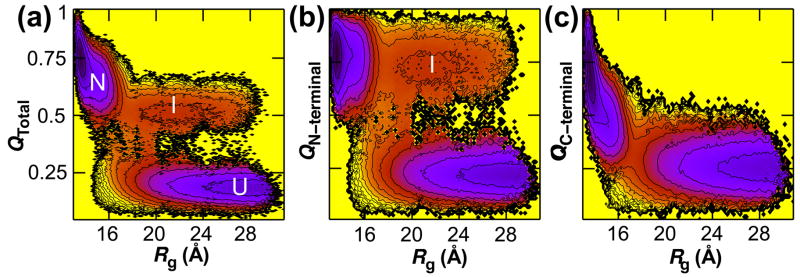

Projections of the folding landscape onto the structural progress coordinate radius of gyration, Rg, reveal the presence of a quasistable intermediate. Fig. 4 shows a shallow minimum at Rg = 22 Å, QTotal = 0.5 of depth ΔF = 0.8 ± 0.1 kcal/mol that corresponds to a structured N-terminus and unstructured C-terminus. Further analysis of the intermediate demonstrates that the interfaces between strands 3 and 4 and helices 2 and 3 are also formed (Fig. S2). The folding intermediate is thus structured in the region from strand 1 to strand 4 and shall henceforth be denoted Nheptad. Kinetic folding trajectories also confirm that the thermodynamic basin in Fig. 4A is Nheptad. To provide cross-validation between the multicanonical equilibrium simulations and ensemble kinetic simulations subsets of conformations sampled during kinetic folding simulations were extracted corresponding to four regions of interest in the thermodynamic landscape and the probability of formation was computed for various structural elements (Table 1). The third column of Table 1 confirms that the basin in question is structured from strand 1 to strand 4 in kinetic trajectories.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of a quasistable intermediate. The free energy is shown as a function of radius of gyration and the fraction of native contacts formed in the entire protein (a) and within the N- (b) and C-terminal (c) subdomains. The shallow basin at Rg = 22 Å, QTotal = 0.5 corresponds to an intermediate with a structured N-terminus and unstructured C-terminus.

Table 1.

Probabilities for formation of structural elements within subsets of conformations sampled during kinetic folding simulations

| Structural element | (Rg = 19 Å, QTotal = 0.37)a | (Rg = 21 Å, QTotal = 0.5) | (QTotal = 0.3, Qβ3α3β4 = 0.6) | (QTotal = 0.25, Qβ4α4β5 = 0.55) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.72 |

| α2 | 0.61 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 0.58 |

| α3 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.69 |

| α4 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.84 |

| α5 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.44 |

| β1–β2 b | 0.32 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| β1–β3 | 0.09 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| β3–β4 | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.03 |

| β4–β5 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.29 |

| α1–rest | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| α2–rest | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.06 |

| α3–rest | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.15 |

| α4–rest | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.21 |

| α5–rest | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| α1–α5 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| α2–α3 | 0.20 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.03 |

| α3–α4 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| β1α1β2 | 0.53 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| β3α3β4 | 0.43 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.30 |

| β4α4β5 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.51 |

| <Rg> (Å) | 19.1 | 21.4 | 26.5 | 28.9 |

The average fraction of native contacts formed for various structural elements was computed for conformations in kinetic simulations with 18 Å < Rg < 20 Å and 0.29 < QTotal < 0.42= 0.37, and similarly for the regions of conformational space specified in columns 3–5.

Dashes are used to denote native contacts between two elements of secondary structure: e.g., between strands 1 and 2 (β1–β2) or between helix 1 and the rest of the protein (α1–rest).

Incidentally, the structure of the folding transition state can be estimated from the second column of Table 1, which corresponds to the region in the vicinity of (Rg = 19 Å, QTotal = 0.37) in Fig 4A. The data in Table 1 corroborate that structure in the transition state is concentrated in the N-terminal subdomain; this is in qualitative agreement with experimental phi-values for CheY. If we compute the average phi-values reported by Lopez-Hernandez et al. for each element of secondary structure in CheY we have <φβ1> = 0.61, <φβ2> strand 2 = 0.82, <φβ3> strand 3 = 0.35, <φβ4> strand 4 = 0.03, <φβ5> strand 5 = –0.03, <φα1> helix 1 = –0.11, <φα2> helix 2 = 0.26, <φα3> helix 3 = –0.05, <φα4> helix 4 = –0.10 and <φα5> = 0.09.19 Hence it is evident that the transition state is partially structured in strands 1, 2 and 3 and helix 2 (the N-terminal subdomain) and unstructured in the C-terminal subdomain.

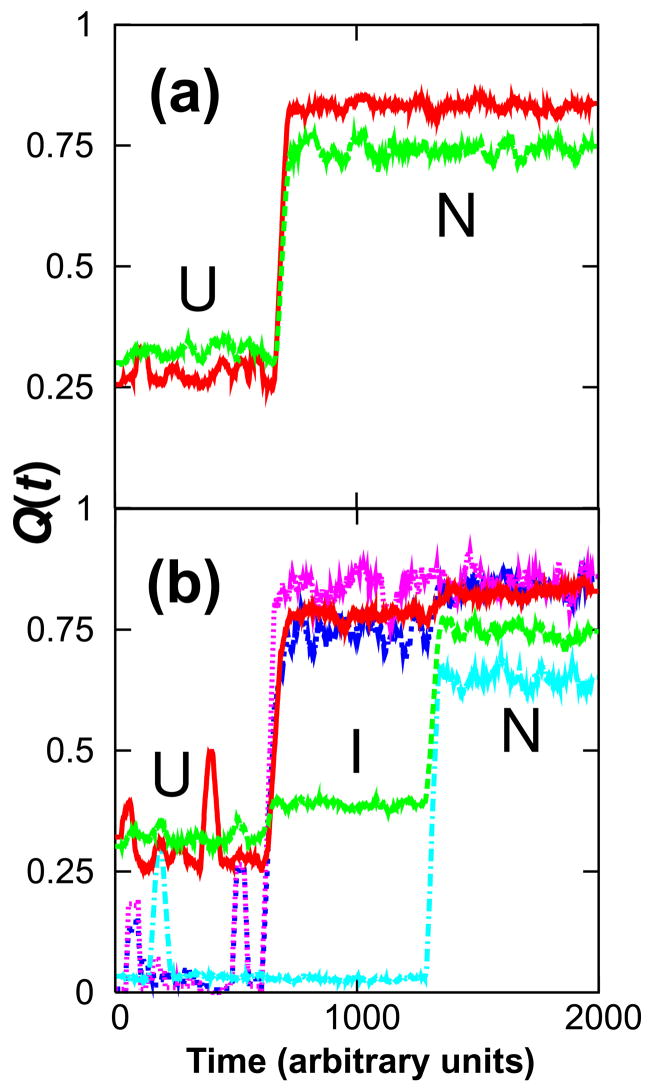

It is possible for trajectories to cross from U directly to N without getting stuck, even if only transiently, in the quasistable basin at Rg = 22 Å. Kinetic folding simulations corroborate that it is not necessary to populate a persistent Nheptad intermediate in passing from U to N (Fig. 5). Of the 100 independent kinetic runs performed, roughly half the trajectories passed directly form U to N and half proceeded via an Nheptad intermediate that persisted long enough to be observable. Nheptad can thus be regarded as a non-obligate, on-pathway intermediate.

Fig. 5.

Kinetic characterization of a non-obligate intermediate. The fraction of native contacts formed in the N- (red) and C-termini (green) is shown for two representative folding trajectories (a and b). Kinetic folding trajectories were equally likely to proceed through a long-lived intermediate (b) or to fold directly from U to N (a). The kinetic intermediate is Nheptad, as confirmed by the trajectory’s time courses for contacts formed between strands 3 and 4 (blue), helices 2 and 3 (pink), and helix 5 and the rest of the protein (cyan). For clarity, kinetic traces are shown as the moving average of 50 successive snapshots.

To determine the minimal folding fragment of CheY, unbiased single simulation folding runs were performed on seven N-terminal fragments of increasing length: β1α1β2, β1α1β2α2, … , (βα)4β5; which we denote N3, N4, … , N9. The simulations were ten times longer than the average time required for the full-length protein to fold, yet only fragments N7, N8 and N9 folded to a stable structure. This result is consistent with in vitro and in silico fragment studies on other proteins such as barnase and chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 that underscore the highly cooperative nature of folding.44–46 Also of note is that fragments N8 and N9 folded to a stable Nheptad structure but their respective C-terminal α4 and α4β5 regions were disordered. Nheptad is therefore analogous to the nearly self-sufficient C-terminal subdomain of T4L.11,18 C-terminal stability in T4L is not surprising given its N- and C-terminal subdomains have 1.3 and 1.9 native contacts per residue, respectively (as assigned by our Gō model to 2LZM.pdb). By comparison, CheY’s Nheptad and β4α4β5α5 regions have 1.7 and 1.1 native contacts per residue, respectively. For both proteins, the more stable subdomain serves as the nucleus around which the weaker terminus folds.

In the accompanying paper47 circular dichroism, intrinsic fluorescence and NMR spectroscopy were used to perform a global analysis of the overall folding mechanism for CheY. Inclusion of an off-pathway intermediate was needed to best explain the kinetic data. Testing an additional on-pathway intermediate was not possible with the model as it would lead to overparameterization of the system; thus it is unclear whether Nheptad should be truly regarded as an intermediate. In light of the marginal stability of the on-pathway Nheptad intermediate we have observed it could indeed alternatively be considered as part of a broad transition state ensemble.

In the case of CheY structural homolog apoflavodoxin, it has been remarked by Sancho and coworkers that the on-pathway folding intermediate is “useless but probably harmless.”48 Variants of apoflavodoxin have been observed to fit either the four-state linear mechanism of Fig. 1A or a three-state triangular mechanism (Fig. 1C), underscoring the precarious nature of intermediates in the flavodoxin fold family.48,49 The rate of transfer from Ion to N in the triangular mechanism of Anabaena apoflavodoxin was found to be sufficiently slow that Ion could essentially be regarded as an off-pathway intermediate. Incidentally, our Gō-like equilibrium landscape for CheY appears two-state when folding is monitored in one dimension along a single progress coordinate. No discernable intermediate is evident when the free energy is expressed as a one-dimensional function of the fraction of total native contacts formed nor from the temperature dependence of the heat capacity (Fig. S3). A growing line of evidence suggests that even in small proteins with apparent two-state folding, intermediates can be found once more precise experimental techniques are employed.50,51 Our observation of a triangular mechanism with an on-pathway, metastable intermediate lying in close proximity to the direct path from U to N offers one scenario in which an intermediate can be found in apparent two-state folding.

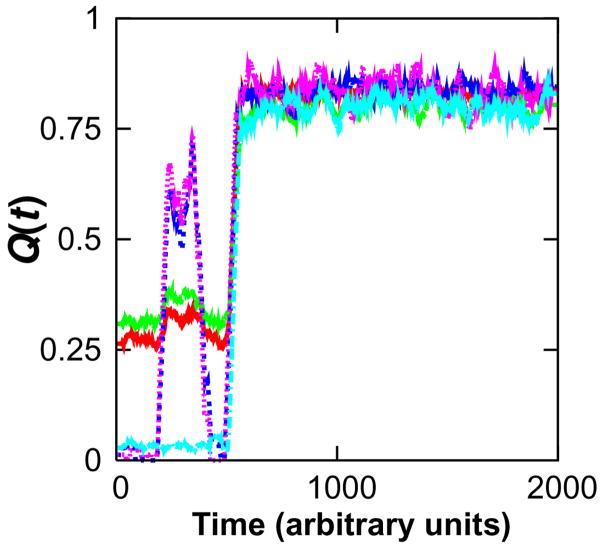

Topological frustration

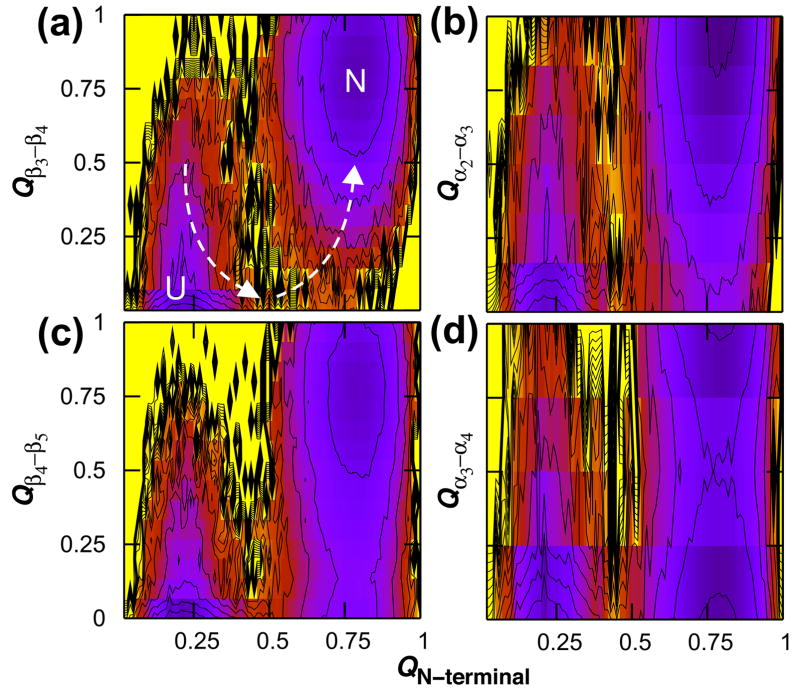

Frustration in the form of structurally localized off-pathway contacts is evident in the early stages of β3α3β4 folding, with the triad forming immediately from U but then backtracking while the N-terminal subdomain folds before proceeding on to the native state (Fig. 3B). Further decomposition of the landscape shows that backtracking during the formation of the N-terminal subdomain also occurs at the interface between helices 2 and 3 (Fig. 6B). Roughly one fourth of the kinetic simulations exhibited early frustration at the subdomain interface involving strands 3 and 4 and helices 2 and 3 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Frustration involving the C-terminus. The free energy is shown as a function of the fraction of native contacts formed in the N-terminus and between strands 3 and 4 (a), helices 2 and 3 (b), strands 4 and 5 (c), and helices 3 and 4 (d). N-terminal folding is seen to accompany an initial unfolding of contacts involving the C-terminus, as evidenced by the high energy barrier bisecting the path to N at QN-terminal = 0.4.

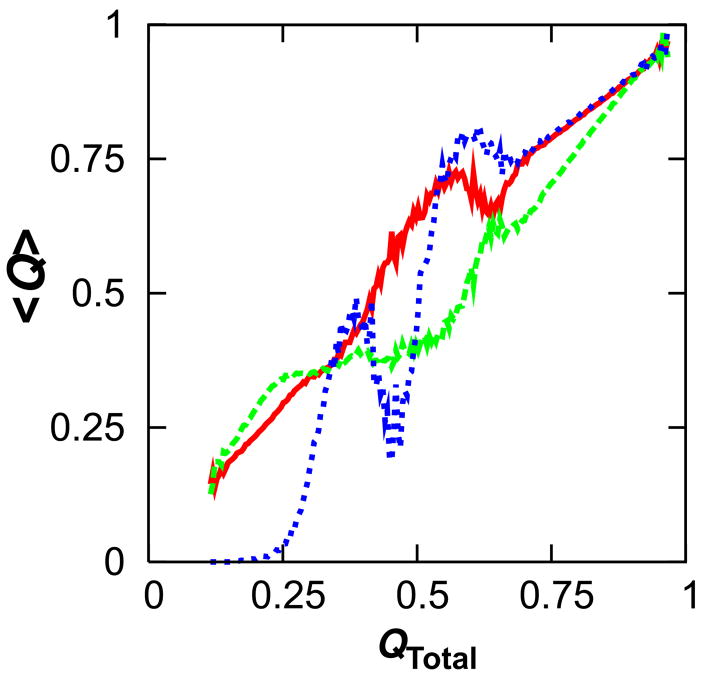

Fig. 7.

Example of a frustrated kinetic trajectory. The fraction of native contacts formed in the N- (red) and C-termini (green) and their interface is shown for a representative folding trajectory exhibiting frustration. The frustration is attributable to interfacial contacts not involving helix 5, as confirmed by the trajectory’s time courses for contacts formed between strands 3 and 4 (blue), helices 2 and 3 (pink), and helix 5 and the rest of the protein (cyan). On average, one out of every four folding simulations exhibited such frustration.

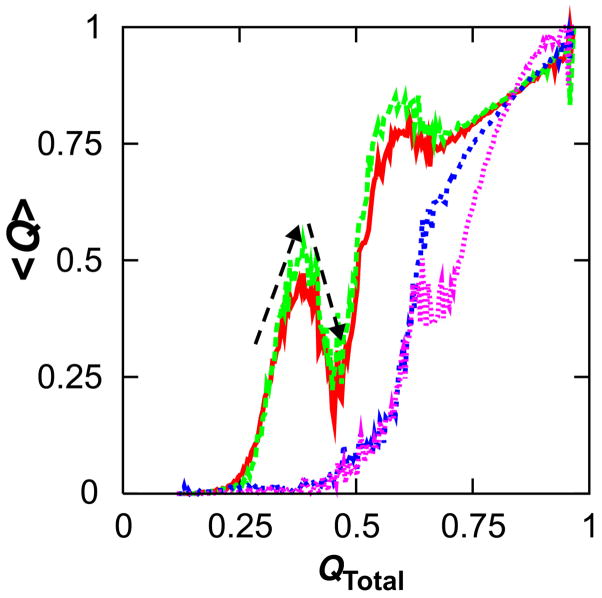

A small degree of frustration is also present within the C-terminal subdomain. Strands 4 and 5 and helices 3 and 4 transiently come together prior to N-terminal folding (compare Figs. 3C, 6C and 6D), but these species were not observable in the kinetic simulations. Fig. 8 shows that only interfacial frustration had a discernable influence on the overall ensemble-averaged kinetic time course, which we attribute to the greater density of contacts at the interface than within the C-subdomain. The negative slopes in the time courses at QTotal = 0.4 indicate local unfolding of interfacial contacts while N-terminal folding is still in progress. Note that the small negative slopes at QTotal = 0.6 correspond to a slight loosening of the structure prior to final maturation and are not to be confused with the more dominant early frustration. Subtle loosening of structure is often observed late in the folding of α-helices during the maturation of tertiary structure in our Gō model and has also been reported elsewhere.27

Fig. 8.

Influence of frustration on kinetics. The fraction of native contacts formed at each time point was computed for 100 independent folding simulations and ensemble-averaged. The mean fraction of contacts formed is shown as a function of the fraction of native contacts formed in the entire protein for contacts between strands 3 and 4 (red), helices 2 and 3 (green), strands 4 and 5 (blue), and helices 3 and 4 (pink). The large negative slopes at QTotal = 0.4 indicate local unfolding, or backtracking, of interfacial contacts not involving helix 5.

The cause of early frustration becomes more apparent in Fig. 9. An anticorrelation is initially observed between subdomain folding and interface formation. The initial burst in N-terminal folding at QTotal = 0.4 coincides with backtracking of interfacial contacts. The N-subdomain, with its greater density of native contacts, is outcompeting the α2β3α3β4 region for contacts and causing its local unfolding. Similarly, the main phase of C-terminal folding at QTotal = 0.6 is accompanied by a slight loosening of interfacial as well as N-terminal contacts prior to their final maturation. Hence, it is evident that topological frustration is the consequence of competition for N-terminal, C-terminal and interfacial native contacts.

Fig. 9.

Competition for interactions in kinetic simulations. The mean fraction of contacts formed is shown as a function of the fraction of native contacts formed in the entire protein for contacts in the N- (red) and C-termini (green) and their interface excepting helix 5 (blue). Note that the largest burst of N-terminal folding coincides with a decrease in interfacial contacts at QTotal = 0.4; additionally, the main phase of C-terminal contact formation at QTotal = 0.6 is accompanied by a small loss of N-terminal and interfacial contacts prior to their final maturation.

The reader may desire a better physical explanation for C-terminal frustration. The anticorrelation between subdomain and interfacial folding seen in Fig. 9 suggests that the act of contact formation in the N-subdomain exerts a kind of pulling force on the α2β3α3β4 interface, dislodging interfacial contacts in favor of the stronger N-terminal contacts. The inability of interfacial/C-terminal contacts to form at QN-terminal = 0.4 (Fig. 6) suggests that their formation is sterically precluded by the transition state structural ensemble for N-terminal folding, which is essentially an expanded version of the native N-subdomain (QN-terminal = 0.4, Rg = 18.8 Å). Loosening of preformed structure must therefore occur in order to access the folding transition state.

Topological frustration has recently been observed in interleukin-1β, a slow folder with low contact order.34 Interleukin-1β consists of three four-stranded β-trefoils, denoted N-terminal, central and C-terminal, that have 0.70, 0.89 and 0.73 native contacts per residue, respectively (as assigned by our Gō model to 6I1B.pdb). Gō-like simulations by Onuchic and colleagues show the central trefoil, with the most contacts, folds first and nucleates the N- and C-termini. Analogous to our results for CheY, backtracking was observed in the C-terminal trefoil during the main folding phase of the central trefoil. During the final stages of folding, a slight loosening was also observed in central contacts during the folding of the N- and C-termini, akin to what we have observed in CheY at QTotal = 0.6.

Two previous studies have reported backtracking in helices 4 and 5 of CheY. A Gō model study performed by Clementi et al. characterized an on-pathway intermediate and an earlier misfolded intermediate by generating contact probability maps for their corresponding structural ensembles.27 This study employed a simple Gō model in which all native contacts are assigned equal interaction strengths. It should be noted that in the present work the weighting of contact strengths in our flavored Gō model was rather uniform throughout CheY so our results can readily be compared to this earlier study. One notable difference between the two models, however, is that we do not employ a dihedral potential to bias torsional degrees of freedom to the native state. Clementi et al. observed an on-pathway intermediate unstructured in helices 4 and 5 but structured in helices 1, 2 and 3, which is consistent with our observation of Nheptad. Additionally, they observed an earlier misfolded intermediate that was structured in all five helices. Earlier experimental work by Lopez-Hernandez et al. demonstrated that helix propensity-enhancing mutants in CheY lead to a decrease in the rate of folding and also suggested that helices 3, 4 and 5 undergo a transition from structured to unstructured during folding.52

The structure of the folding transition state observed in the present work can be estimated from the second column of Table 1. If we compare the transition state to Nheptad (third column of Table 1), we indeed see backtracking in helices 4 and 5. Helices 4 and 5 have 0.63 and 0.52 probability of forming in the transition state, which is then reduced to 0.59 and 0.44, respectively, in the Nheptad intermediate. Kinetic backtracking in helices 4 and 5 is better illustrated when the mean fraction of contacts formed for all five helices is shown as a function of native contacts formed in the entire protein (Fig. S4). As hinted above, this subtle loosening of secondary structure late in folding is likely required for the maturation of tertiary structure and is not to be confused with the more dominant early frustration we have observed at the interface between the N- and C-terminal subdomains that is the focus of the present work. Experimental phi-value analysis using the method recently proposed by Weikl and Dill53 of decomposing helical phi-values into secondary and tertiary structure components could potentially shed additional light on the role of intrahelical versus interhelical frustration in CheY.

In the accompanying paper47 stopped-flow kinetic measurements support an off-pathway burst-phase intermediate formed within the dead time of the apparatus. The authors would like to point out that our Gō-like simulation results are not at odds with this and other reported experimental observations and, more importantly, provide a testable prediction. Perhaps pulse-labeling and native state hydrogen exchange studies such as those performed on T4L will be able to answer whether there is indeed an off-pathway burst-phase intermediate in CheY due to competition arising from the C-terminal subdomain.

Conclusion

We used a Gō-like coarse-grained model to explore the landscape of subdomain folding in β α-repeat protein CheY. The sequence of folding events we have observed can be summarized as follows. Strands 1, 2 and 3 of the central β-sheet align simultaneously and cooperatively. Formation of the N-terminal subdomain is followed by the formation of the β3α3β4 triad, which is then subsequently reinforced by formation of the helix 2-helix 3 interface. Next the β4α4β5 triad forms and is then reinforced by formation of the helix 3-helix 4 interface and the packing of helix 5 onto the N- and C-subdomains. The α2β3α3β4 tetrad causes frustration by transiently coming together prior to formation of the N-subdomain.

While direct paths are populated from U to N in a two-state-like fashion, monitoring the folding progress along multiple structural reaction coordinates enabled the detection of transient intermediate states. Analogous to the four-state folding mechanism in T4L, an on-pathway intermediate structured in the more stable subdomain was observed as well as states frustrated in off-pathway contacts prematurely structured in the weaker subdomain. These metastable intermediates were shown to be a consequence of competition for native contacts between the N- and C-subdomains. Functional requirements for flexibility, and hence a lower density of native contacts, in CheY’s C-terminus thus have a dramatic effect on the folding mechanism. Subdomain competition for interactions is evident in CheY, T4L and interleukin-1β, and we postulate this to be a general feature of large single domain proteins with multiple folding modules.

Materials and Methods

Coarse-grained model

We employed the coarse-grained model developed by Karanicolas and Brooks for folding simulations.26 The protein backbone is represented as a string of beads connected by virtual bonds. Each bead represents a single amino acid and is located at the α-carbon position. Bond lengths are kept fixed, bond angles are subject to a harmonic restraint and dihedral angles are subject to potentials representing sequence-dependent flexibility and conformational preferences in Ramachandran space. Nonbonded interactions are represented using a Gō model in which only residues that are in contact in the native state (taken to be crystal structure 3CHY.pdb) interact favorably. Backbone hydrogen bonds and sidechain pairs with nonhydrogen atoms separated by less than 4.5 Å interact via a pairwise potential that consists of an energy well and a small desolvation barrier. The interaction energies of sidechain native contacts are scaled according to their abundance in the Protein Data Bank as reported by Miyazawa and Jernigan.54 Residues not in contact in the native state interact via a repulsive volume exclusion term. We refer the reader to Karanicolas and Brooks26 for a complete description of the model potential and its parameters.

Simulation details

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed in Cartesian space using CHARMM55 within the gorex.pl module of the MMTSB Tool Set.56 Langevin dynamics with a 1.36 ps–1 friction coefficient was used to maintain thermal equilibrium and the time step was set at 22 fs. For kinetic folding simulations 100 independent runs were each performed for 2×108 dynamics steps at 0.87 Tf, where Tf is the folding transition temperature defined by the maximum in the heat capacity curve, Cv(T). The authors note that absolute timescales can not be obtained due to the coarse-grained nature of the Gō model and the lack of explicit solvent molecules. Unfolded starting structures for the folding runs were generated by equilibration at 1.5 Tf for 107 dynamics steps starting from randomly assigned initial velocities. Conformational snapshots were recorded every 105 dynamics steps. The fraction of native contacts formed, Q, was used to monitor folding progress. Each contact was considered formed if its residue pair was within a cutoff distance chosen such that the given contact is satisfied 85% of the time in native state simulations at 0.83 Tf.

Thermodynamic characterization

To characterize the entire accessible free energy landscape a two-dimensional extension of replica-exchange molecular dynamics57 was performed. Each replica was assigned one of four temperatures (0.87, 0.97, 1.08 or 1.20 Tf) and one of seven harmonic biasing restraints on the radius of gyration, Rg, for a total of 28 replicas. To ensure overlap between the Rg distributions harmonic potentials were used with minima at 1.0, 1.1. 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, 1.7 and 2.0 , where is the radius of gyration of the native state, with force constants 0.5, 5.0, 5.0, 5.0, 4.0, 0.8 and 0.5 kcal/mol-Å2, respectively. Stiff restraints were required at intermediate radii to sample the high energy transition region between the unfolded and native states. Conformational exchanges between temperature windows and restraints were attempted every 40,000 dynamics steps and the snapshots were recorded. The exchange frequency remained between ~10% and 40% throughout the 6×108-step simulation. Finally, conformations were combined from all 28 replicas for a total of 4.2×105 structures and the multidimensional weighted histogram analysis method58,59 was used to obtain the unbiased free energy at Tf projected along various progress coordinates. To ensure convergence of the results the above procedure was carried out twice.

Supplementary Material

Figures S1 to S4

Acknowledgments

R.H. thanks J. Karanicolas for technical assistance in implementing the coarse-grained model and D.A. Case for providing laboratory space. Simulations were performed using the modeling package available through the NIH resource (RR12255) Multiscale Modeling Tools for Structural Biology (mmtsb.org). We thank the NIH (GM48807) and the La Jolla Interfaces in Science Training Program (to R.H.) for financial support, the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (ctbp.ucsd.edu) for providing a stimulating intellectual environment, and S. Kathuria and C.R. Matthews for numerous insightful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thirumalai D, Klimov DK, Dima RI. Emerging ideas on the molecular basis of protein and peptide aggregation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:146–159. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fersht AR, Sato S. Phi-Value analysis and the nature of protein-folding transition states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7976–7981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402684101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu JR, Dahlquist FW. Detection And Characterization Of An Early Folding Intermediate Of T4 Lysozyme Using Pulsed Hydrogen-Exchange And 2-Dimensional Nmr. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4749–4756. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roder H, Elove GA, Englander SW. Structural Characterization Of Folding Intermediates In Cytochrome-C By H-Exchange Labeling And Proton Nmr. Nature. 1988;335:700–704. doi: 10.1038/335700a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Udgaonkar JB, Baldwin RL. Nmr Evidence For An Early Framework Intermediate On The Folding Pathway Of Ribonuclease-A. Nature. 1988;335:694–699. doi: 10.1038/335694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai YW, Sosnick TR, Mayne L, Englander SW. Protein-Folding Intermediates - Native-State Hydrogen-Exchange. Science. 1995;269:192–197. doi: 10.1126/science.7618079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bollen YJM, Kamphuis MB, van Mierlo CPM. The folding energy landscape of apoflavodoxin is rugged: Hydrogen exchange reveals nonproductive misfolded intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4095–4100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bueno M, Ayuso-Tejedor S, Sancho J. Do proteins with similar folds have similar transition state structures? A diffuse transition state of the 169 residue apoflavodoxin. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:813–824. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cellitti J, Bernstein R, Marqusee S. Exploring subdomain cooperativity in T4 lysozyme II: Uncovering the C-terminal subdomain as a hidden intermediate in the kinetic folding pathway. Protein Sci. 2007;16:852–862. doi: 10.1110/ps.062632807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cellitti J, Llinas M, Echols N, Shank EA, Gillespie B, Kwon E, Crowder SM, Dahlquist FW, Alber T, Marqusee S. Exploring subdomain cooperativity in T4 lysozyme I: Structural and energetic studies of a circular permutant and protein fragment. Protein Sci. 2007;16:842–851. doi: 10.1110/ps.062628607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato H, Feng HQ, Bai YW. The folding pathway of T4 lysozyme: The high-resolution structure and folding of a hidden intermediate. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H, Vu ND, Feng HQ, Zhou Z, Bai YW. The folding pathway of T4 lysozyme: An on-pathway hidden folding intermediate. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:881–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaenicke R. Stability and folding of domain proteins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1999;71:155–241. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doolittle RF. The Multiplicity Of Domains In Proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:287–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.001443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daggett V, Fersht AR. Is there a unifying mechanism for protein folding? Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llinas M, Gillespie B, Dahlquist FW, Marqusee S. The energetics of T4 lysozyme reveal a hierarchy of conformations. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/14956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llinas M, Marqusee S. Subdomain interactions as a determinant in the folding and stability of T4 lysozyme. Protein Sci. 1998;7:96–104. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LopezHernandez E, Serrano L. Structure of the transition state for folding of the 129 aa protein CheY resembles that of a smaller protein, CI-2. Fold Des. 1996;1:43–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson ED, Grishin NV. Alternate pathways for folding in the flavodoxin fold family revealed by a nucleation-growth model. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sola M, Lopez-Hernandez E, Cronet P, Lacroix E, Serrano L, Coll M, Parraga A. Towards understanding a molecular switch mechanism: Thermodynamic and crystallographic studies of the signal transduction protein CheY. J Mol Biol. 2000;303:213–225. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu XY, Rebello J, Matsumura P, Volz K. Crystal structures of CheY mutants Y106W and T871/Y106W - CheY activation correlates with movement of residue 106. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5000–5006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Formaneck MS, Ma L, Cui Q. Reconciling the "old" and "new" views of protein allostery: A molecular simulation study of chemotaxis Y protein (CheY) Proteins. 2006;63:846–867. doi: 10.1002/prot.20893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SY, Cho HS, Pelton JG, Yan DL, Henderson RK, King DS, Huang LS, Kustu S, Berry EA, Wemmer DE. Crystal structure of an activated response regulator bound to its target. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:52–56. doi: 10.1038/83053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stock AM, Guhaniyogi J. A new perspective on response regulator activation. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:7328–7330. doi: 10.1128/JB.01268-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., III The origins of asymmetry in the folding transition states of protein L and protein G. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2351–2361. doi: 10.1110/ps.0205402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clementi C, Nymeyer H, Onuchic JN. Topological and energetic factors: What determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and “en-route” intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:937–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., III Improved Go-like models demonstrate the robustness of protein folding mechanisms towards non-native interactions. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:309–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SY, Fujitsuka Y, Kim DH, Takada S. Roles of physical interactions in determining protein folding mechanisms: Molecular simulation of protein G and alpha spectrin SH3. Proteins. 2004;55:128–138. doi: 10.1002/prot.10576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutto L, Tiana G, Broglia RA. Sequence of events in folding mechanism: Beyond the Go model. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1638–1652. doi: 10.1110/ps.052056006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu L, Zhang J, Wang J, Li WF, Wang W. Folding behavior of ribosomal protein S6 studied by modified Go-like model. Phys Rev E. 2007;75 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.031914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koga N, Takada S. Roles of native topology and chain-length scaling in protein folding: A simulation study with a Go-like model. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:171–180. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gosavi S, Chavez LL, Jennings PA, Onuchic JN. Topological frustration and the folding of interleukin-1 beta. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shea JE, Onuchic JN, Brooks CL., Jr Exploring the origins of topological frustration: Design of a minimally frustrated model of fragment B of protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12512–12517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du R, Pande VS, Grosberg AY, Tanaka T, Shakhnovich ES. On the transition coordinate for protein folding. J Chem Phys. 1998;108:334–350. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubner IA, Deeds EJ, Shakhnovich EI. Understanding ensemble protein folding at atomic detail. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17747–17752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605580103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lam AR, Borreguero JM, Ding F, Dokholyan NV, Buldyrev SV, Stanley HE, Shakhnovich E. Parallel foldng pathways in the SH3 domain protein. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:1348–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimada J, Shakhnovich EI. The ensemble folding kinetics of protein G from an all-atom Monte Carlo simulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11175–11180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162268099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang JS, Wallin S, Shakhnovich EI. Universality and diversity of folding mechanics for three-helix bundle proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:895–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707284105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho SS, Levy Y, Wolynes PG. P versus Q: Structural reaction coordinates capture protein folding on smooth landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:586–591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509768103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shakhnovich E. Protein folding thermodynamics and dynamics: Where physics, chemistry, and biology meet. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1559–1588. doi: 10.1021/cr040425u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shakhnovich E, Farztdinov G, Gutin AM, Karplus M. Protein Folding Bottlenecks - A Lattice Monte-Carlo Simulation. Phys Rev Lett. 1991;67:1665–1668. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elcock AH. Molecular Simulations of cotranslational protein folding: Fragment stabilities, folding cooperativity, and trapping in the ribosome. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:824–841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ladurner AG, Itzhaki LS, Gay GD, Fersht AR. Complementation of peptide fragments of the single domain protein chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:317–329. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neira JL, Fersht AR. Exploring the folding funnel of a polypeptide chain by biophysical studies on protein fragments. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1309–1333. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kathuria SV, Day IJ, Wallace LA, Matthews CR. Kinetic traps in the folding of beta/alpha-repeat proteins: CheY initially folds to a well-structured off-pathway intermediate before back-tracking to reach the native conformation. J Mol Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.054. (co-submitted) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fernandez-Recio J, Genzor CG, Sancho J. Apoflavodoxin folding mechanism: An alpha/beta protein with an essentially off-pathway lntermediate. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15234–15245. doi: 10.1021/bi010216t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bollen YJM, Sanchez IE, van Mierlo CPM. Formation of on-and off-pathway intermediates in the folding kinetics of Azotobacter vinelandii apoflavodoxin. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10475–10489. doi: 10.1021/bi049545m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brockwell DJ, Radford SE. Intermediates: ubiquitous species on folding energy landscapes? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez IE, Kiefhaber T. Evidence for sequential barriers and obligatory intermediates in apparent two-state protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.LopezHernandez E, Cronet P, Serrano L, Munoz V. Folding kinetics of Che Y mutants with enhanced native alpha-helix propensities. J Mol Biol. 1997;266:610–620. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weikl TR, Dill KA. Transition-states in protein folding kinetics: The structural interpretation of phi values. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1578–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyazawa S, Jernigan RL. Residue-residue potentials with a favorable contact pair term and an unfavorable high packing density term, for simulation and threading. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:623–644. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. Charmm - A Program For Macromolecular Energy, Minimization, And Dynamics Calculations. J Comput Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feig M, Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., Jr MMTSB Tool Set: enhanced sampling and multiscale modeling methods for applications in structural biology. J Mol Graph. 2004;22:377–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugita Y, Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar S, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA, Rosenberg JM. The Weighted Histogram Analysis Method For Free-Energy Calculations On Biomolecules. 1. The Method. J Comput Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gallicchio E, Andrec M, Felts AK, Levy RM. Temperature weighted histogram analysis method, replica exchange, and transition paths. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:6722–6731. doi: 10.1021/jp045294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1 to S4