Abstract

The primate amygdaloid complex projects to a number of visual cortices, including area V1, primary visual cortex, and area TE, a higher order unimodal visual area involved in object recognition. We investigated the synaptic organization of these projections by injecting anterograde tracers into the amygdaloid complex of Macaca fascicularis monkeys and examining labeled boutons in areas TE and V1 using the electron microscope. The 256 boutons examined in area TE formed 263 synapses. Two hundred twenty-three (84%) of these were asymmetric synapses onto dendritic spines and 40 (15%) were asymmetric synapses onto dendritic shafts. Nine boutons (3.5%) formed double asymmetric synapses, generally on dendritic spines, and 2 (1%) of the boutons did not form a synapse. The 200 boutons examined in area V1 formed 211 synapses. One hundred eighty-nine (90%) were asymmetric synapses onto dendritic spines and 22 (10%) were asymmetric synapses onto dendritic shafts. Eleven boutons (5.5%) formed double synapses, usually with dendritic spines. We conclude from these observations that the amygdaloid complex provides an excitatory input to areas TE and V1 that primarily influences spiny, probably pyramidal, neurons in these cortices.

Keywords: primate, anterograde tracing, bouton, electron microscopy, connectivity

INTRODUCTION

The amygdaloid complex has been implicated in a number of behavioral functions. It has been consistently associated with a role in the perception of noxious or dangerous stimuli and the orchestration of the resulting emotional response (LeDoux et al., 1990; Adolphs et al., 1994; Armony, 1999; Aggleton, 2000; LeDoux, 2000; Emery et al., 2001; Prather et al., 2001; Bauman et al., 2004; Mason et al., 2005). The amygdala has a rich complement of connections through which it can influence sensory processing, motor function and visceral and autonomic responses (Amaral et al., 1992). In the primate, the amygdala is interconnected with widespread areas of the neocortex, including the ventral stream visual processing pathway (Mizuno et al., 1981; Tigges et al., 1982; Tigges et al., 1983; Amaral and Price, 1984; Iwai and Yukie, 1987; Amaral et al., 2003; Freese and Amaral, 2005). The ventral stream or “what” visual processing pathway, which consists in the macaque monkey of areas V1, V2, V4, TEO, and TE, is involved in object recognition and processes information such as shape and color (Ungerleider, 1982). Area TE of this system gives rise to a heavy projection to the amygdala which terminates mainly in the dorsal portion of the lateral nucleus (Stefanacci and Amaral, 2000; Stefanacci and Amaral, 2002). We (Emery et al., 2001; Prather et al., 2001; Bauman et al., 2004; Freese and Amaral, 2005) and others (Adolphs et al., 1994; Adolphs et al., 1995; Morris et al., 1998; Armony, 1999; LeDoux, 2000; Davis and Whalen, 2001; Vuilleumier et al., 2001; Vuilleumier et al., 2004) have speculated that once the amygdala is in receipt of visual information from area TE, it carries out an evaluation of the relative danger of the perceived stimulus. The mechanisms through which the amygdala orchestrates an escape response are not well established.

The amygdala also projects back to the visual cortex. It gives rise to pathways that extend throughout the full rostrocaudal extent of the ventral visual processing stream (Tigges et al., 1982; Tigges et al., 1983; Amaral and Price, 1984; Iwai and Yukie, 1987; Amaral et al., 2003; Freese and Amaral, 2005). The projections follow a rostrocaudal topographic organization such that more rostral aspects of the amygdala project preferentially to more rostral visual areas and more caudal parts of the amygdala project preferentially to more caudal visual areas (Amaral and Price, 1984; Iwai and Yukie, 1987; Amaral et al., 2003; Freese and Amaral, 2005). These projections are organized in a feedback-like fashion in that they terminate in the superficial and deep layers of area TE and in the superficial layers of area V1 (Freese and Amaral, 2005).

Few studies have probed the ultrastructural organization of the primate amygdaloid connections. Electron microscopy has been used to examine some intrinsic and cortical connections of the rodent (Kita and Kitai, 1990; Stefanacci et al., 1992; Bacon et al., 1996; Savander et al., 1997) and cat (Smith and Paré, 1994; Paré et al., 1995b; Smith et al., 2000) amygdaloid complex. Limited work in the primate has examined the synaptic organization of projections to the amygdala from the orbitofrontal cortex (Leichnetz et al., 1976; Smith et al., 2000). Pitkänen and colleagues determined that most of the projections from the amygdala to the entorhinal cortex form asymmetric axospinous synapses onto dendritic spines (Pitkänen et al., 2002). No other analysis has been performed on connections between the amygdala and neocortex in primates, so details concerning the synaptic organization of primate amygdalo-cortical connections are unavailable.

Knowledge about the synaptic organization of projections from the amygdala to visual cortices would contribute to the development of functional hypotheses concerning these projections. What types of synapses do these projections form? What are the postsynaptic targets of the amygdaloid fibers? Beginning to provide information about these issues was the major goal of this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A detailed description of the experimental animals, surgical and injection procedures, histological processing, and procedures for light microscopic analysis has been published in Freese and Amaral (2005). An abridged version of the procedures is presented here.

Animals

Four adult macaque monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) of either sex and weighing between 2.93 and 3.80 kg at the time of surgery were the subjects of this study. All experimental procedures were carried out under an approved University of California, Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol and strictly adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines on the use of non-human primate subjects.

For the surgeries, animals were brought to a surgical level of anesthesia, placed in a Kopf stereotaxic apparatus and a 2.5% solution of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin (PHA-L) or a 10% solution of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) was iontophoretically injected into the magnocellular and intermediate divisions of the basal nucleus of the amygdala. Postoperatively, the monkeys received analgesics as necessary and prophylactic doses of antibiotics.

Histological Procedures

Two different fixation protocols were used on these animals. After a 12 to 14 day survival period, 2 of the animals (M4-90 and M5-97) were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer. The brain was then blocked stereotaxically in the coronal plane, postfixed, and put into a solution containing 10% glycerol and 2% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) followed by 20% glycerol and 2% DMSO. The brain was rapidly frozen and sectioned at a thickness of 30 mm. Sections were stored in a cryoprotectant tissue collecting solution at −70°C until processed immunohistochemically for visualization of PHA-L or BDA.

Two of the animals (M1-03 and M2-03) were prepared specifically for electron microscopy and fixed accordingly. Following a 12 to 14 day survival period, the animals were perfused with cold 0.9% NaCl solution followed by solutions of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer, postfixed for 2 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer, and cryoprotected as above except no DMSO was included. The brains were rapidly frozen in isopentane and stored at −70°C until cut into 30 mm sections in the coronal plane on a freezing microtome.

Immunohistochemical Procedures

Light Microscopy

A 1-in-8 series of sections was rinsed in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffered saline (KPBS, pH 7.4) and pretreated with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide then washed again in KPBS. For PHA-L processing, non-specific staining was blocked with Normal Goat Serum (NGS) to which 0.5% Triton X-100 (TX-100) was added in KPBS. The sections were then incubated in a primary antiserum for 48 hours at 4°C. Following washes in 2% NGS, the tissue was placed in secondary antiserum, washed in NGS in KPBS, then incubated in avidin-biotin complex (ABC) in KPBS. The sections were rinsed in NGS, returned to the secondary antiserum, rinsed in KPBS, then incubated in ABC. The sections were rinsed in KPBS, then in 0.05 M Tris hydrochloride buffer (pH 7.4) and immersed in 3′3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) in hydrogen peroxide in Tris buffer. To halt the reaction, the tissue was washed several times in Tris buffer, then in KPBS, then mounted onto gelatin-coated slides. Sections were intensified with silver nitrate and gold chloride, then coverslipped with DPX (BDH Laboratory Supplies, Poole, UK).

For BDA, sections were pretreated as above. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in a solution of ABC and TX-100 in KPBS. The sections were rinsed in Tris buffer and incubated in a DAB-peroxidase solution. Sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides and the mounted sections were then intensified and coverslipped as described above.

Electron Microscopy

All incubations were carried out with free-floating sections at room temperature with constant agitation unless otherwise specified. The sections were rinsed in KPBS and pretreated in 1% sodium borohydride for 20 minutes to decrease non-specific antibody binding, followed by additional rinses in KPBS. For PHA-L processing, non-specific staining was blocked with 5% NGS in KPBS. The sections were then incubated in a primary antiserum solution (rabbit anti-PHA-L, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA; 1:1,000 dilution) containing 2% NGS in KPBS. Following washes in KPBS, the tissue was placed in secondary antiserum (biotinylated goat anti-rabbit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame CA, USA; 1:200 dilution) in KPBS for 90 minutes. Washes in KPBS were followed by an incubation in ABC (Biomedia Biostain Super ABC Kit, Biomedia, Foster City, CA, USA) in KPBS. The sections were rinsed in KPBS, then rinsed in 0.05 M Tris buffer and immersed in DAB in Tris buffer for 20 minutes at room temperature. To halt the reaction, the tissue was washed several times in Tris buffer, then in KPBS, and embedded in araldite resin.

For BDA, pretreated sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in a solution of ABC in KPBS. The sections were then rinsed in KPBS then in Tris buffer and incubated in DAB in Tris buffer. Sections were rinsed twice in Tris buffer, once in KPBS, and embedded in araldite resin.

Embedding for Electron Microscopy

Based on the light microscopic analysis of adjacent sections (see below), regions of areas TE and V1 containing many PHA-L or BDA labeled axons and terminals were washed in Zetterquist wash solution (pH 7.4: 9.4 mM Sodium Chloride, 0.18 mM Calcium Chloride, 0.37 mM Potassium Chloride in a sodium acetate buffer; Pease, 1964). Sections were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 20 minutes, washed 3 × 5 minutes in Zetterquist wash solution, dehydrated in 50% then 70% ethanol, and placed in 3% uranyl acetate in 70% ethanol for 1 hour to improve contrast. Sections were dehydrated through a series of alcohols (5 minutes each in 70%, 80%, 95%, 100% 3 times), further dehydrated in 100% propylene oxide 3 times for 5 minutes, soaked in a 1:1 solution of 100% propylene oxide and araldite resin for 4 hours, then immersed in pure resin overnight. The sections were incubated 2 times for 2 hours each in pure araldite resin, then placed between 2 sheets of Aclar film (Ted Pella, Inc, Redding, CA, USA) and cured at 60°C for 48 hours.

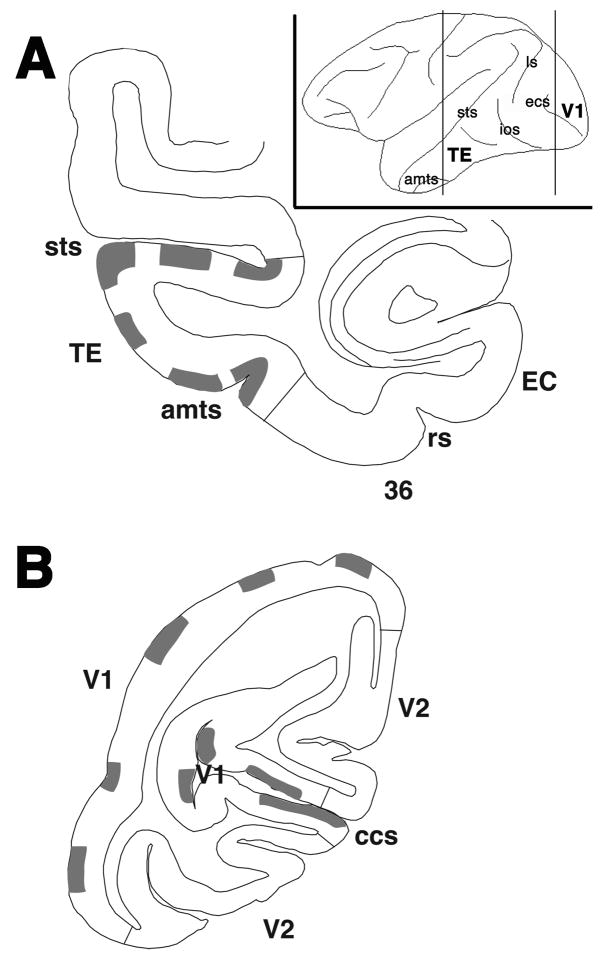

Sections were examined with a light microscope and regions containing PHA-L or BDA labeled fibers and terminals were chosen for electron microscopic analysis. While we selected areas with high concentrations of labeled boutons, care was taken to sample all regions of areas TE and V1 (Fig 1). Amygdaloid projections terminate in the superficial and deep layers of area TE and the superficial layers of area V1 (Amaral and Price, 1984; Freese and Amaral, 2005). For a more direct comparison of amygdaloid boutons in these two areas, only terminals in the superficial layers was investigated. Blocks were serially sectioned with a Leica UCT ultramicrotome into 70 nm sections based on the interference color of the floating sections (Meek, 1976). The sections were positioned onto 1 mm slotted, piloform-covered (Marivac Limited, Quebec, Canada), copper coated grids (Ted Pella, Inc, Redding, CA, USA), stained with 8% uranyl acetate in distilled water for 20 minutes, washed with distilled water, stained with 0.4% lead citrate for 2 minutes, and again washed with distilled water.

Figure 1.

Line drawings representing a section in (A) area TE and (B) area V1. The approximate locations of regions chosen for electron microscopic analysis are identified by gray shading in both areas. While only one rostrocaudal plane is illustrated here, EM analysis was performed along the entire rostrocaudal extent of both areas. The insert demonstrates the lateral surface of the brain depicting the rostrocaudal locations of the represented area TE and V1 sections.

Histological Analysis

Electron Microscopy

Ultrathin sections were scanned at 80 kV with either a Zeiss 10 transmission electron microscope (TEM) or a Philips CM 120 TEM. Once a putative PHA-L or BDA labeled bouton was found, it was photographed at 20,000x or 21,500x magnification in every serial section in which it could be identified. Some micrographs were taken with a conventional camera. These negatives were scanned into a Power Macintosh G3 computer with a Polaroid SprintScan 45 Pro scanner at 1000 dpi. Most of the labeled boutons were imaged digitally with a 2K × 2K element CCD camera (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA) attached to the electron microscope and processed using DigitalMicrograph Software (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA). For all digitized images, levels, brightness, and contrast were adjusted using Adobe Photoshop to obtain uniformity and optimal visualization.

Identification of Synaptic Junctions

A potential synapse was examined in serial sections to assist in the characterization of the synapse type and postsynaptic component. Labeled potential boutons were only counted when at least 3 synaptic vesicles were present. Synapses were identified by the presence of a postsynaptic density and clear pre- and post-synaptic membranes separated by a synaptic cleft. The postsynaptic component was identified (see below) and the synapses were characterized as asymmetric or symmetric. An asymmetric synapse was distinguished by the presence of round synaptic vesicles and a proportionately thicker postsynaptic density while a symmetric synapse was distinguished by flattened synaptic vesicles and pre- and post-synaptic densities that were roughly similar in thickness (Gray, 1959). During the analysis we noted if the postsynaptic density (PSD) appeared to be macular or perforated. One hundred amygdaloid boutons in area TE and 100 amygdaloid boutons in area V1 were randomly selected for volumetric measurement. The volumes of these boutons were measured according to the Cavalieri principal (Gundersen and Jensen, 1987; West and Gundersen, 1990). Every section (0.07 mm apart) in which a particular labeled bouton appeared was used for the measurement of its volume.

Identification of the Postsynaptic Component

We attempted to identify each postsynaptic component that received a synapse from an amygdaloid terminal. In some cases, the dendritic spine could be followed back to its parent dendrite, providing an unequivocal classification. Generally, however, we relied on the established ultrastructural characteristics of spines in order to make a decision of whether the postsynaptic element was a spine or a dendritic shaft. A dendritic spine is identified by the lack of microtubules, neurofilaments, mitochondria, and ribosomes (although the latter two can occasionally be found in spines), and the presence of a spine apparatus and “fluffy” fine filaments (Peters et al., 1991). A dendritic shaft is identified by the presence of multiple organelles including microtubules, neurofilaments, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum (Peters et al., 1991).

RESULTS

Nomenclature

The definition of amygdaloid nuclei and areas TE and V1 can be found in Freese and Amaral (2005).

Description of Injection Sites

The PHA-L and BDA injection sites were identified under brightfield and darkfield illumination by the clustering of labeled cell bodies (Fig. 2A). The locations of injections used in this paper were illustrated in Freese and Amaral (2005) and are briefly described below. Taken together, they sampled much of the caudal half of the dorsal extent of the basal nucleus. Experiment M5-97 had a PHA-L injection that involved the middle and caudal levels of the intermediate and magnocellular divisions of the basal nucleus and the lateral nucleus. The PHA-L injection in experiment M1-03L involved the middle and caudal aspects of the intermediate and magnocellular divisions of the basal nucleus and included the lateral and accessory basal nuclei as well. Experiment M4-90 contained a caudally-placed PHA-L injection that involved the magnocellular division of the basal nucleus and the lateral nucleus. Experiment M1-03R had a caudal injection of BDA focused in the magnocellular division of the basal nucleus. Experiment M2-03R had a BDA injection into caudal aspects of the intermediate and magnocellular divisions of the basal nucleus and also involved the accessory basal nucleus. Finally, experiment M2-03L had a PHA-L injection that involved caudal aspects of the amygdala, focused in the intermediate and magnocellular divisions of the basal and lateral nuclei.

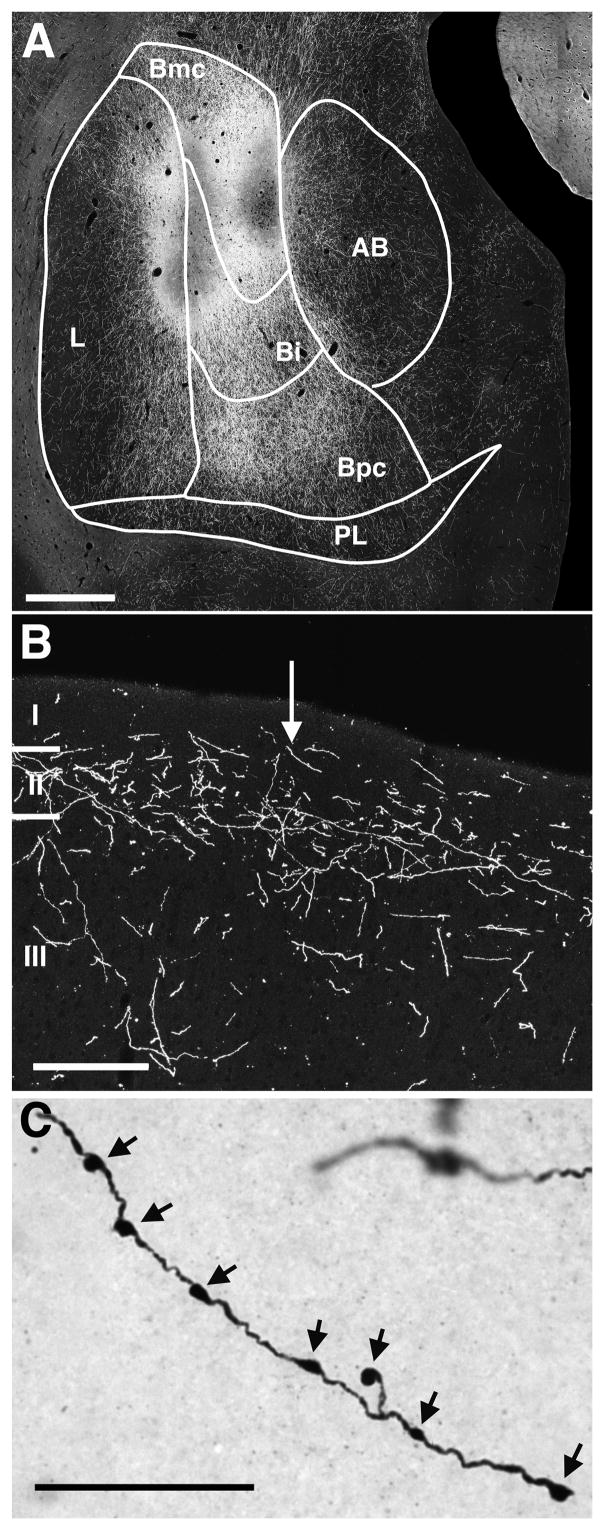

Figure 2.

(A) A darkfield photomicrograph of a representative injection site. This PHA-L injection from case M1-03L was focused on the intermediate and magnocellular divisions of the basal nucleus and included the lateral and accessory basal nuclei as well. (B) A darkfield photomicrograph of a labeled fiber plexus in the superficial layers of area TE. Fibers are varicose and tend to run parallel to the pial surface. Layers I-III are indicated. (C) A high magnification brightfield photomicrograph of the fiber indicated by the arrow in (B). The arrows point to varicosities along the fiber. Scale bars: A = 250 μm, in B = 100 μm, and in C = 25 μm.

Light Microscopy

Details concerning the projections from the amygdala to visual cortices have been published (Freese and Amaral, 2005), so only a brief description will be provided here. It should be noted that BDA is sometimes transported in the retrograde as well as the anterograde direction (Sidibe et al., 1997; Reiner et al., 2000). In our BDA experiments, we never observed labeled cell bodies or dendrites. We have consistently found that BDA is a reliable anterograde marker and in our hands does not get transported retrogradely to any significant extent in the nonhuman primate. Fibers from the amygdala traveled to areas TE and V1 in what we have named the temporal-occipital amygdalo-cortical pathway (TOACP). Projections to both areas are characterized by the presence of numerous varicose fibers (Fig. 2B–C). The magnocellular and intermediate divisions of the basal nucleus of the amygdala gave rise to heavy projections throughout the rostrocaudal extent of area TE. The projections terminated both in superficial layers, specifically the border of layers I/II, and in deep layers (V and VI). While most of the injections led to heavier fiber and terminal labeling in the superficial layers of area TE, the most dorsal injections in the basal nucleus produced denser labeled fibers and terminals in the deep layers of area TE.

Area V1 received projections primarily from the magnocellular division of the basal nucleus. As in area TE, projections from the amygdala to area V1 were distributed throughout its rostrocaudal extent. These projections terminated exclusively at the layer I/II border.

Electron Microscopy

Technical considerations

The goal of this study was to label amygdaloid varicosities located in areas TE and V1 in order to elucidate the synaptic organization of these projections. The advantage of the tracer injection and immunohistochemical procedure we used was the definitive identification of amygdaloid terminals. However, this technique also has disadvantages. The DAB reaction product was quite dense and limited some of the quantitative measurements. For example, the reaction product could conceal the dense core vesicles we sometimes observed in the boutons, and so it was difficult to accurately quantify the total number of dense core vesicles. Furthermore, the integrity of membranes was sometimes compromised by the immunohistochemical processing. Due to such limitations, we took a conservative approach to identifying synapses. We required that both a pre- and a post-synaptic membranes were clearly visible and that a clear postsynaptic density was present. Boutons that contained vesicles but did not have a visible postsynaptic density were counted as not forming a synapse. The examination of serial sections aided our identification of synapses by providing multiple sections in which a potential synapse could be viewed. Because of our strict criteria, some labeled synapses likely were not counted, and it is possible that the percentage of boutons that form multiple synapses is higher than we report. However, we are confident that we have greatly reduced false-positives and that this conservative approach provides a representative description of the amygdalocortical synapses.

Morphology of Labeled Terminals

PHA-L and BDA labeled structures were identified easily at the electron microscopic level by the presence of amorphous, electron-dense DAB reaction product (Fig. 3). The reaction product varied in intensity, filled the cytoplasm of terminals, and typically was closely associated with the vesicles and mitochondria.

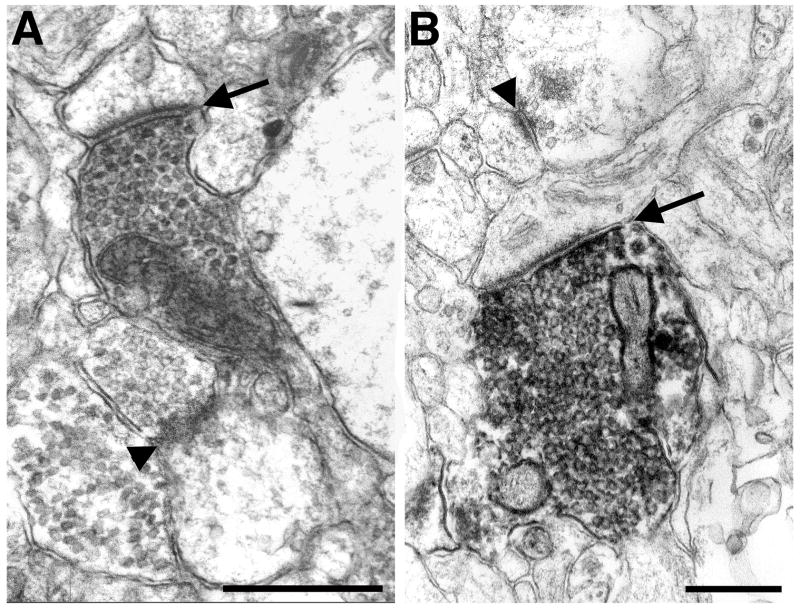

Figure 3.

Electron micrographs of labeled amygdaloid terminals forming asymmetric axospinous synapses in area TE. PHA-L and BDA labeled boutons are identified by the dark, amorphous, electron-dense DAB reaction product. Unlabeled boutons (arrowheads) have a clear cytoplasm. Both amygdaloid boutons contain round synaptic vesicles and a single mitochondrion. The thickened postsynaptic densities (arrows) indicate that both synapses are asymmetric. Scale bar: 0.5 μm.

In general, amygdaloid terminals in areas TE and V1 were indistinguishable. We never observed myelinated labeled axonal fibers, which suggests that the segments of the amygdalo-cortical fibers that innervate the cortex are not myelinated. However, we did not survey the labeled fibers along their course from the amygdala to the cortex.

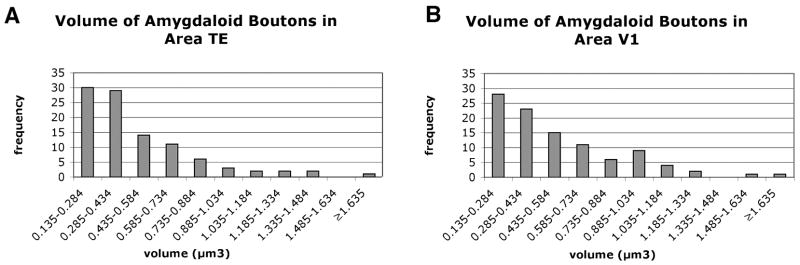

Amygdaloid boutons were generally spherical or ovoid in shape. The synaptic vesicles within these boutons were typically clear and round. Mitochondria were the most common organelle and were present in 59.7% of the boutons (see Fig. 3). Small holes or vacuoles sometimes were found in the axon terminals. These small regions were devoid of reaction product, tissue, or even embedding medium (see Fig. 5 for an example). This is likely an artifact of the DAB labeling that has been noted in other studies (LeVay, 1986; Anderson et al., 1998). Based on measurements of 100 boutons in each area, the volume of boutons in area TE ranged from 0.142–1.790 μm3 (Mean = 0.480 μm3), and in area V1 ranged from 0.135–1.714 μm3 (Mean = 0.526 μm3 - Fig. 4).

Figure 5.

Electron micrographs of 2 amygdaloid boutons each forming 2 asymmetric, axospinous synapses. The arrows point to the postsynaptic densities and “v” indicates small vacuoles that are an artifact of the DAB labeling process. Scale bar: 0.5 μm.

Figure 4.

Graphs of the frequency distribution of bouton volumes in (A) area TE and (B) area V1.

Area TE

We examined 256 labeled amygdaloid boutons in area TE. These formed 263 synapses, including 9 boutons that formed double synapses (Fig. 5) and 2 boutons that did not form a synapse. All of the synapses were asymmetric and contained round, clear vesicles and a thickened postsynaptic density. Approximately 27% of the postsynaptic densities were perforated, but most were continuous (compare perforated synapse in Fig. 6 with continuous synapses in Figs. 3 and 5). Most (223; 84.2%) of the axonal terminals were in synaptic contact with dendritic spines (Fig. 6). Of the 223 spines that received a synapse from an amygdaloid bouton, 13 (5.8%) received a second synapse from an axonal terminal of unknown origin. Forty (15.1%) of the amygdaloid boutons formed synapses onto dendritic shafts (Fig 7).

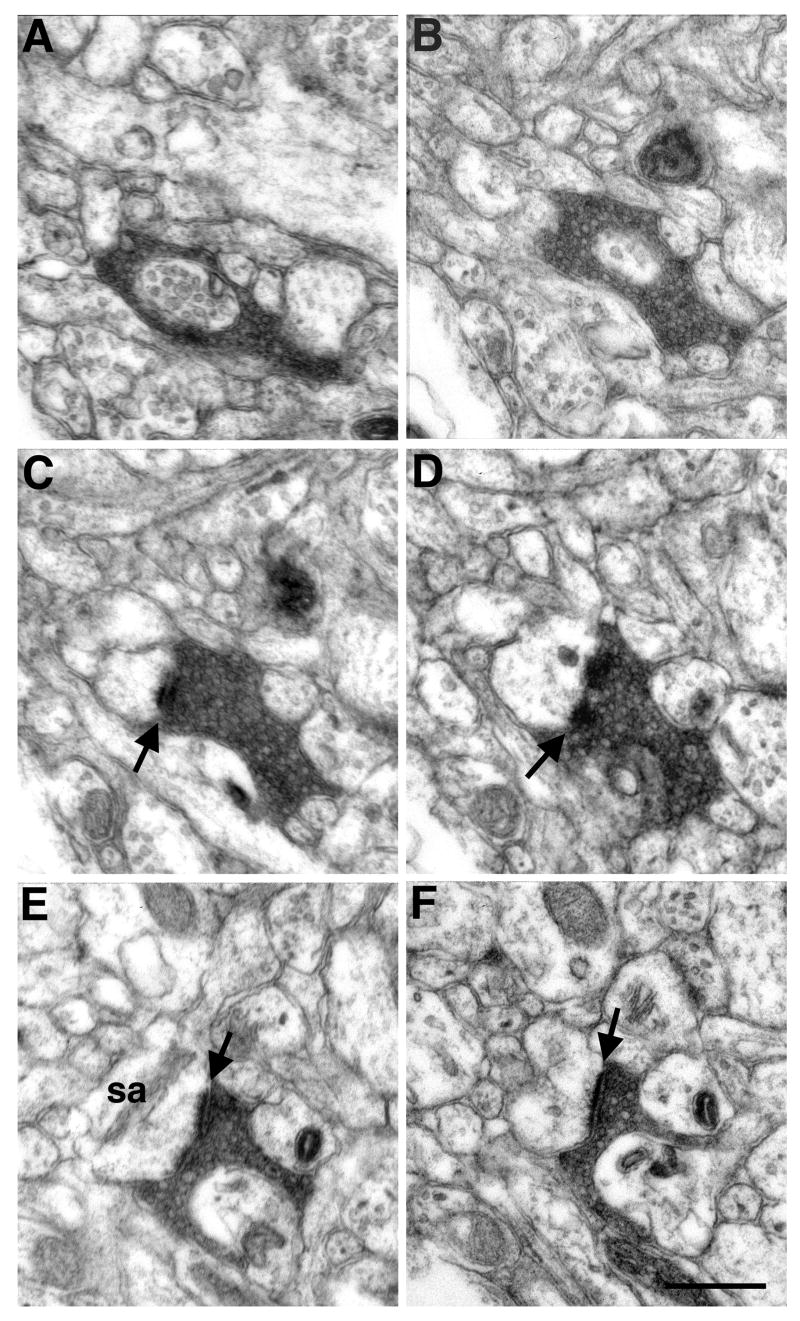

Figure 6.

Electron micrographs of serial sections through a BDA labeled terminal in area TE. Sections are spaced 140 nm apart. This outon was classified as an asymmetric axospinous synapse based on the rounded synaptic vesicles (visible in all sections), the thickened postsynaptic density (arrows; apparent in panels C–F), and the spine apparatus (sa; panel E). Scale bar: 0.5 μm.

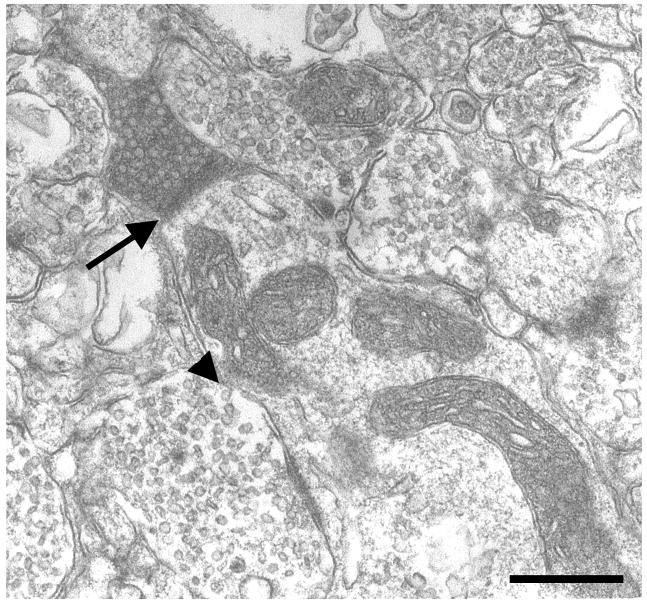

Figure 7.

An electron micrograph of a PHA-L labeled bouton in area TE forming an asymmetric synapse with a dendritic shaft. The postsynaptic density between the amygdaloid bouton and the postsynaptic component is indicated by an arrow. This shaft also receives synapses from 2 axonal terminals of unknown origin (arrowheads). Scale bar: 0.5 μm.

Two amygdaloid boutons in area TE did not form an identifiable synaptic contact. These boutons were ovoid in shape and contained several mitochondria. Both were filled with synaptic vesicles. However, no postsynaptic density could be identified in the serial sections through the boutons.

Area V1

We examined 200 amygdaloid boutons in area V1. These formed 211 synapses, all of which were asymmetric. Eleven of the terminals formed double synapses (Fig. 5). Thirty-nine percent of the postsynaptic densities were perforated, while all others were continuous. Most (189; 89.6%) of the axonal terminals formed synapses with dendritic spines (Fig. 8A–C). Of the 189 spines that received a synapse from an amygdaloid bouton, 17 (9.0%) received a second synapse from an axonal bouton of an unidentified source. A smaller number (22; 10.4%) of the amygdaloid terminals formed synapses onto dendritic shafts (Fig. 8D).

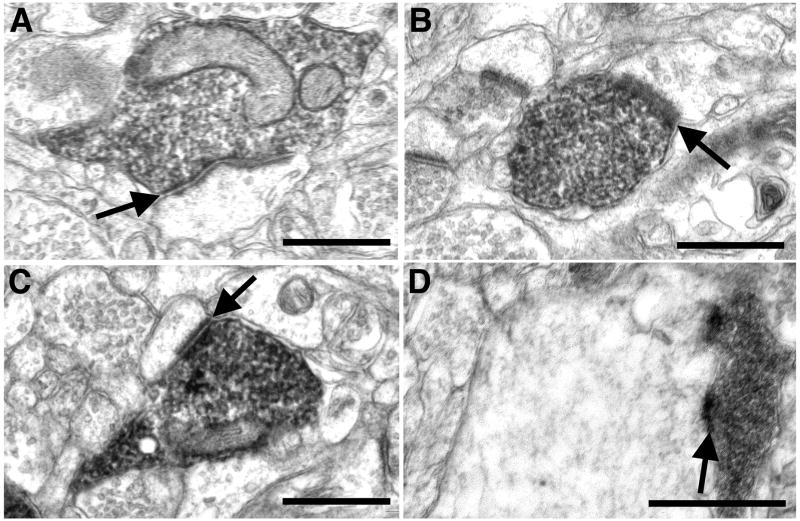

Figure 8.

(A–C) Three different asymmetric synapses between a labeled amygdaloid bouton and a spine in area V1. (D) An asymmetric axodendritic synapse in area V1. Scale bars = 0.5 μm.

DISCUSSION

Synopsis of Findings

Historically, the most widely-recognized amygdaloid connections were with the hypothalamus (Cowan et al., 1965; Ishikawa et al., 1969), and so it was thought that the amygdala was primarily involved in more primitive functions such as modulation of autonomic responses (MacLean, 1970). However, studies in the late 1970’s and throughout the 1980’s demonstrated that the amygdala has widespread efferent and afferent connections with the neocortex (Krettek and Price, 1977; Aggleton et al., 1980; Turner et al., 1980; Van Hoesen, 1981; Amaral and Price, 1984). Substantial attention has been directed at studying the connections of the primate amygdala with regions of the “ventral stream” visual cortex. The amygdala receives projections from higher-level cortices such as areas TE and rostral TEO, but projects to all visual cortical areas including area V1 (Mizuno et al., 1981; Tigges et al., 1982; Tigges et al., 1983; Iwai and Yukie, 1987; Stefanacci and Amaral, 2000; Stefanacci and Amaral, 2002; Amaral et al., 2003; Freese and Amaral, 2005).

This is the first study to examine the ultrastructural characteristics of amygdaloid projections to visual cortices in the macaque monkey. All projections to areas TE and V1 form synapses that are asymmetric. Eighty-four percent of amygdaloid boutons in area TE formed asymmetric axospinous synapses, 15% formed asymmetric axodendritic synapses, and only 1% apparently did not form a synapse. Projections to area V1 were similar: ninety percent of amygdaloid boutons formed asymmetric axospinous synapses and 10% formed asymmetric axodendritic synapses. In both areas, a small percentage (3.5% in area TE and 5.5% in area V1) of amygdaloid boutons formed 2 synapses, usually with spines.

Comparison with Other Studies

Our results are consistent with previous electron microscopic analyses of amygdaloid projections. In the primate, approximately 84% of axonal terminals labeled in the entorhinal cortex following anterogade tracer injections of the basal nucleus form asymmetric synapses onto dendritic spines (Pitkänen et al., 2002). Projections from the rat amygdala to the frontal cortex and from the cat amygdala to the perirhinal and insular cortices also primarily contact dendritic spines (Kita and Kitai, 1990; Smith and Paré, 1994; Paré et al., 1995b; Bacon et al., 1996). Subcortical targets, including the striatum and thalamus, also receive asymmetric axospinous synapses from the basal nucleus (Carlsen and Heimer, 1988; Kita and Kitai, 1990).

We have characterized the amygdalocortical pathways as “feedback” projections (Freese and Amaral, 2005) based on established patterns of corticocortical connectivity (Rockland and Pandya, 1979; Rockland and Virga, 1989; Shipp and Zeki, 1989; Zeki and Shipp, 1989; Felleman and Van Essen, 1991; Salin and Bullier, 1995). Few studies have focused on the ultrastructural characteristics of feedback projections. Johnson and Burkhalter (1996) investigated the ultrastructure of feedback projections from area LM (approximately equivalent to primate area V2) to area V1 in the rat. They found that boutons in this feedback projection almost exclusively (98%) target dendritic spines. In the current study, 84% of the boutons in the projection to area TE contacted dendritic spines and 90% of the boutons in area V1 contacted dendritic spines. Anderson and Martin (1998; 2002) have evaluated the ultrastructure of feedforward systems in the macaque monkey. In projections from area V1 to area MT, 54% of the synapses are with dendritic spines (Anderson et al., 1998) while in the projections from area V2 to area MT, 75% of the synapses are with dendritic spines (Anderson and Martin, 2002). Thus, from available data, there appears to be substantial variability in the percentage of axospinous terminations in different feedback and feedforward systems. Unfortunately, data are far too limited to determine any overarching pattern to the fine structure of these connections.

Functional Implications

Cortico-cortical feedback projections typically terminate in layers I-III and V-VI, but not in layer IV (Felleman and Van Essen, 1991; Salin and Bullier, 1995). Amygdalo-cortical projections to areas TE and V1 fit this anatomically-defined “feedback” pattern. Cortical feedback projections tend to facilitate the responses of neurons (Hupé et al., 1998; Hupé et al., 2001). For example, when area MT is inactivated, neurons in areas V1, V2, and V3 - which all receive feedback projections from area MT - have a decreased firing rate in response to a moving bar stimulus (Hupé et al., 1998). Thus, the feedback projections from area MT tend to enhance responses in areas V1, V2 and V3. We would expect that amygdaloid projections to neurons in the ventral stream visual system would also modulate their responsiveness.

Amygdalo-cortical projections to areas TE and V1 terminate with synapses of the asymmetric variety. Asymmetric synapses, are usually characterized as excitatory while symmetric synapses are usually inhibitory (Shepherd, 1990; Peters et al., 1991). Therefore the amygdalo-cortical synapses examined in this study are most likely excitatory. An electron microscopic study of amygdalo-striatal projections found that they are not GABA-ergic (Carlsen, 1988), lending further support that projections neurons of the basal nucleus use an excitatory neurotransmitter.

While there are no physiological data to confirm the excitatory nature of the amygdalocortial projections in the monkey, there has been work on the amygdaloentorhinal projection in the rat. Electrical stimulation of the rat amygdala evokes negative field potentials in the entorhinal cortex that are indicative of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (Colino and Fernandez de Molina, 1986). Excitatory postsynaptic potentials can be evoked in the entorhinal cortex by amygdala stimulation (Finch et al., 1986). More recently, Paré and colleagues (1995a) found that the amygdala is responsible for sharp wave potentials in the entorhinal cortex of the cat that correlated with an increased probability of neuronal discharges. All of this supports the likelihood that amygdalo-cortical projections are excitatory. However, it would be interesting to directly test this in the monkey brain.

We found that a significant proportion (27% in area TE and 39% in area V1) of amygdaloid asymmetric synapses formed perforated synapses. Perforated synapses were first identified by Peters and Kaiserman-Abramof (1969; 1970) who described them as postsynaptic densities with discontinuities. These discontinuities result in postsynaptic densities that are donut- or horseshoe-shaped. While their exact function is unknown, it has been proposed that perforated postsynaptic densities are more effective than non-perforated postsynaptic densities due to either the closer apposition of pre- and postsynaptic membranes (Sirevaag and Greenough, 1985) or the additional “edges” around the perforations (Peters and Kaiserman-Abramof, 1969; Peters and Kaiserman-Abramof, 1970; Greenough et al., 1978). The closer proximity or edges are hypothesized to be areas of increased synaptic transmission. In support of this hypothesis, the postsynaptic densities of perforated synapses exhibit a significantly higher number of AMPA receptors than those of non-perforated synapses (Desmond and Weinberg, 1998; Ganeshina et al., 2004).

We are not able to address the issue of why some amygdalocortical terminals are perforated and others are not. Perhaps it is a reflection of plasticity in this pathway. An increase in perforated postsynaptic densities, for example, is associated with visual training (Vrensen and Cardozo, 1981) and exposure to complex environments (Greenough et al., 1978; Sirevaag and Greenough, 1985) while a decrease in the number and area of perforated postsynaptic densities correlates with impaired spatial memory in aged rats (Geinisman et al., 1986; Nicholson et al., 2004). These studies suggest that perforated synapses may represent a facilitated synaptic structure that is associated with enhanced behavior.

Functional MRI evidence in humans supports a modulatory action of amygdaloid feedback projections on the activity within visual cortices. There is now substantial evidence that various forms of selective attention can modulate cortical sensory processing. Vuilleumier et al. (2004) examined whether the amygdala might contribute one of these modulatory influences. They used fMRI to examine the activation of visual cortex under two task conditions. The first involved selective attention to faces versus houses. The second involved attention to facial emotion. Subjects included normal controls as well as individuals with either hippocampal or amygdala damage. They found that while activation of the visual cortex could be enhanced in all three subject groups during the selective attention of faces versus houses task, the amygdala-damaged patients did not show enhanced activation during attention to emotional versus neutral faces. The authors conclude that this lack of activation is due to the elimination of the amygdaloid projections to visual cortex. Anderson and Phelps (2001) also demonstrated that patients with bilateral or unilateral lesions of the amygdala have impaired perception of emotionally evocative words. Interestingly, for patients with unilateral damage to the amygdala, only those with damage to the left amygdala demonstrated the perceptual impairment. These human studies serve to emphasize that the amygdaloid projections that we have highlighted in this and the previous paper (Freese and Amaral, 2005) can have substantial functional significance in modulating sensory perception, particularly in situations and with stimuli that are emotionally salient.

Future Studies

This study is a step towards establishing the function of the amygdalo-cortical feedback projections. One missing feature is the identity of the postsynaptic neurons. While it was beyond the scope of this study to characterize the postsynaptic neurons, we can speculate on their identity. Because most of the amygdaloid synapses were formed with dendritic spines, spiny pyramidal neurons are likely to be the primary target of these projections. It would be interesting to know, however, whether interneurons are also in receipt of amygdaloid inputs. Previous electron microscopic studies have revealed that the diameter of dendrites of GABAergic interneurons vary widely, their shafts have many mitochondria, they have a more electron-dense cytoplasm, and typically form multiple synapses (Somogyi et al., 1983; Kisvarday et al., 1985; Anderson and Martin, 2002). Based on these ultrastructural criteria, we believe that some of the axodendritic synapses we observed may be on GABAergic neurons. However, this would need to be confirmed with a double labeling study. Even without this important information, it is already clear that the synaptic economy of the visual cortex can be significantly influenced through the activity of the amygaloid complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Dr. Pierre Lavenex, Pamela Tennant and Jeff Bennett for surgical and immunohistochemical assistance, to K.C. Brown for technical assistance with immunohistochemistry and digitizing negatives, and to Drs. H. Jürgen Wenzel, Xia-bo Liu, and E. Chris Muly for sharing their expertise in electron microscopic techniques.

Grant support: NIH grants MH41479 (D.G.A.) and MH12876 (J.L.F.). These studies were conducted, in part, at the California National Primate Research Center (RR00169).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AB

accessory basal nucleus

- amts

anterior middle temporal sulcus

- BDA

biotinylated dextran amine

- Bi

basal nucleus, intermediate division

- Bmc

basal nucleus, magnocellular division

- Bpc

basal nucleus, parvicellular division

- ccs

calcarine sulcus

- DAB

3′3′-Diaminobenzidine

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- EC

entorhinal cortex

- ecs

ectocalcarine sulcus

- ios

inferior occipital sulcus

- KPBS

potassium phosphate buffered saline

- L

lateral nucleus

- ls

lunate sulcus

- NGS

normal goat serum

- PHA-L

Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin

- PL

Paralaminar nucleus

- rs

rhinal sulcus

- sts

superior temporal sulcus

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- TOACP

temporal-occipital amygdalo-cortical pathway

References

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio A. Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature. 1994;372(6507):669–672. doi: 10.1038/372669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Fear and the human amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1995 September 1995;15:5879–5891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP. The amygdala : a functional analysis. xiv. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 690. [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Burton MJ, Passingham RE. Cortical and subcortical afferents to the amygdala of the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Brain Res. 1980;190(2):347–368. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Behniea H, Kelly JL. Topographic organization of projections from the amygdala to the visual cortex in the macaque monkey. Neuroscience. 2003;118(4):1099–1120. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)01001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Price JL. Amygdalo-cortical projections in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1984;230:465–496. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Price JL, Pitkänen A, Carmichael T. Anatomical organization of the primate amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton J, editor. The Amygdala: Neurobiological Aspects of Emotion, Memory, and Mental Dysfunction. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1992. pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AK, Phelps EA. Lesions of the human amygdala impair enhanced perception of emotionally salient events. Nature. 2001;411(6835):305–309. doi: 10.1038/35077083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Binzegger T, Martin KA, Rockland KS. The connection from cortical area V1 to V5: a light and electron microscopic study. J Neurosci. 1998;18(24):10525–10540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10525.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Martin KA. Connection from cortical area V2 to MT in macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443(1):56–70. doi: 10.1002/cne.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armony JaL JE. How danger is encoded: towards a systems, cellular, and computational understanding of cognitive-emotional interactions in fear circuits. In: Gazzaniga M, editor. The Cognitive Neurosciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 1067–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon SJ, Headlam AJ, Gabbott PL, Smith AD. Amygdala input to medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in the rat: a light and electron microscope study. Brain Research. 1996;720(1–2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman MD, Lavenex P, Mason WA, Capitanio JP, Amaral DG. The development of mother-infant interactions after neonatal amygdala lesions in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2004;24(3):711–721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3263-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen J. Immunocytochemical localization of glutamate decarboxylase in the rat basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, with special reference to GABAergic innervation of amygdalostriatal projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273(4):513–526. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen J, Heimer L. The basolateral amygdaloid complex as a cortical-like structure. Brain Res. 1988;441(1–2):377–380. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colino A, Fernandez de Molina A. Electrical activity generated in subicular and entorhinal cortices after electrical stimulation of the lateral and basolateral amygdala of the rat. Neuroscience. 1986;19(2):573–580. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan WM, Raisman G, Powell TPS. The connexions of the amygdala. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1965;28:137–151. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.28.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Whalen PJ. The amygdala: vigilance and emotion. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6(1):13–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond NL, Weinberg RJ. Enhanced expression of AMPA receptor protein at perforated axospinous synapses. Neuroreport. 1998;9(5):857–860. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199803300-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery NJ, Capitanio JP, Mason WA, Machado CJ, Mendoza SP, Amaral DG. The effects of bilateral lesions of the amygdala on dyadic social interactions in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Behav Neurosci. 2001;115(3):515–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1(1):1–47. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.1-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch DM, Wong EE, Derian EL, Chen XH, Nowlin-Finch NL, Brothers LA. Neurophysiology of limbic system pathways in the rat: projections from the amygdala to the entorhinal cortex. Brain Res. 1986;370(2):273–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freese JL, Amaral DG. The organization of projections from the amygdala to visual cortical areas TE and V1 in the Macaque monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005 doi: 10.1002/cne.20945. press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganeshina O, Berry RW, Petralia RS, Nicholson DA, Geinisman Y. Differences in the expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors between axospinous perforated and nonperforated synapses are related to the configuration and size of postsynaptic densities. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468(1):86–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.10950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman Y, de Toledo-Morrell L, Morrell F. Aged rats need a preserved complement of perforated axospinous synapses per hippocampal neuron to maintain good spatial memory. Brain Res. 1986;398(2):266–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EG. Axo-somatic and axo-dendritic synapses of the cerebral cortex: an electron microscope study. J Anat. 1959;93:420–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough WT, West RW, DeVoogd TJ. Subsynaptic plate perforations: changes with age and experience in the rat. Science. 1978;202(4372):1096–1098. doi: 10.1126/science.715459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microsc. 1987;147(Pt 3):229–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupé JM, James AC, Girard P, Bullier J. Response Modulations by Static Texture Surround in Area V1 of the Macaque Monkey Do Not Depend on Feedback Connections From V2. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85(1):146–163. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupé JM, James AC, Payne BR, Lomber SG, Girard P, Bullier J. Cortical feedback improves discrimination between figure and background by V1, V2 and V3 neurons. Nature. 1998;394(6695):784–787. doi: 10.1038/29537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa I, Kawamura S, Tanaka O. An experimental study on the efferent connections of the amygdaloid complex in the cat. Acta Medica Okayama. 1969;23:519–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai E, Yukie M. Amygdalofugal and amygdalopetal connections with modality-specific visual cortical areas in macaques (Macaca fuscata, M. mulatta, and M. fascicularis) J Comp Neurol. 1987;261(3):362–387. doi: 10.1002/cne.902610304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RR, Burkhalter A. Microcircuitry of forward and feedback connections within rat visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1996;368(3):383–398. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960506)368:3<383::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisvarday ZF, Martin KA, Whitteridge D, Somogyi P. Synaptic connections of intracellularly filled clutch cells: a type of small basket cell in the visual cortex of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;241(2):111–137. doi: 10.1002/cne.902410202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H, Kitai ST. Amygdaloid projections to the frontal cortex and the striatum in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;298(1):40–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.902980104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettek JE, Price JL. Projections from the amygdaloid complex to the cerebral cortex and thalamus in the rat and cat. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172(4):687–722. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE, Cicchetti P, Xagoraris A, Romanski LM. The lateral amygdaloid nucleus: sensory interface of the amygdala in fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 1990;10(4):1062–1069. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01062.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichnetz GR, Povlishick JT, Astruc J. A prefronto-amgdayloid projection in the monkey: light and electron microscopic evidence. Neuroscience Letters. 1976;2:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(76)90157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVay S. Synaptic organization of claustral and geniculate afferents to the visual cortex of the cat. J Neurosci. 1986;6(12):3564–3575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-12-03564.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean PD. The Triune Brain, Emotion, and Scientific Bias. In: Schmitt FO, editor. Neurosciences: Second Study Program. New York: Rockefeller University Press; 1970. pp. 336–349. [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Capitanio JP, Machado CJ, Mendoza SP, Amaral DG. Amygdalectomy and responsiveness to novelty in rhesus monkeys: Generality and individual consistency of effects. Emotion accepted. 2005 doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek GA. Practical Electron Microsopy for Biologists. New York: Wiley; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno N, Uchida K, Nomura S, Nakamura Y, Sugimoto T, Uemura-Sumi M. Extrageniculate projections to the visual cortex in the macaque monkey: an HRP study. Brain Res. 1981;212(2):454–459. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90477-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Conscious and unconscious emotional learning in the human amygdala [see comments] Nature. 1998;393(6684):467–470. doi: 10.1038/30976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson DA, Yoshida R, Berry RW, Gallagher M, Geinisman Y. Reduction in size of perforated postsynaptic densities in hippocampal axospinous synapses and age-related spatial learning impairments. J Neurosci. 2004;24(35):7648–7653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1725-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré D, Dong J, Gaudreau H. Amygdalo-entorhinal relations and their reflection in the hippocampal formation: generation of sharp sleep potentials. J Neurosci. 1995a;15(3 Pt 2):2482–2503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02482.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré D, Smith Y, Paré JF. Intra-amygdaloid projections of the basolateral and basomedial nuclei in the cat: Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin anterograde tracing at the light and electron microscopic level. Neuroscience. 1995b;69(2):567–583. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00272-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease DC. Histological Techniques for Electron Microscopy. New York: Academic Press; 1964. p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Kaiserman-Abramof IR. The small pyramidal neuron of the rat cerebral cortex. The synapses upon dendritic spines. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1969;100(4):487–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00344370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Kaiserman-Abramof IR. The small pyramidal neuron of the rat cerebral cortex. The perikaryon, dendrites and spines. Am J Anat. 1970;127(4):321–355. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001270402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster Hd. The fine structure of the nervous system : neurons and their supporting cells. xviii. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. p. 494. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Kelly JL, Amaral DG. Projections from the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei of the amygdala to the entorhinal cortex in the macaque monkey. Hippocampus. 2002;12(2):186–205. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather MD, Lavenex P, Mauldin-Jourdain ML, Mason WA, Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Amaral DG. Increased social fear and decreased fear of objects in monkeys with neonatal amygdala lesions. Neuroscience. 2001;106(4):653–658. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Veenman CL, Medina L, Jiao Y, Del Mar N, Honig MG. Pathway tracing using biotinylated dextran amines. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;103(1):23–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockland KS, Pandya DN. Laminar origins and terminations of cortical connections of the occipital lobe in the rhesus monkey. Brain Res. 1979;179(1):3–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockland KS, Virga A. Terminal arbors of individual “feedback” axons projecting from area V2 to V1 in the macaque monkey: a study using immunohistochemistry of anterogradely transported Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285(1):54–72. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin PA, Bullier J. Corticocortical connections in the visual system: structure and function. Physiol Rev. 1995;75(1):107–154. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savander V, Miettinen R, Ledoux JE, Pitkanen A. Lateral nucleus of the rat amygdala is reciprocally connected with basal and accessory basal nuclei: a light and electron microscopic study. Neuroscience. 1997;77(3):767–781. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd GM. The Synaptic Organization of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shipp S, Zeki S. The Organization of Connections between Areas V5 and V2 in Macaque Monkey Visual Cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1(4):333–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidibe M, Bevan MD, Bolam JP, Smith Y. Efferent connections of the internal globus pallidus in the squirrel monkey: I. Topography and synaptic organization of the pallidothalamic projection. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382(3):323–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirevaag AM, Greenough WT. Differential rearing effects on rat visual cortex synapses. II. Synaptic morphometry. Brain Res. 1985;351(2):215–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Paré D. Intra-amygdaloid projections of the lateral nucleus in the cat: PHA-L anterograde labeling combined with postembedding GABA and glutamate immunocytochemistry. The journal of comparitive neurology. 1994;342:232–248. doi: 10.1002/cne.903420207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Paré JF, Paré D. Differential innervation of parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons of the basolateral amygdaloid complex by cortical and intrinsic inputs. J Comp Neurol. 2000;416(4):496–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Kisvarday ZF, Martin KA, Whitteridge D. Synaptic connections of morphologically identified and physiologically characterized large basket cells in the striate cortex of cat. Neuroscience. 1983;10(2):261–294. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanacci L, Amaral DG. Topographic organization of cortical inputs to the lateral nucleus of the macaque monkey amygdala: a retrograde tracing study. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421(1):52–79. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000522)421:1<52::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanacci L, Amaral DG. Some observations on cortical inputs to the macaque monkey amygdala: an anterograde tracing study. J Comp Neurol. 2002;451(4):301–323. doi: 10.1002/cne.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanacci L, Farb CR, Pitkänen A, Go G, LeDoux JE, Amaral DG. Projections from the lateral nucleus to the basal nucleus of the amygdala: a light and electron microscopic PHA-L study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323(4):586–601. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigges J, Tigges M, Cross NA, McBride RL, Letbetter WD, Anschel S. Subcortical structures projecting to visual cortical areas in squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1982;209(1):29–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.902090104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigges J, Walker LC, Tigges M. Subcortical projections to the occipital and parietal lobes of the chimpanzee brain. J Comp Neurol. 1983;220(1):106–115. doi: 10.1002/cne.902200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BH, Mishkin M, Knapp M. Organization of the amygdalopetal projections from modality-specific cortical association areas in the monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1980;191:515–543. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerleider La MM. In: Two cortical visual systems. Ingle D, Goodale MA, Mansfield GJQ, editors. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1982. pp. 549–586. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoesen GW. The Differential Distribution, Diversity and Sprouting of Cortical Projections to the Amygdala in the Rhesus Monkey. In: Ben-Ari Y, editor. The Amygdaloid Complex. Amsterdam: Elseview/North Holland Press; 1981. pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vrensen G, Cardozo JN. Changes in size and shape of synaptic connections after visual training: an ultrastructural approach of synaptic plasticity. Brain Res. 1981;218(1–2):79–97. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90990-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Armony JL, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Effects of attention and emotion on face processing in the human brain: an event-related fMRI study. Neuron. 2001;30(3):829–841. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Richardson MP, Armony JL, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Distant influences of amygdala lesion on visual cortical activation during emotional face processing. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(11):1271–1278. doi: 10.1038/nn1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296(1):1–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki S, Shipp S. Modular Connections between Areas V2 and V4 of Macaque Monkey Visual Cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1(5):494–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.