Abstract

Background

Vertebrate classic cadherins are divided into type I and type II subtypes, which are individually expressed in brain subdivisions (e.g., prosomeres, rhombomeres, and progenitor domains) and in specific neuronal circuits in region-specific manners. We reported previously the expression of cadherin19 (cad19) in Schwann cell precursors. Cad19 is a type II classic cadherin closely clustered on a chromosome with cad7 and cad20. The expression patterns of cad7 and cad20 have been reported previously in chick embryo but not in the developing and adult central nervous system of mammals. In this study, we identified rat cad7 and cad20 and analyzed their expression patterns in embryonic and adult rat brains.

Results

Rat cad7 protein showed 92% similarity to chick cad7, while rat cad20 protein had 76% similarity to Xenopus F-cadherin. Rat cad7 mRNA was initially expressed in the anterior neural plate including presumptive forebrain and midbrain regions, and then accumulated in cells of the dorsal neural tube and in rhombomere boundary cells of the hindbrain. Expression of rat cad20 mRNA was specifically localized in the anterior neural region and rhombomere 2 in the early neural plate, and later in longitudinally defined ventral cells of the hindbrain. The expression boundaries of cad7 and cad20 corresponded to those of region-specific transcription factors such as Six3, Irx3 and Otx2 in the neural plate, and Dbx2 and Gsh1 in the hindbrain. At later stages, the expression of cad7 and cad20 disappeared from neuroepithelial cells in the hindbrain, and was almost restricted to postmitotic cells, e.g. somatic motor neurons and precerebellar neurons. These results emphasized the diversity of cad7 and cad20 expression patterns in different vertebrate species, i.e. birds and rodents.

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings suggest that the expression of cad7 and cad20 demarcates the compartments, boundaries, progenitor domains, specific nuclei and specific neural circuits during mammalian brain development.

Background

In the early neural plate, the brain primodium is subdivided into several domains, i.e., neuromeres, to generate regional differences and units [1]. The hindbrain primordium is morphologically divided into lineage-restricted functional metameric units called rhombomeres [2]. Neuroepithelial cells are initially scattered in the hindbrain neuroepithelium, but are sorted gradually into each compartment [3]. In the forebrain, that consists of the diencephalon and telencephalon, the primordium is longitudinally divided into prosomeres, which are defined by the expression border of various transcription factors such as homeodomain (HD) proteins [4,5], and a lineage restriction of neuroepithelial cells between each subdivision has been reported in the caudal diencephalon of the chick embryo [6]. In each region of the hindbrain and spinal cord, the neuroepithelium is also regionalized into basal and alar plates, which are separated at a groove called the sulcus limitans. Several molecular makers, e.g., HD transcription factors, subdivide the neuroepithelium into several discrete progenitor domains that give rise to different types of neurons along the dorsoventral (D-V) axis [7].

Previous studies demonstrated the expression of cadherin superfamily genes encoding cell adhesion molecules in the brain and the spinal cord, with distinct expression patterns that correspond with the subdivisions of the brain and the spinal cord [8-12]. These studies proposed that cadherin-mediated differential cell affinity establishes various compartments and regionalizes the neuroepithelium. Vertebrate cadherin superfamily genes are categorized into subfamilies, such as classic cadherins, protocadherins, and desmosomal cadherins [13]. Classic cadherins have cadherin-repeats in an extracellular region called EC (extracellular cadherin) domain and associate with β-catenin and p120-catein in the cytoplasmic domains that connect to the actin cytoskeleton [13]. The EC1 domain of classic cadherin shows adhesive properties that enhance the homophilic binding of cadherin. Classic cadherins are categorized into type I and type II groups with or without conserved amino acids, His-Ala-Val (HAV) within EC1 domain [14]. The adhesive affinities of type I cadherins have been studied extensively. Cells expressing single type I cadherin, such as E-cadherin or N-cadherin, prefer to adhere to those expressing the same cadherin via homophilic interaction rather than heterophilic binding. For example, the neuroectoderm is segregated from the ectoderm by distinct affinity of N-cadherin and E-cadherin during the formation of the neural tube [15]. In contrast, R-cadherin and N-cadherin, which are type I cadherins, interact in a heterophilic manner [16], and the adhesive interaction between individual subtypes of type II cadherin is not always homophilic in nature [17]. Therefore, the complexity of homophilic and/or heterophilic interactions between each type II cadherin subtype may be involved in several developmental processes beyond tissue segregation during early embryogenesis.

F-cadherin (F-cad), a member of type II classic cadherins, is expressed in the area adjacent to the sulcus limitans, the boundary between the basal and alar plates, which restricts positioning of neuroepithelial cells in Xenopus embryos [18,19]. In the chick neural tube, cadherin7 (cad7) is expressed not only in migratory neural crest cells but also in the domain ventral to the sulcus limitans of the neural tube [20-22]. R-cadherin (R-cad) and cadherin6 (cad6) are expressed in the primodia of the mouse cerebral cortex and striatum, respectively, and their differential cell affinities mediate segregation at the corticostriatal boundary [23]. Other subtypes of classic cadherins also have multiple functions in the developing and adult brain, such as involvement in neuronal migration and connectivity of specific neuronal circuits, and synaptic formation in the brain. For example, cad6, cad8 and cad11 are observed in specific neural circuits [24,25], and α N-catenin and N-cadherin, which are localized in the pre- and postsynaptic regions, modulate dendritic spine formation in an activity-dependent manner [26]. So far, more than 20 members of type II classic cadherin have been identified. In Schwann cell precursors, we reported previously the expression of rat cad19 gene [27], which is a type II subtype clustered with cad7 and cad20 on chromosome 13. In mice, cad7 is expressed only in adult tissues [28], whereas cad20, a F-cad homologue, is expressed in early neural tissues [28,29]. However, little is known about the expression patterns of cad7 and cad20 in the developing and adult rodent brains. In this study, we focused on cad7 and cad20 genes and analyzed their expression patterns in the developing and adult rat brains. The results showed that the expression borders of cad7 and cad20 corresponded with those of regional compartments and boundaries, which were marked with the expression of region-specific transcription factors. Cad7 and cad20 were also expressed in neurons of several nuclei that form the cerebellar/precerebellar circuitry in the late embryonic and adult hindbrain. The results suggest the contribution of cad7 and cad20 in the formation of compartment/boundary and specific neuronal circuitry in the rat hindbrain.

Results

Isolation of rat cad7 and cad20

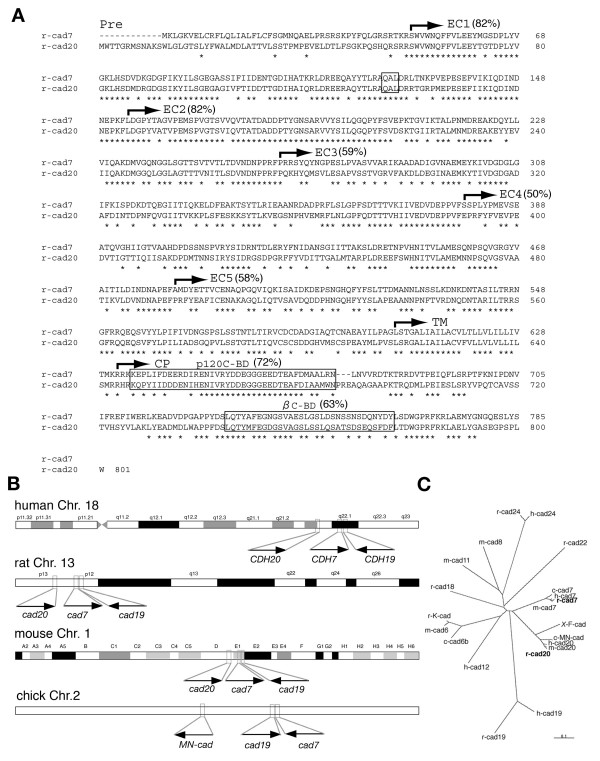

To examine the expression of rodent homologues of chick cad7 and Xenopus F-cad, we searched for rat genome sequences orthologous to chick cad7 and Xenopus F-cad. We found highly conserved sequences on rat chromosome 13p12 and cloned cDNAs covering open reading frames (ORFs) of putative rat cad7 and cad20 proteins by RT-PCR (Fig. 1A, B, Table 1). Classic cadherins consist of EC domains (or cadherin repeats), a transmembrane domain, and cytoplasmic domains. The putative ORF of rat cad7 encoded 785 amino acids and the protein showed 92% similarity with chick cad7 [20], and 96% similarity with human cad7 [17,30] (Fig. 1A). The putative ORF of rat F-cad encoded 801 amino acids, and the protein had 76% similarity with Xenopus F-cad [18] (Fig. 1A), 86% similarity with chick MN-cadherin (MN-cad) [31,32] and 95% similarity with human CDH20, a homologue of F-cad [30] (Fig. 1A). β-catenin and p120 catenin binding sites were conserved within the cytoplasmic domains of rat cad7 and cad20 proteins, which showed 72% and 63% identities, respectively (Fig. 1A). The EC1 and EC2 domains of cad7 and cad20 proteins were highly conserved with 82% identities (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that our two-cloned type II classic cadherins are homologues of chick cad7 and Xenopus F-cad.

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequences and chromosome mapping of rat cad7 and cad20. A: Alignments of rat cad7 and cad20 protein sequences. Asterisks indicate identical amino acids between cad7 and cad20 proteins. Numbers indicate percentage of identical amino acids in each domain and catenin binding domains. B: The positions of cad7, cad19 and cad20 on the human, rat, mouse and chick genomes, based on genome data search. Directions of arrows indicate coding on forward (right) and reverse (left) strands, respectively. C: Phylogenetic tree for type II classic cadherins. m, mouse; r, rat; h, human; c, chick; X, Xenopus.

Table 1.

Characterization of cad20/cad19/cad7 gene cluster in different species.

| Species | Gene | Chromosome | Ensemble Gene model | References |

| Chick | MN-cad | 2 (2_19.90) | 68,341,649–68,376,741(-) | [31] Price et al., 2002, [32] Shirabe et al., 2005 |

| cad19 | 2 (2_19.90) | 95,067,813–95,101,300(+) | [27] Takahashi and Osumi, 2005, [33] Luo et al., 2007 | |

| cad7 | 2 (2_19.90) | 95,357,588–95,418,911(-) | [20,21] Nakagawa and Takeichi, 1995, 1998 | |

| Rat | cad20 | 13 (13p12) | 10,970,187–11,038,903(+) | In this study |

| cad7 | 13 (13p12) | 16,884,417–17,020,843(+) | In this study | |

| cad19 | 13 (13p12) | 18,148,715–18,230,353(-) | [27] Takahashi and Osumi, 2005 | |

| Mouse | cad20 | 1 | 104,833,281–104,893,569 (+) | [28] Moore et al., 2004, [29] Faulkner-Jones et al., 1999 |

| cad7 | 1 | 109,880,766–110,037,943(+) | [28] Moore et al., 2004 | |

| cad19 | 1 | 110,788,240–110,854,295(-) | [27] Takahashi and Osumi, 2005 | |

| Human | CDH20 | 18 (18q22-q23) | 57,308,755–57,373,345(+) | [30] Kools et al., 2000 |

| CDH7 | 18 (18q22-q23) | 61,568,468–61,699,155(+) | [17] Shimoyama et al., 2000, [30] Kools et al., 2000 | |

| CDH19 | 18 (18q22-q23) | 62,322,301–62,422,196(-) | [30] Kools et al., 2000 |

Human CDH7, CDH19 and CDH20 genes are clustered on chromosome18q22-p23 [30]. Accordingly, we examined whether similar gene clusters are conserved in the rat, mouse and chick genomes. Cad7 and cad20 genes were closely localized in the same chromosome with cad19 (Fig. 1B). It is noteworthy that in the chick genome, the position of cad7, MN-cad and cad19 [33] gene cluster on chromosome 2 is different from that of cad7 and cad20 on human, rat, and mouse genomes (Fig. 1C, Table 1).

Region-specific expression of cad7 in the developing rat embryo

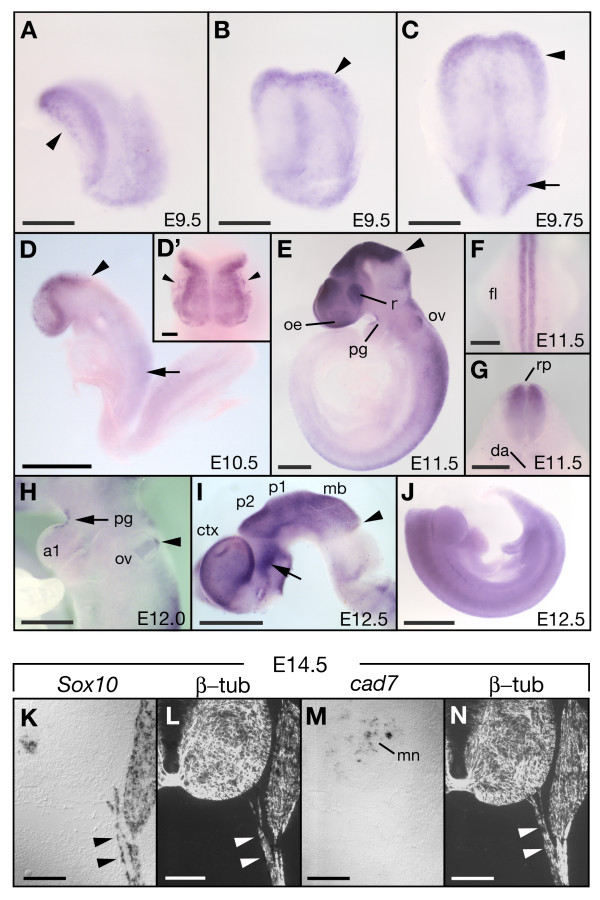

We first examined the expression patterns of cad7 in the rat embryos by whole mount in situ hybridization. Expression of cad7 mRNA appeared at the edge of the anterior neural plate at embryonic day (E) 9.5–9.75 and in the lateral plate at the posterior region (Fig. 2A–C). At E10.5 (12 somites stage), rostral expression of cad7 was exclusive to the presumptive forebrain, midbrain and caudal neural tube, and then was strongly identified at the edge of the neural plate, which corresponds to neural crest cells (Fig. 2D, D'). Cad7 was expressed in migrating neural crest-derived cells in the cephalic region (Fig. 2D'), but disappeared at later stages. At E11.5, cad7 was expressed in the rostral brain regions including the telencephalon, diencephalon and midbrain, and the sharp posterior border of the expression apparently corresponded to the midbrain/hindbrain boundary (MHB) (Fig. 2E). In the caudal hindbrain and the spinal cord, cad7 was expressed in the dorsal neuroepithelium but no expression was noted in the roof plate (Fig. 2F, G). Cad7 expression also appeared in the olfactory epithelium, retina, dorsal area of the otic vesicle and the pharyngeal groove at E11.5 (Fig. 2E). At E12.0, the pattern of cad7 expression was similar to that at E11.5 (Fig. 2H). At E12.5, cad7 expression extended to the cerebral cortex, the diencephalon including the presumptive pretectum (p1), thalamus (p2) and prethalamus (p3), and the dorsal midbrain (Fig. 2I). Immunostaining of the chick diencephalon with antibody against cad7 showed that cad7 expression demarcated the pretectum, ventral thalamus and the zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI) but not the dorsal thalamus [34], suggesting that the cad7-expressing diencephalic region is not conserved in ZLI and dorsal thalamus in the rat and chick. Previous studies demonstrated the expression of cad7 in chick neural crest-derived cells including Schwann cells and their precursors [20,21]. In E12.5 rat embryo, cad7 mRNA was undetectable in the dorsal root ganglia and neural crest-derived migrating cells at the trunk level (Fig. 2J). We further examined cad7 expression in Schwann cell precursors at E14.5 [27]. We performed in situ hybridization on serial sections for cad7 and Sox10, a maker of neural crest-derived cells [35], and immunostaining of the same sections with β-tubulin antibody (Tuj1) to detect the nerve of motor neurons (Fig. 2K–N). In contrast to the expression of Sox10 in Schwann cell precursors on the motor nerve, cad7 was not expressed in these cells (Fig. 2K and 2M). These results suggest that rat cad7 gene is activated in the central but not peripheral nervous system during neural development.

Figure 2.

Expression patterns of cad7 in the developing rat embryo. A-C: The expression of cad7 mRNA in the anterior margin of the early neural plate at E9.5–9.75 (arrowhead in A, B and C), and in the lateral plate at E9.75 (arrow in C). These pictures show lateral (A), ventral (B) and dorsal (C) views. D: Lateral view showing the expression of cad7 in the brain region anterior to the midbrain/hindbrain boundary (arrowhead) and caudal neural tube (arrow) at E10.5. D': Dorsal view of D. The expression of cad7 is detected at the edge of the neural plate and part of migrating neural crest cells (arrowheads). E-G: Expression of cad7 in the forebrain and midbrain (E). Cad7 is expressed in the dorsal region of the otic vesicle (ov), and in the olfactory epithelium (oe) and retina (r) at E11.5 (E). G is a cross-section at the fore limb (fl) level. In the hindbrain and spinal cord, cad7 is expressed in the dorsal neuroepithelium and the expression is absent in the roof plate (rp) (F, G). E and F images indicate lateral and ventral view, respectively. H: Lateral view of cad7 expression in the pharyngeal region at E12.0. Arrow and arrowhead indicate expression of cad7 in the pharyngeal groove (pg) and otic vesicle (ov), respectively. I-J: Lateral view of cad7 staining in the brain of E12.5 embryos. Arrow in I indicates the expression of cad7 in the ventral domains of prosomere3 (p3) and secondary prosencephalon. No expression of cad7 in the dorsal root ganglion cells at the trunk level (J). K-N: On cross-sections from E14.5 embryo, cad7 transcripts are detected in the subpopulation of motor neurons (mn) but not in the dorsal root ganglion or Schwann cell precursors (arrowheads in K, and M) expressing Sox10, along motor nerve (arrowheads in L and N). al, pharyngeal arch 1; da, dorsal aorta; ctx, cerebral cortex; mb, midbrain. Scale bars: 200 μm in A-C, G and K-N; 400 μm in D; 100 μm in D'; 500 μm in E and H; 300 μm in F; 1 mm in I and J.

Expression borders of cad7 and cad20 are adjacent to those of transcription factors in the early neural plate

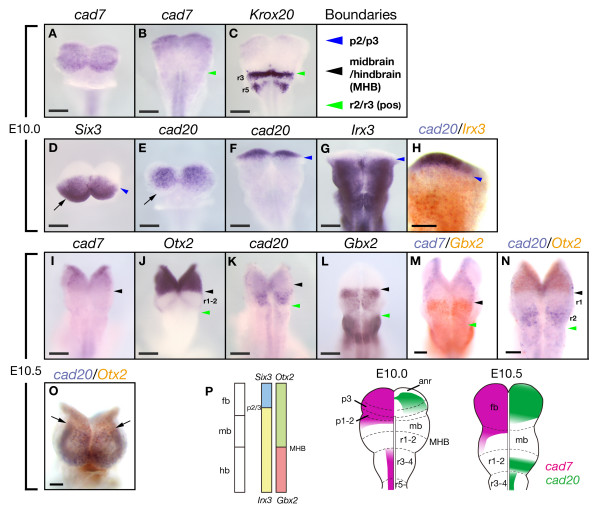

Since previous reports suggested cadherins expression in specific regions corresponding to prosomere and rhombomere compartments [36,37], we next examined the expression borders of cad7, cad20 and compared their expressions with those of transcription factors showing region-specific expression patterns at early development stages. At E10.0 (6-somites stage), cad7 expression became restricted to the anterior region including the forebrain and caudal hindbrain (Fig. 3A). The anterior border of cad7 in the hindbrain corresponded to that of Krox20 (Fig. 3B, C), a zinc-finger transcription factor, at rhombomere 3 (r3) [38]. The expression of cad20 was more restricted in the anterior region and overlapped with the expression of Six3 [39], a HD protein (Fig. 3D, E). A previous report showed that the prospective position of the zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI) is demarcated by the expression boundaries of Six3 and Irx3, HD transcription factors, in the chick embryo [40]. Since the posterior border of cad20 expression was adjacent to the anterior border of Irx3 (Fig. 3F–H), cad20 expression indicates the prospective position of ZLI in the rat neural plate.

Figure 3.

Expression of cad7 and cad20 and transcription factors in the early neural plate. Images shown in A, D, E, O and B, C, F-N are taken from the anterior and dorsal sides, respectively. A-I: Cad7 mRNA is expressed in the forebrain region (A). The anterior border of cad7 expression in the hindbrain is consistent with that of Krox20 in the r3 (green arrowhead in B and C). At E10.5, cad20 is expressed in the forebrain region and the expression region overlaps with that of Six3 (D, E). Cad20 expression is absent in the anterior margin of the neural plate (arrow in E), which is different from Six3 expression (arrow in D). Blue arrowheads in D and G indicate the expression boundary between Six3 and Irx3. The boundary between cad20- and Irx3-domains demarcates the position of the presumptive zona limitans intrathalamica (ZLI) (arrowhead in F, G and H). I-O: At E10.5, the posterior border of cad7 expression corresponds to the midbrain/hindbrain boundary (MHB) as indicated by Gbx2 (black arrowhead in M). The border of cad20 expression is not consistent with the posterior border of Otx2 (black arrowhead in N), the expression is detected in the r2 region expressing Gbx2. The posterior border of cad20 is detected anterior to forebrain/midbrain boundary (arrows in O). P: Schematic illustrations of mapping of cad7 and cad20 in the early stages. pos, pre otic sulcus; fb, forebrain; mb, midbrain; hb, hindbrain, anr, anterior neural ridge; MHB, midbrain/hindbrain boundary. Scale bars: 200 μm in A-H; 400 μm in I-L; 200 μm in M-O.

Next, we compared the expression domains of cad7 and cad20 with those of transcription factors at E10.5 stage (10–12 somite stage). Otx2 and Gbx2 are HD transcription factors that establish the MHB with mutual repression [41]. Remarkably, the posterior border of cad7 expression corresponded with the MHB (Fig. 3I, M). The second domain of cad20 was identified in the hindbrain in r2 region at areas positive for Gbx2 (Fig. 3K, L and 3N) whilst the expression of Otx2 was excluded (Fig. 3J, N). At E10.5, the posterior border of cad20 in the forebrain became sharper (Fig. 3O). These results indicate that the expression borders of cad7 and cad20 correspond to the prosomere and rhombomere boundaries in the early neural plate.

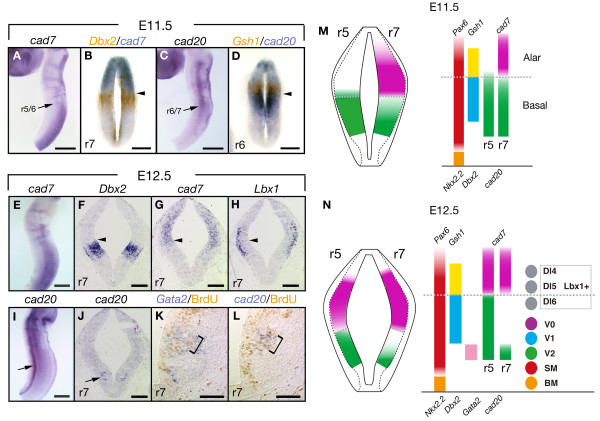

Cad7 and cad20-expressing domains correspond to progenitor domain boundary along the D-V axis

The hindbrain and spinal cord are subdivided into the basal plate and alar plate, which give rise to both motor/interneurons and interneurons, respectively. The boundary between these plates (known as the sulcus limitans) is visualized as a groove at the apical surface of the neural tube [42]. Previous reports suggested that the dorsal borders of Xenopus F-cad and chick cad7 correspond with the position of the sulcus limitans as defined by HD transcription factors [18,19,22], suggesting that the basal/alar boundary can be detected by differential expression of type II cadherin subtypes as molecular makers. Therefore, we investigated whether rat cad7 and cad20 mark the alar/basal boundary and discrete progenitor domains in the developing hindbrain. At E11.5 prior to differentiation of interneurons [43], cad7 mRNA was expressed in dorsal progenitor cells at r6-7 in the hindbrain (Fig. 4A), and cad20 was longitudinally expressed in the midline of the hindbrain neuroepithelium at r1-6 (Fig. 4C). To examine the correlation between the expression domain and progenitor domains, which are subdivided by the different expression patterns of HD proteins [7,43], we performed in situ hybridization using probes for Gsh1 and Dbx2 [44,45]. Double staining for cad7 and Dbx2 in E11.5 embryos indicated that the ventral border of cad7 was adjacent to the dorsal border of Dbx2-domain (Fig. 4B). Although cad20 was somewhat expressed in the domain ventral to Gsh1-domain, the dorsal border of cad20 overlapped with the Gsh1-domain (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Mapping of cad7 and cad20 expression on progenitor domains in the hindbrain. A-D: Expression analysis on the dissected whole brain (A, C) and cross-sections at r7 (B) and r6 level (D) of E11.5 embryo. Images of A and C are taken from the lateral side of the brain. At E11.5, cad7 mRNA is mainly detected in the dorsal domain of the neural tube posterior to r5/6 boundary (arrow in A), and the ventral border of cad7 corresponds to the dorsal border of Dbx2 (arrowhead in B, cross-section at r7 level after double detection). At E11.5, cad20 transcripts are highly detected in the middle domain of the hindbrain anterior to r6/7 boundary (arrow in C), and the dorsal area of cad20-domain overlaps with the ventral area of Gsh1-domain (arrowhead in D, cross-section at r6 level after double detection). E-J: Expression analysis on the dissected whole brain (E, I) and serial cross-sections at r7 level (F-H, and J) from E12.5 embryo. Images of E and I are taken from the lateral side of the brain. The ventral border of cad7 in the dorsal progenitor domain is consistent with the dorsal border of Dbx2 (arrowheads in F and G), and part of cad7-expressing progenitors gives rise to Lbx1-positive dorsal interneurons (Dl4-6) (H). The expression of cad20 in the middle domain of the hindbrain gradually disappears at E12.5 (I), and another expression domain of cad20 also appears in a more ventral region (arrow in I and J). K-L: BrdU detection after in situ hybridization. The domain of cad20-expressing cells corresponds to that of cells expressing Gata2, a V2 interneuron lineage maker (brackets in K and L), and cad20 expressing cells are progenitor cells incorporating BrdU (arrow in L). M-N: Summary of expression of cad7 and cad20 along D-V axis at E11.5 (M) and E12.5 (N). Left: expression domains at r5 and r7. Right: progenitor domains defined with expressions of homeodomain transcription factors and cadherins. Broken lines indicate the border between basal and alar plates. V0–V2, V0–V2 interneuron; SM, somatic motor neuron, BM, branchial motor neuron. Scale bars: 500 μm in A, C, E and I; 150 μm in B, D; 200 μm in F, G, H and J; 200 μm in K, L.

Even at E12.5, the expression domain of cad7 was clearly maintained in neuroepithelial cells in the dorsal hindbrain (Fig. 4E). The ventral border of cad7 coincided with the dorsal border of Dbx2, and the cad7 domain partially overlapped with the progenitor domains of the dorsal Lbx1-expressing interneurons [46] (Fig. 4F–H). Remarkably, a narrow longitudinal stripe of cad20 expression appeared in the ventral region of the hindbrain (Fig. 4I, J). This pattern was similar to the ventral expression of cad20 in the mouse embryo [28]. To elucidate the relationship between the expression domain of cad20 and the neural progenitor domain, we compared the expression of cad20 with several progenitor domain markers. The results showed similar expression patterns for transcription factor Gata2 in cad20 domain and the V2 interneuron progenitor domain (Fig. 4K, L) [47]. Cad20 expression was also detected in BrdU-incorporated S-phase cells (Fig. 4L). Taken together, these results suggest that cad7 and cad20 are expressed in different progenitor cells in the developing hindbrain.

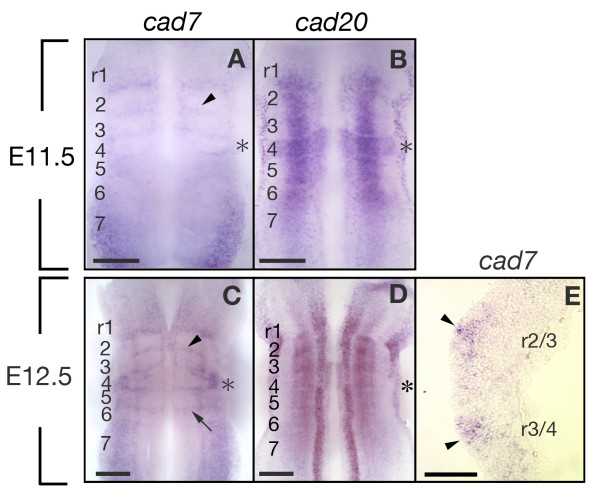

Cad7 expression delineates rhombomere boundaries

In the hindbrain, cells at the interface between each rhombomere are specialized as rhombomere boundary cells. Interestingly, the expression of cad7 was observed in the rhombomere boundary regions (Fig. 5A), while cad20 was continuously expressed along the r1–r7 with low level in r7 at E11.5 (Fig. 5B). In the caudal hindbrain, the expression of cad7 was downregulated in the ventral domain (Fig. 5A). In addition to longitudinal expression in the middle domain throughout the r1-7, cad20 specifically marked r4 at E11.5 (Fig. 5B). At E12.5, the cad7 expression was restricted to the rhombomere boundaries and to the dorsal region of the hindbrain (Fig. 5C). The transcripts of cad7 were accumulated in the cell body of boundary cells that are located in the apical side (Fig. 5E). The expression of cad20 was restricted in the ventral domains of the hindbrain (Fig. 5D). These results suggest possible distinct affinity of neuroepithelial cells mediated by cad7 and cad20 in the developing rat hindbrain along the A-P axis.

Figure 5.

Expression of cad7 and cad20 in the rhombomeres and boundaries. A-D: Expression of cad7 and cad20 in E11.5 (A, B) and E12.5 (C, D) hindbrains which are prepared in open-book style. Cad7 transcripts are localized in the boundaries (arrow and arrowhead in A, C). Cad20 is strongly expressed in the middle area in the r1-6 and r4 (asterisk in B). E: Horizontal section of whole-mount staining embryos with cad7 probe. Cad7 mRNA is highly expressed in the rhombomere boundary cells (arrowheads in E). Scale bars: 500 μm in A-D; 200 μm in E.

Cad7 and cad20 expression in motor neurons and precerebellar neurons at later developmental stages

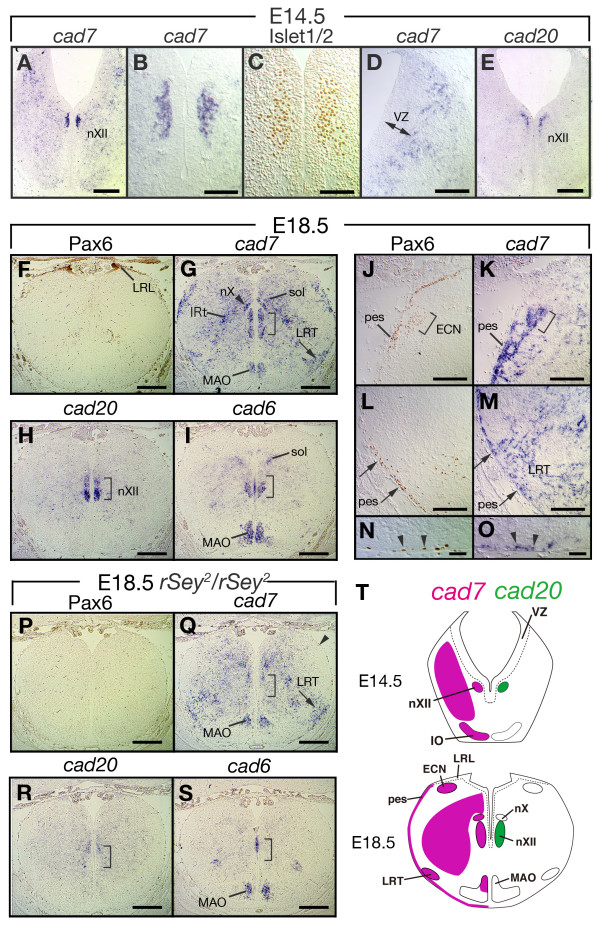

Previous studies of mouse and chick embryos showed the expression of subtypes of type I and type II classic cadherins in motor neurons and precerebellar neurons, and the involvement of such expression in the formation of each motor pool and in cell migration [24,25,31,48]. We examined the expression of cad7 and cad20 at later developmental stages in the hindbrain. At E14.5 in the caudal hindbrain, the expression of cad7 was downregulated in the ventricular zone but became detectable in the marginal zone (Fig. 6A, D). Judging from the expression of Islet1/2 in motor neurons, cad7 and cad20 were apparently expressed in the hypoglossal somatic motor nuclei (nXII) (Fig. 6B, C, E). At E18.5, cad7 expression extended beyond the nXII into the vagus motor nuclei (nX) (Fig. 6G). Cad20 was still expressed in the nXII at E18.5 (Fig. 6H). Cad7 was also expressed in the dorsal region including the nucleus of solitary tract (Sol) and in the intermediate reticular zone (IRt) (Fig. 6G).

Figure 6.

Expression of cad7 in the motor neurons and precerebellar systems. A-E: Expression of cad7 and cad20 on serial cross-sections from the hindbrain of E14.5 rat embryo at r7 level. (B) High magnification of the image shown in A. Expression of cad7 and cad20 is detected in hypoglossal motor nuclei (nXII) expressing Islet1/2 (A, B, C and E). No expression of cad7 is seen in the ventricular zone (VZ) of the dorsal area (D). F-O: Expression of Pax6, cad7 and cad20 on serial cross-sections at E18.5. Pax6 protein is detected in both the lower rhombic lip (LRL) (F), posterior extramural migrating stream (pes) (J and arrows in L) and the external cuneate nucleus (ECN) (bracket in J). Cad7 is expressed in nXII (bracket in G), vagus motor nuclei (nX) (arrowhead in G), lateral reticular nuclei (LRT) (arrow in G), the ECN (bracket in K), the nucleus of the solitary tract (Sol), and in the intermediate reticular zone (IRt). Cad7-expressing cells are migrating on the surface of the brain, which is similar to Pax6-expressing cells (arrows in L, M and arrowheads in N and O). Cad7 is also expressed in the medial accessory olive (MAO) nuclei expressing cad6 (G and I). Cad20 is expressed in nXII but not in nX (bracket in H). P-S: Serial cross-sections of E18.5 Pax6 homozygous mutant rat (rSey2/rSey2). Pax6 protein is undetectable (P), while expression of cad7 is detected in LRT (arrow in Q) and MAO expressing cad6 (S). nXII motor nuclei and ECN are missing in the Pax6 homozygous mutant (bracket and arrowhead in Q, respectively). The expression of cad20 is also undetectable, which is similar to the cad6 expression (bracket in R and S). T: Summary of expression of cad7 and cad20. Scale bars: 300 μm in A and E and F-I; 100 μm in B and C; 200 μm in D, J-M and P-S; 50 μm in N and O.

In the caudal hindbrain, the migratory stream to form precerebellar nuclei, called the posterior extramural migrating stream (pes), is visualized by the expression of certain makers including HD transcription factors such as Pax6 [49]. Pax6 is essential for the development of the cerebellum and formation of precerebellar nuclei [49-51]. At E18.5, Pax6 was expressed in the external cuneate nucleus (ECN) and the lateral reticular nucleus (LRT) (Fig. 6F, J, L). Interestingly, cad7 transcripts were also detected in the pes, ECN and LRT but not in the lower rhombic lip (LRL) (Fig. 6G, K, M, O). Cad7 mRNA expression was also detected in the cad6-expressing medial accessory olive (MAO) [25] but not in other parts of the inferior olive nucleus (IO) (Fig. 6I and 6G), and in the pontine nucleus (PN) and the reticular nucleus (RT) (Fig. 6A, B and Fig. 7A, B). We demonstrated previously that XII motor nuclei, ECN and PN were missing in the Pax6 homozygous mutant rat (rSey2/rSey2) [51,52]. In fact, the expression of cad7 was not detected in normal positions of the nXII, ECN or PN of rSey2/rSey2 embryo, although the expression was normally detected in LRT and MAO (Fig. 6P, Q, S and Fig. 7D). Furthermore, cad20 expression in the normal position of the nXII was not detected in rSey2/rSey2 embryo (Fig. 6R).

Figure 7.

Expression of cad7 in the brainstem and cerebellum in the foetus. A-J: Comparison of expression patterns of Pax6 and cad7 in the brainstem and cerebellum of the wild type (A, B, E and F) and Pax6 homozygous mutant rat (rSey2/rSey2) (C, D, G and H) on serial sagittal sections. At E20.5, Pax6 and cad7 are expressed in the pontine nucleus (PN), reticular nucleus (RT) (arrowheads in A and B) and the external germinal layer (EGL) (arrows in E and F). In the Pax6 mutant, cad7 expression is detected in the remaining RT (arrowhead in D), which is similar to Pax6 expression (arrowhead in C). The expression of Pax6 and cad7 is observed in EGL of the Pax6 mutant (arrows in G, H). I-L: Cross-sections of the E20.5 rat cerebellum. Cad7 is also expressed in the cerebellar neuroepithelium (cne) (arrows in J, bracket in L) and cerebellar deep nuclei (arrowheads in J) in contrast to the expression of Pax6 (I and K). M-N: Higher magnifications of E and F. The expression of Pax6 and cad7 is detected in both EGL (bracket) and migrating cells. URL, upper rhombic lip. Scale bars: 500 μm in A-D; 100 μm in E-H; 300 μm in I and J; 200 μm in K-M.

Cad7 expression in the external germinal layer of the cerebellum

Next, we examined the expression of cad7 in the developing cerebellum. At E20.5, cad7 expression overlapped with that of Pax6 in the external germinal layer (EGL) containing progenitors of granule cells that later migrate inwards from EGL (Fig. 7A, B, E, F, M, N). On the other hand, cad7 expression was not detected in the upper rhombic lip (URL) (Fig. 7F), but was identified in the deep cerebellar nucleus and the epithelium of the anterior hindbrain (Fig. 7J and 7L), which differed from the expression of Pax6 (Fig. 7I and 7K). Previous studies in the chick cerebellum at later embryonic stages have shown that cad7 transcripts are restricted to the Purkinje cell layer and internal granular layer (IGL) and are not in the EGL [53], and that the immunoreactivity of cad7 protein is absent in the ventricular zone of the developing cerebellum [54]. Considered together, the results suggest diversity of cad7 expression patterns in the chick and rat cerebellum.

It is has been reported that Pax6 regulates cell adhesion in the cerebral cortex [55,56] and cerebellar granule cell precursors [57]. R-cadherin is a downstream gene of Pax6 in the ventricular zone of the developing cerebral cortex [55]. Cad7 expression was still detected in EGL cells of the Pax6 homozygous mutant rat (Fig. 7D and 7H). These results suggest that cad7 expression in EGL is regulated by a Pax6-independent pathway.

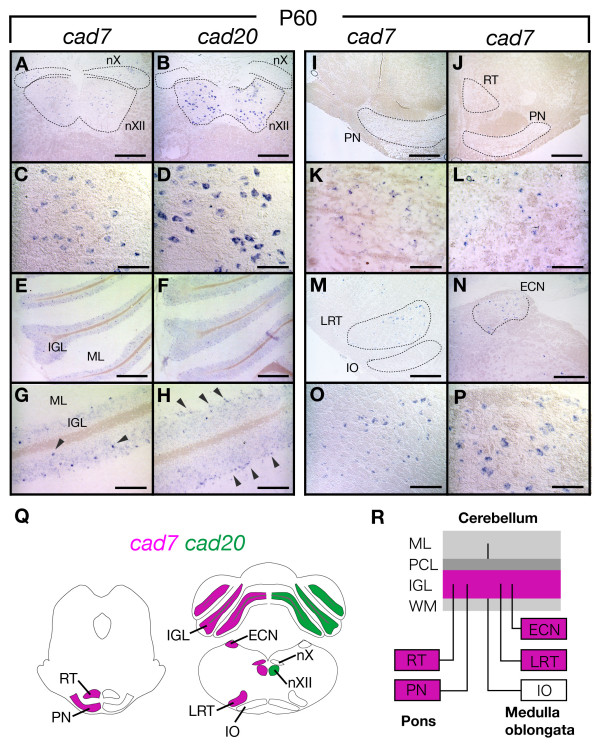

Cad7 and cad20 expression in the adult brainstem and cerebellum

In the adult brain, the precerebellar neurons and cerebellar granule cells make synaptic connections. Since cad7 was expressed in both precerebellar neurons and progenitors for granule cells, we examined its expression in these neuronal cells in the brainstem and cerebellum of the adult rat (Fig. 8). Cad7 was expressed in IGL, which contains granule cells, but not in Purkinje cells (Fig. 8E and 8G). We also observed scattered cells expressing cad7 at high levels in IGL (Fig. 8G). Cad7 was also expressed in PN and RT, ECN and LRT (Fig. 8I–P) but not in IO (Fig. 8M). On the other hand, cad20 was expressed in the IGL but not in the precerebellar nucleus (Fig. 8F, H). The expression of cad7 and cad20 in nX and nXII was maintained in adulthood (Fig. 8A and 8B). These results suggest that the expression of cad7 demarcates the precerebellar/cerebellar system in both embryonic and adult brain.

Figure 8.

Expression of cad7 in the brainstem and cerebellum in the adult. A-H: Expression of cad7 and cad20 in motor neurons and cerebellum on cross-sections of 8-week-old (P60) rat. The expression of cad7 is detected in both nX and nXII (A) but the expression of cad20 is only detected in nXII (B). C and D are high magnification images of cad7 and cad20 expression in nXII, which are indicated in A and B, respectively. In the cerebellum, cad7 and cad20 are expressed in the internal granular layer (IGL) (E, F), and scattered large cells expressing cad7 are detected in IGL (arrowheads in G, high magnification of E). Intense signal of cad20 is observed at the interface between molecular layer (ML) and IGL (arrowheads in H, high magnification of F). I-P: Expression of cad7 in the pons and medulla oblongata on cross-sections of the P60 rat. Expression of cad7 is detected in the pontine nucleus (PN) (I) and reticular nucleus (RT) (J). K and L are high magnification images of cad7 expression in the PN and RT indicated in I and J, respectively. Cad7 is expressed in the lateral reticular nuclei (LRT) and external cuneate nuclei (ECN) but not in the inferior olive nucleus (IO). O and P are high magnification of cad7-expressing cells in the LRT and ECN shown in M and N. Q-R: Summary of expression of cad7 and cad20 (Q) and schematic illustration showing the expression of cad7 and neuronal circuits in the hindbrain (R). Lines in R indicate connection between precerebellar neurons and layers of the cerebellum. PCL, Purkinje cell layer; WM, white matter. Scale bars: 500 μm in A, B, E, F, I, J; 400 μm in C, D, K, L, P; 200 μm in G, H, O; 500 μm in E, F, M, N.

Discussion

Expression of cad7 and cad20 in early brain subdivision

Wizenmann and Lumsden analyzed rhombomere cells of the chick embryo by re-aggregation assay and were the first to report that segregation of rhombomere neuroepithelial cells between even and odd rhombomeres was probably mediated by calcium-dependent molecules such as cadherins [58]. However, the candidate cadherin molecules expressed in specific rhombomeres or rhombomere boundary cells have not yet been identified in the chick embryo. On the other hand, other studies reported R-cad mRNA expression in the midbrain and odd number of rhombomeres, as well as cad6 expression in even number of rhombomeres in the mouse neural plate [36,37]. Interestingly, in our analysis, we found specific expression of cad20 in the r2 of the rat embryo at E10.5 (Fig. 3) and that the posterior limit of cad7 expression was consistent with that of Otx2 at E10.5 (Fig. 3). Taking into consideration the transient expression of R-cad and cad6 at early stages and distinct cell adhesiveness of different cadherins, it is conceivable that classic cadherin subtypes including cad20 are involved in segregation of cells at the interface between rhombomeres in rodent embryos. Taken together, it is likely that distinct cadherin subtypes mediate compartmentalization, although further studies are needed to confirm this conclusion.

Lineage restriction of neuroepithelial cells in diencephalic subdivisions has been elucidated in the chick embryo [6,59]. The chick diencephalon is firstly subdivided into three regions; the presumptive pretectum, dorsal thalamus, and ventral thalamus. Previous studies suggested that differential expression of types I and II cadherins demarcates diencephalic subdivisions in the chick and mouse embryos [11,12,34,60]. In the present study, the expression of cad7 overlapped with that of cad20 in the rat neural plate in the forebrain region. Furthermore, a previous cell lineage analysis suggested that the midbrain/diencephalon boundary restricts cell mixing [61,62], and that cad6 delineates the midbrain/diencephalon boundary in the mouse neural plate [62]. In fact, the posterior border of cad7 became clearer at E11.5 compared with at E10.5 and the sharp expression boundary was maintained at E12.5 as in the case of Otx2 expression (Fig. 2E, I). Otx2 regulates the cell adhesion property of neuroepithelial cells in mice [37], and overexpression of Otx can induce cell aggregation in zebrafish embryos [63]. ZLI is not a cell population derived from specialized cells at p2/3 boundary, but is itself a compartment that originates from the area that does not express Lunatic fringe (L-fng) [64]. The p2/3 border is demarcated by the expression of Six3 and Irx3 in the early neural plate [40], where ZLI is established. However, in the early neural plate, whether the p2/3 boundary restricts cell mixing has not been elucidated in both avian and rodent embryos. Interestingly, we found that the posterior border of cad20 expression was consistent with the p2/3 border, which is mediated by mutual repression of Six3/Fez1/Fez like1 and Irx3/Irx1 (Fig. 3) [40,65]. Our finding suggests the involvement of cad20 restricted expression in establishment of ZLI-signalling centre formed at the p2/3 boundary.

Expression of cad7 and cad20 in the hindbrain progenitor domains and rhombomere boundary

Although the hindbrain and spinal cord are subdivided into the basal and alar plates at the sulcus limitans defined by a morphological groove in the vertebrates, a recent study using molecular markers has shown that the basal/alar boundary corresponds to the dorsal border of cad7 expression in the chick neural tube [22]. Our study showed that longitudinal expression of cad20 resembles those of chick cad7 and Xenopus F-cad at the hindbrain level (Fig. 4) [18,20] and that the sulcus limitans in the rat hindbrain is somewhat related to the expression of cad20. Remarkably, along the anterior-posterior (A-P) axis, cad20 mRNA expression was gradually downregulated in the basal plate from r7 to the spinal cord, and restricted in V2 interneuron progenitor cells (Fig. 5). Moreover, the cad7-expressing domain continued through the caudal hindbrain to the spinal cord (Figs. 2, 4 and 5), suggesting that the basal/alar boundary could be established or maintained by distinct cadherin subtypes in the rostral hindbrain and spinal cord. It was noteworthy that both cad7 and cad20 were expressed at r6 in E11.5 along the D-V axis (Fig. 4), and double staining for Dbx2/cad7 and Gsh1/cad20 showed partial overlap of cad7 and cad20 expression at r6 level in the E11.5 hindbrain (Fig. 4). Since heterophilic adhesion has been reported within distinct type II cadherins [17], and EC1, which is a critical sequence for calcium-dependent adhesion, is highly conserved between cad7 and cad20 proteins (Fig. 1), determination of the adhesion properties of cad7 and cad20 proteins should be the next research priority.

In the ventral spinal cord and hindbrain, transcription factors such as Pax, Nkx and Dbx families regulate the formation of progenitor domains by HD codes and specification of neuronal subtypes by mutual repression activities [7,43]. In the chick spinal cord, ectopically expressed Pax7 can repress cad7 in the ventral region and Shh can induce cad7 in the dorsal region [66]. Therefore, it is possible that rat cad7 and cad20 are regulated by Shh signalling pathway.

A previous study indicated that segregation of boundary cells is mediated by radical fringe-mediated activation of the Notch signalling pathway in the zebrafish hindbrain [67]. In the mouse, although three fringe genes are not expressed at rhombomere boundaries [68], expression of Hes1, a target gene of Notch signalling, persists at high levels in boundary cells in the hindbrain [69]. Rhombomere boundary cells exhibit a static feature contrary to rhombomere centre cells, i.e., a slow rate of proliferation and interkinetic nuclear migration, and their nuclei are located on the ventricular surface [70]. Since cad7 expression in rhombomere boundaries actually starts after the formation of boundaries, such expression at rhombomere boundaries implicates differential cell adhesiveness between boundary and non-boundary cells in maintenance of boundary cells. Considering the expression of cad7 in ZLI, a boundary in the chick diencephalon [34], our findings could be interpreted to mean that cadherin-mediated cell-to-cell contact serves to restrict intermingling of boundary cells and compartment cells, thereby maintaining boundary regions.

Expression of cad7 in precerebellar neurons and cerebellum during late embryonic and adult periods

Interestingly, the expression of cad7 and cad20 mRNAs in the neuroepithelium disappeared by E14.5, and their expression was detected in postmitotic neurons in the pons and medulla oblongata (Figs. 6 and 7). Previous studies reported that cadherins also contribute to cell migration in the brain [48]. In the cerebellum, Purkinje cells are generated from epithelial progenitor cells and migrate to the deep layer [71]. Experimentally, cad7 and cad6b-overexpressed progenitor cells preferentially migrated into Purkinje cell domain, which endogenously expresses these cadherins in the chick cerebellum [72]. The lower RL cells generate four types of precerebellar neurons to form the pontine, reticulotegmental, lateral reticular and external cuneate nuclei [73,74]. These precerebellar neurons project to the granule cells in the cerebellum [71]. The dorsal cells of the caudal hindbrain generate the inferior olive neurons, and express cadherin subtypes, e.g., cad6, cad8 and cad11 [23,24]. Interestingly, at later stages, we observed switching of cad7 expression from epithelial cells to migrating postmitotic neurons. Although the expression of various cadherin subtypes in precerebellar neurons had been reported previously [48], the expression of cad7 was more specifically detected than that of other cadherins in all precerebellar nuclei. Neurons expressing cad7 (X/XII cranial motor neurons, pontine and external cuneate neurons) aggregated at late embryonic stages (Figs. 6 and 7), suggesting the involvement of cad7 in cell sorting mechanisms, in agreement with the functions of type II classic cadherin subtypes in the chick spinal cord [31].

We found sparse cad7 expression in precerebellar neurons in the adult hindbrain (Fig. 8). The cadherin-catenin complex including N-cadherin/αN-catenin is involved in the formation of synaptic contact [26,75]. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that type II subtypes, cad11 and cad13, also have specific roles in synaptic function including modulation of long-term potential and neurotransmission [76,77], and that cad8 has an important role in transmission of sensory information from sensory neurons to the dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord [78]. Therefore, the expression pattern of cad7 in the hindbrain and cerebellum suggests that cad7 may physiologically modulate the cerebellar/precerebellar neural circuitry.

Genomic organization of cad20/cad19/cad7 cluster and expression among different species

Cadherin family genes evolutionally duplicated [79] and formed as several clusters on chromosomes [80,81]. In the human genome, CDH5 (VE-cad)/CDH1 (E-cad)/CDH3 (P-cad) and CDH8/CDH11/CDH13/CDH15 are located on chromosome 16q21/22 [80], and CDH20/CDH19/CDH7 are clustered on 18q22-23 [30]. Comparison of the expression of such clustered cadherin genes among distinct species is important in order to identify common control element. However, our results showed that the distribution of rat cad7 and cad19 to that of cad20 was inconsistent with the localization of their homologues in the chick (Fig. 1, Table 1). Chick cad7 is also expressed in neural crest-derived cells as well as in the ventral neural tube [20,21]. Our previous and present studies showed that cad19 but not cad7 was expressed in the neural crest cell lineage at the trunk level in the rat [27], suggesting that the distribution of cad7 and cad19 genes is associated with their expression patterns. However, the expression of chick cad19 was detected in part of neural crest-derived cells and neural tube but not in the dorsal domain and rhombomere boundary cells in the hindbrain (our unpublished observation). Taken together, our analysis suggests that the expression patterns of clustered cad20/cad19/cad7 genes are regulated by species-specific gene regulatory elements in avian and rodent embryos, which is in contrast to the highly conserved expression patterns of HD protein genes in the central nervous system.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that cell populations that express cad7 and cad20 are diversified in the rat and chick. The expression of these cadherin subtypes demarcates compartments, boundaries, progenitor domains, specific nuclei and circuits during mammalian hindbrain development.

Methods

Animals

Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals. The Committee for Animal Experiments of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine approved the experimental procedures described in this study. The midday of the vaginal plug was designated as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Pregnant Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from Charles River Japan. Pax6 homozygous mutant rat embryos were obtained by crossing of male and female Small eye rat heterozygotes (rSey2/+) [52], which were maintained at Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine.

Identification of rat cad7 and cad20

Rat cad7 and cad20 genomic sequences were identified through BLAST genome search of NCBI and BLAT database at UCSC Genome Bioinformatics. cDNA fragments encoding ORF of rat cad7 and cad20 were amplified by RT-PCR using oligonucleotide primers designed based on the identified rat genomic sequences. Total RNA taken from the head including the hindbrain of E12.5 rat embryos was purified with RNeasy column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and cDNA was synthesized using oligo dT primer and reverse transcriptase (Superscript II, Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The primer sets were as follow: 5' fragment of cad7 (1–1467: 5'-ATGAAGCTGGGCAAAGTGGAG-3' and 5'-AGTGGTTTCATACTCCATGGC-3'), 3' fragment of cad7 (1447–2361: 5'-GCCATGGACTATGAAACCACT-3' and 5'-AGGCTATGAGTACAAACTCTC-3'), 5' fragment of cad20 (1–1071: 5'-ATGTGGACTACAGGTAGAATG-3' and 5'-ATTGGATCCTTCCACCTTCAG-3'), and 3' fragment of cad20 (1051–2450: 5'-CTGAAGGTGGAAGGATCCAAT-3' and 5'-TGAGAACGTCTGGATTTGGGT-3'). Amplification was performed using a thermal cycler (Mastercycler gradient; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) using Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) under the following conditions: denaturation for 5 min at 96°C, annealing for 1 min at 63.5°C (cad7), 60.8°C (cad20), extension for 1 min at 72°C, 35 cycles. The amplified products were blunted using T4 DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and inserted into EcoR V site of pBluescript SKII (-). DDBJ accession numbers are AB121031 (rat cad7) and AB121033 (rat cad20).

Alignments and phylogenetic analysis of cadherin family

Multiple alignment of amino acid sequences of Cad7 and Cad20 and phylogenetic analysis for full length of amino acid sequences of type II classic cadherins were performed by Clustal W program and gene database. The gene accession numbers of cadherins used to characterize protein sequences are AB121032 (rat cad19), AJ007607 (human cad19), X95600 (mouse cad8), D21253 (mouse cad11), D252990 (rat K-cad/cad6), D82029 (mouse cad6), D42149 (chick cad6b), AB035301 (human cad7), AK034096 (mouse cad7), D42150 (chick cad7), AF217289 (human cad20), AF007116 (mouse cad20), AF459439 (chick MN-cad, the same sequence is identified as the chick F-cadherin homolog, AF465257), X85330 (Xenopus F-cad), L33477 (human cad12/Br-cad), XP_226899 (rat cad18), XP_001054792 (rat cad24/EY-cad), AY260900 (human cad24) and NM_019161 (rat cad22). Phylogenetic tree was drawn by Tree View software (Taxonomy and Systematics at Glasgow). The scale bar was set to represent 10% differences.

Cloning of rat cDNAs encoding transcription factors

To obtain rat Gsh1, Krox20 and Gbx2 cDNAs, the corresponding genomic sequence was amplified by genomic PCR using oligonucleotide primers. Rat Dbx2 and Lbx1 cDNAs were amplified by RT-PCR using mRNA prepared from E12.5 SD rat embryos. Primer sets were designed based on the sequences, which are homologous to mouse Gsh1, rat Krox20, rat Gbx2, mouse Dbx2 and mouse Lbx1 mRNAs. Used oligonucleotide primers were as follow, Gsh1 (5'-CAGCAGCAGCCAAGGTGATT-3' and 5'-CCACGGAGATGCAGTGAAAC-3'), Krox20 (5'-TCAACATTGACATGACCGGAG-3' and 5'-GAATGAGACCTGGGTCCATAG-3'), Gbx2 (5'-ACGAGTCAAAGGTGGAAGATG-3' and 5'-TGACTTCGAATAGCGAACCTG-3'), Dbx2 (5'-TGCTGACCCAGGACTCAAATT-3' and 5'-GGATACCAAAGAAGCCAGAAG-3') and Lbx1 (5'-GAGATGACTTCCAAGGAGGAC-3' and 5'-ATCAGGCTGTAGTGGAAGGAA-3'). Amplification was performed under following conditions: denaturation for 5 minutes at 96°C, annealing for 1 min at 68.1°C (Gsh1), 55.5°C (Krox20), 60.8°C (Gbx2), 60.8°C (Dbx2) and 60.8°C (Lbx1), extension for 1 min at 72°C, 35 cycles. To clone the amplified products, these fragments were blunted using T4 DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and inserted into EcoR V site of pBluescript SKII (-) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Cloned cDNAs were confirmed by sequencing. DDBJ accession numbers are AB197922 (rat Gsh1), AB264614 (rat Krox20), AB266843 (rat Gbx2), AB121147 (rat Dbx2) and AB197923 (rat Lbx1).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as described previously [27,52]. Dissected embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/phosphate buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled riboprobes were synthesized by in vitro transcription with DIG RNA labelling mix (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and T3 or T7 RNA polymerase (Promega). All synthesized probes were purified with Quick Spin Columns G-25 (RNA) (Roche) to remove unincorporated nucleotides. For detection of cad7 mRNA, three kinds of probes transcribed from different cad7 cDNA fragments (1–460, 567–1460 and 1992–2361) were used in hybridization. To detect cad20 mRNA, four kinds of probes transcribed from different cad20 cDNA fragments (1–546, 1051–1497, 1639–1956 and 2014–2403) were mixed in hybridization. Two-colour whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed using the protocol described on the internet http://www.anat.ucl.ac.uk/research/sternlab/INSITU.htm. For double colour detection, fluorescein-labelled riboprobes for Dbx2, Gsh1, Otx2 and Gbx2 were generated with fluorescein RNA labelling mix (Roche), and simultaneously hybridized with DIG-labelled cad7 or cad20 riboprobes, respectively. After the first colour reaction with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (1:5000, Roche) and NBT/BCIP (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), embryos were fixed in 4% PFA/PBS at room temperature overnight and incubated in TBST containing 0.1% Tween20 at 65°C for 1 hour to inactivate AP completely. The second colour signal was detected with AP-conjugated anti-fluorescein antibody (1:5000, Roche) and INT/BCIP (Roche). Drs. I. Matsuo, A. Mansouri and P. Gruss kindly provided mouse Otx2, Six3 and Irx3 cDNAs for synthesis of riboprobes, respectively. Images were recorded by cooled colour CCD camera (Penguin 600CL, Pixera, San Jose, CA).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization using frozen sections of embryonic tissues was performed as described previously [43]. E12.5 whole rat embryos and heads of E14.5 and E18.5 embryos were fixed in 4% PFA/PBS overnight at °C. For fixation of E20.5 rat foetuses, the brains were dissected and fixed without the pia mater in 4% PFA/PBS overnight. Embryos and foetuses were embedded with optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura, Tokyo) and cut into 12 μm sections with a cryostat (Leica, Nussloch, Germany). DIG-labelled riboprobes were synthesized with T3 or T7 (Promega) or SP6 (Takara Shuzo, Ohtsu, Japan) RNA polymerase and hybridized to sections. To detect the expression of cad7 mRNA, two kinds of riboprobes of cad7 were generated from different cDNA fragments (1–1467 and 1447–2361), and mixed in hybridization. Riboprobes of cad20 were synthesized by from two cDNA fragments (1–1071 and 1051–2450), and used simultaneously in hybridization. Mouse Gata2, rat cad6/K-cad [82] and rat Sox10 cDNAs were kindly provided by Drs. M. Yamamoto, M. Tanaka and M. Wegner, respectively. For in situ hybridization of the adult brain, 8-week-old male adult rats (postnatal day 60) were deeply anesthetized and decapitated. Brains were immediately dissected out and frozen on powder dry ice. The brains were cut into 14 μm sections, and were post-fixed in 4% PFA/PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. Sections were acetylated with tri-ethanoamine, HCl and acetic acid for 10 min. The following strategies of hybridization and staining were performed according to the protocol described for embryonic tissues except for changing the concentration of AP-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (1:2000). Images were recorded with colour CCD camera (HC-25000 3CCD, Fuji, Tokyo).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry using frozen sections was performed as described previously [52]. Embryos and foetuses were fixed as described above for in situ hybridization. Antigen-enhanced sections, which were boiled in 0.1 M citric acid solution in a microwave, were incubated with anti-Pax6 rabbit polyclonal antibody [62] (1:500) and anti-Islet1/2 mouse monoclonal antibody (D.S.H.B, 40.2D6, 1:100), which were diluted with 2% goat serum/TBST overnight at 4°C. As secondary antibodies, biotin-conjugated affinity purified anti-rabbit IgG (dilution, 1:200, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and anti-mouse IgG donkey antibodies (1:200, Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, CA) were used. Signal was enhanced by combination of ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and enhanced DAB kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). After in situ hybridization for Sox10 and cad7, sections were incubated with anti-neuron-specific class III β-tubulin antibody (1:2000, Tuj1, MMS-435P, Covance, Madison, WI), and the signal was detected by using Cy3-conjugated affinity purified anti-mouse IgG donkey antibody (1:400, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Images were recorded with AxioPlanII and AxioCamMRm (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

BrdU labelling using whole embryo cultures

Short pulse labelling of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for cultured rat embryos was performed as described previously [43]. E12.5 rat embryos were precultured for 1 hour and BrdU solution was directly added to the culture medium. Embryos were exposed to BrdU for 20 min and fixed in 4% PFA/PBS. After detection of Gata2 mRNA by in situ hybridization, sections were treated with 2N HCl solution for 15 min at 37°C and neutralized in TBST. Sections were incubated with anti-BrdU mouse monoclonal antibody (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, 1:50), and the signal was detected with ABC kit and enhanced DAB kit.

Authors' contributions

MT designed and carried out all experiments in Osumi lab. MT and NO discussed the results and wrote the manuscript together.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Sayaka Makino, Ms. Yumi Watanabe and Dr. Yoko Arai for technical support, and Dr. Takayoshi Inoue for critical reading and valuable comments. We also thank Drs. Isao Matsuo, Ahmed Mansouri, Peter Gruss, Masamitsu Tanaka and Masayuki Yamamoto for providing reagents used in this study. Islet1/2 antibody was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242. We also thank all other members of Prof. Osumi laboratory for valuable comments and discussion. This work was supported by KAKENHI on Priority Areas-A nuclear system to DECODE (#17054003 to M.T), Molecular Brain Science (#17024001 to N.O.) and on Young Scientist Research B (#17700300 and #20700281 to M.T.) from MEXT of Japan, The Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology from Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST) (to N.O), Global COE Program "Basic and Translational Research Center for Global Brain Science" of MEXT and GONRYO Foundation for the promotion of medical Science (to. M.T.).

Contributor Information

Masanori Takahashi, Email: mtaka@mail.tains.tohoku.ac.jp.

Noriko Osumi, Email: osumi@mail.tains.tohoku.ac.jp.

References

- Pasini A, Wilkinson DG. Stabilizing the regionalisation of the developing vertebrate central nervous system. Bioessays. 2002;24:427–38. doi: 10.1002/bies.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecker C, Lumsden A. Compartments and their boundaries in vertebrate brain development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:553–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S, Keynes R, Lumsden A. Segmentation in the chick embryo hindbrain is defined by cell lineage restrictions. Nature. 1990;344:431–5. doi: 10.1038/344431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL, Martinez S, Shimamura K, Puelles L. The embryonic vertebrate forebrain: the prosomeric model. Science. 1994;266:578–80. doi: 10.1126/science.7939711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puelles L, Rubenstein JL. Forebrain gene expression domains and the evolving prosomeric model. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:469–76. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figdor MC, Stern CD. Segmental organization of embryonic diencephalon. Nature. 1993;363:630–4. doi: 10.1038/363630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Pierani A, Jessell TM, Ericson J. A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2000;101:435–45. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redies C, Treubert-Zimmermann U, Luo J. Cadherins as regulators for the emergence of neural nets from embryonic divisions. J Physiol (Paris) 2003;97:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redies C, Engelhart K, Takeichi M. Differential expression of N- and R-cadherin in functional neuronal systems and other structures of the developing chicken brain. J Comp Neurol. 1993;333:398–416. doi: 10.1002/cne.903330307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura K, Hirano S, McMahon AP, Takeichi M. Wnt-1-dependent regulation of local E-cadherin and alpha N-catenin expression in the embryonic mouse brain. Development. 1994;120:2225–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzler SI, Redies C. R-cadherin expression during nucleus formation in chicken forebrain neuromeres. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4157–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04157.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redies C, Takeichi M. Cadherins in the developing central nervous system: an adhesive code for segmental and functional subdivisions. Dev Biol. 1996;180:413–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi T, Takeichi M. Cadherin superfamily genes: functions, genomic organization, and neurologic diversity. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1169–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SD, Chen CP, Bahna F, Honig B, Shapiro L. Cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion: sticking together as a family. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:690–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi M. Morphogenetic roles of classic cadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:619–27. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami H, Miyatani S, Inoue T, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Takeichi M. Cell binding specificity of mouse R-cadherin and chromosomal mapping of the gene. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:401–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoyama Y, Tsujimoto G, Kitajima M, Natori M. Identification of three human type-II classic cadherins and frequent heterophilic interactions between different subclasses of type-II classic cadherins. Biochem J. 2000;349:159–67. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeseth A, Johnson E, Kintner C. Xenopus F-cadherin, a novel member of the cadherin family of cell adhesion molecules, is expressed at boundaries in the neural tube. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6:199–211. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espeseth A, Marnellos G, Kintner C. The role of F-cadherin in localizing cells during neural tube formation in Xenopus embryos. Development. 1998;125:301–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Takeichi M. Neural crest cell-cell adhesion controlled by sequential and subpopulation-specific expression of novel cadherins. Development. 1995;121:1321–32. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Takeichi M. Neural crest emigration from the neural tube depends on regulated cadherin expression. Development. 1998;125:2963–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju MJ, Aroca P, Luo J, Puelles L, Redies C. Molecular profiling indicates avian branchiomotor nuclei invade the hindbrain alar plate. Neuroscience. 2004;128:785–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Tanaka T, Takeichi M, Chisaka O, Nakamura S, Osumi N. Role of cadherins in maintaining the compartment boundary between the cortex and striatum during development. Development. 2001;128:561–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki SC, Inoue T, Kimura Y, Tanaka T, Takeichi M. Neuronal circuits are subdivided by differential expression of type-II classic cadherins in postnatal mouse brains. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:433–47. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Tanaka T, Suzuki SC, Takeichi M. Cadherin-6 in the developing mouse brain: expression along restricted connection systems and synaptic localization suggest a potential role in neuronal circuitry. Dev Dyn. 1998;211:338–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199804)211:4<338::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi M, Abe K. Synaptic contact dynamics controlled by cadherin and catenins. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Osumi N. Identification of a novel type II classical cadherin: rat cadherin19 is expressed in the cranial ganglia and Schwann cell precursors during development. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:200–8. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Champeval D, Denat L, Tan SS, Faure F, Julien-Grille S, Larue L. Involvement of cadherins 7 and 20 in mouse embryogenesis and melanocyte transformation. Oncogene. 2004;23:6726–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner-Jones BE, Godinho LN, Reese BE, Pasquini GF, Ruefli A, Tan SS. Cloning and expression of mouse Cadherin-7, a type-II cadherin isolated from the developing eye. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:1–16. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kools P, Van Imschoot G, van Roy F. Characterization of three novel human cadherin genes (CDH7, CDH19, and CDH20) clustered on chromosome 18q22-q23 and with high homology to chicken cadherin-7. Genomics. 2000;68:283–95. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price SR, De Marco Garcia NV, Ranscht B, Jessell TM. Regulation of motor neuron pool sorting by differential expression of type II cadherins. Cell. 2002;109:205–16. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00695-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirabe K, Kimura Y, Matsuo N, Fukushima M, Yoshioka H, Tanaka H. MN-cadherin and its novel variant are transiently expressed in chick embryo spinal cord. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Wang H, Lin J, Redies C. Cadherin expression in the developing chicken cochlea. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2331–7. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon MS, Puelles L, Redies C. Formation of cadherin-expressing brain nuclei in diencephalic alar plate divisions. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:461–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(20000612)421:4<461::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlbrodt K, Herbarth B, Sock E, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Wegner M. Sox10, a novel transcriptional modulator in glial cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:237–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00237.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Chisaka O, Matsunami H, Takeichi M. Cadherin-6 expression transiently delineates specific rhombomeres, other neural tube subdivisions, and neural crest subpopulations in mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1997;183:183–94. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhinn M, Dierich A, Le Meur M, Ang S. Cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous functions of Otx2 in patterning the rostral brain. Development. 1999;126:4295–304. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG, Bhatt S, Chavrier P, Bravo R, Charnay P. Segment-specific expression of a zinc-finger gene in the developing nervous system of the mouse. Nature. 1989;337:461–4. doi: 10.1038/337461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver G, Mailhos A, Wehr R, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Gruss P. Six3, a murine homologue of the sine oculis gene, demarcates the most anterior border of the developing neural plate and is expressed during eye development. Development. 1995;121:4045–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi D, Kobayashi M, Matsumoto K, Ogura T, Nakafuku M, Shimamura K. Early subdivisions in the neural plate define distinct competence for inductive signals. Development. 2002;129:83–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone A. Positioning the isthmic organizer where Otx2 and Gbx2meet. Trends Genet. 2000;16:237–40. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02000-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwolf GC, Smith JL. Mechanisms of neurulation: traditional viewpoint and recent advances. Development. 1990;109:243–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Osumi N. Pax6 regulates specification of ventral neurone subtypes in the hindbrain by establishing progenitor domains. Development. 2002;129:1327–38. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerius MT, Li H, Stock JL, Weinstein M, Kaur S, Singh G, Potter SS. Gsh-1: a novel murine homeobox gene expressed in the central nervous system. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:337–51. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji H, Ito T, Wakamatsu Y, Hayasaka N, Ohsaki K, Oyanagi M, Kominami R, Kondoh H, Takahashi N. Regionalized expression of the Dbx family homeobox genes in the embryonic CNS of the mouse. Mech Dev. 1996;56:25–39. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00509-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms AW, Johnson JE. Specification of dorsal spinal cord interneurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:42–9. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(03)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Yamamoto M, Engel JD. GATA2 is required for the generation of V2 interneurons. Development. 2000;127:3829–38. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, Kawauchi D, Nishida K, Murakami F. Classic cadherins regulate tangential migration of precerebellar neurons in the caudal hindbrain. Development. 2006;133:1923–31. doi: 10.1242/dev.02354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelkamp D, Rashbass P, Seawright A, van Heyningen V. Role of Pax6 in development of the cerebellar system. Development. 1999;126:3585–96. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.16.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki T, Kawaji K, Ono K, Bito H, Hirano T, Osumi N, Kengaku M. Pax6 regulates granule cell polarization during parallel fiber formation in the developing cerebellum. Development. 2001;128:3133–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie M, Sango K, Takeuchi K, Honma S, Osumi N, Kawamura K, Kawano H. Subpial neuronal migration in the medulla oblongata of Pax-6-deficient rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:49–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osumi N, Hirota A, Ohuchi H, Nakafuku M, Iimura T, Kuratani S, Fujiwara M, Noji S, Eto K. Pax-6 is involved in the specification of hindbrain motor neuron subtype. Development. 1997;124:2961–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt K, Nakagawa S, Takeichi M, Redies C. Cadherin-defined segments and parasagittal cell ribbons in the developing chicken cerebellum. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;10:211–28. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt K, Redies C. Development of cadherin-defined parasagittal subdivisions in the embryonic chicken cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. 1998;401:367–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19981123)401:3<367::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoykova A, Gotz M, Gruss P, Price J. Pax6-dependent regulation of adhesive patterning, R-cadherin expression and boundary formation in developing forebrain. Development. 1997;124:3765–77. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.19.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas DA, Pearson H, Rashbass P, Price DJ. Pax6 regulates cell adhesion during cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:612–9. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.6.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DJ, Tong Y, Goldowitz D. Disruption of cerebellar granule cell development in the Pax6 mutant, Sey mouse. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;160:176–93. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wizenmann A, Lumsden A. Segregation of Rhombomeres by Differential Chemoaffinity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:448–59. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen CW, Zeltser LM, Lumsden A. Boundary formation and compartition in the avian diencephalon. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4699–711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04699.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami H, Takeichi M. Fetal brain subdivisions defined by R- and E-cadherin expressions: evidence for the role of cadherin activity in region-specific, cell-cell adhesion. Dev Biol. 1995;172:466–78. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.8029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas M, Millet S, Ahn S, Joyner AL. Cell behaviors and genetic lineages of the mesencephalon and rhombomere 1. Neuron. 2004;43:345–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Nakamura S, Osumi N. Fate mapping of the mouse prosencephalic neural plate. Dev Biol. 2000;219:373–83. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellipanni G, Murakami T, Doerre OG, Andermann P, Weinberg ES. Expression of Otx homeodomain proteins induces cell aggregation in developing zebrafish embryos. Dev Biol. 2000;223:339–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltser LM, Larsen CW, Lumsden A. A new developmental compartment in the forebrain regulated by Lunatic fringe. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:683–4. doi: 10.1038/89455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata T, Nakazawa M, Muraoka O, Nakayama R, Suda Y, Hibi M. Zinc-finger genes Fez and Fez-like function in the establishment of diencephalon subdivisions. Development. 2006;133:3993–4004. doi: 10.1242/dev.02585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Ju MJ, Redies C. Regionalized cadherin-7 expression by radial glia is regulated by Shh and Pax7 during chicken spinal cord development. Neuroscience. 2006;142:1133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YC, Amoyel M, Qiu X, Jiang YJ, Xu Q, Wilkinson DG. Notch activation regulates the segregation and differentiation of rhombomere boundary cells in the zebrafish hindbrain. Dev Cell. 2004;6:539–50. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston SH, Rauskolb C, Wilson R, Prabhakaran B, Irvine KD, Vogt TF. A family of mammalian Fringe genes implicated in boundary determination and the Notch pathway. Development. 1997;124:2245–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek JH, Hatakeyama J, Sakamoto S, Ohtsuka T, Kageyama R. Persistent and high levels of Hes1 expression regulate boundary formation in the developing central nervous system. Development. 2006;133:2467–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.02403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie S, Butcher M, Lumsden A. Patterns of cell division and interkinetic nuclear migration in the chick embryo hindbrain. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:742–54. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldowitz D, Hamre K. The cells and molecules that make a cerebellum. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:375–82. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Treubert-Zimmermann U, Redies C. Cadherins guide migrating Purkinje cells to specific parasagittal domains during cerebellar development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25:138–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the precerebellar nuclei in the rat: III. The posterior precerebellar extramural migratory stream and the lateral reticular and external cuneate nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 1987;257:513–28. doi: 10.1002/cne.902570404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the precerebellar nuclei in the rat: IV. The anterior precerebellar extramural migratory stream and the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis and the basal pontine gray. J Comp Neurol. 1987;257:529–52. doi: 10.1002/cne.902570405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannon AM, Colman DR. A model for central synaptic junctional complex formation based on the differential adhesive specificities of the cadherins. Neuron. 1996;17:423–34. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Togashi H, Uchida N, Suzuki SC, Hayakawa Y, Yamamoto M, Yoda H, Miyakawa T, Takeichi M, Chisaka O. Loss of cadherin-11 adhesion receptor enhances plastic changes in hippocampal synapses and modifies behavioral responses. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:534–46. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis S, Harrar DB, Lin Y, Koon AC, Hauser JL, Griffith EC, Zhu L, Brass LF, Chen C, Greenberg ME. An RNAi-based approach identifies molecules required for glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse development. Neuron. 2007;53:217–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki SC, Furue H, Koga K, Jiang N, Nohmi M, Shimazaki Y, Katoh-Fukui Y, Yokoyama M, Yoshimura M, Takeichi M. Cadherin-8 is required for the first relay synapses to receive functional inputs from primary sensory afferents for cold sensation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3466–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0243-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Makabe K. Genome duplications of early vertebrates as a possible chronicle of the evolutionary history of the neural crest. Int J Biol Sci. 2006;2:133–41. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst BD, Marcozzi C, Magee AI. The cadherin superfamily: diversity in form and function. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:629–41. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollet F, Kools P, van Roy F. Phylogenetic analysis of the cadherin superfamily allows identification of six major subfamilies besides several solitary members. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:551–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang YY, Tanaka M, Suzuki M, Igarashi H, Kiyokawa E, Naito Y, Ohtawara Y, Shen Q, Sugimura H, Kino I. Isolation of complementary DNA encoding K-cadherin, a novel rat cadherin preferentially expressed in fetal kidney and kidney carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3034–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]