Abstract

Caspases are cysteine proteases that are essential for cytokine maturation and apoptosis. To facilitate the dissection of caspase function in vitro and in vivo, we have synthesized irreversible caspase inhibitors with biotin attached via linker arms of various lengths (12a–d) and a 2,4-dinitrophenyl labeled inhibitor (13). Affinity labeling of apoptotic extracts followed by blotting reveals that these affinity probes detect active caspases. Using the strong affinity of avidin for biotin, we have isolated affinity-labeled caspase-6 from apoptotic cytosolic extracts of cells overexpressing procaspase 6 by treatment with 12c, which contains biotin attached to the Nε-lysine of the inhibitor by a 22.5 Å linker arm, followed by affinity purification on monomeric avidin-Sepharose beads. 13 has proven sufficiently cell permeable to rescue cells from apoptotic execution. These novel caspase inhibitors should provide powerful probes for the study of the active caspase proteome during apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Apoptosis is a highly conserved process by which eukaryotic cells commit suicide.1,2 This form of programmed cell death involves a reproducible series of cellular changes that include cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, membrane blebbing and, in most cases, DNA fragmentation. Studies performed over the past decade have revealed that many of the changes observed in apoptotic cells result from the action of a family of cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases termed caspases.3–5 The caspase family can be divided into two distinct subfamilies, the cytokine activators (caspases 1, 4, 5, 11 and 12) and those involved in apoptosis. Apoptotic caspases can be further subdivided into initiator caspases (caspases 2, 8, 9 and 10), which transduce an apoptotic signal into proteolytic activity, and effector caspases (caspases 3, 6 and 7), which are activated by initiator caspases and are in turn responsible for the cleavage of the majority of the substrates leading to the demise of the cell.3–5

Previous studies have demonstrated that the various caspases differ in their substrate specificies.4,6 While all cleave on the carboxyl side of aspartate residues, caspases 3 and 7 prefer acidic residues in the P4 position of the substrate, whereas caspases 1, 4, 5, 6 and 8–10 prefer aromatic or hydrophobic residues in this position.7 These substrate specificities have been explained, at least in part, by differences in the corresponding S4 substrate binding pockets of the various caspase family members as crystal structures have become available.8–13

Earlier progress in understanding the role of caspases in apoptosis was critically dependent on the availability of caspase inhibitors and affinity labels. After the demonstration that apoptotic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP1)14,15 occurs at the sequence asp-glu-val-asp↓gly,16 an observation that implicated caspases in apoptotic cleavage, the availability of the peptide caspase 1 inhibitor tyr-val-ala-asp-chloromethylketone (YVAD-cmk)a allowed demonstration of the critical role of this class of enzymes in apoptotic events.16 Moreover, biotinylated derivatives of YVAD-cmk and of benzyloxycarbonyl-glu-lys-asp-acyloxymethylketone (Z-EKD-aomk), an inhibitor designed with apoptotic effector cleavage sequences in mind,17 were successfully utilized to identify multiple species of caspases 3 and 6 as the predominant active caspases in apoptotic cells17,18 despite the fact that the YVAD and EVD peptide sequences were subsequently shown to bind caspase 1 more avidly than caspases 3, 6 and 7.19,20 This ability of covalent caspase inhibitors to derivatize apoptotic caspases despite less than optimal affinity of their peptide moieties for the enzyme active sites has been attributed to the high concentrations and prolonged incubation times often utilized in biological experiments.19

Although the previous chloromethylketone (cmk) and acyloxymethylketone (aomk) affinity labels have proven useful for affinity labeling of cell-free extracts prepared from apoptotic cells, these reagents also had several limitations. First, because of the short arm linking biotin to the label, they were difficult to use for affinity purification of caspases. Instead, because the biotin did not extend far beyond the active site cleft of the enzymes, the earlier affinity labels were most useful for detection on blots after polypeptides were denatured. Second, because biotin was used as a tag, endogenous biotinylated polypeptides were also detected on blots. Third, the previous affinity labels penetrated cells poorly and were generally used to label caspases under cell-free conditions,17,18,21–23 although it has been reported that caspases in intact cells can sometimes be labeled when cells are subjected to prolonged incubations with these compounds prior to introduction of an apoptotic stimulus.24,25

In view of the large number of caspase species that can be detected when samples of affinity labeled caspases are separated by charge and size on two-dimensional polyacrylamide gels,17,18,21 it is clear that further work is required to fully characterize the posttranslational modifications that regulate caspase activation and activity. Here we describe the synthesis and initial characterization of several novel irreversible acyloxymethylketone caspase inhibitors labeled with biotin 12a–d or 2,4-dinitrophenyl (DNP) 13 that overcome some of the limitations of earlier inhibitors. The construction of affinity probes in which the biotin was coupled via an extended linker arm enabled the affinity purification of nondenatured enzyme from cell-free extracts prepared from apoptotic cells overexpressing caspase-6 fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). The probe 13 labeled with DNP, rather than biotin, not only displayed much lower background labeling of polypeptides in cell-free extracts, but also penetrated cells and efficiently inhibited apoptosis in situ.

CHEMISTRY

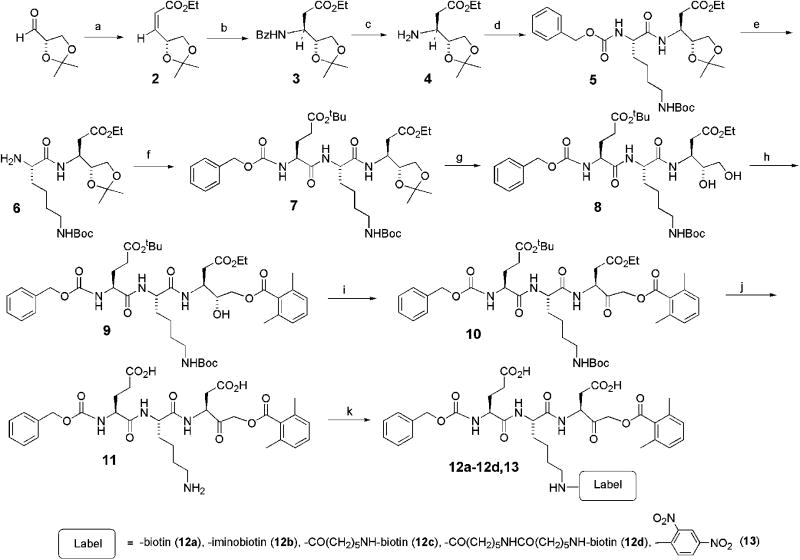

To provide an affinity label that could be readily tagged with various moieties, the peptidyl acyloxymethylketone inhibitor Z-EKD-aomk (11) was synthesized as shown in Scheme 1. D-glyceraldehyde acetonide 1 was prepared from D-mannitol.26 Wittig reaction of the chiral acetonide with Ph3P=CHCO2CH2CH3 in methanol at 0°C gave a separable isomeric mixture (Z/E, 8:1) of the α,β-unsaturated esters 2.27 Reaction of the mixture of esters with benzylamine in the absence of solvent at −50°C for 2 days afforded the (3R)-benzylamino ester 3. Removal of the Z protecting group by hydrogenation furnished the amine 4, which was coupled with N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-N-ε-butoxycarbonyl-lysine-succinyl ester to give the dipeptide 5. Hydrogenation of 5 afforded amine 6, which was coupled with N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-γ-O-tert-butyl-glutamyl-succinyl ester to give the protected tripeptide analog 7. Selective acid hydrolysis of the acetonide group of 7 to give the diol 8, without partial removal of the tbutyl protecting groups, could not be achieved even under relatively mild solution conditions28 but was effected in good yield by treatment with Montmorillonite K10 in aqueous ethanol. Esterification of the primary hydroxyl of 8 with 2,6-dimethylbenzoyl chloride in pyridine/dimethylaminopyridine/DMPU at room temperature produced the ester 9. Attempts to effect oxidation of the sterically-crowded secondary alcohol group of 9 with a variety of mild oxidizing reagents proved unsuccessful. However, oxidation under Dess-Martin conditions29 afforded the ketone 10 in virtually quantitative yield. Finally, cleavage of the protecting groups of the glutamyl, lysyl and ‘aspartyl analog’ moieties of 10 was achieved with TFA containing a catalytic amount of water to give the desired Z-EKD-aomk 11. A series of biotin-labelled derivatives of 11 (compounds 12a–12d) was then prepared by reaction of the free ε-amino group of lysine with the N-hydroxysuccinamides of biotin, iminobiotin, 6-[biotinamido]hexanoate (LC biotin) and 6-[biotinamido]-6-hexanamidohexanoate (LCLC biotin). These have ‘spacer arms’ between the Nε-lysine of the inhibitor and the avidin-binding ureido ring nucleus of biotin of ~13.5, 13.5, 22.5 and 30.0 Å, respectively. The N-ε-2,4-dinitrophenyl affinity probe 13 was prepared by reaction of 11 with 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of caspase inhibitors.

a) Ph3P=CHCO2CH2CH3, MeOH, 0°C. b) Benzylamine, −50°C, 48 h. c) H2, Pd/C, EtOH. d) Z-Lys(Boc) N-hydroxysuccinimide, CH2Cl2, 12 h. e) H2, Pd/C, EtOH. f) Z-Glu(OtBu) N-hydroxysuccinimide, CH2Cl2, 12 h. g) Montmorillonite, EtOH/H2O (5:1), 75°C, 3 h. h) 2,6-dimethylbenzoylchloride, pyridine, DMAP, DMPU, 48 h. i) Dess-Martin periodate, 0°C to rt., 4 h. j) 95% TFA/H2O, 12 h. k) labelling reagent, water, 12 h.

RESULTS

Synthesis of novel caspase inhibitors

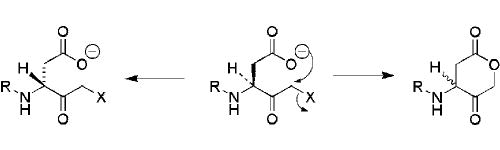

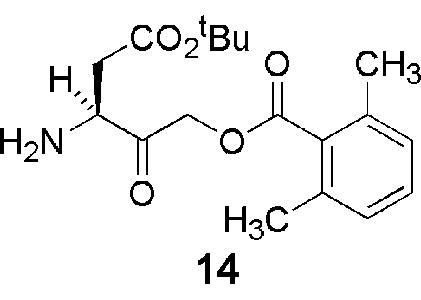

Peptidyl halo- and acyloxymethylketone inhibitors of caspases are notoriously difficult to prepare; and a number of commercially available preparations of these compounds exhibited variable chemical composition and biological activity upon testing in our laboratory. This variability appears to reflect, at least in part, instability of the 3-aminoacyl-4-oxopentanoic acid (‘aspartyl’) unit substituted with a good leaving group in the 5 position, which undergoes a number of reactions, including epimerization and facile cyclization to the corresponding γ-lactone, during chemical syntheses (Fig. 1). Accordingly, initial attempts to employ a linear synthetic strategy to the target compound 11 via the protected acyloxymethylketone 14 proved unsuccessful. While this intermediate was accessible, albeit in modest yield, by a classical diazomethylketone route from Z-aspartic acid,30 the inherent instability of the acyloxymethylketone group gave rise to significant problems during the subsequent coupling and deprotection steps in the synthesis. As a result, we elected to use a new synthetic approach in which the ‘aspartyl’ acyloxymethylketone subunit of the molecule is created only after the peptide bond forming steps of the synthesis are complete. Using this strategy, the tagged inhibitors 12a–d and 13 could all be prepared in >95% purity.

Figure 1. Epimerization and cyclization of ‘aspartyl’ halo- and acyloxy- methylketone analogs.

R = H or acyl, X = halogen or acyloxy.

The novel probes inhibit caspases 1–8

Synthetic colorimetric substrates containing a cleavage sequence similar or identical to the preferred tetrapeptide recognition sequence of each caspase are commercially available to measure enzyme activity. Using standard spectrophotometric methods, kinetic parameters for the cleavage of these substrates catalyzed by caspases 1–8 were determined (Table 1). The vmax and Km values for the p-nitroaniline (pNA) substrates are in good agreement with those reported previously.19,31,32 Assays of caspases 9 and 10 yielded Km values that were outside the range of substrate concentrations tested and are not further considered here.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters determined for human caspases 1–8 reacted with LC biotin-derivatized inhibitor 12c

| Caspase | Substrate | Vmax (pmol/min) | Km (μM) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | YVAD-pNA | 110 | 100 | 0.0063 |

| 2 | LEHD-pNA | 400 | 560 | 29 |

| 3 | DEVD-pNA | 110 | 74 | 0.84 |

| 4 | LEHD-pNA | 510 | 1100 | NT |

| 5 | LEHD-pNA | 610 | 2500 | NT |

| 6 | VEID-pNA | 230 | 220 | 550 |

| 7 | DEVD-pNA | 530 | 230 | 1.2 |

| 8 | IETD-pNA | 130 | 140 | 0.54 |

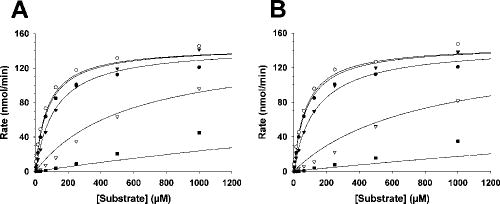

The inhibition constants (Ki) for 12c when added to caspases 1–8 were evaluated using steady state kinetic methods under the assumption of a slow, tight binding inhibitor (Table 1). 12c inhibited all tested caspases (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Consistent with a previous observation showing that removal of the N-terminal aspartate from the DEVD sequence diminishes the affinity for caspases 3 and 7 much more dramatically than for caspases 1 and 4,19 12c had a lower Ki for caspase 1 than for caspases 3, 7 and 8. Nonetheless, submicromolar to low micromolar values for were calculated for the Ki for these apoptotic caspases (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). As was the case with covalent inhibitors based on YVAD or Z-VAD,20 12c was not particularly potent at inhibiting caspase 6, with a calculated Ki of 550 μM. 12a, 12b, 12d and 13 were confirmed to have similar potencies by steady state kinetics with caspase-3 (Table 2 and Fig. 2B). The similar potencies of these various derivatives are consistent with previous reports that the P2 sidechain of substrate analogues points away from the caspase active site, permitting extensive derivatization at this site without altering affinity for the enzyme.10,33

Figure 2. Michaelis-Menton graphs of caspase 3-catalyzed Ac-gDEVD-pNA cleavage in the absence and presence of peptidyl aomk inhibitors.

A) Biotinylated inhibitor 12a, B) DNP labelled inhibitor 13. Inhibitor concentrations: closed circle, 0 μM; open circle, 0.1 μM; inverted closed triangle, 1.0 μM; inverted open triangle, 10 μM; closed square, 100 μM.

Table 2.

Inhibition of Caspase 3 by Substituted Peptidyl aomk Inhibitors

| Label on Nε-lysine of 11 | Vmax (pmol/min) | Km (μM) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| βbiotin, 12a | 140 | 72 | 1.4 |

| −iminobiotin, 12b | 140 | 70 | 1.5 |

| 6-[biotinamido]hexanoate (LC-biotin), 12c | 140 | 52 | 0.79 |

| 6-[biotinamido]-6-hexanamidohexanoate (LCLC-biotin), 12d | 150 | 79 | 1.1 |

| DNP, 13 | 150 | 75 | 1.0 |

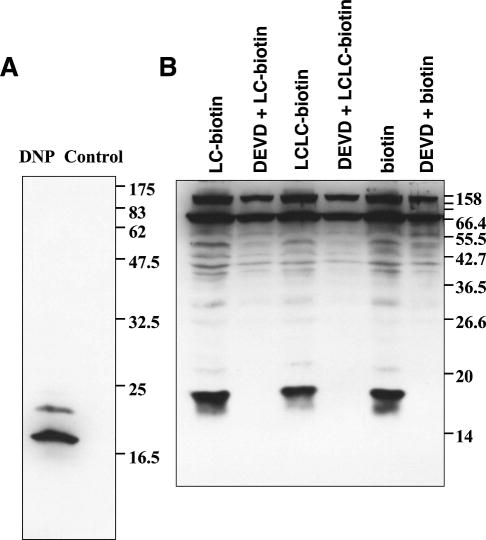

The novel inhibitors detect active caspases on blots

Blotting with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) –coupled streptavidin was used to evaluate the ability of the synthesized inhibitors to affinity label active caspases in extracts from apoptotic Jurkat cells. In this way it was shown that all derivatized inhibitors are able to bind covalently to active caspases in vitro (Fig. 3A, B). Pretreatment of extracts with the commercially available caspase inhibitor DEVD-aomk as a control abolished the labelling by the inhibitors, thus confirming the detected bands to be active caspases labelled with the various affinity probes.

Figure 3. Use of new affinity labels for blotting.

After preincubation with diluent or DEVD-aomk, apoptotic cell lysates were reacted with the DNP labeled caspase probe 13 (A) or biotinylated probe 12c (B), subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with anti-DNP antibody (A) or HRP-coupled streptavidin (B).

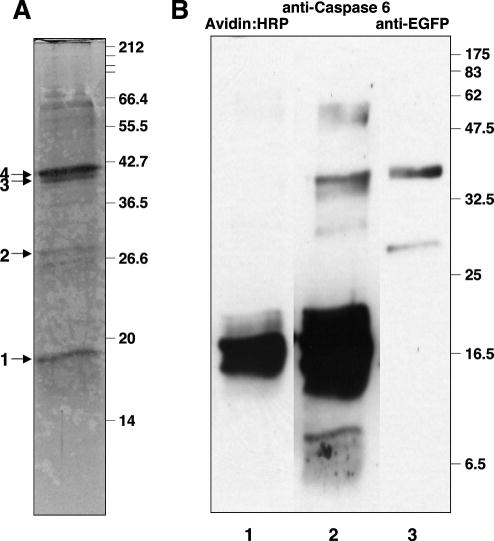

Affinity purification of native caspase 6 using the novel inhibitors

One potential use of inhibitors 12c, 12d and 13 is as affinity tags to allow purification from cell extracts of sufficient quantities of caspases for further studies (e.g., the analysis of posttranslational modifications). This use is illustrated for 12c, which was employed to purify caspase 6-EGFP from apoptotic DT40 chicken lymphoma cells that were engineered as previously described34 to overexpress a chicken procaspase 6-EGFP fusion protein (Fig. 4). To avoid the copurification of endogenous biotinylated proteins, apoptotic extracts were first passed over an avidin column to remove the bulk of endogenous biotinylated polypeptides. Extracts were then reacted with the biotinylated probe 12c, dialyzed to remove excess probe, and passed over monomeric avidin, which bound the affinity-labeled caspases. After a series of increasingly stringent washes, caspases were eluted with D-biotin as a highly enriched fraction, subjected to sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAG)E and stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 4A). This test-of-concept experiment was performed on cells that overexpressed caspase 6 with the idea that successful recovery of EGFP-caspase 6, which has a somewhat low affinity for the inhibitor (Table 1), would indicate its potential usefulness with other caspases in the future.

Figure 4. Affinity purification of caspase 6-EGFP fusion protein from cell extracts.

(A) SDS-PAGE gel stained with Colloidal Coomassie Blue showing the fraction eluted with biotin. (B) Immunoblot characterization of the biotin eluted fraction. After SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and reacted with: lane 1, streptavidin-HRP; lane 2, anti-chicken caspase-6; and lane 3, anti-EGFP antibody. The blot was subjected to a stripping procedure44 between detection reagents.

The affinity purified caspase fraction contained four major bands with estimated molecular weights of 18, 28, 42.5 and 44 kDa (Fig. 4A). In order to identify these, a duplicate SDS-polyacrylamide gel was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, probed with HRP-coupled streptavidin, stripped, probed with rabbit anti-chicken caspase-6 antiserum, stripped again and probed with anti-EGFP antiserum (Fig. 4B). Band 1 bound HRP-streptavidin very strongly. Bands 1, 3 and 4 were also recognized by anti-chicken caspase-6, whereas bands 2 and 4 were recognized by anti-EGFP. These results suggested that band 1 corresponded to the large subunit of caspase 6, band 2 to EGFP, and bands 3 and 4 to the EGFP-caspase 6 fusion species. To verify this identification, bands were excised, digested with trypsin and subjected to Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization- Time of Flight (MALD-ToF) mass spectrometry. Results of this analysis confirmed the band identifications deduced by immunoblotting (Table 3). Thus, this experiment demonstrates the utility of this affinity label for the isolation of caspases from cell extracts under nondenaturing conditions.

Table 3.

Identification of polypeptides in biotin eluted fraction by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry

| Band # | App. Mwa | Protein ID | GenBank # | Mw | Mw total | MOWSEb | Cover(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 kDa | Caspase 6 | AF469049 | 18167 | 4.11E+04 | 46 | |

| 2 | 28 kDa | GFP | P42212 | 26887 | 5.38E+08 | 49 | |

| 3 | 38 kDa | Caspase 6 | AF469049 | 18167 | 45053 | 1.79E+03 | 17 |

| GFP | P42212 | 26887 | 1.52E+07 | 45 | |||

| 4 | 40 kDa | Caspase 6 | AF469049 | 18167 | 45053 | 2.54E+04 | 22 |

| GFP | P42212 | 26887 | 1.52E+07 | 45 |

Apparent masses based on the SDS preparative gel from which the band was excised.

Molecular weight search s(MOWSE) scores calculated according to the method of Pappin et al. 48 using the MS-Fit tool.

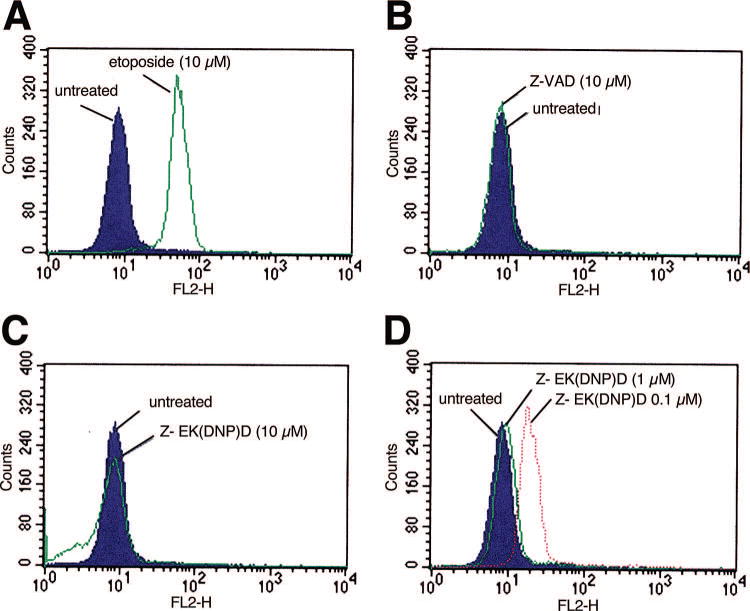

A DNP-derivatized probe is a potent inhibitor of apoptosis in intact cells

Although Z-VAD(OMe)-fmk and Z-EK(biotin)D-aomk 12a have a similar mode of action, i.e., reaction with the sulfhydryl group of the active site cysteine, Z-VAD(OMe)-fmk is sufficiently lipophilic to cross the plasma membrane and inhibit caspases in situ, whereas the more polar Z-EK(biotin)D-aomk is not cell-permeable. We hypothesized that the substitution of an aromatic DNP group for biotin to yield 13 might increase the lipophilicity of this class of inhibitors, thus facilitating passage through the plasma membrane and inhibition of apoptosis in intact cells. To address this possibility, we treated Jurkat cells with etoposide (10 μM) for 5 h in the presence or absence of varying concentrations of 13. Apoptotic cells were detected by TUNEL labeling and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 5). As a control, the level of apoptosis inhibition was compared to that achieved with cell permeable Z-VAD(OMe)-fmk (10 μM). 13 at 1 μM and 10 μM was found to essentially abolish apoptosis in etoposide-treated Jurkat cells. These data demonstrate that 13 is a cell permeable inhibitor of caspases and apoptosis in human cells.

Figure 5. 13 rescues Jurkat cells from apoptosis induced by etoposide.

Jurkat cells were treated with etoposide with or without 13 as indicated for 5 h. Cells were then stained with TUNEL reagent and analyzed by flow cytometry to assess the level of cell death. A total of 20,000 events were analyzed for each curve.

DISCUSSION

The human genome encodes at least eleven different caspase gene products, but many more active caspase species are detected when apoptotic cell lysates are incubated with affinity probes such as 12a or biofinylated YVAD-cmk and fractionated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.17,18 In fact, this active caspase proteome may comprise 30 or more species in certain cell types.35 In two studies where caspases were labeled, it was shown that many of the spots in the two-dimensional gels were derived from caspases-3 and −6, but other spots remained unidentified.17,18 Many of these different active caspase species are likely to result from differential processing of the proenzymes, phosphorylation,35–37 nitrosylation38–41 and possibly other post-translational modifications. In order to characterize these modifications, it will be important to be able to purify caspases away from more abundant cellular polypeptides.

One approach to this is the isolation of caspases tagged at their C-termini with peptide tags. This has two potential drawbacks, however. First, unlike affinity labeling, such methods do not distinguish between active caspases and their procaspase precursors. Second, there is the possibility that tagging will alter the posttranslational modifications. We have observed, for example, that tagged caspase-7 no longer exhibits a prominent posttranslational modification that is present in the wild-type enzyme (N. Korfali, X.W. Meng, WCE and SHK, unpublished). These considerations prompted development of additional caspase affinity labeling reagents.

In developing these new agents, we have attempted to address some of the deficiencies of previous reagents. Several of the previously available caspase affinity labeling reagents have proven difficult to use during affinity purification. For example, caspases affinity labeled with 12a quantitatively flow through avidin- and streptavidin-agarose columns under nondenaturating conditions (F. Durrieu and WCE, unpublished observations), apparently because the covalently bound inhibitor occupies a deep pocket shielded by a “flap” of protein that blocks access to the biotin residue.10,33 In fact, affinity purification of the large subunits of active caspases was possible with 12a if the labeled enzymes were first denatured in hot SDS prior to passage over the affinity column (F. Durrieu and WCE, unpublished observations), suggesting that efficient purification of native caspases might be possible with a new generation of inhibitor in which the biotin was linked to the P2 lysine residue by an extended linker arm.

We were also aware that the repertoire of caspase affinity labeling reagents was limited, at least in part, by fact that synthesis of peptide acyloxymethyl ketone inhibitors is challenging. The synthetic route described here provides a convenient approach for the preparation of a new generation of irreversible caspase inhibitors to which a variety of affinity tags can be attached. This route not only results in a relatively high yield, but also avoids the cyclization reaction between the aspartate sidechain and the acyloxymethylketone moiety that have plagued previous syntheses. As a result, purity of the inhibitors prepared by this route is >95%.

This synthetic route provided a suitable opportunity to ask whether biotinylated inhibitors with longer aliphatic arms linking the biotin could be useful for the affinity purification of caspases under nondenaturing conditions. Accordingly, we synthesized the acyloxymethylketone inhibitor Z-EKD-aomk in which the ε-amino group of the lysine residue was linked to biotin by spacers of 13.5, 22.5 and 30 Å (12a–d). As predicted from the fact that the P2 residue extends away from the enzyme active site, the recognition of these affinity probes by caspases did not appear to be influenced by the length of the linker arm (Table 2).

The present inhibitors were based on the Z-EKD peptide sequence previously shown to allow derivatization of caspases 3 and 6 in apoptotic extracts.17 These new inhibitors displayed a range of affinity constants (Table 1) similar to that previously reported for EVD-based inhibitors,19 with high affinity for caspase 1, intermediate affinity for caspases 3, 7 and 8, and somewhat lower affinity for caspase 6. These differences reflect differences in geometry and chemical composition at the S3 and S4 subsites of the various enzymes.8–12 The present compounds were not designed to alter this spectrum of affinities, but to instead test the hypothesis that extended linkers between the lysine moiety and biotin would allow affinity purification under nondenaturing conditions and that substitution of the hydrophobic DNP moiety would allow penetration of intact cells in sufficient concentrations to inhibit apoptosis.

As expected based on our prior unpublished results, when we synthesized Z-EKD-aomk and linked biotin directly to the ε-amino group of the lysine, the resulting 12a efficiently labeled active caspases as detected in immunoblots, but these enzymes failed to bind avidin under native conditions. In contrast, caspases bound to inhibitor 12c, in which the biotin was linked to the ε-amino group of the lysine by a longer linker arm, could bind to avidin under native conditions. As proof of principle, we successfully used 12c to purify nondenatured EGFP-caspase-6 from cell-free apoptotic extracts on monomeric avidin. This protocol allowed us to wash the beads relatively stringently but elute the bound enzyme under mild conditions with D-biotin. Characterization of the purified fraction by both immunoblotting and MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry confirmed the presence of active caspase-6 as a major constituent of the fraction. Even though the affinity of the peptide moiety for caspase 6 was less then optimal (Table 1), prolonged incubation at micromolar concentrations was able to overcome this obstacle, as had been previously reported for other covalent caspase inhibitors.19 Accordingly, we expect that 12c will also be useful for purification of caspases for which it has higher affinity. Thus, this reagent should prove useful in future studies aimed at characterization of the active caspase proteome by affinity purification of labeled caspases from apoptotic cytosolic extracts and identification of the relevant polypeptides and their post-translational modifications by mass-spectrometric analysis. In addition, because denaturation is not required, this reagent should be useful for purifying polypeptides that are associated with active caspases.

Another problem with characterization of the active caspase proteome is that the previously described affinity-labeling agents were poorly cell permeable and were generally utilized in cell-free extracts.17,18,21,23 Because effector caspases are activated both by themselves and by initiator caspases, this raises the possibility that some of the active species observed by this technique might have been activated only following cell homogenization, when inactive caspases sequestered in various subcellular compartments would be exposed to active caspases from other compartments. In Jurkat cells that had been exposed to etoposide, striking inhibition of the onset of apoptosis was observed with 13. Therefore, substitution of the DNP moiety for biotin (12a–d) appears to enable 13 to cross the plasma membrane, where it can then inhibit cytosolic caspases and blunt the apoptotic response. This means that 13 can be used to label active caspases in situ, thereby avoiding concerns about caspase activation during cell lysis. Compared to biotinylated VAD-fmk, which has also recently been utilized for this purpose,24,25 13 has the advantage of not requiring preloading prior to administration of an apoptotic stimulus. Moreover, 13 lacks a biotin moiety, thereby diminishing contamination of any pull-downs by endogenous biotinylated proteins,17,25 and instead contains the widely studied hapten DNP, for which immunological reagents are commercially available.

In conclusion, the reagents described here comprise a new generation of small-molecule caspase inhibitors that can be used for experiments aimed to characterize the active caspase proteome in apoptotic cells. Identification of the members of this proteome will be an important step toward understanding the global regulation of the apoptotic response by protein kinases, phosphatases and other enzyme modification systems in different normal and transformed cell populations, in response to different stimuli, and when the apoptotic cascade is modulated by the simultaneous up- or down-regulation of other cytosolic signaling cascades.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry

Reagents were obtained from the following suppliers: D-mannitol, Ph3P=CHCO2CH2CH3, benzylamine, palladium on charcoal, montmorillonite K10, 2,6-dimethylbenzoyl chloride, pyridine, dimethylaminopyridine, 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone, Dess-Martin periodinane, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK); N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-N-ε-butoxycarbonyl-lysine-succinyl ester and N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-γ-O-tert-butyl-glutamyl-succinyl ester from Bachem AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland); biotin-NHS, iminobiotin-NHS, LC-biotin-NHS and LC-LC-biotin-NHS from Pierce (Rockford, IL). In synthetic procedures, flash column chromatography was carried out over silica 60 (230–400 mesh), analytical thin layer chromatography was carried out on 0.25 mm silica gel plates (Fisher, Loughborough, UK) and organic extracts were routinely dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo. Purifications were carried out using a Waters 600 HPLC (Milford, MA) coupled to a Waters 486 detector. A Lichrosorb 100 RP-8 column (7 x 250 mm, 5 μm) was used for preparative HPLC (Jones Chromatography, Hengoed, UK).

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on Varian Gemini 200 (Palo Alto, CA) and Bruker AC 250, 360 or 600 spectrometers (Karlsruhe, Germany). Fast Atom Bombardment (FAB) mass spectra were recorded on a Kratos MS 50 TC (Manchester, UK) instrument. HPLC-MS analysis was accomplished by electrospray ionization (EI) and analysis on a MicroMass platform II spectrometer (Manchester, UK) after separation on a Waters Alliance 2795 HPLC using a 10 μm C-18 column (1 x 150 mm) eluted isocratically with AcCN:H2O:HCOOH (2:98:0.1) for 2 min followed by a gradient to 60% AcCN:H2O:HCOOH (97:3:0.05) over 20 min (flow rate of 1 ml/min). [(1R)-1-[(4S)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl]-2-carboxyethyl]ethylamine (4). (4R) -(2) (400.5 mg, 2.0 mmole), prepared from D-glyceraldehyde acetonide by the procedure of Matsunaga et al.,27 was stirred with benzylamine (437 μl, 429 mg, 4.0 mmole) at −50ºC for 48 h in the absence of solvent. The reaction mixture was dissolved in EtOAc (25 ml), washed with water, dried, and concentrated. Flash column chromatography eluting with EtOAc:hexane (20:1) afforded N-Benzyl-[(1R)-1-[(4S)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl]-2-carboxyethyl]ethylamine (3, 460 mg, 75%) as a colorless oil. Rf (5% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.70; MS (FAB, thioglycerol) m/z 308.1859 (MH+, C17H26NO4 requires 308.1862); 1H-NMR (CDCl3): 1.24 (t, 3H, CH2CH3), 1.35 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.36 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.82 (br. s, 1H, NH), 2.46 (m, 2H, CH2CO2Et, 3.13 (q, 1H NCH), 3.81 (t, 2H, OCH2CH3), 4.00 (m, 2H, CH2Ar), 4.12 (m, 3H, CHO + CH2O) and 7.30 (m, 5H, Ar); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 13.4 (OCH2CH3), 24.4 (CH3), 25.7 (CH3), 35.4 (CH2CO2Et), 50.7 (NCH), 55.1 (CH2Ar), 59.8 (OCH2CH3), 65.5 (CH2OC), 75.8 (CHOC), 108.5 (-OCO-), 126.3, 127.5, 127.7 and 139.7 (ArC) and 171.4 (CO2Et).

Hydrogenation of 3 (460 mg, 1.50 mmole) over 10% Pd/C in anhydrous EtOH (25 ml) under atmospheric pressure for 12 h, removal of the catalyst by filtration and purification by flash column chromatography eluting with 1–10% acetone/CH2Cl2 gradient afforded 4 (279 mg, 86%) as a colorless oil. Rf (5% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.25; Found: C 54.79%, H 8.94%, N 6.34% (calc for C10H19NO4: C 55.28%, H 8.81%, N 6.45%); MS (FAB, NOBA) m/z 218.1393 (MH+, C10H20NO4 requires 218.1392); 1H-NMR (CDCl3): 1.19 (t, 3H, OCH2CH3), 1.27 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.35 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.02 (s, 2H, NH2, 2.33 (m, 2H, CH2CO2Et), 3.13 (m, 1H, NCH), 3.68 (m, 1H, CHO), 3.99 (m, 2H, OCH2CH3) and 4.08 (m, 2H, CH2O);13C-NMR (CDCl3): 12.9 (OCH2CH3), 24.3, 25.5 (2xCH3), 37.6 (CH2CO2Et), 49.2 (CHN), 59.3 (OCH2CH3), 65.0 (CH2OC), 75.6 (CHOC), 108.0 (-OCO-), 170.6 (CO2)

N-[N-((R)-Nα-Benzyloxycarbonyl-Oγ-tert-butyl-glutamyl)-(R)-Nε-tert-butoxycarbonyllysyl]-[(1R)-1-[(4S)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl]-2-carboxyethyl]ethylamine (7)

A solution of 4 (279 mg, 1.28 mmole) in 2 ml dry CH2Cl2 was added to a solution of (R) N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-N-ε-tert-butoxycarbonyl-lysine N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (673 mg, 1.41 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (10 ml) and the mixture stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 ml), washed with H2O (10 ml), dried and concentrated. Column chromatography using 0–10% acetone in CH2Cl2 as eluent afforded N-[(R)-Nα-benzyloxycarbonyl-Nε-tert-butoxycarbonyl-lysyl]-[(1R)-1-[(4S)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl]-2-carboxyethyl]ethylamine (5, 632 mg, 85%) as a colorless oil. Rf (5% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.45; MS (FAB, NOBA) m/z 580.3234 (MH+, C29H46N3O9 requires 580.3235); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 13.3 (OCH2CH3), 21.7 (Kγ-CH2), 24.0 (Kβ-CH2), 25.4 (2 x CH3), 27.7 (tBu-CH3), 28.9 (Kδ-CH2), 36.1 (CH2CO2Et), 35.9 (Kε-CH2), 45.9, 54.5 (2xCHN), 60.1 (OCH2CH3), 65.2 (CH2OC), 66.2 (C(CH2)3), 75.5 (CHOC), 78.2 (CH2Ph), 108.6 (-OCO-), 127.4, 127.8, 135.7 (ArC), 155.6 (CONH), 170.3 and 171.4 (2xCO2). Hydrogenation of 5 (630 mg, 1.09 mmole) with H2 over 10% Pd/C in anhydrous EtOH (25 ml) under atmospheric pressure for 3–4 h gave the crude amine after filtration and concentration. Column chromatography eluting with a 1–10% acetone/CH2Cl2 gradient gave N-[(R)-Nε-tert-butoxycarbonyl-lysyl]-[(1R)-1-[(4S)-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl]-2-carboxyethyl]ethylamine (6, 446 mg, 92%) as a colorless oil. Rf (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.55; MS (FAB, NOBA) m/z 446.2866 (MH+, C21H40N3O7 requires 446.2866); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 13.3 (OCH2CH3), 21.7 (Kγ-C H2), 24.0 (Kβ-CH2), 25.4 (2 x CH3), 27.6 (tBu-CH3), 28.8 (Kδ-CH2), 36.1 (CH2CO2Et), 39.2 (Kε-CH2), 45.9 (CHN), 53.9 (CHN), 59.8 (OCH2CH3), 65.2 (CH2OC), 75.4 (CHOC), 77.8 (CH2Ph), 108.5 (-OCO-), 155.4 (CONH), 170.2 and 173.3 (2 x C O2). To a solution of N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-γ-O-tert-butyl-glutamyl N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (478 g, 1.1 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (10 ml), 6 (440 mg, 0.99 mmole) was added and the mixture stirred overnight under dry N2 at room temperature. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 ml) washed with H2O, dried, and concentrated. Column chromatography using a 0–20% acetone/CH2Cl2 gradient afforded 7 (620 mg, 81%) as a colorless amorphous solid (mp 62–63°C). Rf (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.60; Found: C 59.28%, H 7.93%, N 7.32% (calc for C38H60N4O12: C 59.67%, H 7.91%, N 7.09%); MS (FAB, NOBA) m/z 765.4286 (MH+, C38H61N4O12 requires 765.4285); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 13.9 (OCH2CH3), 22.3 (Kγ-CH2), 24,2, 25.8 (2 x CH3), 27.3 (tBu-CH3), 27.9 (tBu-CH3), 28.3, 29.1, 29.2(3 x CH2), 36.5 (CH2CO2Et), 39.9 (Kε-CH2), 48.2, 53.1, 54.6 (3 x CHN), 60.6 (OCH2CH3), 65.9 (CH2OC), 66.9 (OC(CH3)3), 75.7 (CHOC), 80.9 (CH2Ph), 107.9 (-OCO-), 120.5-136.0 (ArC), 155.9, 156.0 (2 x CONH), 170.7 , 170.9, 171.2 and 172.6 (4 x CO2)

N-[N-((R)-Nα-Benzyloxycarbonyl-Oγ-tert-butyl-glutamyl)-(R)-Nε-tert-butoxycarbonyl-lysyl]-(1R,2R)-1-(carboxyethylmethyl)-2,3-dihydroxypropylamine (8)

A solution of 7 (100 mg, 0.13 mmole) in EtOH:H2O (5:1, 10 ml) was stirred with Montmorillonite K10 at 75ºC for 3 h. The suspension was diluted with EtOAc (20 ml), filtered through Celite, washed with H2O, dried, and concentrated. Flash column chromatography eluting with 0–50% acetone/CH2Cl2 yielded 8 (66 mg, 70%) as a colorless oil. Rf (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.55; Found: C 55.38%, H 7.79%, N 7.30% (calc for C35H56N4O12.2H2O: C 55.25%, H 7.95%, N 7.36%); MS (FAB, NOBA) m/z 725.3987 (MH+, C35H57N4O12 requires 725.3974); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 13.4 (OCH2CH3), 21.9 (KγCH2), 27.3 (tBu-CH3), 27.7 (tBu-CH3), 28.6 (2 x CH2, Eβ and Kβ), 30.9 (Eγ-CH2), 33.9 (Kδ-CH2), 35.9 (CH2CO2Et), 39.7 (Kε-CH2), 47.1, 52.8, 53.9 (3xCHN), 60.6 (OCH2CH3), 62.5 (CH2OH), 66.4 (OC(CH3)3), 72.2 (CHOH), 80.4 (CH2Ph), 127.4, 127.8, 135.6 (ArC), 155.9 (2 x CONH), 170.9, 171.8, 172.1 and 172.5 (4 x CO2)

3-[N-((R)-Nα-Benzyloxycarbonyl-glutamyl)-(R)-lysyl]amino-(3R)-5-(2,6-dimethylbenzoyl)-4-oxopentanoic acid (Z-EKD-aomk,11)

To a stirring solution of DMAP (22 mg, 0.18 mmole), DMPU (23 mg, 21 μl, 0.18 mmole) and 2,6-dimethylbenzoyl chloride (17 mg, 0.10 mmole) in dry pyridine (5 ml), 8 (66 mg, 91 μmole) was added and the solution was stirred under dry Ar at room temperature for 3 d. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 ml), washed with H2O, dried, and concentrated. Column chromatography eluting with a 0–20% acetone/CH2Cl2 gradient gave N-[N-((R)-Nα-Benzyloxycarbonyl-Oγ-tert-butyl-glutamyl)-(R)-Nε-tert-butoxycarbonyl-lysyl]-(1R,2R)-1-(carboxyethylmethyl)-2-hydroxy-3-(2,6-dimethylbenzoyl)propylamine (9, 56 mg, 72%) as a colorless oil. Rf (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.65; MS (FAB, thioglycerol) m/z 857.4547 (MH+, C44H65N4O13 requires 857.4548); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 13.9 (OCH2CH3), 19.2 (2 x ArCH3), 22.0 (Kγ-CH2), 27.3 (tBu), 27.7 (tBu), 28.7 (2 x CH2, Eβ and Kβ), 30.5 (Eγ-CH2), 31.1 (Kδ-CH2), 34.1 (CH2CO2Et), 39.9 (Kε-CH2), 51.6, 52.6, 54.3 (3 x CHN), 60.6 (OC H2CH 3), 66.3(CH2OCOAr), 66.5 (OC(CH3)3), 75.8 (CHOH), 80.6 (CH2Ph), 127.0–135.6 (ArC), 155.9, 156.0 (2 x CONH), 168.4, 171.3, 171.4, and 172.4 (4 x CO2). Dess-Martin periodinane (0.92 ml, 138 mg, 0.325 mmol) in CH2Cl2 was added drop-wise to a stirred solution of 9 (56 mg, 65 μmole) in dry CH2Cl2 under Ar and the reaction was allowed to stir overnight. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (10 ml), washed with H2O, dried, and concentrated. Column chromatography eluting with a 0–10% acetone/CH2Cl2 gradient gave N-[N-((R)-Nα-Benzyloxycarbonyl-Oγ-tert-butyl-glutamyl)-(R)-Nε-tert-butoxycarbonyl-lysyl]-(1R,2R)-1-(carboxyethylmethyl)-3-(2,6-dimethylbenzoyl)-2-oxopropylamine (10, 44 mg, 80%) as a colorless glass. Rf (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.65; MS (FAB, thioglycerol) m/z 855.4392 (MH+, C44H67N4O13 requires 855.4393); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 13.9 (OCH2CH3), 19.2 (2 x ArCH3), 22.0 (Kγ-CH2), 27.3 (tBu), 27.7 (tBu), 28.7 (2 x CH2, Eβ and Kβ), 30.5 (Eγ-CH2), 31.1 (Kδ-CH2), 34.1 (CH2CO2Et), 39.9 (Kε-CH2), 51.6, 52.6, 54.3 (3 x CHN), 60.6 (OCH2CH3), 66.3 (OC(CH3)3), 66.5 (OC(CH3)3), 75.8 (COCH2O), 80.6 (CH2Ph), 127.0–135.6 (ArC), 155.9, 156.0 (2 x CONH), 168.4, 171.3, 171.4, 172.4 (4 x CO2) and 199.9 (CO). TFA/water (95:5, 300 μl) was added drop-wise to a stirred solution of 10 (5.0 mg, 5.8 μmole) in CH2Cl2 (2 ml) at 0°C and the mixture allowed to come to room temperature. After 2 h the reaction mixture was filtered and concentrated in vacuo, affording essentially homogeneous 11 (3.1 mg, 80%) as a colorless residue. Rf (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.05; HPLC-MS Rt (MH+) 24.14 min (694); MS (FAB, NOBA) m/z 694.3189 (MHNa+, C33H43N4O11Na requires 694.2826); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 17.3 (2 x ArCH3), 21.2 (Kγ-CH2), 25.4 (2 x CH2, Eβ & Kβ) 26.9 (Eγ-CH2), 31.1 (Kδ-CH2), 32.9 (CH2CO 2), 37.9 (Kε-CH2), 51.6, 52.6, 54.3 (3 x CHN), 78.9 (COCH2O), 80.6 (CH2Ph), 126.1–135.4 (ArC), 156.1, 160.2 (2 x CONH), 168.5, 169.6, 172.0, 174.2 (4 x CO2) and 199.5 (CO)

N-Biotinylated Z-EKD-aomk derivatives (12a–d)

These compounds were prepared on a 4–5 mmolar scale in 70–80% yields by treatment of 11 with the N-hydroxysuccinamides of biotin, iminobiotin, LC biotin and LCLC biotin. Typically, to a stirred solution of 11 (3.1 mg, 4.6 μmole) in dry DMF (500 μl), biotin N-hydroxysuccinamide (1.0 mg, 5.1 μmole) was added. After 3 h the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 ml) and washed with H2O to remove unreacted reagent and by-products. Concentration in vacuo afforded 12a (2.9 mg, 75%) as a colorless glass that was further purified by HPLC on a RP-8 silica column using MeOH:H2O:TFA (66:33:0.1) as eluant.

12a

13C-NMR (CD3CN-H2O): 19.8 (2 x ArCH3), 23.6 (Kγ-CH2), 26.3 (biotin γ-CH2), 27.6 (Kβ-CH2), 28.9 (biotin β-CH2), 29.2 (biotin δ-CH2), 30.2 (Eβ-CH2), 31.0 (Kδ-CH2), 31.3 (CH2CO2), 35.4 (Eγ-CH2), 36.4 (Kε-CH2), 39.7 (biotin α-CH2), 40.8 (biotin C-5), 53.9, 54.5, 55.5 (3 x CHN), 56.2 (biotin C-2), 61.1 (biotin C-3), 62.3 (COCH2O), 62.9 (biotin C-4), 67.5 (COCH2O), 68.0 (CH2Ph), 128.6, 129.1, 129.5, 130.9, 133.5, 136.3, 137.5 (12 x ArC), 158.0 (CO), 165.5 (biotin ureido-C), 170.3, 172.2, 172.3, 174.0, 176.0, 176.8 (6 x CO) and 202.1 (ketone-CO).

12b

13C-NMR (CD3CN-H2O): 20.3 (2 x ArCH3), 23.7 (Kγ-CH2), 26.7 (biotin γ-CH2), 28.4 (Kβ-CH2), 29.1 (biotin β-CH2), 29.2 (biotin δ-CH2), 30.7 (Eβ-CH2), 31.9 (Kδ-CH2), 32.6 (CH2CO2), 35.9 (Eγ-CH2), 36.9 (Kε-CH2), 40.0 (biotin α-CH2), 40.7 (biotin C-5), 54.2, 54.4, 56.1 (3 x CHN), 56.6 (biotin C-2), 62.7 (biotin C-3), 64.0 (COCH2O), 64.8 (biotin C-4), 68.1 (COCH2O), 68.5 (CH2Ph), 129.1, 129.5, 129.9, 131.3, 134.2, 136.8, 138.0 (12 x ArC), 156.1, 158.0, 158.6, 170.3, 172.2, 172.3, 174.0, 176.1 (CO & C=N) and 202.1 (ketone CO).

12c

13C-NMR (CD3CN-H2O): 19.3 (2 x ArCH3), 23.0 (Kγ-CH2), 25.6, 25.8 (2 x linker CH2), 26.3 (biotin γ-CH2), 27.6 (Kβ-CH2), 28.3 (biotin β-CH2), 28.6 (biotin δCH2), 28.8 (linker CH2), 29.7 (Eβ-CH2), 30.8 (Kδ CH2), 31.6 (CH2CO2), 34.9 (Eγ-CH2), 36.0 (linker CH2CO), 36.1 (kε-CH2), 39.3 (linker CH2N), 39.9 (biotin α-CH2), 40.3 (biotin C-5), 53.3, 53.9, 55.3 (3 x CHN), 55.8 (biotin C-2), 60.5 (biotin C-3), 61.8 (COCH2O), 62.2 (biotin C-4), 67.1 (COCH2O), 67.5 (CH2PH), 128.1, 128.5, 130.0, 133.0, 135.7, 135.7, 137.0, 139.0 (12 x ArC), 157.5 (CO), 164.8 (biotin ureido-C), 169.7, 171.5, 171.6, 173.6, 173.7, 175.3, 175.4 (7 x CO) and 201.8 (ketone-CO).

12d

13C-NMR (CD3CN-H2O): 19.3 (2 x ArCH3), 23.0 (Kγ-CH2), 25.6, 25.8 (4 x linker CH2), 26.3 (biotin γ-CH2), 27.5 (Kβ-CH2), 28.3 (biotin β-CH2), 28.7 (biotin δ-CH2), 29.8 (2 x linker CH2), 29.6 (Eβ-CH2), 31.0 (Kδ-CH2), 31.4 (CH2CO2), 34.9 (Eγ-CH2), 36.0 (2 x linker CH2CO), 36.2 (Kε-CH2), 39.1, 39.3 (2 x linker CH2N), 39.9 (biotin α-CH2), 40.3 (biotin C-5), 53.3, 53.9, 55.3 (3 x CHN), 55.8 (biotin C-2), 60.5 (biotin C-3), 61.8 (COCH2O), 62.2 (biotin C-4), 67.1 (COCH2O), 67.5 (CH2Ph), 128.1, 128.5, 130.0, 130.3, 133.0, 135.8, 137.0, 139.0 (12 x ArC), 157.6 (CO), 164.9 (biotin ureido-C), 169.7, 171.6, 171.7, 173.6, 173.7, 175.4, 175.5 (7 x CO) and 201.8 (ketone-CO).

HPLC-MS (Rt, MH+): 12a (18.50 min, 897), 12b (18.34 min, 896), 12c (18.28 min, 1010), 12d (18.11 min, 1123). Because exact mass determinations could not easily be obtained for these compounds directly, they were derivatized as their ethyl esters by treatment with 3% HCl in EtOH for 1 h at 10°C. MS (FAB, thioglycerol) of the monoethyl esters of 12a–d gave exact masses within a deviation of 0.8 ppm of the calculated MH+ values (See Supporting Information).

N-(2,4-Dinitrophenyl) Z-EKD-aomk (13)

To a stirred solution of 11 (3.1 mg, 4.6 μmole) in dry DMF (500 μl), N-methylmorpholine (50 μg, 5 μmole) and 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (950 μg, 5.1 μmole) were added. After 12 h the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 ml), washed with H2O, dried, and concentrated to afford 13 (2.9 mg, 75%) as a colorless glass. Rf (10% MeOH/CH2Cl2) 0.55; HPLC-MS Rt (MH+) 20.41 min (837); MS (FAB, NOBA) m/z MH+ 837.3028 (MH+, C39H45N6O15 requires 837.2943); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): 19.1 (2 x ArCH3), 21.5 (Kγ-CH2), 22.4 (Kβ-CH2), 27.4 (Eβ-CH2), 29.0 (Kδ-CH2), 30.8 (Eγ-CH2), 35.8 (CH2CO2), 42.5 (Kε-CH2), 50.5, 51.6, 52.7 (3 x CHN), 78.9 (COCH2O), 79.2 (CH2Ph), 113.4 (CNO 2), 123.7 (CNO2), 126.1–135.4 (15 x ArC), 147.7 (ArC) 156.1, 160.2 (2 x CONH), 170.6, 171.1, 171.3, 173.6 (4 x CO2) and 199.5 (ketone-CO).

Spectrophotometric assays of caspase inhibition

Recombinant human caspases 1–10 were purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Peptidyl caspase substrates conjugated to p-nitroaniline (pNA), including Ac-YVAD-pNA, Ac-LEHD-pNA, Ac-DEVD-pNA, Ac-VEID-pNA and Ac-IETD-pNA, from Biomol were confirmed to be >95% pure by HPLC, as were the peptidyl inhibitors prepared in this study. Assays were conducted in 96-well microtiter plates and contained: 150 μl of assay buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS, pH 7.5], 10 μl of enzyme in assay buffer (final concentration 1–100 nM), 20 μl of substrate solution (dissolved in DMSO and diluted in assay buffer to 3.9-1000 μM) and 20 μl of inhibitor solution (dissolved in DMSO and diluted in assay buffer to 1-1000 μM). Assays were conducted in triplicate with the assay buffer, substrate and inhibitor preincubated in the microtiter plate at 37°C. Reactions were started by the addition of enzyme warmed to 37°C. Production of pNA was measured by following the absorbance at 405 nm minus that at 650 nm using an ELx808 Ultra microplate reader from Bio-Tek Instruments Inc (Winooski, Vermont).

Progress curves of product formation versus time were fitted using the program KinetiCalc for Windows (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vermont) to measure the initial velocity for reactions over the range of 3.9 – 1000 μM substrate and 0.1 – 100 μM inhibitor. Michaelis-Menton curves of the initial velocity data were fitted by non-linear least squares regression analysis using SigmaPlot version 9.01 with the Enzyme Kinetics Module (Systat Software, Inc., Richmond, CA, USA). The substituted Z-EKD-amok caspase inhibitors were modelled as tight binding inhibitors.42

Tissue culture, cytosolic extract preparation and affinity labelling

The human Jurkat T cell lymphoma cell line was cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The chicken lymphoma B-cell line DT40 expressing chicken procaspase 6 fused to EGFP34 was cultured as previously described.43 To induce apoptosis, cells were treated with 10 μM etoposide for 5. Cytosolic extracts were prepared from untreated and apoptotic cells according to the procedure described by Ruchaud et al.34

Aliquots of apoptotic cytosol were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 2 μM inhibitor. At the completion of the incubation, samples were diluted with 0.5 volume of 3X SDS sample buffer, heated to 95°C for 5 min, subjected to SDS-PAGE on 16% (w/v) acrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden), probed with HRP-coupled streptavidin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Alternatively, blots were probed with antibodies as described below.

Immunoblotting

Samples containing 30 μg of total cellular protein were subjected to electrophoresis for 75 min at 200 V on SDS polyacrylamide minigels containing 16% (w/v) acrylamide and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences) at ambient temperature for 90 min at 40 mA per minigel. Immunoblotting followed by enhanced chemiluminescent detection was performed as described34 using mouse monoclonal anti-DNP from Molecular Probes (Leiden, NL), rabbit anti-EGFP antiserum from Ilan Davis (Univ. of Edinburgh) or rabbit polyclonal anti-chicken caspase-6 (R549) raised against the large subunit of chicken caspase-634 as primary antibodies and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham Biosciences) as secondary antibody.

Affinity purification of derivatized caspase-6

Avidin-Sepharose, monomeric avidin-Sepharose beads, and Slide-a-lyze dialysis slides were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Endogenous biotinylated proteins were removed from apoptotic cytosolic extracts of DT40 cells expressing EGFP:caspase-634 by incubation with avidin-Sepharose beads for 30 min at 4 ºC. Unbound polypeptides were eluted with calcium- and magnesium-free Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and labelled with Z-EK(LC-biotin)D-aomk (12c, 2 μM) by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. Excess inhibitor was removed by dialysis against PBS overnight at 4 ºC. After the labelled fraction was incubated with monomeric avidin-Sepharose beads for 30 min at ambient temperature, the column was washed (three washes of 3X bed volume) with PBS. The non-specifically bound polypeptides were removed with increasingly stringent washes (4 times 3X bed volume of 0.5 M NaCl, 4 times 3X bed volume of 1.0 M NaCl). Bound polypeptides were then eluted with 2 mM biotin in PBS (4 times 3X bed volume). Eluted fractions were concentrated using 5K spin columns (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

Each fraction was loaded onto two SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 16% (w/v) acrylamide. One gel was stained with Colloidal Coomassie Blue (Genomic Solutions, Huntington, UK) and the other was transferred to a nitrocellulose, probed with HRP-coupled streptavidin, stripped (62.5 mM Tris pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 100 mM β-ME),44 reprobed with anti-chicken caspase-6, stripped again and reprobed with anti-EGFP antibody.

MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry

Polypeptide identification was accomplished by peptide mass fingerprinting and sequence database searching.45 After polypeptide bands were excised from Coomassie blue-stained gels, in-gel digestion with trypsin was performed as previously described,46 followed by sample preparation using miniaturized sample concentration/desalting techniques.47 For the mass spectrometric analysis, a PerSeptive Biosystems Voyager DE™STR MALDI-ToF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used. Peptide ion signals were assigned with a mass error less than 50 ppm. Lists of tryptic peptide masses were used to search protein sequence databases using the MS-Fit tool (http://prospector.ucsf.edu/ucsfhtml4.0u/msfit.htm). For positive identification a molecular weight search (MOWSE) score48 of 104 and at least 20% coverage of the protein by the peptide fragments was required.

Flow cytometry

Jurkat cells were treated with 10 μM etoposide (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) plus 10 μM Z-VAD(OMe)-fmk (Calbiochem) or ZEK(DNP)D-aomk (13) at 1 or 10 μM for 5 h, harvested, washed in PBS, fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized in 0.1 % (w/v) Triton X-100 containing 0.1% (w/v) sodium citrate in PBS for 2 min on ice and labeled using the TUNEL (terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase nick end labeling) reaction according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (In situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR red, Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The cells were then analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) using Becton Dickinson CellQuest software.

Supplementary Material

Further documentation of the characterization of target compounds 12a–d and 13 is available as supporting infromation. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial support from the NIH (CA69008 to S.H.K. and W.C.E.) and the Wellcome Trust. W.C.E. is a Principal Research Fellow of the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

The following abbreviations are used: Ac, acetyl; Ac-DEVD-pNA, N-α-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-p-nitroanilide; Ac-IETD-pNA, N-α-acetyl-Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp-p-nitroanilide; Ac-LEHD-pNA, N-α-acetyl-Leu-Glu-His-Asp-p-nitroanilide; Ac-VEID-pNA, N-α-acetyl-Val-Glu-Ile-Asp-p-nitroanilide; Ac-YVAD-pNA, N-α-acetyl-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-p-nitroanilide; aomk, acyloxymethylketone; CHAPS, (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propane-sulfonate; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine; DMF, dimethylformamide; DMPU, 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)pyrimidinone; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; DNP, 2,4-dinitrophenyl; DTT, dithiothreitol; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; Ki, inhibition constant; LC, HO2C(CH2)5NH-; LCLC, HO2C(CH2)5NHCO(CH2)5NH-; MS, mass spectrometry; MOWSE, molecular weight search; NHS, N-hydroxysuccinimide; NMM, N-methylmorpholine; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; NOBA, 3-nitrobenzyl alcohol; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; pNA, para-nitroanilide; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulphate; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; Vmax, maximum velocity; Z , N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl; Z-EK(label)D-aomk, N-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-Glu-Lys(label)Asp-acyloxymethylketone.

References

- 1.Wyllie AH. Glucocorticoid-Induced Thymocyte Apoptosis Is Associated with Endogenous Endonuclease Activation. Nature. 1980;284:555–556. doi: 10.1038/284555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hengartner MO. The Biochemistry of Apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: Enemies Within. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH. Mammalian Caspases: Structure, Activation, Substrates and Functions During Apoptosis. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer U, Janicke RU, Schulze-Osthoff K. Many cuts to ruin: a comprehensive update of caspase substrates. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2003;10:76–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson DW. Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death & Differentiation. 1999;6:1028–1042. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thornberry NA, Rano TA, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Timkey T, Garcia-Calvo M, Houtzager VM, Nordstrom PA, Roy S, Vaillancourt JP, Chapman KT, Nicholson DW. A Combinatorial Approach Defines Specificities of Members of the Caspase Family and Granzyme B. Functional Relationships Established for Key Mediators of Apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:17907–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker N, Talanian R, Brady K. Crystal Structure of the Cysteine Protease Interleukin-1b Converting Enzyme: A (p20/p10)2 Homodimer. Cell. 1994;78:343–352. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson J, Thomson JB, Kim E. Structure and Mechanism of Interleukin-1b Converting Enzyme. Nature. 1994;370:270–275. doi: 10.1038/370270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotonda J, Nicholson DW, Fazil KM, Gallant M, Gareau Y, Labelle M, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Ruel R, Vaillancourt JP, Thornberry NA, Becker JW. The Three-Dimensional Structure of Apopain/CPP32, A Key Mediator of Apoptosis. Nature Structural Biology. 1996;3:619–625. doi: 10.1038/nsb0796-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Y, Fox T, Chambers SP, Sintchak J, Coll JT, Golec JM, Swenson L, Wilson KP, Charifson PS. The structures of caspases-1, -3, -7 and -8 reveal the basis for substrate and inhibitor selectivity. Chemistry & Biology. 2000;7:423–32. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchard H, Donepudi M, Tschopp M, Kodandapani L, Wu JC, Grutter MG. Caspase-8 specificity probed at subsite S(4): crystal structure of the caspase-8-Z-DEVD-cho complex. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2000;302:9–16. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renatus M, Stennicke HR, Scott FL, Liddington RC, Salvesen GS. Dimer Formation Drives the Activation of the Cell Death Protease Caspase 9. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:14250–14255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231465798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufmann SH. Induction of Endonucleolytic DNA Cleavage in Human Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Cells by Etoposide, Camptothecin, and Other Cytotoxic Anticancer Drugs: A Cautionary Note. Cancer Research. 1989;49:5870–5878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Ottaviano Y, Davidson NE, Poirier GG. Specific Proteolytic Fragmentation of Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase: An Early Marker of Chemotherapy-Induced Apoptosis. Cancer Research. 1993;53:3976–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirier GG, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of Poly(ADP-ribose)Polymerase by a Proteinase with Properties like ICE. Nature. 1994;371:346–347. doi: 10.1038/371346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins LM, Kottke TJ, Mesner PW, Basi GS, Sinha S, Frigon N, Jr, Tatar E, Tung JS, Bryant K, Takahashi A, Svingen PA, Madden BJ, McCormick DJ, Earnshaw WC, Kaufmann SH. Activation of Multiple Interleukin-1b Converting Enzyme Homologues in Cytosol and Nuclei of HL-60 Human Leukemia Cell Lines During Etoposide-Induced Apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:7421–7430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faleiro L, Kobayashi R, Fearnhead H, Lazebnik Y. Multiple Species of CPP32 and Mch2 are the Major Active Caspases Present in Apoptotic Cells. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:2271–2281. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margolin N, Raybuck SA, Wilson KP, Chen W, Fox T, Gu Y, Livingston DJ. Substrate and Inhibitor Specificity of Interleukin-1b-Converting Enzyme and Related Caspases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:7223–7228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson EP, Leiting B, Ruel R, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Inhibition of Human Caspases by Peptide-Based and Macromolecular Inhibitors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:32608–32613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martins LM, Mesner PW, Kottke TJ, Basi GS, Sinha S, Tung JS, Svingen PA, Madden BJ, Takahashi A, McCormick DJ, Earnshaw WC, Kaufmann SH. Comparison of Caspase Activation and Subcellular Localization in HL-60 and K562 Cells Undergoing Etoposide-Induced Apoptosis. Blood. 1997;90:4283–4296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boatright KM, Renatus M, Scott FL, Sperandio S, Shin H, Pedersen IM, Ricci JE, Edris WA, Sutherlin DP, Green DR, Salvesen GS. A unified model for apical caspase activation. Molecular Cell. 2003;11:529–41. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohn D, Schulze-Osthoff K, Janicke RU. Caspase-8 can be activated by interchain proteolysis without receptor-triggered dimerization during drug-induced apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:5267–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin S, Lee Y, Kim W, Ko H, Choi H, Kim K. Caspase-2 primes cancer cells for TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by processing procaspase-8. EMBO Journal. 2005;24:3532–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu S, McStay GP, Boucher LM, Mak T, Beere HM, Green DR. In situ trapping of activated initiator caspases reveals a role for caspase-2 in heat shock-induced apoptosis. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;8:72–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baer E, Fischer HOL. Studies on acetone-glyceraldehyde. VII Preparation of l-glyceraldehyde and I-(−)acetone glycerol. Journal of American Chemical Society. 1939;61:761–765. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsunaga H, Sakamaki T, Nagaoka H, Yamada Y. Enantioselective synthesis of (R)- and (S)-4-[(methoxycarbonyl)-methyl]-2-azetidinones from D-glyceraldehyde acetonide. Tetrahedron Letters. 1983;24:3009–3012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remuzon P, Dussy C, Jacqquet JP, Roty P, Bouzard D. Enantioselective synthesis of 1,2-acetonide of (2S,3R)-3-N-Boc-3-amino-4-phenyl-1,2-butanediol. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1996;7:1181–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dess DB, Martin JC. A useful 12-I-5 triacetoxyperiodinane for the selective oxidative of primary or secondary alcohols and a variety of related 12-I-5 species. Journal of American Chemical Society. 1991;113:7277–7287. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolle RE, Hoyer D, Prasad CVC, Schmidt SJ, Helaszek CT, Miller RE, Ator MA. P1 Aspartate-Based Peptide Alpha-((2,6-dichlorobenzoyl)oxy)methyl ketones as potent time-dependent inhibitors of interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1994;37:563564. doi: 10.1021/jm00031a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talanian RV, Quinlan C, Trautz S, Hackett MC, Mankovich JA, Banach D, Ghayur T, Brady KD, Wong WW. Substrate Specificities of Caspase Family Proteases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:9677–9682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Vaillancourt JP, Zamboni R, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Purification and catalytic properties of human caspase family members. Cell Death and Differentiation. 1999;6:362–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mittl PR, Di Marco S, Krebs JF, Bai X, Karanewsky DS, Priestle JP, Tomaselli KJ, Grutter MG. Structure of recombinant human CPP32 in complex with the tetrapeptide acetyl-asp-val-ala-asp fluoromethylketone. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:6539–6547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruchaud S, Korfali N, Villa P, Kottke TJ, Dingwall C, Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Caspase-6 Gene Knockout Reveals a Role for Lamin A Cleavage in Apoptotic Chromatin Condensation. EMBO Journal. 2002;21:1967–1977. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martins LM, Kottke TJ, Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Phosphorylated Forms of Activated Caspases are Present in Cytosol from HL-60 Cells During Etoposide-Induced Apoptosis. Blood. 1998;92:3042–3049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardone MH, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Franke TF, Stanbridge E, Frisch S, Reed JC. Regulation of Cell Death Protease Caspase-9 by Phosphorylation. Science. 1998;282:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allan LA, Morrice N, Brady S, Magee G, Pathak S, Clarke PR. Inhibition of caspase-9 through phosphorylation at Thr 125 by ERK MAPK. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:647–54. doi: 10.1038/ncb1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Billiar TR, Talanian RV, Kim YM. Nitric Oxide Reversibly Inhibits Seven Members of the Caspase Family Via S-Nitrosylation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communication. 1997;240:419–424. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim YM, Kim TH, Chung HT, Talanian RV, Yin XM. Nitric oxide prevents tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced rat hepatocyte apoptosis by the interruption of mitochondrial apoptotic signaling through S-nitrosylation of caspase-8. Hepatology. 2000;32:770–778. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.18291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mannick JB, Schonhoff C, Papeta N, Ghafourifar P, Szibor M, Fang K, Gaston B. S-Nitrosylation of mitochondrial caspases. Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;154:1111–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torok NJ, Higuchi H, Bronk S, Gores GJ. Nitric oxide inhibits apoptosis downstream of cytochrome C release by nitrosylating caspase 9. Cancer Research. 2002;62:1648–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrison JF, Walsh CT. The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Advances in Enzymology & Related Areas of Molecular Biology. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buerstedde JM, Takeda S. Increased Ratio of Targeted to Random Integration After Transfection of Chicken B Cell Lines. Cell. 1991;67:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90581-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaufmann SH, Ewing CM, Shaper JH. The Erasable Western Blot. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;161:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90656-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen ON, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M. Identification of the components of simple protein mixtures by high-accuracy peptide mass mapping and database searching. Amino Acid Sequence. 1997;69:4741–4750. doi: 10.1021/ac970896z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Jensen ON, Podtelejnikov AV, Neubauer G, Shevchenko A, Mortensen P, Mann M. A strategy for identifying gel-separated proteins in sequence databases by MS alone. Biochemical Society Transactions. 1996;24:893–6. doi: 10.1042/bst0240893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gobom J, Nordhoff E, Mirgorodskaya E, Ekman R, Roepstorff P. Sample purification and preparation technique based on nano-scale reversed-phase columns for the sensitive analysis of complex peptide mixtures by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 1999;34:105–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199902)34:2<105::AID-JMS768>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pappin DJ, Hojrup P, Bleasby AJ. Rapid identification of proteins by peptide-mass fingerprinting. Current Biology. 1993;3:327–32. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90195-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Further documentation of the characterization of target compounds 12a–d and 13 is available as supporting infromation. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.