Abstract

Pelvic tilt is often quantified using the angle between the horizontal and a line connecting the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). Although this angle is determined by the balance of muscular and ligamentous forces acting between the pelvis and adjacent segments, it could also be influenced by variations in pelvic morphology. The primary objective of this anatomical study was to establish how such variation may affect the ASIS-PSIS measure of pelvic tilt. In addition, we also investigated how variability in pelvic landmarks may influence measures of innominate rotational asymmetry and measures of pelvic height. Thirty cadaver pelves were used for the study. Each specimen was positioned in a fixed anatomical reference position and the angle between the ASIS and PSIS measured bilaterally. In addition, side-to-side differences in the height of the innominate bone were recorded. The study found a range of values for the ASIS-PSIS of 0–23 degrees, with a mean of 13 and standard deviation of 5 degrees. Asymmetry of pelvic landmarks resulted in side-to-side differences of up to 11 degrees in ASIS-PSIS tilt and 16 millimeters in innominate height. These results suggest that variations in pelvic morphology may significantly influence measures of pelvic tilt and innominate rotational asymmetry.

Keywords: Pelvic Bones, Pelvic Tilt, Pelvimetry, Posture

The angle of pelvic tilt in quiet standing describes the orientation of the pelvis in the sagittal plane. It is determined by the muscular and ligamentous forces that act between the pelvis and adjacent segments. A forward rotation of the pelvis, referred to as anterior pelvic tilt, is accompanied by an increase in lumbar lordosis1 and is believed to be associated with a number of common musculoskeletal conditions, including low back pain2 and anterior cruciate ligament deficiency3,4. In addition, anterior pelvic tilt has been associated with a loss of core stability, and therefore the degree of pelvic tilt has been used to assess core strength5.

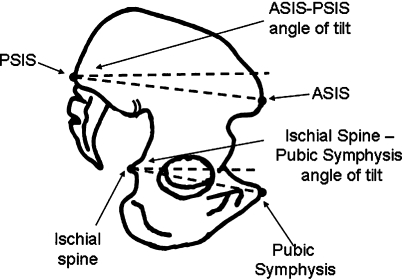

A standard method of assessing the angle of pelvic tilt is depicted in Figure 1, which illustrates the angle between the horizontal and a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). Although this angle is dependent on the muscular and ligamentous forces that act between the pelvis and adjacent segments, it is also dependent on the relative position of the two bony landmarks (ASIS and PSIS) on the innominate bone. Therefore, the use of the ASIS-PSIS angle as a measure of pelvic tilt is in fact a combined measure of 1) the balance of muscular/ligamentous force and 2) pelvic morphology.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the pelvis illustrating the ASIS-PSIS measure of pelvic tilt and the ischial spine-pubic symphysis measure of tilt. The ASIS-PSIS measure is defined as the angle between the horizontal and a line drawn between the ASIS and the PSIS. The ischial spine-pubic symphysis measure is defined as the angle between the horizontal and a line drawn between the ischial spine and the pubic symphysis.

Anterior pelvic tilt and increased lumbar lordosis have been suggested to increase loading on the lumbar spine2. As such, exercise programs are often prescribed to reduce anterior pelvic tilt6. If the decision as to what constitutes anterior pelvic tilt is to be determined from palpation of the ASIS and PSIS, then it is important to understand the influence of pelvic morphology on the ASIS-PSIS angle. If this angle is significantly influenced by morphological variation, then it may not be possible to correctly identify anterior pelvic tilt.

A number of previous research studies have used the ASIS-PSIS angle to investigate differences in pelvic orientation between sufferers of pathology and healthy control subjects3,4,7. In order to correctly interpret the findings of these studies, it is important to examine how much variability in the ASIS-PSIS angle might be attributable to differences in pelvic morphology. Too much variability has the potential to both weaken possible correlations and to hide true differences between subject groups.

As well as a measure of pelvic orientation, the side-to-side difference in ASIS-PSIS angles has been used to assess innominate rotational asymmetry8. Given that there may be side-to-side differences in the relative position of these two bony landmarks on the two innominate bones, this measure may prevent the correct identification of innominate rotational asymmetry. Again, if decisions for clinical management are to be made based on the finding of rotational asymmetry, it is important to understand the potential influence of morphological variability. In a research setting, such variability has the potential to mask true relationships between rotational asymmetry and other clinical measures, such as leg length discrepancy.

There is a need to understand the influence of pelvic morphology on measures of pelvic orientation and on innominate rotational asymmetry. Therefore, a cadaver study was designed with three primary aims. The first was to investigate the variability in the ASIS-PSIS angle across a number of pelves positioned in a fixed anatomical reference position. The second aim was to quantify side-to-side differences in the ASIS-PSIS angle, again across a range of pelves in a fixed reference position. Finally, in order to compare with in vivo studies of pelvic asymmetry, we aimed to investigate the variability in pelvic asymmetry, quantified from side-to-side differences in pelvic height.

Methods

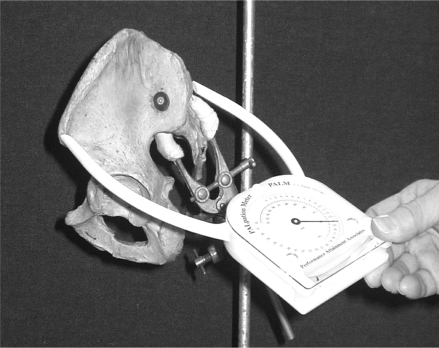

Thirty bony pelves (20 male/10 female) were studied in the dissecting rooms at the University of Manchester, which were licensed for such study by the Human Tissue Authority (and before 2007 by licensing arrangements through H M Inspector of Anatomy). Each pelvis was positioned in the anatomical neutral position suggested by Kendall and McCreary9 in which both ASISs are aligned horizontally and the pubic symphysis and ASISs are in the same vertical plane. This was achieved by first positioning the pelvis against a vertical board, clamping the sacrum with a clamp and heavy-duty stand and then removing the board. The positioning method is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The use of the palmeter to measure pelvic tilt.

In order to answer our first research aim, the ASIS-PSIS angle was measured on each side of the pelvis, using a palmeter (Palpation Meter, Performance Attainment Associated, St. Paul, MN, US). The measurement procedure for this instrument is illustrated in Figure 2 and involved positioning the two arms of the palmeter in contact with the two bony prominences and reading off the angle. Measurements taken on five specimens, repeated after a week, gave an Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.92 with a standard error of measure (SEM) of 0.5 degrees.

Sinnatamby10 proposed an alternative pelvic anatomical neutral position to the method used by Kendall and McCreary. This is defined as the position in which the ischial spine and the pubic symphysis are in the same horizontal plane (Figure 1). We were interested in the influence of pelvic morphology on pelvic tilt; therefore, the angle between the horizontal and a line from the ischial spine to the pubic symphysis was measured for each pelvis positioned as described above. This measurement was obtained by placing a steel rule in contact with these two landmarks and then positioning the palmeter along the length of the rule. Again, measurements were taken from both the left and right sides of each pelvis. Measurements taken on five specimens, repeated after a week, gave an intra-tester reliability coefficient of ICC = 0.98 with a SEM = 1.1 degrees.

In order to answer our second research aim, the side-to-side difference between the ASIS-PSIS angle was calculated for each pelvis. In addition, as we were interested in the influence of morphology on pelvic asymmetry, we also used the side-to-side difference in the ischial spine-pubic symphysis angle to quantify pelvic asymmetry. In order to answer the final research aim, relating to pelvic asymmetry, the side-to-side difference in height of the left and right innominate bone was obtained. This was defined as the distance between the bottom of the ischial tuberosity and the top of the iliac crest. The palmeter was also used to measure this distance by positioning the arms in contact with the appropriate points on the pelvis and reading the measured distance. Measures were repeated after one week and intra-tester reliability coefficients calculated. These were found to be ICC = 0.94 with a SEM = 1.9 mm. This final measure of pelvic asymmetry was chosen as it allowed comparison with previously published data.

Results

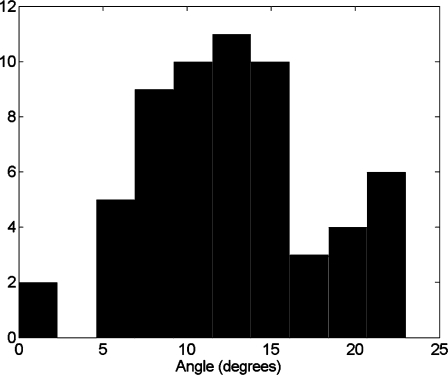

With the pelvis fixed in the standard reference position, the ASIS-PSIS angle (calculated as the mean of both sides) was found to vary from 0 to 23 degrees with a mean of 13 degrees and standard deviation of 5 degrees. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test showed that the data were distributed normally. Analysis of the ischial spine-pubic symphysis angle gave a similar range of values (4 to 26 degrees) with a mean of 14 and standard deviation of 5 degrees. Again, a K-S test showed this variable to be normally distributed. The ASIS-PSIS measures for each specimen are given in Table 1 and the distribution of this angle shown with a histogram in Figure 3.

TABLE 1.

Left and right ASIS-PSIS angles, side-to-side dif erences, and mean angles for every specimen used in the study.

| Subject Number | Sex | ASIS - PSIS angle (right) | ASIS - PSIS angle (left) | Side-to-side difference in ASIS - PSIS angle | Mean ASIS - PSIS angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | f | 13 | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| 2 | f | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 3 | f | 8 | 9 | −1 | 9 |

| 4 | f | 8 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| 5 | f | 12 | 14 | −2 | 13 |

| 6 | m | 14 | 13 | 1 | 14 |

| 7 | m | 6 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| 8 | m | 15 | 21 | −6 | 18 |

| 9 | m | 9 | 12 | −3 | 11 |

| 10 | m | 15 | 16 | −1 | 16 |

| 11 | m | 6 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| 12 | m | 13 | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| 13 | m | 10 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| 14 | m | 13 | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| 15 | f | 20 | 21 | −1 | 21 |

| 16 | m | 20 | 21 | −1 | 21 |

| 17 | m | 15 | 10 | 5 | 13 |

| 18 | m | 18 | 21 | −3 | 20 |

| 19 | m | 13 | 17 | −4 | 15 |

| 20 | f | 14 | 16 | −2 | 15 |

| 21 | m | 12 | 14 | −2 | 13 |

| 22 | f | 8 | 10 | −2 | 9 |

| 23 | f | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 24 | m | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 25 | m | 5 | 7 | −2 | 6 |

| 26 | m | 16 | 17 | −1 | 17 |

| 27 | f | 20 | 19 | 1 | 20 |

| 28 | m | 23 | 22 | 1 | 23 |

| 29 | m | 9 | 11 | −2 | 10 |

| 30 | m | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

Figure 3.

Histogram to show the distribution of the ASIS-PSIS angle across all the specimens. The left and right values have been considered separately for this representation of the data.

Although it has been suggested that the ASIS-PSIS angle in female pelves may be larger than that in male pelves11, an unpaired t-test showed there to be no significant difference in this angle (95% CI −2.8 degrees to 5.4 degrees). Similarly, with the ischial spine-pubic symphysis angle, there was also no significant difference in gender among the specimens (95% CI −2.3 degrees to 5.8 degrees).

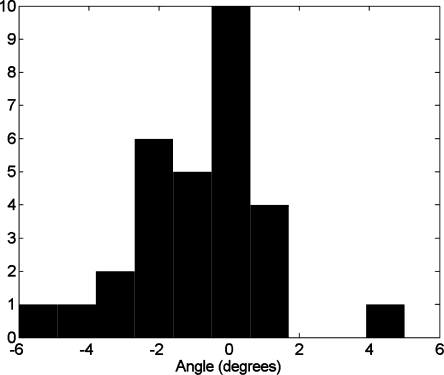

The side-to-side differences in the ASIS-PSIS angle, taken as the difference between the left and right ASIS-PSIS angle, ranged from −6 degrees (left more anteriorly tilted) to 5 degrees (right more anteriorly tilted) with a mean of −1 degrees and standard deviation of 2 degrees. This result demonstrates that, on average, the location of the ASISs and PSISs was such that there appeared to be a relative anterior rotation of the left innominate bone relative to the right although the large range and standard deviation shows there was considerable variation between specimens (Table 1). This variation is clearly illustrated in the histogram of the side-to-side differences, shown in Figure 4. A similar variation was obtained using the ischial spine-pubic symphysis measure of tilt, which displayed a range of −3 degrees to 5 degrees and mean of 1 degree and standard deviation of 2 degrees. In contrast to the ASIS-PSIS measure, this demonstrates that, on average, the location of the ischial spines and pubic symphysis was such that there appeared to be a relative anterior rotation of the right innominate bone relative to the left.

Figure 4.

Histogram demonstrating the distribution of the side-to-side difference in the ASIS-PSIS angle across all specimens. A positive value indicates that the right side is more anteriorly tilted than the left.

The measure of asymmetry, taken as the difference in height between the left and right innominate bone, showed a range of −7mm (left side larger) to 9mm (right side larger) with a mean of 2mm and standard deviation of 5mm. The large standard deviation in this measurement again demonstrates the large variability in asymmetry across the different specimens.

Discussion

The first primary aim of this study was to establish whether pelvic morphology may significantly influence measures of pelvic orientation. Following this aim, the ASIS-PSIS angle was measured in 30 cadaver specimens fixed in an anatomical reference position. The results of this investigation showed a range in the ASIS-PSIS angle of 23 degrees across the 30 pelves, values similar to those reported with in vivo studies1,12,13. For example, Kroll et al12 reported between 3–22 degrees of tilt in 54 normal subjects and Levine and Whittle1 a mean of 11.3 degrees and SD of 4.3 degrees across 20 female subjects. Similarly, Gilliam et al13 obtained a range of between 4–21 degrees in a cohort of 15 low back pain patients. As with the present study, these researchers used an inclinometer to measure the angle between the horizontal and the ASIS-PSIS line. Our findings also agree with data reported by Deusinger14, who measured the ASIS-PSIS angle in 13 cadaver pelves and found a variation of between −9 degrees (posterior tilt) and 12 degrees (anterior tilt), although it was unclear how he defined a pelvic anatomical neutral position.

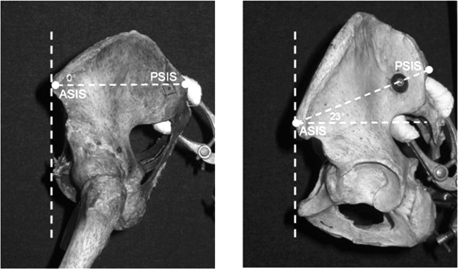

The similar findings to those reported in in vivo studies1,12,13 suggest significant potential for morphological variation across pelves that could potentially influence the standard clinical measurement of pelvic tilt. It is possible that differences of up to 23 degrees in the ASIS-PSIS angle could reflect differences in morphology rather than differences in muscular and ligamentous forces acting between the pelvis and adjacent segments. This is best illustrated using an extreme example. Figure 5 shows two pelves aligned in the standard reference position, with an ASIS-PSIS angle in the first specimen of 0 degrees and in the second of 23 degrees. The additional finding of similar range (22 degrees) in the pubic symphysis-ischial spine angle gives further support to the idea that there is considerable morphological variation between pelves. Again, this may have a significant influence on associated measures of tilt.

Figure 5.

Different values of ASIS-PSIS tilt. Two different pelves both positioned in pelvic neutral according to Kendall and McCreary9.

Given the significant morphological variability across different pelves, the use of the ASIS-PSIS angle to quantify pelvic tilt may result in weaker correlations between pelvic tilt and other clinical measurements than would be obtained if muscle and ligament forces could be measured directly. For example, it is expected clinically that an increase in lumbar lordosis would be accompanied by an increase in anterior pelvic tilt. As such, a number of researchers have attempted to correlate the ASIS-PSIS angle with a measure of lumbar lordosis, which can be reliably measured using a flexible draftman's curve15,16. Walker et al17 investigated this relationship across 31 subjects but they found only a very weak correlation (r=0.32). Similar results were obtained by Kroll et al12, who studied 54 subjects and found a correlation of r=0.33.

In addition to weakening potential correlations, the significant variability in pelvic morphology has the potential to mask true differences in pelvic tilt between different groups of subjects. Given that the standard deviation of the ASIS-PSIS angle in our study was 5 degrees, we would suggest that to have a strong effect size (i.e., Cohen's d>0.8), group differences in the ASIS-PSIS angle should be at least 4 degrees. This should ensure that differences in the ASIS-PSIS angle between groups reflects any true differences in the muscular and ligamentous forces that act between the pelvis and adjacent segments and not just differences in pelvic morphology.

Bullock-Saxton7 compared the ASIS-PSIS angle between a group of normal subjects (n=25) and a group of low back pain sufferers (n=30) but found no difference (P<0.05) in this measurement of tilt (no values for the ASIS-PSIS angle were reported in this paper). One explanation for this finding could be that a large variation in pelvic morphology masked any differences in tilt. Hertel et al3 compared the angle of pelvic tilt between a group of normal subjects (n=20) and a group of subjects with a history of anterior cruciate ligament injury (n=20). In contrast to the results of Bullock-Saxton7, they found a significant difference in the angle of tilt with the normal group having a mean of 1.7 degrees and the ACL group having a mean of 3.2 degrees. Although this difference was statistically significant (P<0.05), within the context of our results, this difference represents only a small effect size (d=0.3).

The second primary aim of this study was to investigate whether side-to-side differences in pelvic morphology could influence clinical measures of innominate rotational asymmetry. To address this aim, the difference between the ASIS-PSIS angle was noted for each specimen when positioned in a symmetric reference orientation. This study found a surprisingly large range in the side-to-side difference of the ASIS-PSIS angle: 11 degrees. This range is similar to the range of values reported in vivo by Krawiec et al8. Given this similarity, our data would suggest that morphological variation between pelves will have significant influence on associated clinical measures of innominate rotational asymmetry.

Leg length discrepancy has the potential to cause innominate rotational asymmetry18. As such, a correlation would be expected between innominate rotational asymmetry and leg length discrepancy. Krawiec et al8 investigated this relationship, quantifying asymmetric innominate rotation using the ASIS-PSIS angles but they found only a weak correlation (r=0.33). Again, a possible explanation for these findings is that morphological variation in the positioning of the ASIS and PSIS weakened what, otherwise, might have been a stronger correlation.

Significant pelvic asymmetry, due to variations in pelvic morphology, was also demonstrated using the ischial spine-pubic symphysis angle and the side-to-side difference in pelvic height. This latter finding is in agreement with Badii et al19, who used radiographic techniques and defined a measure of innominate asymmetry using the distance from the iliac crest to the acetabuli. Such pelvic asymmetry has the potential to reduce the validity of using the difference in height of the iliac crests as an indirect measure of leg length discrepancy. This was verified in a recent study by Petrone et al20, who obtained values of ICC=0.76–0.78 for the validity of using this measure as an indirect estimate of leg length discrepancy.

Clinical Relevance

The ASIS-PSIS angle should not be used in isolation to assess pelvic orientation. Additional factors should also be taken into consideration, such as the depth of the lumbar lordosis and the hip joint angle in standing with neutral knee joint alignment. Assessment of innominate rotational asymmetry using the ASIS-PSIS landmarks must also be viewed with caution.

Conclusion

This study found significant variation in the ASIS-PSIS angle across 30 cadaver pelves all positioned in a fixed anatomical reference position. This variation may significantly influence clinical measures of pelvic tilt and has the potential to weaken any true correlations between tilt and other clinical measurements. The study also showed significant side-to-side variability in the relative position of the ASIS and PSIS landmarks. Again, this variability has the potential to significantly influence clinical measures of innominate rotational asymmetry.

Footnotes

This work was supported by an EPSRC grant (UK), reference number GR/S59710/01

Contributor Information

Stephen J. Preece, Research Fellow, Centre for Rehabilitation and Human Performance, University of Salford, Manchester, UK..

Peter Willan, Professor of Human Anatomy, Human Anatomy, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK..

Chris J. Nester, Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Rehabilitation and Human Performance Research, University of Salford, Manchester, UK..

Philip Graham-Smith, Lecturer in Sports Science, Centre for Rehabilitation and Human Performance Research, University of Salford, Manchester, UK..

Lee Herrington, Lecturer in Sports Rehabilitation, Centre for Rehabilitation and Human Performance Research, University of Salford, Manchester, UK..

Peter Bowker, Professor of Rehabilitation Research, Centre for Rehabilitation and Human Performance Research, University of Salford, Manchester, UK..

REFERENCES

- 1.Levine D, Whittle MW. The effects of pelvic movement on lumbar lordosis in the standing position. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;24:130–135. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1996.24.3.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jull GA, Janda V. Muscles and motor control in lower back pain: Assessment and management. In: Twomey LT, Talyor JR, editors. Physical Therapy of the Lower Back. 1st ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hertel J, Dorfman JH, Brahman RA. Lower extremity malalignments and anterior cruciate ligament injury history. J Sport Sci Med. 2004;3:220–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loudon JK, Jenkins W, Loudon KL. The relationship between static posture and ACL injury in female athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;24:91–97. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1996.24.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willson JD, Dougherty CP, Ireland ML, Davis IM. Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:316–325. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine D, Walker JR, Tillman LJ. The effect of abdominal muscle strengthening on pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis. Physiother Theory & Practice. 1997;13:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bullock-Saxton J. Postural alignment in standing: A repeatability study. Aust J Physiother. 1993;39:25–29. doi: 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krawiec CJ, Denegar CR, Hertel J, Salvaterra GF, Buckley WE. Static innominate asymmetry and leg length discrepancy in asymptomatic collegiate athletes. Man Ther. 2003;8:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s1356-689x(03)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendall FP, McCreary EK. Muscles, Testing and Function. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinnatamby CS. Last's Anatomy: Regional and Applied. 10th ed. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahrmann SA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. 1st ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroll PG, Arnofsky SL, Peckham S, Rabinowitz A. The relationship between lumbar lordosis and pelvic tilt angle. J Back Musculoskeletal Rehabil. 2000;14:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilliam J, Brunt D, MacMillan M, Kinard RE, Montgomery WJ. Relationship of the pelvic angle to the sacral angle: Measurement of clinical reliability and validity. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20:193–199. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.20.4.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deusinger RH. Validity of pelvic tilt measurements in anatomical neutral position. J Biomech. 1992;25:764. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burton AK. Regional lumbar sagittal mobility: Measurement by flexicurves. Clin Biomech. 1986;1:20–26. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(86)90032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovell FW, Rothstein JM, Personius WJ. Reliability of clinical measurements of lumbar lordosis taken with a flexible rule. Phys Ther. 1989;69:96–105. doi: 10.1093/ptj/69.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker ML, Rothstein JM, Finucane SD, Lamb RL. Relationships between lumbar lordosis, pelvic tilt, and abdominal muscle performance. Phys Ther. 1987;67:512–516. doi: 10.1093/ptj/67.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuchera ML. Postural considerations in coronal and horizontal planes. In: Ward RC, editor. Foundations for Osteopathic Medicine. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badii M, Shin S, Torreggiani WC, et al. Pelvic bone asymmetry in 323 study participants receiving abdominal CT scans. Spine. 2003;28:1335–1339. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065480.44620.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrone MR, Guinn J, Reddin A, Sutlive TG, Flynn TW, Garber MP. The accuracy of the Palpation Meter (PALM) for measuring pelvic crest height difference and leg length discrepancy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:319–325. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.6.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]