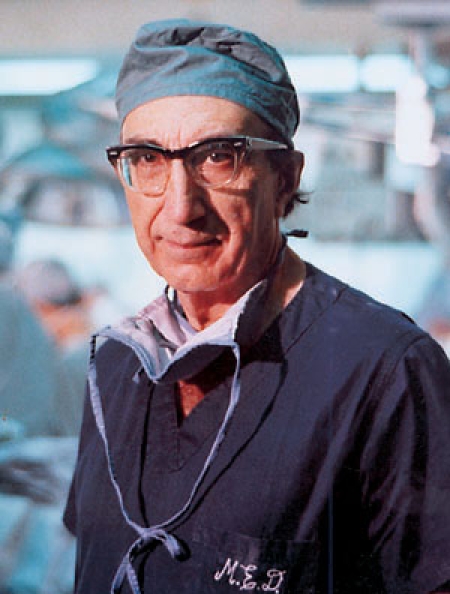

Figure. Michael E. DeBakey, MD

Born on 7 September 1908, Dr. Michael Ellis DeBakey died on 11 July 2008, just 8 weeks short of a century of living. During his long and productive life, he made significant contributions to surgical science, to medical education at Baylor College of Medicine and affiliated hospitals, and to the reputation of the Texas Medical Center as a center for the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, to a Lebanese family, Dr. DeBakey attended Tulane University and Medical School in New Orleans, where he graduated with high honors. He completed a surgical residency under Dr. Alton Ochsner, during which Dr. DeBakey modified a roller-type pump used for direct blood transfusion. The pump served as a model in the early development of heart–lung bypass for surgery. In addition, Dr. DeBakey was acclaimed for his interest in and his publications about venous thrombosis and carcinoma of the lung. After completing his surgical residency at New Orleans's Charity Hospital and spending 2 years receiving additional training from several eminent surgeons in Europe, Dr. DeBakey was invited to return to Tulane to serve on its faculty.

In 1948, Dr. DeBakey was appointed head of the new Department of Surgery at Baylor University College of Medicine, which had recently moved from Dallas to Houston. His early staff included me and Drs. Oscar Creech, B.W. Haynes, and John Howard, all of whom went on to achieve outstanding academic reputations. Dr. DeBakey became interested in the surgical repair of aortic aneurysms and drew worldwide attention to the aggressive treatment and repair of these lesions. With the advent of temporary cardiopulmonary bypass, he introduced many innovative cardiovascular techniques. Vascular grafts of Dacron fabric, named after Dr. DeBakey himself, became standard for the replacement of arteries and veins. Dr. DeBakey played an active role in the treatment of arterial occlusive disease and claimed many “firsts” in reconstructive procedures, including the first successful graft replacements of thoracic aortic aneurysms. He also became involved in the repair and replacement of intracardiac structures, and he was an early participant in cardiac transplantation. His interest in mechanical support devices for the failing left ventricle led him to obtain a federal grant to develop assist devices and a total artificial heart. He actually implanted his early-model left ventricular assist devices in a number of patients after cardiac surgery, producing one long-time survivor—the first patient ever to benefit from such a device. One of his research staff members collaborated with me to develop a total artificial heart, which was implanted in 1969 in a 47-year-old patient as a bridge to cardiac transplantation. A controversy followed, which led to my resignation from the full-time faculty at Baylor. A period of 4 decades ensued during which Dr. DeBakey and I lost communication.

Dr. DeBakey made many contributions outside of surgical practice for the benefit of the medical profession. During his Army service in World War II, he promoted the placement of medical personnel closer to the front lines, thereby fostering the development of mobile army surgical hospital (MASH) units. In addition, he was not only a major contributor to the creation of the Veterans' Administration Hospital System, but he also promoted its inclusion of first-class hospitals, most with close university affiliations. He played an important role in improving the National Library of Medicine, and he maintained close liaisons with senators and congressional representatives regarding medical affairs. During the Johnson administration, he chaired the President's Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke. He also became the first physician to serve 3 terms on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Advisory Council of the National Institutes of Health.

During his career, Dr. DeBakey received countless awards and acknowledgments for his many contributions—too many to enumerate here. He seemed to value most the Lasker Foundation medal, which he considered to be America's Nobel Prize. He also received the Presidential Medal of Freedom with Distinction—the highest civilian award a United States citizen can receive—from President Lyndon Johnson. Recently, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, which had been awarded to only 3 other physicians since the first such medal was awarded to General George Washington in 1776.

In 2006, Dr. DeBakey underwent a serious open heart procedure for an acute dissection of the ascending aorta, from which he made a miraculous recovery. It was soon after that that we resumed a friendly relationship: I was gratified when Dr. DeBakey accepted my invitation to become an honorary member of the Denton A. Cooley Cardiovascular Society, and I was honored when he arranged a similar membership for me in the DeBakey International Surgical Society.

Upon Dr. DeBakey's passing, accolades were conferred by many of the citizens of Houston. His body lay in state at City Hall—a “first” in itself—and an impressive memorial service was held at the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, where as many as 2,000 individuals paid their respects.

Dr. DeBakey's legacy is too expansive to describe fully. Among the notable Houston institutions that bear his name are the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, the Michael E. DeBakey High School for Health Professions, Baylor College of Medicine's Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, and the Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center. His more than 1,600 written works—articles, chapters, and books—will continue to be instructive to present and future health professionals, and the many awards and scholarships established by him or in his name will continue to aid and inspire them. His work has given the city of Houston a global reputation for cardiovascular medicine. But his greatest legacy by far is the people, both patients and colleagues, who benefited from his energy, his inventiveness, and his boundless enthusiasm for his life-saving work. I am pleased to be among them.

Denton A. Cooley, MD

Surgeon-in-Chief and President Emeritus, Texas Heart Institute