Abstract

Objective:

To assess the effects of population tobacco control interventions on social inequalities in smoking.

Data sources:

Medical, nursing, psychological, social science and grey literature databases, bibliographies, hand-searches and contact with authors.

Study selection:

Studies were included (n = 84) if they reported the effects of any population-level tobacco control intervention on smoking behaviour or attitudes in individuals or groups with different demographic or socioeconomic characteristics.

Data extraction:

Data extraction and quality assessment for each study were conducted by one reviewer and checked by a second.

Data synthesis:

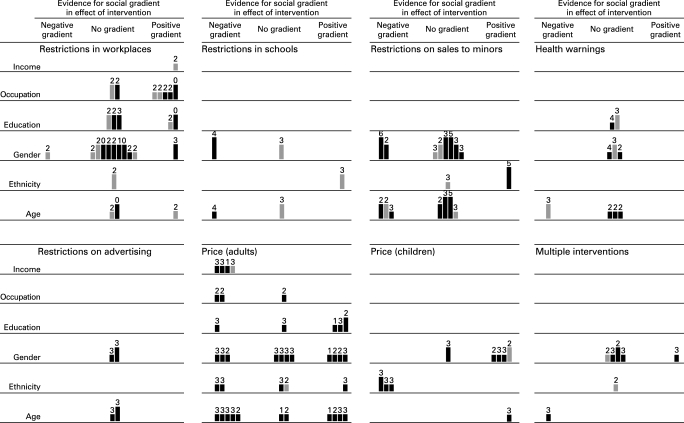

Data were synthesised using graphical (“harvest plot”) and narrative methods. No strong evidence of differential effects was found for smoking restrictions in workplaces and public places, although those in higher occupational groups may be more likely to change their attitudes or behaviour. Smoking restrictions in schools may be more effective in girls. Restrictions on sales to minors may be more effective in girls and younger children. Increasing the price of tobacco products may be more effective in reducing smoking among lower-income adults and those in manual occupations, although there was also some evidence to suggest that adults with higher levels of education may be more price-sensitive. Young people aged under 25 are also affected by price increases, with some evidence that boys and non-white young people may be more sensitive to price.

Conclusions:

Population-level tobacco control interventions have the potential to benefit more disadvantaged groups and thereby contribute to reducing health inequalities.

Reducing social inequalities in health is a priority for health policy in many countries.1 Although the extent and causes of health inequalities have been extensively researched, we know remarkably little about the actual effects of measures to reduce such inequalities,2 and it is possible that a strategy that improved health in the population overall might actually widen inequalities between social groups if its benefits were concentrated among the better-off.3

Smoking has been shown to be a major contributor to social inequalities in mortality and is the single greatest contributor to preventable illness and premature death in the United Kingdom.4 5 The importance of interventions to reduce the association of smoking with disadvantage is well recognised6 and is reflected, for example, in the target set by the Department of Health to reduce the prevalence of smoking in “manual groups” from 32% to 26% by 2015.7 Smokers from lower socioeconomic groups may be less likely than those from higher socioeconomic groups to quit as a result of participating in individually targeted approaches such as smoking cessation services, although this social gradient in quit rates may be offset by a greater penetration of smoking cessation services in disadvantaged areas.8 The potential contribution of population-level interventions, such as restrictions on tobacco advertising and on smoking in public places, to reducing social inequalities in smoking has been less well researched.9 We carried out a systematic review of the differential effects of population-level tobacco control interventions by evaluating their effects in groups with different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Our overall aim was to identify which interventions are most likely to be effective in reducing smoking-related health inequalities.

METHODS

Search strategy

We identified primary studies in any language by searching medical, nursing, psychological, social science and grey literature databases from their inception dates to January 2006. We did not limit our searches by study design. We also examined bibliographies and conference abstracts, hand-searched key journals and contacted authors for additional information where necessary. Further details can be found in our full report at http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/projects/tobacco-control.htm.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

Titles and abstracts were assessed for relevance independently by two reviewers. Potentially relevant studies were assessed for inclusion independently by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved through discussion and, where necessary, the involvement of a third reviewer.

We included studies of any design that assessed the effects of a population-level tobacco control intervention (see box) in smokers, people at risk of taking up smoking, people at risk of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) or the general population. Studies had to report quantitative outcomes for individuals or groups with different demographic or socioeconomic characteristics. Eligible outcomes included changes in smoking behaviour (such as prevalence or consumption), indirect measures of tobacco consumption (such as illegal sales to minors or quantity of smuggled cigarettes), exposure to ETS, intermediate outcomes (such as changes in knowledge or attitudes), process measures (such as participation rates), implementation measures (such as enforcement of policy changes) and any health outcomes (such as mental health or wellbeing), as well as adverse or unintended effects. We also included qualitative data where these were linked to an included quantitative study. We excluded studies of interventions conducted exclusively within closed settings (such as psychiatric or addiction treatment facilities, detention centres or prisons) because this review was concerned with effects in the wider population. We also excluded studies that assessed the effects of restrictions on sales to minors (youths) by only reporting test purchases as outcomes. This is because we considered the minors undertaking the test purchases at retail outlets to be part of the intervention, their purchase attempts being a device for evaluating the implementation and enforcement of the intervention. Such “test purchases” alone did not provide sufficient data for our purposes on the differential effects of an intervention between social groups. We did, however, include studies that assessed the effects of restrictions on sales to minors by reporting evaluation data from a larger population (such as surveys of local schoolchildren).

What is a population-level tobacco control intervention?

We defined population-level tobacco control interventions as those applied to populations, groups, areas, jurisdictions or institutions with the aim of changing the social, physical, economic or legislative environments to make them less conducive to smoking. These are approaches that mainly rely on state or institutional control, either of a link in the supply chain or of smokers’ behaviour in the presence of others. Our definition was based on our pilot study10 and scoping searches for the systematic review and includes interventions such as:

Tobacco crop substitution or diversification

Removing subsidies on tobacco production

Restricting trade in tobacco products

Measures to prevent smuggling

Measures to reduce illicit cross-border shopping

Restricting advertising of tobacco products

(Enforcing) restrictions on selling tobacco products to minors

Mandatory health warning labels on tobacco products

Increasing the price of tobacco products

Restricting access to cigarette vending machines

Restricting smoking in the workplace

Restricting smoking in public places.

Such approaches could also form part of wider, multifaceted interventions in schools, workplaces or communities.

We did not include interventions whose main aim was to strengthen the capacity of individuals to stop smoking or to resist taking up smoking, even if these interventions were applied to whole groups or populations (for example, mass media health education campaigns). These are approaches that mainly rely on individuals engaging voluntarily with measures intended to help them.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted and the quality of each study was assessed independently by one reviewer and checked by a second. We summarised study quality using a scale of suitability of study design adapted from the criteria used for the Community Guide of the US Task Force on Community Preventive Services11 and a six-item checklist of quality of execution adapted from the criteria developed for the Effective Public Health Practice Project in Hamilton, Ontario12 (see table on Tobacco Control website). We extracted outcome, process and implementation data stratified by the sociodemographic characteristics specified in the PROGRESS criteria (place of residence, race or ethnicity, occupation, gender, religion, educational level, socioeconomic status (for example, represented by income), and social capital)13 and also by age for interventions targeted at populations considered specifically “at risk” of smoking because of their age (adolescents and young adults). For studies where it appeared that relevant data on differential effects may have been collected but not reported, we contacted authors to request additional data.

Data from qualitative studies were extracted using methods adapted from those developed by Britten et al98 and their quality was assessed using published prompts for appraising qualitative research.99 Any disagreements at each stage were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, the involvement of a third member of the review team.

Data synthesis

We adopted a hypothesis-testing approach to examine the balance of evidence about the differential effects of interventions and synthesised the data using a combination of graphical and narrative methods, including a novel matrix or “harvest plot” (see fig 2).100 For each category of intervention and dimension of inequality, we populated the relevant row of this matrix by placing a bar representing each study in one of three columns according to which of three competing hypotheses were most strongly supported by the results of that study:

Figure 2. Evidence for social gradients in effects of interventions. A „supermatrix” covering all categories of intervention consisting of six rows (one for each dimension of inequality) and three columns (one for each of the three competing hypotheses about the differential effects of each category of intervention). Each study is represented by a mark in each row for which that study had reported relevant results. Studies with hard behavioural outcome measures are indicated with full-tone (black) bars, and studies with intermediate outcome measures with half-tone (grey) bars. The suitability of study design is indicated by the height of the bar, where the highest bars represent the most suitable study designs (categories A and B) and the lowest bars represent the least suitable (category D). Each bar is annotated with the number of other methodological criteria (maximum six) met by that study.

The null hypothesis that for any given demographic or socioeconomic characteristic there was no social gradient in the effectiveness of the intervention

The alternative hypothesis that there was a positive social gradient in effectiveness, meaning that the intervention was more effective in more advantaged groups (defined for this purpose as the more affluent, those with a higher level of education, those in more skilled occupational groups, males, older people or those in the majority or most advantaged racial or ethnic group in the context of a particular study)

The alternative hypothesis that there was a negative social gradient in effectiveness, meaning that the intervention was more effective in more disadvantaged groups.

RESULTS

We screened a total of 17 064 references, identified 970 potentially eligible papers and finally included 84 studies (reported in 90 papers) (fig 1). We found only one qualitative study conducted in conjunction with a quantitative study.22 We approached six authors for additional data but none was forthcoming.

Figure 1. Process of study selection.

We found relevant evidence for seven categories of intervention: restrictions on smoking in workplaces and public places, restrictions on smoking in schools, restrictions on sales to minors, health warnings on tobacco products, restrictions on advertising of tobacco products, price of tobacco products and multifaceted interventions (see fig 2). Further details of the studies included in each category can be found in our full report at http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/projects/tobacco-control.htm.

The included studies reported outcomes by race or ethnicity, occupation, gender, educational level, income or age. As no studies reported outcomes by place of residence, religion or level of social capital these characteristics were excluded from our analysis.

Stronger designs tended to have been used for studies of the effects of restrictions on smoking in workplaces, public places and schools and restrictions on sales to minors, of which three were cluster randomised controlled trials.31 32 34 Studies of other types of intervention were predominantly cross-sectional or retrospective.

Studies of restrictions on sales to minors were the most likely to fulfil the criteria for quality of execution, with one study meeting all six criteria31 and two studies meeting five.32 34 Two studies of restrictions on smoking in schools met four criteria.28 29 The remaining studies in this review met between zero and three of the criteria.

Restrictions on smoking in workplaces and public places

Fourteen studies, nine published between 1981 and 1999 and five published more recently, evaluated smoking restrictions or bans in the workplace or in public places14–27 in the United States,14 16 20 21 23–26 Australia,15 New Zealand,27 Israel,17 Finland,18 Scotland22 and Wales.19 The interventions consisted of a total ban on indoor smoking,14 15 17 24 25 27 a smoking ban with exceptions,22 restricting smoking to designated rooms or areas18 19 21 23 or displaying no-smoking signs in a hospital lobby.16 The nature of the smoking ban was unclear in two studies.20 26 The balance of evidence from five comparatively weak studies suggested that, if anything, restrictions on smoking in workplaces may be more effective for staff in higher occupational grades.19 22–25 We found insufficient evidence of differential effects by income,26 educational level14 17 18 25 26 or ethnicity,27 inconsistent evidence of differential effects by age, and no evidence of differential effects by gender.14–21 24–26

Restrictions on smoking in schools

Three studies assessed the effects of restrictions on smoking in schools, one published in 199929 and two published in 2005.28 30 These examined the effects of a smoking policy in a UK school,29 student beliefs and support for a school smoking ban in a mostly non-white population in California30 and the effects of enforcement action on student smoking behaviour and attitudes in another US population.28 These studies suggested that restrictions on smoking in schools may be more effective in girls than in boys29 and in middle-school than in high-school students,28 and that attitudes were more favourable in non-Hispanic students than in Hispanic students.30 No studies provided evidence about possible differential effects by parental income, occupation or educational level.

Restrictions on sales to minors

Thirteen studies, most published between 2000 and 2005, evaluated restrictions on sales to minors in the United States,31–34 36 38 42 Sweden,41 Finland,37 Australia39 40 43 and New Zealand35 in populations aged between 13 and 18 years of age. The interventions included education of retailers and the community, enforcement of legislation, or both. The evidence from two studies (one of an educational intervention and one of combined education and enforcement) suggested that girls may be less likely to use tobacco as a result of the intervention than boys.31 33 The evidence from six other studies (four of an enforcement intervention and two of combined education and enforcement) on differential effects by gender was inconsistent.32 35 37 39–41 One study of combined education and enforcement found that the intervention was less effective in non-white students than in white students.34 A second weaker study of an enforcement intervention found no evidence of differential effects by ethnicity.35 Three studies (two of an enforcement intervention and one of combined education and enforcement) found larger effects in younger students than in older students.33 37 41 Four other studies (one of an enforcement intervention and three of combined education and enforcement) found inconsistencies in effects by age.32 35 39 43 No studies provided evidence about possible differential effects by parental income, occupation or educational level.

Health warnings on tobacco products

Five studies assessed the effects of health warnings and labelling of contents on tobacco products in the general population,46 47 50 young adults48 or schoolchildren.49 Studies were published between 1997 and 2005 and were conducted in Australia,46 Canada,47 48 the United States49 and The Netherlands.50 We found no consistent evidence of differential effects on smoking behaviour by education for smoking behaviour46 50 or on smoking attitudes or behaviour by gender.46 48 50 In three studies of young people, health warnings did not appear to change attitudes or smoking behaviour.47–49 No studies provided evidence about possible differential effects by income, occupation or ethnicity.

Restrictions on advertising of tobacco products

Two studies assessed the effects of advertising restrictions on children and young people. One study was set in Hong Kong and published in 2004.44 The other used national statistics from 1992 to assess smoking prevalence among adolescents in Norway, Finland, New Zealand and France.45 We found no evidence of differential effects by gender or age. No studies provided evidence about possible differential effects by parental income, occupation, educational level or ethnicity.

Price of tobacco products

Forty-two studies provided information about the effects of the price of tobacco products on smoking behaviour. Most were econometric analyses applying statistical models to cross-sectional or longitudinal survey data from various time periods between 1961 and 2003. These studies modelled the relation between the decision to smoke or the quantity of cigarettes smoked and changes in price or tax. Most used survey data from the United States with 20 studies reporting data for adolescents or college students only52 56 57 60 61 64 68 69 72 76 78–83 88 89 91 92 and 13 reporting data for adults only or for young people and adults combined.54 55 58 59 62 63 65–67 71 74 77 87 Three studies were conducted in the United Kingdom53 84 85 while others were from France,75 Spain,73 Canada,90 South Africa51 and Taiwan.70 86

Effects on adults

Four studies found that cigarette price increases had a greater effect in those on lower incomes.59 66 70 90 Two UK studies found that effects on smoking were greater among those in manual occupations than those in professional occupations84 85 but a later UK study found no evidence of differential effects by occupation.53 There was also some evidence to suggest that those with higher levels of education may be more sensitive to price.70 77 86 We found no clear evidence for differential effects by gender or ethnicity.

Effects on young people

All 20 studies restricted to adolescents or college students found that these groups were sensitive to price and concluded that increasing the price of tobacco products would reduce youth smoking.52 56 57 60 61 64 68 69 72 76 78–83 88 89 91 92 The only study comparing children within different age groups found that those aged 17 or 18-years-old were more sensitive to price increases than those aged between 13 and 16-years-old.68 Four studies found that boys aged 13–18 were more sensitive to price than girls.76 88 89 91 All three studies which examined effects by ethnicity found that black or Hispanic adolescents were more affected by price increases than their white counterparts.68 88 92 No studies provided evidence about possible differential effects by parental income, occupation or educational level.

Multifaceted interventions

Five studies assessed the effects of combinations of interventions, mainly the combined effects of different anti-tobacco laws.93–97 Studies were published between 1997 and 2004. Two studies examined the impact of the 1976 National Tobacco Control Act in Finland.94 95 One study assessed the impact of French legislation including restrictions on smoking in the workplace, advertising restrictions, health warnings on tobacco products and restrictions on sales to minors. This study involved a survey of hospital employees, mainly female nurses and healthcare workers.93 One study assessed smoking restrictions in Californian schools as part of an independent evaluation of the Californian Tobacco Control Prevention and Education Program.97 The fifth study assessed the effects of price increases and tobacco control legislation in Canada.96 The effects of the components of these interventions were not assessed separately within the studies and we therefore classified them as multifaceted interventions in our analysis.

One study found that the introduction of a tobacco control act in Finland reduced the rate of smoking initiation among young people.94 We found no evidence of differential effects by gender (interventions in all four studies were effective for both men and women)93–95 97 or ethnicity (one study).97 No studies provided evidence about possible differential effects by income, occupation or educational level.

DISCUSSION

Principal findings

This review has systematically and comprehensively applied an “equity lens” to tobacco control interventions, re-examining the available evidence about the impact of policy measures and other population-level interventions in order to assess their role in tackling health inequalities.101

The literature is international, with over half of the studies having been conducted in the United States and just six in the United Kingdom, and is dominated by econometric analyses (half of the included studies) modelling the effects of the prices of tobacco products.

Overall, we found no strong evidence that restrictions in workplaces and public places are more effective in reducing smoking in more advantaged groups, although smoking behaviour and attitudes may be more favourably affected among those in higher occupational grades.

We found evidence from single studies that smoking restrictions in schools may be more effective in girls and in younger schoolchildren, but there was an absence of evidence with respect to other possible differential effects. We found more, better-quality evidence on the differential effects of restrictions on sales to minors: restrictions seem to be more effective in girls and in younger schoolchildren, and one study of a combined education and enforcement intervention found restrictions on sales to minors to be more effective in white than non-white groups. For health warnings on tobacco products and restrictions on tobacco advertising, the lack of robust studies makes firm conclusions difficult. The effects of health warnings do not appear to be subject to a sociodemographic gradient, but their effects have not been examined with respect to income, occupation or ethnicity and the evidence with respect to educational level, gender and age is not convincing. The effects of advertising bans also show no differential by gender or age, but the evidence is not strong and other potential gradients have not been examined in primary studies.

The balance of econometric evidence suggests that increasing the price of tobacco is more effective in reducing smoking in lower-income adults and those in manual occupations. There was also some evidence to suggest that smokers with higher levels of education may be more responsive to price, although this evidence was limited to somewhat specific study populations (men in Taiwan and pregnant women in the United States, whose response to pricing may be confounded by knowledge of the risks of smoking during pregnancy). The evidence with respect to differential effects by gender, ethnicity or age is not consistent. Although we found fewer studies assessing the effects of pricing in children, it appears that boys, non-white children and perhaps also older children may be more price-sensitive. We found no evidence as to how the effects on children varied by household income.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

We made extensive attempts to obtain both published and unpublished studies and to include a wide range of study designs in order to avoid overlooking evidence from weaker studies which to date have mainly been excluded from systematic reviews. However, it remains possible that we have not identified all relevant tobacco control intervention programmes or policies, given that some may not have been formally evaluated or reported.

One difficulty in dealing with a diverse public health evidence base is the need to incorporate considerable heterogeneity in intervention, study design and appropriateness of that design, study quality and study outcomes (in this case, “hard” behavioural and “softer” attitudinal outcomes). The stratification of outcomes by social group adds another level of complexity. To manage this we developed a novel graphical method, the “harvest plot”, to synthesise and display the balance of evidence to support competing hypotheses about possible social gradients in the effects of the interventions. This methodological development is a considerable strength of the review and may be of use to others reviewing the public health literature; the rationale for this method and its advantages and disadvantages are discussed in a separate methodological paper.100

Strengths and weaknesses of the available evidence

There are undoubted limitations in the evidence base, most notably a lack of prospective evaluations. A particular challenge is the difficulty of attributing outcomes solely to the intervention in question. Authors often did not report co-interventions or describe other contextual factors that might have influenced the success of the intervention. Although we excluded studies focusing solely on individual-level interventions, population tobacco control policies rarely exist in isolation and several studies included individual-level interventions such as smoking cessation classes alongside workplace smoking bans. A decision to intervene at one level (policy) could be adversely affected by actions at other levels; alternatively, there could be a synergistic effect.102 Contextual information would also help policy-makers and practitioners better understand how successful interventions could be implemented.103

The completeness and clarity of reporting in primary studies in this field would also be improved by the inclusion of more methodological details (such as study design, sampling, population characteristics, data collection tools, methods of analysis and attrition rates), by assessing the differential impact of interventions across different sociodemographic groups and by reporting data on changes in smoking behaviour rather than relying on changes in attitudes which may be a poor proxy for behaviour change. One of the more obvious limitations is the absence of qualitative research on population-level tobacco interventions and their effects on social inequalities in smoking. Although we sought such studies, we found only one. New qualitative research will also have an important part to play in identifying intended and unintended effects of policy interventions and barriers to change before implementation.102

Implications for policy and practice

The current EU green paper on policy options for progressing towards a “smoke-free Europe” notes that smoke-free policies may reduce socioeconomic inequalities in health and calls for qualitative and quantitative evidence on the impacts of such policies.104 Our systematic review addresses this call, contributes a step towards understanding the interventions that are effective for different social groups and may inform decisions about tackling social inequalities in smoking.

The most compelling evidence of a social gradient in effectiveness which favours the least well off is for the price of tobacco products; although we also found some evidence to suggest an apparently greater effect of price on those with higher levels of education, such evidence is limited and requires further investigation. Increasing the price of tobacco is therefore the population-level intervention for which we found the strongest evidence as a measure for reducing smoking-related inequalities in health. However, the effects of increasing tobacco taxation may be undermined by tax-evasion or tax-avoidance measures such as smuggling and cross-border shopping.105 The Acheson inquiry106 and other commentators107 108 have also raised concern about the long-term effect of price rises on disadvantaged households, where smokers are more likely to be nicotine-dependent and for whom living in hardship is the primary deterrent to quitting. Any further increase in tobacco taxation would therefore require extra measures to support cessation among low-income households.

None the less, we found more evidence to support increasing the price of tobacco products than to support other more visible interventions such as health warnings and advertising restrictions, whose differential effects appear under-explored. However, although interventions such as health warnings and advertising restrictions may not in themselves affect inequalities, they may be important as part of a wider tobacco control strategy, if they help to elicit public support for other measures.109

The evidence on restrictions on sales to minors suggests that these may be effective in deterring younger smokers, though their effectiveness depends on enforcement as unenforced voluntary agreements with retailers are less effective in reducing sales.105 Pricing may be less effective among some groups of younger smokers, perhaps because they may obtain their cigarettes from non-commercial sources.105 Among younger smokers restrictions in schools (which affect consumption) and health warnings (which affect attitudes to smoking) may therefore be more productive. Appropriately enforced restrictions on sales to minors may offer the greatest promise as part of a strategy for tackling inequalities. While combinations of interventions are also likely to be an important part of the policy armoury—including restrictions in schools (which affect consumption) and health warnings (which affect attitudes to smoking)—the differential effects of such combinations largely remain an area for further research.

It is also important to identify policies that have the potential to increase inequalities. Our findings are encouraging, as we found little evidence of adverse effects in this regard. One exception was workplace restrictions, which may be more effective among higher occupational grades. This suggests that the implementation of such policies should be accompanied by measures to promote adherence across all occupational grades. This supports the case for legislating for mandatory workplace bans, rather than relying on willing employers to introduce voluntary bans.

Unanswered questions and future research

We have identified many gaps in the evidence base on interventions to reduce social inequalities in smoking. In particular, we know little about the differential effects of most categories of intervention by income, gender or ethnicity. For tobacco pricing—a relatively well researched field—we also need to know more about effects on adolescents from lower-income households and on young people in general, and on lower-income adults who are likely to be nicotine-dependent. For restrictions on sales to minors—another relatively well researched field—it is unclear whether differential effects vary between interventions that involve education, enforcement or both. Where population-level studies are carried out there could be greater use of pre-planned subgroup analyses, specifically to shed light on effects on inequalities, but there also remains a need for robust evaluations of targeted interventions (even accepting that these may not provide evidence about effects on inequalities). Perhaps the most important observation is that much of the existing evidence derives from the United States. The greatest research priority should therefore be to develop relevant evidence for other country contexts with a focus on behavioural outcomes. The introduction of new population-level tobacco control policies—such as the restrictions on smoking in public places now introduced in all the countries of the United Kingdom and elsewhere—provides such an opportunity.

What is already known on this subject

Reducing social inequalities in smoking and its health consequences is a public-health and political priority.

Little is known about the actual effects of measures to reduce health inequalities in general or about the differential impacts of tobacco control measures in particular.

It is possible that a strategy which successfully reduced smoking in the population overall might widen inequalities if its benefits were concentrated among the better-off.

What this study adds

This is the most comprehensive review to date of the potential effects on heath inequalities of population-level tobacco control interventions and makes an important contribution towards understanding the effects of interventions in different social groups.

In terms of reducing social inequalities in smoking, we found better evidence to support increasing the price of tobacco products than to support more visible interventions such as health warnings and advertising restrictions.

We found little evidence of policies that have the potential to increase inequalities. In particular, we found no strong evidence that smoking restrictions in workplaces and public places are more effective among more advantaged groups.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Godfrey, Hilary Graham, Gerard Hastings, Betsy Kristjansson, Johan Mackenbach, Alan Marsh, Steve Platt, George Thomson and Peter Craig for their comments and suggestions on drafts of the study protocol and reports; James Coates for the design and construction of the Access database for the review; and Caroline Main for assistance with screening search results, assessment of studies for inclusion and design of the data extraction form.

Footnotes

Funding: This review was funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme (PRP) (reference number RDD/030/077). This work was undertaken by all the authors, who received funding from Department of Health Policy Research Programme. The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. MP was funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive Health Department. DO was funded by a Medical Research Council fellowship. The authors’ work was independent of the funders.

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: DO, AJS, MP and MW designed the study. DO designed and populated the harvest plot. KM conducted the literature searches. ST, DF and GW screened the search results, assessed studies for inclusion, conducted data extraction and quality assessment and synthesised the data. ST, DF, GW, MP and AJS checked data extraction and quality assessment. All authors contributed to the interpretation of findings for research and policy. ST wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all other authors contributed to its critical revision and approved the final version. ST is guarantor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leon D, Walt G, Gilson L. International perspectives on health inequalities and policy. BMJ 2001;322:591–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tugwell P, Kristjansson B. Moving from description to action: challenges in researching socio-economic inequalities in health. Can J Public Health 2004;95:85–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macintyre S, Chalmers I, Horton R, et al. Using evidence to inform health policy: case study. BMJ 2001;322:222–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, et al. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet 2006;368:367–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health The NHS cancer plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Stationery Office, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarvis JD, Wardle J. Social patterning of individual health behaviours: the case of cigarette smoking. Marmot M, Wilkinson R G, eds. Social determinants of health. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006:224–37 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health Delivering the NHS Cancer Plan. Cancer prevention: smoking. London: DH, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauld L, Judge K, Platt S. Assessing the impact of smoking cessation services on reducing health inequalities in England: observational study. Tob Control 2007;16:400–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Levelling up. Part II: European strategies to tackle social inequities in health: a discussion paper on European strategies for tackling social inequities in health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, 2006; Available from http://www.euro.who.int/document/e89384.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogilvie D, Petticrew M. Reducing social inequalities in smoking: can evidence inform policy? A pilot study. Tob Control 2004;13:129–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briss P, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to community preventive services—methods. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(1S):35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas H. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Hamilton, Ontario: Effective Public Health Practice Project, 2003; Available from http://www.myhamilton.ca/NR/rdonlyres/04A24EBE-2C46-411D-AEBA-95A60FDEF5CA/0/QualityTool2003.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans T, Brown H. Road traffic crashes: operationalizing equity in the context of health sector reform. Inj Control Saf Promot 2003;10:11–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker D, Conner H, Waranch H, et al. The impact of a total ban on smoking in the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. JAMA 1989;262:799–802 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borland R, Owen N, Hocking B. Changes in smoking behaviour after a total workplace smoking ban. Aust J Public Health 1991;15:130–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawley HH, Morrison J, Carrol S. The effect of differently worded no-smoking signs on smoking behavior. Int J Addict 1981;16:1467–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donchin M, Baras M. A ‘smoke-free’ hospital in Israel—a possible mission. Prev Med 2004;39:589–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heloma A, Jaakkola MS. Four-year follow-up of smoke exposure, attitudes and smoking behaviour following enactment of Finland’s national smoke-free work-place law. Addiction 2003;98:1111–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassab J, Morgan G, Williams E, et al. Smoking prevalence and attitudes of Gwynedd Health Authority staff towards passive smoking and the authority’s non-smoking policy. Health Trends 1992;24:8–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Offord KP, Hurt RD, Berge KG, et al. Effects of the implementation of a smoking free policy in a medical center. Chest 1992;102:1531–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olive KE, Ballard JA. Changes in employee smoking behavior after implementation of restrictive smoking policies. South Med J 1996;89:699–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parry O, Platt S. Smokers at risk: Implications of an institutionally bordered risk- reduced environment. Health Place 2000;6:117–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorensen G, Rigotti NA, Rosen A. Effects of a worksite non-smoking policy: evidence for increased cessation. Am J Public Health 1991;81:202–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorensen G, Beder B, Prible CR, et al. Reducing smoking at the workplace: implementing a smoking ban and hypnotherapy. J Occup Environ Med 1995;37:453–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stillman FA, Becker DM, Swank RT, et al. Ending smoking at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions: an evaluation of smoking prevalence and indoor air pollution. JAMA 1990;264:1565–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang H, Cowling DW, Lloyd JC, et al. Changes of attitudes and patronage behaviors in response to a smoke-free bar law. Am J Public Health 2003;93:611–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waa A, Gillespie J. Reducing exposure to second hand smoke: changes associated with the implementation of the amended New Zealand Smoke-free Environments Act 1990: 2003–2005. Wellington: HSC Research and Evaluation Unit, 2005:25 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar R, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. School tobacco control policies related to students’ smoking and attitudes toward smoking: national survey results, 1999–2000. Health Educ Behav 2005;32:780–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thrush D, Fife-Schaw C, Breakwell G. Evaluations of interventions to reduce smoking. Swiss J Psychol 1999;58:85–100 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinidad DR, Gilpin EA, Pierce JP. Compliance and support for smoke-free school policies. Health Educ Res 2005;20:466–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altman DG, Wheelis AY, McFarlane M, et al. The relationship between tobacco access and use among adolescents: a four community study. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:759–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forster JL, Murray DM, Wolfson M, et al. The effects of community policies to reduce youth access to tobacco. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1193–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinds MW. Impact of a local ordinance banning tobacco sales to minors. Public Health Rep 1992;107:355–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jason LA, Pokorny SB, Schoeny ME. Evaluating the effects of enforcements and fines on youth smoking. Crit Public Health 2003;13:33–45 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laugesen M, Scragg R. Changes in cigarette purchasing by fourth form students in New Zealand 1992–1997. N Z Med J 1999;112:379–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livingood WC, Woodhouse CD, Sayre JJ, et al. Impact study of tobacco possession law enforcement in Florida. Health Educ Behav 2001;28:733–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimpela AH, Rainio SU. The effectiveness of tobacco sales ban to minors: the case of Finland. Tob Control 2004;13:167–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel M, Biener L, Rigotti NA. The effect of local tobacco sales laws on adolescent smoking initiation. Prev Med 1999;29:334–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staff M, March L, Brnabic A, et al. Can non-prosecutory enforcement of public health legislation reduce smoking among high school students? Aust N Z J Public Health 1998;22:332–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staff M, Bennett CM, Angel P. Is restricting tobacco sales the answer to adolescent smoking? Prev Med 2003;37:529–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundh M, Hagquist C. Effects of a minimum-age tobacco law—Swedish experience. Drug Educ Prev Policy 2005;12:501–510 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomson CC, Gokhale M, Biener L, et al. Statewide evaluation of youth access ordinances in practice: effects of the implementation of community-level regulations in Massachusetts. J Public Health Manag Pract 2004;10:481–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tutt D, Bauer L, Edwards C, et al. Reducing adolescent smoking rates. Maintaining high retail compliance results in substantial improvements. Health Promot J Austr 2000;10:20–4 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fielding R, Chee YY, Choi KM, et al. Declines in tobacco brand recognition and ever-smoking rates among young children following restrictions on tobacco advertisements in Hong Kong. J Public Health 2004;26:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joossens L. The effectiveness of banning advertising for tobacco products. Brussels: Union Internationale Contre le Cancer, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borland R, Hill D. Initial impact of the new Australian tobacco health warnings on knowledge and beliefs. Tob Control 1997;6:317–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gospodinov N, Irvine IJ. Global health warnings on tobacco packaging: evidence from the Canadian experiment. Top Econ Anal Pol 2004;4:1–21 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koval JJ, Aubut JA, Pederson LL, et al. The potential effectiveness of warning labels on cigarette packages: the perceptions of young adult Canadians. Can J Public Health 2005;96:353–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson TN, Killen JD. Do cigarette warning labels reduce smoking?: paradoxical effects among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151:267–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willemsen MC. The new EU cigarette health warnings benefit smokers who want to quit the habit: results from the Dutch Continuous Survey of Smoking Habits. Eur J Public Health 2005;15:389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berg GD, Kaempfer WH. Cigarette demand and tax policy for race groups in South Africa. Appl Econ 2001;33:1167–73 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bishai DM, Mercer D, Tapales A. Can government policies help adolescents avoid risky behavior? Prev Med 2005;40:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borren P, Sutton M. Are increases in cigarette taxation regressive? Health Econ 1992;1:245–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chaloupka F. Clean indoor air laws, addiction, and cigarette smoking. Appl Econ 1992;24:193–205 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaloupka FJ. Rational addictive behavior and cigarette smoking. J Polit Econ 1991;99:722–42 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaloupka FJ, Tauras JA, Grossman M. Public policy and youth smokeless tobacco use. South Econ J 1997;64:503–16 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaloupka FJ, Grossman M. Price, tobacco control policies and youth smoking. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1996. Working Paper 5740 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaloupka FJ, Wechsler H. Price, tobacco control policies and smoking among young adults. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1995. Working Paper 5012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Colman G, Remler DK. Vertical equity consequences of very high cigarette tax increases: if the poor are the ones smoking, how could cigarette tax Increases be progressive? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2004. Working Papers 10906. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Czart C, Pacula RL, Chaloupka FJ, et al. The impact of prices and control policies on cigarette smoking among college students. Contemp Econ Policy 2001;19:135–49 [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeCicca P, Kenkel D, Mathios A. Putting out the fires: will higher taxes reduce the onset of youth smoking? J Polit Econ 2002;110:144–69 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Foulds J, et al. Cigar use before and after a cigarette excise tax increase in New Jersey. Addic Behaviors 2004;29:1799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding A. Youth are more sensitive to price changes in cigarettes than adults. Yale J Bio Med 2003;76:115–24 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emery S, White MM, Pierce JP. Does cigarette price influence adolescent experimentation? J Health Econ 2001;20:261–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Evans W, Farrelly M. The compensating behavior of smokers: taxes, tar, and nicotine. Rand J Econ 1998;29:578–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Farrelly MC, Bray JW, Pechacek T, et al. Response by adults to increases in cigarette prices by sociodemographic characteristics. South Econ J 2001;68:156–65 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goel RK, Nelson MA. Tobacco policy and tobacco use: differences across tobacco types, gender and age. Appl Econ 2005;37:765–71 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gruber J. Youth smoking in the US: prices and policies. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2000. Working Paper 8962 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katzman B, Markowitz S, McGeary KA. The impact of lending, borrowing, and anti-smoking policies on cigarette consumption by teens. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2002. Working Paper 8844 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee JM, Hwang TC, Ye CY, et al. The effect of cigarette price increase on the cigarette consumption in Taiwan: evidence from the National Health Interview Surveys on cigarette consumption. BMC Public Health 2004;4:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lewit EM, Coate D. The potential for using excise taxes to reduce smoking. J Health Econ 1982;1:121–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liang L, Chaloupka FJ. Differential effects of cigarette price on youth smoking intensity. Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4:109–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lopez Nicolas A. How important are tobacco prices in the propensity to start and quit smoking? An analysis of smoking histories from the Spanish national health survey. Health Econ 2002;11:521–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ohsfeldt RL, Boyle RG, Capilouto EL. Tobacco taxes, smoking restrictions, and tobacco use. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1998. Working Paper 6486 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peretti-Watel P. Pricing policy and some other predictors of smoking behaviours: an analysis of French retrospective data. Int J Drug Policy 2005;16:19–26 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ringel JS, Wasserman J, Andreyeva T. Effects of public policy on adolescents’ cigar use: evidence from the National Youth Tobacco Survey. Am J Public Health 2005;95:995–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ringel JS, Evans WN. Cigarette taxes and smoking during pregnancy. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1851–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ross H, Chaloupka FJ. The effect of public policies and prices on youth smoking. South Econ Journal 2004;70:796–815 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tauras JA. Public policy and smoking cessation among young adults in the United States. Health Policy 2004;68:321–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tauras JA. Can public policy deter smoking escalation among young adults? J Policy Anal Manage 2005;24:771–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ. Price, clean indoor air laws, and cigarette smoking: evidence from longitudinal data for young adults. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1999. Working Paper 6937 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tauras JA, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Effects of price and access laws on teenage smoking initiation: a national longitudinal analysis. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2001. Working Paper 8331 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thomson CC, Fisher LB, Winickoff JP, et al. State tobacco excise taxes and adolescent smoking behaviors in the United States. J Public Health Manag Practice 2004;10:490–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Townsend J, Roderick P, Cooper J. Cigarette smoking by socioeconomic group, sex, and age: effects of price, income, and health publicity. BMJ 1994;309:923–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Townsend JL. Cigarette tax, economic welfare, and social class patterns of smoking. Appl Econ 1987;19:355–65 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tsai YW, Yang CL, Chen CS, et al. The effect of Taiwan’s tax-induced increases in cigarette prices on brand-switching and the consumption of cigarettes. Health Econ 2005;14:627–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wasserman J, Manning WG, Newhouse JP, et al. The effects of excise taxes and regulations on cigarette smoking. J Health Econ 1991;10:43–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chaloupka FJ, Pacula RL. Sex and race differences in young people’s responsiveness to price and tobacco control policies. Tob Control 1999;8:373–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Glied S. Youth tobacco control: reconciling theory and empirical evidence. J Health Econ 2002;21:117–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gruber J, Sen A, Stabile M. Estimating price elasticities when there is smuggling: the sensitivity of smoking to price in Canada. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2002. Working Paper 8962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lewit EM, Hyland A, Kerrebrock N, et al. Price, public policy, and smoking in young people. Tob Control 1997;6:S17–S24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nonnemaker JM. The impact of state excise taxes, school smoking policies, state tobacco control policies and peers on adolescent smoking [dissertation].Minneapolis, MI: University of Minnesota, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cooreman J, Mesbah H, Leynaert B, et al. Evaluation of the impact of a smoking ban in a large Paris hospital. Sem Hop 1997;73:317–23 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Helakorpi S, Martelin T, Torppa J, et al. Did Finland’s tobacco control act of 1976 have an impact on ever smoking? An examination based on male and female cohort trends. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:649–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Heloma A, Nurminen M, Reijula K, et al. Smoking prevalence, smoking-related lung diseases, and national tobacco control legislation. Chest 2004;126:1825–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stephens T, Pederson LL, Koval JJ, et al. Comprehensive tobacco control policies and the smoking behaviour of Canadian adults. Tob Control 2001;10:317–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Howard KA, et al. Attitudes toward anti-tobacco policy among California youth: associations with smoking status, psychosocial variables and advocacy actions. Health Educ Res 1999;14:751–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, et al. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7:209–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dixon-Woods M, Shaw RL, Agarwal A, et al. The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:223–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ogilvie D, Fayter D, Petticrew M, et al. The harvest plot: a method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Giskes K, Kunst A, Ariza C, et al. Applying an equity lens to tobacco-control policies and their uptake in six western-European countries. J Public Health Policy 2007;28:261–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Campbell NC, Murray E, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 2007;334:455–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arai L, Roen K, Roberts H, et al. It might work in Oklahoma but will it work in Oakhampton? Context and implementation in the effectiveness literature on domestic smoke detectors. Inj Prev 2005;11:148–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General Towards a Europe free from tobacco smoke: policy options at EU level. Brussels: European Commission, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ogilvie D, Gruer L, Haw S. Young people’s access to tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. BMJ 2005;331:393–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health report. London: Stationery Office, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 107.Graham H. Promoting health against inequality: using research to identify targets for intervention—a case study of women and smoking. Health Educ J 1998;57:292–302 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Marsh A. Tax and spend: a policy to help poor smokers. Tob Control 1997;6:5–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kunst A, Giskes K, Mackenbach J. Socio-economic inequalities in smoking in the European Union. Applying an equity lens to tobacco control policies. Rotterdam: Erasmus University; 2004; Available from http://www.ensp.org/files/socio.pdf [Google Scholar]