Abstract

Macrocyclic aminoacyl-AMP analogs have been developed to inhibit non-ribosomal peptide synthetase amino acid adenylation domains selectively by mimicking a cisoid ligand binding conformation observed in crystal structures. In contrast, these macrocycles do not inhibit aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, which are mechanistically closely related but bind their ligands in a distinct transoid conformation. The macrocycles contain a two- or three-carbon linker between Cβ of the amino acid moiety and C8 of the adenine ring and a sulfamate in place of the phosphate group. These compounds are potent inhibitors of the cysteine adenylation domain activity of the yersiniabactin siderophore synthetase HMWP2 and, unlike the corresponding linear aminoacyl-AMP analogs, do not inhibit protein translation in vitro. Selective small molecule inhibitors of non-ribosomal peptide synthesis should provide a powerful means to study the biological functions of non-ribosomal peptide natural products and a potential avenue to develop novel antibiotics.

Recent evidence suggests that natural products are much more than simply agents of “microbial warfare” and actually play critical roles in bacterial pathogenesis and communication.1 In particular, non-ribosomal peptide (NRP) natural products have been identified as key players in bacterial iron uptake,2 biofilm formation,3 and commensalism.4 Thus, small molecule inhibition of NRP biosynthesis would provide a powerful means to study the biological roles of these natural products and a potential avenue to develop novel antibiotics. Detailed mechanistic insights into NRP biosynthesis,5 developed primarily from the perspectives of fundamental interest and engineered biosynthesis, can be leveraged to design such inhibitors. Along these lines, we recently reported a mechanism-based inhibitor of NRP siderophore biosynthesis, salicyl-AMS (5′-O-[N-salicylsulfamoyl]adenosine).6 This compound targets salicylate adenylation enzymes by mimicking a key salicyl adenylate (salicyl-AMP) reaction intermediate through replacement of the reactive phosphate group with a stable sulfamate moiety. Related inhibitor design strategies have also been extended to other aryl acid adenylation enzymes that have no human homologs.7 However, application of this strategy to more widely distributed amino acid adenylation domains is complicated by a major selectivity problem: aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, which are used ubiquitously in ribosomal protein translation, catalyze nearly identical reactions (Figure 1a). Thus, simple aminoacyl-AMP analogs inhibit both classes of enzymes,8,9 making them unsuitable for probing NRP function or as antibiotics. Herein, we report a solution to this problem using macrocyclic aminoacyl-AMP analogs (2a, 2b) that exploit pronounced structural differences between these two protein classes to inhibit an amino acid adenylation domain selectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Reactions catalyzed by amino acid adenylation domains during NRP biosynthesis (PCP-SH nucleophile) and by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases during protein translation (tRNA-OH nucleophile). PCP = peptidyl carrier protein. (b) Cisoid conformation of phenylalanine and AMP ligands in a phenylalanine adenylation domain active site (PheA; PDB 1AMU). (c) Transoid conformation of a Phe-AMP analog in a phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase active site (PheRS; PDB 1B7Y). Adenine-C8-to-phenylalanine-Cβ distances are indicated (gray).

To design inhibitors that selectively target NRP synthetase amino acid adenylation domains, we compared the reported ligand-bound crystal structures of a phenylalanine adenylation domain (PheA) and a phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (PheRS).10 These enzymes catalyze analogous reactions involving adenylation of phenylalanine to form a phenylalanyl-AMP intermediate followed by transesterification to a peptidyl carrier protein thiol or tRNA hydroxyl respectively (Figure 1a). However, these proteins have unrelated folds and bind their ligands in distinct conformations.11 In the PheA structure, phenylalanine and AMP are bound in an overall “cisoid” conformation (Figure 1b). Examination of closely related aryl acid adenylation enzyme, fatty acyl-CoA ligase, and luciferase structures suggests that this cisoid ligand conformation is conserved across this family.11,12 In contrast, in PheRS, a phenylalanyl-AMP analog is bound in a “transoid” conformation (Figure 1c). Examination of all available ligand-bound aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase structures confirmed transoid ligand conformations in all cases.11 Based on this analysis, we postulated that non-hydrolyzable aminoacyl-AMP analogs in which the cisoid conformation is promoted or enforced would inhibit amino acid adenylation domains selectively, without inhibiting the corresponding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.

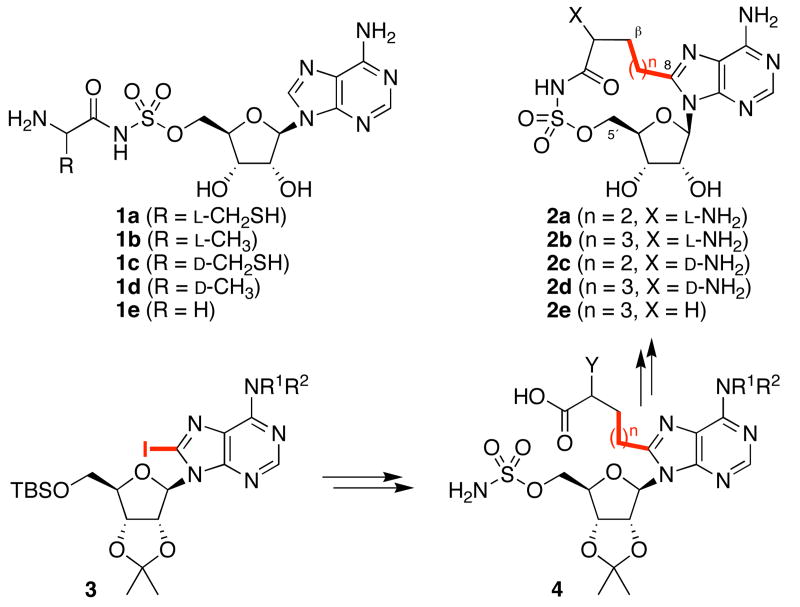

Further examination of the PheA structure revealed an unobstructed 4.1 Å space between C8 of adenine and Cβ of phenylalanine (Figure 1b), suggesting that a two- or three-atom linker might be used to enforce the desired cisoid pharmacophoric conformation in a macrocyclic inhibitor. Such compounds would not be able to adopt the transoid conformation required to bind the corresponding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Thus, we designed macrocycles 2a–e (Figure 2) as constrained analogs of alanyl-AMP. We envisioned that such compounds might inhibit other amino acid adenylation domains, such as the cysteine adenylation domain in the Yersinia pestis siderophore biosynthesis enzyme HMWP2,13 provided that the missing β sidechain could be compensated by a reduced entropic cost of binding and/or new favorable binding interactions.14

Figure 2.

Structures of adenylation domain inhibitors and general synthetic approach to macrocycles.11 (R1, R2 = Boc or H; Y = NHBoc or H).

After exploring several synthetic approaches, we arrived at macrocycles 2a–e using the general strategy outlined in Figure 2.11 Briefly, 8-iodoadenosine 3 is functionalized at the adenine C8-position via cross coupling reactions, then 5′-O-sulfamoylated. Macrolactamization of 4 and global deprotection provides macrocycles 2. Linear aminoacyl-AMS analogs 1a–e were also synthesized for comparison.

With this battery of compounds in hand, we set out to test their activities against the cysteine adenylation domain of yersiniabactin synthetase HMWP2. Gratifyingly, both macrocycles 2a and 2b were potent inhibitors in a cysteine adenylation assay (Table 1).11 Notably, the two-carbon-linked macrocycle 2a was slightly more potent than l-alanyl-AMS (1b) and nearly as potent as the “cognate” inhibitor l-cysteyl-AMS (1a). In contrast, macrocycles 2c and 2d, which are analogs of d-alanyl-AMS (1d), and desamino macrocycle 2e were all poor inhibitors.

Table 1.

Inhibition of a Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase Amino Acid Adenylation Domain and of in vitro Translation.11

| entry | compound | Kiapp (HMWP2, μM)a | IC50 (in vitro translation, μM)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a (l-Cys-AMS) | 0.24 | ± 0.02c | 15.5 | ± 0.3 |

| 2 | 1b (l-Ala-AMS) | 2.5 | ± 0.2 | 0.16 | ± 0.03 |

| 3 | 1c (d-Cys-AMS) | 0.37 | ± 0.02 | n.d. | |

| 4 | 1d (d-Ala-AMS) | 34 | ± 3 | n.d. | |

| 5 | 1e (Gly-AMS) | 16 | ± 5 | n.d. | |

| 6 | 2a (cyclo8C2β-l-Ala-AMS) | 1.7 | ± 0.1d | >250 | |

| 7 | 2b (cyclo8C3β-l-Ala-AMS) | 5.4 | ± 0.8e | >250 | |

| 8 | 2c (cyclo8C2β-d-Ala-AMS) | 150 | ± 60 | n.d. | |

| 9 | 2d (cyclo8C3β-d-Ala-AMS) | 400 | ± 100 | n.d. | |

| 10 | 2e (cyclo8C3β-propionyl-AMS) | 210 | ± 30 | n.d. | |

30 nM HMWP21–1491-His6, 1 mM [32P]-PPi, 3 mM ATP, 3 mM l-cysteine.

n.d. = not determined.

KiCys = 0.101 ± 0.005 μM; KiATP = 0.062 ± 0.002 μM.11

KiCys = 0.27 ± 0.03 μM; KiATP = 0.179 ± 0.005 μM.

KiCys = 0.92 ± 0.06 μM; KiATP = 0.57 ± 0.01 μM.

To test our hypothesis that the macrocyclic constraints would prevent these compounds from inhibiting aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, we used an in vitro translation assay containing all 20 of these enzymes.11 While both l-cysteyl-AMS (1a) and l-alanyl-AMS (1b) potently inhibited protein translation, presumably by targeting the corresponding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, we were pleased to find that macrocycles 2a and 2b showed no inhibitory activity at up to 250 μM concentration. Thus, the macrocyclic structure provides exquisite selectivity for an amino acid adenylation domain over aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.

In summary, we have developed potent, highly selective macrocyclic inhibitors of an amino acid adenylation domain that do not inhibit aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. We have exploited distinct ligand binding conformations to distinguish between these mechanistically related enzymes. Further studies to explore the scope of adenylation domain inhibition and the cellular activity of these compounds and analogs thereof are ongoing. Given the high structural homology among amino acid adenylation domains,11,12d it will be of interest to determine whether such compounds can inhibit other domains, thereby providing a broad spectrum means to inhibit NRP biosynthetic pathways and to probe the biological and therapeutic implications thereof. Broad inhibitors might also synergistically inhibit multiple adenylation domains in an individual pathway to afford increased potency15 and decreased susceptibility to resistance conferring mutations.16

Supplementary Material

Detailed experimental procedures and analytical data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. George Sukenick, Hui Fang, and Sylvi Rusli for mass spectral analyses. L.E.N.Q. is a Stavros S. Niarchos Foundation Scholar. D.S.T. is a NYSTAR Watson Investigator. Financial support from the NIH (R21 AI063384, P01 AI056293), William Randolph Hearst Foundation, William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, and MSKCC Experimental Therapeutics Center is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Keller L, Surette MG. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:249–258. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratledge C, Dover LG. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:881–941. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Visca P, Imperi F, Lamont IL. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stein T. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:845–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Roongsawang N, Hase Ki, Haruki M, Imanaka T, Morikawa M, Kanaya S. Chem Biol. 2003;10:869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hofemeister J, Conrad B, Adler B, Hofemeister B, Feesche J, Kucheryava N, Steinborn G, Franke P, Grammel N, Zwintscher A, Leenders F, Hitzeroth G, Vater J. Mol Genet Genom. 2004;272:363–378. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1056-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Raaijmakers JM, de Bruijn I, de Kock MJD. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006;19:699–710. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Freeman R, Geier H, Weigel KM, Do J, Ford TE, Cangelosi GA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7554–7558. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01633-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nougayrede JP, Homburg S, Taieb F, Boury M, Brzuszkiewicz E, Gottschalk G, Buchrieser C, Hacker J, Dobrindt U, Oswald E. Science. 2006;313:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1127059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreras JA, Ryu JS, Di Lello F, Tan DS, Quadri LEN. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:29–32. doi: 10.1038/nchembio706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Somu RV, Boshoff H, Qiao C, Bennett EM, Barry CE, III, Aldrich CC. J Med Chem. 2006;49:31–34. doi: 10.1021/jm051060o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miethke M, Bisseret P, Beckering CL, Vignard D, Eustache J, Marahiel MA. FEBS J. 2006;273:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Callahan BP, Lomino JV, Wolfenden R. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:3802–3805. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueda H, Shoku Y, Hayashi N, Mitsunaga J, In Y, Doi M, Inoue M, Ishida T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1080:126–134. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90138-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marahiel first used aminoacyl-AMS to inhibit adenylation domains: Finking R, Neumueller A, Solsbacher J, Konz D, Kretzschmar G, Schweitzer M, Krumm T, Marahiel MA. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:903–906. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300666.Recently, Marahiel cleverly targeted a D-alanine-specific enzyme in bacteria: May JJ, Finking R, Wiegeshoff F, Weber TT, Bandur N, Koert U, Marahiel MA. FEBS J. 2005;272:2993–3003. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04700.x.

- 10.(a) Conti E, Stachelhaus T, Marahiel MA, Brick P. EMBO J. 1997;16:4174–4183. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reshetnikova L, Moor N, Lavrik O, Vassylyev DG. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:555–568. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.See Supporting Information for full details.

- 12.(a) May JJ, Kessler N, Marahiel MA, Stubbs MT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12120–12125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182156699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hisanaga Y, Ago H, Nakagawa N, Hamada K, Ida K, Yamamoto M, Hori T, Arii Y, Sugahara M, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S, Miyano M. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31717–31726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakatsu T, Ichiyama S, Hiratake J, Saldanha A, Kobashi N, Sakata K, Kato H. Nature. 2006;440:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature04542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See also: Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. Chem Biol. 1999;6:493–505. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80082-9.

- 13.Gehring AM, Mori I, Perry RD, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11637–11650. doi: 10.1021/bi9812571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For early examples, see: Thaisrivongs S, Blinn JR, Pals DT, Turner SR. J Med Chem. 1991;34:1276–1282. doi: 10.1021/jm00108a006.Weber AE, Halgren TA, Doyle JJ, Lynch RJ, Siegl PKS, Parsons WH, Greenlee WJ, Patchett AA. J Med Chem. 1991;34:2692–2701. doi: 10.1021/jm00113a005.Khan AR, Parrish JC, Fraser ME, Smith WW, Bartlett PA, James MNG. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16839–16845. doi: 10.1021/bi9821364.

- 15.A related effect was observed in our in vitro translation assay, with L-alanyl-AMS (1b) exhibiting ≈100-fold increased potency and a much higher Hill coefficient than L-cysteyl-AMS (1a), consistent with the 42 alanines versus 4 cysteines in the protein translated.11

- 16.Spratt BG. Science. 1994;264:388–393. doi: 10.1126/science.8153626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed experimental procedures and analytical data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.