Abstract

The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the immediate effects of a manual therapy technique called Inhibitive Distraction (ID) on active range of motion (AROM) for cervical flexion in patients with neck pain with or without concomitant headache. A secondary objective of this study was to see whether patient subgroups could be identified who might benefit more from ID by studying variables such as age, pain intensity, presence of headache, or pre-intervention AROM. We also looked at patients' ability to identify pre- to post-intervention changes in their ability to actively move through a range of motion. Forty subjects (mean age 34.7 years; range 16–48 years) referred to a physical therapy clinic due to discomfort in the neck region were randomly assigned to an experimental and a control group. We used the CROM goniometer to measure pre- and post-intervention cervical flexion AROM in the sagittal plane within a single treatment session. The between-group difference in AROM increase was not statistically significant at P<0.05 with a mean post-intervention increase in ROM of 2.4° (SD 6.2°) for the experimental group and 1.2° (SD 5.8°) for the placebo group. We were also unable to identify potential subgroups more likely to respond to ID, although a trend emerged for greater improvement in chronic patients with headaches, lower pain levels, and less pre-intervention AROM. In the experimental group and in both groups combined, subjects noting increased AROM indeed had a significantly greater increase in AROM than those subjects not noting improvement. In conclusion, this study did not confirm immediate effects of ID on cervical flexion AROM but did provide indications for potential subgroups likely to benefit from this technique. Recommendations are provided with regard to future research and clinical use of the technique studied.

Key Words: Cervical, Active Range of Motion, Inhibitive Distraction, Neck Pain, Pilot Study

Neck pain as well as headache types with a proposed cervical etiology or contribution are highly prevalent disorders. Douglass and Bope1 reported a point-prevalence for neck pain in the general population of 9%. They further noted a 1-month, 6-month, and lifetime prevalence of 10%, 54%, and 66%, respectively. In a cross-sectional population survey, Guez et al2 found an 18% prevalence for chronic neck pain (>6 months' duration). Headache types associated with cervical spine dysfunction include tension-type and cervicogenic headache, occipital neuralgia, and—to a lesser extent—migraine headaches3. Tension-type headache affects two-thirds of men and over 80% of women in developed countries4. For the general population, the prevalence of cervicogenic headache varies between 0.4% and 2.5%; in those with chronic headaches, prevalence may be as high as 15% to 20%5.

Neck pain and headache are not only highly prevalent but also frequent reasons for patients to seek medical or physical therapy (PT) care. In the United States, neck pain accounts for almost 1% of all primary care physician visits1, and cervical spine diagnoses were the reason for referral in 16% of 1,258 outpatient PT patients, second only to lumbar spine-related diagnoses, which accounted for 19% of referrals6. No data are available on the prevalence of headache as a cause for PT management; however, Boissonnault6 reported headache as co-morbidity in 22% of 2,433 patients presenting for outpatient physical and occupational therapy, and headaches are reportedly the leading cause for visits to a neurologist4.

Physical therapists place a diagnostic emphasis on identifying impairments that may be amenable to management with interventions within their scope of practice. In this context, impairments are defined as any loss or abnormality of body structure or of a physiological or psychological function7. Studies have shown a strong correlation between neck pain and restricted cervical flexion-extension mobility8,9, and limited motion may be the most relevant impairment associated with neck pain and headache of a proposed cervical etiology. Dvorák et al10 attributed cervical hypomobility to either a voluntary or reflexogenic muscular restraint caused by pain or a purely mechanical restraint caused by degeneration of the joint surfaces and ligaments. Corresponding to said degenerative process, Cantu and Grodin11 described a fibrotic process in connective tissue, whereby it shrinks progressively, caused by arthrokinematic dysfunction, poor posture, overuse, habit patterns, or structural or movement imbalances. They further suggested that in many cases the surrounding musculature maintains a hypertonic recruitment pattern long after the inducing injury has healed, potentially immobilizing joints by the surrounding muscle hypertonicity.

Myofascial trigger points (MTrP) in the cervical muscles constitute another potentially relevant muscle dysfunction leading to limited cervical spine mobility. These are defined as hyperirritable spots in skeletal muscle with a potential to give rise to characteristic referred pain, motor dysfunction, and autonomic phenomena12. Motor aspects of MTrPs may include disturbed motor function, muscle weakness as a result of motor inhibition, and—most importantly in the context of this study—muscle stiffness and restricted range of motion13. Trigger points in the head and neck region have been implicated in the reported headache and central sensitization in patients with tension-type headache. Their referral patterns correspond to the pain characteristics and distribution reported by patients with cervicogenic headache, occipital neuralgia, and migraine headache3. Studies have reported significantly greater numbers of active MTrPs in the suboccipital muscles of patients with tension-type headache and in patients with migraine headache when compared to asymptomatic controls14–16. Motor effects of these suboccipital MTrPs in the sense of muscle shortening may explain the increased forward head posture and decreased cervical AROM reported in patients with chronic tension-type headache or migraine headache as compared to asymptomatic controls14,16,17.

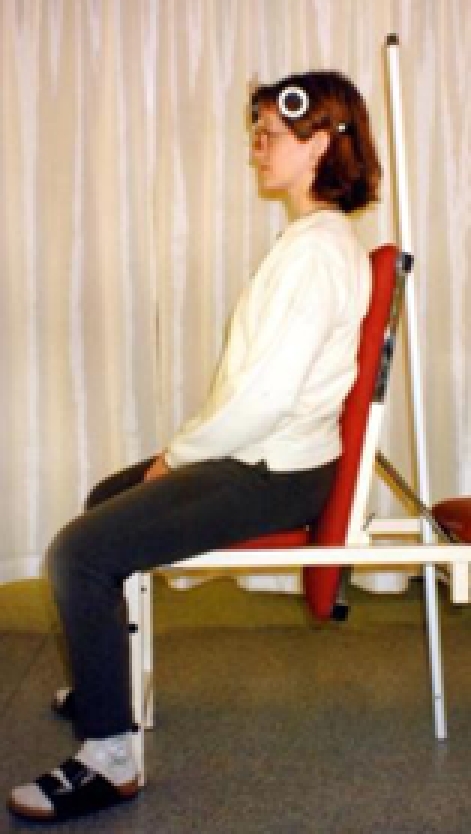

Relevant to the management of patients with neck pain and headache, Paris18 has described a technique called inhibitive distraction (ID) in which the therapist uses the fingertips of both hands to exert a sustained ventrocranial force on the occiput just caudal to the superior nuchal line (Figure 1). He proposed that this technique might inhibit the muscles inserting into the nuchal line and that it could be used to apply a distraction to the cervical spine structures. Paris18 did not claim this technique as his own, instead ascribing its origin to cranial osteopathy. Indeed, this technique has been described within various manual medicine disciplines under various names such as cranial base release, suboccipital release, and trigger point pressure release12,19–21. The proposed effects are mainly neurophysiological, perhaps circulatory, and mildly mechanical. McPartland20 described iatrogenesis with this technique, but Upledger19 rightly noted that his case descriptions indicated improper technique involving too much force. Over all, the technique seems safe if applied correctly.

Fig. 1.

Inhibitive distraction

Within the context of this study, the relevant suggested effects of ID on the cervical spine involve inhibition of local and general posterior muscle tone, inactivation of suboccipital muscle MTrPs, and gentle joint mobilization. These effects are all hypothesized to result in an increase in cervical flexion AROM. Therefore, the purpose of this pilot study was to examine the immediate effects of ID on AROM into cervical flexion in patients with neck pain with or without concomitant headache. The main objective was to show whether, when used alone in a single treatment session, this intervention would significantly increase cervical flexion AROM. A secondary objective of this study was to see whether patient subgroups could be identified that might benefit more from ID by studying variables such as age, pain intensity, presence of headache, or pre-intervention AROM and by looking at patients' ability to identify pre- to post-intervention changes in their ability to actively move through a range of motion.

Methods and Materials

Subject Selection and Group Assignment

Recruitment of subjects and data collection took place over a 3-month period. The sample used in this study was a sample of convenience; 40 consecutive patients referred to Sjúkrapjálfun Reykjavíkur, a private PT practice in Reykjavík, Iceland, for discomfort in the cervical region were recruited into this study.

Our one inclusion criterion was a patient report of pain in the cervical region. This broad inclusion criterion was chosen on the assumption that any pain in the region and/or disorders resulting in pain would cause muscle dysfunction as discussed above leading to limitations of AROM cervical flexion that have been suggested to be amenable to management with ID. Exclusion criteria included a history of neck surgery, obesity to the extent that soft tissue approximation might limit cervical flexion, trauma to the head and neck area in the ten days prior to the study treatment, and diagnoses indicating neurological dysfunction, rheumatoid arthritis, or severe spondylarthrosis. Thus, the study sample was hypothesized to more likely have muscle dysfunction causing limitation of cervical AROM rather than restrictions based on progressive arthritic changes or sensory (proprioceptive or reflexive) changes due to disease. This was in line with the proposed effects of ID being mainly neurophysiological and secondarily mechanical as noted above.

The clinic's receptionist supervised a list of 40 consecutive numbers, to which an intervention or placebo treatment had been randomly assigned, and informed the therapist providing the intervention whether the experimental or the placebo technique was to be administered on the day of treatment. All subjects signed an informed consent form. The National Bioethics Committee of Iceland and the Data Protection Authority of Iceland approved this study.

Tests and Measures

Intensity of neck pain and cervical AROM are outcome measures that have been used previously to measure effectiveness of treatment for neck pain in clinical trials involving relaxation, acupressure and acupuncture, and medication22–24. In this study, we used an 11-point numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) to record pain intensity. The NPRS is commonly used to measure pain intensity with 0 indicating no pain and 10 the worst pain imaginable. The reliability and validity of NPRS have been well documented and are sufficient for clinical use; positive and significant correlations with other measures of pain intensity have been demonstrated as well as sensitivity to change due to treatments that are expected to have an impact on pain intensity25.

The CROM goniometer (Performance Attainment Associates, St. Paul, MN) was used to measure cervical sagittal plane flexion AROM. This test has been found to both be valid26 and reliable26–33. Both intra- and interrater reliability (ICC=0.95 and ICC=0.86, respectively) have been established as acceptable for clinical AROM measurements of neck flexion in a patient population32. A review of reliability studies for cervical ROM measurement tools concluded that the CROM was the most reliable instrument reviewed34. In this study, a magnifying glass was used to more clearly identify the numbers on the inclinometer. The starting position for pre- and post-intervention measurement was standardized on both occasions by measuring and keeping constant the distance from the occiput to a vertical pole with a measuring tape.

Intervention

For both the experimental and the placebo intervention, the patient was asked to rest supine on the treatment table. The experimental ID intervention had the therapist place the fingertips onto the suboccipital musculotendinous structures just caudal to the superior nuchal line and induce a sustained force in a ventrocranial direction, thus exerting compressive forces as well as a distraction to the cervical and suboccipital structures (Figure 1). The pressure applied to achieve muscle inhibition during treatment was applied slowly, maintained, and then released slowly; it was applied perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the muscles and tendons involved. The amount of applied pressure was adjusted to just less than that which would excite the muscle further, and as the therapist maintained the pressure and the patient's muscles relaxed, ideally the pressure was applied at an increasingly deeper level. Good palpatory awareness is important for correct execution of ID, as excessive pressure will have the opposite effect by causing irritation and an undesired increase in muscle tone. In other words, the amount of pressure applied was individualized according to therapist perception of the patient's tolerance as reflected by muscle response. This muscle response was constantly monitored and thus, the amount of pressure could change during the administration of this intervention. Thus, the force applied varied anywhere from light pressure and no distraction forces applied with the weight of the subject's head partially supported by the therapist's thenar eminences, to the full weight of the subject's head resting on the therapist's fingertips and distraction applied. The ID intervention was applied for 3 to 3.5 minutes.

Those in the control group rested their heads in the palms of the clinician for the same duration to mimic the treatment position as much as possible. In this way, these subjects received the effects of touch, warmth, and rest, without the actual proposed mechanical effects of the experimental ID intervention.

Therapists

Therapist A, a physical therapist with 20 years of experience and familiar with the CROM device, performed the measurements. A 2-week period prior to the start of data collections was used as a practice period for this therapist to obtain increased proficiency in the use of the CROM device. Therapist B, a physical therapist with 10 years of clinical experience and 6 years of experience with the technique under investigation, administered all interventions.

Procedure

All measurements and treatments were performed between 11 am and 3 pm in the same private examination room of the clinic in order to control for diurnal and environmental variations. After signing the informed consent form and prior to testing and treatment, we collected data on patient age, average day-to-day pain intensity rated on the NPRS, duration of symptoms, and whether headaches were a frequent part of their symptom presentation. Subjects were also asked about pain intensity rated on the NPRS at the time of each AROM measurement and pre- and post-intervention. Finally, subjects were asked whether they felt a subjective increase in their ability to perform the movement after the intervention.

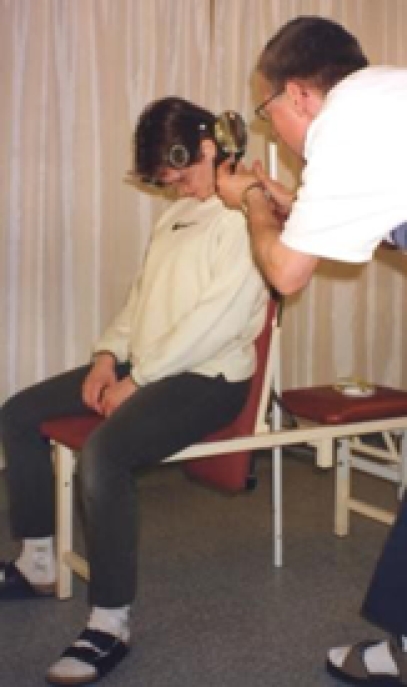

Therapist A performed all measurements. Subjects were seated in an upright chair for the measurements, with their feet on the ground and hands resting in the lap. They did not perform any type of warm-up exercise prior to AROM testing. Upper thoracic contact was maintained with the back of the chair, thus minimizing upper thoracic spine motion. The starting position was standardized from pre- to post-intervention measurement as noted above. The CROM device was affixed to the head of the patient, and the first reading was taken with the patient in the neutral position (Figure 2a). The patient was then asked to actively perform flexion of the cervical spine, according to standardized instructions, and a second reading was taken in the end-range position (Figure 2b). Flexion ROM was recorded as initial measurement subtracted from final measurement, e.g., 53° (final) − 0° (initial) = 53° of flexion.

Fig. 2a.

Starting position

Fig. 2b.

End position

After finishing the measurements, Therapist A left the room, and Therapist B entered. This therapist had been informed of the randomized intervention to be administered on the day of treatment. Therapist A was blinded to the intervention administered, and Therapist B was not made aware of any AROM or NPRS results until after the data collection had been completed. The patients were aware that the effects of a particular treatment were being investigated, but they were not given specific information with regard to the nature of the treatment. Thus, subjects were not informed whether they were in the experimental or control group prior to or during the session. Having administered the randomized intervention, Therapist B left the room. The subject rested in the supine position until Therapist A promptly re-entered. The patient then assumed the same starting position as for the first measurement, and a second measurement was taken in the same manner as before, approximately one minute after the intervention was completed. No other treatment intervention was offered to either group.

Statistical Analysis

Means, standard deviations (SD), and confidence intervals (CI) for AROM and NPRS scores were calculated for both groups. An unpaired t-test was used to compare the pre-intervention means of these characteristics between the two groups in order to evaluate for pre-intervention equivalence. We used chi-square tests to similarly evaluate for pre-intervention group equivalence with regard to subgroup categories.

The between-group difference for pre- to post-intervention changes in mean cervical flexion AROM was analyzed with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures.

Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients and linear regression analysis were used to examine the relationship between age and AROM and the relationship between pre-intervention AROM and the degree of AROM changes seen from pre- to post-intervention measurements. We also used an unpaired t-test to compare the mean pre- to post-intervention change in AROM between those who stated they felt an improved ability to perform the movement and those who stated they did not.

Because the data showed a certain trend towards a greater improvement in AROM with increased subject age, we divided the subjects into three age groups, grossly by decades (16–30, 31–40, and 41–48) and in accordance with the methodology used in previous studies27,33. These age groups were used as a factor in the ANOVA analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze the mean pain ratings between the three age groups.

The Microsoft Excel 2000 program was used for the t-tests, while others were calculated by using SAS (Statistical Analysis System) statistical software (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC). For the repeated measure ANOVA, the SAS mixed procedure was used. The level of significance (α) was set at 5%. Thus, results were considered significant at P=0.05 or less.

Results

Subjects

Subjects consisted of 31 women and 9 men (mean age 34.7 years; range 16–48 years). Over all, 27 subjects reported pain in the cervical region > 6 months and 23 complained of a regular occurrence of headaches. The patients' overall mean NPRS score for their average day-to-day pain was 5 (range 2–9).

The statistical tests showed that the experimental and control group at pre-intervention were not significantly different with regard to subject characteristics such as age, gender, pain intensity, duration of pain, and whether they had complaints of headaches. Mean pre-intervention AROM (±SD) was 48.6° (±10.9°) and 50.9° (±13°) for the experimental and control groups, respectively (P=0.534, Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mean AROM and mean change in AROM

| Controls (n=20) | 95% CI | Experim (n=20) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | 50.9° (13°) | 44.9-57 | 48.6° (10.9°) | 43.5-53.6 |

| Post-intervention | 52.1° (11.4°) | 46.8-57.4 | 50.9° (9.2°) | 46.6-55.2 |

| Mean change | 1.2° (5.8°) | −1.5-3.9 | 2.4° (6.2°) | −0.5-5.3 |

Intervention and Changes in Active Range of Motion

Average pre- to post-intervention cervical flexion AROM increases were 2.4° for the experimental group and 1.2° for the control group (Table 1). There were no significant between-group differences with regard to these pre- to post-intervention changes in AROM (P=0.767, Table 2). In contrast, the within-group AROM increase from pre- and post-intervention for both groups combined did achieve statistical significance (P=0.046, Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary table for the repeated measures ANOVA.

| Source of variance | Num DF | Den DF | F value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between subjects | ||||

| Intervention | 1 | 34 | 0.21 | 0.653 |

| Three age groups | 2 | 34 | 2.47 | 0.100 |

| Within subjects | ||||

| Prepost AROM | 1 | 34 | 4.28 | 0.046 |

| Prepost*interv. | 1 | 34 | 0.09 | 0.767 |

| Prepost*age grp. | 2 | 34 | 1.90 | 0.165 |

| Prepost*age*interv. | 2 | 34 | 0.22 | 0.924 |

The sources of variance between subjects are the intervention and age group variables. The source of variance within subjects looks at the change in AROM between measurements (pre- and post-intervention), regardless of the type of intervention; then with regard to intervention; thirdly the change in AROM between age groups regardless of intervention; and lastly the interaction between these variables including the intervention.

Age and Active Range of Motion

A statistically significant, negative correlation was found between subject age and pre-intervention AROM (r=−0.36; P=0.025): older subjects tended to have less pre-intervention AROM. However, when using age and intervention (experimental or placebo) as additional factors in the ANOVA, the pre- to post-intervention AROM changes were not statistically significant (P=0.924, Table 2). In both groups combined, subjects in the different age groups also did not show significantly different changes in pre- to post-intervention AROM (P=0.165, Table 2).

Age and Pain

A statistically significant, negative correlation was found between age and NPRS scores for average day-to-day pain intensity (r=–0.39; P=0.015); older subjects tended to report lower NPRS scores. The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant difference between subgroup scores for average day-to-day pain of the three age groups for all subjects (P=0.048, Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Post-intervention changes in AROM with respect to age for the two groups.

| Control group | Experimental group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | Range of change | Mean change | n | Range of change | Mean change | n | All subj. avg.pain |

| 16–30 (24.7) | –10° to +3° | –1.5° (5.4°) | 6 | –6° to +5° | +1.2° (3.9°) | 6 | 5.7 (1.6) |

| 31-40 (35.8) | –6° to +9° | +0.95° (4.9°) | 10 | –8.5° to +16° | +2.1° (8.7°) | 7 | 5.5 (1.3) |

| 41-48 (43.9) | 0° to +16° | +5.25° (7.0°) | 4 | –3° to +13° | +3.7° (5.2°) | 7 | 4.0 (1.7) |

Mean change shows one SD in parentheses

Other Subgroups and Changes in Active Range of Motion

Those patients experiencing lower levels of pain, those suffering from headaches, and those who had had discomfort for six months or more increased their AROM slightly more than the others when receiving the ID treatment (Tables 4–6). This difference did not, however, exceed the cut-off set for statistical significance in this study.

TABLE 4.

Mean post-intervention changes in AROM with respect to pre-intervention pain level.

| Control group | n | Experimental | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low level pain | 0.4° (3.6°) | 9 | 3.8° (7.1°) | 9 |

| Higher level pain | 1.8° (7.3°) | 11 | 1.2° (5.3°) | 11 |

Low level pain = 0-3; higher level pain = 4-10; SD in parentheses

TABLE 6.

Mean post-intervention changes in AROM with respect to complaints of headaches.

| Control group | n | Experimental | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c/o headaches | 1.8° (6.8°) | 10 | 3.7° (6.3°) | 13 |

| no headaches | 0.6° (4.9°) | 10 | –0.1° (5.4°) | 7 |

SD in parentheses

Statistically significant, negative correlations were found between the degree of pre-intervention AROM and post-intervention changes for both the control (r=−0.48; P=0.031) and experimental groups (r=−0.54; P=0.015), indicating that those with less pre-intervention motion showed on average a larger change in AROM, regardless of which group they were in.

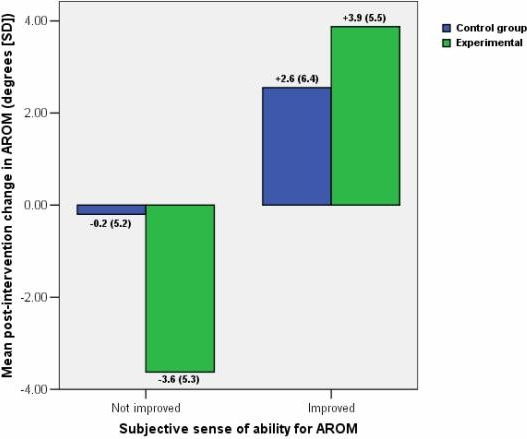

Subject Awareness of Changes in Active Range of Motion

Half of the subjects in the control group reported a subjectively improved ability to perform post-intervention cervical flexion AROM while half reported no improvement. However, the mean changes in their AROM were not significantly different (P=0.302, Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Sense of improved AROM.

In the experimental group, 16 subjects reported sensing an improved ability to perform the post-intervention movement whereas 4 reported no improvement. There did exist a significant difference in the mean changes in pre- to post-intervention AROM between these two subgroups in the experimental group (P=0.025, Figure 3)

Over all, in the experimental and placebo group combined, a mean increase in AROM was demonstrated by patients reporting improved post-intervention AROM (+3.4 ± 5.8°), which was significantly different from the mean decrease in AROM demonstrated by those reporting no improvements (−1.2±5.3°; P=0.019).

Discussion

The main goal of this pilot study was to show whether, when used in isolation, ID would lead to a significant and immediate increase in cervical flexion AROM in patients with neck pain with or without concomitant headache. The results did not show a statistically significant advantage of ID over the placebo treatment of rest, touch, and warmth. The subject group as a whole showed a significant increase in active flexion, but the clinical significance of this increase can be questioned, as the mean increase of both groups combined was less than 2°. Neither group demonstrated a post-intervention increase in mean AROM beyond the upper limits of the 95% confidence interval for the mean pre-intervention AROM. This underscores how small the mean change in AROM was with respect to the large variability of AROM measurements. The secondary goal of the study was to identify subgroups of patients who might benefit from ID. For this, we looked specifically at factors such as age, intensity and duration of symptoms, pre-intervention AROM, and headaches as a prominent part of the subjects' symptoms. No statistically significant differences were found in between-group changes in their mean pre- to post-intervention AROM measurements for the various studied subgroups.

Threats to internal validity that could have affected our results were considered. A learning effect is possible, the subjects being more familiar with performing the requested cervical flexion movement the second time around. However, Christensen and Nilsson35 noted no testing effect for cervical flexion during six goniometric measurements over a 3-week period. Recommendations with regard to instrumentation, standardizing measurement procedures, and the experimental setting34,36 were followed to a great extent. A confounding factor may have been introduced by allowing patients to move in any manner they chose from the treatment table and into the chair for the second measurement. Any biological variations and/or human errors, however, would be expected to occur equally in the experimental and control groups as the result of random group assignment.

Although equally affecting both groups, an important issue that needs to be addressed concerns the observed variability of change in AROM. In this study, the amount of change in active cervical flexion over all varied greatly, regardless of whether the patient received the pressure treatment or the placebo treatment, and ranged from a decrease of 10° to an increase of 16°. A large variability in cervical AROM has been reported for both asymptomatic and symptomatic subjects, measured with an electro-goniometer and an electromagnetic tracking system35,37. Alteration in proprioceptive sensibility is a dysfunction recognized in patients with cervical pain9,38, and Rheault et al31 suggested that a “guarding” effect at the end of AROM may be a characteristic of patients with neck dysfunction. Both proprioceptive dysfunction and end-range guarding may have led to the great degree of variability between measurements observed in the symptomatic subjects participating in this study, in spite of our efforts to minimize measurement errors. It is possible that the observed variability “washed out” the small pre- to post-intervention changes observed in this study, and we have to consider that AROM measurements may not be an appropriate outcome measure to study the effects of ID and other manual interventions. Alternatively, variability could possibly be decreased by selection criteria that result in a more homogenous patient population.

As noted above, we were not able to identify subgroups more likely to benefit from ID; however, a trend for the greatest post-intervention changes was found in those subjects in the experimental group, who complained of headaches, indicated lower levels of pain, had less pre-intervention AROM, and had suffered discomfort for > 6 months (Table 4). These subjects may have had symptoms that were more likely to respond to a muscle inhibitory treatment or they may have tolerated the treatment better due to a more chronic state and lower levels of pain, or both. In this study, a number of the patients in the experimental group did not tolerate the full application of ID and received only gentle pressure not dissimilar from the placebo intervention. Consequently, a sufficient mechanical and/or neurophysiological effect was probably not obtained and statistical significance of between-group differences was likely affected. Future studies and possibly clinical application of this technique should likely limit selection criteria to reflect the trend for greater improvement in chronic patients with headaches, lower pain levels, and less AROM.

A further possible selection criterion might be the type of headache. We discussed above the role of MTrPs in tension-type headaches14–16 and also noted that techniques similar to ID have been suggested for the management of these trigger points12. Although systematic reviews39,40 have shown strong evidence for the effectiveness of manipulative interventions for cervicogenic headaches, they have not done so for tension-type headaches. However, for the latter type of headache, the use of soft-tissue techniques has been supported40. This would seem to indicate that perhaps our selection criteria for clinically using and studying ID should also reflect a potential greater benefit in patients with tension-type as compared to cervicogenic headaches.

Age and gender are other potential predictive variables for a response to ID. The oldest individual in the present study was only 48 years old, and gender would not be expected to influence cervical flexion AROM for this study population27,29,30,33,36,41–43. Increasing age has been shown to cause a progressive decrease in cervical AROM8,10,27,30,32,36,41–44. This is supported by the present study in which we found a statistically significant negative correlation between age and pre-intervention cervical flexion AROM. However, age does not account for a large portion of the variation in cervical flexion in this relatively young subject group (r2=0.13). Over all, the pre-intervention AROM for our patient group was a little under 50°, which is 10° below the average normative values reported for cervical flexion (measured with single inclinometers) in this age group36. Due to the age distribution of our subjects, this study does not allow for any inference with regard to the effect of age and gender on the potential effectiveness of ID.

The mean pre- to post-intervention change, even for both groups combined, was very small. One way to interpret this change is to look at the minimal detectable change (MDC95). If a change exceeds the MDC95, we can be confident with a 95% certainty that a true change has in fact occurred. We can calculate this MDC95 by using the formula MDC95 = (1.96) × (√2) × standard error of measurement (SEM)45. The purpose of this study was not to establish intrarater reliability of our cervical AROM measurement and, therefore, the SEM was calculated using an ICC reported in the literature. Youdas et al32 established an intrarater ICC=0.95 for cervical flexion using the CROM device in a patient population. The overall standard deviation (SD) for the mean of our pre-intervention cervical flexion measurement for both groups combined was 11.9°. We can now estimate the SEM of 2.6° with the formula: SEM = SD × √(1−ICC)46,47. This provides us in turn with an MDC95 of 7.2°, which would indicate that the pre- to post-intervention change seen in the present study was not a “true” increase in cervical flexion. The large SD of 11.9° indicates the need for stricter selection criteria that would result in a more homogenous study or—for clinical purposes—patient population. Given a more homogenous population, the SD and SEM would be smaller, as would the MDC95, and a possible significant effect would be more easily detected.

Information was limited on the magnitude of change in cervical flexion AROM that we might expect as a result of the intervention used in the present study. This investigation is described as a pilot study, in part, due to our limited ability to do a power analysis before the study. The large variability of cervical AROM measurements within both groups and the small effect size is reflected in low statistical power. Using a one-tailed test based on the assumption that the experimental intervention was more effective than the placebo intervention, we calculated a power of 1–β=15.6%. This creates a high probability of a Type II error and limits our ability to detect statistically significant pre- to post-intervention differences between groups. The results showed 1.2° difference in the change of AROM between the control and treatment groups, and the SD of the changes was around 6° (Table 1). In the experimental subgroups, where the greatest increase in range of movement was seen, the increase was 2.0–3.4° greater than for the respective control groups (Table 4). Power analysis shows that if the expected effect of the experimental treatment over the placebo treatment were 2° with an SD of 6°, 111 individuals are needed in each group in order for the statistical power (1−β) to be 80%. If the MDC95 of 7.2° calculated above were used as a required between-group difference, of course an even larger sample size would be indicated. Stricter inclusion criteria, as discussed earlier, could lead to fewer subjects needed per group by diminishing the variability of AROM measurements. Moreover, lower variability would help identify with a greater degree of confidence absence or presence of statistically significant differences between groups

The MDC95 represents one aspect of responsiveness; the other aspect is the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). Generally, the MCID is larger than the MDC95. However, in this study, the patients who reported sensing an improved range of flexion increased their AROM significantly (by 3.4° on average), compared to those who reported no post-intervention improvement (a mean decrease of 1.2°) (Figure 3). This underscores the difficulties discussed above surrounding the MDC95 and suggests that the MCID may in fact be much smaller, i.e., that a small degree of change may matter, functionally, for the patient.

The results of the present study suggest that applying sustained pressure to the sub-occipital region does not result in improved cervical flexion AROM. The results do not, however, exclude the occurrence of potential short-lived neurophysiological inhibitory effects, as these were not directly measured. Studies on the effects of tendon pressure on muscle activity have found that although excitability of the motor neurons supplying the muscles decreased, this effect lasted only as long as the stimulus was present48–50. If immediate short-lived inhibitory effects are, in fact, achieved, sustained pressure treatment may be suitable as a preparatory treatment for soft-tissue or joint manipulation, which should take place immediately after the application of the inhibitory pressure. This may have implications for future study with ID as part of a pragmatic physical therapy intervention and for its use in clinical practice. Our results, however, show no indication that any effects due to the sustained pressure alone are maintained long enough to be beneficial to the patient, e.g., for self-stretching or ROM exercises after the pressure is released.

The placebo intervention may have been a confounding factor in that relaxation and touch may have had a positive effect on some subjects in the control group. The area of touch was large, which can result in raised temperature in the most superficial soft tissues. Superficial heat increases the extensibility of collagen tissue, reduces muscle spasm, produces analgesia and hyperemia, and increases metabolism51,52. However, in the absence of a deforming force, heat will not alter collagen deformation during subsequent movement52–54, and in any case the physiological effects would have been small and limited to the most superficial tissues.

A final consideration is that the ID technique may have a local rather than the proposed regional effect, i.e., that its effect is limited to the suboccipital muscles. If this is the case, the expected changes in AROM may be limited to cranio-cervical motion and might not be captured with a general cervical flexion AROM measurement.

Conclusion

This pilot study researched the immediate effects of ID on cervical flexion AROM in patients with neck pain with or without associated headache. It also attempted to identify potential subgroups more amenable to this technique based on subject age, pain intensity, presence of headache, or pre-intervention AROM. The results did not show a statistically significant advantage of ID over the placebo treatment. We were also unable to identify potential subgroups more likely to respond to ID, although a trend emerged for greater improvement in chronic patients with headaches, lower pain levels, and less AROM.

A large variability in AROM and intervention response contributed to the low power observed in the present study. Future studies should use selection criteria that are likely to produce a more homogenous study population by including only patients with symptoms of greater than 6 months' duration, headaches, lower pain levels, and more restricted pre-intervention AROM. To allow for inferences with regard to the predictive validity of subject age with regard to outcome, older subjects will need to be recruited. Future studies may compare the effects of ID on patients with cervicogenic versus tension-type headache, or as part of a pragmatic program to be directly followed by other manual interventions. If AROM measurements are selected as outcome measures, perhaps cranio-cervical rather than general cervical flexion measurements should be considered.

The limitations in this pilot study do not allow us to make inferences either way; ID may or may not have an immediate effect on cervical flexion AROM. The trend for greater effect noted in chronic patients with headaches, lower pain levels, and less AROM, in our opinion, warrant further study into this technique and continued—albeit more discerning—use of this technique in clinical practice.

TABLE 5.

Mean post-intervention changes in AROM with respect to months of pain.

| Control group | n | Experimental | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >6 months pain | 0.4° (4.5°) | 13 | 3.3° (6.6°) | 14 |

| <6 months pain | 2.6° (8.0°) | 7 | 0.25° (4.6°) | 6 |

SD in parentheses

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the primary author's Master of Health Science degree at the Institute of Physical Therapy, University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, Division of Advanced Studies in St. Augustine, FL. The authors thank Porgeir Óskarsson and Pórarinn Sveinsson for their contribution during data collections and data analysis, respectively. The work was supported by a grant from the research fund of the Association of Icelandic Physiotherapists in Iceland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Douglass AB, Bope ET. Evaluation and treatment of posterior neck pain in family practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:S13–S22. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.suppl_1.s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guez M, Hildingsson C, Stegmayr B, Toolanen G. Chronic neck pain of traumatic and non-traumatic origin. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:576–579. doi: 10.1080/00016470310017983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Issa TS, Huijbregts PA. Physical therapy diagnosis and management of a patient with chronic daily headache: A case report. J Manual Manipulative Ther. 2006;14:E88–E123. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Headache Fact Sheet. Lifting the Burden Available at: http://www.l-t-b.org/pages/18/index.htm Accessed January 9, 2007.

- 5.Haldeman S, Dagenais S. Cervicogenic headaches: A critical review. Spine J. 2001;1:31–46. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(01)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boissonnault WG. Prevalence of comorbid conditions, surgeries, and medication use in a physical therapy outpatient population: A multi-centered study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:506–519. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1999.29.9.506. discussion 520-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alaranta H, Hurri H, Heliövaara M, Soukka A, Harju R. Flexibility of the spine: Normative values of goniometric and tape measurements. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1994;26:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rix GD, Bagust J. Cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility in patients with chronic, nontraumatic cervical spine pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:911–919. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dvorák J, Panjabi MM, Grob D, Novotny JE, Antinnes JA. Clinical validation of functional flexion/extension radiographs of the cervical spine. Spine. 1993;18:120–127. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199301000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantu RI, Grodin AJ. Myofascial Manipulation: Theory and Clinical Application. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS. Travell and Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Volume 1: Upper Half of Body. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas KR, Polus BI, Rich PS. Latent myofascial trigger points: Their effect on muscle activation and movement efficiency. J Bodywork Movement Ther. 2004;8:160–166. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Gerwin RD, Pareja JA. Trigger points in the suboccipital muscles and forward head posture in tension-type headache. Headache. 2006;46:454–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Pareja JA. Myofascial trigger points in the suboccipital muscles in episodic tension-type headache. Man Ther. 2006;11:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Cuadrado ML, Pareja JA. Myofascial trigger points, neck mobility, and forward head posture in unilateral migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1061–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Pareja JA. Forward head posture and neck mobility in chronic tension-type headache: A blinded, controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:314–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paris SV. Course Notes: Introduction to Spinal Evaluation and Manipulation. 2nd ed. St. Augustine, FL: Patris Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Upledger JE. Response to: Craniosacral iatrogenesis. J Bodywork Movement Ther. 1996;1:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPartland JM. Craniosacral iatrogenesis. J Bodywork Movement Ther. 1996;1:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaitow L, Walker-Delany J. Clinical Applications of Neuromuscular Techniques. Vol 1: The Upper Body. Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip YB, Tse SH. An experimental study on the effectiveness of acupressure with aromatic lavender essential oil for sub-acute, non-specific neck pain in Hong Kong. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2006;12:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giles LGF, Muller R. Chronic spinal pain: A randomized clinical trial comparing medication, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation. Spine. 2003;28:1490–1503. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200307150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viljanen M, Malmivaara A, Uitti J, Rinne M, Palmroos P, Laippala P. Effectiveness of dynamic muscle training, relaxation training, or ordinary activity for chronic neck pain: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;327:475. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7413.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen MP, Karoly P. I. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tousignant M, de Bellefeuille L, O'Donoughue S, Grahovac S. Criterion validity of the cervical range of motion (CROM) goniometer for cervical flexion and extension. Spine. 2000;25:324–330. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hole DE, Cook JM, Bolton JE. Reliability and concurrent validity of two instruments for measuring cervical range of motion: Effects of age and gender. Man Ther. 1995;1:36–42. doi: 10.1054/math.1995.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capuano-Pucci D, Rheault W, Aukai J, Bracke M, Day R, Pastrick M. Intratester and intertester reliability of the cervical range of motion device. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ordway NR, Seymour R, Donelson RG, Hojnowski L, Lee E, Edwards WT. Cervical sagittal ROM analysis using 3 methods. Spine. 1997;22:501–508. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199703010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peolsson A, Hedlund R, Ertzgaard S, Öberg B. Intra- and inter-tester reliability and range of motion of the neck. Physiother Can. 2000;3:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rheault W, Albright B, Byers C, et al. Intertester reliability of the CROM device. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1992;15:147–150. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1992.15.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youdas JW, Carey JR, Garrett TR. Reliability of measurements of cervical spine range of motion: Comparison of three methods. Phys Ther. 1991;71:98–106. doi: 10.1093/ptj/71.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Youdas JW, Garrett TR, Suman VJ, Bogard CL, Hallman HO, Carey JR. Normal range of motion of the cervical spine: An initial goniometric study. Phys Ther. 1992;72:770–80. doi: 10.1093/ptj/72.11.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jordan K. Assessment of published reliability studies for cervical spine range-of-motion measurement tools. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23:180–195. doi: 10.1016/s0161-4754(00)90248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christensen HW, Nilsson N. Natural variation of cervical range of motion: A one-way repeated-measures design. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21:383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen J, Solinger AB, Poncet JF, Lantz CA. Meta-analysis of normative cervical motion. Spine. 1999;24:1571–1578. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergman GJD, Knoester B, Assink N, Dijkstra PU, Winters JC. Variation in the cervical range of motion over time measured by the “Flock of Birds” electromagnetic tracking system. Spine. 2005;30:650–654. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155414.03723.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Revel M, Andre-Deshays C, Minguet M. Cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility in patients with cervical pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Pareja JA. Spinal manipulative therapy in the management of cervicogenic headache. Headache. 2005;45:1260–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.00253_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Miangolarra JC, Barriga FJ, Pareja JA. Are manual therapies effective in reducing pain from tension-type headache? A systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:278–285. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000173017.64741.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castro WHM, Sautmann A, Schilgen M, Sautmann M. Non-invasive three-dimensional analysis of cervical spine motion in normal subjects in relation to age and sex: An experimental examination. Spine. 2000;25:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lind B, Sihlbom H, Nordwall A, Malchau H. Normal range of motion of the cervical spine. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70:692–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayer T, Brady S, Bovasso E, Pope P, Gatchel RJ. Non-invasive measurement of cervical tri-planar motion in normal subjects. Spine. 1993;18:2191–2195. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dvorák J, Antinnes JA, Panjabi M, Loustalot D, Bonomo M. Age and gender-related normal motion of the cervical spine. Spine. 1992;17:S393–S398. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199210001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stratford P. Getting more from the literature: Estimating the standard error of measurement from reliability studies. Physiother Can. 2004;56:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Statistical measures of reliability. In: Portney LG, Watkins MP, editors. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1993. pp. 505–528. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231–240. doi: 10.1519/15184.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kukulka CG, Beckman SM, Holte JB, Hoppenworth PK. Effects of intermittent tendon pressure on alpha motoneuron excitability. Phys Ther. 1986;66:1091–1094. doi: 10.1093/ptj/66.7.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kukulka CG, Fellows WA, Oehlertz JE, Vanderwilt SG. Effects of tendon pressure on alpha motoneuron excitability. Phys Ther. 1985;65:595–600. doi: 10.1093/ptj/65.5.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leone JA, Kukulka CG. Effects of tendon pressure on alpha motoneuron excitability in patients with stroke. Phys Ther. 1988;68:475–480. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaul MP. Superficial heat and cold: How to maximize the benefits. Phys Sports Med. 1994;22(12):65–74. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1994.11947720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michlovitz SL. Biophysical principles of heating and superficial heating agents. In: Michlovitz SL, Wolf SL, editors. Thermal Agents in Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Co; 1987. pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitney SL. Physical agents: Heat and cold modalities. In: Scully RM, Barnes MR, editors. Physical Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1989. pp. 844–875. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zachazewski JE. Improving flexibility. In: Scully RM, Barnes MR, editors. Physical Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1989. pp. 698–738. [Google Scholar]