Abstract

Physical medicine, which in the context of this article includes mechanotherapy, hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, electrotherapy, light therapy, air therapy, and thermotherapy, became a new field of labor in the healthcare domain in the Netherlands around 1900. This article gives an account of the introduction and development of mechanotherapy as a professional activity in the Netherlands in the 19th century. Mechanotherapy, which historically included exercises, manipulations, and massage, was introduced in this country around 1840 and became one of the core elements of physical medicine towards the end of that century. In contrast to what one might expect, mostly physical education teachers, referred to as “heilgymnasts,” dedicated themselves to this kind of treatment, whereas only a few physicians were active in this field until the 1880s. When, in the last quarter of the 19th century, differentiation and specialization within the medical profession took place, physicians specializing in physical medicine and orthopaedics began to claim the field of mechanotherapy exclusively for themselves. This led to tensions between them and the group of heilgymnasts that had already been active in this field for decades. The focus of attention in this article is on interprofessional relationships, on the roles played by the different professional organizations in the fields of physical education and medicine, the local and national governments, and the judicial system, and on the social, political, and cultural circumstances under which developments in the field of mechanotherapy took place. The article concludes with the hypothesis that the intra- and inter-occupational rivalries discussed have had a negative impact on the academic development of physical medicine, orthopaedics, and heilgymnastics/physical therapy in the Netherlands in the first half of the 20th century.

Key Words: The Netherlands, Nineteenth Century, Physical Medicine, Orthopaedics, Physical Therapy, Physical Education, Mechanotherapy, Professionalization

Physical medicine or physical therapy has very ancient origins. For thousands of years, people with illnesses and disabilities were treated with various methods, making use of movements (with or without the aid of mechanical devices) as well as air, water, heat and cold, electricity, and light1, 2. Despite its long history, however, astonishingly little historical research has been done on this special branch of medicine. A quick glance through the pertinent literature in the field of the history of medicine of the last two decades reveals that the development of physical medicine as a professional activity in the field of healthcare in the past two centuries has seldom been an object of scholarly conducted research. Before this period the situation wasn't much better. In 1985, Glenn Gritzer and Arnold Arluke pointed out that this field of interest has been ignored by sociologists and historians alike3. Prompted by their comment, a historical research program was implemented in the Netherlands aiming to get a better insight into the development of physical medicine in that country in the past two centuries. Since the results thereof are predominantly published in Dutch4 – 10, this article hopes to inform a broader circle of physical therapists, medical historians, and other interested readers.

During the second half of the 19th century, a period of increasing specialization in the field of medicine, terms like “physical medicine,” “physical therapy,” “physiotherapy,” and the like came into use to categorize the various healing methods of exercise, manipulation, and massage (also collectively known as mechanotherapy), hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, electrotherapy, light therapy, air therapy, and heat and cold therapy (thermotherapy) under one heading. In 1851, the military physician Lorenz Gleich (1798–1865) had already used the term “physiotherapie” (German for physical therapy) in one of his publications11. One of the first to use the generic term “physikalische Heilmethoden” (German for physical therapies) was the German physician and professor of medicine at Würzburg University, M.J. Rossbach (1842–1894)12. In the Netherlands, there was a growth in publications on physical medicine around 1900; specialized journals concerning aspects of physical medicine were launched and the first organizations of physicians dedicated to aspects of physical medicine were founded. Although the various healing methods of mechanotherapy (exercises, manipulations, and massage), hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, electrotherapy, light therapy, air therapy, and heat and cold therapy (thermotherapy) had been grouped together by 1900, it is important to note that each of these therapies had its own interesting development that is eligible for further historical research, as Günter B. Risse has already pointed out13.

This article provides an account of the introduction and further development of mechanotherapy as a professional activity in the Netherlands in the 19th century. It is based mainly on primary sources (e.g., journals in medicine and physical education from the 19th century). In the few relevant archives, little could be found on the constituents of physical medicine. Secondary sources (well researched and annotated studies) that shed a light on this topic are almost entirely nonexistent. There are several reasons for focusing on the history of mechanotherapy in particular. The first one is practical. The history of all the constituents of physical medicine in the Netherlands in the 19th century is too expansive to cover easily since research in this field is still in its infancy. Secondly, doing research on the developments in mechanotherapy in the 19th century is not only important because mechanotherapy became one of the core elements of physical medicine in the Netherlands around 1900, but, even more importantly, these developments had a big impact on how physical medicine as a whole would evolve in the first half of the 20th century. Thirdly, studying the development of mechanotherapy is very interesting from a socio-historic point of view, since there were different groups of professionals active in this field, which allows us to look into interprofessional relationships in the healthcare domain and analyze the struggle between these professional groups over the preservation and expansion of their occupational boundaries and professional autonomy. This is why this article focuses on the roles played by individual and collective actors and on the social, political, and cultural circumstances under which developments in this field took place. The chosen perspective is based on a sociological model for professionalization and collective power developed by the Dutch sociologist T.P.W.M. van der Krogt. This eclectic model is based upon trait, function, and power/control approaches to professionalization14.

This article is divided in three chronological sections. In the first section, attention is paid to certain developments in the Netherlands and in several neighboring countries in the first half of the 19th century that prepared the ground for the introduction of medical gymnastics. Within the context of the ongoing discourse among Dutch intellectuals at the time concerning the importance of physical education in the upbringing of new generations, teachers and physicians gradually became more receptive to other views on how to use gymnastic exercises. They saw medical gymnastics (including massage), as developed in Sweden and Germany, as a very promising form of conservative medical treatment and began to use it—sometimes in combination with other therapies—to treat illnesses and disabilities for which there was no satisfactory solution at the time. The first signs of the actual use of mechanotherapy (exercises, manipulations, and massage) in the Netherlands were spotted in publications around 1840. At that time, it was referred to as “medical gymnastics” (or Swedish gymnastics, Nordic gymnastics, kinesitherapy, or orthopaedic gymnastics). The second section shows that there was an increasing interest in the application of medical gymnastics, by then referred to as “heilgymnastics” (in Dutch: heilgymnastiek) from the 1860s onwards. In contrast to what one perhaps might expect, mostly physical education teachers, soon referred to as “heilgymnasts” (in Dutch: heilgymnasten), dedicated themselves to this kind of treatment whereas only a few physicians were active in this field. We take a closer look at these practitioners, how and where they practiced, and what kind of patients they treated. When, during the late 1870s and 1880s, differentiation and specialization in the field of medicine intensified and new legislation in the healthcare domain came into effect, conflicts arose between heilgymnasts and members of the medical profession, especially those who were specializing in orthopaedics and physical medicine. These conflicts will be analyzed together with the roles played by the different professional organizations in physical education and medicine, the local and national governments, and the judicial system. Finally, the third section focuses on the founding of the Society for Practising Heilgymnastics in the Netherlands (in Dutch: Genootschap ter Beoefening van de Heilgymnastiek in Nederland) by heilgymnasts as early as 1889. The aims of this society, the first of its kind in the world, were to look after the interests of heilgymnasts, enable them to elevate their professional level, and bring about a better understanding with physicians. Despite what heilgymnasts had hoped for, however, the founding of the society did not bring about a détente between physicians and heilgymnasts. On the contrary, it lifted the controversy from the level of heated discussions between individuals in periodicals to that of a dispute between professional organizations, since around 1900 physicians had founded their own organizations in physical medicine and orthopaedics. The tensions between these groups of professionals would last until the second World War and are assumed to be, at least partly, responsible for the slow academic development of physical medicine, orthopaedics, and heilgymnastics/physical therapy in the Netherlands in the first half of the 20th century.

Introduction of Medical Gymnastics in the Netherlands: 1840–1860

The first signs of the use of medical gymnastics in the Netherlands appear in publications around 1840. Preceding these signs, several significant developments had taken place in neighboring countries as well as in the Netherlands.

Developments in Neighboring Countries: Germany and Sweden

In Germany, the work of the so-called “Philanthropen” around 1800 was very influential15. Of these, the German pedagogue J.C.F. GutsMuths (1759–1839) was the most significant. In his book Gymnastik für die Jugend (1793), he criticized the prevailing notions on education, which were, to his taste, too much concentrated on the intellect16. Influenced by thoughts on education of J. Locke (1632–1704) and J.J. Rousseau (1712–1778) and inspired by the “Leibeskultur” (German for: physical culture) of the ancient Greeks and Germans/Teutons, GutsMuths wanted to combine the physical perfection of the so-called primitive with the cognitive abilities of the civilized human, creating a harmony between body and mind. An extensive physical education program should play an important role in the education of youngsters. Certainly at a time when the Napoleonic wars were directing attention as never before towards the need for physical fitness among the masses, his thoughts easily found their way through Europe17. Other pedagogues and gymnasts who had an impact on developments in physical education in the Netherlands during the late 18th and the first half of the 19th century were F.L. Jahn (1778–1852), E.W.B. Eiselen (1792–1846), and somewhat later A. Spiesz (1810–1858). They were all industrious in this field and published several influential books that were read by Dutch intellectuals18 – 21.

The most important stimulant for the rise of medical gymnastics in the Netherlands, however, came from Sweden at the beginning of the 19th century. The work of the Swedish gymnast P.H. Ling (1776–1839) is considered crucial for the introduction and application of medical gymnastics in and outside Sweden in the first half of the 19th century (Figure 1). Influenced by GutsMuths, the Romantic natural philosopher F.W. Schelling (1775–1854) and Cong-Fou based on the teachings of the Tao-Sée22 – 25, Ling developed a physical education system comprising military, aesthetical, pedagogical, and medical gymnastics. His work was continued by his disciples C.A. Georgii (1808–1880), L.G. Branting (1799–1881), and C.F de Ron (1809–1887). In Ling's Central Gymnastic Institute (CGI) in Stockholm, founded in 1813, patients were treated, and training and guidance were given to those who wanted to become medical gymnasts. Many German physicians, such as M.M. Eulenburg (1811–1887), D.G.M. Schreber (1808–1861), K.H. Schildbach (1824–1888), and A.C. Neumann (1803–1870), and physical education teachers, such as H. Rothstein (1815–1865), H.O. Kluge (1818–1882), J.A.L. Werner (1794–1866), and A.S. Ulrich (1826–1889), visited this institute. All of them started institutes for medical gymnastics in Germany. The activities and publications of Ling, his disciples, and the German physicians and physical education teachers changed the viewpoint on physical education and drew attention to the use of exercises for medical ends in many countries, including the Netherlands.

Fig. 1.

Per Henrik Ling (1776–1839), stimulator of medical gymnastics (Source: Van Schagen KH, ed. De Lichamelijke Opvoeding in de Laatste Drie Eeuwen. Haar Ontwikkeling, Doel en Stelselmatige Toepassing. Deel I. [Dutch for: Physical Education in the last Three Centuries: Development, Goal, and Systematic Implementation. Part I]. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Nijgh & Van Ditmar, 1926.)

Education and Physical Education in the Netherlands

When Belgium was separated from the Netherlands and both became independent states in 1840, a constitutional revision was necessary. Some of the leading Liberals as well as progressive Roman Catholics in the Netherlands tried to introduce a number of democratic reforms. But, because of strong opposition by King William II (1792–1849), who reigned from 1840–1849, they had to wait for almost a decade until an agreement was reached in favour of these reforms. It was the threat of revolution in 1848—revolutions haunted many European states that year—that made the King accept rigorous changes in the constitution. One of the things that would be altered was the educational system.

The spread of Enlightenment ideas on education, mainly coming from Germany, had already been influencing the thinking about the educational system in the Netherlands in the years before 1848. As knowledge was considered to be the source of all virtues in society, intellectuals were convinced that it should be widely spread in order to prevent the masses from sliding off into pauperism. Furthermore, education for all was thought to be beneficial for the desired change from a predominantly agricultural society to an industrial one.

At the same time, however, it was emphasised in various Dutch publications on education that intellectual education was heavily overrated in the schools4, 26. The popular creed “mens sana in corpore sano” (Latin for: A healthy mind in a healthy body) was frequently used in these manuscripts to indicate that the authors were strong advocates of seeking some kind of balance between the mental and physical education of new generations. They believed that more attention should be paid to physical education. This was thought to be not only in the interest of the individual but that of the state as well. By offering physical education in schools, the nation would be supplied with stronger and tougher youngsters eligible for safeguarding the borders of the country and colonies. At the same time, it would lead to “healthy-minded,” more social, hardworking, and disciplined citizens, which was also considered beneficial for the state. Another argument in favor of physical education in schools was that ancient folk games could be preserved for posterity this way.

While individuals promoted physical education in the Netherlands by means of writing books and articles, another powerful force was working in this direction in the first half of the 19th century: the Society for Public Welfare (in Dutch: Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen, hereafter referred to as MNA). This apolitical society, founded in 1784, is considered one of the most influential organizations to contribute to the intellectual disclosure of many rural communities and to the dissemination of elements of modern culture throughout the Netherlands. That public support for the MNA was substantial can be deduced from the fact that the number of so-called departments of the MNA grew from as few as 25 in 1795 to about 235 around 185027,28. Throughout the country, the MNA departments took responsibility for solving various social problems. They were engaged in promoting education for all citizens, building schools, improving learning methods, training teachers, giving lectures intended to educate people on all sorts of topics, founding libraries, etc.

The MNA also tried to counter prejudices against physical education and to get it admitted into the schools with the help of local and national governments. It played an important role in giving physical education a place within the curricula of primary and secondary schools, which is reflected in the Dutch education acts of 1857 and 1863. The MNA also organized prize contests to draw the attention of the people to the importance of physical education. From the 1840s onwards, the MNA established gymnastic schools in major cities out of its own pocket. Here, schoolteachers could also be educated to become gymnastic teachers.

Despite these endeavors, however, other circumstances had a negative effect on the speed of developments in physical education in the Netherlands in the first half of the 19th century. First, the social turmoil in Germany caused by developments in physical education, the so-called ‘Turnsperre’29, made Dutch authorities reluctant to stimulate initiatives in this area. Then there were practical problems that curbed physical education in its development, e.g., a shortage of teachers and accommodations and a lack of learning methods. The few teachers who could provide physical education lessons at that time originated mostly from the military30 – 31. Although they used foreign textbooks to acquire skills and specific knowledge, their lessons maintained a strong military character.

Growing Interest for Medical Gymnastics

With the ongoing discourse on the importance of physical education within the educational system, teachers and physicians gradually became more receptive to other views on how to use gymnastic exercises. In their classrooms and practices, they often were the first to be confronted with children who suffered from disabilities and illnesses. Since conventional medical interventions had little or no effect, the enthusiastic reports from Sweden and Germany must have led these teachers and physicians to believe that what was called “medical gymnastics” could be a remedy to cure these kinds of ailments.

R.G. Rijkens (1795–1855), a schoolteacher in Groningen, is thought to be the first to have implemented physical education in a primary school in the Netherlands (around 1839)31–34 (Figure 2). Not only did Rijkens strongly believe that it was of the utmost importance that children's minds and bodies should be developed in harmony, he was also one of the first teachers who pointed out the importance of gymnastic exercises as a treatment for certain diseases or disabilities. In 1843 he published an extensive book about physical education, the Practical Guide for Artificial Exercises of the Body for Families and Institutions of Education35. The first part of the book dealt with legitimizing physical education as an important element in the upbringing of children. The second part is a practical guide with a substantial section dedicated exclusively to medical gymnastics. Rijkens described a number of specific disorders and the exercises to treat them. Most of the exercises were derived from the work of the German physical education teacher J.A.L. Werner; others were chosen in consultation with a physician. Among the disorders likely to be cured by medical gymnastics the author listed “bended extremities, the clubfoot, weak ankles and feet, bended knees, limping, torticollis, squint, the narrow chest, and spine curvature deviations.” Rijkens emphasized that it was advisable to consult a “knowledgable physician” before starting to treat children with these kinds of ailments. Such a physician, however, should be informed about the latest developments where diagnoses and (gymnastic) treatment were concerned. Noteworthy is the fact that Rijkens allocated a merely advisory task to physicians, whereas schoolteachers by profession were supposed to point out the children who were in need of treatment and subsequently, to take care of this treatment. It is very likely that Rijkens treated children with medical gymnastics himself.

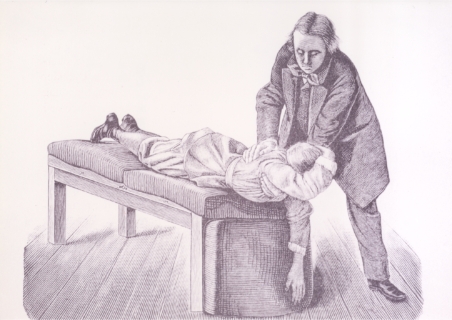

Fig. 2.

Roelof Gerrit Rijkens (1795–1855) and his ‘practical guide’ (1843) (Sources: Stichting Iconographisch Bureau Den Haag and Rijkens RG. Praktische Handleiding voor Kunstmatige LigchaamsOefeningen, ten Dienste van Huisgezinnen en Verschillende Inrigtingen voor Onderwijs en Opvoeding. [Dutch for: Practical Manual for Artificial Physical Exercise for Families and Educational Institutions]. Groningen, the Netherlands: J. Oomkens, 1843.)

At this time, around 1840, no reports on treatments with medical gymnastics had yet been published in the medical journals. This would change in less than 10 years. In the 1840s, a group of young progressive physicians appeared on the stage and called for reforms in medicine. Some of them were referred to as “hygienists' (in Dutch: hygiënisten)36. These Dutch sanitary reformers were an important element in bourgeois radicalism, which saw the European revolutions of 1848 as a critical context for general socio-political change. They played an important role in the founding of the Dutch Society for the Promotion of Medicine (in Dutch: Nederlandsche Maatschappij tot bevordering der Geneeskunst, hereafter referred to as NMG) in 1849, and they were very active in many local and national organizations concerned with healthcare. Furthermore, they held positions on the editorial boards of various renowned medical journals. Dissatisfied with their own social status and with the poor health of the population, the hygienists advocated better public health, which was sought through improving houses, schools and other buildings, sewer systems, waterworks, and so forth. According to them, physicians should supervise all these activities themselves. Because personal hygiene had a place on their agenda as well, they also showed an interest in the possibilities of physical exercise to raise the standard of the physical well-being of the population and to combat various diseases and forms of disablement. Between 1848 and 1865, an increasing number of articles on pedagogical and medical gymnastics were published by these hygienists in medical journals.

An example is the 1849 article “Announcements Concerning Kinesitherapy” by the hygienist J. Bosman Tresling (1803–1881)37. According to this physician from the city of Groningen, it was the first article of its kind published in the Netherlands. The 36-page article concerned itself only with medical gymnastics and is based mainly upon the publications of Ling's disciples Georgii and Rothstein38, 39. Bosman Tresling elaborated on the gymnastic system of Ling and extensively reviewed publications by German physical education teachers and physicians. He emphazised that, where physical education teachers had been playing a major role in developing, implementing, and writing about medical gymnastics in the first half of the 19th century, Dutch physicians had not paid much attention to this relatively new form of medicine yet. Three years later Bosman Tresling published another long article on this matter, entitled “New Announcements Concerning Kinesitherapy”40. This time he based his article mainly on the publications of the German physicians A.C. Neumann, M.M. Eulenburg, and D.G.M. Schreber, to whom he referred as “kinesitherapists.” Again he elaborated on different ways of treating various diseases and deformities with medical gymnastics (including massage).

Physicians like Bosman Tresling would not only write articles about medical gymnastics. From the 1850s onwards they gave lectures on the subject as well41 – 42. As in their articles, they stated that proper treatment by means of medical exercises could only be provided by persons who were skilled physical education teachers as well as skilled physicians. The problem was that those persons did not (yet) exist. The physical education teachers who were active in the field of medical gymnastics in the 1850s were not formally educated/trained in this direction. The same applied to physicians in this period. In university curricula, no attention whatsoever was paid to this kind of treatment. Physicians and physical education teachers, therefore, had to improve their skills while treating patients (learning on the job) and educate themselves by reading foreign, mostly German, articles and textbooks on the subject. This would remain the case throughout the second half of the 19th century. There was yet another strategy to improve one's skills and knowledge: to visit institutions abroad run by those who were considered to be the experts in medical gymnastics. Well documented are the travels to practices in several neighboring countries undertaken by the Amsterdam physician and city orthopaedist J.L. Dusseau (1824–1887) and the physical education teacher J.G. Milo Jr. (1840–1921) (Figure 3).

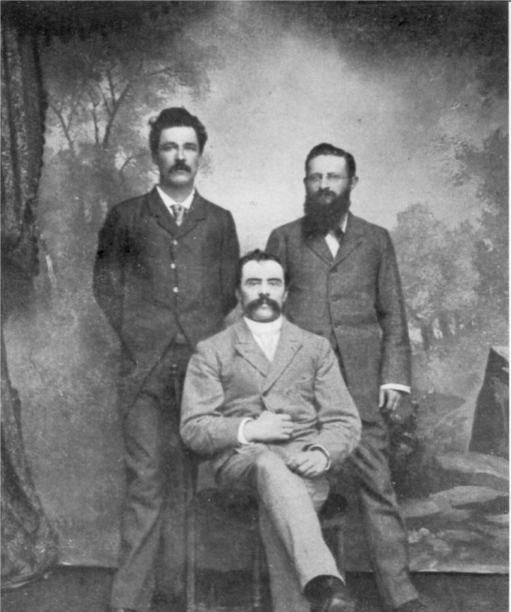

Fig. 3.

City Orthopaedist Dr. Justus Lodewijk Dusseau (1824–1887) and Physical Education Teacher J.G. Milo Jr. (1840–1921). Pioneers in the field of heilgymnastics (Sources: Vereniging Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde and Bakker, LF. Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging 1898–1998. De Geschiedenis van de Orthopaedie in Nederland. [Dutch for: The Dutch Orthopaedic Association 1898–1998. The History of Orthopaedics in the Netherlands]. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: NOV, 1998.)

The Practice of Medical Gymnastics Before 1860

After 1850, an increasing number of medical journal articles mentioned persons active in the field of medical gymnastics. In the 1858 Medical Journal (in Dutch: Geneeskundige Courant), for example, the physical education teacher C.A.J. de Gruyter from Deventer reported on treatments with medical gymnastics he had given to patients since 185543. The disorders he claimed to treat included St. Vitus dance, headaches, congestions, contractions menorrhoea and defecation problems, and nosebleeds. His treatments were mainly based on what he had learned from the publications of the German physician D.G.M. Schreber.

Also active in the field of medical gymnastics before 1860 were the already mentioned Amsterdam city orthopaedist Dusseau and some physical education teachers who were treating groups of children suffering from various deformities and illnesses in the special school for gymnastics that was founded by the Amsterdam Department of the MNA4. One of them was the physical education and fencing teacher J.G. Mezger (1838–1909) (Figure 4). In the 1850s, he worked closely with Dusseau, who must have introduced him to Swedish medical gymnastics30. Not long after taking the exam to become “a domestic physical education teacher” (1859), Mezger resigned as a teacher and went to Leiden to study medicine in 1860. In 1868 he finished medical school and in the same year he got promoted after defending his thesis The Treatment of Distorsio Pedis with Frictions44. Finally, in 1870, he passed the exam to become a physician. He treated many people in the 1870s and 1880s in his flourishing practice in the Amstel Hotel in Amsterdam. Massage seems to have had Mezger's interest. He received credit from many authors for bringing massage back to the attention of the medical profession in the 19th century45.

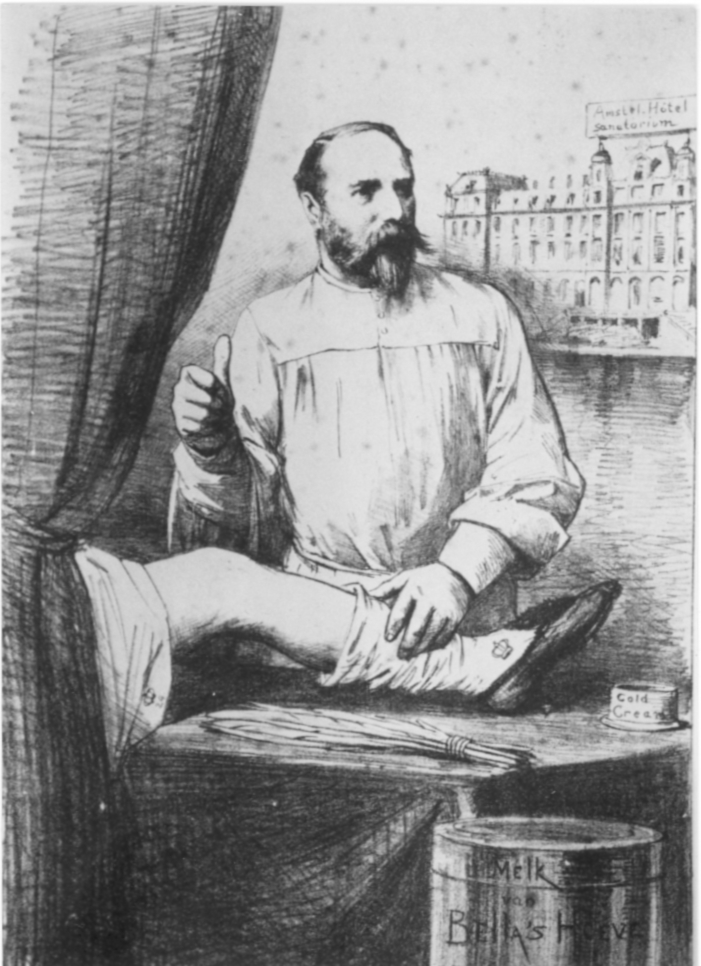

Fig. 4.

Physical education teacher and physician Johan Georg Mezger (1838–1909) who frequently treated royalty in the Amstel Hotel (Source: Kostelijk PJ. Dr. Johann Georg Mezger—1838–1909—en Zijn Tijd. [Dutch for: Dr. Johann Georg Mezger—1838–1909 and His Time]. Leiden, the Netherlands: Universitaire Pers, 1971).

Other physical education teachers at the MNA gymnastics school in Amsterdam who engaged in treating people with medical gymnastics were M.A. van der Est, who eventually started his own practice elsewhere in Amsterdam where he treated patients with electrotherapy in addition to medical gymnastics, J.S.G. Disse, J.A. van Monsjou, and J. Pieters33, 46, 47.

By then, it was clear that the institutionalization of medical gymnastics was taking place within both the domains of physical education and medicine. In Sweden and Germany, and to a lesser extent in France and the United Kingdom, this situation led to tensions between both groups of professionals, as noted by Dusseau in 185848. In the Netherlands, however, signs of such tensions were not found in the periodicals and books before 1860.

The Rise of Medical Gymnastics, 1860–1889

New Legislation Concerning Education and Healthcare

With an upcoming Liberalism, an emancipated citizenry, and changing economic structures in the Netherlands around 1850, a new era presented itself. Along with it came a strong need for a kind of education that would meet the changed demands of time; i.e., it should be more directed towards solving practical problems in modern economic life and eventually raise the standard of living of all. Furthermore, it should enable the new generations to stimulate trade, industry, and agriculture in order “to put the Netherlands on the map” again. After the revision of the constitution in 1848, several changes were made in the legislation concerning education. In 1857, the new Primary School Act, which was intended to improve the education at the lowest level, was passed49. In 1863, this act was supplemented with the Secondary School Act and in 1876 with the Act for Higher Education50 – 51.

The Primary School Act allowed primary schools to give physical education lessons as an official part of their curriculum. Consequently, because primary school teachers had to be educated in this direction, more attention was paid to the theory and didactics related to physical education. This development got an extra impulse when the Secondary School Act went into effect in 1863, during the second cabinet period (1862–1866) of the Liberal Prime Minister J.R. Thorbecke (1798–1872). This act stated that pupils should be given a broad general knowledge base. Among the new school types established, where this kind of education should be implemented, was the Higher Citizen School (in Dutch: Hogere Burgerschool [HBS]). Pupils had to take 14 to 18 subjects, and each of these subjects was to be given by specialized teachers. Because physical education was one of the obligatory subjects, qualified teachers in this field were needed as well. To meet this demand, the Secondary School Act provided for special exams that were organized once a year by a special committee. This development led to the emergence of a new group of professionals. Mainly members of this group who would engage in medical gymnastics in the second half of the 19th century.

During the period 1842–1862, different state committees revised the legislation in the healthcare domain that had originated in 1818. This eventually led to the acceptance by Parliament of the four Medical Acts of Thorbecke in 186552–55. Objectives of these acts were, among other things, to improve the control of the state with regard to preventing the outbreak of disease and the implementation of hygienic measures, to reduce the variety of medical practitioners, to organize the education and licensing of the different professions within this domain, and to abolish quackery.

Although some of the ideas of the hygienists and other progressive physicians were not quite honored, these medical acts were quite favorable towards the members of the medical profession. The once great number of varied medical practitioners was eventually reduced to only one: the physician (in Dutch: arts). To become a physician, one had to take two state exams and meet several other specific conditions. Once a physician, one was ensured a high degree of autonomy in his practice. It was laid down legally that physicians themselves could define their profession (what is medicine?), they could decide how they would run their practice (which therapy and how it should be applied?), and they could determine what the results of their actions would be (what constitutes illness/health?)56. In effect, the new physician actually was granted a monopoly in the field of healthcare with these medical acts. Only he who was authorized by law was allowed to practice medicine and to make this publicly known. Although the underlying thought of the Dutch government was to combat quackery, these laws unintentionally led to a situation in which it would become very hard, if not impossible, for new occupations to establish themselves in the healthcare domain57. One could say that the medical acts of Thorbecke came too soon for the new professionals, who were active in the field of medical gymnastics: the cake of the healthcare domain had de facto been cut and parcelled out in 1865.

After the Higher Education Act of 1876 came into effect, several regulations followed in the late 1870s and early 1880s in medicine that placed the education and examination of physicians solely in the hands of the medical faculties at the universities. Twenty years after the medical acts of Thorbecke, physicians had succeeded in gaining control over the recruitment, education, and examination of future colleagues. Apart from obtaining a relatively high level of autonomy with regard to their practice, physicians now enjoyed a legally sanctioned autonomy with regard to their education as well.

Practice of Medical Gymnastics after 1860

In the second half of the 19th century, interest in the application of medical gymnastics, more and more referred to as “heilgymnastics” (in Dutch: heilgymnastiek), increased. It was considered a “relatively new and very promising field in medicine” by physicians. While new legislation with regard to physical education and medicine was prepared and came into effect, heilgymnastics was already being practised in several places in The Netherlands. Those who engaged in such activities who were not physicians were referred to as “heilgymnasts” (in Dutch: heilgymnasten).

From data derived from seven renowned medical journals and five physical education journals between 1860 and 1889, we learn that an increasing number of people were interested and active in the field of heilgymnastics4 (Figure 5). The number of articles that explicitly deal with heilgymnastic treatments doubled every decade (1860–1869: 10, 1870–1879: 26, 1880–1889: 48). When we take everything into account that is written in both types of journals (not only articles and reviews, but advertisements, messages, etc., as well) and look at the status of those who are mentioned in relation to heilgymnastic activities in the same three decades, we can see that there was an increase in references regarding the activities of non-physicians (1/9/25). Also, physicians seem to have been much more active in the 1880s than before (2/1/10). The combined activities of physicians and non-physicians were reported as well (1/11/6). In these references, it seems that heilgymnasts were in charge of the actual treatment whereas the role of physicians was described as charged with the supervision or having referred their patients or having consented to a treatment or having a consulting role.

Fig. 5.

Example of a heilgymnastic treatment (Source: Schreiber J. Praktische Anleitung zur Behandlung durch Massage und methodische Muskelübung. [German for: Practical Guide for Treatment with Massage and Systematic Exercises]. Wenen/Leipzig, Germany: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1888).

In addition to physicians and heilgymnasts, another group of people was active in the field of heilgymnastics in the period 1860–188946,58. In the periodicals, these were referred to as “quacks” (in Dutch: kwakzalvers) or “bunglers” (in Dutch: beunhazen). They were described as incompetent (i.e., having no education whatsoever) and accused of seeking opportunities to earn money in the easiest possible way. It seems that the more popular heilgymnastics became over the years, the bigger this group grew. It is impossible to say, however, exactly how many bunglers there were and where they were active. Until further evidence is presented, it is presumable that they constituted a minority among those who were actively engaged in heilgymnastics.

The vast majority of the ailments that were treated with heilgymnastics consisted of deformities of the spine, chest, shoulder blades, and limbs. Paralysis, bad innervation, insufficient breathing, neuralgia, chorea minor, gout, rheumatism, headaches, chlorosis, scrophulosis, tuberculosis, adipositas, and general weakness are also mentioned as indications for treatment.

Heilgymnastic treatments were mainly given in the major cities, especially in the western provinces of North-Holland and South-Holland. Of these cities, Amsterdam seemed to have harbored most heilgymnastic activity. Of 64 references in total, 23 (36%) were related to the Dutch capital. Where the clientele of heilgymnasts is concerned, it appears that most patients came from the middle class, with a minority coming from the upper and lower classes. From extensive reports of two heilgymnasts, we learn that about 25% of their patients were children until 10 years of age, whereas people between 10 and 20 years of age made up 50% to 60% of the patients. The ratio of men/women was roughly 40/6059,60.

What did all those involved in heilgymnastics think about the situation at hand? What was, for example, the reaction of physicians to the fact that so many heilgymnasts were active in a field that was supposed to be a part of medicine? What were the thoughts of heilgymnasts on the presence of physicians in the field of heilgymnastics? How did members of both groups legitimize their professional activities in this field in the second half of the 19th century? How was this whole situation perceived by other relevant members of society?

Physicians Claim Heilgymnastics Exclusively for Themselves

As we have seen, among physicians the so-called hygienists were the most driven where it came to promoting and stimulating pedagogical gymnastics and the application of medical gymnastics since the 1840s. It was mainly due to their efforts and those of other young progressive physicians that new legislation in the field of education (1857 and 1863) and that of healthcare (1865) came into effect. These acts would have an enormous impact on the further development of medical gymnastics in the Netherlands. Although most of the hygienists were not active in this field themselves, with their books, articles, editorials, lectures, and letters, they managed to make local and national authorities, physicians, and the public more receptive to this new and promising branch of medicine. It was generally considered supplementary to pharmaceutical and surgical therapies and seen as a successful way of treating certain disorders and ilnesses. Both pedagogical gymnastics, which was regarded as a part of hy-giene, and medical gymnastics, which was considered to lie more in the field of surgery, were believed to have a place within the curricula of the medical faculties61, 62. However, the role of the influential hygienists ended in the 1880s when most of them passed away. But other Dutch physicians began to take a strong interest in heilgymnastics, namely those who were specializing in the areas of orthopaedics and physical medicine.

In the 1880s and 1890s, a strong differentiation and specialization was going on within the field of medicine in the Netherlands. This led to fierce competition among groups of physicians for a position within the medical faculties and in the healthcare market. Surgeons who were specializing in orthopaedics began to claim this field exclusively as their own63 – 65. For these orthopaedists, it was essential to make clear to their peers and the outside world what orthopaedics stood for. Their definition of the field, which was for the most part inspired by German colleagues, included heilgymnastics; therefore, their claim on heilgymnastics grew stronger during the last two decades of the 19th century. The same was true for physicians who began to specialize in physical medicine, an up-and-coming field in the 1890s in the Netherlands.

An oversupply of physicians in the bigger cities in the western part of the Netherlands, as a result of the ongoing urbanization in the last quarter of the century, was responsible for this stronger medical claim of heilgymnastics as well. When the Netherlands was struck by an economic depression in the beginning of the 1880s, physicians felt threatened, not in the least by severe competition from their own colleagues66, 67. Since heilgymnasts, like physicians, mainly worked in the bigger cities, one can imagine that this extra competition in the healthcare market was not welcomed at all. Physicians feared and suffered a loss of income because of these practioners. Therefore, they readily gave support to the orthopaedists' claim that heilgymnastics, which was defined as a form of conservative medical treatment, should be the exclusive terrain of physicians.

Of course, physicians did not mention these less noble motives when claiming the field of heilgymnastics. Like many before them, they legitimized their claim by pointing at the healthcare and university acts of the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s. After all, the monopoly in healthcare that had been granted by the legislation in 1865 enabled them to define the extent of their domain as they pleased. Furthermore, they stated that practising heilgymnastics—an important and effective form of conservative medical treatment—should exclusively be entrusted to physicians since only they would know best—because of their medical education—how to best serve the interests of the suffering patient. It is noteworthy, however, that by the end of the 19th century, orthopaedists and other physicians regarded and discussed massage as a separate part of heilgymnastics and stressed that only massage was the exclusive terrain of physicians63, 67 – 69. Were they claiming only this part of heilgymnastics because they were aware of the fact that the legal basis for claiming the whole of heilgymnastics (including massage) was too weak4?

At first, the claims and the protests against the activities of heilgymnasts came mainly from individual physicians who published letters and articles in periodicals, but in 1888 the Dutch Society for the Promotion of Medicine (NMG) took a stand in this matter as well. The NMG asked the national government to take proper measures to prevent unauthorized persons from being active in the field of orthopaedics and massage by means of a better use of the punitive measures as mentioned in the medical laws70 – 72. However, no action was ever taken by the government.

Despite the claim of orthopaedists and other physicians and the request of the NMG, the practice of heilgymnastics in the Netherlands remained mostly in the hands of physical education teachers and others, with or without the supervision of a physician. Only a few physicians seemed to have been active in this field, e.g., S.B. Ranneft (1852–1909) and J.A. Korteweg (1851–1930) from Groningen, W. Renssen (1856–1917) from Arnhem, and C.B. Tilanus from Amsterdam46, 73. One could say that a tension existed between the physicians' growing claim on heilgymnastics (on a theoretical level) and their not wanting to actively engage in this field (on the practical level). Why were so few physicians active in this field?

One reason may be that in this period, most physicians were more interested in specialized clinical curative medicine than in “rather simple and old-fashioned healing methods,” such as heilgymnastics45. Attention within the curricula of the medical faculties was directed mainly towards those subjects that could strengthen the scientific basis of medical clinical practice (physiology, chemistry, histology, bacteriology, etc.). Consequently young physicians were not acquainted with heilgymnastics during their education and thus remained unfamiliar with it. Another reason may be that physicians perceived practising heilgymnastics as very labor-intensive: one had to give long and strenuous therapy sessions and treatment could go on for months. In addition, when compared to issuing pharmaceutical drugs for example, giving a heilgymnastic treatment would mean making less money and having to work much harder for it, not a very appealing perspective (Figure 6). The fact that physicians may have looked down on practising this “craft,” because it did not comply with their self-image as “men of science” may have played a role in this respect as well.

Fig. 6.

Example of a heilgymnastic treatment (Source: Schreiber J. Praktische Anleitung zur Behandlung durch Massage und methodische Muskelübung. [German for: Practical Guide for Treatment with Massage and Systematic Exercises]. Leipzig, Germany: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1888).

Increasing Number of Physical Education Teachers Active in the Field of Heilgymnastics

As noted, the biggest group active in the field of heilgymnastics were physical education teachers. In the period 1857–1879, about 140 persons, of whom 15 were females, were licensed as secondary school physical education teachers (Act of 1863), while 1160 people, of whom 60 were females, became qualified to give physical education lessons in a primary school (Act of 1857). These numbers increased rapidly during the 1880s74 – 77. It is not known how many of these professionals actually engaged in heilgymnastic activities, but the impression is that they formed a minority within the population of physical education teachers.

The fact that physical education teachers became active in this field is understandable, considering the history of the introduction of heilgymnastics in the Netherlands described earlier. From the beginning, these professionals were taught that heilgymnastics was a part of the greater physical education system. During their—mostly autodidactic—studies, physical education teachers were confronted with theories and case studies regarding the application of heilgymnastics and so became acquainted with it at an early stage of their careers. To practise in the field of heilgymnastics, they needed many of the skills that were also required for teaching gymnastics, their actual field of competence. They knew much about how to teach people certain movements, about different types of exercises, about the materials that could be used to perform these exercises, and so forth. Thus, from this technical point of view, it seems to have been a small step for physical education teachers to start working in this new field. Although physical education teachers as well as physicians stated they were able to apply heilgymnastics, most of them were at the same time aware that they were lacking essential knowledge and skills78 – 81. In the 1860s and 1870s, many pleas appear in the periodicals in which improving the education of the physical education teacher as well as that of the physician in this respect is advocated81 – 83.

Another factor that stimulated the involvement of physical education teachers in the field of heilgymnastics was their position as schoolteachers. In this capacity they were confronted with children suffering from some kind of illness or disablement, and more than once they would have witnessed that these children did not receive any treatment or were treated with braces, corsets, and the like without much effect. This may have given them the idea that heilgymnastics might be more successful in these instances. The fact that physicians did not engage in heilgymnastic treatments could have been an extra stimulant for physical education teachers to start treating these children themselves81, 84. Scientific curiosity as to the effect of exercises but also altruism and social concern may have played a role in this as well.

There were also other motives that drove physical education teachers to become active in heilgymnastics. Here we refer to some awkward circumstances characterizing the field of physical education in the Netherlands at this time. The inadequate organization of the gymnastic exams85 – 87, a shortage of proper teaching methods and training schools4, 88, and a lack of research facilities and a forum for exchanging experiences89 – 91 were all circumstances that caused a lot of frustration and forced physical education teachers to acquire their skills and knowledge mostly in an autodidactic manner4, 92. These factors had an obvious negative effect on how physical education was regarded.

Other circumstances cast a shadow on the status of the physical education teacher as well. For one thing, these teachers had to put up with bad working hours, because for many school principals and other authorities, physical education was just not important enough93, 94. Therefore, pupils had to take these classes—if at all—very early in the morning or in the late afternoon and early evening33, 95 – 97. Furthermore, children of various ages were often put together to receive physical education lessons for reasons of convenience, which made these lessons difficult to give33. Also the fact that, despite many pleas of physical education teachers, physical education still was not part of the final exams in the secondary schools had a negative effect on how physical education was perceived98. And last but not least, compared to other teachers, physical education teachers at the time had the lowest salary, which often forced them to take on different odd jobs next to teaching to be able to maintain a certain standard of living33, 34, 96, 99, 100. Treating people with heilgymnastics was one such job. Apart from economic reasons, these professionals may well have thought that this would also boost their status. By practising heilgymnastics, they would be active in the field of medicine, a field of science that was looked upon with much more respect.

Organizations in the Field of Physical Education Abolished Heilgymnastics

Many tried to improve the situation in physical education. The hygienists, not only as individual physicians, but also as members of different medical advisory and control boards, had tried to elevate the level of physical education in the Netherlands in the period 1840–18904,101,102. The two most important organizations in the field of physical education, the Association of Physical Education Teachers in The Netherlands (in Dutch: Vereeniging van Onderwijzers in de Gymnastiek in Nederland), founded in 1862, and the Dutch Physical Education Confederation (in Dutch: Nederlandsch Gymnastiek-Verbond), founded in 1868, also tried very hard to improve the circumstances in this field31, 103. During the 1880s, however, when the domain of heilgymnastics became more and more disputed, these organizations had great difficulty taking a stand in the discussion: Should heilgymnastics be regarded as an extension of pedagogical gymnastics (and therefore belonging to their field of professional interest) or as a part of the medical discipline (and thus off limits for them as non-physicians)? In the middle of the 1880s, the organizatons took a strategic stand and decided to consider heilgymnastics as a separate discipline, thus separate from physical education (pedagogical gymnastics), and they agreed to serve only the interests of physical education in general and the interests of its schoolteachers in particular104. This decision of the executive committees of the physical education organizations had everything to do with the deplorable circumstances under which physical education teachers were being educated and performing their duties in schools and with the low position of physical education in the professional hierarchy of education. There was still a lot to strive for in the area of pedagogical gymnastics, and the executive committees were aware of the fact that in order to improve the situation, they were very much dependent upon the support of physicians, many of whom occupied seats on municipal committees and boards of organizations that had a say about the future of different aspects of physical education. The organizations of physical education just didn't want to run the risk of getting into conflict with physicians. Their new policy meant a major setback for the relatively small group of heilgymnasts/physical education teachers who wanted to promote heilgymnastics. The effect was an immediate decrease in the number of publications on heilgymnastics in physical education journals. It also led, after fierce discussion among physical education teachers, to the abolition of subjects like orthopaedics and healthcare in meetings and in certification examinations for physical education teachers105 – 107.

The physical education teacher G.J. Mullers probably expressed the feeling of many colleagues in 1885 when he wrote that he was convinced that a discussion about treating “orthopaedic” disorders in a meeting of physical education teachers was not in the interest of the profession and its organizations90. He argued that the certificate as an examined physical education teacher did not give any guarantee that one had acquired sufficient knowledge and skills in the field of heilgymnastics. The opinion and skills of a physician were, therefore, the only things to hold on to in this respect. That was to say, unless someone had made an intensive study of heilgymnastics and had acquired a great experience treating people with it, he had no right to speak and act in these matters. To solve the problematic “heilgymnastic issue,” Mullers advocated installing a state-exam for heilgymnastics. Then the public could be assured that they were dealing with real professionals in this field. Furthermore, he wrote, if physical education teachers wanted to be active in this field, they should found an organization of their own that would look after their special interests. He even called this a matter of great urgency.

The Legislature, the Public Health Inspectorate, and the Judicial System

We have seen that the domain of heilgymnastics was a matter of controversy within the world of physical education and medicine throughout the second half of the 19th century. In the late 1870s and 1880s, the discussion of who was to treat patients with heilgymnastics became more grim in medicine and physical education periodicals. In the middle of the 1880s, physical education teachers became divided over the question of whether heilgymnastics belonged to the domain of physical education, while the organizations in the field of physical education decided to drop the heilgymnastic issue from their agendas altogether for political reasons. At the same time, physicians claimed this domain more rigorously than ever before and even the NMG took a clear stand on this matter. The question arises how the national government dealt with the situation at hand. Didn't the legislature issue various laws during the second half of the 19th century that were to regulate the activities in these fields? When noticing that things did not function the way they should, was it not up to the members of Parliament to address the government with the question to do something about it?

During the second half of the 19th century, both local and national governments kept a low profile in this respect31, 103, 108, 109. In the archives of the national government, nothing is found with regard to heilgymnastics. It seems that either the problems with regard to the “new” heilgymnastic domain were not recognized by the members of Parliament or they were thought of as not important enough to spend time on.

What did the Public Health Inspectorate (in Dutch: Geneeskundig Staatstoezicht) undertake with regard to the heilgymnastic activity of non-physicians? The tasks of the Public Health Inspectorate, installed by one of the medical laws of Thorbecke in 1865, were to investigate where and how public health was threatened, to advise as to how these problems could be solved, and to guard the maintaining of healthcare laws and other regulations. In the period 1866–1902, reports were published each year in which the different divisions of the Inspectorate gave an account of their activities on behalf of the crown (in Dutch: Verslag aan den Koning van de Bevindingen en Handelingen van het Geneeskundig Staatstoezigt). From these reports, we learn that the heilgymnastic domain was an issue several times over the years4. The inspectors and advisory boards of the Public Health Inspectorate were aware of the problematic situation concerning heilgymnastics, but they knew that under the ruling laws they could not do very much against physical education teachers who engaged in heilgymnastic activities. Nevertheless, they kept warning these heilgymnasts, threatening with prosecution for breaking the (medical) law.

The heilgymnasts, on their part, just continued their work and could not be bothered with these kinds of threats. During the period 1865–1889, only a few of them were actually brought before the judicial system. As far as the records show, only one physical education teacher was ever sentenced with a fine because he had given a massage110. Although the inspectors and advisory boards of the Public Health Inspectorate acknowledged that something had to be done about the situation, they did not know how to proceed. For a while, they believed an improvement could come from changes in the educational system of physicians or physical education teachers, but they soon found that there was no political basis (among physicians) for such a solution.

The Founding of Organizations in the Field of Physical Medicine

During the last decades of the 19th century, the process of industrialization intensified in the Netherlands111. With it came an increase of migration, urbanization, competition, commercialization of social relations, and a loss of importance of traditional institutions (i.e., secularization). From the 1880s onwards, there was a tremendous growth of political movements and societies for various activities and strivings. The more people felt isolated and threatened in their rapidly changing world, the more they sought refuge in these societies. At the same time, the end of the 19th century was a time of opportunity, of emancipation. There was an increase in vertical social mobility, not only because of economic changes but also due to more and better education for all layers of the population. Among the groups who wanted to emancipate were the heilgymnasts. Ten years before physicians specializing in orthopaedics and physical medicine founded organizations dedicated to these fields, heilgymnasts organized themselves.

The Society for Practising Heilgymnastics in the Netherlands

In July 1889, two physical education teachers and heilgymnasts, E. Minkman (1848–1912) and J.H. Reijs Jr. (1854–1913), sent a circular to nine of their colleagues with an invitation to attend a meeting112. They wrote that heilgymnasts should unite in solving the problems that the field of heilgymnastics was facing. The many different ways to treat patients with certain disorders called for a thorough analysis to separate the good treatments from the bad. No practitioner was believed to be capable of doing this all by himself. Another problem was the increasing number of bunglers who worked in this field. Reijs and Minkman wanted to make clear that heilgymnastics was not just a form of physical education and that further scientific education and a lot of practice were needed to become a good heilgymnast. They wanted to discuss all these matters and intended to found an organization to promote the theory and practice of heilgymnastics.

About a month later, on the first of September, seven heilgymnasts, all physical education teachers, assembled in a little cafe in Utrecht113, 114. Two other heilgymnasts could not attend the meeting but sent a letter in which they expressed their sympathy for this initiative. Both wanted to be registered as a member of the new organization. Two others did not want to join because of various reasons115. Those present at the meeting shared the concerns of the initiators with regard to the future of heilgymnastics and that of the heilgymnasts. All felt they were losing the overview with respect to the huge number of methods and systems of treatment. They too saw that it had become increasingly difficult for the individual heilgymnast to choose the right treatment for each particular patient. The absence of a specialized education facility and of a forum to exchange knowledge and experiences was seen as a major obstacle to the further development of their profession. There was a commonly felt need for legislation with regard to heilgymnastics: it should provide for exams, diplomas, and education programs (the initiators wanted an education for heilgymnasts on an academic level), while at the same time it should make it more difficult for bunglers to work in this field. The activities of these bunglers were seen as a menace to the reputation of the relatively new profession. They often were used as an example by those wanting to criticize the whole group of non-medical practitioners (heilgymnasts).

Improvement in these areas was to be expected neither from the professional organizations of physical education teachers nor from those of physicians. The heilgymnasts felt very uncomfortable with the fact that nothing had been done and, so it seemed, would be done about these problems by these organizations on their behalf. Especially from the physicians little help was expected. During the 1880s, the heilgymnasts had witnessed an increasing number of conflicts between members of the medical profession and those physical education teachers who engaged in heilgymnastic activities.

The heilgymnasts who covened in Utrecht strongly believed that a solid organization of serious, well educated, and well trained heilgymnasts could bring about a positive change. Such an organization could look after their interests much better (e.g., getting proper financial compensation for labor) and would enable them to elevate the professional level of the heilgymnasts. As intended, the meeting of the heilgymnasts resulted in the founding of the Society for Practising Heilgymnastics in the Netherlands (in Dutch: Genootschap ter beoefening van de Heilgymnastiek in Nederland, hereafter referred to as Genootschap). The Genootschap counted nine members. The two men who had taken the initiative, E. Minkman and J.H. Reijs Jr., were chosen to be the first chairman and secretary. H. van Kreel (1860–1921) was elected as treasurer (Figure 7). These three heilgymnasts constituted the first executive committee, which took on the task of writing the bylaws of the Genootschap. It made sure that the issues discussed during the first meeting were put down in these bylaws116. The aims of the Genootschap were described as follows: practising heilgymnastics and studying and developing the theory in this field; bringing about more uniformity in the ways of treating patients; and stimulating a good understanding between physicians and heilgymnasts.

Fig. 7.

The First Executive Committee of the Society for Practising Heilgymnastics in the Netherlands in 1889: J.H. Reijs Jr. (1854–1913), H. van Kreel (1860–1921) and E. Minkman (1848–1912) (Source: Maandschrift gewijd aan de Heilgymnastiek 1914;24:179).

The Genootschap provoked moderate reactions from organizations and practitioners in the fields of physical education and medicine during the first year of its existence4. Only the reaction that came from the editors of the Dutch Journal for Medicine (in Dutch: Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde) will be mentioned here. In three short reports they reported on the first two meetings of the Genootschap117 – 119. The emphasis in the second report lay with an issue that apparently was very important to physicians: the fact that the members of the Genootschap were held to the demand only to treat a patient after a physician had given his approval. The heilgymnasts of the Genootschap had put this requirement on themselves in order to create a good understanding between physicians and heilgymnasts (the third aim of the Genootschap). That there were good relationships between heilgymnasts and physicians and that some of the latter sympathized with the Genootschap can be deduced from the fact that several well-known Dutch physicians joined the Genootschap as special members and two German physicians, E. Fischer and J. Schreiber (1835–1908) and C.M. Nycander (1831–1909), who was educated at P.H. Ling's Central Gymnastic Institute in Stockholm and now active in Belgium, were listed as correspondent members.

The Quest for Legislative Recognition

Very soon, however, other physicians proclaimed again that the activities of the Genootschap were a threat to the process of differentiation and specialization that was going on in the field of medicine, especially with regard to orthopaedics and physical medicine. During the last decade of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th, competition in these areas became fiercer in the Netherlands. Physicians began to take an interest in heilgymnastics and other forms of physical therapy on a bigger scale. As the number of physicians increased around the year 1900 and working conditions for them, especially for those who had just started their practice in the bigger cities, became worse, the resistance against the position and activities of heilgymnasts and their organization increased. In an attempt to gain control over this particular field of medicine, five similar organizations were founded in this period by physicians who were active in physical medicine and orthopaedics (in both of these fields heilgymnastics was included): The Dutch Orthopaedic Association: The Association of Physicians for Practising Orthopaedics, Mechanotherapy, Medical Gymnastics and Massage (in Dutch: Nederlandsche Orthopaedische Vereeniging. Vereeniging van Artsen ter Beoefening van Orthopaedie, Mechanotherapie, Geneeskundige Gymnastiek en Massage) in 1898; the Dutch Association for Electrotherapy and Radiology (in Dutch: Nederlandsche Vereeniging voor Electrotherapie en Radiologie) in 1901; the Medical Association for Physical Therapy and Hygiene (in Dutch: Geneeskundige Vereeniging voor Physische Therapie en Hygiëne) in 1902; the Association for Physical Therapy (in Dutch: Vereeniging voor Physische Therapie) in 1903; and the Dutch Association for Thalassotherapy (in Dutch: Nederlandsche Vereeniging voor Thalassotherapie) in 1905.

The founding of the Genootschap in 1889 and these organizations around 1900 lifted the controversy over this portion of the health care domain between physicians and heilgymnasts from the level of a dispute between individuals in journals to that of a strategic friction between professional organizations. Both groups not only suffered competition from the other, but they had to put up with other competitors on the healthcare market as well. First of all, the number of bunglers kept rising. These people, often with no experience or knowledge of heilgymnastics, saw possibilities for themselves and tried to benefit from the increased popularity of heilgymnastics and the credulity of the public. Secondly, there was competition from often very young and inexperienced physical education teachers, who started to offer heilgymnastic services to the public immediately after they had obtained their qualification as a physical education teacher and sometimes after having attended only a very short course in heilgymnastics abroad. These youngsters were heavily criticized by the established heilgymnasts as well by physicians. Last but not least, the upcoming women's movement around 1900 and the consequences this had on the labor market (women of good standing were increasingly used by physicians to assist them in their heilgymnastic practices) gave rise to anxiety, especially among the members of the Genootschap.

According to the Genootschap community, all of these circumstances underlined the need for legislation in the field of heilgymnastics (with a state exam, a state diploma, and proper education). With legally sanctioned professionals, the public would know where to go and the physicians would know where to send their patients. From 1889 onwards, the members of the Genootschap tried to acquire the legal status for their profession in many different ways. It would take some 50 years, however, before heilgymnastics received the legal status they had ceaselessly strived for. During the German occupation in 1942, an act was sanctioned that stated that heilgymnastics was to be regarded as a “paramedical” rather than as a “medical” activity120. The act provided for criteria with respect to the training and examination of heilgymnasts.

Summary

Towards the end of the 19th century, physical medicine, a field that included mechanotherapy, hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, electrotherapy, light therapy, air therapy, and thermotherapy, became a contested area in the healthcare domain in the Netherlands. This was especially true for mechanotherapy, which consisted of exercise, manipulations, and massage, a form of therapy that had been documented as far back as the 1840s and used to treat disabled and chronically ill people with the aim to improve their functional ability. In contrast to what one might expect, mostly physical education teachers, soon referred to as heilgymnasts, dedicated themselves to this kind of treatment, whereas only a few physicians were active in this field. When groups of physicians began to specialize in the newly defined content areas of physical medicine and orthopaedics in the last quarter of the 19th century, they suffered heavy competition from these heilgymnasts and others. This became worse after the heilgymnasts organized themselves and founded the Society for Practising Heilgymnastics in the Nederlands in 1889. In the same period, differentiation and specialization processes within the medical profession led to fierce competition among groups of physicians for a position within the medical faculties and in the healthcare market. Although research on the developments in the field of physical medicine in the Netherlands in the late 19th and first half of the 20th century is still in progress, it seems plausible to suggest that the competition suffered on both fronts by these physicians had a negative impact on the academic development of physical medicine, orthopaedics, and heilgymnastics/physical therapy in the Netherlands during that time. Physical medicine couldn't truly manifest itself as a speciality within the medical profession in the Netherlands. From the 1920s onwards, physicians who specialized in physical medicine realized their speciality was “tainted” because of the activities of so many non-physicians in the field. These physicians gradually shifted their professional attention towards the up-and-coming specialities of orthopaedics, rheumatology, and, somewhat later, rehabilitation medicine. Compared to countries like Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, physical medicine in the Netherlands fell rapidly behind where scientific research was concerned. The practice of physical medicine was gradually taken over by heilgymnasts. Physicians increasingly granted them more freedom in using their own judgement when treating patients with physical therapies. In 1942, an act was passed in which the emerged division of labor in this field was confirmed, while control over diagnosis and treatment would remain an unsettled issue until new legislation came about in the 1990s.

As mentioned in the introduction to this article, choices were made to portray certain aspects of the development of physical medicine in the Netherlands. Research in this field is still in its infancy and studies published on this topic and related ones are scarce. Therefore, this article should be considered as a rough sketch of one piece of a puzzle of which the exact size has yet to be established. I would like to convey my sincere hope that more medical historians and other scholars will engage in historical and sociological research on physical medicine/physical therapy in their own country in order to get a better insight into this heavily neglected field of study. Only then we will be able to get a clear picture of the simularities and the differences in various countries and perhaps be able to make an effort to explain them. In due course I hope to be able to present further results of my research on developments in the field of physical medicine in the Netherlands from 1890 to 1942. As I was finishing this article, I received a dissertation written by Anders Ottosson in Sweden121. Although I was not able to understand the full text, as it was written in Swedish, from browsing through it and reading the English summary I've gotten the strong impression that this is a very interesting study that shows much resemblance to my own research. Contact has already been made to see if there is a possibility to work together on this topic. It is my hope that others will join us.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to Allen Mason from the Sheffield Hallam University, United Kingdom, and Hanneke van Denderen from the University Utrecht, the Netherlands, for reading and correcting earlier versions of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Licht S. History. In: Licht S, editor. Therapeutic Exercise. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Waverly Press; 1965. pp. 426–471. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krusen FH. Physical Medicine: The Employment of Physical Agents for Diagnosis and Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gritzer G, Arluke A. The Making of Rehabilitation: A Political Economy of Medical Specialization, 1890–1980. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terlouw TJA. De Opkomst van het Heilgymnastisch Beroep in Nederland in de 19de Eeuw. Over Zeldzame Amfibieën in een Kikkerland [Dutch for: The Rise of the Heilgymnastic Profession in the Netherlands in the 19th Century: On Rare Amphibians in a Country Full of Frogs] Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Erasmus Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terlouw TJA. Niets dan een handlanger, in alles aan den geneesheer ondergeschikt. Wederwaardigheden van zich emanciperende heilgymnasten in Nederland eind negentiende eeuw. [Dutch for: No more than an assistant, in all things subjugated to the physician: Experiences of emancipating heilgymnasts in the Netherlands at the end of the 19th century] Gewina. 1994;17:235–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terlouw TJA. Vervolgd wegens onbevoegde uitoefening der geneeskunst: Hendrik Soeter, heilgymnast te Groningen. [Dutch for: Prosecuted for unlawful practice of medicine: Henrdrik Soeter, heilgymnast in Groningen]. Gewina. 1995;18:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terlouw TJA. De opkomst van de heilgymnastiek. [Dutch for: The rise of heilgymnastics] In: de Knecht-van Eekelen A, Wiegman N, editors. Om de Verdeling van de Zorg. Beroepsprofilering in de Nederlandse Gezondheidszorg in de Negentiende Eeuw en Twintigste Eeuw. [Dutch for: On the Division of Care: Professional Profiles in Dutch Health Care in the Nineteenth Century and Twentieth Century] Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Erasmus Publishing; 1996. pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terlouw TJA. De opkomst en neergang van de Zander-Instituten rond 1900 in Nederland. [Dutch for: Rise and fall of the Zander Institutes around 1900 in the Netherlands]. Gewina. 2004;27:135–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terlouw TJA, Juch A. Orthopaedie als kunde en als kunst. Orthopeden en heilgymnasten: concurerende beroepsgroepen, 1880–1908. [Dutch for: Orthopaedics as a skill and an art. Orthopaedists and heilgymnasts: Competing professions, 1880–1908] In: Terlouw TJA, editor. Geschiedenis van de Fysiotherapie Gezien door Andere Ogen. [Dutch for: History of Physical Therapy Seen with Other Eyes] Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Aksant/SGF; 2004. pp. 67–108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terlouw TJA, Juch A. In het belang der lijdende mensheid. Pogingen van de Nederlandsche Orthopaedische Vereeniging tot uitschakeling van de niet-medische concurrentie, 1908–1942. [Dutch for: In the interest of suffering humanity: Attempts by the Dutch Orthopaedic Association to eliminate non-physician competition] In: Terlouw TJA, editor. Geschiedenis van de fysiotherapie gezien door andere ogen. [Dutch for: History of Physical Therapy Seen with Other Eyes] Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Aksant/SGF; 2004. pp. 109–172. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleich L. Dr Gleich's Physiatrische Schriften (1848–1858). [German for: Dr. Gleich's Discourse on Physical Medicine (1848–1858)] Munich, Germany: Franz; 1860. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossbach MJ. Lehrbuch der physikalischen Heilmethoden. Erste Hälfte. [German for: Textbook of Physical Therapies. Part One] Berlin, Germany: Verlag von August Hirschwald; 1881. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Risse GB. The History of Therapeutics. In: Bynum WF, Nutton V, editors. Essays in the History of Therapeutics. Atlanta, GA: Rodopi; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Krogt TPWM. Professionalisering en Collectieve Macht. Een Conceptueel Kader. [Dutch for: Professionalization and Collective Power: A Conceptual Framework] The Haag, the Netherlands: Vuga Uitgeverij; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernett H. Die pädagogische Neugestaltung der bürgerlichen Leibesübungen durch die Philanthropen. Beiträge zur Lehre und Forschung der Leibeserziehung. [German: The Pedagogical Metamorphosis of Civilian Physical Exercise by the Philantropists: Contribution to the Theory and Research into Physical Education] Schorndorf, Germany: Verlag Karl Hofman; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 16.GutsMuths JCF. Gymnastik für die Jugend. [German: Physical Education for Youth]. Schnepfenthal, Germany: 1793. [Reprint Frankfurt/Main: Wilhelm Limpert Verlag, 1970.]

- 17.McIntosch P. Physical Education in England since 1800. London, UK: G. Bell & Sons Ltd; 1974. [Google Scholar]