There are strong moves within Canada to make the Canadian health care system more like the US system by partially privatizing it. Those who favour this approach claim that the US system offers more choice and better quality of care and spares the public purse. Some proponents even go so far as to claim that it is more efficient. My purpose here is to disabuse Canadians of these myths by taking a close look at how the US system works and comparing it with the Canadian system.

In 1972 the Yukon Territory became the last jurisdiction in Canada to adopt the Medical Care Act, which set up a system to provide hospital and physician care to all Canadians.1 Before then, the Canadian and US health care systems were similar. Both were partly public, partly private, partly for profit and partly nonprofit. Both also left a great many citizens uninsured. The costs were also about the same — a little over $300 per person in 1970 — as were outcomes. At that time, life expectancy was about a year longer in the United States.2

But with the implementation of Canadian medicare, the 2 systems rapidly began to diverge in all respects. The US system became more and more costly, leaving increasing numbers of Americans — now about 46 million people — uninsured. In 2005, expenditures were twice as high in the US as in Canada — US$6697 per person v. US$3326 in Canada.3 And although Canada insures all its population for necessary doctor and hospital care, the US leaves 15% without any insurance whatsoever.4 Those who are insured often need to pay a substantial fraction of the bill out-of-pocket, and some necessary services may not be covered. In a recent survey, 37% of Americans reported that they went without needed care because of cost, compared with 12% of Canadians.3

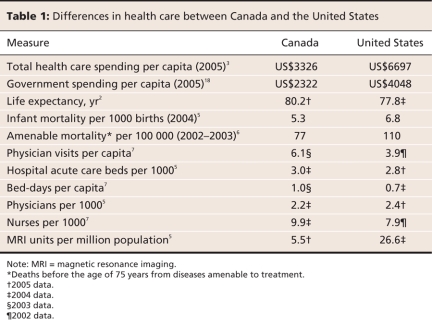

Outcomes also now favour Canada. Instead of living a year longer, the life expectancy of Americans is now 2.5 years shorter than that of Canadians.2 Infant mortality rates are higher in the US, as is preventable mortality (death before the age of 75 years from diseases that are amenable to treatment).5,6 Furthermore, contrary to popular belief, people in the US do not receive more health care services. They visit their doctors much less often and spend less time in hospital than Canadians do (Table 1). Per population, there are also fewer nurses and hospital beds in the US, although there are slightly more doctors and many more magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units.5,7

Table 1

Why the US spends more and gets less

The only plausible explanation for the US paradox of spending more and getting less is that the US health care system is enormously inefficient compared with the Canadian system. The inefficiency stems from the fact that the US, alone among industrialized countries, relies primarily on private, largely investor-owned corporations to provide health care.8 It is the only industrialized country that treats health care like a market commodity instead of a social service. Thus, health care is distributed not according to medical need but, rather, according to the ability to pay. There is a great mismatch, however, between medical need and the ability to pay. In fact, those with the greatest need are those least able to pay. Although markets are good for many things, they are not a good way to distribute health care because that is not their primary purpose. Businesses aim to increase revenues and maximize profits. Hospitals in the US, for example, often advertise their services. Like all businesses, they want more, not fewer customers — but only if they can pay. People who are wealthy or well insured may get an MRI they do not need, whereas those without insurance may not get an MRI they do need.

How the US system works

Most Americans under the age of 65 receive tax-free health benefits from their employers. Employers select the insurance companies and the plans to offer and pay a portion of the premiums — these days, a smaller and smaller portion. There is little choice. But offering benefits is strictly voluntary, and not all employers choose to do so. If offered, the benefits may not be comprehensive. Increasingly, employers cap their contributions, so that the burden of increasing costs falls on the workers.9 Employees, in turn, often turn down benefits when they are offered, because they cannot afford to pay their growing share of the premiums.

The private insurers with whom employers contract are mostly investor-owned, for-profit businesses. They try to keep premiums down and profits up by stinting on medical services. In fact, the best way for insurers to compete is by not insuring high-risk patients (called “cherry picking” or “cream skimming”), limiting the coverage of those they do insure (e.g., excluding expensive services, such as bone marrow transplantation) and passing costs back to patients as deductibles, copayments and claim denials. The US is the only country in the world with a health care system based on avoiding sick people. These practices add enormously to overhead costs because they require a great deal of paperwork. They also require creative marketing to attract the affluent and healthy people and to dodge those who are poor or sick. Not surprisingly, the US has by far the highest overhead costs in the world.5

It is instructive to follow the health care dollar as it makes its way from employers to the doctors and nurses and hospitals that provide medical services. First, private insurers regularly skim off the top a substantial fraction of the premiums (about 15%–25%) for their administrative costs, marketing and profits.9 The remainder is passed along a veritable gauntlet of satellite businesses that have sprung up around the health care industry. These include brokers to cut deals, disease-management and utilization review companies, drug-management companies, legal services, marketing consultants, billing agencies and information management firms. They, too, siphon off some of the premiums, including enough for their administrative costs, marketing and profits. It was conservatively estimated that, in 1999, 31.0% of all health care spending in the US was for overhead, nearly twice the estimated 16.7% in Canada. The overhead for Canada's private insurers that year was 13.2%, compared with only 1.3% for its public system.10

The most popular part of the US health care system is the government-administered system for Americans over the age of 65 — Medicare. This is a single-payer program embedded within the private, market-based system. It is by far the most efficient part of the US system, with overhead costs to government of about 2%.11 It covers virtually everyone over the age of 65, not just some of them. It also covers everyone for the full package of benefits, so it cannot be tailored to avoid high-risk or chronically ill patients. But US Medicare is not perfect, and it has been weakened by the Bush administration. Out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries are substantial and growing. Moreover, because Medicare pays for care in a market-based private system, it experiences many of the same inflationary forces that affect the private insurance system, including profit-maximizing hospitals and physicians' groups. In addition, doctors' fees are skewed to reward highly paid specialists for doing as many expensive procedures as possible. As a result, inflation in the Medicare system is almost as high as inflation in the private sector and is similarly unsustainable.8

Attempts to reform the US health care system incrementally have run into the following dilemma. If coverage is expanded, costs rise. If costs are controlled, coverage shrinks. This problem faces the US presidential candidates as they attempt to respond to the increasing calls for reform, and they have embraced opposite horns of the dilemma.12 Senator John McCain has opted for holding down costs by passing more of the burden to individuals, even though it means reducing coverage. Senator Barack Obama has opted for increasing coverage, even though it means adding to the staggering costs. Neither is a long-term solution. The only way to increase coverage and reduce costs is to change the system entirely.

Polls have shown that about two-thirds of Americans would prefer a Canadian-style system,13 as would three-fifths of doctors.14 However, many businesses that profit from the current system, mainly the private insurance industry and for-profit health care facilities, resist any fundamental change. They in turn have inordinate influence over law-makers and many economists and health policy experts, who propagate the myth that a Canadian-style health care system is “unrealistic.” In addition, many procedure-oriented specialists are quite happy with the current system. They are generally paid much more than they are in Canada, and that predisposes them to exaggerate the failings of the Canadian system and minimize those of the American system.

Strengths and failings of the Canadian system

In 1972, after the Yukon Territory signed on to the Medical Care Act, all Canadians were insured for physician and hospital services, but not for other health care needs such as home care, care in long-term facilities and prescription drugs. These and other benefits were left to the individual provinces, if they were covered at all. Moreover, many hospitals added user fees and doctors added extra charges. However, these practices ended with the 1984 Canada Health Act, which required, as a condition of federal contributions to provincial costs, that health care be accessible to everyone, and it essentially abolished user fees and extra charges.1 The system was able to keep costs in check in part by controlling the supply of certain services — for example, imaging and surgical facilities and the specialist physicians necessary to carry out the procedures. The result was the growth of waiting lists for some procedures. Nevertheless, Canadian medicare remained popular with the public — and still is.

During the 1990s, as Canada went through an economic downturn, Canadian medicare was underfunded. Waiting lists became a political issue, and public satisfaction with the system, although still high, fell somewhat. Toward the end of the 1990s, as economic conditions improved and the publicity about waiting lists increased, the provinces began to put more money into the health care system.1 But waiting times are still too long for certain elective procedures, such as hip and knee replacements, and it takes time for increased funding to be translated into more facilities and specialists.

The waiting lists are the ostensible reason for the pressures to partially privatize the Canadian health care system. I say “ostensible” because I believe the main reasons have to do with the desire of businesses and some specialists to profit from the system, just as they do in the US, and the desire of the federal and provincial governments to hold down their costs, even if it means increasing the burden on individuals. Lamenting waiting lists, however, sounds better to the public. In 2005, the Supreme Court of Canada handed down its decision in Chaoulli v. Quebec.15 It held that a 1-year wait for a hip replacement violated human rights guaranteed by the province of Quebec. Either Quebec would have to shorten waiting times or permit the procedure to be done privately. Although the effect in Quebec itself has been quite limited, the decision added force to a strong move throughout Canada, particularly in British Columbia and Alberta, to permit the marketing of private insurance and the delivery of care in for-profit facilities by doctors working in both the public and private systems. These facilities and doctors would be able to bill medicare and add extra charges.16

Why privatization is not the answer

Whether privatization would shorten waiting lists by creating more facilities is arguable. What it would certainly do is change who would be waiting. In the US, for example, well-insured patients have a very short wait for a hip replacement, but the 46 million Americans without health insurance might wait for the rest of their lives. As in all such parallel systems, privatization would draw off resources — physicians and other assets — from the public system.17 Waiting lists would be shorter in the private system, but they would almost certainly grow longer in the public system. Access would come to be more about money than medical need, just as it is in the US.

Moreover, it would not be a zero sum game. Money diverted to the private system would not buy the same health care as it would in the public system. There have been many studies comparing for-profit and not-for-profit health care in the US. For-profit care is nearly always more expensive and often of lower quality.8,18 Indeed, logic and common sense would suggest the same conclusions even without the growing empirical evidence. Unless we believe, without any evidence whatsoever, that for-profit organizations have some secret of efficient operation not known to the not-for-profits, it makes no sense to suppose that, given the same payment system and the same patient population, the for-profit organizations can provide similar services while still extracting their profits and business costs from the system. Neither does it make sense to imagine that investor-owned businesses are charitable organizations that wish to contribute their resources to the community. It is obvious that their responsibilities to their investors require them to take profits from the community. To do this, as many US studies have shown, they skim off the profitable patients and the profitable services, leaving the leftovers to the not-for-profits.

I would urge Canadians not to be swayed by the siren song of the privatizers. This is about profiteering as much as it is about health care. The same businesses that have made an exorbitantly expensive and unhealthy mess of the US system stand ready to do the same in Canada. The problem with Canadian medicare is not the system, it is the amount of money put into it. The US problem is exactly the opposite. It is not the money, it is the system. Those wishing to privatize the Canadian system often suggest that waiting times for hip replacements in the US are short because of the market-based system. That is not the case. In the US, most hip replacements are done in the public system for elderly patients. Thus, if we compare waiting times between the 2 countries, we are not comparing public and private systems. We are comparing 2 public systems, one of which (in the US) is better funded.

Canada's medicare is one of the best health care systems in the world — far superior to the US system. I would like to see it broaden its services to include long-term care, home care and prescription drugs. I believe it needs to be better funded from the public purse, although it does not require anywhere near the amount of money Americans put into their system. But it does fulfill its obligations to all Canadians by providing essential health care based on medical need, not on the ability to pay, and it has the great communitarian virtue of requiring everyone to be a part of the system.19 Thus, it matters to nearly everyone. Privatizing Canada's health care system, even a little, will inevitably cause costs to rise and access to decline. The wisest course for Canada is to expand and reinforce the public system, not undermine it.

Key points.

Health care costs per person are twice as high in the United States as in Canada.

The US health care system has worse outcomes, is less efficient and provides fewer of many basic services than the Canadian system.

The United States is the only industrialized country that treats health care as a market commodity, not a social service, and leaves uninsured those who cannot pay.

In the United States, for-profit health care is more expensive and often of lower quality than not-for-profit or government care, with much higher overhead costs.

The notion that partial privatization in Canada will shorten waiting times for elective procedures is misguided.

Partial privatization would draw off resources from the public system, increase costs overall and introduce the inequities of the US system.

The best way to improve the Canadian health care system is to put more resources into it.

Footnotes

This essay is based on a lecture presented at the joint meeting of the American and Canadian Orthopaedic Associations, Québec, Que., June 6, 2008.

Published at www.cmaj.ca on Oct. 6, 2008.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Marcia Angell, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, 13 Ellery Square, Cambridge MA 02138, USA; fax 617 576-7926; marcia_angell@hms.harvard.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Marchildon GP. Health systems in transition: Canada. Toronto (ON): University of Toronto Press; 2005.

- 2.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD health data 2008: statistics and indicators for 30 countries. Paris (France): The Organization; 2008. Available: www.oecd.org/health/healthdata (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 3.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, et al. Toward higher-performance health systems: adults' health care experiences in seven countries, 2007. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:w717-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.US Bureau of the Census. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States. Washington (DC): The Bureau; 2006.

- 5.American College of Physicians. Achieving a high-performance health care system with universal access: what the United States can learn from other countries. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:1-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:58-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Anderson GF, Frogner BK, Reinhardt UE. Health spending in OECD countries in 2004: an update. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1481-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Relman AS. A second opinion: rescuing America's health care. New York (NY): Public Affairs; 2007.

- 9.Geyman J. Do not resuscitate: Why the health insurance industry is dying and how we must replace it. Monroe (ME): Common Courage Press; 2008.

- 10.Woolhandler S, Campbell T, Himmelstein DU. Costs of health care administration in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med 2003;349:768-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Potetz L. Financing Medicare: an issue brief. Washington (DC): Kaiser Family Foundation; 2008. Available: www.medicareadvocacy.org/Reform_08_01.KaiserBriefReMAFinancing.pdf (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 12.Angell M. Health reform you shouldn't believe in: what the Massachusetts experiment teaches us about incremental efforts to increase coverage by expanding private insurance. Am Prospect 2008;May:A15-8.

- 13.Kuhnhenn J, Thompson T. Election 08 political pulse: the Associated Press/ Yahoo! news poll. The Associated Press; 2008. Available: http://news.yahoo.com/page/election-2008-political-pulse-voter-worries (accessed 2008 Aug 27).

- 14.Carroll AE, Ackerman RT. Support for national health insurance among US physicians: 5 years later. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:566-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Chaoulli v. Quebec (Attorney General), no 29272, Sup Ct of Canada 130 CRR (2d) 99; 2005 CRR LEXIS 76.

- 16.Steinbrook R. Private health care in Canada. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1661-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Flood CM. Chaoulli's legacy for the future of Canadian health care policy. In: Campbell B, Marchildon G, editors. Medicare: facts, myths, problems & promise. Toronto (ON): James Lorimer & Company Ltd.; 2007. p. 156-91.

- 18.Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Competition in a publicly funded healthcare system. BMJ 2007;335:1126-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Romanow R; Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada — final report. Ottawa: The Commission; 2002. Cat no CP32-85/2002E-IN. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/alt_formats/hpb-dgps/pdf/hhr/romanow-eng.pdf (accessed 2008 Sept 22).