Five years after the SARS outbreak Canada's public health system is being tested again, this time by food-borne listeriosis. The 16 deaths as of Sept. 15 that have been attributed to Listeria-contaminated food have already surpassed one-third of the number of deaths caused by SARS. The ultimate toll of the listeriosis outbreak is unknown because of the long incubation period and the possibility that cases remain undetected.1

The listeriosis outbreak allows for an examination of the effectiveness of the public health reforms that were intended to better prepare Canada for such public health emergencies.2 Such an examination exposes serious concerns about public health governance as well as the independence of the Public Health Agency of Canada and its lead official. It also raises the question of whether the system is functioning the way its architects envisioned.

The role of the Public Health Agency of Canada and the chief public health officer

The responsibility for the management of the listeriosis outbreak is divided between Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. However, there is a risk of confusion over which agency should be leading the management of the emergency. Each has distinct roles and responsibilities. Despite this division of responsibilities, though, it should still be expected that the Public Health Agency of Canada, and the chief public health officer, be the primary voice in communicating the health impact of the outbreak to the public.

The recommendations of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health3 stated that the chief public health officer should serve “as the leading national voice for public health, particularly in outbreaks and other health emergencies.” Such language is echoed in the Public Health Agency of Canada Act.4 However, the most visible figures in the recent recall of affected foods have not been public health officials but rather the head of Maple Leaf Foods and the minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Among the successes of the SARS outbreak were the daily updates provided on the extent of the outbreak and the clear leadership of Dr. Sheila Basrur, then Toronto's chief medical officer of health.5 So far, there has been no equivalent government official to guide the public through the listeriosis outbreak.

The listeriosis outbreak, which began just before the call for a federal election, clearly has to be handled carefully by a government that is concerned about its electoral success. Messaging concerning the competence of government oversight and the effectiveness of its policies with respect to preserving the health security of its population could be influential on the decisions of the electorate. This raises the question of the degree of independence of the chief public health officer, especially during specific points in the political cycle. In such circumstances, the ability of the officer to bring issues forward, or to comment freely on matters that may pose a risk to the public's health, may be particularly constrained. A similar question arises when examining whether the listeriosis outbreak could have been prevented and whether any changes in food inspection or regulations played an important role in the emergence of the outbreak.6 If this were the case, public health officials should have the authority to be able to identify such potential problems and bring them to the attention of the public and Parliament, without fear of repercussion.

The independence of the chief public health officer

Does the chief public health officer have complete independence to speak openly about public health matters or to identify shortcomings in the actions of other ministries that may pose a threat to public health? An important component of the perception that the chief public health officer may not be completely independent lies in the officer's role as a deputy minister who reports to, and serves “at the pleasure of,” the minister of health.7 Such concerns were identified in the SARS report,8 which stated that such an arrangement could “leave the Chief Public Health Officer in a rather awkward position as regards independently raising issues of broad concern for public health.” Although the option was considered of an arm's-length “surgeon general” type of position, the advantages of having the position ensconced within the bureaucracy favoured the creation of the current structure. However, the SARS report strongly suggested that safeguards be introduced to protect the chief public health officer's independence. Referring specifically to British Columbia's legislation, the report stated that the officer needs to have the authority to report independently to the public and Parliament.8

The Public Health Agency of Canada Act9 does provide some of this authority. In particular, it describes how annual reports are to be presented to Parliament and how the chief public health officer may communicate with the public “… for the purpose of providing information, or seeking their views, about public health issues.” The important question, however, is not simply what authorities have been given the chief public health officer but whether such authorities are coupled with employment protection. Although the officer may have the freedom to independently issue reports and communicate with the public, it is unclear how long a minister of health would tolerate an officer that appears to be acting orthogonally to the objectives of the ministry and the government. Because the chief public health officer serves “at the pleasure” of the minister of health, he or she can be removed at any time. The officer has also been exempted from the Public Service Employment Act and does not have the protection that other civil servants enjoy.7

In key contrast, Ontario's new Health Protection and Promotion Act, following the recommendations of Justice Campbell, provides independence from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and further protects the position by stating that “the Lieutenant Governor in Council may remove the Chief Medical Officer of Health for cause on the address of the Legislative Assembly.”10

Protecting the Public Health Agency of Canada and the public health system

A public health agency plays a critical role in safeguarding the public health security of the population. Such an agency must be able to function independently and communicate openly with the public and Parliament. It must be able to audit and comment on the actions of other government ministries to ensure that decisions are made for public health reasons and not for political or economic reasons. A public health system needs to be designed to protect against such compromises that are made intentionally or inadvertently.

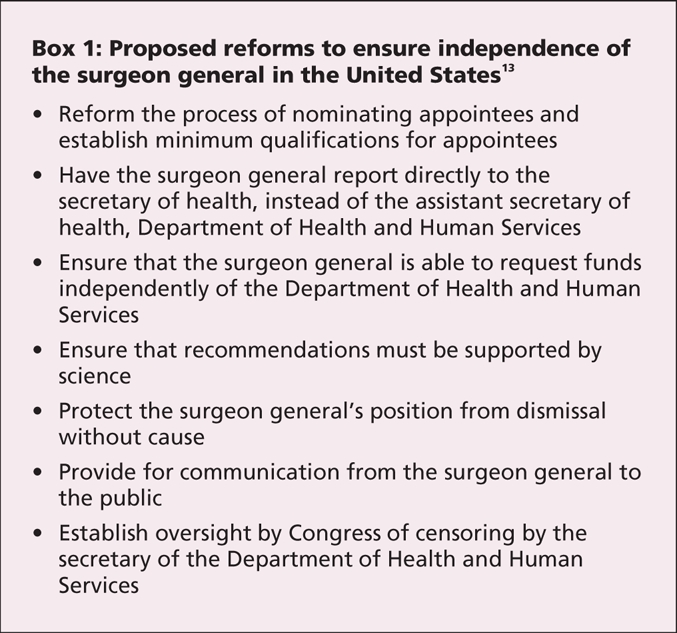

Similar problems have been found to exist in other countries. For example, former surgeon generals in the United States testified before the Congressional Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in 200711 that “Bush administrative officials repeatedly tried to weaken or suppress important public health reports because of political considerations.”12 Reforms have been proposed to provide the surgeon general with additional protection to act independently (Box 1).13

Box 1.

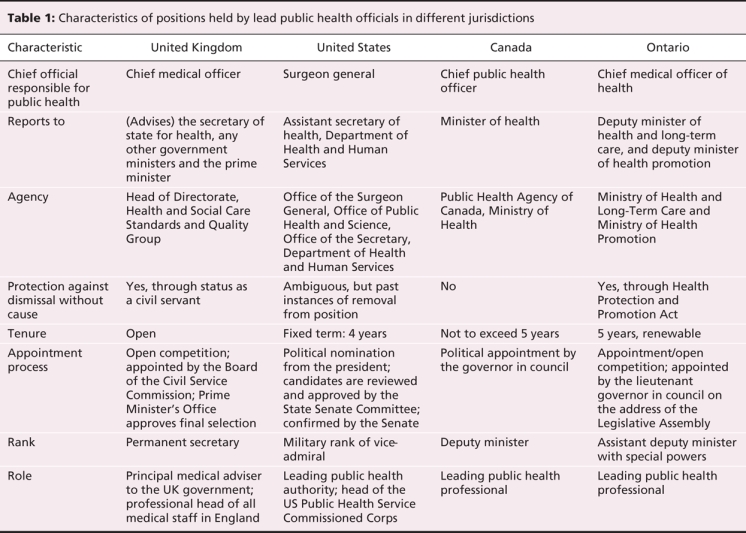

In contrast, in the United Kingdom, the position of chief medical officer of health was created with considerable protection of the officer's autonomy so that they are “not under political pressure to shape his or her advice in any given way nor to take any particular action that might be expedient but not in the public interest” (Table 1).14 However, the criticism after the bovine spongiform encephalopathy crisis was that critical information was withheld from the chief medical officer of health and the officer was sidelined during the crisis.15 Such a problem could occur in Canada if the chief public health officer is provided with the same independence as, for example, an officer of Parliament, such as the auditor general of Canada. Therefore, a necessary component to help protect against controlling the influence of an autonomous official would be the provision of a guaranteed protected budget.

Table 1

Conclusion

The listeriosis outbreak has raised questions about the expected role of the Public Health Agency of Canada and its independence. Although providing further autonomy to the agency and its lead officer does have some important drawbacks and may be unpalatable to the federal government, ultimately it is in the government's best interests to provide this protection. A public health agency that can prevent public health emergencies such as the Escherichia coli outbreak in Walkerton, Ontario, or the bovine spongiform encephalopathy crisis would improve the government's electoral prospects. Most importantly, it would enhance confidence in government decision-making and protect the health of the public.

Key points.

The response to the recent listeriosis outbreak raises questions about the autonomy and independence of the Public Health Agency of Canada and its chief public health officer.

To address these concerns, the Public Health Agency of Canada should be provided with a protected budget.

The chief public health officer should be provided with additional protection against dismissal without cause.

The chief public health officer should be provided with unambiguous authority to communicate directly with the legislature and the public on matters deemed to be of serious concern to the public's health.

Acknowledgments

Kumanan Wilson holds the Canada Research Chair in Public Health Policy.

Footnotes

Published at www.cmaj.ca on Sept. 17, 2008.

Contributors: Both authors contributed substantially to the writing of the article and approved the final version for publication.

Competing interests: Kumanan Wilson has received funding for research from the Public Health Agency of Canada. No competing interests declared by Jennifer Keelan.

Correspondence to: Dr. Kumanan Wilson, Ottawa Hospital — Civic Campus, Administrative Services Building, Rm. 1009, Box 684, 1053 Carling Ave., Ottawa ON K1Y 4E9; fax 613 761-5492; kwilson@ohri.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Public Health Agency of Canada. Listeria moncytogenes outbreak. Update September 12, 2008. Ottawa (ON): The Agency; 2008. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/alert-alerte/listeria/listeria_2008-eng.php (accessed 2008 Sept 15).

- 2.Health Canada. Learning from SARS: renewal of public health in Canada: a report of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health, October 2003. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2003. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/sars-sras/pdf/sars-e.pdf (accessed 2008 Sept 15).

- 3.Health Canada. Learning from SARS: renewal of public health in Canada: a report of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health, October 2003. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2003. p.89. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/sars-sras/pdf/sars-e.pdf (accessed 2008 Sept 15).

- 4.Public Health Agency of Canada Act, SC 2006, c5, 7(1).

- 5.Sibbald B. News @ a glance. CMAJ 2004;170:1658.

- 6.Attaran A, MacDonald N, Stanbrook MB, et al. Listeriosis is the least of it [editorial]. CMAJ DOI:10.1503/cmaj.081477. Epub 2008 Sept 16 ahead of print (available at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/rapidpdf/cmaj.081477).

- 7.Public Service Employment Act: special appointment regulations. Canada Gazette 2004;139:20.

- 8.Health Canada. Learning from SARS: renewal of public health in Canada: a report of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health, October 2003. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2003. p. 76. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/sars-sras/pdf/sars-e.pdf (accessed 2008 Sept 15).

- 9.Public Health Agency of Canada Act, SC 2006, c5, 7(2), 7(3).

- 10.Health Protection and Promotion Act, 2004, SO, c30, 1.2.

- 11.The Surgeon General's vital mission: challenges for the future [preliminary transcript]. Washington (DC): House of Representatives, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform; 2007 July 10. Available: http://oversight.house.gov/documents/20071127162330.pdf (accessed 2008 Sept 15).

- 12.Harris G. Surgeon general sees 4-year term as compromised. New York Times 2007 July 7. Available: www.nytimes.com/2007/07/11/washington/11surgeon.html (accessed 2008 Sept 15).

- 13.The Surgeon General Independence Act: to amend the Public Health Service Act to ensure the independence of the Surgeon General from political interference, HR 3447, 110th Congress, 1st Sess (2007).

- 14.Department of Health. The role of the chief medical officer of health. London (UK): The Department; 2007. Available: www.dh.gov.uk/en/Aboutus/MinistersandDepartmentLeaders/ChiefMedicalOfficer/AboutTheChiefMedicalOfficerCMO/DH_4103960 (accessed 2008 Sept 15).

- 15.Medical officer tells of BSE secrecy. BBC News 1998 Nov 6. Available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/background_briefings/bse/209006.stm (accessed 2008 Sept 15).