Abstract

Oseltamivir is a potent, well-tolerated antiviral for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza. Although no relationship with treatment could be demonstrated, recent reports of abnormal behavior in young individuals with influenza who were receiving oseltamivir have generated renewed interest in the central nervous system (CNS) tolerability of oseltamivir. This single-center, open-label study explored the pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate (OC) in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of healthy adult volunteers over a 24-hour interval to determine the CNS penetration of both these compounds. Four Japanese and four Caucasian males were enrolled in the study. Oseltamivir and OC concentrations in CSF were low (mean of observed maximum concentrations [Cmax], 2.4 ng/ml [oseltamivir] and 19.0 ng/ml [OC]) versus those in plasma (mean Cmax, 115 ng/ml [oseltamivir] and 544 ng/ml [OC]), with corresponding Cmax CSF/plasma ratios of 2.1% (oseltamivir) and 3.5% (OC). Overall exposure to oseltamivir and OC in CSF was also comparatively low versus that in plasma (mean area under the concentration-time curve CSF/plasma ratio, 2.4% [oseltamivir] and 2.9% [OC]). No gross differences in the pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir or OC were observed between the Japanese and Caucasian subjects. Oseltamivir was well tolerated. This demonstrates that the CNS penetration of oseltamivir and OC is low in Japanese and Caucasian adults. Emerging data support the idea that oseltamivir and OC have limited potential to induce or exacerbate CNS adverse events in individuals with influenza. A disease- rather than drug-related effect appears likely.

Oseltamivir is an orally administered anti-influenza agent of the neuraminidase inhibitor class. The ethyl ester prodrug oseltamivir is delivered orally as a phosphate salt and converted by hepatic esterases to the active metabolite oseltamivir carboxylate (OC) (10). OC specifically binds and inhibits the influenza virus neuraminidase enzyme that is essential for viral replication (21). In this way, oseltamivir limits the spread of influenza virus subtypes A and B within the infected host. When used as treatment, oseltamivir reduces the severity and duration of symptoms (22, 33), while prophylactic administration prevents their onset (9, 26).

In recent years, abnormal or delirious behaviors have been reported with a low incidence in young individuals with influenza who were also receiving oseltamivir (32). Cases arose most commonly in Japan but were also observed in Taiwan, Hong Kong, North America, Europe, and Australia. No causative association could be demonstrated, and similar events were also reported in the absence of oseltamivir (6, 12, 17, 24). Nevertheless, health and regulatory authorities in Japan and elsewhere have amended the product label to include precautions on the use of oseltamivir in young persons. These actions, and the associated media coverage, have fostered renewed interest in the central nervous system (CNS) tolerability of oseltamivir.

The currently available preclinical and clinical evidence suggests a low potential for oseltamivir to adversely affect CNS function, and no plausible mechanism for oseltamivir to cause CNS toxicity has been identified (32). However, only very limited data exist to describe the CNS penetration of oseltamivir and OC in humans. Equally little is known about the impact of ethnicity on the CNS profile of these entities. In this study, we investigated the pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir and OC in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—the latter being a recognized surrogate for CNS penetration (29)—in healthy adult volunteers after a single oral administration of oseltamivir phosphate. Although not powered to formally examine the impact of ethnicity on CNS penetration, we also considered whether any gross differences might exist by including both Caucasian and Japanese subjects in our study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and subjects.

This exploratory trial was a single-center, open-label, single-dose, pharmacokinetic study that was conducted in the United States between 16 July 2007 and 17 August 2007. The trial complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as amended in Tokyo, Venice, Hong Kong, and South Africa). The study protocol and materials were approved by an independent ethics committee, and written informed consent was provided by all participants. The study fully adhered to good clinical practice guidelines (ICH Tripartite Guideline, January 1997).

The study aimed to recruit eight healthy adult male and female volunteers: four of Japanese origin (born in Japan of Japanese parents and grandparents and living for <5 years outside Japan) and four of Caucasian origin (white Hispanic or non-Hispanic). The numbers of males and females were intended to be the same in both ethnic groups. Inclusion criteria were age of 20 to 45 years, body mass index of 18 to 30 kg/m2, and ability to give written informed consent and comply with the study restrictions. Female subjects were required to be surgically sterile or postmenopausal for ≥1 year or to use two methods of contraception (including one barrier method) from study commencement until 7 days postdosing. Exclusion criteria included clinically significant disease; allergy or immunodeficiency; history of raised intracerebral pressure or clinically significant vertebral joint pathology; major illness in the 30 days before screening or febrile illness in the 14 days prior to CSF sampling; pregnancy or lactation; relevant history of, or positive test for, drugs of abuse or alcohol; infection with hepatitis B or C virus or human immunodeficiency virus; or any other condition or disease rendering the subject unsuitable for the study. Prescription medication was not permitted to be taken within 7 days or six times its elimination half-life (t1/2) (whichever was longer) before study drug administration (excluding hormone replacement therapy and oral contraception). Occasional use of acetaminophen/paracetamol (up to 3 g/day) was allowed up to 24 h before dosing and as needed for treatment of side effects related to the CSF sampling procedure. Intravenous caffeine was also permitted for headache prophylaxis or treatment of side effects caused by the CSF sampling procedure.

All subjects underwent a screening period from day −28 to day −2, during which eligibility was assessed and written informed consent was provided. Screening involved a full medical history, a physical examination, an electrocardiogram (ECG), and a lumbar spine X-ray (unless the subject had such an X-ray taken within 1 year of screening). Samples for laboratory safety assessments (including serum biochemistry, hematology, urinalysis, and serology) and drug and alcohol abuse tests were taken after a 4-h fasting period. Female subjects were to undertake pregnancy tests.

Following successful screening, volunteers were admitted to the study unit on day −1 for a baseline safety assessment (recording of vital signs, ECG and laboratory safety assessments, and drug/alcohol abuse and pregnancy tests). On day 1, following an overnight fast, all subjects were catheterized in the lumbar region (for example, L3 to L4) for CSF sampling. This was performed using the dynabridging technique (California Clinical Trials Inc., California), in which the catheter is connected to a peristaltic pump for automatic timed withdrawal of CSF samples (approximately 6 ml per withdrawal). Subjects then received a single oral dose of 150 mg oseltamivir phosphate (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.), which corresponds to the recommended daily adult treatment dose of 75 mg twice daily. Venous blood samples (2 ml per withdrawal) were taken at the same time as CSF sampling was performed. Blood and CSF samples were taken immediately before dosing and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 20, and 24 h after dosing in the manner described above (14 sampling points in total). Subjects were discharged from the unit on day 4 and returned for a follow-up examination on days 10 to 12. Adverse events were recorded from screening until the end of follow-up.

Oseltamivir and OC assay.

Blood samples were drawn into EDTA blood collection tubes, and plasma was separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 1,500 × g and 4°C. CSF and plasma samples were stored at −70°C until analysis. Concentrations of oseltamivir and OC in plasma and CSF were measured using a specific and validated high-performance liquid chromatography method coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (Bioanalytical Systems Inc., Kenilworth, United Kingdom; SAP.055) based on a previously published method (35). The CSF samples were analyzed along with human EDTA plasma and human CSF control samples against calibration standards prepared in human EDTA plasma.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Concentration-versus-time profiles were generated, and the observed maximum concentration (Cmax) and time to observed maximum concentration (Tmax) were then determined for oseltamivir and OC in CSF and plasma. Standard noncompartmental methods were employed to characterize pharmacokinetic parameters using WinNonlin software (version 5.2; Pharsight Inc.). The following parameters were calculated where possible: area under the concentration-time curve from time zero to the last measurable concentration (AUC0-last) and infinity (AUC0-∞), apparent t1/2, and apparent oral clearance (CL/F). AUC values were computed using the linear-trapezoidal rule. AUC0-∞ was estimated using AUC0-last + Clast/λz, where Clast is the last measurable concentration and λz is the apparent elimination rate constant determined by log-linear regression of the last four terminal concentration data points fitting with an adjusted residual squared value of ≥0.90. The ratios of CSF/plasma exposure for Cmax and AUC0-last were also determined for each of the two analytes. In addition, oseltamivir/OC ratios (adjusted for the molecular weight differences) were calculated for Cmax and AUC0-last, once for the matrix plasma and separately for the matrix CSF.

RESULTS

A total of eight healthy male volunteers (four Caucasian and four Japanese) entered the study. No females were available for enrollment within the study timeframe (approximately 1 month). Demographic baseline characteristics were well balanced between the Caucasian and Japanese groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic baseline characteristics by ethnic group and total population

| Parameter | Mean (range)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian (n = 4) | Japanese (n = 4) | Total (n = 8) | |

| No. of subjects by gender | |||

| Male | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Age (yrs) | 29.0 (24-33) | 26.8 (24-35) | 27.9 (24-35) |

| Wt (kg) | 66.9 (61.2-73.5) | 65.6 (57.8-82.6) | 66.3 (57.8-82.6) |

| Ht (cm) | 173.3 (169-177) | 172.8 (169-176) | 173.0 (169-177) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.2 (20.7-23.5) | 22.1 (18.8-28.9) | 22.2 (18.8-28.9) |

Assay validation.

In both matrices, the calibration curve ranged from lower limits of quantification of 1 ng/ml and 10 ng/ml for oseltamivir and OC, respectively, up to 250 ng/ml for oseltamivir and 10,000 ng/ml for OC. For the analysis in plasma, the interassay precision (coefficient of variation) ranged from 3.8% to 5.4% for oseltamivir and from 2.2% to 9.1% for OC, and the accuracy ranged from 100.0% to 105.7% for oseltamivir and from 97.5% to 99.3% for OC. For the analysis in CSF, the interassay precision ranged from 0.9% to 3.3% for oseltamivir and from 1.6% to 9.1% for OC, and the accuracy ranged from 104.0% to 114.5% for oseltamivir and from 98.2% to 105.8% for OC. No marked inaccuracies were found in the concentration ranges of the plasma and CSF study samples.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

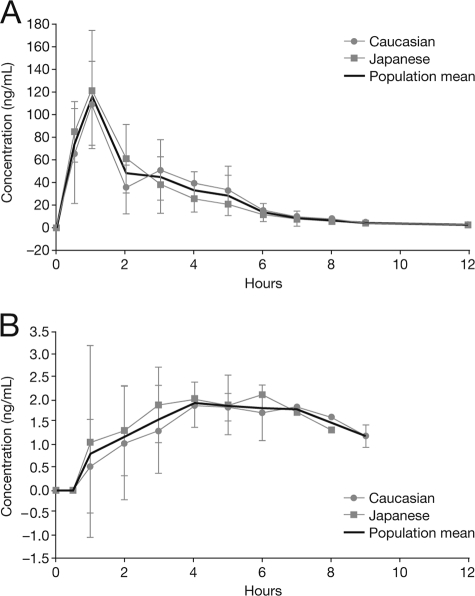

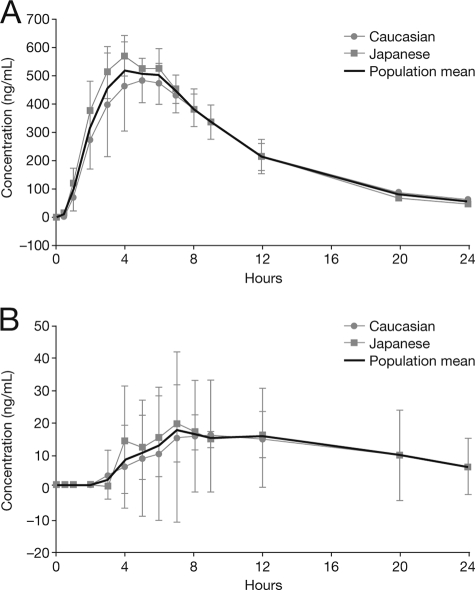

Figure 1 and Fig. 2 show the mean (± standard deviation [SD]) plasma and CSF concentration-time profiles for oseltamivir and OC in plasma and CSF for Japanese and Caucasian subjects and the overall population after a single oral dose of 150 mg oseltamivir phosphate. For both analytes, mean concentrations in CSF were considerably lower than those in plasma. Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the measured and computed pharmacokinetic parameters for oseltamivir and OC in plasma and CSF. Mean (± SD) Cmax plasma values were 115 (±40.0) ng/ml for oseltamivir and 544 (±92.6) ng/ml for OC. The corresponding median (range) Tmax values were 1.0 (0.5 to 4.0) h and 5.0 (4.0 to 6.0) h for oseltamivir and OC postdosing, respectively. In CSF, mean (± SD) Cmax values for oseltamivir and OC were 2.4 (±0.9) ng/ml and 19.0 (±14.9) ng/ml, respectively; these were measured at median (range) Tmax values of 3.5 (1.0 to 5.0) h and 8.0 (6.0 to 12.0) h postdosing.

FIG. 1.

(A) Mean (± SD) concentration-time profile for oseltamivir in plasma after a single oral dose of 150 mg oseltamivir phosphate in Caucasian (n = 4) and Japanese (n = 4) subjects and the overall population (n = 8). (B) Mean (± SD) concentration-time profile for oseltamivir in CSF after a single oral dose of 150 mg oseltamivir phosphate in Caucasian (n = 4) and Japanese (n = 4) subjects and the overall population (n = 8).

FIG. 2.

(A) Mean (± SD) concentration-time profile for OC in plasma after a single oral dose of 150 mg oseltamivir phosphate in Caucasian (n = 4) and Japanese (n = 4) subjects and the overall population (n = 8). (B) Mean (± SD) concentration-time profile for OC in CSF after a single oral dose of 150 mg oseltamivir phosphate in Caucasian (n = 4) and Japanese (n = 4) subjects and the overall population (n = 8).

TABLE 2.

Summary of the pharmacokinetic parameters of oseltamivir in plasma and CSF by ethnic group and total populationa

| Group (n) |

Cmax (ng/ml)

|

Tmax (h)

|

Clast (ng/ml)

|

Tlast (h)

|

AUC0-last (h·ng/ml)

|

t1/2 (h)

|

AUC0-∞ (h·ng/ml)

|

CL/F (liters/h)

|

CSF/plasma ratio (%)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Cmax | AUC0-last | |

| Caucasian (4) | 100 ± 39.6 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.0 (0.5-4.0) | 4.0 (2.0-5.0) | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 12.0 (9.0-12.0) | 7.5 (5.0-9.0) | 299 ± 62.8 | 9.4 ± 4.6 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | NCb | 304 ± 64.0 | NC | 512 ± 118 | NC | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 1.0 |

| Japanese (4) | 130 ± 39.8 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 1.0 (0.5-1.0) | 3.0 (1.0-5.0) | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 9.0 (9.0-12.0) | 4.0 (2.0-8.0) | 317 ± 92.3 | 5.9 ± 4.0 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | NC | 323 ± 93.6 | NC | 492 ± 126 | NC | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.8 |

| Total (8) | 115 ± 40.0 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 1.0 (0.5-4.0) | 3.5 (1.0-4.0) | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 10.5 (9.0-12.0) | 5.5 (2.0-9.0) | 308 ± 73.7 | 7.6 ± 4.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | NC | 313 ± 74.9 | NC | 502 ± 113 | NC | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 1.1 |

Values are arithmetic means (± SDs) apart from Tmax and Tlast, which are medians (range). Values are reported with three significant figures and/or a maximum of one decimal place.

NC, not calculated.

TABLE 3.

Summary of the pharmacokinetic parameters of OC in plasma and CSF by ethnic group and total populationa

| Group (n) |

Cmax (ng/ml)

|

Tmax (h)

|

Clast (ng/ml)

|

Tlast (h)

|

AUC0-last (h·ng/ml)

|

t1/2 (h)

|

AUC0-∞ (h·ng/ml)

|

CSF/plasma ratio (%)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Plasma | CSF | Cmax | AUC0-last | |

| Caucasianb (4) | 507 ± 117 | 17.7 ± 19.7 | 5.5 (4.0-6.0) | 8.0 (7.0-12.0) | 56.4 ± 9.8 | 12.0 ± 1.3 | 24.0 (24.0-24.0) | 12.0 (12.0-24.0) | 5,380 ± 1,180 | 185 ± 297 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | NCc | 5,860 ± 1,210 | NC | 3.5 ± 4.2 | 3.6 ± 6.0 |

| Japanese (4) | 581 ± 50.5 | 20.4 ± 11.3 | 4.5 (4.0-6.0) | 7.5 (6.0-12.0) | 44.0 ± 19.4 | 16.3 ± 7.3 | 24.0 (24.0-24.0) | 12.0 (12.0-12.0) | 5,700 ± 826 | 129 ± 67.6 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | NC | 6,030 ± 1,000 | NC | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 2.3 ± 1.1 |

| Total (8) | 544 ± 92.6 | 19.0 ± 14.9 | 5.0 (4.0-6.0) | 8.0 (6.0-12.0) | 50.2 ± 15.7 | 14.5 ± 5.7 | 24.0 (24.0-24.0) | 12.0 (12.0-24.0) | 5,540 ± 957 | 157 ± 202 | 5.4 ± 0.8 | NC | 5,950 ± 1,030 | NC | 3.5 ± 2.9 | 2.9 ± 4.1 |

Values are arithmetic means(± SDs) apart from Tmax and Tlast, which are medians (ranges). Values are reported with three significant figures and/or a maximum of one decimal place.

For one Caucasian subject, all CSF metabolite concentrations were below quantifiable limits and were interpreted as 0 ng/ml; pharmacokinetic parameters for OC in CSF were not calculated, but Cmax and AUC0-last values of 0 were included in the respective summary statistics for these parameters and were used to calculate the respective CSF/plasma ratios of 0.

NC, not calculated.

Oseltamivir concentrations were quantifiable for up to 12 h postdosing in plasma and 9 h in CSF. OC concentrations were detected for up to 24 h in plasma and for up to 12 h in CSF in all but one Caucasian subject. This subject displayed the highest CSF concentrations for OC with a Cmax value of 45.9 ng/ml at 7 h postdosing, but the oseltamivir concentrations in CSF were not remarkably high compared to those for the remaining subjects. This subject was also shown to have blood contamination of the CSF up to 5 h postdosing, and OC persisted in the subject's CSF samples until 24 h after drug administration. In a different Caucasian subject, OC concentrations were not detected in CSF at any time point, while oseltamivir concentrations were measurable until 6 h postdosing. In this subject, values for OC in CSF of zero were assigned for Cmax, AUC0-last, and the respective CSF/plasma ratios, and these values were included in the respective summary statistics. The intersubject pharmacokinetic variabilities (SDs) for the parameters Cmax and AUC0-last in plasma in relation to the sample mean (percent coefficient of variation) were approximately 34% and 17% for oseltamivir and OC, respectively. This is consistent with previous experience with the drug (Roche data on file). The corresponding intersubject variabilities for Cmax and AUC0-last in CSF were higher for oseltamivir (36% for Cmax and 48% for AUC0-last) and OC (78% for Cmax and 129% for AUC0-last), the latter two percentages reflecting the most extreme Cmax values measured for OC (0 ng/ml and 45.9 ng/ml).

In the overall population, the mean (± SD) Cmax CSF/plasma ratios (in %) for oseltamivir and OC were 2.1% (±0.5%) and 3.5% (±2.9%), respectively (Tables 2 and 3). For both oseltamivir and OC, the concentration-versus-time profiles in plasma were sufficient to estimate AUC0-∞ and t1/2 and to derive the apparent oral plasma clearance for oseltamivir. For both analytes, plasma AUC0-last covered more than 90% of plasma AUC0-∞. The mean plasma t1/2 of OC was triple that of oseltamivir (5.4 h versus 1.8 h), and the mean plasma CL/F for oseltamivir was 502 liters/h. In contrast to the pharmacokinetic plasma data, the CSF concentration-versus-time profiles did not allow a reliable assessment of AUC0-∞ for either analyte; hence, only AUC0-last values are reported for CSF. The mean (± SD) AUC0-last CSF/plasma ratios for the total population for oseltamivir and OC were 2.4% (±1.1%) and 2.9% (±4.1%), respectively. The individual AUC0-last values in CSF covered a time period between 2 and 9 h for oseltamivir and 12 or 24 h for OC and the individual AUC0-last values in plasma covered between 9 and 12 h for oseltamivir and 12 and 24 h for OC. If approximate free plasma concentrations (58% for oseltamivir and 95% for OC [Roche data on file]) were used to calculate the respective CSF/plasma ratios, these figures would double for oseltamivir (that is, to approximately 5%) but would remain similar for OC. In the subject with blood-contaminated CSF, in whom higher OC CSF concentrations were observed, the resulting CSF/plasma ratios based on total concentrations for OC were 9.5% (Cmax) and 11.7% (AUC) (these values would be only slightly higher if free concentrations were considered). In the overall population, the mean (± SD) Cmax oseltamivir (prodrug)/OC (active metabolite) ratios (adjusted for the molecular weight differences) were 18.8% (±4.1%) and 12.4% (±5.1%) in plasma and CSF, respectively. The AUC0-last oseltamivir/OC molar ratios were 5.1% (±0.9%) and 9.4% (±8.8%) in plasma and CSF, respectively.

This study was not empowered to identify differences between ethnic groups. Nevertheless, no gross differences for any pharmacokinetic parameters were observed for either oseltamivir or OC between the Caucasian and Japanese subjects (Fig. 1 and 2).

Safety.

A total of 20 adverse events were reported during the study, all of which were mild to moderate in intensity and resolved without sequelae (Table 4). All but two events were unrelated to the study medication: one chest pain with a remote relationship to oseltamivir and one headache with a possible relationship to oseltamivir. In general, headache, back pain, and post-lumbar-puncture syndrome occurred due to the lumbar puncture procedure. Caffeine and paracetamol were administered to treat these conditions. No deaths, serious adverse events, or withdrawals after drug administration occurred during the study, and there were no clinically relevant changes in vital signs, ECG, or laboratory parameters at follow-up.

TABLE 4.

Subjects reporting adverse events by ethnic group and total population

| Ethnic group (n) | All body system disorders

|

No. of subjects with:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects with ≥1 AEa | Total no. of AEs | Nervous system disorders

|

Gastrointestinal disorders

|

Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders

|

Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications

|

Eye disorders

|

|||

| Headache | Nausea | Vomiting | Back pain | Musculoskeletal stiffness | Post-lumbar-puncture syndrome | Photophobia | |||

| Caucasian (4) | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Japanese (4) | 4 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Total (8) | 6 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

AE, adverse event.

DISCUSSION

In the current exploratory study, we evaluated the pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir and OC in the CSF and plasma of healthy Japanese and Caucasian adult volunteers to further our understanding of the CNS penetration of these entities. Concentrations of oseltamivir and OC in CSF were low (mean Cmax, 2.4 ng/ml for oseltamivir and 19.0 ng/ml for OC in CSF), and maximum concentrations were 2.1% and 3.5% of those attained in plasma, respectively (mean Cmax, 115 ng/ml for oseltamivir and 544 ng/ml for OC in plasma). Overall exposure was also low in CSF compared with plasma (mean AUC CSF/plasma ratios of 2.4% for oseltamivir and 2.9% for OC). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the CNS penetration of oseltamivir and OC is low in healthy individuals. The relative Cmax and AUC0-last oseltamivir/OC ratios in plasma reported in this study are consistent with data from previous studies with healthy volunteers (Roche data on file).

These findings are consistent with two case reports describing CNS penetration in influenza virus-infected individuals (5, 31). These cases comprise examination of the CSF of a 10-year-old male with influenza B virus-associated encephalitis (31) and a postmortem examination of several brain regions from a 13-year-old Japanese male with influenza who had taken a single dose of oseltamivir and subsequently fell to his death from a building (5). In both of these cases, no or low concentrations of oseltamivir or OC were detected in CSF or human brain homogenates (5, 31). Preclinical studies involving rats and ferrets also show uniformly low brain penetration following administration of oseltamivir phosphate (Roche data on file). For oseltamivir, brain exposure in rats after intravenous administration was approximately 20% of plasma values, whereas for OC it was approximately 3%. It should also be noted that these studies employed whole-brain homogenates and that concentrations in tissue may have been overestimated due to confounding by blood vessel content, especially in cases with high plasma-to-brain ratios (Roche data on file). Recent studies in mice showed that access to the CNS by oseltamivir was also restricted by P-glycoprotein (P-gp); it should be noted that in the absence of P-gp in knockout mice, the brain/plasma ratio was still low (around 0.35) (20, 25). The limited access of OC to brain is thought to be due to its low lipophilicity leading to low passive diffusion across the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

It is recognized that, due to the short time period in which quantifiable concentrations in CSF could be measured, there was a potential for underestimation of CSF AUC0-last values. This could also have led to underestimation of the calculated AUC0-last CSF/plasma ratios. However, it is reassuring that even when a “worst-case scenario” was applied, with the last measurable CSF concentration for each subject extrapolated to the plasma time to last measurable concentration (Tlast), the AUC0-last values in CSF for the total population for oseltamivir and OC were 14.0 (±3.6) h·ng/ml and 291 (±204) h·ng/ml, respectively. The values remained of the same magnitude as those of the AUC0-last values estimated using the actual CSF Tlast values, which were 7.6 (±4.4) h·ng/ml for oseltamivir and 151 (±202) h·ng/ml for OC. The corresponding mean (± SD) AUC0-last (CSF)/AUC0-last (plasma) ratios for the total population were still very low when this conservative approach was employed: 4.6% (±1.0%) for oseltamivir and 5.2% (±3.9%) for OC.

No females were available for enrollment within the restraints imposed by the study timelines. This was not expected to affect the outcome of the study, as previous investigations within the wider oseltamivir clinical program have indicated no significant gender differences in the pharmacokinetics of either oseltamivir or OC (Roche data on file).

In the overall study population, oseltamivir was detectable in the CSF for a median duration of 5.5 h and in OC for a median duration of 12.0 h. In one subject, whose first six CSF samples were contaminated with blood, OC persisted in the CSF for 24.0 h. While oseltamivir is a P-gp substrate and is eliminated from the CNS by this transporter, it has been speculated that active efflux of OC from the brain at the BBB may occur via organic anion transporter 3 (OAT3) (25), which is a homologue of OAT1, the mediator of renal tubular secretion of OC (11). OAT3 is expressed at the BBB and actively eliminates organic anions from the brain (15, 16).

Within the limitations of the study design (i.e., exploratory nature and limited sample size), no gross differences in the CSF or plasma pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir or OC were observed between the Caucasian and Japanese subjects. This is consistent with published findings showing no discernible differences in the overall pharmacokinetic profiles of oseltamivir in plasma between Japanese and Caucasian adults (28) and children (7). It has been suggested that genetic variations may contribute to the higher incidence of CNS events reported in certain ethnic groups. For example, Shi et al. postulated that variations in the human carboxylesterases hCES1 and hCES2 could lead to decreased conversion and therefore higher-than-expected systemic concentrations of oseltamivir (30). Utilizing a population pharmacokinetic model, simulations of oseltamivir 75-mg twice-daily dosing without oseltamivir conversion to OC gave steady-state Cmax values that were around 14-fold higher than those achieved when the metabolic pathway was intact (Roche data on file). Nevertheless, these estimated values were approximately 1.4-fold lower than those observed in a clinical trial of six subjects who received 1,000-mg doses, in which no neuropsychiatric adverse events of note were seen (Roche data on file). Genetic variants of OAT1 (which mediates renal secretion of OC) (1, 4, 19) and P-gp (which controls BBB penetration of oseltamivir) (13, 27) do occur, but alterations to their function as a result have not been demonstrated.

Given the low CSF concentrations observed in subjects in the current study, the potential for oseltamivir and OC to induce or exacerbate CNS dysfunction appears low. Ose et al. have suggested that OC could act on human neuraminidase enzymes (sialidases) in the brain and disrupt the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in neuronal cell death (25). However, in vitro data suggest that neither oseltamivir nor OC inhibits any of the four human neuraminidases at concentrations of up to 1 mM (32). Furthermore, investigation of 155 different molecular drug targets, covering a broad range of receptors, enzymes, and ion channels, many of which are relevant to the CNS, did not produce any relevant findings, indicating a lack of mechanism for neuropsychiatric adverse events with oseltamivir or OC (18). Clinical data also support the lack of an association between oseltamivir and CNS adverse events in young individuals with influenza. In two Japanese case series, the onset of abnormal or delirious behavior was found to occur both before and after the initiation of oseltamivir therapy (8, 23), suggesting no temporal association between the two events. Epidemiological studies also demonstrate that the incidence of neuropsychiatric adverse events is similar between patients with influenza who receive oseltamivir and those who receive no antiviral (2, 34).

Oseltamivir was well tolerated in this study, with the majority of adverse events related to the continuous indwelling lumbar catheterization lumbar puncture technique used to obtain CSF samples. Methods involving continuous collection of CSF for 12 to 36 h, with up to two sampling periods separated by a 7- to 14-day recovery period, are used in experimental medicine and proof-of-principle studies. They can establish pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic models (hence “dynabridging”) and downstream (proteomic) effects of drug administration. Continuous indwelling lumbar catheterization has been performed in over 450 healthy volunteers and patients at California Clinical Trials, from 1997 to the present (3). There have been no serious adverse events from these procedures, and the rate of adverse events has been no different from that for single lumbar punctures (14).

This study supports the idea that the CNS penetration of oseltamivir and OC is low in healthy Japanese and Caucasian individuals. Preclinical and clinical data support the idea that oseltamivir and OC have a limited potential to induce or exacerbate CNS adverse events in individuals with influenza. A disease- rather than drug-related effect appears likely.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript was prepared with the assistance of Stephen Purver and colleagues at Gardiner Caldwell Communications Ltd., Macclesfield, United Kingdom. Special thanks go to all study team members at F. Hoffmann-La Roche, especially the bioanalytical monitor, Caroline Kreuzer, for their assistance with this study.

Financial support for the preparation of the paper was provided by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., the manufacturer of oseltamivir. M.S., B.K., L.B., A.P., G.H., E.P.P., and C.R.R. are current employees of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 August 2008.

Roche clinical trial number BP21288.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bleasby, K., L. A. Hall, J. L. Perry, H. W. Mohrenweiser, and J. B. Pritchard. 2005. Functional consequences of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the human organic anion transporter hOAT1 (SLC22A6). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314:923-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumentals, W. A., and X. Song. 2007. The safety of oseltamivir in patients with influenza: analysis of healthcare claims data from six influenza seasons. Med. Gen. Med. 9:23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ereshefsky, L., S. S. Jhee, M. T. Leibowitz, S. Moran, M. Yen, and L. Gertsik. 2006. Demonstrating proof of principle and finding the right dose: the role of CSF ‘Dynabridging’ studies. Abstr. 25th Bienn. Congr. Coll. Int. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. (CINP), Chicago, IL.

- 4.Fujita, T., C. Brown, E. J. Carlson, T. Taylor, M. de la Cruz, S. J. Johns, D. Stryke, M. Kawamoto, K. Fujita, R. Castro, C. W. Chen, E. T. Lin, C. M. Brett, E. G. Burchard, T. E. Ferrin, C. C. Huang, M. K. Leabman, and K. M. Giacomini. 2005. Functional analysis of polymorphisms in the organic anion transporter, SLC22A6 (OAT1). Pharmacogenet. Genomics 15:201-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuke, C., Y. Ihama, and T. Miyazaki. 2008. Analysis of oseltamivir active metabolite, oseltamivir carboxylate, in biological materials by HPLC-UV in a case of death following ingestion of Tamiflu. J. Leg. Med. (Tokyo) 10:83-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukumoto, Y., A. Okumura, F. Hayakawa, M. Suzuki, T. Kato, K. Watanabe, and T. Morishima. 2007. Serum levels of cytokines and EEG findings in children with influenza associated with mild neurological complications. Brain Dev. 29:425-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gieschke, R., R. Dutkowski, J. Smith, and C. R. Rayner. 2007. Similarity in the pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate in Japanese and Caucasian children. Abstr. Options Control Influenza VI, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, abstr. P921.

- 8.Goshima, N., T. Nakano, M. Nagao, and T. Ihara. 2006. Clinical study of abnormal behavior during influenza. Infect. Immun. Childhood 18:376. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayden, F. G., R. Belshe, C. Villanueva, R. Lanno, C. Hughes, I. Small, R. Dutkowski, P. Ward, and J. Carr. 2004. Management of influenza in households: a prospective, randomized comparison of oseltamivir treatment with or without postexposure prophylaxis. J. Infect. Dis. 189:440-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, G., J. Massarella, and P. Ward. 1999. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the prodrug oseltamivir and its active metabolite Ro 64-0802. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 37:471-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill, G., T. Cihlar, C. Oo, E. S. Ho, K. Prior, H. Wiltshire, J. Barrett, B. Liu, and P. Ward. 2002. The anti-influenza drug oseltamivir exhibits low potential to induce pharmacokinetic drug interactions via renal secretion-correlation of in vivo and in vitro studies. Drug Metab. Dispos. 30:13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, Y. C., T. Y. Lin, S. L. Wu, and K. C. Tsao. 2003. Influenza A-associated central nervous system dysfunction in children presenting as transient visual hallucination. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22:366-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishikawa, T., H. Hirano, Y. Onishi, A. Sakurai, and S. Tarui. 2004. Functional evaluation of ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein) polymorphisms: high-speed screening and structure-activity relationship analyses. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 19:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhee, S. S., and V. Zarotsky. 2003. Safety and tolerability of serial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collections during pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies: 5 years' experience. Clin. Res. Regul. Aff. 20:357-363. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi, R., H. Kusuhara, T. Abe, H. Endou, and Y. Sugiyama. 2004. Involvement of multiple transporters in the efflux of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors across the blood-brain barrier. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 311:1147-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kikuchi, R., H. Kusuhara, D. Sugiyama, and Y. Sugiyama. 2003. Contribution of organic anion transporter 3 (Slc22a8) to the elimination of p-aminohippuric acid and benzylpenicillin across the blood-brain barrier. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306:51-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin, C. H., Y. C. Huang, C. H. Chiu, C. G. Huang, K. C. Tsao, and T. Y. Lin. 2006. Neurologic manifestations in children with influenza B virus infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25:1081-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindemann, L., H. Jacobsen, C. Schweitzer, C. Schuhbauer, D. Reinhardt, C. Fischer, C. Diener, S. Gatti, J. Beck, J. G. Wettstein, H. Loetscher, E. Prinssen, and M. Brockhaus. 2008. Comprehensive in vitro pharmacological selectivity profile of oseltamivir prodrug (Tamiflu) and oseltamivir active metabolite. Abstr. Exp. Biol., San Diego, CA, abstr. LB671.

- 19.Marzolini, C., R. G. Tirona, and R. B. Kim. 2004. Pharmacogenomics of the OATP and OAT families. Pharmacogenomics J. 5:273-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morimoto, K., M. Nakakariya, Y. Shirasaka, C. Kakinuma, T. Fujita, I. Tamai, and T. Ogihara. 2008. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) efflux transport at the blood-brain barrier via P-glycoprotein. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36:6-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moscona, A. 2005. Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:1363-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson, K. G., F. Y. Aoki, A. D. Osterhaus, S. Trottier, O. Carewicz, C. H. Mercier, A. Rode, N. Kinnersley, P. Ward, et al. 2000. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in treatment of acute influenza: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 355:1845-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okumura, A., T. Kubota, T. Kato, and T. Morishima. 2006. Oseltamivir and delirious behavior in children with influenza. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25:572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okumura, A., T. Nakano, Y. Fukumoto, K. Higuchi, H. Kamiya, K. Watanabe, and T. Morishima. 2005. Delirious behavior in children with influenza: its clinical features and EEG findings. Brain Dev. 27:271-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ose, A., H. Kusuhara, K. Yamatsugu, M. Kanai, M. Shibasaki, T. Fujita, A. Yamamoto, and Y. Sugiyama. 2008. P-glycoprotein restricts the penetration of oseltamivir across the blood-brain barrier. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36:427-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters, P. H., Jr., S. Gravenstein, P. Norwood, V. De Bock, A. Van Couter, M. Gibbens, T. A. von Planta, and P. Ward. 2001. Long-term use of oseltamivir for the prophylaxis of influenza in a vaccinated frail older population. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 49:1025-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakurai, A., A. Tamura, Y. Onishi, and T. Ishikawa. 2005. Genetic polymorphisms of ATP-binding cassette transporters ABCB1 and ABCG2: therapeutic implications. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 6:2455-2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schentag, J., G. Hill, T. Chu, and C. Rayner. 24 April 2007. Similarity in pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate in Japanese and Caucasian subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 47:689-696. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen, D. D., A. A. Artru, and K. K. Adkison. 2004. Principles and applicability of CSF sampling for the assessment of CNS drug delivery and pharmacodynamics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 56:1825-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi, D., J. Yang, D. Yang, E. L. Lecluyse, C. Black, L. You, F. Akhlaghi, and B. Yan. 2006. Anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir is activated by carboxylesterase HCE1, and the activation is inhibited by antiplatelet agent clopidogrel. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 319:1477-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Straumanis, J. P., M. D. Tapia, and J. C. King. 2002. Influenza B infection associated with encephalitis: treatment with oseltamivir. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 21:173-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toovey, S., C. R. Rayner, E. Prinssen, T. Chu, B. Donner, R. Dutkowski, S. Sacks, J. Solsky, I. Small, and D. Reddy. 2008. Post-marketing safety assessment of neuropsychiatric adverse event risk in patients with influenza treated with oseltamivir. Abstr. X Int. Symp. Respir. Viral Infect., Singapore City, Singapore.

- 33.Whitley, R. J., F. G. Hayden, K. S. Reisinger, N. Young, R. Dutkowski, D. Ipe, R. G. Mills, and P. Ward. 2001. Oral oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:127-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcox, M., and S. Zhu. 2007. Oseltamivir therapy appears not to affect the incidence of neuropsychiatric adverse events in influenza patients. Abstr. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Chicago, IL, abstr. V-1223a.

- 35.Wiltshire, H., B. Wiltshire, A. Citron, T. Clarke, C. Serpe, D. Gray, and W. Herron. 2000. Development of a high-performance liquid chromatographic-mass spectrometric assay for the specific and sensitive quantification of Ro 64-0802, an anti-influenza drug, and its pro-drug, oseltamivir, in human and animal plasma and urine. J. Chromatogr. B 745:373-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]