Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344, in which efflux pump genes (acrB, acrD, acrF, tolC) or regulatory genes thereof (marA, soxS, ramA) were inactivated, was grown in the presence of 240 antimicrobial and nonantimicrobial agents in the Biolog Phenotype MicroArray. Mutants lacking tolC, acrB, and ramA grew significantly worse than other mutants in the presence of 48 agents (some of which have not previously been identified as substrates of AcrAB-TolC) and particularly poorly in the presence of phenothiazines, which are human antipsychotics. MIC testing revealed that the phenothiazine chlorpromazine had antimicrobial activity and synergized with common antibiotics against different Salmonella serovars and SL1344. Chlorpromazine increased the intracellular accumulation of ethidium bromide, which was ablated in mutants lacking acrB, suggesting an interaction with AcrB. High-level but not low-level overexpression of ramA increased the expression of acrB; conferred resistance to chloramphenicol, tetracycline, nalidixic acid, and triclosan and organic solvent tolerance; and increased the amount of ethidium bromide accumulated. Chlorpromazine induced the modest overproduction of ramA but repressed acrB. These data suggest that phenothiazines are not efflux pump inhibitors but influence gene expression, including that of acrB, which confers the synergy with antimicrobials observed.

In Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, resistance-nodulation-division (RND) efflux pumps such as AcrAB-TolC demonstrate a broad substrate range, including antimicrobials, dyes, and detergents (5, 14, 22, 23, 33). Efflux pumps also confer resistance to biliary salts in E. coli and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium in vitro (18, 20, 29), suggesting that a physiological function of active efflux is the export of intracellular solutes and protection against a variety of substances in this environment. Several studies have shown that efflux pumps are involved in the survival of bacteria within their ecological niches, as mutants lacking components of efflux pumps are attenuated within their host (9, 10, 24, 27). The deletion or inactivation of acrB in E. coli and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium confers hypersusceptibility to tetracycline, fusidic acid, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, novobiocin, bile salts, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, crystal violet, acridine orange, and ethidium bromide (14, 20, 24, 28). In the presence of AcrAB, the role of other efflux pumps in conferring antimicrobial resistance in both species seems to be minor, with the deletion of acrD and acrF resulting in hypersusceptibility only to ampicillin and ethidium bromide (14, 24, 28). Lee et al. (19) reported that combinations of different efflux pump superfamilies contribute additively to antimicrobial resistance, decreasing susceptibility to a greater extent than a single superfamily of pumps. A lack of tolC in both E. coli and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium also confers hypersusceptibility to a wide range of compounds, including chloramphenicol, fusidic acid, erythromycin, novobiocin, SDS, acridine orange, and ethidium bromide, and increases in susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, tetracycline, nalidixic acid, and bile salts (10, 13, 24, 28). While the AcrAB-TolC efflux system is considered the major efflux pump complex in both E. coli and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, the larger range of substrates to which hypersusceptibility is conferred in ΔtolC mutants compared to the range of substrates to which hypersusceptibility is conferred in ΔacrB mutants is due to the promiscuous nature of TolC, which, by associating with other efflux pump proteins, effluxes substrates independently of AcrB. It has also been demonstrated in E. coli that a functional AcrAB-TolC complex is required for plasmid-mediated tetracycline resistance, even though tetA is the major resistance determinant (13), and in Salmonella, it has been demonstrated that functional forms of acrB and tolC are required for florfenicol resistance (8).

ramA, a member of the AraC-XylS family of transcriptional regulators, is found in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, Enterobacter cloacae, and Klebsiella pneumoniae but not E. coli (16, 17, 26, 30). The expression of ramA from Salmonella serovar Paratyphi or Typhimurium in E. coli conferred decreased susceptibility to nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline (31, 36). However, inactivation of ramA in wild-type Salmonella serovar Typhimurium did not confer a concurrent increase in antibiotic susceptibility, and inactivation in clinical isolates with multidrug resistance (MDR) conferred only a modest decrease in MICs (25, 30). Additionally, whereas spontaneous mutants selected from marA::aph or soxS::aph strains after exposure to ciprofloxacin can be either MDR or resistant to quinolones alone, those selected from ramA::aph strains were resistant only to quinolones (25). Recently, it has been shown that ramR, a tetR-like repressor, represses ramA, and when ramR is inactivated, ramA overexpression is observed and MDR is conferred (1).

In this study, we demonstrate that the Phenotype MicroArray (PM) system can be used to identify compounds in which growth is better or worse when genes that encode components of RND efflux pumps or genes that regulate their expression are inactivated. Chlorpromazine and similar compounds with activities against Salmonella serovar Typhimurium were identified. Further experiments suggested that chlorpromazine is an inducer of ramA and represses the expression of acrB. We also demonstrate that in isogenic strains, the overexpression of ramA confers MDR and organic solvent tolerance through the overexpression of acrB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media used.

All mutants were derived from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 (34), as described previously (12, 14), and various efflux pump genes and genes that regulate their expression were inactivated (Table 1). In strains L561 (ΔacrF) and L644 (ΔacrB), the aph gene used to disrupt the target gene had been removed by using the pCP20 helper plasmid (12). The gene disruptions were transduced into SL1344 by using P22 to minimize the risk of bacteriophage λ red recombinase-mediated mutations. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth was used throughout with no alterations other than changes to the sodium chloride concentrations where indicated. Specialized medium (Biolog, Inc.) was used when growth investigations were performed with the PM system. To overexpress ramA, pTRChisA::ramA (31) was transformed into L133 (ramA::aph). The level of overexpression was determined by reverse transcription-PCR, as described previously (14), with 20-mer primer sequences (Invitrogen, United Kingdom) internal to Salmonella serovar Typhimurium ramA (forward primer 5′-TCCGCTCAGGTTATCGACAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGCTTCCGTTCACGCACGTA-3′) and acrB (forward primer 5′-CGTGTTATGACGGAAGAAGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCCATACCGACGACGATAAT-3′). The growth of the mutants was assayed by inoculating 4% of an overnight culture of the relevant strain into 180 μl fresh LB broth in a 96-well microtiter tray. The trays were subsequently incubated at 37°C in a Fluostar Optima spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech, United Kingdom) with regular shaking, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was recorded every 45 s. The data presented are from at least three independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Genotype | Strain or plasmid | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium | 14028S | ATCC 14028 |

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium | LT2 | ATCC 19585 |

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium | SL1344 | 36 |

| SL1344 ΔacrB | L101 | 3 |

| SL1344 acrD::aph | L103 | 10 |

| SL1344 ΔacrF | L106 | 3 |

| SL1344 tolC::aph | L107 | 10 |

| SL1344 marA::aph | L108 | 28 |

| SL1344 soxS::aph | L561 | 28 |

| SL1344 ramA::aph | L644 | 28 |

| SL1344 transduced acrB::aph | L130 | 10 |

| SL1344 transduced acrD::aph | L131 | 10 |

| SL1344 transduced acrF::aph | L132 | 10 |

| SL1344 transduced tolC::aph | L133 | 10 |

| SL1344 transduced marA::aph | L135 | 10 |

| SL1344 transduced soxS::aph | L109 | 10 |

| SL1344 transduced ramA::aph | L110 | 10 |

| L133-pTRChisA::ramA | L786 | This study |

| Salmonella serovar Binza | 8269 | HPAa |

| Salmonella serovar Enteritidis | 5188 | HPA |

| Salmonella serovar Haifa | 9878 | HPA |

| Salmonella serovar Heidelberg | 5171 | HPA |

| Salmonella serovar Mbandaka | 7892 | HPA |

| Salmonella serovar Montevideo | 5747 | HPA |

| Salmonella serovar Newport | 129 | HPA |

| Salmonella serovar Virchow | 5742 | HPA |

| IPTG-inducible ramA overexpression | pTRChisA::ramA | 32 |

| IPTG-inducible ramA overexpression | pTRChisA | Invitrogen, United Kingdom |

HPA, Health Protection Agency, Colindale, United Kingdom.

PM system.

All tests with the PM system were performed as described previously (37). All fluids, agar media, and arrays are commercially available from Biolog. Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344 and the mutants were grown overnight at 37°C on specialized Biolog agar. Colonies were harvested from the surface of an agar plate with a sterile cotton wool swab and suspended in 15 ml of Inoculating Fluid-10 until the cell density equaled 42% transmittance (T) on a Biolog turbidimeter and was then diluted further to give a density of 85% T (an A420 of approximately 0.12). A total of 600 μl of the 85% T suspension was diluted 200-fold into 120 ml of Inoculating Fluid-10; and 100 μl per well was used to inoculate plates PM11A to PM20, which measure sensitivity to a wide variety of antibiotics, antimetabolites, and other growth inhibitors. No growth supplements were added to any of the inoculating fluids. All PM plates were incubated at 37°C in an OmniLog plate reader and were monitored for color changes in the wells. Readings were recorded for 36 h for all PM plates. Kinetic data were analyzed with OmniLog PM software (Biolog). On the basis of the work of Zhou et al. (37), a testwide median value of growth of approximately ±10,000 the area under the curve was used, and substrates showing a ±1.5-fold (±≥15,000 area under curve, arbitrary units) difference in the results between strain SL1344 and the mutant being tested were considered significantly different. For analysis, on the basis of their average growth over the entire array, the strains were divided into two groups, one consisting of marA::aph, ramA::aph, acrD::aph, and ΔacrF strains and the other consisting of tolC::aph and ΔacrB strains. The average growth value for each strain and concentration were taken, and individual values were plotted against the average value for the group. A trend line was applied for each strain, and clusters with outlying individual growth values were examined further. This process was termed “cluster analysis.”

Quantification of gene expression.

Gene expression analysis was conducted by comparative reverse transcription-PCR and denaturing high-pressure liquid chromatography, as described previously (6, 14).

Susceptibility to antibiotics and phenothiazines.

The MICs of phenothiazines for the mutants were determined by the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy standardized broth microdilution method (4). The lowest concentration of antimicrobial that caused no visible growth was determined to be the MIC of that compound. The compounds tested were amitriptyline, thioridazine, trifluoperazine, orphenadrine, and chlorpromazine (Sigma-Aldrich, United Kingdom). MICs were determined independently three times. Furthermore, the MICs of nalidixic acid, norfloxacin, tetracycline, ethidium bromide, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, acridine orange, SDS, bile salts, sodium deoxycholate, rhodamine 6G, and crystal violet (all from Sigma-Aldrich, United Kingdom) and triclosan (Ciba, Switzerland) were determined in the presence of chlorpromazine, thioridazine, amitriptyline, and trifluoperazine (at concentrations of 100 μg/ml and 200 μg/ml) to examine whether the phenothiazines had synergistic and/or additive effects on the activities of these agents. When the MICs for L786 (ramA::aph-pTRChisA::ramA) were determined, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 50 μg/ml ampicillin were added to the growth medium.

Accumulation and efflux of ethidium bromide with or without phenothiazines.

The accumulation of ethidium bromide was determined as described previously (21). Cultures were grown at 37°C until an OD600 of 0.7 was obtained. In the case of ramA::aph-pTRChisA::ramA, IPTG was added to 1 mM at an OD600 of ∼0.6, and then the culture was reincubated for 30 min until the OD600 reached 0.7 ± 0.02. The cells were centrifuged, washed with potassium phosphate buffer to remove all traces of external ethidium bromide, recentrifuged, and then resuspended in potassium phosphate buffer to an OD660 of 0.2. The cells were incubated in a sterile tube with stirring at 37°C for 10 min to equilibrate. The cultures were then spilt into two aliquots, ethidium bromide was added to both aliquots at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml, and chlorpromazine was added to one aliquot at a final concentration of 100 or 200 μg/ml. Aliquots of 1 ml were taken at 30 and 60 s and 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 10 min. Each aliquot was diluted 1:10 and measured on a FS45 fluorospectrometer (Perkin-Elmer, United Kingdom) at an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and an emission wavelength of 600 nm.

The efflux of ethidium bromide was measured by inoculating 3 ml of fresh LB broth with 4% of an overnight culture of strain SL1344, and the culture was incubated until the OD600 reached 0.7 ± 0.02. Ethidium bromide (25 μM; final concentration, 1 μg/ml) with or without 100 μM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each aliquot (to inhibit any efflux and to ensure a maximum intracellular concentration of ethidium bromide), and the aliquots were incubated at 20°C with stirring for 20 min. After centrifugation at 1,500 × g at 4°C, the supernatant was decanted and the pellet was resuspended in 1 M sodium phosphate buffer with 5% glucose to energize the cells. A total of 180 μl of each aliquot was added to six wells in a black microtiter 96-well tray, and after 140 s chlorpromazine was added at 200 μg/ml to three of the six biological repeats. The fluorescence at 600 nm was measured with a Fluostar fluorescent spectrometer (BMG Labtech, United Kingdom). The mean values from each biological and technical replicate were determined. The data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel software. The standard deviation was calculated and two-tailed paired Student's t tests were performed to assess error and significance.

Organic solvent tolerance assay.

Organic solvent tolerance assays were adapted from a method described previously (5). Briefly, 5 μl of a 1:100 dilution of an overnight culture of the test strain was spotted onto a dried LB agar surface and overlaid with 5 mm of hexane or cyclohexane (both from Sigma). The plates were sealed to prevent evaporation and were incubated for 24 h at 30°C before they were scored for growth.

RESULTS

The PM system reveals that disruption of acrB and tolC confers susceptibility to a hitherto unsuspected wide range of compounds.

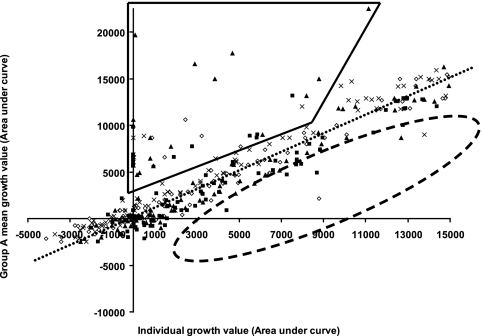

The PM system measures the ability of bacteria to grow under a range of different conditions. In this study, strains lacking a component of an RND efflux pump or a transcriptional activator previously indicated to be involved in MDR in E. coli or Salmonella serovar enterica were exposed to a variety of different compounds, including some known antimicrobials, in plates PM11a to PM20. The PM system allows the parallel testing of whether the growth of any of these strains compared to that of the parental strain, SL1344, was different. This technique was chosen as it allowed comparison of the growth of eight strains in parallel in the presence of 240 compounds. Before tests were performed with the PM system, no significant differences in the growth kinetics of any of the strains were observed. The mean generation time of each strain in LB medium was 31.7 ± 1.4 min. No overgrowth of any strain at stationary phase was seen (data not shown). The most striking observation seen in the PM system was the “clustering” of the responses of four of the mutants, the marA::aph (strain L101), ramA::aph (strain L103), acrD::aph (strain L106), and ΔacrF (strain L561) strains, to a large proportion of the compounds tested, in which all grew better than the parental (wild-type) strain, strain SL1344 (Fig. 1). In the presence of the same compounds, L108 (tolC::aph) and L644 (ΔacrB) consistently grew more poorly than SL1344. While the presence of the aph gene used to disrupt the target gene conferred the expected resistance to kanamycin and related antibiotics, the wide range of other compounds in the presence of which the strains showed altered growth was surprising. Of the 240 agents screened, the marA::aph, ramA::aph, acrD::aph, and ΔacrF strains grew better than SL1344 in the presence of 56 (23%) agents over two or more concentrations. Of those 56 agents, the tolC::aph and ΔacrB strains grew more poorly in the presence of 48 (86%) (Table 2). These included antibiotics of different classes, dyes, detergents, and biocides, 35 of which a literature search indicated have not previously been described as substrates of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump complex. Furthermore, the tolC::aph strain grew extremely poorly in the presence of more compounds; of the 48 compounds in the presence of which both the tolC::aph and the ΔacrB strains grew poorly, the tolC::aph strain grew particularly poorly in the presence of 11 (Table 3). It was also observed that the ramA::aph strain grew particularly poorly in the presence of several similar agents: amitriptyline, chlorpromazine, sanguinarine, and thioridazine.

FIG. 1.

PM growth data showing clustering of the strains which grew better (enclosed by black lines) or more poorly (enclosed by dashed lines). The dotted line indicates the mean growth of these four strains (group A) compared with of SL1344 in the presence different compounds; ⋄, L561 (ΔacrF); ▪, L130 (marA::aph); ▴, L133 (ramA::aph); ×, L106 (acrD::aph).

TABLE 2.

Compounds in which marA::aph, ramA::aph, acrD::aph, and ΔacrF strains demonstrated better growth than wild-type Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344, whereas tolC::aph and ΔacrB showed hypersusceptibility

| Compound class | Namea |

|---|---|

| Aminoglycoside | O/129b |

| Kanamycin | |

| Neomycin | |

| Paromomycin | |

| β-Lactam | Amoxicillin |

| Azlocillin | |

| Cefamandole | |

| Cefotaxime | |

| Cefuroxime | |

| Cloxacillin | |

| Nafcillin | |

| Oxacillin | |

| Phenethicillin | |

| Coumarin | Novobiocin |

| Folate inhibitor | Trimethoprim |

| Glycopeptide | Bleomycin |

| Macrolide | Erythromycin |

| Josamycin | |

| Lincomycin | |

| Oleandomycin | |

| Rifamycin SV | |

| Spiramycin | |

| Troleandomycin | |

| Tylosin | |

| Nitroamidazole | Ornidazole |

| Nitrofuran | Furaltadone |

| Nitrofurazone | |

| Peptidyl nucleoside | Puromycin |

| Phenicol | Chloramphenicol |

| Quinolone | Ciprofloxacin |

| Lomefloxacin | |

| Norfloxacin | |

| Steroid | Fusidic acid |

| Tetracycline | Chlortetracycline |

| Demeclocyline | |

| Dye | Crystal violet |

| Iodonitro tetrazolium violet | |

| Tetrazolium violet | |

| Acriflavine | |

| Detergent | Diaminobenzidine |

| Phenothiazine | Thioridazine |

| Chlorpromazine | |

| Trifluoperazine | |

| Benzophenanthridine | Sanguinarine |

| Chelerythrine | |

| Biocide | Dodine |

| Domiphen bromide | |

| Dequalinium | |

| Cu, Zn ion chelator | Chloroquinadol |

| Clioquinol | |

| NSAIDc | Ketoprofen |

| Anticholinergic | Orphenadrine |

| TCAd | Amitriptyline |

Boldface indicates that the compound was not previously described as a substrate of AcrAB-TolC.

Aminoglycoside derivative.

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

TABLE 3.

Agents in which poor growth of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344 tolC::aph compared to that for ΔacrB was observed

| Name | Compound class |

|---|---|

| O/129a | Aminoglycoside derivative |

| Orphenadrine | Cholinergic antagonist |

| 5-Chloro-7-iodo-8-hydroxyquinoline | Cu, Zn chelator |

| 5,7-Dichloro-8-hydroxyquinaldine | Cu, Zn chelator |

| Amitriptyline | Norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| Chlorpromazine | Phenothiazine |

| Trifluoperazine | Phenothiazine |

| Dequalinium | Ion channel inhibitor |

| Lincomycin | Lincosamide |

| Chelerythrine | Protein kinase C inhibitor (benzophenanthridine) |

| Ketoprofen | NSAIDb |

Aminoglycoside derivative.

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Phenothiazines are synergistic with some common antimicrobial agents.

The five phenothiazines tested, selected on the basis of the results obtained with the PM system, had poor activities against strain SL1344 (Table 4), other strains of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium, and the NCTC type strains of 10 other serovars of Salmonella serovar enterica (data not shown). The MICs ranged from 512 to ≥1,024 μg/ml. The hypersusceptibilities to phenothiazines of mutants of SL1344 in which acrB or tolC was inactivated were confirmed. Both strains were 16- to 32-fold more susceptible to thioridazine, trifluoperazine, and chlorpromazine (Table 4). Mutants in which acrD, acrF, or ramA had been inactivated were fourfold more susceptible to chlorpromazine; and those in which marA and soxS had been inactivated were twofold more susceptible.

TABLE 4.

MICs of phenothiazines and related compounds to the strains in this study

| Strain | MICa (μg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THI | TRI | AMI | CPZ | ORP | |

| SL1344 | >1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 512 | 1,024 |

| acrB::aph | 32 | 64 | 256 | 32 | 1,024 |

| acrD::aph | >1,024 | 1,024 | 1,024 | 128 | 1,024 |

| acrF::aph | >1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 128 | 1,024 |

| tolC::aph | 32 | 32 | 256 | 32 | 1,024 |

| marA::aph | >1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 256 | 1,024 |

| soxS::aph | >1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 256 | 1,024 |

| ramA::aph | >1,024 | 1,024 | 512 | 128 | 1,024 |

Boldface indicates a more than twofold decrease in the MIC. THI, thioridazine; TRI, trifluoperazine; AMI, amitriptyline; CPZ, chlorpromazine; ORP, orphenadrine.

Four of the phenothiazines were tested in combination with six antimicrobial agents for synergy against Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344. At 100 μg/ml, chlorpromazine had no discernible effect. However, at 200 μg/ml, the MICs of nalidixic acid, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and ethidium bromide were significantly reduced. No synergistic effect was observed with the other three phenothiazines tested, except for amitriptyline (200 μg/ml) and norfloxacin (Table 5). The synergy of chlorpromazine with two of the antimicrobial agents, norfloxacin and ethidium bromide, was confirmed with the other strains of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and the NCTC type strains of 10 other Salmonella serovars (Table 6).

TABLE 5.

MICs of various compounds for wild-type Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344 exposed to the various compounds and phenothiazines in combinationa

| Compound | Phenothiazine concn (μg/ml) | MICb (μg/ml) of the following compound at the indicated concn (μg/ml):

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPZ

|

AMI

|

THI

|

TRI

|

||||||

| 100 | 200 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 200 | ||

| Nal | 4 | 8 | 0.015 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 | 4 | 4 |

| Nor | 0.25 | 0.5 | <0.007 | 0.25 | <0.007 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Cip | 0.12 | 0.06 | <0.007 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Chl | 4 | >4 | 0.015 | >4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tet | 2 | 8 | 0.25 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| EtBr | 1024 | 1,024 | 8 | 1,024 | 1,024 | 2,048 | 1,024 | 1,024 | 1,024 |

The synergistic action of orphenadrine was not tested because it was not observed to have antimicrobial action. CPZ, chlorpromazine; AMI, amitriptyline; THI, thioridazine; TRI, trifluoperazine; Nal, nalidixic acid; Nor, norfloxacin; Cip, ciprofloxacin; Chl, chloramphenicol; Tet, tetracycline; EtBr, ethidium bromide.

Boldface indicates a more than twofold decrease in the MIC.

TABLE 6.

Synergistic activity of chlorpromazine against various Salmonella serovars

| Serovar | MICa (μg/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nor | Nor + CPZ | EtBr | EtBr + CPZ | |

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344 | 0.06 | 0.008 | 1024 | 8 |

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium LT2 | 0.06 | 0.003 | 1,024 | 0.5 |

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium 14028S | 0.06 | 0.006 | 2,048 | 16 |

| Salmonella serovar Binza | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 128 |

| Salmonella serovar Enteritidis | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 0.5 |

| Salmonella serovar Hadar | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 0.5 |

| Salmonella serovar Haifa | 0.06 | 0.004 | 512 | 0.5 |

| Salmonella serovar Heidelberg | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 0.5 |

| Salmonella serovar Kedougou | 0.06 | 0.004 | 512 | 256 |

| Salmonella serovar Mbandaka | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 0.5 |

| Salmonella serovar Montevideo | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 512 |

| Salmonella serovar Newport | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 128 |

| Salmonella serovar Virchow | 0.06 | 0.004 | 1,024 | 64 |

Boldface indicates a more than twofold decrease in the MIC. Nor, norfloxacin; CPZ, chlorpromazine; EtBr, ethidium bromide.

Chlorpromazine appears to have efflux pump inhibitor properties.

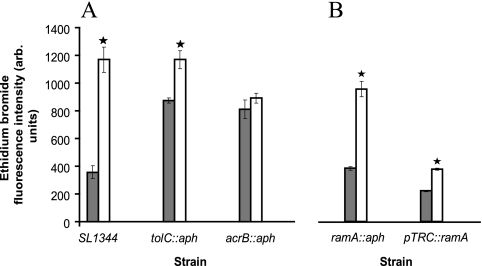

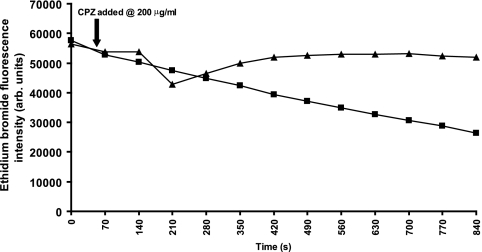

The hypersusceptibilities to chlorpromazine of mutants in which acrB or tolC had been inactivated and the synergy of this agent with antimicrobial agents suggested that chlorpromazine could be an efflux pump inhibitor and interact with a component(s) of the AcrAB-TolC tripartite efflux pump. The levels of accumulation of ethidium bromide by these strains compared with that by parental strain SL1344 were determined in the presence and the absence of chlorpromazine (Fig. 2A). Unfortunately, the level of accumulation of ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin (or any other fluoroquinolone) could not be determined, as chlorpromazine quenched the fluorescence of these agents. In the presence of chlorpromazine (200 μg/ml), SL1344 accumulated 3.6-fold more ethidium bromide than it did without chlorpromazine. When tolC or acrB was inactivated, each mutant accumulated more than double the amount of ethidium bromide than the parental strain, SL1344. Chlorpromazine had no significant effect upon the level of accumulation by the mutant in which acrB was inactivated. However, for the mutant in which tolC had been inactivated, addition of chlorpromazine increased the level of ethidium bromide accumulation to the same level seen for SL1344 in the presence of chlorpromazine. In an assay determining the efflux of ethidium bromide, chlorpromazine prevented the efflux of this agent from SL1344 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Accumulation of ethidium bromide in the presence of chlorpromazine at 200 μg/ml (unfilled bars) and in the absence of chlorpromazine (gray bars). *, statistically significant increase in accumulation in the presence of chlorpromazine (P < 0.05). All units are arbitrary (arb.).

FIG. 3.

Efflux of ethidium bromide from Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344 in the presence and absence of chlorpromazine (CPZ) at 200 μg/ml. ▴, SL1344; ▪, SL1344 plus chlorpromazine at 200 μg/ml. Fluorescence units are arbitrary (arb.).

Overproduction of ramA confers MDR.

The data obtained with the PM system also indicated that when ramA was inactivated, this mutant was more susceptible to inhibition by phenothiazines. This was confirmed by MIC testing, which revealed that SL1344 ramA::aph was fourfold more susceptible to chlorpromazine then SL1344. While mutants in which marA or soxS were inactivated were also more susceptible to chlorpromazine, the decrease in the MIC was modest (Table 4). ramA has previously been implicated as having a role in MDR in Salmonella, because when this gene was cloned from clinical isolates of Salmonella serovar Paratyphi or Salmonella serovar Typhimurium into E. coli, decreased susceptibility or modest MDR was conferred, and the phenotype was similar to that seen when marA or soxS is overproduced in E. coli (30, 36). However, inactivation of ramA in MDR clinical isolates of Salmonella conferred only a modest increase in antibiotic susceptibility (30), and so a clear role for ramA in MDR in Salmonella has not been defined. This may be because of the confounding influence of other mechanisms of resistance in the clinical isolates, the method of testing of antimicrobial susceptibility, or the agents tested (30, 31). To carefully dissect the role of ramA in MDR in Salmonella and any effect of chlorpromazine, in the present study isogenic strains were constructed. ramA was inactivated in SL1344; and then plasmid-mediated ramA, under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter, was introduced to give strain L786. In the absence of IPTG (minimal induction), L786 expressed ramA 1.74-fold more than SL1344 did. In the presence of 1 mM IPTG, the level of expression was 38-fold higher in L786 than in SL1344. The MICs of a wide range of antimicrobial agents for these strains were determined. The MICs of those agents typically associated with the MDR phenotype conferred by the overproduction of marA or soxS in E. coli were unaffected when ramA was inactivated. Only for acriflavine was any change in the MIC observed (Table 7). However, it was noted that the inactivated strain became intolerant to hexane. The overproduction of ramA in L786 (SL1344 ramA::aph-pTRChisA::ramA) and induction with IPTG conferred an MDR phenotype (Table 7). In addition, L786 was tolerant to both hexane and cyclohexane. The inactivation or overproduction of ramA had no effect on the MIC of SDS, bile, sodium deoxycholate, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, or rhodamine 6G.

TABLE 7.

Susceptibility of wild-type Salmonella serovar Typhimurium SL1344 and a ramA-overexpressing strain to various antibiotics, dyes, detergents, and organic solvents in the presence and absence of chlorpromazine

| Strain | MICa (μg/ml)

|

Sensitivityb

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPZ | Cip | Nal | Nor | Chl | Tet | EtBr | Tric | Acr | CV | Nov | Hexane | Cyclohexane | |

| SL1344 | 512 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.25 | 4 | 2 | 2,048 | 0.12 | 512 | 2 | 512 | Tc | S |

| SL1344 with CPZ | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 8 | 0-3 | 512 | 1 | 64 | S | S | |

| L133d | 256 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.25 | 4 | 2 | 1,024 | 0.12 | 256 | 2 | 256 | S | S |

| L133 with CPZ | NDe | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | S | S |

| L786f without IPTG | 512 | 0.03 | 16 | 0.25 | 8 | 4 | 2,048 | 0.25 | 256 | 2 | 512 | T | S |

| L786 with IPTG | 512 | 0.03 | 64 | 0.25 | 32 | 16 | 2,048 | 1 | 512 | 2 | 1,024 | T | T |

| L786 without IPTG and with CPZ | 0.015 | 16 | 0.25 | 16 | 8 | 512 | 0.25 | 512 | 0.5 | 512 | T | T | |

Italics indicate a more than twofold increase in the MIC compared to that for SL1344; boldface indicates a decrease in the MIC compared to that for L786 alone. CPZ, chlorpromazine; Cip, ciprofloxacin; Nal, nalidixic acid; Nor, norfloxacin; Chl, chloramphenicol; Tet, tetracycline; EtBr, ethidium bromide, Tric, triclosan; Acr, acridine orange; CV, crystal violet; NOV, novobiocin.

T, tolerant to organic solvent; S, sensitive to organic solvent.

Addition of chlorpromazine also conferred hexane sensitivity in SL1344.

L133 is a ramA::aph strain.

ND, MIC not determined as the MIC for chlorpromazine was <200 μg/ml.

L786 is a ramA::aph-pTRChisA::ramA strain.

ramA affects expression of acrB.

It was hypothesized that acrB was part of the ramA regulon and that the MDR in strain L786 was due to the overproduction of AcrAB-TolC. When ramA was inactivated (strain L133), acrB was expressed at one-fifth the level it was expressed in the parental strain, SL1344 (Table 8). In the absence of acrB (strain L110), ramA was overproduced. In the absence of IPTG, acrB was expressed in L786 at the same level as it was in SL1344 (data not shown). However, in the presence of IPTG, the level of acrB expression was increased by 15-fold. The level of accumulation of ethidium bromide in the mutant in which ramA had been inactivated (strain L133) was similar to that in parental strain SL1344 (Fig. 2B). Similarly, upon addition of chlorpromazine, the level of ethidium bromide accumulation increased. When ramA was overproduced, the level of accumulation of ethidium bromide was less than that in SL1344, with chlorpromazine having little effect.

TABLE 8.

Comparison of expression of ramA and acrB with or without chlorpromazine at 200 μg/ml

| Strain | Genotype | Level of expressiona

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ramA

|

acrB

|

||||

| Without CPZ | With CPZ | Without CPZ | With CPZ | ||

| SL1344 | 1 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 ± 0.04 | |

| L133 | ramA::aph | ND | ND | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| L786 | ramA::aph pTRC hisA::ramA | 37.6 ± 0.2b | ND | 14.9 ± 0.2b | ND |

| L110 | acrB::aph | 3.9 ± 0.04 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | ND | ND |

The data were obtained by comparative PCR. The level of gene expression by the reference strain value was set equal to an arbitrary value of 1, to which the data for the other strains were normalized. Values less than zero reflect the reciprocal of the fold decrease; e.g., 0.2 indicates a fivefold decrease. CPZ, chlorpromazine; ND, not detected.

Values were obtained in the presence of IPTG.

Chlorpromazine induces expression of ramA but represses acrB expression.

To determine whether chlorpromazine induced the expression of ramA or acrB, or both, an SL1344 strain in which ramA or acrB had been inactivated was exposed to chlorpromazine (200 μg/ml) for 30 min at mid-logarithmic phase of growth. In SL1344, 2.6-fold more ramA was produced and there was a concomitant decrease in the level of expression of acrB (Table 8). When ramA was inactivated (strain L133), chlorpromazine exposure increased the level of expression of acrB by fourfold compared with that in the absence of chlorpromazine. When acrB was inactivated (strain L110), chlorpromazine exposure had little effect on ramA expression. In the presence of chlorpromazine, the MICs of ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ethidium bromide, triclosan, and crystal violet were reduced by at least twofold (Table 7). However, addition of chlorpromazine to L786 did not restore sensitivity to hexane or cyclohexane.

DISCUSSION

The PM system was used to explore the activities of a wide range of antimicrobial and nonantimicrobial compounds against mutants in which components of an efflux pump had been inactivated or genes previously indicated to control or influence the expression of acrAB in E. coli had been inactivated. The hypersusceptibility to a wide range of agents of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium mutants in which acrB or tolC had been inactivated or deleted was confirmed previously (8, 14, 24). In addition, in the present study these mutants were also shown to be hypersusceptible to antimicrobials not previously considered to be substrates of AcrAB-TolC and additionally to nonantimicrobial classes of compounds, such as the phenothiazines. The mutant in which tolC was inactivated was hypersusceptible to more agents than the mutant in which acrB had been deleted, suggesting that these additional agents are exported by pumps other then AcrB and also use TolC as the outer membrane protein channel. We have previously shown that when acrD or acrF is inactivated, there is an increased level of expression of acrB, presumably to compensate for the lack of the transporter (14). This may explain the improved growth of the two mutants seen in the presence of the phenothiazines, whereas the mutant in which acrB was inactivated grew more slowly. Inactivation of the transcriptional regulators marA and ramA typically gave rise to better growth in the presence of compounds in which the tolC or acrB mutants grew poorly. This may be because the lack of these transcriptional regulators allows the expression of genes which are normally repressed (7). It has been observed in E. coli that strains in which efflux pump genes have been deleted can overgrow compared to the level of growth of wild-type strains, and this is postulated to be due to the lack of the export of quorum-sensing factors (35). However, no overgrowth was observed in this study, and no growth differences between SL1344 (the parental strain) and the mutants in which acrB or tolC had been inactivated were seen. This is likely due to the differences in quorum sensing between E. coli and Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (2). Salmonella serovar Typhimurium mutants in which tolC, acrB, or ramA had been inactivated were particularly susceptible to phenothiazines and compounds with similar modes of action, such as chlorpromazine. Because this class of agents was previously identified to possess potential activity and synergistic activity with some antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus (3, 15), we focused further attention on these compounds. Furthermore, phenothiazines are thought to inhibit NorA, an MFS efflux pump in S. aureus (15). More recently, phenothiazines have been shown to have synergistic activity with antimicrobials against Burkholderia pseudomallei (11). In the present study, chlorpromazine was shown to be synergistic with several agents of different chemical classes, and amitriptyline was shown to be synergistic with norfloxacin against Salmonella. These data suggest that phenothiazines could act as efflux pump inhibitors. In support of this hypothesis, it was found that chlorpromazine increased the concentration of ethidium bromide that accumulated in all mutants except the strain in which acrB had been inactivated. Likewise, the efflux of ethidium bromide by SL1344 (the parental wild-type strain) was decreased in the presence of chlorpromazine.

The PM system also revealed that the mutant in which ramA had been inactivated was hypersusceptible to phenothiazines. As it was previously suggested that when ramA is overexpressed it could confer MDR, we first sought to construct a set of isogenic strains which had a defined level of overexpression of ramA and then to use the strains to explore the interaction with chlorpromazine. First, the overexpression of ramA was shown to confer MDR in Salmonella. These data confirm and extend those of van den Straaten et al. (30) and also those most recently obtained by Abouzeed et al. (1). When ramA was highly expressed, there was a concomitant overexpression of acrB. These data indicate that acrB is within the regulon of ramA and that the overexpression of ramA confers MDR via the overproduction of the AcrB transporter. Of interest, it was observed that when ramA was inactivated, the expression of acrB was significantly reduced. Likewise, when acrB was inactivated, there was an effect upon the expression of ramA; in this case, there was a fourfold increase in the level of expression. These data indicate that there is a mechanism within the bacterial cell for detection of both the level of acrB expression and the level of ramA expression and that regulation is not a one-way process from ramA to acrB. Second, we showed that the level of expression of ramA was important in the determination of whether the strain was MDR or not; for instance, in the absence of IPTG, ramA was expressed at low levels and there was no overexpression of acrB and very modest MDR.

Although it has previously been suggested that chlorpromazine and other phenothiazine compounds are efflux pump inhibitors, no direct biochemical data have been provided to show an interaction between these compounds and a transporter protein. Another hypothesis that may explain these data is that chlorpromazine affects the expression of the gene(s) involved in regulating the expression of efflux. Therefore, we explored the effect of chlorpromazine upon the expression of ramA and acrB in the constructs in which ramA was either inactivated or overproduced. It was found that chlorpromazine induced the expression of ramA in wild-type antibiotic-sensitive strain SL1344 and that there was a concomitant decrease in the level of production of acrB. These data suggest that chlorpromazine acts on ramA and acrB separately and that chlorpromazine induces ramA but that it also represses the expression of acrB. The repression of acrB correlated well with the increased level of accumulation which had previously been hypothesized to be due to efflux inhibition. Our data suggest that, in fact, chlorpromazine acts to repress the expression of the efflux pump gene, and so the efflux pump is produced at a lower level which is insufficient to export the antimicrobial, hence increasing the concentration accumulated. The modest induction of ramA by chlorpromazine was at a level that we have shown was insufficient to induce the expression of acrB and to confer MDR.

An association between organic solvent tolerance (cyclohexane) and MDR has previously been shown when marA and/or acrB was overproduced in E. coli (5). A similar association has been made for Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (32). This has led many to consider that cyclohexane tolerance can be used as a marker for increased efflux via acrB and/or that this indicates a marA mutant. We observed that the high-level overexpression of ramA conferred tolerance to cyclohexane and that the phenotype of this overexpressing Salmonella serovar Typhimurium mutant was the same as that previously associated with the overexpression of marA in E. coli (33). Although addition of chlorpromazine rendered SL1344 sensitive to hexane, it did not affect the hexane or cyclohexane tolerance shown by the overexpressing strain (strain L786) or a previously characterized laboratory-selected cyclohexane-tolerant mutant (unpublished data). Therefore, for Salmonella, cyclohexane tolerance may be an indicator of the overproduction of ramA.

In summary, this study has revealed that the PM screen is a valuable tool in the search for compounds that can inhibit efflux (in this case, by downregulating the production of the efflux pump) and shows the potential to identify a pharmaceutical compound already in use for the treatment of other human diseases as a possible agent for use in combination with conventional antimicrobial drugs. As the search for ways to reverse antimicrobial resistance continues, the identification of molecules that are already used within human medicine will make the regulatory process for combination treatment more straightforward. The PM screen indicated that the phenothiazines are inhibitors of efflux, and from work done by others with S. aureus and B. pseudomallei, they may also act in a similar fashion in these species. Finally, although ramA had previously been postulated to confer MDR in Salmonella and K. pneumoniae, in this study we have both confirmed the hypothesis that MDR is conferred by overproduction of acrB and shown that a defined level of overproduction of ramA is required to obtain the overproduction of acrB at a sufficient level to export antimicrobials.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following people: Kathy Kang and Aaron Johnson at The Institute for Genomic Research, where the PM experiments were performed; Tahar van der Straaten for the kind donation of pTRChisA::ramA; Mark Webber for reading the manuscript; and Alexander Mott for the growth data.

This work was supported by the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation nonrestrictive grant in infectious diseases to L.J.V.P. The visit to TIGR was funded by a Wellcome Trust Value in People Award to A.M.B. Work on multiple-antibiotic resistance in Salmonella serovar Typhimurium is supported in L.J.V.P.'s laboratory by MRC grant GO501415.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abouzeed, Y. M., S. Baucheron, and A. Cloeckaert. 2008. ramR mutations involved in efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2428-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmer, B. M., J. van Reeuwijk, C. D. Timmers, P. J. Valentine, and F. Heffron. 1998. Salmonella typhimurium encodes an SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor of the LuxR family, that regulates genes on the virulence plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 180:1185-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaral, L., M. Viveiros, and J. Molnar. 2004. Antimicrobial activity of phenothiazines. In Vivo 18:725-731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews, J. M. 2001. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48(Suppl. 1):5-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asako, H., H. Nakajima, K. Kobayashi, M. Kobayashi, and R. Aono. 1997. Organic solvent tolerance and antibiotic resistance increased by overexpression of marA in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1428-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey, A. M., M. A. Webber, and L. J. V. Piddock. 2006. Medium plays a role in determining expression of acrB, marA, and soxS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1071-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbosa, T. M., and S. B. Levy. 2000. Differential expression of over 60 chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of MarA. J. Bacteriol. 182:3467-3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baucheron, S., S. Tyler, D. Boyd, M. R. Mulvey, E. Chaslus-Dancla, and A. Cloeckaert. 2004. AcrAB-TolC directs efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3729-3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baucheron, S., C. Mouline, K. Praud, E. Chaslus-Dancla, and A. Cloeckaert. 2005. TolC but not AcrB is essential for multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium colonization of chicks. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:707-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckley, A. M., M. A. Webber, S. Cooles, L. P. Randall, R. M. La Ragione, M. J. Woodward, and L. J. Piddock. 2004. The AcrAB-TolC efflux system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium plays a role in pathogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 5:847-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan, Y. Y., Y. M. Ong, and K. L. Chua. 2007. Synergistic interaction between phenothiazines and antimicrobial agents against Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:623-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Cristobal, R. E., P. A. Vincent, and R. A. Salomon. 2006. Multidrug resistance pump AcrAB-TolC is required for high-level, Tet(A)-mediated tetracycline resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaves, D. J., V. Ricci, and L. J. Piddock. 2004. Expression of acrB, acrF, acrD, marA, and soxS in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: role in multiple antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1145-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaatz, G. W., V. V. Moudgal, S. M. Seo, and J. E. Kristiansen. 2003. Phenothiazines and thioxanthenes inhibit multidrug efflux pump activity in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:719-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeney, D., A. Ruzin, and P. A. Bradford. 2007. RamA, a transcriptional regulator, and AcrAB, an RND-type efflux pump, are associated with decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Enterobacter cloacae. Microb. Drug Resist. 13:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keeney, D., A. Ruzin, F. McAleese, E. Murphey, and P. A. Bradford. 2008. MarA-mediated overexpression of the AcrAB efflux pump results in decreased susceptibility to tigecycline in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacroix, F. J., A. Cloeckaert, O. Grepinet, C. Pinault, M. Y. Popoff, H. Waxin, and P. Pardon. 1996. Salmonella Typhimurium acrB-like gene: identification and role in resistance to biliary salts and detergents and in murine infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 135:161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, A., W. Mao, M. S. Warren, A. Mistry, K. Hoshino, R. Okumura, H. Ishida, and O. Lomovskaya. 2000. Interplay between efflux pumps may provide either additive or multiplicative effects on drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 182:3142-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy, S. B. 2002. Active efflux, a common mechanism for biocide and antibiotic resistance. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 2002:65S-71S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markham, P. N., E. Westhaus, K. Klyachko, M. E. Johnson, and A. A. Neyfakh. 1999. Multiple novel inhibitors of the NorA multidrug transporter of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2404-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikaido, H. 1996. Multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:5853-5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikaido, H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:593-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishino, K., T. Latifi, and E. A. Groisman. 2006. Virulence and drug resistance roles of multidrug efflux systems of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 59:126-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricci, V., P. Tzakas, A. Buckley, and L. J. Piddock. 2006. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains are difficult to select in the absence of AcrB and TolC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:38-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruzin, A., M. A. Visalli, D. Keeney, and P. A. Bradford. 2005. Influence of transcriptional activator ramA on expression of multidrug efflux pump acrAB and tigecycline susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1017-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone, B. J. and V. L. Miller. 1995. Salmonella enteritidis has a homologue of tolC that is required for virulence in BALB/c mice. Mol. Microbiol. 17:701-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulavik, M. C., C. Houseweart, C. Cramer, N. Jiwani, N. Murgolo, J. Greene, B. DiDomenico, K. J. Shaw, G. H. Miller, R. Hare, and G. Shimer. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Escherichia coli strains lacking multidrug efflux pump genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1126-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thanassi, D. G., L. W. Cheng, and H. Nikaido. 1997. Active efflux of bile salts by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:2512-2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Straaten, S. T., R. Janssen, D. J. Mevius, and J. T. van Dissel. 2004. Salmonella gene rma (ramA) and multiple-drug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2292-2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Straaten, S. T., L. Zulianello, A. van Diepen, D. L. Granger, R. Janssen, and J. T. van Dissel. 2004. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium RamA, intracellular oxidative stress response, and bacterial virulence. Infect. Immun. 72:996-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webber, M. A., A. M. Buckley, L. P. Randall, M. J. Woodward, and L. J. Piddock. 2006. Overexpression of marA, soxS and acrB in veterinary isolates of Salmonella enterica rarely correlates with cyclohexane tolerance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White, D. G., J. D. Goldman, B. Demple, and S. B. Levy. 1997. Role of the acrAB locus in organic solvent tolerance mediated by expression of marA, soxS, or robA in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6122-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wray, C., and W. J. Sojka. 1978. Experimental Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 25:139-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, S., C. R. Lopez, and E. L. Zechiedrich. 2006. Quorum sensing and multidrug transporters in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2386-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yassien, M. A., H. E. Ewis, C. D. Lu, and A. T. Abdelal. 2002. Molecular cloning and characterization of the Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi B rma gene, which confers multiple drug resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:360-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, L., X. H. Lei, B. R. Bochner, and B. L. Wanner. 2003. Phenotype microarray analysis of Escherichia coli K-12 mutants with deletions of all two-component systems. J. Bacteriol. 185:4956-4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]