Abstract

Adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) are nucleotide analogs that inhibit the replication of wild-type hepatitis B virus (HBV) and lamivudine (3TC)-resistant virus in HBV-infected patients, including those who are coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus. The combination of ADV or TDF with other nucleoside analogs is a proposed strategy for managing antiviral drug resistance during the treatment of chronic HBV infection. The antiviral effect of oral ADV or TDF, alone or in combination with 3TC or emtricitabine (FTC), against chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) infection was evaluated in a placebo-controlled study in the woodchuck, an established and predictive model for antiviral therapy. Once-daily treatment for 48 weeks with ADV plus 3TC or TDF plus FTC significantly reduced serum WHV viremia levels from the pretreatment level by 6.2 log10 and 6.1 log10 genome equivalents/ml serum, respectively, followed by TDF plus 3TC (5.6 log10 genome equivalents/ml), ADV alone (4.8 log10 genome equivalents/ml), ADV plus FTC (one survivor) (4.4 log10 genome equivalents/ml), TDF alone (2.9 log10 genome equivalents/ml), 3TC alone (2.7 log10 genome equivalents/ml), and FTC alone (2.0 log10 genome equivalents/ml). Individual woodchucks across all treatment groups also demonstrated pronounced declines in serum WHV surface antigen, characteristically accompanied by declines in hepatic WHV replication and the hepatic expression of WHV antigens. Most woodchucks had prompt recrudescence of WHV replication after drug withdrawal, but individual woodchucks across treatment groups had sustained effects. No signs of toxicity were observed for any of the drugs or drug combinations administered. In conclusion, the oral administration of 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF alone and in combination was safe and effective in the woodchuck model of HBV infection.

Chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major public health problem and is responsible for 1.2 million deaths per year worldwide (64). It is estimated that more than 2 billion people have serological evidence of previous or current HBV infection, and over 350 million people are chronic carriers of HBV (64). Carriers of HBV are at high risk of developing chronic hepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Although safe and effective prophylactic vaccines against HBV are available, improvements in drug and/or immunotherapeutic strategies for the treatment of chronic HBV infection are still needed. Therapy with alpha interferon and nucleoside analogs alone or in combination can be effective against HBV; however, side effects of interferon and the emergence of nucleoside-resistant mutants often limit treatment outcomes (34).

Lamivudine (3TC) was the first nucleoside analog licensed for the treatment of chronic HBV infection. Although 3TC is safe and effective, its therapeutic value is limited by the time-dependent development of drug-resistant HBV mutants (32); therefore, various combination therapies have long been proposed to counter drug resistance in HBV infection. More recently, the nucleotide analog adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) was licensed for the treatment of HBV infection and was shown to inhibit the replication of 3TC-resistant virus mutants in patients also treated with 3TC (1, 3, 4, 16, 37, 47, 66). In fact, in chronic HBV carriers, even monotherapy with ADV for up to 5 years had a high degree of safety and efficacy, and resistant mutants developed less frequently than in parallel studies with 3TC alone (2, 19, 35, 48, 65). Treatment for 48 weeks with two different doses of ADV reduced viremia by 3.5 to 4.8 log10 genome equivalents/ml serum in patients with chronic HBV infection (35). A similar decrease in serum HBV DNA of 3.5 and 3.9 log10 genome equivalents/ml was demonstrated in two other studies after 48 weeks of treatment with ADV (20, 51). Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), a nucleotide analog approved for the therapy of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), was also effective in HBV-infected patients who developed 3TC resistance (5, 7, 43, 45, 50, 59, 61, 63). Treatment with TDF for 24 to 71 weeks in HIV-coinfected patients demonstrated that HBV DNA concentrations decreased by approximately 4 to 5 log10 genome equivalents/ml on average (5, 18, 31, 43, 45, 50, 62, 63). Furthermore, 12 months of TDF treatment of patients infected with 3TC-resistant HBV mutants led to average reductions in HBV DNA concentrations of 4.5 to 5.5 logs, which are similar to those observed in patients coinfected with HBV and HIV (30, 62, 63). Because ADV and TDF effectively inhibit the replication of 3TC-resistant HBV mutants in HBV-infected patients, it has been hypothesized that the coadministration of these drugs in combination with 3TC from the onset of treatment would prevent or significantly delay the emergence of 3TC-resistant HBV mutants. In fact, in tissue culture studies, the combination of ADV with 3TC, emtricitabine (FTC), and other nucleoside and nucleotide derivatives resulted in additive or synergistic interactions with no statistically significant antagonism (17, 52). Furthermore, combination therapy with TDF and 3TC for at least 12 months reduced HBV DNA concentrations by 4.5 log10 genome equivalents/ml in patients coinfected with HBV and HIV (25). Combination therapy with ADV and 3TC for up to 2 years in patients with chronic HBV infection reduced viremia by more than 3 log10 genome equivalents/ml (47, 49). In another study of patients with chronic HBV infection, 24 weeks of treatment with ADV in combination with 3TC reduced HBV DNA concentrations by 3.6 log10 genome equivalents/ml.

Woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) and its natural host, the Eastern woodchuck (Marmota monax), represent a well-characterized mammalian model for research on HBV, including the pathogenesis of acute and chronic HBV infection, as well as for the preclinical evaluation of the safety and efficacy of candidate antiviral drugs and therapeutic immunomodulators for the treatment of chronic HBV infection (39, 56) and the prevention of HCC (58). In particular, the results of drug efficacy studies in the woodchuck have been predictive of responses in patients chronically infected with HBV (27).

In pharmacodynamic studies of 3TC in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks, 3TC-resistant mutations in the B domain of the polymerase gene developed after treatment for 9 to 12 months, and there was an associated recrudescence of serum WHV DNA levels to pretreatment levels (22, 24, 27, 36, 55). The treatment of chronic WHV carriers with FTC for 4 weeks produced a short-term antiviral profile similar to that of 3TC (23, 29). The antiviral effects of ADV and TDF in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks were also tested, and moderate but significant antiviral activity was demonstrated after 12 and 4 weeks of treatment, respectively (14, 40).

In the present placebo-controlled study, antiviral activities in the woodchuck model for 48 weeks of treatment with 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF alone and in combination were determined. The results demonstrate that the combination of 3TC and ADV and that of FTC and TDF were most effective in suppressing viral replication during chronic infection with wild-type WHV. The observed antiviral activity and favorable safety profile in woodchucks following drug treatment with doses comparable to or higher than those used with humans support the continued clinical development of combination treatment regimens with ADV or TDF for the long-term treatment of chronic HBV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Woodchucks.

All experimental procedures involving woodchucks were performed under protocols approved by the Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Woodchucks were born to WHV-negative females and reared in environmentally controlled laboratory animal facilities at Cornell University. Woodchucks were inoculated at 3 days of age with 5 million woodchuck infectious doses of standardized WHV inoculums (WHV7P1 or cWHV7P2) (12). Woodchucks were selected as chronic WHV carriers on the basis of the persistent detection of WHV surface antigen (WHsAg) and WHV DNA in serum prior to the initiation of treatments. All animals were free of HCC at the beginning of the study as determined by hepatic ultrasound examination and normal serum activity of γ-glutamyl-transferase (GGT).

Drug.

FTC, ADV, and TDF were provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Durham, NC). 3TC (Epivir) was purchased from GlaxoSmithKline, Inc. (Philadelphia, PA). 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF alone and in combination were administered orally to woodchucks once daily for 48 weeks by dose syringe (57), with one exception: TDF was not administered to the TDF monotherapy group or to the TDF-plus-3TC and the TDF-plus-FTC combination therapy groups during week 43 of treatment for a total of 6 days because of a delay in drug supply. 3TC, ADV, and TDF were weighed and dissolved in isotonic saline; FTC was obtained as a solution in isotonic saline. Immediately prior to administration, all drugs were suspended in a semisynthetic liquid diet formulated for woodchucks (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA). The liquid diet alone was administered to control woodchucks daily as a placebo.

Antiviral study.

Forty-five adult woodchucks, all chronically infected with WHV, were stratified equally by age, sex, body weight, serum viral load, and serum GGT activity into nine treatment groups of five animals each. Woodchucks were treated daily with oral doses of 3TC (15 mg/kg of body weight per day), FTC (15 mg/kg per day), ADV (15 mg/kg per day), TDF (15 mg/kg per day), ADV plus 3TC (15 mg/kg per day each), ADV plus FTC (15 mg/kg per day each), TDF plus 3TC (15 mg/kg per day each), TDF plus FTC (15 mg/kg per day each), or vehicle alone as a placebo. The woodchucks were treated for 48 weeks (exceptions noted above) and were observed for an additional 12 weeks following the cessation of treatment with drugs and placebo.

Dosages used in the present study for the treatment of chronic WHV carrier woodchucks were shown previously to be effective and safe in other studies in woodchucks (14, 23, 24, 26, 36, 40, 55, 70, 71). On the basis of metabolic body size, the per-kilogram dose for woodchucks would be approximately three times that of the human dose. The standard therapeutic dose of 3TC for humans with chronic HBV infection is 100 mg per day or 1.43 mg/kg for a 70-kg patient. The scaled equivalent woodchuck dose would be 4.29 mg/kg, and the 15-mg/kg dose of 3TC used in the present study is approximately 3.5-fold higher than the clinical treatment dose in humans. The standard therapeutic dose of FTC for the treatment of chronic HBV infection in humans is 200 mg or 2.86 mg/kg for a 70-kg patient, and when scaled for woodchucks, the equivalent dose would be 8.58 mg/kg. The 15-mg/kg dose of FTC used in the present study is approximately 1.7-fold higher than the clinical treatment dose in humans. The standard therapeutic dose of ADV for humans with chronic HBV infection is 10 mg per day or 0.14 mg/kg for a 70-kg patient, and when scaled for woodchucks, the equivalent dose would be 0.43 mg/kg. The 15-mg/kg dose of ADV used in the present study is approximately 35-fold higher than the clinical treatment dose in humans. TDF has been shown to be safe and effective in humans with chronic HBV infection at therapeutic doses ranging from 75 to 300 mg/kg or 1.07 to 3.21 mg/kg for a 70-kg patient. The scaled equivalent woodchuck doses would be 3.21 to 12.86 mg/kg, and the 15-mg/kg dose of TDF used in the present study is approximately 1.2- to 4.7-fold higher than the clinical treatment dose in humans.

Blood samples were obtained for WHV DNA analysis and serological testing while animals were under general anesthesia (50 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine intramuscularly). Samples were taken prior to drug administration on the first day of treatment (“week 0”); at 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 days of drug treatment; at 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of drug treatment; and then monthly until the end of drug treatment at week 48. Thereafter, samples were obtained at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 weeks following the termination of treatment. The woodchucks were weighed each time they were anesthetized and bled, and drug dosages for individual woodchucks were based on the most recent body weight.

Serum WHV DNA was measured quantitatively by two different methods depending on the concentration: either by dot blot hybridization (assay sensitivity, ≥1.0 × 107 WHV genome equivalents per ml) or by real-time PCR (assay sensitivity, ≥1.0 × 103 WHV genome equivalents/ml), as previously described (38). Serum WHsAg, antibodies to WHV core antigen (anti-WHc), and antibodies to WHV surface antigen (anti-WHs) were determined with WHV-specific enzyme immunoassays (13) at the intervals described above.

Serum biochemical measurements were performed 2 weeks prior to drug administration, on the first day of treatment (“week 0”) prior to drug administration, every other week through week 12 of drug treatment, and then monthly until the end of drug treatment at week 48. Thereafter, measurements were performed at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 weeks following the termination of drug treatment. Complete blood counts were performed 2 weeks prior to drug administration; at 12, 36, and 48 weeks of drug treatment; and then at 12 weeks following the termination of drug treatment. Serum chemistry measurements included serum GGT, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH), total bilirubin, albumin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, Na+, K+, Cl−, bicarbonate, total serum iron, iron binding capacity, and percent iron saturation (57). Serum activities of AST, ALT, and SDH are markers of hepatocellular injury in woodchucks.

Liver biopsies were obtained prior to drug administration; at 12, 36, and 48 weeks of drug treatment; and then at 12 weeks following drug withdrawal. Biopsies were performed while the animals were under general anesthesia (50 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine intramuscularly) with 16-gauge Bard Biopty-Cut (C. R. Bard Inc., Covington, GA) disposable biopsy needles directed by ultrasound imaging (46, 57). Aliquots of biopsy specimens were fixed in phosphate-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological analysis (i.e., portal hepatitis, lobular hepatitis, bile duct proliferation, steatosis, and liver cell dysplasia) (46, 57). According to their severity, the specific lesions were graded on a scale of 0 to 4 (representing an absent lesion to the most severe lesion, respectively). Sections of these tissues were also stained for intrahepatic WHV core antigen (WHcAg) and WHsAg detection using immunohistochemical methods (46, 57). Specimens stained for cytoplasmic WHsAg were scored on a scale of 0 to 4 for determining the frequency of hepatocytes expressing this antigen (1 indicates staining of up to 1% of hepatocytes, 2 indicates staining of up to 2% of hepatocytes, 3 indicates staining of up to 5% of hepatocytes, and 4 indicates staining of 10% or more hepatocytes). A second aliquot of liver was placed immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until nucleic acid analyses were performed. Levels of hepatic WHV DNA and WHV RNA were measured quantitatively by Southern or Northern blot hybridization as previously described (27, 57).

Statistical analyses.

The antiviral effects of oral administration of 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF alone and in combination were analyzed by comparing the log-transformed serum WHV DNA values during drug treatment (weeks 1 to 48) and following the termination of drug treatment (weeks 49 to 60) with the respective pretreatment (week 0) and placebo control values. The antiviral effects induced by 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF alone and in combination were assessed further by comparing the mean serum WHsAg levels for log-transformed values, the mean hepatic WHV nucleic acid values, the mean percentages or scores of hepatocytes expressing WHV antigens, and the mean scores of portal and lobular hepatitis during and following drug treatment with the pretreatment and placebo control values. Statistical comparisons were performed using a Student's t test (two tailed), Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or Mann-Whitney U test (two tailed, exact value) with SPSS program 13.0 (SSPS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences with P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Serum WHV DNA.

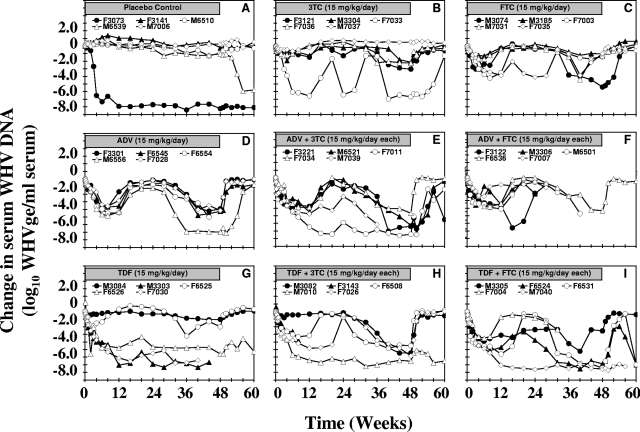

The results for serum WHV DNA of individual woodchucks from all treatment groups are shown in Fig. 1, and the mean serum WHV DNA values for the groups are shown in Fig. 2. No changes in serum WHV DNA levels were observed in four of five placebo-treated control woodchucks throughout the drug treatment period (Fig. 1A and 2A). One of these four woodchucks (woodchuck M6539), however, had a remarkable decrease in serum WHV DNA levels late, at week 54 of the study. In the fifth woodchuck of this group (woodchuck F3073), chronic WHV infection appeared to resolve spontaneously early on, as indicated by the stable reduction of serum WHV DNA levels from week 4 onward, with a parallel reduction in serum WHsAg and development of anti-WHs antibody. Overall, throughout the study, the mean serum WHV DNA values in this group were not significantly different from the mean pretreatment value (P > 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on serum WHV DNA levels in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (A), 3TC (B), FTC (C), ADV (D), ADV plus 3TC (E), ADV plus FTC (F), TDF (G), TDF plus 3TC (H), and TDF plus FTC (I). Horizontal bars indicate the 48-week treatment period. Log10 changes in serum WHV DNA levels from baseline at week 0 prior to drug administration for individual woodchucks in each treatment group are displayed. WHVge, WHV genomic equivalents (virion- or WHV DNA-containing virus particles).

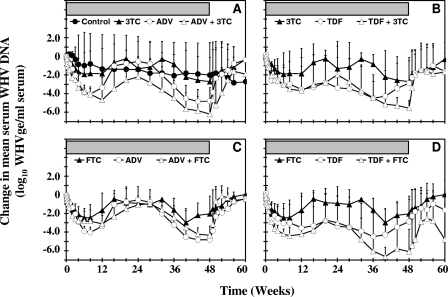

FIG. 2.

Comparison of antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on serum WHV DNA levels in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. (A) Monotherapy with ADV or 3TC and combination therapy with ADV and 3TC. The placebo control group is displayed for comparison. (B) Monotherapy with TDF or 3TC and combination therapy with TDF and 3TC. (C) Monotherapy with ADV or FTC and combination therapy with ADV and FTC. (D) Monotherapy with TDF or FTC and combination therapy with TDF and FTC. Horizontal bars indicate the 48-week treatment period. Mean log10 changes in serum WHV DNA levels from baseline at week 0 prior to drug administration for each treatment group are displayed. Vertical lines indicate standard deviations. Each group contained five woodchucks at the start of treatment. Differences in geometric mean serum WHV DNA concentrations from pretreatment values were significant for the following treatment groups and time points (P < 0.05): 3TC, days 1 to 5 and weeks 1 to 8; FTC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 12 and 28 to 52; ADV, days 1 to 5 and weeks 1 to 44; TDF, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 6 and 28 to 36; ADV plus 3TC, days 1 to 5 and weeks 1 to 36; ADV plus FTC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 24; TDF plus 3TC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 8; and TDF plus FTC, days 1 to 5 and weeks 1 to 32 of the study. Differences in geometric mean serum WHV DNA concentrations from those in the placebo control group were significant for the following treatment groups and time points (P < 0.05): 3TC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 2; FTC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 2; ADV, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 3; TDF, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 3; ADV plus 3TC, days 1 to 5 and weeks 1 to 3; ADV plus FTC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 3; TDF plus 3TC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 3; and TDF plus FTC, days 2 to 5 and weeks 1 to 3 of treatment. WHVge, WHV genomic equivalents (virion- or WHV DNA-containing virus particles).

Monotherapy with 3TC produced a gradual reduction in serum WHV DNA levels averaging 1.9 log10 genome equivalents/ml after the initial 12 weeks of treatment, with recrudescence to pretreatment levels shortly thereafter (Fig. 1B and 2A and B). In three woodchucks (woodchucks F3121, M3304, and F7036), a later and further reduction in serum WHV DNA levels of 4 to 5 log10 genome equivalents/ml was observed beginning at 36 weeks of treatment, which continued until the end of treatment. One woodchuck (woodchuck F7033) had a marked and sustained reduction in serum WHV DNA levels nearly throughout the study. Mean serum WHV DNA levels in woodchucks treated with 3TC were significantly reduced from the pretreatment level at days 1 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 8 (P < 0.05) and were significantly lower than those in the placebo control group at days 2 to 5 and at weeks 1 and 2 of treatment (P < 0.05). By the end of treatment at week 48, the serum WHV DNA level was reduced by an average of 2.7 log10 genome equivalents/ml from the pretreatment level. After drug withdrawal, recrudescence of viral replication was observed in all woodchucks treated with 3TC.

Monotherapy with FTC induced a more rapid decline in serum WHV DNA levels than did treatment with 3TC. Reductions in WHV DNA levels averaged 2.5 log10 genome equivalents/ml during the initial 6 to 8 weeks of treatment, with recrudescence in four of five woodchucks beginning at week 12 (Fig. 1C and 2C and D). Mean serum WHV DNA levels were significantly reduced compared with the pretreatment level at days 2 to 5, between weeks 1 and 12, and again between weeks 28 and 52 of the study (P < 0.05) and were significantly lower than those in the placebo control group at days 2 to 5 and at weeks 1 and 2 of treatment (P < 0.05). The timing of the antiviral response varied across individual woodchucks. By the end of treatment at week 48, serum WHV DNA levels were reduced by an average of 2.0 log10 genome equivalents/ml. Recrudescence of viral replication after treatment ended was immediate in all woodchucks.

Monotherapy with ADV resulted in a prompt reduction in serum WHV DNA levels, averaging 3.4 log10 genome equivalents/ml during the initial 12 weeks of treatment (Fig. 1D and 2A and C). The antiviral responses in this group showed little individual variation during this time period. This initial reduction in serum WHV DNA levels was followed by recrudescence in all woodchucks starting between weeks 12 and 16 of treatment and lasting until week 24. Serum WHV DNA levels became reduced again later between weeks 28 and 32 of treatment. Woodchuck F6554 was found dead during week 47 of treatment. The actual cause of death was not determined, but giant cell hepatopathy was present. By the end of treatment, the serum WHV DNA level was reduced by an average of 4.8 log10 genome equivalents/ml. After drug withdrawal, recrudescence of viral replication was observed immediately in three woodchucks and later, at week 52, in the fourth woodchuck (woodchuck M6556). Mean serum WHV DNA levels in this group were significantly reduced compared with the pretreatment level at days 1 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 44 of treatment (P < 0.05). Serum WHV DNA levels were also significantly less than those in the placebo control group at days 2 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 3 of treatment (P < 0.05).

Monotherapy with TDF produced a prompt decline in mean serum WHV DNA levels, averaging 3.6 log10 genome equivalents/ml after the initial 12 weeks of treatment, with a high degree of individual variation in the antiviral responses (Fig. 1G and 2B and D). Pronounced and sustained reductions in serum WHV DNA levels were observed in three woodchucks (woodchucks M3303, F6526, and F7030). A less robust antiviral response was observed in a fourth woodchuck (woodchuck F6525) during initial treatment, but by the end of the first 12 weeks, the serum WHV DNA level had returned to the pretreatment level, only to decline again at week 36. The fifth woodchuck (woodchuck M3084) did not respond to TDF. Two woodchucks (woodchucks F7030 and M3303) were euthanized at weeks 41 and 44, respectively, because of seizures that were recognized clinically as a preterminal sign of HCC. By the end of treatment, the serum WHV DNA level was reduced by an average of 2.9 log10 genome equivalents/ml. In one (woodchuck F6525) of two woodchucks surviving after drug withdrawal, there was an immediate recrudescence of viral replication, whereas in the second woodchuck (woodchuck F6526), the antiviral effect was sustained until the end of the study. Mean serum WHV DNA levels were significantly reduced compared with the mean pretreatment level at days 2 to 5, between weeks 1 and 6, and again between weeks 28 and 36 of treatment (P < 0.05). Serum WHV DNA levels were also significantly lower than those in the placebo control group at days 2 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 3 of treatment (P < 0.05).

Combination therapy with ADV and 3TC resulted in a prompt reduction in mean serum WHV DNA levels, with an average 4.7-log10 decrease after 12 weeks (Fig. 1E and 2A). The initial antiviral responses of this group showed little individual variation. Recrudescence of viral replication during treatment was then observed in four woodchucks (woodchucks F3221, M6521, F7034, and M7039) beginning at week 16. Serum WHV DNA levels in these four woodchucks decreased again after 36 weeks of treatment. Woodchuck M7039 was euthanized at week 36 because of signs of advanced HCC. A sustained reduction in serum WHV DNA levels was observed in the fifth woodchuck (woodchuck F7011). By the end of treatment, the mean serum WHV DNA level was reduced by an average of 6.2 log10 genome equivalents/ml. After drug withdrawal, recrudescence of viral replication was observed in three woodchucks starting between weeks 49 and 52 of the study (woodchuck M6521, F7011, and F7034) and was delayed slightly longer in the fourth surviving woodchuck (woodchuck F3221). Mean serum WHV DNA levels in this group were significantly reduced compared to the mean pretreatment level at days 1 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 36 of treatment (P < 0.05). Mean serum WHV DNA levels were also significantly lower than those in the placebo control group at days 1 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 3 of treatment (P < 0.05).

Combination therapy with ADV and FTC also resulted in a prompt reduction in mean serum WHV DNA levels, averaging 3.1 log10 genome equivalents/ml during the initial 12 weeks of treatment (Fig. 1F and 2C). Beginning at week 16, recrudescence of viral replication was observed in four of five woodchucks (woodchucks M3306, M6501, F6536, and F7007). One woodchuck (woodchuck M3306) was euthanized because of advanced HCC at week 22. Serum WHV DNA levels decreased again in the other three woodchucks (woodchucks M6501, F6536, and F7007) between weeks 24 and 28 and remained below pretreatment levels in two (woodchucks M6501 and F7007) until the time of death or euthanasia related to HCC. In the other woodchuck (woodchuck F6536), serum WHV DNA levels remained below the pretreatment level until drug treatment ended, followed by immediate recrudescence. The fifth woodchuck in this group (woodchuck F3122) had a more sustained antiviral response, with recrudescence of viral replication prior to death during week 24 of treatment. Death was sudden and was attributed to cecal torsion with infarction and peritonitis. Myocardial and skeletal muscle degeneration and necrosis and mild vacuolar hepatopathy were present. However, no prodromal signs suggestive of nucleoside-induced mitochondrial toxicity had been observed. By the end of treatment, the serum WHV DNA level in the single surviving woodchuck (woodchuck F6536) was reduced by 4.4 log10 genome equivalents/ml. Mean serum WHV DNA levels in this group were significantly reduced compared with the pretreatment level at days 2 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 24 of treatment (P < 0.05). Mean serum WHV DNA levels were also significantly lower than those in the placebo control group at days 2 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 3 of treatment (P < 0.05).

Combination therapy with TDF and 3TC resulted in a prompt reduction in serum WHV DNA levels in four of the woodchucks (woodchucks F3143, F6508, M7010, and F7026), but in the fifth woodchuck (woodchuck M3082), no initial antiviral response was observed (Fig. 1H and 2B). Woodchuck F3143 was found partially paralyzed during week 9 of treatment and was euthanized. After 12 weeks of treatment, the serum WHV DNA level was decreased by an average of 3.7 log10 genome equivalents/ml. The antiviral response of one woodchuck (woodchuck M7010) was sustained during treatment and following drug withdrawal. Two other woodchucks (woodchucks F6508 and F7026) showed recrudescence of viral replication starting at weeks 16 and 24 of treatment, respectively. Reduction in serum WHV DNA levels was observed again in both woodchucks between weeks 24 and 28, respectively. In the fifth woodchuck of this group (woodchuck M3082), serum WHV DNA levels started to decline at week 28 and decreased progressively until the end of treatment. By the end of treatment, serum WHV DNA levels were reduced on average by 5.6 log10 genome equivalents/ml. After drug withdrawal, recrudescence of viral replication was observed in three surviving woodchucks (woodchuck M3082, F6508, and F7026), while the antiviral effect was sustained in the fourth woodchuck (woodchuck M7010). Mean serum WHV DNA levels in this group were significantly reduced compared with the pretreatment level at days 2 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 8 of treatment (P < 0.05). Mean serum WHV DNA levels were also significantly lower than those in the placebo control group at days 2 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 3 of treatment (P < 0.05).

Combination therapy with TDF and FTC induced a prompt decline in serum WHV DNA levels, averaging 4.4 log10 genome equivalents/ml during the initial 8 weeks of treatment, with individual variation in the antiviral response (Fig. 1I and 2D). This was followed by the recrudescence of viral replication in four woodchucks (woodchucks M3305, F6524, F6531, and F7004). The fifth woodchuck (woodchuck M7040) had a sustained reduction in serum WHV DNA levels lasting until the time of death during week 59. Death was attributed to the rupture of an aortic aneurysm, atherosclerosis, and glomerulopathy, all consistent with the presence of hypertension. Advanced HCC was also present. In the other four woodchucks, serum WHV DNA levels started to decrease again between weeks 24 and 36. Woodchuck F7004 was euthanized during week 32 of treatment because of signs of advanced HCC. WHV DNA levels remained below pretreatment levels until the end of treatment in the three surviving woodchucks (woodchucks M3305, F6524, and F6531). By the end of treatment, the serum WHV DNA level was reduced by an average of 6.1 log10 genome equivalents/ml. After drug withdrawal, recrudescence of viral replication was observed in three woodchucks (woodchucks M3305, F6524, and F6531), but at the end of the study, serum WHV DNA levels in two woodchucks (woodchucks F6524 and F6531) again decreased remarkably. Mean serum WHV DNA levels in this group were significantly reduced compared with the pretreatment level at days 1 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 32 of treatment (P < 0.05). Mean serum WHV DNA levels were also significantly less than those in the placebo control group at days 2 to 5 and between weeks 1 and 3 of treatment (P < 0.05).

Serum WHsAg.

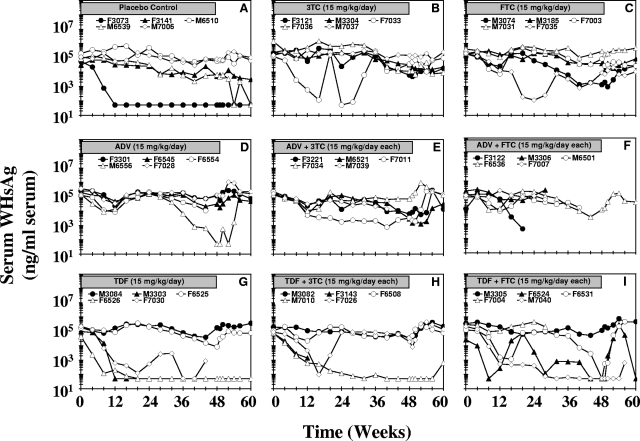

Remarkable reductions were observed in the serum WHsAg concentrations of individual woodchucks across all groups (Fig. 3). One woodchuck each in the groups receiving ADV (woodchuck M6556), ADV plus 3TC (woodchuck F7011), and ADV plus FTC (woodchuck F3122) and two woodchucks each in the groups receiving 3TC (woodchucks F3121 and F7033) and FTC (woodchucks M3074 and F7035) had pronounced reductions in serum WHsAg concentrations during the 48 weeks of treatment. Three woodchucks each in the groups treated with TDF (woodchucks M3303, F6526, and F7030), TDF plus 3TC (woodchucks F3143, M7010, and F7026), and TDF plus FTC (woodchucks F6524, F6531, and M7040) had pronounced and sometimes sustained reductions in serum WHsAg levels during treatment. In most drug-treated woodchucks having reductions in serum WHsAg levels, the levels returned to the pretreatment level immediately after drug withdrawal, but reductions were sustained in one woodchuck each in the groups receiving TDF (woodchuck F6526), TDF plus 3TC (woodchuck M7010), and TDF plus FTC (woodchuck M7040) (until the time of death during week 56). Two woodchucks from the placebo-treated control group (woodchucks F3073 and M6539) had reductions in serum WHsAg levels, but the decline was sustained only in one control woodchuck in which WHV infection spontaneously resolved (woodchuck F3073). Overall, although remarkable and sometimes sustained declines in serum WHsAg levels of individual woodchucks were observed, the mean serum WHsAg levels in the drug-treated groups were not significantly different from those in the placebo control group throughout the study (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Comparison of serum WHV DNA concentrations with serum WHsAg levels showed a direct relationship between the magnitudes of the reductions in serum viral DNA levels and serum antigenemia in individual woodchucks (Fig. 1 and 3).

FIG. 3.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on serum WHsAg concentrations in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (A), 3TC (B), FTC (C), ADV (D), ADV plus 3TC (E), ADV plus FTC (F), TDF (G), TDF plus 3TC (H), and TDF plus FTC (I). Horizontal bars indicate the 48-week treatment period. Serum WHsAg concentrations for individual woodchucks in each treatment group are displayed.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of antiviral effect of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on concentrations of serum WHsAg, hepatic WHV DNA RI, and WHV RNA; hepatic expression of WHcAg and cytoplasmic WHsAg; and portal and lobular hepatitis in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks at selected time points during the study

| Treatmenta | Study period (time [wk]) | No. of animals | Geometric mean serum WHsAg concn ± SD (log10 ng/ml) | Mean hepatic WHV DNA RI concn ± SD (pg/μg total cell DNA) | Mean hepatic WHV RNA concn ± SD (pg/μg total cell RNA) | % Mean WHcAg-positive hepatocytes ± SD | Mean score ± SDd

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHsAg-positive hepatocytes | Portal hepatitis | Lobular hepatitis | |||||||

| Placebo | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 1733 ± 327 | 54 ± 6 | 57 ± 31 | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 1495 ± 890 | 46 ± 25 | 55 ± 32 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 5 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 1132 ± 738 | 33 ± 21 | 41 ± 25 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 5 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 995 ± 736 | 34 ± 20 | 35 ± 27 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of study (60) | 5 | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 979 ± 1124 | 27 ± 28 | 26 ± 29 | 2 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| 3TC | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 1439 ± 295 | 51 ± 3 | 51 ± 15 | 2 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | 982 ± 548 | 39 ± 21 | 39 ± 36 | 1 ± 1b | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 5 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 1133 ± 443 | 47 ± 5 | 59 ± 9 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 5 | 4.4 ± 0.5b | 413 ± 349b | 33 ± 21 | 36 ± 26 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of study (60) | 5 | 4.6 ± 0.6b | 1063 ± 606 | 46 ± 14 | 48 ± 32 | 3 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| FTC | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 1485 ± 198 | 53 ± 5 | 48 ± 21 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.5 ± 0.6b | 845 ± 655 | 42 ± 17 | 47 ± 28 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 644 ± 355b | 43 ± 10 | 63 ± 18 | 4 ± 1 | 1 ± 0b | 1 ± 0 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 5 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 428 ± 265b | 35 ± 14b | 40 ± 23 | 4 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of study (60) | 5 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 1239 ± 288 | 48 ± 7 | 64 ± 9 | 4 ± 0 | 1 ± 1b | 1 ± 1 | |

| ADV | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 1657 ± 332 | 48 ± 4 | 50 ± 14 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.3 ± 0.3b | 330 ± 238b,c | 33 ± 14b | 21 ± 16b | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 324 ± 217b,c | 34 ± 8b | 45 ± 27 | 3 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 4 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 151 ± 140b | 24 ± 11b | 13 ± 13b | 2 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | |

| End of study (60) | 4 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 1147 ± 371 | 46 ± 3 | 48 ± 6 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | |

| TDF | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 1595 ± 369 | 48 ± 10 | 61 ± 11 | 1 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 3.4 ± 1.6b | 870 ± 1165 | 30 ± 23 | 30 ± 41 | 0 ± 0b | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 5 | 2.9 ± 1.7b | 443 ± 587b | 25 ± 25 | 20 ± 31b | 1 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 3 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 704 ± 647b | 31 ± 24 | 26 ± 33 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of study (60) | 3 | 4.0 ± 2.1 | 1374 ± 1196 | 34 ± 29 | 39 ± 34 | 2 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | |

| ADV + 3TC | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 1443 ± 457 | 47 ± 9 | 58 ± 21 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.1 ± 0.3b | 240 ± 232b,c | 25 ± 12b | 12 ± 10b,c | 1 ± 1b | 0 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.4 ± 0.6b | 346 ± 312b | 27 ± 10b | 47 ± 31 | 2 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 4 | 3.9 ± 0.7b | 57 ± 43b | 19 ± 12b | 12 ± 18b | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | |

| End of study (60) | 4 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 831 ± 232b,c | 32 ± 12 | 36 ± 27 | 1 ± 1b | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| ADV + FTC | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 1404 ± 285 | 46 ± 7 | 48 ± 21 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0c |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 885 ± 470 | 33 ± 7b | 51 ± 21 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 2 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 376 | 39 | 26 | 4 | 1 | 0 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 1 | 4.0 | 313 | 22 | 51 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| End of study (60) | 1 | 4.5 | 960 | 24 | 49 | 4 | 1 | 0 | |

| TDF + 3TC | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 1703 ± 310 | 53 ± 5 | 60 ± 14 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 4 | 3.8 ± 0.9b | 369 ± 485b | 32 ± 7b | 28 ± 31 | 1 ± 1b | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 4 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 188 ± 160b,c | 31 ± 18b | 36 ± 32 | 2 ± 2 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 4 | 3.8 ± 1.4 | 95 ± 67b,c | 23 ± 14b | 19 ± 31 | 2 ± 2 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 0c | |

| End of study (60) | 4 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 1115 ± 981 | 28 ± 21b | 44 ± 33 | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| TDF + FTC | Pretreatment (0) | 5 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 1811 ± 282 | 55 ± 6 | 57 ± 25 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 1 |

| 12 wk of treatment | 5 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | 497 ± 562b | 22 ± 12b | 21 ± 24b | 1 ± 0b | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 36 wk of treatment | 4 | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 125 ± 124b,c | 17 ± 13b | 22 ± 31 | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of treatment (48) | 4 | 2.5 ± 1.7b | 136 ± 195b | 15 ± 13b | 4 ± 7b | 2 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | |

| End of study (60) | 4 | 3.7 ± 2.8 | 1077 ± 729 | 42 ± 3b | 22 ± 38 | 0 ± 1b | 1 ± 1b | 0 ± 1 | |

Each group contained five woodchucks at the start of treatment. Values are means ± standard deviations.

Difference from the pretreatment value was statistically significant (P< 0.05).

Difference from the placebo control group was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Hepatic staining for cytoplasmic WHsAg was scored on a scale of 0 to 4 (1 is staining of up to 1% of hepatocytes, 2 is staining of up to 2% of hepatocytes, 3 is staining of up to 5% of hepatocytes, and 4 is staining of 10% or more hepatocytes). According to their severity, portal hepatitis and lobular hepatitis were graded on a scale of 0 to 4 (representing absent lesion to the most severe lesion, respectively).

Serum anti-WHc and anti-WHs antibodies.

No meaningful significant differences in serum anti-WHc antibody levels were evident between the pretreatment determinations and those during or after treatment in any of the treatment groups or between the placebo- and drug-treated groups at any time point (data not shown). None of the drug-treated woodchucks developed anti-WHs antibody except for one woodchuck from the group receiving ADV plus FTC (woodchuck F6536) that had low-level anti-WHs antibody throughout the study. In fact, a remarkable anti-WHs antibody response was detected only in one woodchuck from the placebo-treated control group (F3073) in which WHV infection spontaneously resolved (data not shown). The observations of anti-WHs are important because they indicate that the antiviral effects observed in drug-treated groups were not related to the spontaneous resolution of WHV infection.

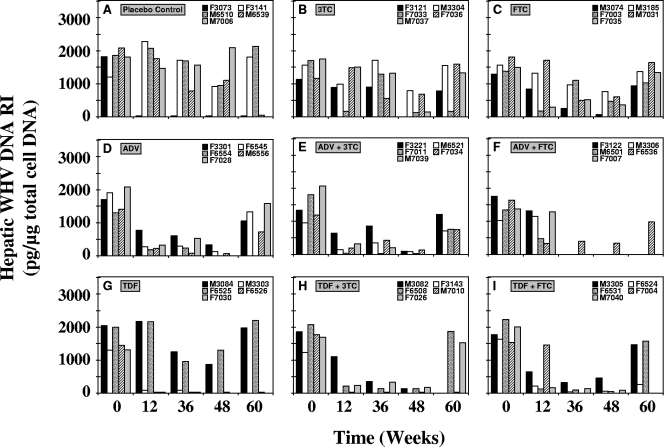

Hepatic WHV DNA RI.

Remarkable reductions in the hepatic concentrations of WHV DNA replicative intermediates (RI) of individual woodchucks were observed across all groups (Fig. 4). Hepatic WHV DNA RI concentrations returned to pretreatment levels in most woodchucks immediately or shortly after the end of treatment at week 48, but the reductions were sustained in one woodchuck from each of the groups receiving 3TC (woodchuck F7033), TDF (woodchuck F6526), TDF plus 3TC (woodchuck M7010), and TDF plus FTC (woodchuck F6524). Overall, mean hepatic WHV DNA RI levels were significantly reduced compared with the mean pretreatment level (P < 0.05) in several liver samples obtained through the end of treatment (weeks 12, 36, and 48) and follow-up (week 60) in the groups receiving 3TC (week 48), FTC (weeks 36 and 48), ADV (weeks 12, 36, and 48), TDF (weeks 36 and 48), ADV plus 3TC (weeks 12, 36, 48, and 60), TDF plus 3TC (weeks 12, 36, and 48), and TDF plus FTC (weeks 12, 36, and 48) (Table 1). Furthermore, hepatic WHV DNA RI levels were significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the groups receiving ADV (weeks 12 and 36), ADV plus 3TC (weeks 12 and 48), TDF plus 3TC (weeks 36 and 48), and TDF plus FTC (week 36) than those in the placebo control group (Table 1). After 12 weeks of treatment, combination therapy with ADV and 3TC produced the greatest antiviral effect on hepatic WHV DNA RI, with a 6.0-fold reduction from the pretreatment level. This was followed in rank order by monotherapy with ADV, combination therapy with TDF and 3TC, combination therapy with TDF and FTC, monotherapy with TDF or FTC, combination therapy with ADV and FTC, and monotherapy with 3TC. After 48 weeks of treatment, the combination of ADV and 3TC had the most sustained effect, with a 25.2-fold reduction in hepatic WHV DNA RI concentrations from the pretreatment level. This was followed in rank order by combination therapy with TDF and 3TC, combination therapy with TDF and FTC, monotherapy with ADV, monotherapy with 3TC or FTC, and monotherapy with TDF. At the end of treatment, the single survivor of combination therapy with ADV and FTC had a 4.5-fold reduction in hepatic WHV DNA RI concentrations from the pretreatment level.

FIG. 4.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on hepatic WHV replication in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchuck M7006 at week 60) (A), 3TC (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchuck F3121 at week 48) (B), FTC (C) ADV (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchuck F6554 at weeks 48 and 60 and from woodchuck F7028 at week 48) (D), ADV plus 3TC (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchuck M7039 at weeks 48 and 60) (E), ADV plus FTC (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchucks F3122, M3306, M6501, and F7007 at weeks 36, 48, and 60) (F), TDF (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchucks M3003 and F7030 at weeks 48 and 60) (G), TDF plus 3TC (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchuck F3143 at weeks 12, 36, 48, and 60 and from woodchuck M3082 at week 60) (H), and TDF plus FTC (hepatic tissue was not available from woodchuck F7004 at weeks 36, 48, and 60 and from woodchuck M7040 at week 60) (I). Levels of hepatic cellular DNA were quantified by hybridization to a woodchuck-specific β-actin gene probe by the Southern blot hybridization technique.

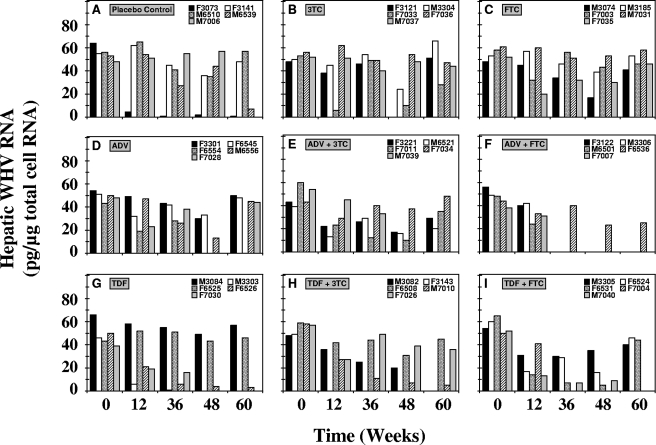

Hepatic WHV RNA.

Pronounced reductions were also observed in the levels of hepatic WHV RNA of individual woodchucks from the various treatment groups during the 48 weeks of treatment (Fig. 5). Hepatic WHV RNA levels returned to pretreatment levels in most woodchucks immediately after the end of treatment at week 48, but reductions were sustained in one woodchuck each in the groups receiving TDF (woodchuck F6526), TDF plus 3TC (woodchuck M7010), and TDF plus FTC (woodchuck M7040). Overall, although remarkable declines in hepatic WHV RNA levels of individual woodchucks were observed, the mean WHV RNA levels in the drug-treated groups were not significantly different from those in the placebo control group throughout the study (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

FIG. 5.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on hepatic WHV RNA levels in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (A), 3TC (B), FTC (C), ADV (D), ADV plus 3TC (E), ADV plus FTC (F), TDF (G), TDF plus 3TC (H), and TDF plus FTC (I). See the legend to Fig. 4 for data on the availability of hepatic tissue of individual woodchucks from the experimental groups. Levels of hepatic cellular RNA were quantified by hybridization to a woodchuck-specific 18S gene probe by the Northern blot hybridization technique.

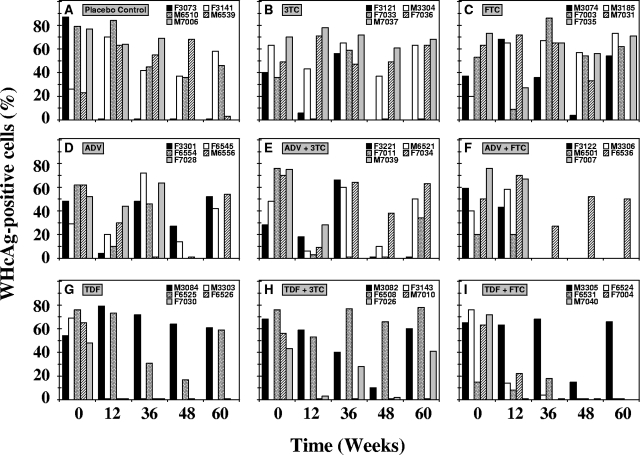

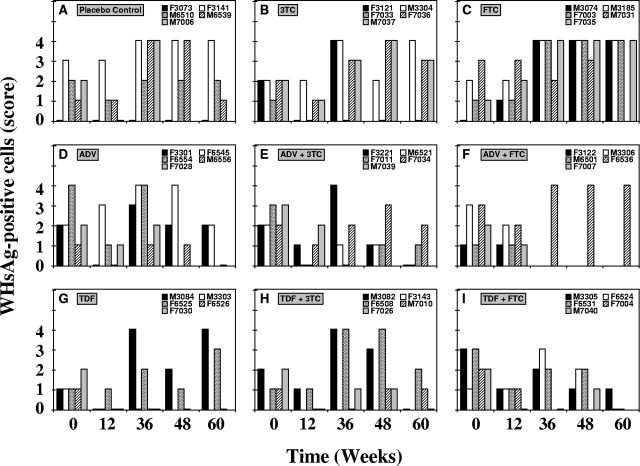

Hepatic WHcAg and WHsAg.

Transient reductions in the levels of expression of WHcAg and of cytoplasmic WHsAg in hepatocytes were observed in individual woodchucks across all groups (Fig. 6 and 7). Individual variation was evident, with occasional differences between group mean values (Table 1). The percentages of hepatocytes staining positive for WHcAg were significantly reduced compared with that at pretreatment (P < 0.05) in the groups receiving ADV (weeks 12 and 48), TDF (week 36), ADV plus 3TC (weeks 12 and 48), and TDF plus FTC (weeks 12 and 48). In the group treated with ADV plus 3TC, the percentage of hepatocytes positive for WHcAg was significantly lower than that in the placebo control at week 12 (P < 0.05). Declines in the percentages of hepatocytes staining positive for WHsAg of individual woodchucks were also observed, but the declines in the drug-treated groups were not significantly different from the changes in the placebo control group throughout the study (P > 0.05).

FIG. 6.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on hepatic expression of WHcAg in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (A), 3TC (B), FTC (C), ADV (D), ADV plus 3TC (E), ADV plus FTC (F), TDF (G), TDF plus 3TC (H), and TDF plus FTC (I). See the legend to Fig. 4 for data on the availability of hepatic tissue of individual woodchucks from the experimental groups.

FIG. 7.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on hepatic expression of cytoplasmic WHsAg in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (A), 3TC (B), FTC (C), ADV (D), ADV plus 3TC (E), ADV plus FTC (F), TDF (G), TDF plus 3TC (H), and TDF plus FTC (I). See the legend to Fig. 4 for data on the availability of hepatic tissue from individual woodchucks from the experimental groups. According to the number of hepatocytes, staining was scored on a scale of 0 to 4 (1 is staining of up to 1% of hepatocytes, 2 is staining of up to 2% of hepatocytes, 3 is staining of up to 5% of hepatocytes, and 4 is staining of 10% or more hepatocytes).

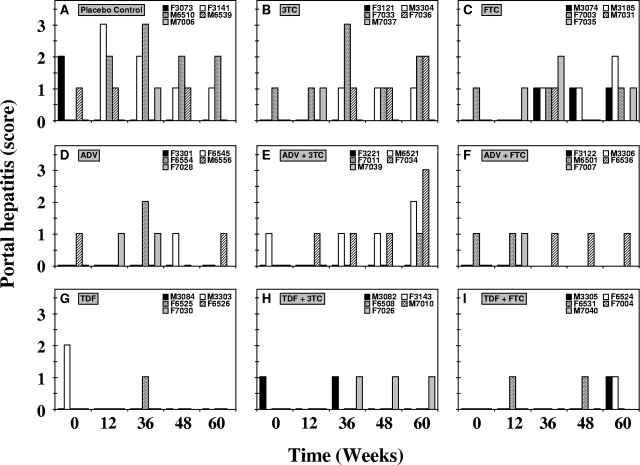

Histopathology.

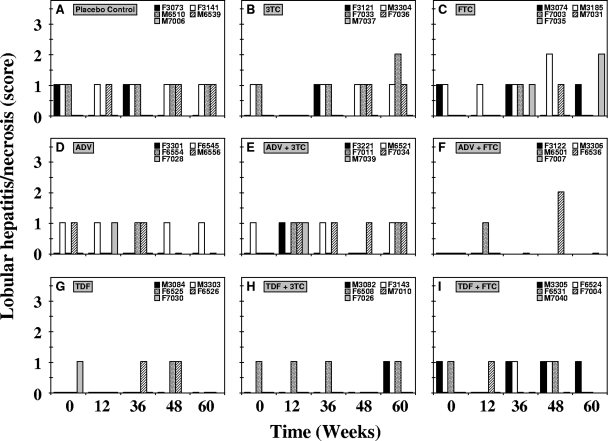

Portal hepatitis and lobular hepatitis were either absent or mild in all woodchucks before the start of treatment (Fig. 8 and 9). Transient reductions in portal and lobular hepatitis were observed in individual woodchucks from the various treatment groups, but individual variation was evident, with occasional differences between group mean values (Table 1). At week 12 of treatment, portal hepatitis was reduced transiently in the groups receiving TDF and TDF plus 3TC. A transient reduction in portal hepatitis levels was also observed in the group treated with TDF plus FTC at week 36 of treatment. By the end of treatment at week 48, portal hepatitis was reduced in the group treated with TDF, and this reduction was sustained until the end of the study at week 60. Reductions from pretreatment levels and differences between the drug-treated and placebo control groups in portal hepatitis, however, were not significant (P < 0.05). Transient reductions in levels of lobular hepatitis were observed for the groups receiving 3TC and TDF at week 12 of treatment. At week 36 of treatment, the level of lobular hepatitis was transiently reduced in the single surviving woodchuck from the group treated with ADF plus FTC. By the end of treatment at week 48, lobular hepatitis was transiently reduced in the group treated with TDF plus 3TC. By the end of the study at week 60, lobular hepatitis was again reduced in the group treated with TDF and in the single surviving woodchuck from the group treated with ADF plus FTC. The reduction in lobular hepatitis observed in the group receiving TDF plus 3TC was significantly greater than that in the placebo control at week 48 (P < 0.05). Overall, portal and lobular hepatitis remained mild in woodchucks across all experimental groups at the end of the study.

FIG. 8.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on portal hepatitis in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (A), 3TC (B), FTC (C), ADV (D), ADV plus 3TC (E), ADV plus FTC (F), TDF (G), TDF plus 3TC (H), and TDF plus FTC (I). See the legend to Fig. 4 for data on the availability of hepatic tissue from individual woodchucks from the experimental groups. According to their severities, the specific lesions were graded on a scale of 0 to 4 (representing an absent lesion to the most severe lesion, respectively).

FIG. 9.

Antiviral effects of oral 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF administration alone and in combination on lobular hepatitis in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment groups were as follows: placebo (A), 3TC (B), FTC (C), ADV (D), ADV plus 3TC (E), ADV plus FTC (F), TDF (G), TDF plus 3TC (H), and TDF plus FTC (I). See the legend to Fig. 4 for data on the availability of hepatic tissue from individual woodchucks from the experimental groups. According to their severity, the specific lesions were graded on a scale of 0 to 4 (representing an absent lesion to the most severe lesion, respectively).

Toxicity.

No clinical signs of toxicity were observed in woodchucks treated with 3TC, FTC, ADV, or TDF alone or in combination. Changes in body weights of woodchucks in the drug-treated groups were similar to those of placebo-treated control woodchucks. The hematological and biochemical profiles of woodchucks in the drug-treated groups were also similar to those of placebo-treated controls during treatment and after drug withdrawal for most parameters (data not shown). One or more woodchucks in each experimental group had increases in serum SDH, GGT, ALT, AST, and ALP activities during the period of drug treatment (data not shown). Increases in SDH activity between weeks 4 and 24 of treatment in individual woodchucks were almost always associated with proportional elevations in ALT activity, suggesting increased hepatitic activity. Increases in SDH activity between weeks 28 and 48 of treatment and after drug withdrawal were almost always associated with proportional increases in GGT, ALT, AST, and/or ALP activities, which suggested the development of HCC.

One woodchuck each from the groups receiving ADV plus FTC (woodchuck F3122), ADV (woodchuck F6554), and TDF plus FTC (woodchuck M7040) died unexpectedly during weeks 24, 47, and 59 of the study, respectively, but the deaths were not attributed to drug treatment. One woodchuck treated with TDF plus 3TC (woodchuck F3143) was discovered partially paralyzed during week 9 of treatment and was euthanized. Seven other woodchucks were euthanized or found dead during the period of drug treatment because of seizures that were recognized clinically as a preterminal sign of HCC. All seven of these woodchucks had developed pronounced elevations in serum GGT activity, and HCC was evident by ultrasound examination. Three of these seven woodchucks from the group receiving ADV plus FTC (woodchuck M3306, F7007, and M6501) were euthanized or found dead during weeks 22, 29, and 41 of treatment, respectively; two other woodchucks that had received TDF (woodchuck F7030 and M3303) were euthanized during weeks 41 and 44 of treatment, respectively; one woodchuck each from the groups receiving TDF plus FTC (woodchuck F7004) and ADV plus 3TC (woodchuck M7039) was euthanized at weeks 32 and 36 of treatment, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this placebo-controlled study, the antiviral activities of oral dosing with 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF alone or in combination were assessed against WHV in chronically infected woodchucks. In the woodchuck model of chronic HBV infection, the suppression of WHV replication in serum and liver in vivo was significantly greater in woodchucks treated with combination therapy of ADV and 3TC or TDF and FTC than in placebo-treated control animals, and no evidence of toxicity was observed during the 48-week period of daily oral administration.

During the initial 12 weeks of treatment, the combination of ADV and 3TC produced the greatest antiviral response, reducing serum WHV viremia from the pretreatment level by 4.7 log10 genome equivalents/ml. This was followed in rank order by TDF plus FTC (4.2 log10 genome equivalents/ml), TDF plus 3TC (3.7 log10 genome equivalents/ml), TDF alone (3.6 log10 genome equivalents/ml), ADV alone (3.4 log10 genome equivalents/ml), ADV plus FTC (3.1 log10 genome equivalents/ml), 3TC alone (1.9 log10 genome equivalents/ml), and FTC alone (1.7 log10 genome equivalents/ml). After 48 weeks of treatment, the combination of ADV plus 3TC or of TDF plus FTC produced the most sustained antiviral response, reducing serum viremia levels from the pretreatment level by 6.2 and 6.1 log10 genome equivalents/ml, respectively. This was followed by TDF plus 3TC (5.6 log10 genome equivalents/ml), ADV alone (4.8 log10 genome equivalents/ml), ADV plus FTC (one survivor) (4.4 log10 genome equivalents/ml), TDF alone (2.9 log10 genome equivalents/ml), 3TC alone (2.7 log10 genome equivalents/ml), and FTC alone (2.0 log10 genome equivalents/ml).

In general, the antiviral responses to the drugs and drug combinations in the present study varied across individual woodchucks, with the exception that minimal variation was noted for monotherapy with ADV. Various degrees of recrudescence of viral replication were observed in all drug-treated groups from 12 to 24 weeks, with a progressive reduction in serum viremia during the remainder of drug treatment. Recrudescence of viral replication after drug withdrawal was observed in most woodchucks. Woodchucks with pronounced and sustained reductions in serum viremia had the most pronounced declines in serum WHs antigenemia, hepatic WHV DNA RI and WHV RNA, and expression of viral antigens in liver. Treatment of woodchucks for 48 weeks did not elicit detectable antibodies against WHsAg in any of the drug-treated groups.

The generally robust antiviral responses observed during the initial 12 weeks in the groups of woodchucks treated with ADV or TDF alone or in combination with 3TC and FTC were followed by a recrudescence of WHV replication, which characteristically peaked after 24 weeks. Beginning at 30 weeks, levels of serum viremia in these groups decreased progressively until the end of the 48-week drug treatment period. The reason for the transient viral recrudescence is not known and has not been observed previously in long-term antiviral studies in woodchucks treated with 3TC, entecavir, or 1-(2-fluoro-5-methyl-β-l-arabinofuranosyl)uracil (clevudine) (8, 24, 36, 41, 55, 71). Partial sequencing of the WHV polymerase gene at week 24 of treatment indicated that recrudescence of viral replication was not related to the development of drug-resistant mutations within the B domain (data not shown). This finding is consistent with the observation that recrudescence of viral replication was transient and that pronounced reductions in serum viremia were then observed during the remainder of drug treatment.

Laboratory woodchucks, like their counterparts that live in the native habitat, have a rigorous endogenous circannual metabolic and reproductive rhythm. Food intake and metabolic rate are significantly reduced in the laboratory woodchuck from August until December, when increased metabolism and increased reproductive activity begin. Following the completion of the breeding season in March and April, food intake and metabolic rate increase significantly, and this is associated with a significant increase in body weight, primarily in the form of body fat. Food intake then decreases significantly beginning in July and August, and the annual cycle is repeated (9-11). Drug treatment in this study was initiated in January, and the height of recrudescence of serum WHV DNA was observed after 24 weeks, during the month of June, when food intake and body weight gain would both be maximal. The role of circannual metabolic and hormonal changes in determining the observed differences in the antiviral response is not known. It can only be speculated that the conversion of antiviral drugs to their active metabolites might have been influenced by season or the age of the experimental woodchucks. Blood levels of drug may also have varied during treatment because of changes either in intestinal absorption or in the rate of drug clearance. However, seasonal changes in the antiviral response independent of drug-resistant mutations have not been reported previously in long-term antiviral studies of woodchucks (8, 24, 36, 41, 55, 71).

The present results on antiviral effects are consistent with those from long-term antiviral studies of 3TC and ADV in woodchucks and of 3TC, FTC, ADV, or TDF on duck HBV and HBV in transiently or stably transfected cells and primary duck hepatocytes (14, 15, 17, 24, 26, 36, 52, 55, 67-69, 71).

The magnitude of the reduction in serum WHV viremia levels after 12 or 48 weeks of treatment with 3TC, FTC, ADV, or TDF and the time to viral recrudescence following drug withdrawal observed in this study were similar to those previously reported for some antiviral drugs after long-term administration to chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Treatment with 3TC for 24 weeks reduced serum WHV DNA levels by 1.5 log10 genome equivalents/ml, and WHV DNA levels returned to pretreatment levels within 1 or 2 weeks (26). Treatment with alpha interferon for 24 weeks reduced serum WHV viremia levels by 2.2 log10 genome equivalents/ml. WHV DNA levels returned to pretreatment levels in 1 to 2 weeks in the majority of woodchucks but were extended by 8 to 12 weeks in one woodchuck (26). Treatment with ADV for 12 weeks reduced serum WHV viremia levels by 2.5 log10 genome equivalents/ml, and WHV DNA returned to pretreatment levels within 6 weeks following drug withdrawal (14).

Treatment of chronic WHV carrier woodchucks with other antiviral drugs, however, induced greater antiviral effects on serum WHV viremia after long-term treatment than were observed in this study. Daily treatment with entecavir for 8 weeks and then weekly treatment for 14 or 36 months reduced serum WHV DNA levels by 5 to 8 log10 genome equivalents/ml (8). Treatment with 1-(2-fluoro-5-methyl-β-l-arabinofuranosyl)uracil (clevudine) for 32 weeks reduced serum WHV viremia levels by more than 8 log10 genome equivalents/ml in most woodchucks (28, 41). Recrudescence of viral replication was not observed until 8 weeks after drug withdrawal at the earliest in a few woodchucks, and the antiviral effect was sustained much longer in the majority of drug-treated woodchucks (i.e., through the end of the study).

A significant percentage of patients infected with HIV are coinfected with HBV and are at risk of developing HBV-associated liver diseases. Many patients coinfected with HIV and HBV have received 3TC as part of their combination therapy for HIV. Antiviral activity against HBV in such patients is characteristically transient because of the development of 3TC resistance (6, 18, 21, 60). In several recent studies, HIV patients with 3TC-resistant HBV infection have been treated with TDF or ADV, and a significant inhibition of HBV replication was demonstrated (1, 5, 7, 18, 43, 45, 47, 49-51). A combination of TDF and FTC has been used to treat patients coinfected with HIV and HBV, and robust anti-HBV responses were observed with the drug combination, which was reversed upon withdrawal of the combination (44).

Combination antiviral therapy is currently the standard of care for patients with HIV infection. Hypothetical advantages of combination therapy for HBV infection include the prevention or delay in the development of drug-resistant viral mutations and possible synergistic or additive antiviral drug interactions. Possible disadvantages include negative antiviral drug interactions and enhanced drug toxicity (33). During treatment of chronic WHV carrier woodchucks, monotherapy with either 3TC or FTC was modest and inferior to monotherapy with either ADV or TDF. At the end of the 48-week period of treatment, the combination of 3TC with either ADV or TDF was better than ADF or TDF monotherapy. Similarly, FTC combined with TDF was better than TDF at the end of treatment. However, the combination of ADV and FTC was not superior to ADV monotherapy. It was not possible to assess the inhibitory effect of drug combinations on the development of drug-resistant mutants because no such mutants had been detected at the end of the 48-week period of drug treatment in the monotherapy groups (data not shown). No negative drug interactions were observed in groups that received combinations of drugs. The durability of the antiviral response was not increased by combination therapy because levels of recrudescence of viremia after drug treatment ended were similar in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups.

There is increasing interest in the clinical use of drug combinations for the treatment of chronic HBV infection (33, 42). In HBV-infected patients, the effect of ADV combined with 3TC on viral load was no greater than that associated with ADV monotherapy initially, but after 2 years, the viral load of those receiving the drug combination was lower than that of the ADV monotherapy group, and rates of 3TC resistance were significantly lower in the combination group (53). TDF monotherapy has been shown to be safe and highly effective in HBV-infected patients for whom ADV therapy had failed (54).

The results of the present study of woodchucks indicate that stronger antiviral effects were observed with drug combinations than with monotherapies after 48 weeks of treatment. At the doses used, treatment with ADV in combination with 3TC or treatment with TDF in combination with FTC produced sustained antiviral responses and led to significant reductions in the concentrations of serum WHV DNA, hepatic WHV DNA RI, and hepatic WHV RNA and the hepatic expression of WHcAg and WHsAg in the woodchuck model of chronic HBV infection. A significant suppression of viral replication was also observed with TDF in combination with 3TC. Forty-eight weeks of therapy with 3TC, FTC, ADV, and TDF alone or in combination at oral doses of 15 mg/kg per day for each drug were well tolerated in WHV-infected woodchucks and produced no physical, biochemical, or hematological evidence of toxicity. The antiviral activities and the apparently favorable safety profile observed in woodchucks with drug doses comparable to or higher than those used in humans support the continued clinical development of combination treatments with ADV or TDF for the long-term treatment of chronic HBV infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by contract N01-AI-05399 (College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

We gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance of Mary Ascenzi, Betty Baldwin, Lou Ann Graham, Erin Graham, David Dietterich, and Chris Bellezza (Cornell University).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akyildiz, M., F. Gunsar, G. Ersoz, Z. Karasu, T. Ilter, Y. Batur, and U. Akarca. 2007. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine for three months in patients with lamivudine resistant compensated chronic hepatitis B. Dig. Dis. Sci. 52:3444-3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus, P., R. Vaughan, S. Xiong, H. Yang, W. Delaney, C. Gibbs, C. Brosgart, D. Colledge, R. Edwards, A. Ayres, A. Bartholomeusz, and S. Locarnini. 2003. Resistance to adefovir dipivoxil therapy associated with the selection of a novel mutation in the HBV polymerase. Gastroenterology 125:292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benhamou, Y., M. Bochet, V. Thibault, V. Calvez, M. H. Fievet, P. Vig, C. S. Gibbs, C. Brosgart, J. Fry, H. Namini, C. Katlama, and T. Poynard. 2001. Safety and efficacy of adefovir dipivoxil in patients co-infected with HIV-1 and lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus: an open-label pilot study. Lancet 358:718-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benhamou, Y., V. Thibault, P. Vig, V. Calvez, A. G. Marcelin, M. H. Fievet, G. Currie, C. G. Chang, L. Biao, S. Xiong, C. Brosgart, and T. Poynard. 2006. Safety and efficacy of adefovir dipivoxil in patients infected with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B and HIV-1. J. Hepatol. 44:62-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benhamou, Y., R. Tubiana, and V. Thibault. 2003. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in patients with HIV and lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:177-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessesen, M., D. Ives, L. Condreay, S. Lawrence, and K. E. Sherman. 1999. Chronic active hepatitis B exacerbations in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients following development of resistance to or withdrawal of lamivudine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:1032-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruno, R., P. Sacchi, C. Zocchetti, V. Ciappina, M. Puoti, and G. Filice. 2003. Rapid hepatitis B virus-DNA decay in co-infected HIV-hepatitis B virus ‘e-minus’ patients with YMDD mutations after 4 weeks of tenofovir therapy. AIDS 17:783-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colonno, R. J., E. V. Genovesi, I. Medina, L. Lamb, S. K. Durham, M. L. Huang, L. Corey, M. Littlejohn, S. Locarnini, B. C. Tennant, B. Rose, and J. M. Clark. 2001. Long-term entecavir treatment results in sustained antiviral efficacy and prolonged life span in the woodchuck model of chronic hepatitis infection. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1236-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Concannon, P., K. Levac, R. Rawson, B. Tennant, and A. Bensadoun. 2001. Seasonal changes in serum leptin, food intake, and body weight in photoentrained woodchucks. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 281:R951-R959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Concannon, P., P. Roberts, B. Baldwin, and B. Tennant. 1997. Long-term entrainment of circannual reproductive and metabolic cycles by Northern and Southern Hemisphere photoperiods in woodchucks (Marmota monax). Biol. Reprod. 57:1008-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Concannon, P. W., V. D. Castracane, R. E. Rawson, and B. C. Tennant. 1999. Circannual changes in free thyroxine, prolactin, testes, and relative food intake in woodchucks, Marmota monax. Am. J. Physiol. 277:R1401-R1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cote, P. J., B. E. Korba, R. H. Miller, J. R. Jacob, B. H. Baldwin, W. E. Hornbuckle, R. H. Purcell, B. C. Tennant, and J. L. Gerin. 2000. Effects of age and viral determinants on chronicity as an outcome of experimental woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Hepatology 31:190-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cote, P. J., C. Roneker, K. Cass, F. Schodel, D. Peterson, B. Tennant, F. De Noronha, and J. Gerin. 1993. New enzyme immunoassays for the serologic detection of woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Viral Immunol. 6:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullen, J. M., D. H. Li, C. Brown, E. J. Eisenberg, K. C. Cundy, J. Wolfe, J. Toole, and C. Gibbs. 2001. Antiviral efficacy and pharmacokinetics of oral adefovir dipivoxil in chronically woodchuck hepatitis virus-infected woodchucks. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2740-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cullen, J. M., S. L. Smith, M. G. Davis, S. E. Dunn, C. Botteron, A. Cecchi, D. Linsey, D. Linzey, L. Frick, M. T. Paff, A. Goulding, and K. Biron. 1997. In vivo antiviral activity and pharmacokinetics of (−)-cis-5-fluoro-1-[2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-oxathiolan-5-yl]cytosine in woodchuck hepatitis virus-infected woodchucks. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2076-2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai, C. Y., W. L. Chuang, M. Y. Hsieh, L. P. Lee, J. F. Huang, N. J. Hou, Z. Y. Lin, S. C. Chen, L. Y. Wang, J. F. Tsai, W. Y. Chang, and M. L. Yu. 2007. Adefovir dipivoxil treatment of lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antivir. Res. 75:146-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delaney, W. E., IV, H. Yang, M. D. Miller, C. S. Gibbs, and S. Xiong. 2004. Combinations of adefovir with nucleoside analogs produce additive antiviral effects against hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3702-3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dore, G. J., D. A. Cooper, A. L. Pozniak, E. DeJesus, L. Zhong, M. D. Miller, B. Lu, and A. K. Cheng. 2004. Efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in antiretroviral therapy-naive and -experienced patients coinfected with HIV-1 and hepatitis B virus. J. Infect. Dis. 189:1185-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadziyannis, S. J., N. C. Tassopoulos, E. J. Heathcote, T. T. Chang, G. Kitis, M. Rizzetto, P. Marcellin, S. G. Lim, Z. Goodman, J. Ma, S. Arterburn, S. Xiong, G. Currie, and C. L. Brosgart. 2005. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:2673-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadziyannis, S. J., N. C. Tassopoulos, E. J. Heathcote, T. T. Chang, G. Kitis, M. Rizzetto, P. Marcellin, S. G. Lim, Z. Goodman, M. S. Wulfsohn, S. Xiong, J. Fry, and C. L. Brosgart. 2003. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:800-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoff, J., F. Bani-Sadr, M. Gassin, and F. Raffi. 2001. Evaluation of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in coinfected patients receiving lamivudine as a component of anti-human immunodeficiency virus regimens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:963-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurwitz, S. J., B. C. Tennant, B. E. Korba, J. L. Gerin, and R. F. Schinazi. 1998. Pharmacodynamics of (′)-β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine in chronically virus-infected woodchucks compared to its pharmacodynamics in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2804-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurwitz, S. J., B. C. Tennant, B. E. Korba, I. Liberman, J. L. Gerin, and R. F. Schinazi. 2002. Viral pharmacodynamic model for (−)-beta-2′,3′-dideoxy-5-fluoro-3′-thiacytidine (emtricitabine) in chronically infected woodchucks. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 13:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob, J. R., B. E. Korba, P. J. Cote, I. Toshkov, W. E. Delaney IV, J. L. Gerin, and B. C. Tennant. 2004. Suppression of lamivudine-resistant B-domain mutants by adefovir dipivoxil in the woodchuck hepatitis virus model. Antivir. Res. 63:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain, M. K., L. Comanor, C. White, P. Kipnis, C. Elkin, K. Leung, A. Ocampo, N. Attar, P. Keiser, and W. M. Lee. 2007. Treatment of hepatitis B with lamivudine and tenofovir in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients: factors associated with response. J. Viral Hepat. 14:176-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korba, B. E., P. Cote, W. Hornbuckle, R. Schinazi, J. L. Gerin, and B. C. Tennant. 2000. Enhanced antiviral benefit of combination therapy with lamivudine and famciclovir against WHV replication in chronic WHV carrier woodchucks. Antivir. Res. 45:19-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korba, B. E., P. Cote, W. Hornbuckle, B. C. Tennant, and J. L. Gerin. 2000. Treatment of chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection in the Eastern woodchuck (Marmota monax) with nucleoside analogues is predictive of therapy for chronic hepatitis B virus infection in humans. Hepatology 31:1165-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korba, B. E., P. J. Cote, S. Menne, I. Toshkov, B. H. Baldwin, F. V. Wells, B. C. Tennant, and J. L. Gerin. 2004. Clevudine therapy with vaccine inhibits progression of chronic hepatitis and delays onset of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Antivir. Ther. 9:937-952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korba, B. E., R. F. Schinazi, P. Cote, B. C. Tennant, and J. L. Gerin. 2000. Effect of oral administration of emtricitabine on woodchuck hepatitis virus replication in chronically infected woodchucks. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1757-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuo, A., J. L. Dienstag, and R. T. Chung. 2004. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lacombe, K., J. Gozlan, P. Y. Boelle, L. Serfaty, F. Zoulim, A. J. Valleron, and P. M. Girard. 2005. Long-term hepatitis B virus dynamics in HIV-hepatitis B virus-co-infected patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. AIDS 19:907-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liaw, Y. F. 2001. Impact of YMDD mutations during lamivudine therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 12(Suppl. 1):67-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lok, A. S., and B. J. McMahon. 2007. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 45:507-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcellin, P., T. Asselah, and N. Boyer. 2005. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J. Viral Hepat. 12:333-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcellin, P., T. T. Chang, S. G. Lim, M. J. Tong, W. Sievert, M. L. Shiffman, L. Jeffers, Z. Goodman, M. S. Wulfsohn, S. Xiong, J. Fry, and C. L. Brosgart. 2003. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:808-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mason, W. S., J. Cullen, G. Moraleda, J. Saputelli, C. E. Aldrich, D. S. Miller, B. Tennant, L. Frick, D. Averett, L. D. Condreay, and A. R. Jilbert. 1998. Lamivudine therapy of WHV-infected woodchucks. Virology 245:18-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maynard, M., P. Parvaz, S. Durantel, M. Chevallier, P. Chevallier, M. Lot, C. Trepo, and F. Zoulim. 2005. Sustained HBs seroconversion during lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil combination therapy for lamivudine failure. J. Hepatol. 42:279-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menne, S., G. Asif, J. Narayanasamy, S. D. Butler, A. L. George, S. J. Hurwitz, R. F. Schinazi, C. K. Chu, P. J. Cote, J. L. Gerin, and B. C. Tennant. 2007. Antiviral effect of orally administered (−)-β-d-2-aminopurine dioxolane in woodchucks with chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3177-3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menne, S., and P. J. Cote. 2007. The woodchuck as an animal model for pathogenesis and therapy of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 13:104-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menne, S., P. J. Cote, B. E. Korba, S. D. Butler, A. L. George, I. A. Tochkov, W. E. Delaney IV, S. Xiong, J. L. Gerin, and B. C. Tennant. 2005. Antiviral effect of oral administration of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in woodchucks with chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2720-2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menne, S., C. A. Roneker, B. E. Korba, J. L. Gerin, B. C. Tennant, and P. J. Cote. 2002. Immunization with surface antigen vaccine alone and after treatment with 1-(2-fluoro-5-methyl-beta-l-arabinofuranosyl)-uracil (L-FMAU) breaks humoral and cell-mediated immune tolerance in chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. J. Virol. 76:5305-5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nash, K. L., and G. J. Alexander. 2008. The case for combination antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8:444-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson, M., S. Portsmouth, J. Stebbing, M. Atkins, A. Barr, G. Matthews, D. Pillay, M. Fisher, M. Bower, and B. Gazzard. 2003. An open-label study of tenofovir in HIV-1 and hepatitis B virus co-infected individuals. AIDS 17:F7-F10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nuesch, R., J. Ananworanich, P. Srasuebkul, P. Chetchotisakd, W. Prasithsirikul, W. Klinbuayam, A. Mahanontharit, T. Jupimai, K. Ruxrungtham, and B. Hirschel. 2008. Interruptions of tenofovir/emtricitabine-based antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV/hepatitis B virus co-infection. AIDS 22:152-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nunez, M., M. Perez-Olmeda, B. Diaz, P. Rios, J. Gonzalez-Lahoz, and V. Soriano. 2002. Activity of tenofovir on hepatitis B virus replication in HIV-co-infected patients failing or partially responding to lamivudine. AIDS 16:2352-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peek, S. F., P. J. Cote, J. R. Jacob, I. A. Toshkov, W. E. Hornbuckle, B. H. Baldwin, F. V. Wells, C. K. Chu, J. L. Gerin, B. C. Tennant, and B. E. Korba. 2001. Antiviral activity of clevudine [L-FMAU, (1-(2-fluoro-5-methyl-beta, L-arabinofuranosyl) uracil)] against woodchuck hepatitis virus replication and gene expression in chronically infected woodchucks (Marmota monax). Hepatology 33:254-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters, M. G., H. W. Hann, P. Martin, E. J. Heathcote, P. Buggisch, R. Rubin, M. Bourliere, K. Kowdley, C. Trepo, D. F. Gray, M. Sullivan, K. Kleber, R. Ebrahimi, S. Xiong, and C. L. Brosgart. 2004. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 126:91-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qi, X., S. Xiong, H. Yang, M. Miller, and W. E. Delaney IV. 2007. In vitro susceptibility of adefovir-associated hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations to other antiviral agents. Antivir. Ther. 12:355-362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]