Abstract

Children and immunocompromised adults are at an increased risk of tuberculosis (TB), but diagnosis is more challenging. Recently developed gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release assays provide increased sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of latent TB, but their use is not FDA approved in immunocompromised or pediatric populations. Both populations have reduced numbers of T cells, which are major producers of IFN-γ. Interleukin 7 (IL-7), a survival cytokine, stabilizes IFN-γ message and increases protein production. IL-7 was added to antigen-stimulated lymphocytes to improve IFN-γ responses as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. Antigens used were tetanus toxoid (n = 10), p24 (from human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], n = 9), and TB peptides (n = 15). Keyhole limpet hemocyanin was used as a negative control, and phytohemagglutinin was the positive control. IL-7 improved antigen-specific responses to all antigens tested including tetanus toxoid, HIV type 1 p24, and TB peptides (ESAT-6 and CFP-10) with up to a 14-fold increase (mean = 3.8), as measured by ELISA. Increased IFN-γ responses from controls, HIV-positive patients, and TB patients were statistically significant, with P values of <0.05, 0.01, and 0.05, respectively. ELISPOT assay results confirmed ELISA findings (P values of <0.01, 0.02, and 0.03, respectively), with a strong correlation between the two tests (R2 = 0.82 to 0.99). Based on average background levels, IL-7 increased detection of IFN-γ by 39% compared to the level with antigen alone. Increased production of IFN-γ induced by IL-7 improves sensitivity of ELISA and ELISPOT assays for all antigens tested. Further enhancement of IFN-γ-based assays might improve TB diagnosis in those populations at highest risk for TB.

Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release assays have been used to detect both latent and active tuberculosis (TB). Compared to the century-old tuberculin skin test (TST), these assays have increased specificity and sensitivity for TB diagnosis in select populations (31-34). IFN-γ-based assays are more predictive than the TST in diagnosing active TB in both human immunodeficiency virus-positive (HIV+) and pediatric populations (5, 10, 33). However, the FDA has limited the approved use of IFN-γ-based assays for TB diagnosis to adult non-HIV+ populations. The reduced number of IFN-γ-producing T cells in both HIV+ and pediatric populations likely limits the sensitivity and specificity of these assays (25, 35). Those who are truly infected with TB may be misclassified as negative (type II error) and would therefore potentially forego treatment. Indeed, an 85% drop in the need for treatment for TB was reported when a combination of TST and QuantiFERON Gold (QFT-G) testing was performed (47). False-negative results for TST but not with QFT-G are seen in HIV-infected adults (33). The inability to confidently diagnose these patients impacts both TB control and drug-resistant TB prevalence (43). For HIV-infected persons, the risk for developing TB doubles within 1 year of infection (43). For children, the risk of disease after exposure increases up to 80%, especially in those with HIV infection (30).

Increased diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for TB infection would improve case management, prevent unnecessary exposure to strong chemoprophylaxis, impact TB control, and increase epidemiologic knowledge (28). For these reasons, improvement of IFN-γ assays has been recognized as a health priority (21, 30). The main goal of this study was to increase the amount of IFN-γ secreted or the number of effector cells after antigen-specific stimulation, which might lead to improved sensitivity and specificity of IFN-based assays. The long-term goal is to improve TB diagnosis in both HIV+ and pediatric populations.

Interleukin-7 (IL-7) functions in T-cell development and homeostasis (11, 12). It stabilizes IFN-γ message, enhances cell viability, and is being studied as a treatment to improve T-cell responses (3, 4, 24, 27, 37, 39, 44, 48). A recent publication shows that recombinant human IL-7 preferentially expands naïve T cells and central memory CD4+ T cells, without regulatory T-cell (T-reg) expansion (44). IL-7 and IL-15 enhance enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay responses to purified protein derivative and cytomegalovirus antigens (24). An additional study used this same combination of cytokines and measured HIV type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell responses in children in the Bronx (New York, NY) (42).

The two most heavily studied IFN-γ-based assays for TB diagnosis are the QFT-G assay (Cellestis) and the T-Spot TB (Oxford Immunotec). The QFT-G uses enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques to quantify the amount of IFN-γ from whole-blood cultures 24 h after stimulation (Cellestis QuantiFERON-TB Gold package insert; Cellestis, Valencia, CA). The T-Spot TB uses isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) so that a known quantity of cells (2.5 × 105) is used in the assay. The counted cells are incubated with antigen, and the number of antigen-specific cells is measured 16 to 20 h after stimulation (10). Studies exploring the correlation between these assays and the TST have yielded mixed results, likely because of differences in the numbers of cells used in the assays (2, 8, 10, 26, 34). Studies have not directly compared the T-Spot and QFT-G assays on identical counted cell populations with the same antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects.

HIV+ and control subjects were adults (18 years or older) who had given informed written consent. All work completed on donated blood was performed under study protocols approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Control subjects (n = 10) had no prior diagnosis of TB or HIV. HIV+ patients (n = 9) were either part of an ongoing study examining long-term HIV+ survivors or current patients at a local clinic. All HIV+ subjects had CD4 counts of 200 or greater. All TB patients (TB+) (n = 15) were known to be QFT-G positive by the whole-blood method. These were subjects enrolling in the Houston Tuberculosis Initiative Project (42a). Individual participants gave informed, written consent prior to submission of clinical specimens, which were then blinded to preserve patient confidentiality. Thus, all TB patients tested in this study were known to be QFT-G positive.

Optimization of incubation period.

Human peripheral blood was obtained from healthy donors and HIV+ donors. PBMCs were isolated by centrifugation with Histopaque-1077 density gradients. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer, and viability was assessed using trypan blue dye; viability was between 90 and 95%. Cells were cultured in 24-well plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) at a concentration of 1 × 106/ml/well. PBMCs cultured in RPMI plus 10% fetal calf serum medium alone served as a negative control, and phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 2 μg/ml) served as a positive control. QuantiFERON CMI kits were used to quantitate the amount of IFN-γ in cell culture supernatants.

Dose response of IL-7.

Cells from healthy donors were incubated with different concentrations of IL-7, ranging from 1 ng/ml to 20 ng/ml, to construct titration curves, with and without PHA at 2 μg/ml. Activation of the cultured PBMCs was analyzed by flow cytometry analysis using CD69, CD25, and HLA-DR monoclonal conjugated antibodies, as well as annexin V binding. The ability of IL-7 to increase the antigen-specific response to different peptides in healthy subjects' PBMCs and those from HIV-infected patients was assessed by incubation of 1 × 106 cells/ml with tetanus toxoid (1 μg/ml) and keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH; 1 μg/ml).

Postoptimization PBMC isolation and culture.

PBMCs were isolated from 2 to 60 ml of lithium heparin-treated whole blood (BD Vacutainer 7068027) using Histopaque density gradient centrifugation. PBMCs for control and HIV+ populations were isolated within 8 h of collection. PBMCs for TB+ patients were isolated more than 24 h after collection because a positive QFT-G result was required to use the sample for testing with our improved assay. Cells were resuspended in AIM-V medium (Gibco 12055, Invitrogen). Viability of the cells was examined by trypan blue exclusion (Cellgro MT 25-900-CI; Invitrogen). PBMCs of all patients were stimulated using the following conditions: no addition; 10 ng recombinant human IL-7 (R & D Systems); KLH (15) (Calbiochem), 1 μg/ml for controls and HIV+ patients or 8 μg/ml for TB patients; KLH plus IL-7 at 10 ng/ml; PHA (Sigma-Aldrich catalog no. 61764) at 1 μg/ml or 8 μg/ml; and the antigens tetanus toxoid (List Biological Laboratories catalog no. 191A) and HIV-1 p24 (Protein Science Corp. catalog no. 5834) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml or TB peptides ESAT-6 and CFP-10 at 2 μg/ml each for a final concentration of 8 μg/ml (Baylor College of Medicine protein core, Houston, TX). Treated PBMCs were either transferred to 96-well plates (Costar) after stimulation and incubated for 24 h or placed dropwise into ELISPOT assay wells (Oxford Immunotec) and incubated for 20 h at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Antigen preparation.

Corresponding overlapping mixtures of RD1 coded peptides from ESAT-6 and CFP-10 are as effective at eliciting immune responses as are the more expensive whole-protein antigen counterparts (1, 40). Peptides from ESAT-6 and CFP-10 were selected for use in testing TB responses (Table 1) and synthesized in the Baylor College of Medicine protein core using ferrimannitol ovalbumin chemistry on an ABI433A peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems Inc.). They were purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography and verified by mass spectrometry and amino acid analysis.

TABLE 1.

Synthetic peptides used in this study

| Proteina | Peptide | Positions | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESAT-6 | P4 | 31-50 | EGKQSLTKLAAAWGGSGSEA |

| P7 | 61-80 | TATELNNALQNLARTISEAG | |

| CFP-10 | P6 | 51-70 | AQAAVVRFQEAANKQKQELD |

| P8 | 71-90 | EISTNIRQAGOVQYSRADEEQ |

ESAT-6, 6-kDa early secreted antigenic target from Mycobacterium tuberculosis; CFP-10, 10-kDa culture filtrate protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

ELISA.

QFT-G assay kits (Cellestis) were used for ELISA determinations. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were centrifuged and supernatants were collected. Conjugate (murine anti-human IFN-γ horseradish peroxidase) (50 μl) was diluted in a mixture of bovine casein, normal mouse serum, and 0.01% thimerosal and added to precoated plates. Samples and standards were layered on top and allowed to incubate for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed for a minimum of six cycles. Substrate (hydrogen peroxide and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) was added to each well, and a 30-min room-temperature incubation followed. After incubation, stop solution (0.5 M H2SO4) was added and optical densities were read using 450- and 630-nm filters (Dynex MRX II). Measured optical densities were converted to IU/ml based on the standard curve specific for each plate.

ELISPOT.

T-Spot TB kits (Oxford Immunotec) were used to determine the number of IFN-γ-producing cells by ELISPOT assay. After 20 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were discarded and the plate was washed using 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) per well. After the plate was washed three times, 50 μl of PBS-diluted conjugate (murine anti-human alkaline phosphatase-conjugated IFN-γ) was added. The plate was then incubated at 2 to 8°C for 1 h. The conjugate was discarded from the plate followed by four washes with PBS. Substrate (BCIP/NBTplus solution; 50 μl) was added, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 7 min. The plate was washed and allowed to dry. IFN-γ production was indicated by counting spots using an automated reader (CTL Immunospot S4). Blinded counts were verified using a stereoscope.

Statistical analysis.

The data obtained are presented as means and differences between means and were assessed using the Student t test. Power analysis, using mean differences from control patients, indicated that a minimum of nine patients of each group would be necessary to achieve statistical significance. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant for HIV+ patients (n = 9), TB+ patients stimulated at 2.5 × 106 (n = 9), and control patients (n = 10). In addition, for all patients, t test findings were verified using Wilcoxon signed-rank analysis. Using the calculated means, we correlated the ELISPOT assays and ELISAs for individual patients and report the coefficient of determination (R2).

RESULTS

Dose response of IL-7.

Because IL-7 is a survival cytokine for T cells (24, 37) and is important in homeostasis of human T cells (11), the addition of IL-7 was used to see whether activation would be enhanced. We found that CD25 but not CD69 or DR was upregulated after addition of IL-7 to PBMCs from control volunteers, confirming other results (see Fig. S1a and S1b in the supplemental material) (6, 41). However, upregulation of CD25 expression occurred only on CD4+ and not CD8+ T cells, indicating a specific subpopulation effect when IL-7 was added without other factors. IL-7 at 2 ng/ml increased CD25 expression levels (P = 0.03), and the addition of up to 20 ng/ml had no increased effect on CD25 levels (see Fig. S1c in the supplemental material). No increase in CD69 or DR expression was observed after IL-7 addition. No consistent increase of viability was noted as measured by annexin V staining. However, IL-7 enhanced the response to PHA as measured by increased levels of CD25 expression (see Fig. S1c in the supplemental material). In these cultures, after PHA stimulation, the CD8+ T cells also expressed higher levels of CD25 after IL-7 addition. IL-7 also increased the amount of IFN-γ produced as detected by ELISA.

Optimization of incubation period.

We then tested for an antigen-specific effect caused by IL-7 addition by using tetanus toxoid and p24 as antigens. However, 72 h of incubation resulted in elevated background IFN-γ production such that naïve T cells could have been primed (29). IL-7 and dexamethasone treatment of cord blood cells causes maturation of T cells into effector memory cells (46). IL-7 also promotes transition of T effectors to T memory cells, at least in the mouse (27). Therefore, we reduced the incubation time to 24 h. Results show that tetanus toxoid responses and not KLH responses (nonspecific antigen control) were improved by IL-7 addition (data not shown). Likewise no response above background to HIV p24 or TB peptides was seen in six controls in assays using p24 as antigen and four controls in assays using TB peptides as antigen after 24 h (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that IL-7 augments antigen-specific T-cell IFN-γ responses as detected by ELISA after 24 h. An increased response to IL-7 alone or de novo induction of naïve cells apparently can occur after 72 h of exposure to IL-7 (29).

Rationale for use of PMBCs.

Although our primary goal in these studies was to improve IFN-γ detection in TB diagnosis, it was important to examine the robustness of improvement of IFN-γ responses in both healthy individuals and people with chronic HIV or suspected TB infection. Therefore, we studied lymphocytic responses to tetanus toxoid, p24, and TB peptides after IL-7 addition.

We chose to perform these assays with separated PBMCs, not with whole blood, to quantify and thereby use the same number of responding cells for all comparisons. Use of PBMCs also avoided the complication of adding IL-7 to the complex milieu of whole blood.

Concentration of PBMCs.

All patients tested for latent infection by the Houston Tuberculosis Initiative (42a) had a separate tube of blood set aside for use in this study. To reduce the cost of testing all suspect TB cases, patient samples were not used until the QFT-G test was positive (≥0.35 IU IFN-γ) which was 24 to 36 h after blood was obtained. PBMCs of positive patients were then isolated and stimulated. Our initial procedure of stimulating 250,000 cells in 250 μl of medium led to IFN-γ production below that recorded 24 h earlier in the initial QFT-G test. We suspected that the lack of response (without IL-7 addition) might be because the cells were from blood that was 24 h old. However, by increasing the cell-to-volume ratio to increase the concentration of cells, we restored the amount of IFN-γ detected. This increase in cell concentration was done in nine TB patients, using 250,000 PBMCs resuspended in either 33 μl, 100 μl, or 250 μl to achieve a final concentration of 7.5 × 106, 2.5 × 106, and 1.0 × 106 cells/ml (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and in one control, using different numbers of PBMCs at various volumes (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The data show that, as the cell volume is decreased, the TB peptide response increases (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The addition of IL-7 to 500,000 antigen-stimulated PBMCs suspended in 50 μl of medium produced over 17 IU/ml of IFN-γ compared to the amount produced by 500,000 PBMCs in 100 μl (13.5 IU/ml) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Importantly, as the concentration of PBMCs increased to raise the number of effector memory cells, the background level of IFN-γ measured in response to IL-7 stimulation remained consistent.

IFN-γ detected by ELISA.

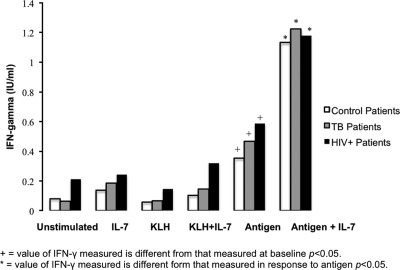

After optimization of the assay by reducing the volume, we studied PBMCs from 28 subjects. These included 10 controls stimulated with tetanus toxoid, nine subjects with confirmed TB stimulated with TB peptides, and nine HIV+ patients stimulated with HIV-1 p24. The cells were incubated for 24 h with no stimulation, with antigen (tetanus toxoid, TB peptides, or HIV-1 p24), with negative-control KLH antigen, and with positive-control stimulation (PHA). The amount of IFN-γ detected using KLH, with and without IL-7, remained statistically insignificant compared to that for unstimulated cultures and cultures stimulated with IL-7 alone (P, 0.2 and 0.6, respectively), meaning that there was no difference between the negative control (KLH) and the unstimulated samples after IL-7 addition. However, after stimulation of PBMCs with antigens, up to a 14-fold increase (mean, 3.8) in IFN-γ level was seen after IL-7 supplementation with statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) for all patients. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were also seen when comparing the amounts of IFN-γ detected from unstimulated and negative-control supernatants with and without IL-7 with amounts detected from antigen-stimulated supernatants (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

IL-7 enhances IFN-γ production from antigen-stimulated lymphocytes. Cells were incubated for 24 h with medium, 10 ng IL-7, KLH (negative-control antigen), KLH plus IL-7, antigen (tetanus toxoid, HIV p24, or TB peptides), or antigen plus IL-7 (n = 28). Supernatants were then assayed for IFN-γ using ELISA. IL-7 enhances antigen-specific responses 2- to 14-fold in all patients (P < 0.01), in 9 of 10 control patients (P < 0.05), in eight of the nine TB patients (P = 0.05), and in eight of the nine HIV+ patients (P = 0.01). Positive-control values (PHA, 1.0 μg/ml) are not shown, as all positive controls produced IFN-γ at levels above background with values ranging from 0.43 to 81.3 IU/ml. Statistically significant differences were also seen between the IFN-γ levels produced in response to antigen and the levels produced by unstimulated and negative controls (P < 0.05).

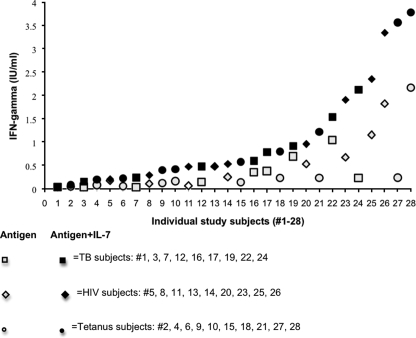

The FDA-approved QFT-G test defines a positive test as 0.35 IU/ml or greater. Using the QFT-G reference cutoff to distinguish positive IFN-γ values from negative IFN-γ values for comparison, IL-7 increased detection of IFN-γ by 39% (from 32% [9/28] to 71% [20/28]), despite the 24-h delay in stimulation for the confirmed QFT-G TB+ subjects. Based on these values, IL-7 addition increased sensitivity by more than 20% for each study population. Increases were evenly distributed with values as follows: TB, range of 1.26 to 9.2, mean of 3.6, and median of 2.1; HIV, range of 1.0 to 7.3, mean of 3.7, and median of 2.5; and controls, range of 1.6 to 14.8, mean of 3.2, and median of 3.1 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Addition of IL-7 increases ELISA sensitivity. The FDA-approved QFT-G defines a positive result as 0.35 IU/ml or greater. This graph displays the increased sensitivity in response to antigen stimulation after addition of IL-7 in all study subjects (10 controls, nine TB patients, and nine HIV+ patients). Increases with the addition of IL-7 were evenly distributed in each study group: TB response to TB peptides (range = 1.26 to 9.2, mean = 3.6, median = 2.1), HIV response to HIV-1 p24 (range = 1.0 to 7.3, mean = 3.5, median = 2.8), and control response to tetanus toxoid (range = 1.6 to 14.8, mean = 3.2, median = 3.1). When the QFT-G value of 0.35 IU/ml is used, IL-7 increased sensitivity, from 30% (7/23) to 70% (16/23).

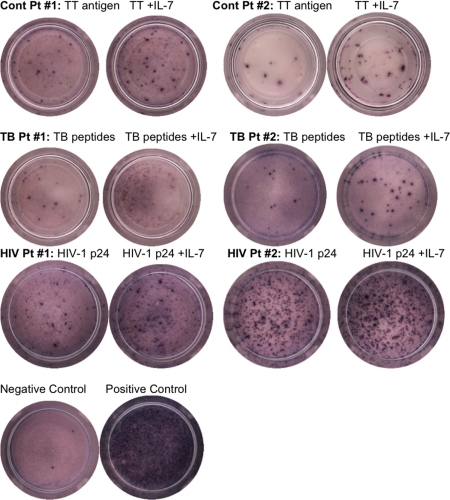

IFN-γ effector cells detected by ELISPOT assay.

PBMCs from 18 patients (10 controls, four QFT-G-confirmed latent TB patients, and four HIV+ patients) were incubated for 20 h under each condition separately (Fig. 3). The number of individual T cells secreting IFN-γ after negative-control stimulation by KLH, with and without the addition of IL-7, from all patients remained statistically insignificant compared with the number of T cells from unstimulated cultures and cultures stimulated with IL-7 alone. However, in response to antigen up to a 16-fold increase (mean, 3.4) in ELISPOT assays occurred after the addition of IL-7 with statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) for all patients. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were also observed when comparing the numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells from unstimulated cell and negative-control supernatants with and without IL-7 with those from antigen-stimulated supernatants with and without IL-7. Raw data from four subjects in each group are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Overall the ELISPOT assay results mirrored and confirmed the QFT-G findings.

FIG. 3.

Increase in effector cell number with IL-7 addition. Cells were incubated in ELISPOT plates for 20 h with medium alone, 10 ng IL-7, KLH (negative-control antigen), KLH plus IL-7, antigen (tetanus toxoid [TT], HIV p24, or TB peptides (ESAT-6 and CFP-10), or antigen plus IL-7 (n = 18). Plates were developed, and spots were counted using an automated reader. IL-7 enhances antigen-specific responses up to 16-fold (mean = 3) in all patients (P < 0.01), in all control patients (P < 0.01), in all TB patients (P = 0.03), and in all of the HIV+ patients (P = 0.02). Statistically significant differences were also seen between the IFN-γ levels produced in response to antigen and the levels produced by unstimulated and negative controls (P < 0.05).

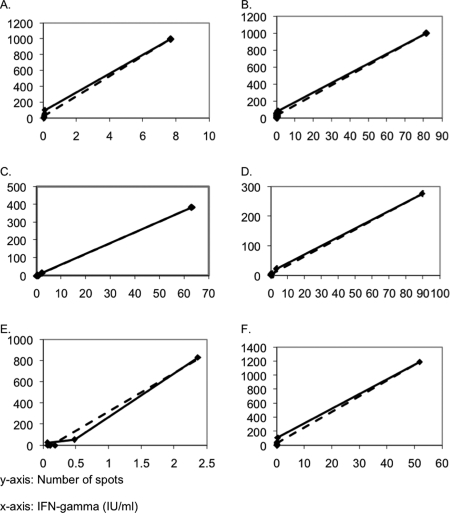

ELISPOT/ELISA correlation.

We isolated PBMCs and then used stimulating conditions previously described prior to performing the ELISA and ELISPOT assays. We found that ELISA detection of IFN-γ correlated well with the number of spots detected by ELISPOT assay (Fig. 4). For control patients the ELISA and ELISPOT results gave similar individual coefficients of determination with a range of 0.92 to 1.0 (μ = 0.98, σ = 0.04). For HIV+ patients and TB patients, the range of individual coefficients of determination was 0.83 to 0.99 (μ = 0.92, σ = 0.08) and 0.93 to 0.99 (μ = 0.98, σ = 0.02), respectively. The mean coefficient for all patients tested using both diagnostic techniques was R2 = 0.96 with a standard deviation of 0.05.

FIG. 4.

Correlations between ELISA and ELISPOT results for two tetanus toxoid-stimulated control patients (A and B), two TB+ peptide-stimulated patients (C and D), and two HIV+ HIV-1 p24-stimulated patients (E and F). Correlations include ELISA and ELISPOT results for all conditions and are specific to the individual patients. Coefficient of determination values for graphs shown are two examples from each population sampled: controls (A [R2 = 0.99] and B [R2 = 0.99]), tetanus toxoid patients (C [R2 = 0.99] and D [R2 = 0.99]), and HIV+ patients (E [R2 = 0.99] and F [R2 = 0.99]).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we measured the effects of IL-7 on IFN-γ production in cells from three different groups of subjects. IL-7 enhanced antigen-specific responses 2- to 14-fold in all patients (P < 0.01), in 9 of 10 control patients with tetanus toxoid stimulation (P < 0.05), in eight of the nine TB patients (P = 0.05), and in eight of the nine HIV+ patients (P = 0.01) (n = 9) (Fig. 2). IL-7 did not enhance non-antigen-specific responses as shown by the use of IL-7 alone and the negative control, KLH. Our results confirm and add to the findings of Jennes et al. (22). Using the QFT-G value of 0.35 IU/ml defined as a positive test, for comparative purposes, more than a 20% increase in the amount of IFN-γ was found for each population studied (controls and HIV+ and TB+ patients) with an overall improvement of 39%.

The increased IFN-γ production in both healthy controls and diseased people is an important finding because other factors can impair IFN-γ production and confound responses in both TB and HIV+ patients (17-19). The decreased ability to produce detectable levels of IFN-γ in people with TB has been attributed to the effects of increased levels of T-regs (14, 38) and transforming growth factor β (11, 18) and could also be due to increased cellular apoptosis (16). Spontaneous and antigen-induced programmed cell death levels are elevated in patients with TB compared to control subjects (16, 17). T-regs are increased threefold during active TB infection and can reduce IFN-γ responses (33, 38). In HIV-infected people, naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ T-regs suppress both CD4+ and CD8+ cell responses (23). In addition, highly active antiretroviral therapy suppresses viral loads to stabilize or increase the number of CD4+ cells and, in turn, actually decreases responsiveness to HIV antigens (36). Some of these mechanisms, such as a decrease in T-regs, are reduced by IL-7 (20, 39) and may be a further explanation for our finding of increased production of IFN-γ upon IL-7 addition. However, a key factor is that numbers of T memory cells are reduced in HIV infection.

Higher levels of IFN-γ were detected from the same number of PBMCs if the volume was reduced. This was first noticed in our TB population (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) and confirmed with tetanus toxoid stimulation in a control (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The response to IL-7 addition alone, however, remained unchanged. By increasing the cell-to-volume ratio and theoretically cell-to-cell interactions, we increased the amount of IFN-γ without increasing the background level of IFN-γ. We propose that by decreasing the volume, thereby crowding the cells, the probability of receptor-ligand interactions and potentially the sampling of antigen by dendritic cells were increased. Further studies are in progress to determine key players in the upregulation of IFN-γ production caused by IL-7 addition.

As possible evidence that IFN-γ production by antigen-specific cells may provide a method for detection of the response to infection, a previous study compared amounts of IFN-γ in response to purified protein derivative, ESAT-6, and PHA, using ELISA, ELISPOT, and reverse transcription-PCR techniques. This study reported that antigen stimulation with ESAT-6 peptide increased IFN-γ mRNA levels exponentially, but similar increases in IFN-γ protein production were not found (9). This indicates that inhibition in translation may be present. In light of this study and the known ability of IL-7 to stabilize IFN-γ message, we suggest that IL-7 allows more protein to be processed from the induced or existing message, an idea which will be tested in future studies. By using IL-7 to increase and stabilize IFN-γ production, latently infected individuals with few or impaired effector cells have an increased probability of being detected as TB reactive.

To examine whether increased IFN-γ production resulted in an increase in the number of effector cells, we used ELISPOT assays (Fig. 3). Our findings of increased effector cell numbers after addition of IL-7 are in agreement with previous results from cryopreserved specimens (22).

Since the development of IFN-γ-based assays, many studies have compared their effectiveness to that of the TST. Findings of improved sensitivity vary widely, and the most recent study showed concern about the negative predictive value of IFN-γ-based assays compared to that of TST (7). The QFT-G assay tests for TB by stimulating 1 ml of whole blood, and the ELISPOT assay relies on isolation of PBMCs prior to antigen stimulation. When we tested with the same cells and antigens, we found that results from ELISA and ELISPOT assays correlated well (Fig. 4). The mean correlation coefficient (R2) for all patients tested using both diagnostic techniques was 0.96. This correlation is higher than that previously reported (13) and indicates that IL-7 increases the amount of IFN-γ produced by increasing the number of responding effector cells and that QFT-G and ELISPOT tests detect IFN-γ with nearly equal sensitivities. Other studies comparing these two assays have been compromised by dissimilar incubation times and stimulation conditions (9, 31). The failure to count the number of cells and adjust the concentration used is also an inherent limitation of the whole-blood assay, especially in cases where CD4 numbers are reduced, as in HIV infection.

A current limitation of IFN-γ-based assays is the requirement of sample processing within 12 h of collection (Cellestis QuantiFERON-TB Gold package insert). This is especially difficult in resource-poor countries. Indeed, discrepancies from two different sites in Africa correlated with the time that it took to process the samples (9). We show that, after IL-7 addition, TB-specific IFN-γ can still be detected despite a greater-than-24-h period between blood collection and PBMC isolation. This may be due to message stabilization by IL-7 and/or enhancement of viability, which we will examine in future studies.

In conclusion, IL-7 increases IFN-γ detection in response to antigen, which has important public health implications. Improvement of IFN-γ diagnostic sensitivity might result in improvement in the detection of latent infection, the treatment of pediatric and HIV-infected individuals, and strengthened TB control. Further studies will investigate if IL-7 acts similarly in pediatric TB patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 August 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://cvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arend, S. M., A. Geluk, K. E. van Meijgaarden, J. T. van Dissel, M. Theisen, P. Andersen, and T. H. Ottenhoff. 2000. Antigenic equivalence of human T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1-encoded protein antigens ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10 and to mixtures of synthetic peptides. Infect. Immun. 68:3314-3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arend, S. M., S. F. T. Thijsen, E. M. S. Leyten, J. J. M. Bouwman, W. P. J. Franken, B. F. Koster, F. G. J. Cobelens, A. J. van Houte, and A. W. J. Bossink. 2007. Comparison of two interferon-gamma assays and tuberculin skin test for tracing tuberculosis contacts. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175:618-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazdar, D. A., and S. F. Sieg. 2007. Interleukin-7 enhances proliferation responses to T-cell receptor stimulation in naïve CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. J. Virol. 81:12670-12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borger, P., H. F. Kauffman, D. S. Postma, and E. Vellenga. 1996. IL-7 differentially modulates the expression of IFN-gamma and IL-4 in activated human T lymphocytes by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. J. Immunol. 156:1333-1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman, A. L. N., M. Munkanta, K. A. Wilkinson, A. A. Pathan, K. Ewer, H. Ayles, W. H. Reece, A. Mwinga, P. Godfrey-Faussett, and A. Lalvani. 2002. Rapid detection of active and latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-positive individuals by enumeration of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cells. AIDS 16:2285-2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung, I. Y., H. F. Dong, X. Zhang, N. M. A. Hassanein, O. M. Z. Howard, J. J. Oppenheim, and X. Chen. 2004. Effects of IL-7 and dexamethasone: induction of CD25, the high affinity IL-2 receptor, on human CD4+ cells. Cell. Immunol. 232:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connell, T. G., N. Ritz, G. A. Paxton, J. P. Buttery, N. Curtis, and S. C. Ranganathan. 2008. A three-way comparison of tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB Gold and T-SPOT, TB in children. PLoS ONE 3:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detjen, A. K., T. Keil, S. Roll, B. Hauer, H. Mauch, U. Wahn, and K. Magdorf. 2007. Interferon-γ release assays improve the diagnosis of tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in children in a country with a low incidence of tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:322-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doherty, T. M., A. Demissie, D. Menzies, P. Andersen, G. Rook, and A. Zumla. 2005. Effect of sample handling on analysis of cytokine responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples using ELISA, ELISPOT and quantitative PCR. J. Immunol. Methods 298:129-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewer, K., J. Deeks, L. Alvarez, G. Bryant, S. Waller, P. Andersen, P. Monk, and A. Lalvani. 2003. Comparison of T-cell-based assay with tuberculin skin test for diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a school tuberculosis outbreak. Lancet 361:1168-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fry, T. J., E. Connick, J. Falloon, M. M. Lederman, D. J. Liewehr, J. Spritzler, S. M. Steinberg, L. V. Wood, R. Yarchoan, J. Zuckerman, A. Landay, and C. L. Mackall. 2001. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood 97:2983-2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fry, T. J., and C. L. Mackall. 2002. Interleukin-7: from bench to clinic. Blood 99:3892-3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goletti, D., D. Vincenti, S. Carrara, O. Butera, F. Bizzoni, G. Bernardini, M. Amicosante, and E. Girardi. 2005. Selected RD1 peptides for active tuberculosis diagnosis: comparison of a gamma interferon whole-blood enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and an enzyme-linked immunospot assay. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:1311-1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyot-Revol, V., J. A. Innes, S. Hackforth, T. Hinks, and A. Lalvani. 2006. Regulatory T cells are expanded in blood and disease sites in patients with tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173:803-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris, J. R., and J. Markl. 1999. Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH): a biomedical review. Micron 30:597-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertoghe, T., A. Wajja, L. Ntambi, A. Okwera, M. A. Aziz, C. Hirsch, J. Johnson, Z. Toossi, R. Mugerwa, P. Mugyenyi, R. Colebunders, J. Ellner, and G. Vanham. 2000. T cell activation, apoptosis and cytokine dysregulation in the (co)pathogenesis of HIV and pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). Clin. Exp. Immunol. 122:350-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch, C. S., Z. Toossi, J. L. Johnson, H. Luzze, L. Ntambi, P. Peters, M. McHugh, A. Okwera, M. Joloba, P. Mugyenyi, R. D. Mugerwa, P. Terebuh, and J. J. Ellner. 2001. Augmentation of apoptosis and interferon-gamma production at sites of active Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in human tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 183:779-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsch, C. S., Z. Toossi, C. Othieno, J. L. Johnson, S. K. Schwander, S. Robertson, R. S. Wallis, K. Edmonds, A. Okwera, R. Mugerwa, P. Peters, and J. J. Ellner. 1999. Depressed T-cell interferon-gamma responses in pulmonary tuberculosis: analysis of underlying mechanisms and modulation with therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 180:2069-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hougardy, J., S. Place, M. Hildebrand, A. Drowart, A. Debrie, C. Locht, and F. Mascart. 2007. Regulatory T cells depress immune responses to protective antigens in active tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176:409-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, M., S. Sharma, L. X. Zhu, M. P. Keane, J. Luo, L. Zhang, M. D. Burdick, Y. Q. Lin, M. Dohadwala, B. Gardner, R. K. Batra, R. M. Strieter, and S. M. Dubinett. 2002. IL-7 inhibits fibroblast TGF-beta production and signaling in pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 109:931-937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine. 2000. Ending neglect: the elimination of tuberculosis in the United States. National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed]

- 22.Jennes, W., L. Kestens, D. F. Nixon, and B. L. Shacklett. 2002. Enhanced ELISPOT detection of antigen-specific T cell responses from cryopreserved specimens with addition of both IL-7 and IL-15—the Amplispot assay. J. Immunol. Methods 270:99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinter, A. L., M. Hennessey, A. Bell, S. Kern, Y. Lin, M. Daucher, M. Planta, M. McGlaughlin, R. Jackson, S. F. Ziegler, and A. S. Fauci. 2004. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells from the peripheral blood of asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals regulate CD4+ and CD8+ HIV-specific T cell immune response in vitro and are associated with favorable clinical markers of disease status. J. Exp. Med. 200:331-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondrack, R. M., J. Harbertson, J. T. Tan, M. E. McBreen, C. D. Surh, and L. M. Bradley. 2003. Interleukin 7 regulates the survival and generation of memory CD4 cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:1797-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalvani, A., and K. A. Millington. 2007. T cell-based diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 20:264-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leyten, E. M. S., S. M. Arend, C. Prins, F. G. J. Cobelens, T. H. M. Ottenhoff, and J. T. van Dissel. 2007. Discrepancy between Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific gamma interferon release assays using short and prolonged in vitro incubation. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:880-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, J., G. Huston, and S. L. Swain. 2003. IL-7 promotes the transition of CD4 effectors to persistent memory cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:1807-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lobato, M. N., J. C. Mohle-Boetani, and S. E. Royce. 2000. Missed opportunities for preventing tuberculosis among children younger than five years of age. Pediatrics 106:e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Managlia, E. Z., A. Landay, and L. Al-Harthi. 2005. Interleukin-7 signaling is sufficient to phenotypically and functionally prime human CD4 naïve T cells. Immunology 114:322-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marais, B. J., S. M. Graham, M. F. Cotton, and N. Beyers. 2007. Diagnostic and management challenges for childhood tuberculosis in the era of HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 196(Suppl. 1):S76-S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazurek, G. H., P. A. LoBue, C. L. Daley, J. Bernardo, A. A. Lardizabal, W. R. Bishai, M. F. Iademarco, and J. S. Rothel. 2001. Comparison of a whole-blood interferon gamma assay with tuberculin skin testing for detecting latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. JAMA 286:1740-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazurek, G. H., J. Jereb, P. Lobue, M. F. Iademarco, B. Metchock, and A. Vernon. 2005. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Recommend. Rep. 54:49-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazurek, G. H., S. E. Weis, P. K. Moonan, C. L. Daley, J. Bernardo, A. A. Lardizabal, R. R. Reves, S. R. Toney, L. J. Daniels, and P. A. LoBue. 2007. Prospective comparison of the tuberculin skin test and 2 whole-blood interferon-gamma release assays in persons with suspected tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:837-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pai, M., L. W. Riley, and J. M. Colford. 2004. Interferon-gamma assays in the immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4:761-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piana, F., L. R. Codecasa, G. Besozzi, G. B. Migliori, and D. M. Cirillo. 2006. Use of commercial interferon-gamma assays in immunocompromised patients for tuberculosis diagnosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173:130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitcher, C. J., C. Q. Quittner, D. M. Peterson, M. Connors, R. A. Koup, V. C. Maino, and L. J. Picker. 1999. HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cells are detectable in most individuals with active HIV-1 infection, but decline with prolonged viral suppression. Nat. Med. 5:518-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathmell, J. C., E. A. Farkash, W. Gao, and C. B. Thompson. 2001. IL-7 enhances the survival and maintains the size of naive T cells. J. Immunol. 167:6869-6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribeiro-Rodrigues, R., T. Resende Co, R. Rojas, Z. Toossi, R. Dietze, W. H. Boom, E. Maciel, and C. S. Hirsch. 2006. A role for CD4+CD25+ T cells in regulation of the immune response during human tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 144:25-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg, S. A., C. Sportès, M. Ahmadzadeh, T. J. Fry, L. T. Ngo, S. L. Schwarz, M. Stetler-Stevenson, K. E. Morton, S. A. Mavroukakis, M. Morre, R. Buffet, C. L. Mackall, and R. E. Gress. 2006. IL-7 administration to humans leads to expansion of CD8+ and CD4+ cells but a relative decrease of CD4+ T-regulatory cells. J. Immunother. 29:313-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scarpellini, P., S. Tasca, L. Galli, A. Beretta, A. Lazzarin, and C. Fortis. 2004. Selected pool of peptides from ESAT-6 and CFP-10 proteins for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3469-3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scripture-Adams, D. D., D. G. Brooks, Y. D. Korin, and J. A. Zack. 2002. Interleukin-7 induces expression of latent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with minimal effects on T-cell phenotype. J. Virol. 76:13077-13082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharp, E. R., J. D. Barbour, R. K. Karlsson, K. A. Jordan, J. K. Sandberg, A. Wiznia, M. G. Rosenberg, and D. F. Nixon. 2005. Higher frequency of HIV-1-specific T cell immune responses in African American children vertically infected with HIV-1. J. Infect. Dis. 192:1772-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42a.Soini, H., X. Pan, A. Amin, E. A. Graviss, A. Siddiqui, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from patients in Houston, Texas, by spoligotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:669-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sonnenberg, P., J. R. Glynn, K. Fielding, J. Murray, P. Godfrey-Faussett, and S. Shearer. 2005. How soon after infection with HIV does the risk of tuberculosis start to increase? A retrospective cohort study in South African gold miners. J. Infect. Dis. 191:150-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sportes, C., F. T. Hakim, S. A. Memon, H. Zhang, K. S. Chua, M. R. Brown, T. A. Fleisher, M. C. Krumlauf, R. R. Babb, C. K. Chow, T. J. Fry, J. Engels, R. Buffet, M. Morre, R. J. Amato, D. J. Venzon, R. Korngold, A. Pecora, R. E. Gress, and C. L. Mackall. 2008. Administration of rhIL-7 in humans increases in vivo TCR repertoire diversity by preferential expansion of naïve T cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 205:1701-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Subramanyam, S., L. E. Hanna, P. Venkatesan, K. Sankaran, P. R. Narayanan, and S. Swaminathan. 2004. HIV alters plasma and M. tuberculosis-induced cytokine production in patients with tuberculosis. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 24:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talayev, V. Y., I. Y. Zaichenko, O. N. Babaykina, M. A. Lomunova, E. B. Talayeva, and M. F. Nikonova. 2005. Ex vivo stimulation of cord blood mononuclear cells by dexamethasone and interleukin-7 results in the maturation of interferon-gamma-secreting effector memory T cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 141:440-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor, R. E. B., A. J. Cant, and J. E. Clark. 2008. Potential effect of NICE tuberculosis guidelines on pediatric tuberculosis screening. Arch. Dis. Child. 93:200-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vassena, L., M. Proschan, A. S. Fauci, and P. Lusso. 2007. Interleukin 7 reduces the levels of spontaneous apoptosis in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-infected individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:2355-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.