Abstract

The identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients is usually achieved by using phenotype-based techniques and eventually molecular tools. These techniques remain time-consuming, expensive, and technically demanding. We used a method based on matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) for the identification of these bacteria. A set of reference strains belonging to 58 species of clinically relevant nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli was used. To identify peaks discriminating between these various species, the profile of 10 isolated colonies obtained from 10 different passages was analyzed for each referenced strain. Conserved peaks with a relative intensity greater than 0.1 were retained. The spectra of 559 clinical isolates were then compared to that of each of the 58 reference strains as follows: 400 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 54 Achromobacter xylosoxidans, 32 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, 52 Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC), 1 Burkholderia gladioli, 14 Ralstonia mannitolilytica, 2 Ralstonia pickettii, 1 Bordetella hinzii, 1 Inquilinus limosus, 1 Cupriavidus respiraculi, and 1 Burkholderia thailandensis. Using this database, 549 strains were correctly identified. Nine BCC strains and one R. mannnitolilytica strain were identified as belonging to the appropriate genus but not the correct species. We subsequently engineered BCC- and Ralstonia-specific databases using additional reference strains. Using these databases, correct identification for these species increased from 83 to 98% and from 94 to 100% of cases, respectively. Altogether, these data demonstrate that, in CF patients, MALDI-TOF-MS is a powerful tool for rapid identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the main bacterial pathogen isolated from the sputa of patients suffering from cystic fibrosis (CF). Other nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli of clinical importance that can be isolated from this location include Achromobacter xylosoxidans, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, or species belonging to the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC). Recently, novel bacterial species have been isolated from CF patients as Ralstonia mannitolilytica (6, 10), Pandoraea apista (4, 22), and Inquilinus limosus (5, 25). Bacteria isolated during CF do not have the same virulence, thus pointing out the importance of bacterial identification by routine clinical microbiology laboratories for the management of CF patients. Moreover, the emergence of new bacterial species requires accurate identification tools in order to understand their clinical relevance and distribution in CF.

Conventional phenotypic methods and commercial kits are sometimes not suitable for strains isolated from CF patients. These pathogens often lack key phenotypic characters required for their identification (1, 10, 20, 23, 24, 26). In addition, in some circumstances, misidentification is due to the fact that the species are not in the database of commercial kits (10, 23). Molecular tools such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing provide reliable results (10, 16, 26). Other techniques, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (27) and amplified ribosomal DNA restriction assays, are available (22). Despite their good accuracy, these molecular techniques cannot be used routinely because they are expensive, time-consuming, and technically demanding.

Several studies have reported the use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) for bacterial identification (8, 9, 13-15, 17). MALDI-TOF-MS can examine the profile of proteins detected directly from intact bacteria. This technique, based on relative molecular masses, is a soft ionization method allowing desorption of peptides and proteins from whole different cultured microorganisms. Ions are separated and detected according to their molecular mass and charge. For a given bacterial strain, this approach yields a reproducible spectrum within minutes, consisting of a series of peaks corresponding to m/z ratios of ions released from bacterial proteins during laser desorption.

Recently, we engineered a strategy to identify bacteria belonging to the Micrococcaceae family (2). The aim of the present study is to extend this strategy to nonfermenting bacilli recovered from CF patients, thus opening the path toward rapid, accurate, and inexpensive bacterial identification in routine laboratories. Our first step was to build a complete database for all species belonging to the group of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli recovered from humans, including those isolated from CF patients. We then validated this database by using identification by MALDI-TOF-MS of clinical strains recovered from CF patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The reference strains used to engineer the MALDI-TOF-MS database belonged to 58 species of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli that can possibly be recovered from CF patients. Three databases were engineered, and the 87 strains used to complete these databases are described in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

TABLE 1.

Reference strains used to establish the MALDI-TOF-MS nonfermenting gram-negative bacillus database

| Species | Reference straina |

|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | CIP 76.110 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | CIP 69.13T |

| Pseudomonas mosselii | CIP 104061 |

| Pseudomonas putida | CIP 52.191T |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | CIP 103022T |

| Pseudomonas mendocina | CIP 75.21T |

| Pseudomonas alcaligenes | CIP 101034T |

| Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes | CIP 66.14T |

| Pseudomonas oryzihabitans | CIP 102996T |

| Pseudomonas luteola | CIP 102995T |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | CIP 60.77T |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans subsp. xylosoxidans | CIP 71.32T |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans subsp. denitrificans | CIP 77.15T |

| Achromobacter piechaudii | CIP 101223 |

| BCC | |

| Burkholderia cepacia | CIP 80.24T |

| Burkholderia multivorans | CIP 105495T |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | CIP 108255T |

| Burkholderia stabilis | CIP 106845T |

| Burkholderia vietnamiensis | CIP 105875T |

| Burkholderia dolosa | CIP 108406 |

| Burkholderia ambifaria | CIP 107266T |

| Burkholderia anthina | CIP 108228T |

| Burkholderia pyrrocinia | CIP 105874T |

| Burkholderia gladioli | CIP 105410T |

| Burkholderia cocovenenans | ATCC 33664 |

| Burkholderia glumae | NCPPB 2391 |

| Burkholderia plantarii | ATCC 43733 |

| Burkholderia thailandensis | LMG 20219 |

| Burkholderia glathei | CIP 105421T |

| Burkholderia andropogonis | ATCC 23060 |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica | CIP 107281T |

| Ralstonia pickettii | CIP 73.23T |

| Cupriavidus gilardii | CIP 105966T |

| Cupriavidus pauculus | CIP 105943T |

| Cupriavidus respiraculi | LMG 21509 |

| Bordetella avium | CIP 103348T |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | CIP 55.110T |

| Bordetella hinzii | CIP 104527T |

| Alcaligenes faecalis subsp. faecalis | CIP 60.80T |

| Aeromonas sobria | CIP 74.33T |

| Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. hydrophila | CIP 76.14T |

| Aeromonas veronii | CIP 103438T |

| Aeromonas caviae | CIP 76.16T |

| Delftia acidovorans | CIP 103021T |

| Shewanella putrefaciens | CIP 80.40T |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | CIP 63.5T |

| Chryseobacterium indologenes | CIP 101026T |

| Elizabethkingia meningoseptica | CIP 60.57T |

| Sphingobacterium multivorum | CIP 100541T |

| Sphingobacterium spiritivorum | CIP 100542T |

| Brevundimonas diminuta | CIP 63.27T |

| Brevundimonas vesicularis | CIP 101035T |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis | CIP 100752T |

| Inquilinus limosus | CIP 108342T |

| Pandoraea apista | CIP 106627T |

| Pandoraea norimbergensis | LMG 13019 |

| Pandoraea promenusa | LMG 18087 |

| Pandoraea pulmonicola | LMG 18106 |

| Pandoraea sputorum | LMG 18100 |

CIP, Collection de l'Institut Pasteur (Paris, France); NCPPB, National Collection of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria (York, United Kingdom); LMG, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie Bacteriënverzameling (Ghent, Belgium). T, “type” strain of the species.

TABLE 2.

Reference strains used to establish the MALDI-TOF-MS BCC database

| Species | Reference straina |

|---|---|

| Burkholderia cepacia | CIP 80.24T |

| Burkholderia cepacia | LMG 6889 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | LMG 2161 |

| Burkholderia multivorans | CIP 105495T |

| Burkholderia multivorans | LMG 14273 |

| Burkholderia multivorans | LMG 14293 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | CIP 108255T |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | LMG 18863 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | LMG 21440 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | LMG 18829 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | LMG 18830 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | LMG 19230 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | LMG 19240 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | LMG 21462 |

| Burkholderia stabilis | CIP 106845T |

| Burkholderia stabilis | LMG 6997 |

| Burkholderia stabilis | LMG 7000 |

| Burkholderia vietnamiensis | CIP 105875T |

| Burkholderia vietnamiensis | LMG 6998 |

| Burkholderia vietnamiensis | LMG 6999 |

| Burkholderia dolosa | CIP 108406 |

| Burkholderia dolosa | LMG 18941 |

| Burkholderia ambifaria | CIP 107266T |

| Burkholderia ambifaria | LMG 11351 |

| Burkholderia ambifaria | LMG 17828 |

| Burkholderia anthina | CIP 108228T |

| Burkholderia anthina | LMG 16670 |

| Burkholderia pyrrocinia | CIP 105874T |

| Burkholderia pyrrocinia | LMG 21822 |

| Burkholderia pyrrocinia | LMG 21823 |

CIP, Collection de l'Institut Pasteur (Paris, France); LMG, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie Bacteriënverzameling (Ghent, Belgium). T, “type” strain of the species.

TABLE 3.

Reference strains used to establish the MALDI-TOF-MS Ralstonia database

| Species | Reference straina |

|---|---|

| Cupriavidus gilardii | CIP 105966T |

| Cupriavidus gilardii | LMG 3399 |

| Cupriavidus gilardii | LMG 3400 |

| Cupriavidus pauculus | CIP 105943T |

| Cupriavidus pauculus | LMG 3245 |

| Cupriavidus pauculus | LMG 3317 |

| Cupriavidus respiraculi | LMG 21509 |

| Cupriavidus respiraculi | LMG 21510 |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica | CIP 107281T |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica | LMG 18098 |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica | LMG 18102 |

| Ralstonia pickettii | CIP 73.23T |

| Ralstonia pickettii | LMG 5942 |

| Ralstonia pickettii | LMG 7001 |

CIP, Collection de l'Institut Pasteur (Paris, France); LMG, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie Bacteriënverzameling (Ghent, Belgium). T, “type” strain of the species.

The tested strains used to validate the databases were as follows.

(i) A total of 512 clinical isolates of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli were recovered from the sputum samples of children with CF attending the pediatric department of the Necker-Enfants Malades hospital (Paris, France) between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2006: 400 P. aeruginosa strains (101 patients), 54 Achromobacter xylosoxidans strains (12 patients), 32 S. maltophilia strains (12 patients), 9 R. mannitolilytica strains (1 patient), 14 BCC strains (2 patients), 1 Burkholderia gladioli strain, 1 Bordetella hinzii strain, and 1 I. limosus strain. These strains were identified by phenotypic tests or molecular methods as previously described (10). Briefly, isolates displaying green or yellow-green pigmentation, a positive oxidase test, growth at 42°C, growth on cetrimide agar, and susceptibility to colimycin (disk diffusion method) were identified as P. aeruginosa. Isolates that did not express these criteria were identified by using the API 20NE system (bioMerieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France). The results of the API 20NE tests were interpreted by using the APILAB Plus software package (bioMerieux). When the API 20NE system did not identify a P. aeruginosa, A. xylosoxidans, or S. maltophilia strain, the identification was further pursued by sequencing an internal fragment of the 16Sr RNA gene as previously described (10). A total of 16 of the 400 P. aeruginosa strains and 26 of the 112 non-P. aeruginosa strains required molecular methods for identification. B. cepacia strains were identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Identification was confirmed by the Observatoire National des Cepacia using amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis (ARDRA) (21, 22). Species-specific recA PCR and/or B. cepacia complex-recA restriction analysis was used to circumvent the limitations of ARDRA within the B. cepacia complex (19).

(ii) A total of 47 clinical strains were obtained from the Observatoire National des Cepacia (Toulouse, France): 38 BCC strains (11 Burkholderia vietnamiensis strains, 10 Burkholderia multivorans strains, 8 B. cenocepacia strains, 5 Burkholderia stabilis strains, 1 Burkholderia dolosa strain, 1 Burkholderia pyrrocinia strain, and 2 B. cepacia strains), 1 Burkholderia thailandensis strain, 5 R. mannitolilytica strains, 2 Ralstonia pickettii strains, and 1 Cupriavidus respiraculi strain.

All bacterial strains used in the study were stored at −80°C in Trypticase soy broth supplemented with 15% glycerol.

MALDI-TOF-MS.

The strains were grown on Mueller-Hinton agar and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Most of the isolates grew after 24 h but some strains that did not grow after 24 h were further incubated for 48 h or 72 h. An isolated colony was harvested in 20 μl of sterile water. A 1-μl portion of this mixture was deposited on a target plate (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in two replicates and allowed to dry at room temperature. Then, 1 μl of absolute ethanol was added to each well, and the mixture allowed to dry. Next, 1 μl of matrix solution DHB (2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid, 50 mg/ml; 30% acetonitrile; 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) was added and allowed to cocrystallize with the sample. Samples were processed in the MALDI-TOF-MS spectrometer (Autoflex; Bruker Daltonics) with the flex control software (Bruker Daltonics). Positive ions were extracted with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV in linear mode. Each spectrum was the sum of the ions obtained from 200 laser shots performed in five different regions of the same well. The spectra have been analyzed in an m/z range of 2,000 to 20,000. The analysis was performed with the flex analysis software and calibrated with protein calibration standard I (Bruker Daltonics). The data obtained with the two replicates were added to minimize the random effect. The presence or absence of peaks was considered a fingerprint for a particular isolate. The profiles were analyzed and compared by using the newly developed software BGP database (http://sourceforge.net/projects/bgp). Numeric data obtained from the spectrometer acquisition software (peak value and relative intensity for each peak) are sent to the BGP software. This software identifies the number of common peaks between the spectra of the tested strain and each set of peaks specific of a reference strain contained in the database (i.e., the nonfermenting gram-negative bacillus database). The software determines a percentage for each reference strain (100 × the number of common peaks between the tested strain and the peaks specific for one reference strain/the total number of peaks specific for one reference strain). The identification of the tested strain corresponds to the species of the reference strain with the best match in the database. The greater the difference between the first and second matches, the better the discrimination between species. A difference of at least 10% is required to obtain a good identification.

RESULTS

Engineering of the nonfermenting gram-negative bacillus database.

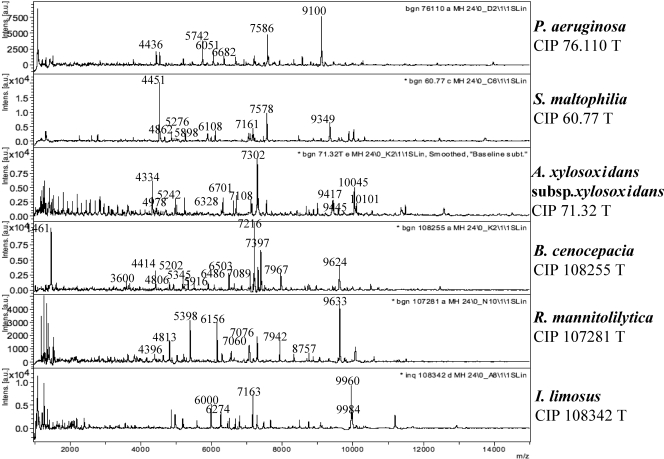

The database was engineered using a previously described strategy (2). A set of reference strains has been selected as belonging to clinically relevant nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli, including those representative of the species routinely recovered from CF patients (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the spectrum obtained with six species of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli. Ten isolates of each of these selected strains grown on Mueller-Hinton 24H were analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS as described in Materials and Methods. For each strain, we retained only the peaks with a relative intensity greater than 0.1 that were constantly present in all 10 sets of data obtained for a given strain. The standard deviation for each conserved peak did not exceed 6 m/z value. Table 4 shows the m/z values of the selected peaks that have been retained for eight reference strains. The set of peaks was specific for each selected strain.

FIG. 1.

MALDI-TOF-MS spectra of six reference strains.

TABLE 4.

m/z values of the selected peaks of eight species of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli

| Strain | m/z values (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans subsp. xylosoxidans CIP 71.32T | 2,190 ± 1, 2,319 ± 1, 2,447 ± 1, 2,576 ± 1, 2,705 ± 1, 2,833 ± 1, 2,865 ± 1, 2,962 ± 1, 4,334 ± 2, 4,978 ± 2, 5,018 ± 1, 5,242 ± 2, 6,328 ± 2, 6,626 ± 1, 6,701 ± 2, 7,108 ± 1, 7,302 ± 1, 8,681 ± 2, 9,417 ± 2, 9,445 ± 2, 10,045 ± 2, 10,101 ± 2 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa CIP 76.110 | 4,436 ± 2, 4,544 ± 3, 5,213 ± 3, 5,742 ± 3, 6,051 ± 3, 6,353 ± 3, 6,682 ± 4, 6,918 ± 4, 7,211 ± 4, 7,586 ± 4, 7,621 ± 4, 8,575 ± 5, 9,100 ± 5 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens CIP 69.13T | 4,339 ± 1, 6,089 ± 1, 6,275 ± 2, 6,403 ± 1, 6,634 ± 2, 7,182 ± 1, 7,604 ± 2, 7,647 ± 1, 9,568 ± 1 |

| Pseudomonas putida CIP 52.191T | 3,810 ± 1, 4,439 ± 1, 4,473 ± 1, 5,145 ± 1, 6,000 ± 2, 6,345 ± 2, 6,679 ± 2, 7,553 ± 2, 7,635 ± 2, 8,395 ± 2, 8,637 ± 2, 9,147 ± 3, 9,561 ± 3 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia CIP 108255T | 3,600 ± 2, 4,414 ± 2, 4,806 ± 2, 5,202 ± 2, 5,345 ± 2, 5,916 ± 3, 6,486 ± 3, 6,503 ± 4, 7,089 ± 3, 7,216 ± 3, 7,318 ± 3, 7,397 ± 3, 7,967 ± 3, 9,624 ± 4 |

| Burkholderia gladioli CIP 105410T | 4,416 ± 1, 4,808 ± 1, 5,204 ± 1, 5,225 ± 3, 6,305 ± 1, 6,489 ± 2, 6,597 ± 1, 6,859 ± 2, 6,959 ± 2, 7,060 ± 2, 7,105 ± 2, 7,185 ± 2, 7,217 ± 3, 7,325 ± 2, 7,673 ± 1, 7,794 ± 2, 8,737 ± 2, 9,627 ± 2, 10,458 ± 4 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia CIP 60.77T | 4,541 ± 1, 4,862 ± 1, 5,276 ± 1, 5,898 ± 3, 6,108 ± 1, 7,161 ± 2, 7,578 ± 2, 9,349 ± 2 |

| Ralstonia mannitolilytica CIP 107281T | 3,818 ± 3, 4,396 ± 1, 4,813 ± 4, 5,398 ± 4, 6,156 ± 4, 7,060 ± 5, 7,060 ± 5, 7,078 ± 5, 7,943 ± 4, 9,632 ± 4 |

We next sought to determine whether this database could be used for the identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli, thus demonstrating that the set of peaks for each selected strain is, at least partially, conserved among isolates of the same species. The database was tested using the set of strains described in Materials and Methods. For each isolate, all peaks with an intensity of ≥0.02 were retained and were compared to the intensities of the specific peaks of each reference strain included in the database by using the BGP database software, taking into account a possible error of ±10 m/z value. Table 5 presents the findings for one P. aeruginosa strain. We next determined for all tested strains the percentage of common peaks obtained with each of the reference strains. Only the first and second best matches were retained (Table 6). We considered a difference ≥10% as the minimum required to give a correct identification. A correct identification was obtained for all strains except those belonging to the BCC and the Ralstonia genus (Table 6). The latter were identified as belonging to the BCC or the Ralstonia genus, but the species identification was not correct.

TABLE 5.

Identification of a P. aeruginosa strain using the BGP softwarea

| Profile name (match) |

m/z value

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Isolate 06178603 | Database | |

| P. aeruginosa (13/13)b | 4441 | 4436 |

| 4548 | 4544 | |

| 5216 | 5213 | |

| 5743 | 5742 | |

| 6053 | 6051 | |

| 6354 | 6353 | |

| 6682 | 6682 | |

| 6917 | 6918 | |

| 7209 | 7211 | |

| 7584 | 7586 | |

| 7620 | 7621 | |

| 8571 | 8575 | |

| 9096 | 9100 | |

| F. oryzihabitans (7/12)c | 4441 | 4435 |

| 6053 | 6053 | |

| 6505 | 6503 | |

| 6682 | 6680 | |

| 7497 | 7498 | |

| 7584 | 7581 | |

| 9123 | 9126 | |

The best match was obtained with the P. aeruginosa reference strain. The second best match was with F. oryzihabitans.

The 13 peaks obtained for the tested isolate matched all 13 peaks of the P. aeruginosa isolate.

The 7 peaks obtained for the tested isolate matched 7 of 12 peaks of the F. oryzihabitans database.

TABLE 6.

Identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli by MALDI-TOF-MS

| Species | No. of strains tested | Avg % of common peaks (best match)a | No. of strains correctly identifiedb | Avg % of common peaks (second best match)c | No. of strains (<10% difference)d | No. of strains (correct identification)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | 400 | 87 (38-100) | 400 | 51 (18-83) | 1‡ | |

| A. xylosoxidans | 54 | 89 (59-100) | 54 | 73 (50-88) | 2‡ (2nd choice: A. piechaudii) | |

| S. maltophilia | 32 | 82 (63-100) | 32 | 45 (29-67) | 0 | |

| B. cenocepacia | 22 | 82 (57-100) | 18‡ | 70 (56-86) | 7 | 22 |

| B. vietnamiensis | 11 | 83 (68-100) | 9* | 59 (67-81) | 4 | 11 |

| B. multivorans | 10 | 63 (92-100) | 9* | 53 (74-87) | 0 | 9 |

| B. stabilis | 5 | 72 (67-80) | 4* | 64 (56-69) | 2 | 5 |

| B. cepacia | 2 | 88 (81-94) | 2 | 62 (59-64) | 0 | 2 |

| B. pyrrocina | 1 | 94 | 1 | 67 | 0 | 1 |

| B. dolosa | 1 | 63 | 0* | 60 | 1 | 0f |

| R. mannitolilytica | 14 | 79 (70-80) | 13† | 66 (56-70) | 4 | 14 |

| R. pickettii | 2 | 73 (70-80) | 2 | 58 (42-75) | 0 | 2 |

| C. respiraculi | 1 | 56 | 1 | 43 | 0 | |

| B. gladioli | 1 | 82 | 1 | 64 | 0 | |

| B. hinzii | 1 | 90 | 1 | 56 | 0 | |

| I. limosus | 1 | 60 | 1 | 25 | 0 | |

| B. thailandensis | 1 | 85 | 1 | 73 | 0 |

That is, the average percentage of common peaks between the tested strain and the best match of the general database(ranges are indicated in parentheses).

That is, the number of strains for which the best match is the correct identification. *, the misidentified strain was identified as B. cepacia; †, the misidentified strain was identified as R. pickettii; ‡, the four misidentified strains were identified as three B. cepacia strains and one B. cocovenenans strain.

That is, the average percentage of common peaks between the tested strain and the second best match of the general database(ranges are indicated in parentheses).

That is, the number of strains for which the difference of common peaks between the best and second-best matches is less than 10%. ‡, These strains were retested, and the second set of data provided the same identification as the initial one.

That is, the number of strains for which the identification is correct using the BCC or Ralstonia database.

The misidentified strain was identified as B. multivorans.

Engineering of specific databases.

In order to improve the identification of strains belonging to the BCC and the Ralstonia genus, we engineered BCC and Ralstonia specific databases. We hypothesized that including several reference strains for one given genospecies would improve identification of the tested strains.

The BCC specific database encompassed the 9 BCC reference strains used to engineer the nonfermenting gram-negative bacillus database and an additional 21 BCC reference strains provided by the LMG bacterial collection (Table 2), so that each species was represented by several reference strains. For each of these reference strains, only peaks with a relative intensity greater than 0.1 that were constantly present in all 10 sets of data were retained. However, in order to increase the ability of this database to discriminate between the species, only peaks that were constantly conserved in all reference strains of the same species were retained in the database.

This BCC specific database was then tested using all clinical strains belonging to the BCC. This approach improved the differentiation between BCC species: only one B. dolosa strain was falsely identified as B. multivorans. Six B. cenocepacia strains could not be differentiated from B. cepacia. However, we noticed that a peak (m/z 7,546) was constantly present in B. cepacia strains and constantly absent in B. cenocepacia. On the basis of this peak, a correct identification was obtained for all B. cenocepacia strains.

The same strategy as that used for BCC database was thus applied to engineer a specific Ralstonia database, using supplementary reference strains provided by the LMG bacterial collection (Table 3). This new database allowed the correct identification of all strains.

DISCUSSION

The bacterial species responsible for infection in CF patients do not display the same pathogenicity and thus do not require the same clinical management, thus pointing out the need for a correct and rapid identification of the bacteria isolated. The present study demonstrates that the strategy described here is suitable for accurate species identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated in CF. Indeed, all CF P. aeruginosa strains were accurately identified. Prior to the present study, we have tested 12 strains belonging to four species (P. aeruginosa, A. xylosoxidans, B. cenocepacia, and S. maltophilia) using three different media (Mueller-Hinton, chocolate agar, and blood agar) and two culture periods (18 and 24 h). Identifications were the same regardless of the media used to grow the bacteria (data not shown). Furthermore, the spectra were similar after 18 or 24 H of growth. In addition, identification was not affected if the strain grew only after 48 h of incubation. The mucoid character of the strains recovered from patients with chronic colonization is frequently an obstacle to accurate identification using biochemical tests. Nevertheless, none of the mucoid strains in our study was misidentified. Only one mucoid strain had a low percentage of matches with the P. aeruginosa reference strain (38%), but the MALDI-TOF-MS identification was correct since the profile gave 22% of matches with the second choice. All S. maltophilia and A. xylosoxidans were correctly identified. It should be pointed out that frequent misidentification occurs between these species and BCC strains (20).

Infection by BCC species in CF patients has been shown to increase morbidity and premature mortality (7, 18) and may represent a contraindication to lung transplantation (12). Furthermore, the risk associated with dissemination of B. cenocepacia strains requires specific means in order to prevent the bacterial spread (11). The rapid identification of B. cenocepacia using the BCC database allows the immediate implementation of a specific clinical management before obtaining the results of molecular identification.

Despite the good results achieved for BCC strains, the wrong identification obtained for one strain points out the need of a larger set of clinical strains to improve the identification of BCC species.

R. mannitolilytica, I. limosus, B. hinzii, and B. gladioli were correctly identified by MALDI-TOF-MS. Of note, the strain identified as B. gladioli matched also with the reference strain of B. cocovenenans (data not shown), a bacterial species that has been shown to be a junior synonym of B. gladioli (3). Conventional identification is not reliable for this species, as well as for other species, such as R. mannitolilytica or I. limosus isolated during our study. API 20NE gave a very good identification of I. limosus as Sphingomonas paucimobilis, as previously described, which can thus lead to an underestimation of this emerging pathogen (25). The bacteria that are rarely isolated in CF patients can then be accurately identified using our database, since we make sure that the database is as complete as possible using many reference strains, even strains belonging to species rarely isolated from CF patients. In our experience, all strains included in the database would have allowed identification of 100% of the nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from the CF patients in our hospital.

Emerging new bacterial species will give a spectrum that does not match any of the reference spectra contained in the database. However, tested strains for which identification is not obtained by MALDI-TOF-MS can be identified by using a molecular biology approach, thus improving rapidly the database with new species. Such a rapid improvement is usually not achievable using biochemical kits. Moreover, when two bacterial cultures are mixed, the global spectrum results is the sum of the two spectra, with specific peaks for both.

Actually, MALDI-TOF-MS bacterial identification is a phenotypic method, but analysis of the origin of the ions detected in the spectra shows that the majority of the peaks correspond to ribosomal proteins (8), which are proteins that represent a great proportion of the whole bacterial proteome and that are constantly expressed and conserved in bacteria. Metabolic characters lack specificity since the result can either be positive or negative and many biochemical tests correspond to universal metabolic pathways that can be common to several bacteria.

A laboratory technician, without background in spectrometry, can easily use this method. After the sample and matrix are deposited as described in Materials and Methods, the spectrometer can be programmed so that the laser impacts automatically over the entire surface of the matrix, and there is no human intervention on the software for the species identification. The calibration with the standard and the treatment of data (selection of peaks with relative intensity of ≥0.02 and calculation of peaks ratios between database and tested strains by the BGP software) are automatically processed. Therefore, this is very basic software which does not require any expertise or subjective process and can be easily performed even with an inexperienced operator. The time required to run 50 samples is about 1 h.

Altogether, these data show that bacterial identification by MALDI-TOF-MS may improve the clinical management of CF patients. Since this is a very low-cost technique (about 0.9 euro/50 samples), it is likely that, considering the speed with which reliable identification can be obtained, this technique may ultimately replace routine phenotypic assays.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gilles Quesnes and Eric Frapy for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brisse, S., S. Stefani, J. Verhoef, A. Van Belkum, P. Vandamme, and W. Goessens. 2002. Comparative evaluation of the BD Phoenix and VITEK 2 automated instruments for identification of isolates of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 401743-1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbonnelle, E., J. L. Beretti, S. Cottyn, G. Quesne, P. Berche, X. Nassif, and A. Ferroni. 2007. Rapid identification of staphylococci isolated in clinical microbiology laboratories by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 452156-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coenye, T., B. Holmes, K. Kersters, J. R. Govan, and P. Vandamme. 1999. Burkholderia cocovenenans (van Damme et al. 1960) Gillis et al. 1995 and Burkholderia vandii Urakami et al. 1994 are junior synonyms of Burkholderia gladioli (Severini 1913) Yabuuchi et al. 1993 and Burkholderia plantarii (Azegami et al. 1987) Urakami et al. 1994, respectively. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 4937-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coenye, T., L. Liu, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2001. Identification of Pandoraea species by 16S ribosomal DNA-based PCR assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 394452-4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coenye, T., J. Goris, T. Spilker, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2002. Characterization of unusual bacteria isolated from respiratory secretions of cystic fibrosis patients and description of Inquilinus limosus gen. nov., sp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402062-2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coenye, T., P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2002. Infection by Ralstonia species in cystic fibrosis patients: identification of Ralstonia pickettii and R. mannitolilytica by polymerase chain reaction. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8692-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corey, M., and V. Farewell. 1996. Determinants of mortality from cystic fibrosis in Canada, 1970-1989. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1431007-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demirev, P. A., Y. P. Ho, V. Ryzhov, and C. Fenselau. 1999. Microorganism identification by mass spectrometry and protein database searches. Anal. Chem. 712732-2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenselau, C., and P. A. Demirev. 2001. Characterization of intact microorganisms by MALDI mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 20157-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferroni, A., I. Sermet-Gaudelus, E. Abachin, G. Quesne, G. Lenoir, P. Berche, and J. L. Gaillard. 2002. Use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli recovered from patients attending a single cystic fibrosis center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 403793-3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Govan, J. R., P. H. Brown, J. Maddison, C. J. Doherty, J. W. Nelson, M. Dodd, A. P. Greening, and A. K. Webb. 1993. Evidence for transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia by social contact in cystic fibrosis. Lancet 34215-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadjiliadis, D. 2007. Special considerations for patients with cystic fibrosis undergoing lung transplantation. Chest 1311224-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland, R. D., C. R. Duffy, F. Rafii, J. B. Sutherland, T. M. Heinze, C. L. Holder, K. J. Voorhees, and J. O. Lay, Jr. 1999. Identification of bacterial proteins observed in MALDI TOF mass spectra from whole cells. Anal. Chem. 713226-3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland, R. D., J. G. Wilkes, F. Rafii, J. B. Sutherland, C. C. Persons, K. J. Voorhees, and J. O. Lay, Jr. 1996. Rapid identification of intact whole bacteria based on spectral patterns using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 101227-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnamurthy, T., and P. L. Ross. 1996. Rapid identification of bacteria by direct matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometric analysis of whole cells. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 101992-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambiase, A., V. Raia, M. Del Pezzo, A. Sepe, V. Carnovale, and F. Rossano. 2006. Microbiology of airway disease in a cohort of patients with cystic fibrosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lay, J. O., Jr. 2001. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of bacteria. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 20172-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipuma, J. J. 2005. Update on the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 11528-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahenthiralingam, E., J. Bischof, S. Byrne, C. Radomski, J. Davies, Y. Av-Gay, and P. Vandamme. 2000. DNA-based diagnostic approaches for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex, Burkholderia vietnamiensis, Burkholderia multivorans, Burkholderia stabilis, and Burkholderia cepacia genomovars I and III. J. Clin. Microbiol. 383165-3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMenamin, J. D., T. M. Zaccone, T. Coenye, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2000. Misidentification of Burkholderia cepacia in US cystic fibrosis treatment centers: an analysis of 1,051 recent sputum isolates. Chest 1171661-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segonds, C., T. Heulin, N. Marty, and G. Chabanon. 1999. Differentiation of Burkholderia species by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the 16S rRNA gene and application to cystic fibrosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 372201-2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segonds, C., S. Paute, and G. Chabanon. 2003. Use of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis for identification of Ralstonia and Pandoraea species: interest in determination of the respiratory bacterial flora in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413415-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shelly, D. B., T. Spilker, E. J. Gracely, T. Coenye, P. Vandamme, and J. J. LiPuma. 2000. Utility of commercial systems for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex from cystic fibrosis sputum culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 383112-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Pelt, C., C. M. Verduin, W. H. Goessens, M. C. Vos, B. Tummler, C. Segonds, F. Reubsaet, H. Verbrugh, and A. van Belkum. 1999. Identification of Burkholderia spp. in the clinical microbiology laboratory: comparison of conventional and molecular methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 372158-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wellinghausen, N., A. Essig, and O. Sommerburg. 2005. Inquilinus limosus in patients with cystic fibrosis, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11457-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wellinghausen, N., J. Kothe, B. Wirths, A. Sigge, and S. Poppert. 2005. Superiority of molecular techniques for identification of gram-negative, oxidase-positive rods, including morphologically nontypical Pseudomonas aeruginosa, from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 434070-4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wellinghausen, N., B. Wirths, and S. Poppert. 2006. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for rapid identification of Achromobacter xylosoxydans and Alcaligenes faecalis recovered from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 443415-3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]