Abstract

An evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay (Bruce-ladder) was performed in seven laboratories using 625 Brucella strains from different animal and geographical origins. This robust test can differentiate in a single step all of the classical Brucella species, including those found in marine mammals and the S19, RB51, and Rev.1 vaccine strains.

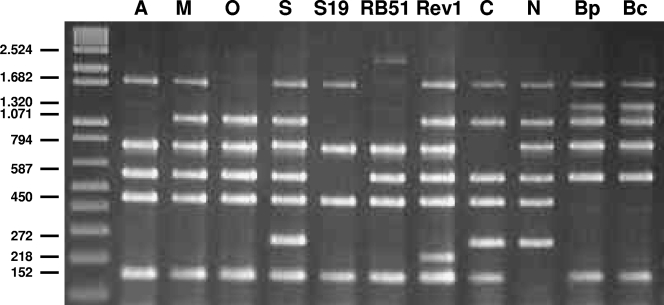

Brucellosis is caused by a facultative intracellular bacterium of the genus Brucella, and it is one of the most frequent bacterial zoonoses in low-income countries, where the control programs have not succeeded in eradicating this neglected zoonosis. The disease is a major cause of direct economic losses and an impediment to trade and exportation. The genus Brucella consists of six recognized species, designated on the basis of differences in pathogenicity and host preference: B. melitensis (goats and sheep), B. abortus (cattle and bison), B. suis (infecting primarily swine but also hares, rodents, and reindeer), B. ovis (sheep), B. canis (dogs), and B. neotomae (wood rats) (7). The discovery of Brucella in a wide variety of marine mammals has led to the proposal of two new species: B. ceti (cetaceans) and B. pinnipedialis (pinnipeds) (8). Some of these species include several biovars, which are currently distinguished from each other by an analysis of approximately 25 phenotypic characteristics, including requirement for CO2, H2S production, sensitivity to dyes and phages, and other metabolic properties (1). However, all these tests are time-consuming, require skilled technicians, and are not straightforward, and some reagents are not commercially available. In addition, handling of this microorganism represents a high risk for laboratory personnel, since most Brucella strains are highly pathogenic for humans. Accurate diagnostic and typing procedures are critical for the success of the eradication and control of the disease, and therefore the identification of the different species is of great epidemiological importance. In order to overcome most of these difficulties, PCR-based assays have been employed for molecular typing of Brucella species. However, one of the challenges of using DNA-based techniques for differentiating the various Brucella species and strains is their high degree of genetic homology (16). This article describes the evaluation of a new multiplex PCR assay (10), named Bruce-ladder, in seven different European laboratories. The PCR protocol was standardized previously (10), and the same protocol was used in all laboratories (see the supplemental material). The selection of the DNA sequences to design the PCR primers was based on species-specific or strain-specific genetic differences (Table 1). Each laboratory used its own Brucella strain collection, typed by standard bacteriological procedures (1). A total of 625 Brucella strains were used (see the complete list in the supplemental material). The collection included the reference strains of all biovars of B. abortus, B. melitensis, B. suis, and B. ovis, B. canis, B. neotomae, the B. abortus S19, B. abortus RB51, and B. melitensis Rev.1 vaccine strains, and the recently proposed B. pinnipedialis and B. ceti (8). To ensure adequate diversity, isolates from different geographic origins and different animal species, including humans, were selected (Table 2). Genomic DNA was extracted from pure cultures by using standard microbial DNA isolation kits or by heat lysis of bacterial cell cultures. Bruce-ladder identification was based on the numbers and sizes of seven products amplified by PCR. A representative example of the multiplex PCR result is presented in Fig. 1. PCR using DNA from B. abortus strains amplified five fragments, of 1,682, 794, 587, 450, and 152 bp in size; with B. melitensis DNA, an additional 1,071-bp fragment was amplified; and B. ovis was distinguished by the absence of the 1,682-bp fragment and B. suis by the presence of an additional 272-bp fragment (also present in B. canis and B. neotomae). PCR with B. abortus S19 DNA did not produce the 587-bp fragment common to all Brucella strains tested, and B. abortus RB51 was readily distinguished by the absence of the 1,682-bp and 1,320-bp fragments and by a specific additional 2,524-bp fragment. The B. melitensis Rev.1 vaccine strain was readily distinguished from other B. melitensis strains by a specific additional 218-bp fragment. B. canis was distinguished by the absence of the 794-bp fragment and B. neotomae by the absence of the 152-bp fragment. Finally, when DNA from Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals (B. pinnipedialis and B. ceti) was used, a specific additional 1,320-bp fragment was amplified whereas the 450-bp fragment was absent. The same results presented in Fig. 1 were obtained with all Brucella strains assayed, with the only exception being some B. canis strains. Nine out of 21 B. canis strains showed the same PCR profile as B. suis. Typing of these nine strains was confirmed by classical typing and multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (data not shown). Interestingly, these B. canis strains with a B. suis-like profile were resistant to basic fuchsin and safranin (a variant of the classical B. canis phenotypic pattern). However, these findings do not detract from the utility of the Bruce-ladder PCR, since it is very simple, using sensitivity to dyes and phage susceptibility to differentiate B. canis (a rough species) from B. suis (a smooth species). In addition, B. canis is always isolated from dogs, and B. suis has never been found in this host.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in Bruce-ladder multiplex PCR assay

| Primera | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | DNA target | Source of genetic differences | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMEI0998f | ATC CTA TTG CCC CGA TAA GG | 1,682 | Glycosyltransferase, gene wboA | IS711 insertion in BMEI0998 in B. abortus RB51 and deletion of 15,079 bp in BMEI0993-BMEI1012 in B. ovis | 9, 15 |

| BMEI0997r | GCT TCG CAT TTT CAC TGT AGC | ||||

| BMEI0535f | GCG CAT TCT TCG GTT ATG AA | 450 (1,320)b | Immunodominant antigen, gene bp26 | IS711 insertion in BMEI0535-BMEI0536 in Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals | 5 |

| BMEI0536r | CGC AGG CGA AAA CAG CTA TAA | ||||

| BMEII0843f | TTT ACA CAG GCA ATC CAG CA | 1,071 | Outer membrane protein, gene omp31 | Deletion of 25,061 bp in BMEII826-BMEII0850 in B. abortus | 17 |

| BMEII0844r | GCG TCC AGT TGT TGT TGA TG | ||||

| BMEI1436f | ACG CAG ACG ACC TTC GGT AT | 794 | Polysaccharide deacetylase | Deletion of 976 bp in BMEI1435 in B. canis | 13 |

| BMEI1435r | TTT ATC CAT CGC CCT GTC AC | ||||

| BMEII0428f | GCC GCT ATT ATG TGG ACT GG | 587 | Erythritol catabolism, gene eryC (d-erythrulose-1-phosphate dehydrogenase) | Deletion of 702 bp in BMEII0427-BMEII0428 in B. abortus S19 | 14 |

| BMEII0428r | AAT GAC TTC ACG GTC GTT CG | ||||

| BR0953f | GGA ACA CTA CGC CAC CTT GT | 272 | ABC transporter binding protein | Deletion of 2,653 bp in BR0951-BR0955 in B. melitensis and B. abortus | 11, 12 |

| BR0953r | GAT GGA GCA AAC GCT GAA G | ||||

| BMEI0752f | CAG GCA AAC CCT CAG AAG C | 218 | Ribosomal protein S12, gene rpsL | Point mutation in BMEI0752 in B. melitensis Rev.1 | 6 |

| BMEI0752r | GAT GTG GTA ACG CAC ACC AA | ||||

| BMEII0987f | CGC AGA CAG TGA CCA TCA AA | 152 | Transcriptional regulator, CRP family | Deletion of 2,203 bp in BMEII0986-BMEII0988 in B. neotomae | 13 |

| BMEII0987r | GTA TTC AGC CCC CGT TAC CT |

Designation are based on the B. melitensis (BME) or B. suis (BR) genome sequences. f, forward; r, reverse.

Due to a DNA insertion in the bp26 gene, the amplicon size in Brucella strains isolated from marine mammals is 1,320 bp.

TABLE 2.

Hosts and geographic origins of the 625 Brucella strains tested by Bruce-ladder PCR

| Species | Biovar | Host(s) | Origin | No. of strains tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. abortus | 1 | Cattle, buffalo, humans | Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, Brazil, USA,a Algeria | 39 |

| 2 | Cattle | Costa Rica. Greece | 3 | |

| 3 | Cattle, humans, sheep | Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, Greece | 40 | |

| 4 | Cattle | France, Italy, Equator | 14 | |

| 5 | 1 | |||

| 6 | Cattle | France | 3 | |

| 7 | Cattle | Mongolia, Turkey | 2 | |

| 9 | Cattle | Belgium, France | 7 | |

| B. melitensis | 1 | Sheep, goats, cattle, humans | Spain, Portugal, Belgium, USA, Mexico | 45 |

| 2 | Humans, goat, cattle | Spain, Turkey, Lebanon | 8 | |

| 3 | Sheep, goats, cattle, humans, swine, chamois | Spain, Portugal, France, Belgium, Morocco, Croatia | 163 | |

| B. suis | 1 | Wild boars, swine, hares, humans | Croatia, China, United Kingdom, Portugal, France, French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna islands | 25 |

| 2 | Wild boars, swine, hares, humans, cattle | Spain, Croatia, Portugal, Belgium, France, Germany | 83 | |

| 3 | Wild boars, swine, horses, humans | Croatia, Wallis and Futuna islands | 10 | |

| 4 | Humans, caribou, musk oxen | Canada | 4 | |

| 5 | Human | USA | 1 | |

| B. ovis | Sheep | Spain, Croatia, France, Argentine, USA | 25 | |

| B. canis | Dogs | Romania, Canada, Costa Rica, Madagascar, France, Spain, Brazil, Serbia | 21 | |

| B. neotomae | 1 | |||

| B. ceti | Dolphins, whales, porpoises | Scotland, Norway, Costa Rica, France | 38 | |

| B. pinnipedialis | Seals | Scotland, Greeland Sea | 27 | |

| B. abortus | RB51 | Cattle | Spain, Portugal, USA | 27 |

| B. abortus | S19 | Cattle | Spain, France, USA | 3 |

| B. melitensis | Rev.1 | Sheep, goats, cattle, humans | Spain, France, South Africa, Portugal, Belgium, Israel, USA | 35 |

USA, United States.

FIG. 1.

Differentiation of all Brucella species and S19, RB51, and Rev.1 vaccine strains by Bruce-ladder multiplex PCR. Lane 1 (A), B. abortus; lane 2 (M), B melitensis; lane 3 (O), B. ovis; lane 4 (S), B. suis; lane 5 (S19), B. abortus S19 vaccine strain; lane 6 (RB51), B. abortus RB51 vaccine strain; lane 7 (Rev.1), B. melitensis Rev.1 vaccine strain; lane 8 (C), B. canis; lane 9 (N), B. neotomae; lane 10 (Bp), B. pinnipedialis; lane 11 (Bc), B. ceti.

Although this PCR assay cannot differentiate among biovars from the same species, Bruce-ladder was species specific and all the strains and biovars from the same Brucella species gave the same profile. The practical interest of Bruce-ladder for typing purposes is evident since some of the cumbersome and long-lasting microbiological procedures currently used could be avoided. The specificity of the Bruce-ladder PCR has been tested previously (10), using as targets DNA from 30 strains phylogenetically or serologically related to Brucella. The Bruce-ladder PCR worked equally well irrespective of the cultural conditions, DNA extraction methods, or thermocyclers used. The same results were obtained in seven different laboratories with brucellae obtained from the five continents and from humans and both domestic and wild animals (Table 2), demonstrating without a doubt the reproducibility and robustness of the PCR assay proposed.

One of the most popular PCR assays for the differentiation of Brucella species, designated AMOS PCR (3), was based on the polymorphism arising from species-specific localization of the insertion sequence IS711 in the Brucella chromosome and can differentiate B. abortus (biovars 1, 2, and 4), B. melitensis (biovars 1, 2, and 3), and B. ovis and B. suis (biovar 1). Modifications of this assay have been introduced over the years to improve performance, and additional strain-specific primers were incorporated for identification of the B. abortus S19 and RB51 vaccine strains (2, 4). However, other Brucella species (such as B. canis, B. neotomae, B. pinnipedialis, and B. ceti) and some particular biovars (B. abortus biovars 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9 and B. suis biovars 2, 3, 4, and 5) cannot be detected by AMOS PCR. A major advantage of the Bruce-ladder PCR assay over previously described multiplex PCR tests is that it can identify and differentiate for the first time all of the Brucella species and the vaccine strains in the same test. In contrast to AMOS PCR, Bruce-ladder PCR is also able to detect DNA from B. canis, B. neotomae, Brucella isolates from marine mammals, B. abortus biovars 3, 5, 6, 7, and 9, and B. suis biovars 2, 3, 4, and 5. Other advantages are speed (the PCR can be performed in less than 24 h), minimal sample preparation (it works with whole-cell lysates), and reduced risks (PCR can be carried out with Brucella colonies, limiting the manipulation of live Brucella). In conclusion, Bruce-ladder PCR can be a useful tool for the rapid identification of Brucella strains of animal or human origin, not only in reference centers but also in any basic microbiology laboratory worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Sylvie Malbrecq, Damien Desqueper, Patrick Michel, Martine Thiébaud, and Martine Lapalus for their technical skill and to Geoff Foster, Morten Tryland, and Zeljko Cvetnic for providing some of the Brucella isolates.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 August 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alton, G. G., L. M. Jones, R. D. Angus, and J. M. Verger. 1988. Techniques for the brucellosis laboratory. INRA, Paris, France.

- 2.Bricker, B. J., D. R. Ewalt, S. C. Olsen, and A. E. Jensen. 2003. Evaluation of the Brucella abortus species-specific polymerase chain reaction assay, an improved version of the Brucella AMOS polymerase chain reaction assay for cattle. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 15374-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bricker, B. J., and S. M. Halling. 1994. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 322660-2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bricker, B. J., and S. M. Halling. 1995. Enhancement of the Brucella AMOS PCR assay for differentiation of Brucella abortus vaccine strains S19 and RB51. J. Clin. Microbiol. 331640-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloeckaert, A., M. Grayon, and O. Grepinet. 2000. An IS711 element downstream of the bp26 gene is a specific marker of Brucella spp. isolated from marine mammals. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7835-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cloeckaert, A., M. Grayon, and O. Grepinet. 2002. Identification of Brucella melitensis vaccine strain Rev.1 by PCR-RFLP based on a mutation in the rpsL gene. Vaccine 202546-2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbel, M. J. 1988. International committee on the systematic bacteriology-subcommittee on the taxonomy of Brucella. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38450-452. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster, G., B. S. Osterman, J. Godfroid, I. Jacques, and A. Cloeckaert. 2007. Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 572688-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Yoldi, D., C. M. Marín, and I. López-Goñi. 2005. Restriction site polymorphisms in the genes encoding new members of group 3 outer membrane protein family of Brucella spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 24579-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Yoldi, D., C. M. Marín, M. J. De Miguel, P. M. Muñoz, J. L. Vizmanos, and I. López-Goñi. 2006. Multiplex PCR assay for the identification and differentiation of all Brucella species and the vaccine strains Brucella abortus S19 and RB51 and Brucella melitensis Rev1. Clin. Chem. 52779-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halling, S. M., B. D. Peterson-Burch, B. J. Bricker, R. L. Zuerner, Z. Qing, L. L. Li, V. Kapur, D. P. Alt, and S. S. Olsen. 2005. Completion of the genome sequence of Brucella abortus and comparison to the highly similar genomes of Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis. J. Bacteriol. 1872715-2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulsen, I. T., R. Seshadri, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, T. D. Read, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. M. Brinkac, M. J. Beanan, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, B. Ayodeji, M. Kraul, J. Shetty, J. Malek, S. E. Van Aken, S. Riedmuller, H. Tettelin, S. R. Gill, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, D. L. Hoover, L. E. Lindler, S. M. Halling, S. M. Boyle, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. The Brucella suis genome reveals fundamental similarities between animal and plant pathogens and symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9913148-13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajashekara, G., J. D. Glasner, D. A. Glover, and G. A. Splitter. 2004. Comparative whole-genome hybridization reveals genomic islands in Brucella species. J. Bacteriol. 1865040-5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangari, F. J., J. M. García-Lobo, and J. Agüero. 1994. The Brucella abortus vaccine strain B19 carries a deletion in the erythritol catabolic genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121337-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vemulapalli, R., J. R. McQuiston, G. G. Schurig, N. Sriranganathan, S. M. Halling, and S. M. Boyle. 1999. Identification of an IS711 element interrupting the wboA gene of Brucella abortus vaccine strain RB51 and a PCR assay to distinguish strain RB51 from other Brucella species and strains. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6760-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verger, J. M., F. Grimont, P. A. D. Grimont, and M. Grayon. 1985. Brucella, a monospecific genus as shown by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 35292-295. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vizcaíno, N., J. M. Verger, M. Grayon, M. S. Zygmunt, and A. Cloeckaert. 1997. DNA polymorphism at the omp-31 locus of Brucella spp.: evidence for a large deletion in Brucella abortus, and other species-specific markers. Microbiology 1432913-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.