Abstract

Background

Ambient air pollution may affect the health related quality of life (HRQOL) of people, as assessed by the vitality (VT) and mental health (MH) domains of the SF‐36 health survey (SF‐36).

Methods

In a nationwide survey, 4500 people aged 20 years and older were selected from the entire population of Japan by stratified random sampling in October 2002. A total of 2896 subjects filled out the self administered questionnaire that included the SF‐36 and demographic characteristics. Data were linked from the questionnaires with the data on air pollutants in the cities where the subjects resided. The paper examined the relations between the mean concentration of each air pollutant and the VT or MH score on the SF‐36 using analysis of covariance.

Results

On crude analysis, the respondents who were exposed to a higher mean two month concentration of photochemical oxidants (Ox) showed a significant linear trend toward lower VT score (p = 0.028). This association remained even after adjustment for subjective demographic characteristics and meteorological variables (p = 0.033). There was a common tendency that subjects who were exposed to higher concentrations of Ox had a lower mean VT or MH score; however, there was a significant association only between Ox concentration and VT score.

Conclusion

The score on the VT domain of the SF‐36 was associated with the mean concentration of Ox during the previous two month period. Assessing the health effects of air pollution by measuring the HRQOL, such as by using the SF‐36, may provide a new method of formulating air pollution policies.

Keywords: air pollution, photochemical oxides, mental health, quality of life, vitality

Numerous studies have found associations between ambient air pollution and various health outcomes including mortality, hospitalisation for respiratory or heart disease, lung function, and incidence of respiratory symptoms.1,2 We believe that there are adverse health effects from air pollution other than those reflected in measures of morbidity or mortality. Health related quality of life (HRQOL) refers to how a person feels and functions in everyday life and to the effects of ill health. HRQOL measurements, which were validated scientifically, enable us to measure a population's health status that cannot be measured by morbidity or mortality. As to the relation between air pollution and health, the American Thoracic Society has recognised that a decrease in HRQOL is an adverse health effect of air pollution, and the society has revised guidelines on the distinction between adverse and non‐adverse health effects of air pollution in their revised statement.3 The society also pointed out that evaluation of the adverse health effects of air pollution based on scores of the HRQOL is important for policymakers to establish policies related to both individual health and public health concerns. However, to our knowledge, only one study on the association between the concentration of ambient air pollutants and HRQOL has been reported.4 In that study, the association between air pollutants and HRQOL using the medical outcomes study short form 36‐item health survey (SF‐36) was examined among the Japanese general population in the year of 1995. They found a significant linear trend of a lower score on the vitality (VT) domain of the SF‐36 in subjects who were exposed to higher concentrations of nitrogen oxides (NOx).

However, the ambient concentrations of NOx might be acting as surrogate measures of other agents or to specific pollution sources that are in fact responsible for the observed effects. Moreover, the previous study by Yamazaki et al,4 did not examine the association between photochemical oxidants and HRQOL. It is pointed out that the ambient air quality in Japan has changed in recent years from that in 1995 when the previous study was conducted. Therefore, in this study, we examined the associations between HRQOL, in particular, the vitality and mental health (MH) domains of the SF‐36, and the ambient concentrations of suspended particulate matter (SPM), NOx, and photochemical oxidants (Ox) in 2002.

Methods

Subjects

In this cross sectional study, we used data that had been previously collected for a study that calculated a national standard of scores on the SF‐36 Japanese version in 2002 (hereafter referred to as the nationwide survey). For the nationwide survey, a total of 4500 people 20 years of age and older were selected from the entire population of Japan by stratified random sampling. Data were obtained from the stratified sampling, including the district of residence (Japan was divided into nine districts for this survey) and the population of the city of residence (five classifications according to population: metropolis; city with a population of more than 150 000, between 50 000 and 150 000, or less than 50 000 people; and rural). The nationwide survey was conducted in October 2002. In the nationwide survey, a self administered questionnaire was mailed to the 4500 people, and a visit was made to the residences of the subjects to collect the questionnaires.

Questionnaire and outcome measurements

The self administered questionnaire consisted of the SF‐36 Japanese version and questions on the following items with multiple choice responses: annual household income (five levels: less than 3 million yen, 3–4.9 million yen, 5–6.9 million yen, 7–9.9 million yen, and 10 million yen or more), sex (male or female), age (six levels: less than 30 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, and 70 years or older), and self reported medical conditions including respiratory disease (yes or no). The SF‐36 is a generic instrument based on a conceptual model consisting of physical and mental health constructs and is designed to measure perceived health status and daily functioning. The SF‐36 consists of 36 items, and scores are given for the following eight domains5: physical functioning (PF, 10 items), bodily pain (BP, 2 items), role‐physical functioning (RP, 4 items), role‐emotional functioning (RE, 3 items), social functioning (SF, 2 items), general health perception (GH, 5 items), VT (4 items), and MH (5 items). The SF‐36 was translated into Japanese and the Japanese version was validated for the Japanese general population.6,7,8 We studied the associations between HRQOL, in particular, the scores on the VT and MH domains of the SF‐36, and ambient air pollution. The VT domain is related to the state of fatigue, and the MH domain can detect a depressive state.9 The VT domain of the SF‐36 consists of the following four questions: How much of the time during the past month did you: (a) feel full of pep? (b) have a lot of energy? (c) feel worn out? (d) feel tired? For each question, the subject was asked to choose one of the following responses: all of the time (1 points), most of the time (2 points), some of the time (3 points), a small part of the time (4 points), and none of the time (5 point). Because items (a) and (b) ask about positive feelings, their scoring was reversed. The MH domain of the SF‐36 consists of the following five questions: How much of the time during the past month have you: (e) been a very nervous person? (f) felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up? (g) felt calm and peaceful? (h) felt downhearted and blue? (i) been a happy person? For each question, the subject was asked to choose one of the following responses: all of the time (1 points), most of the time (2 points), some of the time (3 points), a small part of the time (4 points), and none of the time (5 point). Because items (g) and (i) ask about positive feelings, their scoring was reversed. The scores for VT and MH were computed by summing the scores on each question item and then transforming the raw scores to a 0 to 100 point scale, with a lower score showing poorer health status.

Exposure assessments

We linked the data of the SF‐36 from the nationwide survey (subjects, their characteristics, and their HRQOL scores) and the data on air pollutants. The data on air pollutants came from the database of the National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. Air pollutant data were collected by hourly monitoring at about 1700 fixed monitoring stations. In Japan, there are about 700 cities and 2500 towns (villages), and nearly all cities have fixed air pollution monitoring station(s). We used the database to obtain the concentrations of SPM, NOx, and Ox; we obtained the average monthly levels of SPM, NOx, and Ox in September and October of 2002, and the average levels of SPM, NOx, and Ox over the two month period of September to October 2002, because the subjects filled out the questionnaire including the SF‐36 in October 2002, and the SF‐36 asked questions about the person's subjective heath status during the previous one month. That is, the SF‐36 contained items that asked how the person felt during the previous month and if the person filled out the questionnaire in the beginning of October, it was considered that the levels of air pollutants measured in September would be appropriate for examining the association between air pollutants and the responses on the SF‐36. In Japan, SPM is defined under the National Air Quality Standard as particles with an aerodynamic diameter below 10 μm with a 100% cut off point. (The PM10 is defined by the US EPA as particles with an aerodynamic diameter below 10 μm with a 50% cut off point).1 Temperature and relative humidity data for each city were obtained from the Japan Meteorological Agency. The database of the SF‐36 nationwide survey has a field for the name of the city in which the subjects lived. The database of air pollutants also has a field, “name of city”, which contains information on where the air pollutant monitoring stations are located. We linked the data on the subjects and their SF‐36 scores and the data on air pollutants by means of common fields (name of city). We did not assess the association between sulphur dioxide (SO2) and the SF‐36 because concentrations of SO2 in Japan were low and almost always less than10 ppb.

Statistical methods

We converted continuous variables of the concentrations of air pollutants into categorical variables to gain simplicity and avoid certain assumptions about the nature of the data. That is, we divided the data on the concentration of each air pollutant into four equal groups or quartiles. We used analysis of covariance to estimate the adjusted means of the VT and MH scores in the four groups and to examine whether there was a linear trend in the MH or VT scores according to the level of air pollution with a method of contrast. The estimations were adjusted for sex, age, annual household income, size of the city, self reported respiratory disease status, ambient temperature, and ambient relative humidity. Both single and multi‐pollutant models were considered (total of six models: SPM model, NOx model, and Ox model as single pollutant models, SPM + NOx joint model that included SPM and NOx at the same time, SPM + Ox joint model that included SPM and Ox at the same time, and SPM + NOx + Ox joint model that included SPM, NOx, and Ox at the same time). All tests were two tailed, and significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the GLM procedure with a contrast option in the SAS software (release 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The nationwide survey targeted 4500 people, and 2896 returned a completed questionnaire in October 2002 (64% response rate). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 2896 study subjects. The respondents were 47% male with a mean age of 51.2 years (SD = 15.9; range 20 to 81 years). Table 2 summarises the VT and MH scores on the SF‐36 in the 2896 subjects. Table 3 summarises the concentration of air pollutants and temperature and relative humidity of the 300 cities where the subjects resided. With respect to air pollutants in September and October 2002, the two month mean concentrations of SPM, NOx, and Ox were 22.5 μg/m3 (SD = 8.0, range 3.0 to 40.5), 45.0 ppb (SD = 21.3, range 3.5 to 92.0), and 21.0 ppb (SD = 5.7, range 9.5 to 40.0), respectively. Pearson's correlation coefficients between the SPM and NOx levels, between the SPM and Ox levels, and between the NOx and Ox levels were 0.684 (p<0.001), −0.618 (p<0.001), and −0.733 (p<0.001), respectively.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the subjects.

| Number | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2896 | (100) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1352 | (47) |

| Female | 1544 | (53) |

| Age (y) | ||

| 20 to 29 | 347 | (12) |

| 30 to 39 | 438 | (15) |

| 40 to 49 | 487 | (17) |

| 50 to 59 | 605 | (21) |

| 60 to 69 | 603 | (21) |

| 70 to 81 | 416 | (14) |

| Annual household income (million yen)* | ||

| <3 | 547 | (19) |

| 3 to 4.99 | 700 | (24) |

| 5 to 6.99 | 539 | (19) |

| 7 to 9.99 | 422 | (15) |

| 10 or over | 310 | (11) |

| Missing | 384 | (13) |

| Self reported respiratory disease | ||

| No | 2782 | (96) |

| Yes | 114 | (4) |

| Site of residence† | ||

| Major metropolis | 594 | (21) |

| Large city | 887 | (31) |

| Medium sized city | 568 | (20) |

| Small city | 195 | (7) |

| Rural area | 652 | (23) |

*Exchange rate in 31 December 2002 was 125.39 yen for 1 US dollar. †Size of the city of residence was categorised into five classifications according to the population: major metropolises; large cities: city population ⩾150 000; medium sized cities: 50 000 to 149 999; small cities: 30 000 to 49 999; and rural area. The major metropolises are Sapporo, Sendai, Tokyo, Chiba, Kawasaki, Yokohama, Nagoya, Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe, Hiroshima, Kitakyushu, and Fukuoka.

Table 2 Scores on the vitality and mental health domains of the SF‐36 health survey.

| Domains of the SF‐36 | Mean* | (SD) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitality | 62.3 | (20.6) | 0 | 100 |

| Mental health | 71.9 | (19.0) | 0 | 100 |

*The mean scores on the vitality and mental health domains of the SF‐36 among the 2896 subjects are shown.

Table 3 Mean concentrations of air pollutants, temperature, and relative humidity.

| Mean | (SD) | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2002 | |||||||

| SPM (μg/m3) | 25.0 | (10.0) | 4.0* | 17.0 | 24.0 | 32.0 | 48.0† |

| NOx (ppb) | 49.3 | (24.7) | 4.0* | 29.0 | 45.0 | 69.0 | 106.0† |

| Ox (ppb) | 18.4 | (5.9) | 7.0* | 14.0 | 18.0 | 22.0 | 40.0† |

| Temperature (C) | 23.0 | (2.1) | 17.7* | 22.2 | 23.1 | 24.5 | 27.5† |

| Relative humidity (%) | 69.7 | (5.0) | 62.0* | 65.0 | 69.0 | 73.0 | 80.0† |

| October 2002 | |||||||

| SPM (μg/m3) | 20.1 | (6.5) | 2.0* | 15.0 | 20.0 | 25.0 | 34.0† |

| NOx (ppb) | 40.8 | (18.8) | 3.0* | 25.0 | 41.0 | 56.0 | 89.0† |

| Ox (ppb) | 23.5 | (5.8) | 12.0* | 19.0 | 23.0 | 27.0 | 41.0† |

| Temperature (C) | 17.5 | (2.1) | 12.0* | 16.7 | 18.2 | 18.8 | 24.7† |

| Relative humidity (%) | 67.2 | (4.3) | 62.0* | 64.0 | 66.0 | 71.0 | 81.0† |

| September to October 2002 | |||||||

| SPM (μg/m3) | 22.5 | (8.0) | 3.0‡ | 16.5 | 22.5 | 29.0 | 40.5§ |

| NOx (ppb) | 45.0 | (21.3) | 3.5‡ | 27.5 | 43.0 | 63.0 | 92.0§ |

| Ox (ppb) | 21.0 | (5.7) | 9.5‡ | 16.5 | 20.5 | 24.5 | 40.0§ |

| Temperature (C) | 20.2 | (2.0) | 14.9‡ | 19.5 | 21.0 | 21.6 | 26.1§ |

| Relative humidity (%) | 68.4 | (4.3) | 63.0‡ | 65.0 | 66.5 | 71.0 | 80.5§ |

Mean, the lowest, the mediate, and the highest concentrations of air pollutants, temperature, and relative humidity at the 300 locations where the subjects resided. *The mean monthly concentration in the city with the lowest mean monthly concentration. †The mean monthly concentration in the city with the highest mean monthly concentration. ‡The two month mean concentration in the city with the lowest two month mean concentration. §The two month mean concentration in the city with the highest two month mean concentration. SPM, suspended particulate matter; NOx, nitrogen oxides; Ox, photochemical oxidants.

Table 4 shows the non‐adjusted associations between the concentration of air pollutants and the VT and MH scores on the SF‐36. There were inverse linear trends between the mean one month or mean two month concentration of Ox and the VT score (test for linear trend for mean one month (September) exposure: p = 0.043; for mean two month exposure: p = 0.027) (table 4). There were also inverse linear trends between the mean one month or mean two month concentration of Ox and the MH score (test for linear trend for mean one month (September) exposure: p = 0.046; for mean two month exposure: p = 0.018) (table 4). On the other hand, there were significant positive linear trends between the mean one month concentration of SPM and the VT score (test for linear trend for mean one month (September) exposure, p = 0.016; for mean one month (October) exposure, p = 0.021). There was also a linear trend between two month concentration of SPM and VT (test for liner trend: p = 0.027). After adjustment for sex, age, annual household income, size of the city, self reported respiratory disease status, temperature, and relative humidity, we only found an association between the one month Ox level and the VT score on the SF‐36 (test for linear trend for mean one month (September) exposure, p = 0.047). With respect to the mean two month concentration of air pollutants, the adjusted association between the Ox level and the VT score also remained significant (table 5) (test for linear trend: p = 0.033).

Table 4 Mean scores on the vitality and the mental health domains on the SF‐36 based on various exposure categories (results of crude analysis).

| Quartile* of data according to the concentration of air pollutants | Month(s) and air pollutants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 2002 | October 2002 | September and October 2002 | |||||||

| SPM | NOx | Ox | SPM | NOx | Ox | SPM | NOx | Ox | |

| Vitality | |||||||||

| 1st Q | 62.2 | 62.0 | 63.7 | 61.4 | 61.5 | 63.4 | 62.2 | 61.7 | 63.7 |

| 2nd Q | 61.1 | 61.1 | 62.6 | 61.1 | 62.7 | 62.7 | 60.8 | 61.6 | 62.8 |

| 3rd Q | 62.0 | 63.1 | 62.3 | 64.0 | 61.8 | 62.2 | 62.6 | 63.2 | 62.4 |

| 4th Q | 64.7 | 63.5 | 61.4 | 63.1 | 63.8 | 61.9 | 64.2 | 63.2 | 61.2 |

| p (test for linear trend) | 0.016† | 0.063 | 0.043‡ | 0.021† | 0.079 | 0.166 | 0.027† | 0.080 | 0.028‡ |

| Mental health | |||||||||

| 1st Q | 72.1 | 71.4 | 73.3 | 71.4 | 71.2 | 72.8 | 72.1 | 71.3 | 73.2 |

| 2nd Q | 71.6 | 71.2 | 71.6 | 72.1 | 71.5 | 72.5 | 71.1 | 71.0 | 72.5 |

| 3rd Q | 71.5 | 72.4 | 72.0 | 72.9 | 72.5 | 71.9 | 72.5 | 73.2 | 71.7 |

| 4th Q | 73.3 | 72.9 | 70.9 | 71.9 | 72.7 | 70.9 | 72.5 | 72.3 | 70.8 |

| p (test for linear trend) | 0.266 | 0.078 | 0.046‡ | 0.506 | 0.083 | 0.060 | 0.450 | 0.117 | 0.018‡ |

*The 1st quartile included the minimum concentration of the air pollutant and the 4th quartile included the maximum concentration. †p Value less than 0.05 with positive association between the concentration of air pollutant and domain score on the SF‐36, in which a higher score shows better health status. ‡p Value less than 0.05 with negative association between the concentration of air pollutant and domain score on the SF‐36, in which a higher score shows better health status. SPM, suspended particulate matter; NOx, nitrogen oxides; Ox, photochemical oxidants.

Table 5 The p values of test for linear trend for the association between the mean concentration of air pollutant(s) and the vitality or the mental health domain score on the SF‐36 (results of adjusted analysis).

| Air pollutants included in the model* | September 2002 | October 2002 | September and October 2002 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPM | NOx | Ox | SPM | NOx | Ox | SPM | NOx | Ox | |

| Vitality | |||||||||

| SPM | 0.061 | – | – | 0.062 | – | – | 0.176 | – | – |

| NOx | – | 0.087 | – | – | 0.063 | – | – | 0.085 | – |

| Ox | – | – | 0.047† | – | – | 0.303 | – | – | 0.033† |

| SPM + NOx | 0.364 | 0.873 | – | 0.360 | 0.215 | – | 0.789 | 0.415 | – |

| SPM + Ox | 0.660 | – | 0.216 | 0.192 | – | 0.663 | 0.896 | – | 0.162 |

| SPM + NOx + Ox | 0.704 | 0.765 | 0.174 | 0.377 | 0.334 | 0.828 | 0.898 | 0.922 | 0.228 |

| Mental health | |||||||||

| SPM | 0.712 | – | – | 0.540 | – | – | 0.934 | – | – |

| NOx | – | 0.393 | – | – | 0.263 | – | – | 0.411 | – |

| Ox | – | – | 0.165 | – | – | 0.315 | – | – | 0.108 |

| SPM + NOx | 0.481 | 0.249 | – | 0.990 | 0.228 | – | 0.462 | 0.295 | – |

| SPM + Ox | 0.363 | – | 0.072 | 0.950 | – | 0.298 | 0.283 | – | 0.063 |

| SPM + NOx + Ox | 0.268 | 0.775 | 0.098 | 0.865 | 0.912 | 0.367 | 0.357 | 0.740 | 0.072 |

*Variables included in the model in addition to the indicated air pollutant(s) are age, sex, household income, self reported respiratory disease status, size of the city of residence (by population), temperature, and relative humidity. †p Value less than 0.05 with negative association between the concentration of air pollutant and the domain score on the SF‐36, in which a higher score show better health status. SPM, suspended particulate matter; NOx, nitrogen oxides; Ox, photochemical oxidants.

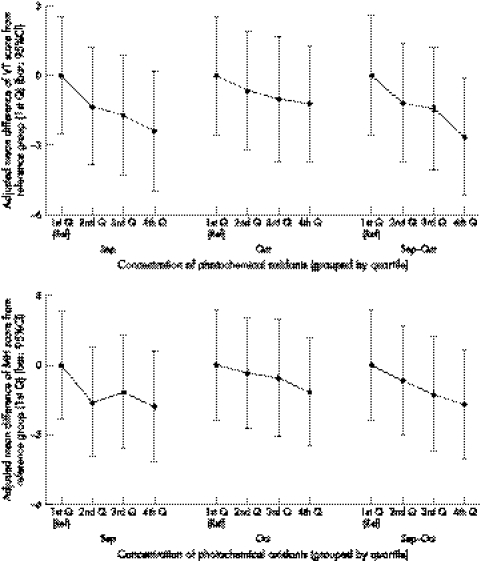

Figure 1 shows the associations between the concentration of Ox and the VT or MH score after adjustment for sex, age, annual household income, size of the city, self reported respiratory disease status, temperature, and relative humidity, in each of September and October and in the two month period from September to October. The three graphs show that there was a common tendency that subjects who were exposed to higher concentrations of Ox had a lower mean VT or MH score; however, there were significant associations only between the mean two month Ox concentration and the VT score and between the mean monthly (September) Ox concentration and VT score.

Figure 1 Associations between the score on the vitality (VT) or mental health (MH) domain of the SF‐36 health survey and the concentration of photochemical oxidants (Ox) after adjustment for age, sex, household income, self reported respiratory disease status, size of the city of residence (by population), temperature, and relative humidity (single pollutant model). The association between VT/MH and Ox level was estimated separately for each month and for the two month period. In each analysis, the reference group was the first quartile, which was composed of subjects who were exposed to the lowest concentration of Ox.

Discussion

We found significant linear trends in which subjects who were exposed to higher concentrations of Ox had a lower mean VT score on the SF‐36, and those who were exposed to higher concentrations of SPM had a higher mean VT score on crude analysis. Only the association between Ox concentration and VT score remained after adjustment for demographic characteristics and meteorological variables. A higher Ox concentration may have a more deleterious effect on human health than other air pollutants. However, we cannot deny completely that the significant associations resulted from chance. We found a common tendency with respect to this association among various exposure conditions; however, we only saw significant associations between the mean monthly (September) or two month Ox concentration and VT score (fig 1). The difference in the mean VT score between the highest Ox concentration group (the 4th quartile) and the lowest Ox concentration group (the 1st quartile) was about two points, while the difference in the mean MH score between the two groups was about one point (fig 1). However, because many people are exposed to air pollutants, a small difference in the HRQOL score is very important evidence in formulating public health policies. For example, if the mean MH score on the SF‐36 decreased by 10 points, the prevalence of depression disorder would be expected to increase by 4% to 8% among the general population of Japan.8 Therefore, if 30 million people (one quarter of the entire population of Japan) were exposed to higher Ox concentration and their mean MH score decreased by one point, about 120 000 people may newly develop depression.

We examined the associations using a multi‐pollutants model, which was similar to the single pollutant models. However, as the two month concentrations of various air pollutants were moderately or highly correlated with each other, the results of a multi‐pollutants model would be affected by multicollinearity among the concentrations of air pollutants. In the multi‐pollutants model, we could not found any significant associations between the concentration of air pollutants and the VT or MH score.

The previous study4 conducted using data collected in 1995 found a significant association between the NOx level and VT. However, in this study, there was no association between these two parameters in data collected in 2002. One possible explanation is that the ambient air quality in Japan has changed in recent years from that in 1995. The ambient concentrations of SPM and NOx in 2002 were low compared with the respective concentrations in 1995. However, the ambient concentration of Ox was higher in 2002 than in 1995 (table 6). Changes in air quality may affect the associations between air pollutants and HRQOL.

Table 6 Comparison of the concentrations of air pollutants in 1995 and 2002.

| Central area of Tokyo (Minato‐ku) | Suburb of Tokyo (Hachioji) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2002 | 1995 | 2002 | |

| Monthly concentration of air pollutants in October | ||||

| SPM (μg/m3) | 40 | 37 | 51 | 32 |

| NOx (ppb) | 56 | 46 | 53 | 39 |

| Ox (ppb) | 16 | 23 | 25 | 30 |

| Annual concentration of air pollutants | ||||

| SPM (μg/m3) | 44 | 34 | 46 | 30 |

| NOx (ppb) | 57 | 49 | 54 | 40 |

| Ox (ppb) | 20 | 25 | 29 | 30 |

SPM, suspended particulate matter; NOx, nitrogen oxides; Ox, photochemical oxidants.

The VT domain of the SF‐36 is related to the state of fatigue and feeling worn out on one end, and energy and pep on the other end. The MH domain can detect a depressive state.9 Why would a person who is exposed to a high level of Ox feel fatigue or feel downhearted and blue? A previous study showed that the mental component summary (MCS), which includes the VT and MH scores, of the SF‐36 was significantly worse in those with wheeze in the preceding 12 months than in those without wheeze.10 Asthma patients' concerns regarding their asthma tend to include the frequency of symptoms, limitation in activities, and avoidance of irritants.11 Exposure to a high level of Ox induces various adverse health effects including increased incidence of respiratory symptoms.1,2 We believe that there are adverse health effects from Ox besides those that are reflected in the clinical diagnosis of asthma or subjective respiratory symptoms.

What this paper adds

Low vitality on the SF‐36 health survey was associated with exposure to high concentrations of photochemical oxidants.

The association was independent of the characteristics of the subjects and meteorological factors.

On the other hand, “noise” in an urban area could also influence the quality of sleep and HRQOL of people, while air pollution and noise problems have some close relation. Some have suggested that traffic density might be correlated with the concentration of NOx, mainly originating from exhaust from automobile engines. A simple comparison between air pollution measurements and HRQOL would be confounded by noise or the characteristics of the subjects' residences. To minimise the confounding effect, we examined the association after adjustment for the site of residence in this study. Similarly, the ambient concentrations of air pollutants might be acting as surrogate measures of exposure to other agents or to specific pollution sources that are in fact responsible for the observed effects. For example, there is an unknown mechanism whereby exposure to ambient air pollutants might diminish VT or MH. Some researchers suggested that traffic density and traffic related noise or annoyances diminished general mental health and that traffic density might be correlated with the concentration of ambient air pollutants, which mainly originate from the exhaust of automobile engines.12,13 However, we could not confirm this explanation in this study.

The response rate of 64% in the nationwide survey is rather low. We calculated the response rate across the site of residence, and we found differences in the response rate among them. The response rates of subjects living in major metropolises, large cities, medium sized cities, small cities, and rural area were 59%, 64%, 64%, 72%, and 69%, respectively. The concentrations of air pollutants in major cities are higher than those in other areas; therefore, the proportion of subjects who were exposed to a high level of pollutants among the 2896 study subjects in this study was lower than that in the non‐biased general population. Moreover, it is considered that people with a mental disorder tend not to reply to a questionnaire such as the SF‐36. These speculations suggest that the proportion of subjects who were exposed to a high concentration of Ox and the proportion of subjects who had low MH and VT scores in our study were smaller than the respective proportions in the general population, and it would take the associations between air pollution and MH or VT score toward null.

Another limitation of this study was that we could not measure the effect of indoor space heating on the NOx concentration. However, in Japan, indoor space heating is usually used in the winter, especially December to February. This study was performed in October; therefore, we believe that the effect of indoor space heating on the association between the concentration of NOx and HRQOL was small.

In this study, the health outcome was measured at only a single point in time. A study that repeatedly measured VT and MH scores on the SF‐36 over time would be able to compare changes in pollution levels with changes in health status for a given population, which would be a more powerful analysis. Further studies are needed to confirm the results of this study.

Policy implications

This study suggests that the vitality domain of the SF‐36 health survey (SF‐36) is a possible effective tool for evaluating the many impacts of photochemical oxidants on the health of people.

Assessing the health effects of air pollution by measuring health related quality of life (HRQOL) may provide a new method of formulating air pollution policies.

We propose that the SF‐36 is a valid tool for measuring the HRQOL with which to assess air quality policies, and these findings may play a part in promoting effective policies to improve the quality of life and improve societal health.

Further studies are needed to explain the causal relation between various air pollutants and HRQOL.

In conclusion, the score on the VT domain of the SF‐36 of people assessed in October was significantly associated with the mean concentration of Ox during the previous two month period from September through October. This study suggests that the VT domain of the SF‐36 is a possible effective tool for evaluating the many impacts of Ox on the health of individuals. Assessing the health effects of air pollution by measuring the HRQOL would provide a new method of formulating air pollution policies. We propose that the SF‐36 is a valid tool for measuring the HRQOL with which to assess air quality policies, and our findings may play a part in promoting effective policies for improving the quality of life and improving societal health. Further studies are needed to explain the causal relation between various air pollutants and the HRQOL.

Abbreviations

VT - vitality

MH - mental health

Ox - photochemical oxidants

SF‐36 - short form‐36 health survey

HRQOL - health related quality of life

NOx - nitrogen oxides

SPM - suspended particulate matter

Footnotes

Funding: this study was granted by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology, Japan.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.US Environmental Protection Agency Air quality criteria for particulate matter. Washington: US Environmental Protection Agency, 2004

- 2.World Health Organisation Air quality guidelines for Europe. Geneva: WHO, 2000 [PubMed]

- 3.American Thoracic Society What constitutes an adverse health effect of air pollution? Official statement of the American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000161665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamazaki S, Nitta H, Murakami Y.et al Association between ambient air pollution and health‐related quality of life in Japan: ecological study. Int J Environ Health Res 200515383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware J E, Snow K K, Kosinski M.et alSF‐36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: New England Medical Center, 1993

- 6.Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J.et al Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF‐36 health survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol 1998511037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuhara S, Ware J E, Kosinski M.et al Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF‐36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998511045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuhara S, Suzukamo Y.Manual of SF‐36v2 Japanese version. (in Japanese). Kyoto, Institute for Health Outcomes and Process Evaluation Research 2004

- 9.Berwick D M, Murphy J M, Goldman P A.et al Performance of a five‐item mental health screening test. Med Care 199129169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matheson M, Raven J, Woods R K.et al Wheeze not current asthma affects quality of life in young adults with asthma. Thorax 200257165–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmier J K, Chan K S, Leidy N K. The impact of asthma on health‐related quality of life. J Asthma 199835585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kageyama T, Kabuto M, Nitta H.et al A population study on risk factors for insomnia among adult Japanese women: a possible effect of road traffic volume. Sleep 199720963–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stansfeld S A. Noise, noise sensitivity and psychiatric disorder: epidemiological and psychophysiological studies. Psychol Med 199222(suppl)1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]