Abstract

The MurNAc etherase MurQ of Escherichia coli is essential for the catabolism of the bacterial cell wall sugar N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) obtained either from the environment or from the endogenous cell wall (i.e., recycling). High-level expression of murQ is required for growth on MurNAc as the sole source of carbon and energy, whereas constitutive low-level expression of murQ is sufficient for the recycling of peptidoglycan fragments continuously released from the cell wall during growth of the bacteria. Here we characterize for the first time the expression of murQ and its regulation by MurR, a member of the poorly characterized RpiR/AlsR family of transcriptional regulators. Deleting murR abolished the extensive lag phase observed for E. coli grown on MurNAc and enhanced murQ transcription some 20-fold. MurR forms a stable multimer (most likely a tetramer) and binds to two adjacent inverted repeats within an operator region. In this way MurR represses transcription from the murQ promoter and also interferes with its own transcription. MurNAc-6-phosphate, the substrate of MurQ, was identified as a specific inducer that weakens binding of MurR to the operator. Moreover, murQ transcription depends on the activation by cyclic AMP (cAMP)-catabolite activator protein (CAP) bound to a class I site upstream of the murQ promoter. murR and murQ are divergently orientated and expressed from nonoverlapping face-to-face (convergent) promoters, yielding transcripts that are complementary at their 5′ ends. As a consequence of this unusual promoter arrangement, cAMP-CAP also affects murR transcription, presumably by acting as a roadblock for RNA polymerase.

N-Acetylmuramic acid {MurNAc; 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-3-O-[(R)-1-carboxyethyl]-d-glucopyranose} is an amino sugar, naturally occurring in the cell wall of almost all eubacteria. We have shown recently that utilization of MurNAc by Escherichia coli depends on the MurNAc-specific membrane component (EIIBCMurNAc or MurP) of the phosphotransferase system (PTS) along with the general soluble PTS components EI and HPr, as well as the glucose-specific enzyme IIA (EIIAGlc) (11). The PTS translocates the amino sugar across the cell membrane while phosphorylating it, receiving the phosphate ultimately from phosphoenolpyruvate and yielding intracellular MurNAc-6-phosphate (MurNAc-6-P). Further metabolism within the cytoplasm requires the MurNAc etherase MurQ, a unique lyase/hydrolase which catalyzes a β-elimination reaction to cleave the lactyl ether bond of MurNAc-6-P, yielding N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcNAc-6-P) and d-lactate (19). Subsequently, the proteins of the GlcNAc-6-P or nag pathway yield fructose-6-phosphate, which enters glycolysis (31).

MurNAc-6-P is also generated in a process called “cell wall recycling.” During elongation and division of E. coli, when new cell wall material is synthesized and integrated into the existing wall, the peptidoglycan (murein) of the cell wall is continuously degraded and the turnover products are imported into the cytoplasm, where the muropeptide l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-meso-diaminopimelic acid (Dap) was shown by Goodell to be reutilized (i.e., recycled) (15). During cell wall turnover the 1,6-anhydro form of MurNAc (anhydroMurNAc) is generated by a special class of muramidases, the lytic transglycosylases (16). These cleave the glycosidic MurNAc-GlcNAc bond in peptidoglycan by catalyzing an intramolecular transglycosylation reaction, releasing GlcNAc-anhydroMurNAc peptides from the cell wall. These in turn are taken up from the periplasm by the secondary transporter AmpG (18) and are further processed in the cytoplasm, finally yielding anhydroMurNAc (28, 39). AnhydroMurNAc can also be taken up by MurP, but in contrast to MurNAc this sugar is not phosphorylated by the PTS (40). Instead, the further degradation of anhydroMurNAc depends on phosphorylation by the cytoplasmic anhydroMurNAc kinase AnmK, which yields MurNAc-6-P (41). Hence, the cell wall recycling and MurNAc utilization pathways merge at the level of MurNAc-6-P and the MurNAc etherase is required for both processes, as was shown recently (40).

Low-level constitutive expression of the etherase is sufficient for the degradation of cell wall fragments that are released continuously during growth (15). In contrast, high-level expression of murQP is essential for growth on MurNAc as the sole source of carbon and energy (11, 19). In consequence, murQP needs to be differentially regulated in response to the physiological requirement of the cell (40). In conjunction with operon-specific regulators, a large number of genes, including many involved in the PTS-dependent sugar metabolism, are subject to a regulatory effect called “catabolite repression” (13). In this scheme, the phosphorylation state of EIIAGlc determines the activity of the adenylate cyclase to produce cyclic AMP (cAMP), which in turn binds to catabolite activator protein (CAP; also known as cAMP receptor protein) (8). Binding of cAMP-CAP to the promoter region of catabolite-sensitive genes is the prerequisite for their transcription, which means that in the presence of a preferred sugar, e.g., glucose in E. coli, the utilization of nonpreferred nutrients is silenced until the cell has completely consumed the preferred sugar.

To further understand the regulation of the E. coli MurNAc etherase, we addressed its differential transcriptional regulation by specific and global regulators.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, sugars, and sugar phosphates.

All chemicals, sugars, and sugar phosphates were from Sigma unless otherwise stated. MurNAc and muramic acid (MurN) were from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). AnhydroMurNAc was kindly provided by Niels Kubasch (FB Chemie, University of Konstanz). MurNAc-6-phosphate was prepared from TJ2 cells grown on minimal medium A (MMA) supplemented with glycerol, as described previously (19).

Strains, plasmids, promoter fragments, and growth conditions.

E. coli strains, plasmids, and promoter fragments used in the present study are listed in Table 1; the primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Strains were cultivated in shaking flasks at 37°C in MMA (25) containing one or a combination of the following carbon sources: 0.1 or 0.2% MurNAc (3.41 or 6.82 mM, respectively), 0.2% glucose (11.11 mM), 0.4% glycerol (4.3 mM), or 1% Casamino Acids (CAA; Becton Dickinson AG). When needed, ampicillin (100 or 25 μg ml−1), kanamycin (50 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1), and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG, 0.05 mM) were added as supplements to the growth medium. DNA preparations, restriction enzyme digestions, ligations, and transformations were performed according to standard techniques. Genes and DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA from E. coli K-12 strain MG1655 (4) and Pwo DNA polymerase (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany). murR (formerly yfeT) of E. coli was cloned into vector pCS19 (37), generating plasmid pTB6. This construct fuses murR to a C-terminal His tag and puts it under the control of the T5 promoter and the lac repressor, which is constitutively transcribed from the plasmid. For the construction of transcriptional phoA and lacZ fusions, the murR-murQ intergenic region that carries the divergent promoters for murQ and murR was cloned (using BamHI and BglII sites) in both orientations into the “divergent promoter-cloning vector” pTAC3575 (1), resulting in two plasmids with different transcriptional fusions: pPRO2 (murQ-lacZ, murR-phoA) and pPRO7 (murR-lacZ, murQ-phoA). For construction of chromosomal transcription fusions, pPRO2 and pPRO7 were integrated into the lambda prophage attachment site of the E. coli MC4100 chromosome using the lambda InCh integration system as described in reference 5, yielding single-copy chromosomal fusions. murR was deleted in E. coli DY330 by homologous replacement with a kanamycin resistance cassette (Kmr) with modifications (11) of published protocols (12, 44). In brief, Kmr was amplified from plasmid pKD13 (12), integrated into DY330, and then transferred by phage P1 transduction (25) into strain MC4100 (10), yielding the deletion strain TJ103.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and promoter fragments used in the present work

| Name | Relevant genotype and features | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| MG1655 | Sequenced E. coli K-12 | 4 |

| MC4100 | E.coli K-12 F− Δ(argF-lac)U169 flbB5301 araD139 deoC1 relA1 rbsR rpsL150 ptsF25 | 10 |

| DY330 | W3110 F− Δ(argF-lac)U169 gal-490 (λ cI857 Δcro/broA), heat-inducible λRED recombination system | 44 |

| BL21 | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm | 38 |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | 38 |

| TJ2 | MC4100 murQ::Kmr | 19 |

| TJ103 | MC4100 murR::Kmr | This work |

| TJ105 | MC4100 murR::KmrmurQ-lacZ murR-phoA | This work |

| TJ106 | MC4100 murR::KmrmurR-lacZ murQ-phoA | This work |

| TJ107 | MC4100 murQ-lacZ murR-phoA | This work |

| TJ108 | MC4100 murR-lacZ murQ-phoA | This work |

| TJ114 | MC4100 crp::KmrmurQ-lacZ | This work |

| TJ117 | MC4100 murQ::KmrmurQ-lacZ | This work |

| TJ119 | MC4100 murP::KmrmurQ-lacZ | This work |

| TJ123 | MC4100 anmK::CmrmurQ-lacZ | This work |

| TJ126 | MC4100 murP::KmranmK::CmrmurQ-lacZ | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCS19 | Expression vector based on pQE31 (Qiagen) Ampr, carrying the constitutively expressed lac repressor lacIq | 37 |

| pET15b-crp | crp with N-terminal His6 tag (NdeI/BamHI) | S. Seitz (unpublished data) |

| pPRO2 | murQ-lacZ murR-phoA; derivative of pTAC3575 | This work |

| pPRO7 | murR-lacZ murQ-phoA; derivative of pTAC3575 | This work |

| pTAC3575 | Divergent promoter cloning vector, promoterless lacZ; phoA Ampr; transcriptional fusions | 1 |

| pTB6 | NcoI and BglII C-terminal His6 fusion protein, derivative of pCS19 | This work |

| pKD13 | Ampr Kanr, PCR template for homologous gene displacement | 12 |

| Promoter fragments | ||

| reg I | Amplified with ProF/ProR; carrying 5′ murR (1-108), 5′ murQ (1-93), and the binding sites for CAP and MurR | This work |

| reg II | Amplified with ProF/ProCAP-R; carrying the consensus CAP site | This work |

| reg III | Amplified with ProCAP-F/ProRR; carrying the MurR binding site | This work |

| reg IV | Amplified with ProRF/ProR; carrying no binding sites for CAP or MurR | This work |

Detection of the murQ and murR transcription start sites.

The transcription start sites were identified with the 5′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was prepared from logarithmically growing cultures with the RNA minipreparation kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). TJ103 grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth was used to prepare RNA for identification of the murQP operon transcriptional start site, and MC4100 grown on MMA with 0.4% glycerol and 0.1% MurNAc was used to prepare RNA for identification of the murR operon start site. The primers used for reverse transcription and amplification of cDNA by PCR are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The resulting PCR products were sequenced by GATC (Konstanz, Germany). The transcription start sites were determined in three independent experiments with different RNA preparations obtained from cultures grown under different conditions.

Purification of MurR and CAP.

The regulator MurR was expressed in E. coli BL21 carrying pTB6. The strain was grown in LB with ampicillin (200 μg ml−1) at 37°C to an optical density at 578 nm of 0.6, and then IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.05 mM and cultivation was continued for 4 h with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), and disrupted using a French cell disrupter. Debris and unbroken cells were removed by ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 60 min). The His-tagged protein was found within the supernatant and was purified on a 5-ml HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein was eluted with a linear gradient from 20 to 500 mM imidazole. The peak fractions (at 160 mM imidazole) were pooled and stored at 4°C.

Purification of CAP was performed using BL21(DE3) cells that contained the plasmid pET15b-crp (Sabine Seitz, unpublished data). Induction and purification were carried out essentially as described for MurR, using a buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0. The peak fractions (at 175 mM imidazole) were pooled and stored at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to a published method (6).

Size determination of MurR.

Oligomeric forms of MurR were separated by gel filtration chromatography. Protein purified by nickel chelating chromatography (0.25 ml; 1 mg ml−1) was applied to a Superdex 200 HR1030 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.5, and eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. The fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against the His tag as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen; QIAexpress). The molecular weight of MurR under the conditions of gel filtration was determined in three independent experiments using a BioSep-SEC-S3000 high-pressure liquid chromatography column (600 × 7.8 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex) and two molecular mass standard mixtures for size calibration (I: RNase A, 13.7 kDa; ovalbumin, 43 kDa; aldolase, 158 kDa; II: chymotrypsinogen, 25 kDa; albumin, 67 kDa; catalase, 232 kDa; Amersham Biosciences). The hydrodynamic radius of MurR was measured, and the molecular mass was calculated by dynamic light scattering using a DynaPro99E instrument from Protein Solutions (Lakewood, NJ). The instrument was calibrated with buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.5). Once a stable baseline of 1.0 was established, 12 μl of concentrated MurR (gel filtration pooled fractions; 3 mg ml−1 protein in calibration buffer) was injected and data were recorded at 20°C.

EMSA.

DNA fragments containing various parts of the murR-murQ intergenic region were amplified by PCR using the plasmid pPRO2 as template (the DNA fragments are listed in Table 3; the primers are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material). The fragments were gel purified (gel extraction kit; Qiagen) and 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (10 μCi; Hartmann Analytic GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) and 10 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase (Fermentas, Ontario, Canada). Excessive [γ-32P]ATP was removed with mini-Quick-Spin-Oligo columns (Roche Diagnostics). Binding of MurR or cAMP-CAP to the radioactively labeled DNA fragments was performed in HEPES-potassium glutamate buffer (25 mM HEPES, 150 mM potassium glutamate, pH 8) containing 0.5 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin as described in reference 30. For the electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) performed with CAP, the samples and the electrophoresis buffer, in addition, contained cAMP (200 μM). Proteins were diluted in the same buffer and mixed with [γ-32P]ATP-labeled DNA (−2.7 to 5.5 nCi, 0.5 to 1 μg) and 0.5 μg of unspecific competitor polynucleotides [poly(dI-dC); Roche Diagnostics] within a final volume of 10 μl. The samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then mixed with 5 μl of the same buffer supplemented with 40% glycerol and bromophenol blue. Free DNA and MurR-DNA complexes were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris base, 89 mM sodium borate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3). The EMSA products were visualized on a phosphorimager (FLA-7000; Fuji-Film).

TABLE 3.

Influence of catabolite repression on the expression of chromosomal murQ-lacZ transcriptional fusions

| Carbon source | Sp act (mU mg−1)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TJ107 (murR+ murQ-lacZ)

|

TJ105 (ΔmurR murQ-lacZ)

|

|||

| First exponential phase | Stationary phase/second exponential phase | First exponential phase | Stationary phase/second exponential phase | |

| Glucose | ND | ND | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 8.0 ± 3.0 |

| Glucose/MurNAc | ND | 11.0 ± 4.0 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 15.8 ± 0.9 |

| CAA | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 20.3 ± 7.8 | 13.7 ± 2.6 |

| CAA/MurNAc | 23.4 ± 4.5 | 7.0 ± 4.6 | 23.3 ± 7.2 | 9.0 ± 0.8 |

Bacteria were grown overnight in MMA supplemented with the carbon source indicated. Growth on glucose (0.2%) represents catabolite repression conditions, whereas growth on CAA (1%) represents non-catabolite repression conditions. Note that in both cases diauxic growth occurred when MurNAc (0.1%) was added; however, glucose is metabolized prior to MurNAc, whereas CAA are utilized after MurNAc has been consumed. β-Galactosidase activities (specific enzymatic activities) are the means of two independent experiments with the standard deviations, which were measured in the exponential growth phase/first exponential phase (8.5 h) and in the stationary phase/second exponential phase (23 h). The parental strain MC4100 has no β-galactosidase. ND, not detectable.

DNase I protection assay.

A radioactively labeled DNA fragment containing the entire MurR operator region was generated by PCR using the primers ProF and ProR (listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material). A primer combination was used that contains one unlabeled primer and a second primer 5′ labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (10 units) and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. As PCR template unlabeled PCR product of the operator region was used. The resulting PCR product was purified with the PCR purification kit (Qiagen). About 11 nCi of the labeled DNA was incubated with various amounts of MurR in a total volume of 25 μl (conditions were as described for the EMSA). The DNase I digest was carried out using 0.005 units of DNase I (GE Healthcare) at 37°C for 1 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl stop solution containing 20 mM EDTA, 0.4 M sodium acetate, pH 5.0, and 10 μg ml−1 herring sperm DNA. The protein was removed with phenol-chloroform followed by a chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction. The DNA was precipitated with 2.5 volumes of 96% ethanol with 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.0) at −20°C for 2 h. After centrifugation the DNA pellet was washed once with 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in sequencing stop solution (MBI Fermentas). The samples were heated to 95°C for 3 min and applied directly onto a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel containing 7 M urea. A sequencing reaction with the corresponding primer was run in parallel.

Enzyme assays.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined according to the method of Miller (25) with a few alterations. Hydrolysis of orthonitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside (ONPGal) in CHCl3-sodium dodecyl sulfate-permeabilized cells was performed at 28°C. After the reaction was stopped with sodium carbonate (1 M), the suspension was clarified by centrifugation prior to measurement of the optical density at 405 nm. To calculate the specific activity, an extinction coefficient for orthonitrophenol of 4,860 mol−1 cm−1 was used. Specific activity (U mg protein−1) was given in μmol ONPGal hydrolyzed per min per mg protein at 28°C. All cultures were assayed in duplicate, and reported values are averaged from two or three independent experiments.

The depletion of MurNAc from the medium was detected with the Morgan-Elson assay following a protocol described earlier (19).

RESULTS

Identification of the repressor of the MurNAc etherase operon.

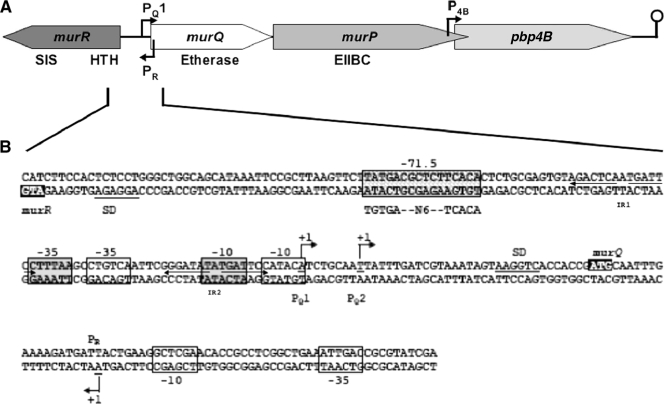

Figure 1A depicts the chromosomal organization of the MurNAc catabolic operon of E. coli, murQP, encoding the MurNAc etherase (19) and the MurNAc-specific EIIBC of the PTS (11). The gene pbp4B is located downstream of murP, and a putative promoter was identified within murP; a deletion of this gene had no effect on growth on MurNAc (T. Jaeger and C. Mayer, unpublished data), and its physiological role is so far unclear, although its product has been reported to weakly bind penicillin and on this account was named penicillin-binding protein 4B (42). Adjacent to murQ on the chromosome and orientated in the opposite direction lies an open reading frame designated murR (formerly yfeT), displaying high sequence identity with transcriptional regulators of the RpiR/AlsR family, and like these it carries an N-terminal DNA binding helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif and a C-terminal sugar phosphate binding (SIS) domain. The three currently known members of the RpiR/AlsR family all control sugar phosphate metabolic pathways. RpiR (AlsR) controls the utilization of d-allose in E. coli by repressing the alsRBACEK and alsI (rpiB) operons (22, 32, 36). After uptake by an ABC transporter (AlsABC), d-allose is converted by a kinase (AlsK) to allose-6-P, which functions as an inducer and is further metabolized by a 3-epimerase (AlsE). HexR is the repressor of the genes of the hex regulon (controlling the expression of the genes of the 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate pathway) (33). Moreover, GlvR (YfiA) is the activator of the maltose PTS of Bacillus subtilis (43) and controls the expression of the glvARC operon. After maltose is taken up and concomitantly phosphorylated by GlvC/MalP (34), maltose 6-phosphate, the coactivator of the maltose PTS, is cleaved by the 6-phospho-α-glucosidase GlvA.

FIG. 1.

Organization of the MurNAc etherase chromosomal region of E. coli and nucleotide sequence of the murR-murQ intergenic (promoter/operator) region. (A) The genes of the MurNAc etherase operon (drawn to scale) and their encoded proteins, respectively, are the following: murQ, MurNAc etherase; murP, MurNAc-specific EIIBC of the PTS; pbp4B, low-affinity penicillin binding protein 4B. Upstream of murQ and divergently transcribed is murR, which encodes the transcriptional regulator of the MurNAc etherase operon. Horizontal arrows indicate the convergent transcription start sites for murQ (PQ1) and murR (PR), as well as the predicted start site for dacB transcription (P4B). The predicted Rho-independent termination signal downstream of pbp4B is indicated by a lollipop symbol. (B) The nucleotide sequence of the murR-murQ intergenic region of E. coli MG1655 is shown. The murQ transcriptional start sites (PQ1 and PQ2) as well as the murR start site (PR), which were identified in this work, are indicated. Gray boxes highlight the −10/−35 promoter regions relative to PQ1, and open boxes indicate those relative to PQ2 and PR. The hatched box indicates the putative CAP binding site −71.5 bp upstream of PQ1, with the consensus CAP binding motif shown beneath. The inverted repeats (IR1 and IR2), which were identified in this work as constituting MurR binding sites, are indicated. The putative ribosome binding sites (Shine-Dalgarno sequences [SD]) are underlined, and the start codons of murR and murQ are shown (black boxes).

To investigate the regulation of the MurNAc etherase operon, we generated an in-frame deletion of the entire murR gene by homologous gene replacement. The resulting strain TJ103 (ΔmurR) showed no differences in growth rate and cell morphology on rich medium from those of the parental strain MC4100 (data not shown). However, when grown on MMA supplemented with 0.2% MurNAc as the sole source of carbon at 37°C, TJ103 had about a twofold-reduced mean doubling time of 1.9 ± 0.6 h (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) compared to that of MC4100 (3.4 ± 0.3 h) (11). In addition, a sixfold-reduced lag phase was observed for the murR deletion mutant compared to that of the wild type (lag time = 2.0 ± 0.5 h and 11.5 ± 0.8 h determined for TJ103 and MC4100, respectively). Hence, inactivation of murR markedly increases growth on MurNAc, indicating that MurR functions as a repressor of the MurNAc pathway.

Identification of the transcription start sites of murQ and murR.

The transcriptional start sites for murQ and murR were determined by 5′ RACE using mRNA preparations from TJ103 (ΔmurR) or MC4100 (MurR+) cells grown on rich medium (LB) or minimal medium supplemented with MurNAc (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Two start sites (PQ1 and PQ2) were determined for the murQ transcripts, which are located 40 and 32 bases, respectively, upstream of the murQ translation start codon (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). The major transcript of murQ was found to start with an adenine (PQ1), whereas a transcript detected in lower quantities uses thymine as the first base (PQ2), which generally is a less favorable pyrimidine nucleotide for initiation of transcription (24). Only one transcriptional start site, an adenine (PR), was obtained for murR in the 5′ RACE experiment (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). PR lies within the murQ gene, on the complementary strand and 182 bases upstream of the murR translation start codon. The results demonstrated that the murQ and murR promoters are orientated face to face, hence yielding transcripts that overlap by 61 (PQ1-PR) or 53 (PQ2-PR) bases in their 5′ ends.

Determination of the promoter strength.

To evaluate the promoter strength under various growth conditions, we generated E. coli chromosomal transcriptional lacZ fusions in the MurR+ (TJ107; murQ-lacZ/TJ108; murR-lacZ) and ΔmurR (TJ105; murQ-lacZ/TJ106; murR-lacZ) background. These constructs were generated by single-copy insertion into the att site by the lambda InCh technique (5). They contain the whole murR-murQ intergenic sequence carrying the convergent mur promoters, region I (reg I; see Fig. 2A), in either of the two orientations yielding murQ-lacZ (murR-phoA) or murR-lacZ (murQ-phoA) transcriptional fusions. β-Galactosidase activity was measured during early stationary phase (10 h of growth) in cells grown on LB medium (Table 2). In the wild-type background low specific β-galactosidase activity (1.4 mU mg−1) could be detected only in the murQ-lacZ strain (TJ107), indicating low-level expression of murQ during growth in the absence of MurNAc. In the ΔmurR background, which simulates the fully derepressed situation, β-galactosidase activity was detected in both the murQ-lacZ (TJ105) and the murR-lacZ (TJ106) strains. Under these conditions, expression from the murQ promoter appeared to be about sixfold higher than that from the murR promoter, and a 20-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity was determined for murQ-lacZ in TJ105 (ΔmurR) compared to the wild-type background (TJ107), which provides further evidence for MurR acting as the repressor of MurQ. We confirmed the results with transcriptional alkaline phosphatase (phoA) fusions in the same background (inverted orientation of the promoter/operator-containing DNA fragment; data not shown).

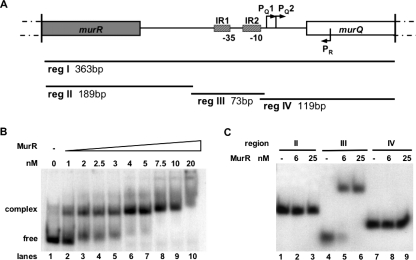

FIG. 2.

MurR binding to full-length and truncated DNA fragments from the murR-murQ intergenic region. (A) Schematic representation of the intergenic region (reg I, 363 bp; drawn to scale) including 108 bp of the 5′ end of murR and the first 92 bp of murQ. The hatched boxes mark the positions of the inverted repeats (IR1 and IR2) locating the proposed DNA binding site for MurR relative to the murQ promoter (−35 and −10) and the start points for murQ (PQ1 and PQ2) and murR transcription (PR). Autoradiograms of EMSA are shown; the assays were performed with 5′-labeled DNA fragments carrying the entire intergenic region (reg I [B]) and truncated DNA fragments as indicated (reg II, reg III, and reg IV [C]). (B) Full-length DNA fragment from the murR-murQ intergenic region (reg I) incubated with increasing amounts of MurR as indicated (lanes 2 to 10). Migration of reg I without repressor protein is shown in lane 1. (C) Comparison of the retardation of DNA fragments from the murR-murQ intergenic region of different sizes upon binding of MurR. Purified protein was added at 6 and 25 nM final monomer concentrations, respectively. Migration of the fragments without repressor protein is shown in lanes 1, 4, and 7. Lanes 1 to 3, reg II; lanes 4 to 6, reg III harboring the predicted MurR binding site; lanes 7 to 9, reg IV. Each sample contained 0.5 μg of polynucleotides [poly(dI-dC)] to avoid unspecific binding, and the complexes were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel.

TABLE 2.

MurR is a transcriptional repressor for murQ expression

| E. coli strain | Relevant genetic background | Sp act of β-galactosidase (mU mg−1)a |

|---|---|---|

| TJ107 | murQ-lacZ | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| TJ108 | murR-lacZ | ND |

| TJ105 | ΔmurR murQ-lacZ | 26.8 ± 1.7 |

| TJ106 | ΔmurR murR-lacZ | 4.3 ± 1.0 |

β-Galactosidase activities (1 unit was defined as 10−6 mol min−1) were measured at early stationary phase (10 h) in cells growing on LB medium. The data represent the means of four independent experiments with the standard deviations. ND, not detectable.

Characterization of the repressor MurR.

To characterize the repressor MurR, we constructed a MurR expression plasmid, overproduced MurR as a C-terminal His6 fusion protein, and purified it to apparent homogeneity by nickel affinity chromatography and gel filtration. Gel filtration and dynamic light scattering were used to analyze the oligomeric form of purified MurR-His6 in a monodisperse solution and determined a molecular mass of 154 ± 2 kDa (gel filtration) or 154 ± 5 kDa (Stokes-Einstein hydrodynamic radius as determined by dynamic light scattering), indicating that MurR is an oligomer in solution (data not shown). If the theoretical molecular mass of 32,223 Da for a MurR-His6 monomer based on its deduced amino acid sequence is taken into account, the gel filtration and dynamic light scattering experiments indicate the presence of either a tetramer (129 kDa) or a pentamer (161 kDa). A pentamer is very untypical for a transcriptional regulator, and we assume that MurR is more likely to form a tetramer in solution; the slightly higher apparent mass could be explained if the shape of the MurR tetramer differs from that of a sphere. The oligomeric form of MurR remained stable for several weeks at 4°C in diluted buffers containing NaCl at a final concentration of at least 300 mM. To avoid unspecific aggregation of concentrated MurR preparations and for purification by gel filtration, we usually applied a buffer containing 1 M NaCl.

Characterization of the MurR operator site.

To investigate DNA binding activity of MurR, we performed EMSA, with protein (oligomeric form) purified by gel filtration and radioactively labeled operator DNA fragments generated by PCR carrying different parts of the murR-murQ intergenic region (reg I to IV; Fig. 2A). The alteration in mobility of the 5′-labeled 363-bp fragment (reg I) by incubation with an increasing amount of MurR is shown in an autoradiogram (Fig. 2B). A 2 nM concentration of MurR was sufficient to shift half of the DNA. We noticed that the reg I fragment did not enter the gel when high amounts of MurR (20 nM; Fig. 2B, lane 10) were added, indicating the formation of higher oligomeric forms of MurR or unspecific binding to the DNA. The intergenic region upstream of the murQ transcription start site PQ1 contains two imperfect inverted repeats (matching bases are underlined), IR1 (5′-AGACTCA A TGATTCC-3′) and IR2 (5′-GGGATATATGATTCC-3′), which both carry a short stretch of eight bases, shown in bold letters. IR1 and IR2 might constitute the regulator binding site. To restrict the MurR binding region, three truncated DNA fragments carrying different parts of the intergenic region (reg II to IV, Fig. 2A) were applied to EMSA (Fig. 2C). reg II contains the 5′ end of murR together with the proximal part of the gene, reg III harbors the inverted repeats illustrated above, and reg IV carries the region upstream of murQ including the first 93 bases of the gene (Fig. 2A). reg III, but not reg II or reg IV, was retarded by binding to MurR as shown in Fig. 2C, which provides evidence that the two inverted repeats within reg III represent MurR binding sites.

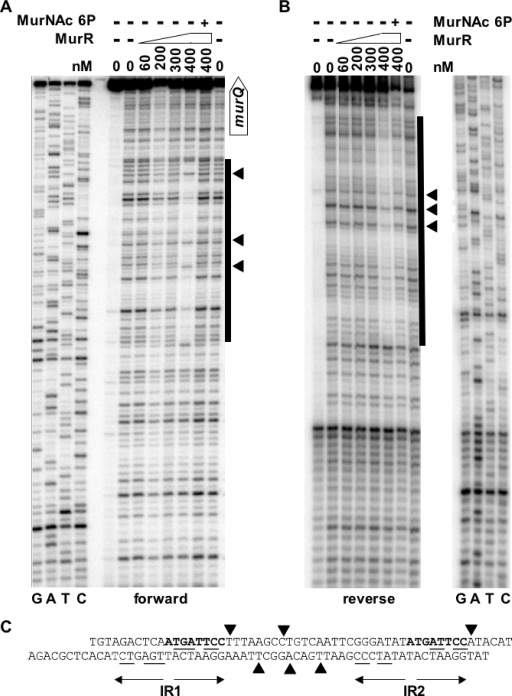

To identify the exact sites of MurR binding, DNase I protection assays were performed with linear DNA carrying the entire murR-murQ intergenic region (reg I; Fig. 2). Increasing amounts of purified MurR were incubated with labeled DNA (forward and reverse strand, Fig. 3A and B, respectively). A large, single DNase I protection site was detected, centered at position −29 (in respect to PQ1) and including the two inverted repeats (IR1 and IR2). Within the protected area sites sensitive for DNase I cleavage were found to coincide with the region that separates the two inverted repeats. The protected region identified by DNase I protection assays and the DNase-sensitive region between the inverted repeats are depicted in Fig. 3C. The results support our model that MurR binds as an oligomer (presumably a tetramer) to the two inverted repeats (each likely bound by one HTH dimer). In this way, MurR covers the −10/−35 promoter elements upstream of the murQ transcription start sites PQ1 and PQ2, thus preventing recruitment of RNA polymerase. It should be noted that the protection patterns of the forward and reverse strands were not exactly the same, indicating that MurR might bind with a slightly displaced orientation, relative to both strands.

FIG. 3.

DNase I protection assay for MurR binding to the murR-murQ promoter/operator region. (A and B) Protection patterns of the forward (A) and reverse (B) strands. Linear radioactively 5′-labeled DNA was incubated with different concentrations of MurR followed by incubation with DNase I; the reaction mixtures were then analyzed on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The lanes labeled with G, A, T, and C show the sequencing ladders (no MurR), and the adjacent lanes show DNA in the absence of DNase I treatment and DNA treated with DNase I and incubated with MurR in increasing amounts, as indicated. DNA protection in the presence of 0.4 μM MurR was abolished by addition of 5 mM MurNAc-6-P. The location of the protected DNA region is indicated by a vertical bar, and solid arrowheads mark the DNase I-sensitive sites within the binding region of MurR. The open arrow labels the position of the start codon of murQ in panel A. (C) Sequence of the region protected by MurR on the forward and the reverse strand. The imperfect inverted repeats (IR1 and IR2) presumably representing the MurR binding region are marked with arrow pairs pointing in opposite directions; matching bases in the repeats are underlined. The short sequence present in both inverted repeats is shown in bold, and solid arrowheads mark the DNase I-sensitive sites within the MurR binding region (as in panels A and B).

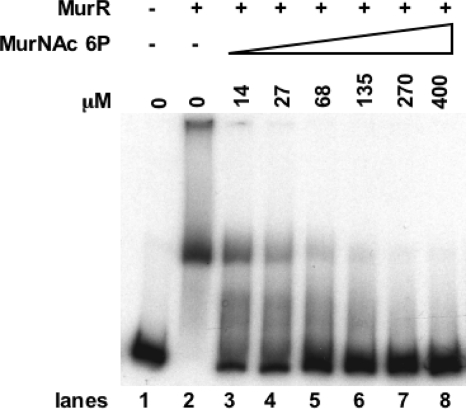

Identification of MurNAc-6-P, the effector of MurR.

MurR carries a so-called sugar phosphate isomerase/sugar phosphate binding (SIS) domain like that of MurQ, which is involved in MurNAc-6-P binding (20). It is therefore reasonable to assume that MurNAc-6-P might also affect DNA binding of MurR. To investigate this, we performed EMSA with the 5′-labeled full-length operator region (reg I) incubated with 30 nM MurR and increasing amounts of MurNAc-6-P. MurNAc-6-P added at a final concentration of 14 μM releases half of MurR from the operator DNA (Fig. 4). Other intermediates of the amino sugar metabolism were also tested, but none influences the MurR-DNA binding; neither GlcNAc-6-P (up to 5 mM final concentration), GlcNAc (9 mM), anhydroMurNAc (0.2 mM), MurNAc (up to 6.82 mM), nor muramyl dipeptide (0.4 mM) had an effect on MurR binding to the operator site (data not shown). Thus, the DNA binding affinity of MurR is modulated specifically by MurNAc-6-P. The phosphosugar had no effect on the oligomerization state of MurR as analyzed by gel filtration of MurR in the presence of 5 mM MurNAc-6-P (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effect of MurNAc-6-P on MurR binding to operator DNA. Autoradiogram of EMSA performed with 5′-labeled full-length DNA fragment (reg I; Fig. 2). Migration of the fragment without repressor protein is shown in lane 1. Operator fragments were incubated with purified MurR at a final concentration of 30 nM (lane 2) and with MurR and increasing amounts of MurNAc-6-P as indicated (lanes 3 to 8). Each sample contains 0.5 μg of unspecific DNA [poly(dI-dC)]. The complexes were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel.

Determination of the role of catabolite repression in the induction of murQ and murR.

The global regulator cAMP-CAP controls the majority of sugar utilization operons, usually acting in conjunction with an operon-specific regulator (8). A putative binding site for the CAP transcriptional regulator (5′-TATGA-N6-TCACA-3′) was found within the murR-murQ intergenic region (as illustrated in Fig. 1B). This site differs at the second position (G-to-A exchange) from the consensus CAP binding motif (5′-TGTGA-N6-TCACA-3′) (14). The distance of the CAP site −71.5 bp upstream of PQ1 is typical for a class I CAP-controlled operon (2) and suggests a CAP-dependent activation of murQ transcription. To test this hypothesis, we first investigated whether biphasic growth could be observed for E. coli MC4100 growing on MMA supplemented with glucose (0.1%) and MurNAc (0.2%) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Under these conditions, MC4100 shows diauxic growth; glucose is metabolized first, followed by the utilization of MurNAc and depletion from the medium as analyzed with the Morgan-Elson assay (data not shown).

To examine the role of cAMP-CAP in the regulation of the murQ operon in vivo, we used merodiploid E. coli mutants carrying chromosomal murQ-lacZ transcriptional fusions in the murR+ (TJ107) and the ΔmurR (TJ105) backgrounds. These constructs contain the whole murR-murQ intergenic sequence carrying the convergent mur promoters and the putative CAP binding site, reg I (Fig. 2A). β-Galactosidase activity, which corresponds to the level of murQ transcription, was measured during exponential and stationary phases in cells grown on MMA glucose and MMA-CAA with or without MurNAc added to the medium (Table 3). Neither in the exponential nor in the stationary phase could β-galactosidase activity be detected in TJ107 (murR+) cells grown on glucose. Hence, murQ expression is repressed in the presence of glucose in the medium (catabolite repression). However, when the glucose medium was supplemented with MurNAc, β-galactosidase activity was detectable in second-exponential-phase cells. The difference in the β-galactosidase activities in the TJ107 strain at the two growth phases can be explained by the utilization of glucose prior to MurNAc and depletion of glucose from the medium upon prolonged culturing (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). When CAA instead of glucose was the carbon source for TJ107, low β-galactosidase activity was detectable (Table 3), in the same range as that for the cells grown on LB (Table 2), indicating cAMP-CAP-dependent activation of murQ transcription. Addition of MurNAc to the culture medium containing CAA increased the transcription levels at the first exponential growth phase 20-fold. β-Galactosidase activity was markedly reduced in cells that have entered the second exponential phase, indicating that MurNAc metabolism, and hence β-galactosidase expression, peaks early in growth and that after 23 h the MurNAc might already be degraded. This is in agreement with our observations that MurNAc is the preferred carbon source relative to CAA and is depleted from the medium first (Morgan-Elson assay; data not shown).

Introduction of a murR deletion (TJ105) results in constitutive murQ-lacZ expression, which was low (4.5 mU mg−1) when glucose was used as the carbon source due to catabolite repression conditions but increased four- to fivefold upon growth on CAA (noncatabolite repression conditions). An increase in β-galactosidase activity in TJ105 cells from stationary phase/second exponential phase grown on glucose or glucose/MurNAc over the activity of those from first exponential phase can be explained by cAMP-CAP stimulating transcription only when glucose (the preferred carbon source) is depleted. The differences in β-galactosidase activity in the stationary phase/second exponential phase of TJ105 cells grown on glucose compared to those grown on glucose/MurNAc, respectively, can be explained by lower catabolite repression when glucose is depleted from the medium or might be due to slow degradation of the β-galactosidase after prolonged incubation. The latter can also explain the reduced activity in stationary-phase TJ105 cells grown on CAA. However, we cannot exclude other factors influencing MurQ expression at late growth phase.

To further evaluate the role of cAMP-CAP in the regulation of murQ transcription, we constructed a crp deletion mutant in the murQ-lacZ background (TJ114). Under noncatabolite repression conditions (MMA, 1% CAA) the crp mutation resulted in four- to fivefold-reduced murQ-lacZ expression (Fig. 5). Interestingly, this effect was observed regardless of whether MurNAc was added to the medium, likely because MurNAc cannot enter the cell, because MurP is not expressed.

FIG. 5.

Influence of catabolite repression and cell wall recycling on murQ-lacZ expression. β-Galactosidase activity was determined at late exponential phase (8.5 h) in cells growing on MMA supplemented with 1% CAA. The activity obtained for strain TJ107 (indicated as wild type [wt]) was set to 1 (3.75 ± 0.25 mU mg−1). The relative rates of β-galactosidase activity in strains with deletions of crp (TJ114), encoding CAP; murR (TJ105); murQ (TJ117); murP (TJ119); anmK (TJ123), encoding the anhydroMurNAc kinase involved in cell wall recycling; or both murP and anmK (TJ126) are depicted in the absence of MurNAc (light gray bars) or in the presence of 0.1% MurNAc in the medium (dark gray bars). The data represent the means of three independent experiments with the standard deviations.

Binding of CAP to the murQ operator region.

The CAP binding site (adjacent to the MurR sites) within the murQ operator region (murO) differs from the consensus motif in the second position as depicted above and also shows no symmetry in the 6 bp between the motifs (Fig. 1B). The affinity of CAP for the binding site, however, is correlated with the degree of symmetry in the complete site (21). To determine the affinity of CAP for the binding site, we performed EMSA. Increasing amounts of purified CAP were incubated with the 5′-labeled operator fragment (reg I) as shown in the autoradiogram (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). At a considerably high CAP concentration of 210 nM, half of the DNA is shifted. This indicates a rather low affinity of CAP for the binding site, compared with the lac site (one of the strongest CAP binding sites), where half of the DNA is shifted at 5 nM (23). CAP binding to an operator site similar to the one within murO was reported to be about 50% reduced in affinity compared to the CAP site within the lac operator (21). The C-terminal His tag fused to the CAP for easy purification should not influence DNA binding but may influence affinity for cAMP. EMSA with CAP and MurR indicated that the two proteins could bind simultaneously to the operator region (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

The role of cell wall recycling and MurNAc uptake in the induction of murQ.

In TJ107 (murQ-lacZ) cells grown on CAA, which represents cAMP-CAP-activated conditions, murQ expression is about fivefold higher than in the Δcrp strain (TJ114). The basal level of murQ expression was not affected by either a deletion in murP (TJ119), in anmK (TJ123) (the gene encoding the anhydroMurNAc kinase), or both (TJ126) (Fig. 5). However, elevated murQ transcription levels were reached in a murQ deletion strain (TJ117). This strain accumulates MurNAc-6-P from recycling of the endogenous cell wall, and MurR gets detached from the operator. Expression of murQ is not further increased in TJ117 (ΔmurQ) by MurNAc in the medium. In TJ107 (and the ΔanmK strain TJ123), however, MurNAc in the medium increases the murQ expression to a level similar to that of the murQ mutant grown on CAA and almost reaching the expression levels of a murR deletion mutant (TJ105).

DISCUSSION

The MurNAc etherase MurQ of E. coli is involved in two catabolic pathways. These are the utilization of external MurNAc as the sole source of carbon and the recycling of anhydroMurNAc released from the endogenous cell wall during growth (19, 40). In this study we identified a specific transcriptional repressor of the MurNAc etherase that is divergently transcribed from murQ and encoded by murR (formerly yfeT). MurR belongs to the poorly characterized RpiR/AlsR family of transcriptional regulators, whose members contain two domains, a highly conserved N-terminal HTH domain and a C-terminal SIS (sugar phosphate isomerase/sugar phosphate binding) domain (3). The HTH domain is one of the most widely used DNA binding domains in prokaryotes (17) and in general functions as a homodimer to allow binding of both half-sites of a symmetric (palindromic) DNA motif (27, 29). We showed that MurR binding to two adjacent imperfect repeats within the murR-murQ intergenic region (murO) interferes with transcription from the murQ promoter. Dynamic light scattering and gel filtration experiments demonstrated that MurR forms a stable multimer, which might be either a tetramer or a pentamer. The formation of a MurR tetramer would fit with our model that the two adjacent MurR operator sites are each bound by a MurR dimer via their HTH domains. The high affinity of MurR for murO (Kd [dissociation constant] of 2 nM) might be explained by two MurR homodimers acting synergistically when binding to the two adjacent operator sites; additional work, however, is required to support this hypothesis. Oligomerization of homotetrameric regulators, e.g., the LysR-like regulator CbnR of Ralstonia eutropha (26), is mediated by the regulatory domain. An obvious candidate for a regulatory (oligomerization) domain in MurR is the C-terminal SIS domain (3). It is also present in MurQ (30% identical to MurR in a stretch of 130 amino acids constituting the SIS domain) and most likely involved in MurNAc-6-P binding and dimerization of this protein (20): SIS domains constitute conserved binding folds to accommodate sugar phosphates (3). In general, two SIS domains are required to build up two symmetrical sugar phosphate binding pockets. Amino acid residues from different parts of the two SIS domains contribute to the sugar phosphate binding site and complement each other. Hence, polypeptides carrying only one SIS domain, like MurQ and MurR, need to be arranged as homodimers, in order to accommodate a sugar phosphate (20). We have shown by EMSA and DNase I protection and transcriptional fusion assays that MurNAc-6-P specifically modulates DNA binding activity and functions as the inducer of the MurNAc operon. Upon binding of MurNAc-6-P only a slight conformational change in MurR might be induced due to the rearrangement of the SIS domains and not an alteration of the state of oligomerization, since no change in the size of MurR (based on gel filtration experiments) was observed in the presence of MurNAc-6-P. A concentration of about 14 μM of MurNAc-6-P was shown to be sufficient to release half of the MurR from the DNA (Fig. 2). The intracellular concentration of MurNAc-6-P that accumulates during cell wall recycling in an etherase deletion mutant was calculated to range between 2 and 7 mM (19, 40). Indeed, murQP expression is highly induced in a ΔmurQ strain (Fig. 5), regardless of whether MurNAc is present in the medium. In wild-type E. coli, however, MurQ readily degrades MurNAc-6-P and it usually does not accumulate from cell wall recycling metabolism. Accordingly, a defect in cell wall recycling by deletion of anmK (TJ123) has no significant effect on murQ-lacZ transcription compared to that of the wild type (TJ107) as depicted in Fig. 5.

Low β-galactosidase activities determined with murQ and murR-lacZ fusions indicate the presence of rather weak promoters (Table 2) that were found to significantly deviate from the consensus sequence of the sigma 70-dependent promoter elements. Usually there is a good correlation between the promoter strength and the degree of identity (7). The −35/−10 regions of the murQ (PQ1, 5′-CTTTAA-18 bp-TATGAT-3′; PQ2, 5′-CTGTCA-18 bp-CATACA-3′) and the murR (5′-GTCAAT-18 bp-TCGAGC-3′) promoters differ from the consensus motif (−35, 5′-TTGACA-3′; −10, 5′-TATAAT-3′) in about half the positions (Fig. 1B), explaining the low transcription rates observed. We showed that the murR and murQ promoters are orientated convergently (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), leading to a partial (61- or 53-bp) 5′ overlap of the complementary transcripts. This promoter organization is rather unusual; only about 1% of the promoters predicted from the sequence of the E. coli MG1655 chromosome (54 of 4,462 promoters in total) are nonoverlapping face-to-face promoters, placed 40 to 200 bp apart (9, 35). A convergent promoter organization holds the potential for regulation by transcriptional interference and is commonly found in extrachromosomal elements such as insertion sequences, transposable elements, plasmids, and bacteriophages (9). The convergent (face-to-face) promoter arrangement might facilitate the flexibility in the adjustment of murQ and murR expression to growth conditions. While MurR inactivates and cAMP-CAP activates murQ expression, both regulators inactivate murR expression, presumably by acting as a roadblock for RNA polymerase. Indeed, in the absence of murR, murR-lacZ is increased to significant levels (Table 2). In the absence of MurNAc in the medium and hence low expression levels, cAMP-CAP strongly influences murQ expression. In consequence, low or even absent murQP expression was detected at catabolite repression conditions (growth on glucose or deletion of crp; Table 3 and Fig. 5). Even though the affinity of cAMP-CAP for murO is weak, as shown by EMSA (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), the transcription rate of murQ was increased to a low but significant level in the absence of glucose in the medium (Table 3). The regulatory influence of catabolite repression on the transcription of the murQ operon is also indicated by the observation of diauxic growth of E. coli on minimal medium with glucose/MurNAc (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

Figure 6 summarizes our current understanding of the regulation of the murQ operon. The two transcription factors, MurR and cAMP-CAP, act together in controlling repression and inducing the etherase operon. Normally, the expression of murQP is repressed by the high-affinity binding of the MurR to the operator region (murO), which harbors two inverted repeats (IR1 and IR2) in the murQ promoter region upstream of the murQ transcription start sites (PQ1 and PQ2). Low but significant expression of murQP results from transcription from the weak and cAMP-CAP-activated promoter, whereas cAMP-CAP and MurR both repress murR expression, possibly by generating a roadblock for RNA polymerase. During recycling of the endogenous cell wall only low amounts of MurNAc-6-P are generated in the cytoplasm, which do not lead to significant derepression of MurR. Under these conditions the transcription rate is still low, since MurQ readily degrades the inducer, which enables MurR to bind to the operator. Hence, low promoter strength in combination with repression of murR expression adjusts expression of MurQ at a low level, just sufficient for continuous cell wall recycling.

FIG. 6.

Illustration of the proposed regulation network of MurNAc catabolism. In the operator region (murO, lower part), hatched boxes mark the two inverted repeats (IR1 and IR2) upstream of murQ. The cAMP-CAP class I site upstream of murQ is shown as a gray-shaded box centered at −71.5 bp, relative to the PQ1 transcription start site. Horizontal arrows indicate the transcription start sites (PQ1/PQ2 and PR). For details, see the text.

The internal level of the inducer MurNAc-6-P needs to exceed a critical concentration before murQP transcription reaches a level sufficient for growth on MurNAc. Indeed, overexpression of MurQ from plasmid even decelerates growth on MurNAc (data not shown), and an extensive lag phase is observed for E. coli grown on MurNAc (11). However, accumulation of MurNAc-6-P (e.g., in a murQ deletion strain or upon vigorous uptake of MurNAc by the PTS) induces murQ (and therewith murP) transcription. When the cells grow on MurNAc as the sole source of carbon, a strong transcription of murQP is necessary, which requires the full induction and depends not only on derepression of MurR but also on binding of the cAMP-CAP complex to the class I site upstream of PQ1 (−71.5 bp). Transcription levels as high as those in a murR deletion, however, are barely reached. This might be due to catabolite self-repression. Phosphorylated EIIAGlc activates adenylate cyclase, the enzyme that generates cAMP. Since the PTS component is also required for phosphorylation of MurNAc and transport by the MurNAc-specific permease MurP, depletion of the EIIAGlc-P pool due to MurNAc uptakes lowers the level of cAMP-CAP.

The model for regulation of the MurNAc catabolism in E. coli might serve as a paradigm for other bacteria. We found that MurR-like regulators are present in several bacterial species, mostly together with an ortholog of MurQ, which implies that a MurNAc/anhydroMurNAc catabolic pathway and a conserved regulatory mechanism exist in many bacteria (20).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Winfried Boos, in whose laboratory this study was carried out, for his continuous support. We also thank Alexander Brosig (AG Welte/Diederichs) for help with the dynamic light scattering, Markus Wieland (AG Hartig) for help with the footprint analyses, and Erika Oberer-Bley (AG Deuerling) for critical advice on the manuscript.

Financial support from the Universitätsgesellschaft Konstanz and the ZWN (Zentrum für den wissenschaftlichen Nachwuchs) of the University of Konstanz for T.J. is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by a research grant and a Heisenberg stipend from the Deutsche Forschungsemeinschaft to C.M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 August 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlung, T., A. Nielsen, L. J. Rasmussen, L. J. Nellemann, and F. Holm. 1991. A versatile method for integration of genes and gene fusions into the λ attachment site of Escherichia coli. Gene 10711-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnard, A., A. Wolfe, and S. Busby. 2004. Regulation at complex bacterial promoters: how bacteria use different promoter organizations to produce different regulatory outcomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7102-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bateman, A. 1999. The SIS domain: a phosphosugar-binding domain. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2494-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 2771453-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd, D., D. S. Weiss, J. C. Chen, and J. Beckwith. 2000. Towards single-copy gene expression systems making gene cloning physiologically relevant: lambda InCh, a simple Escherichia coli plasmid-chromosome shuttle system. J. Bacteriol. 182842-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busby, S., and R. H. Ebright. 1994. Promoter structure, promoter recognition, and transcription activation in prokaryotes. Cell 79743-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busby, S., and R. H. Ebright. 1999. Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J. Mol. Biol. 293199-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callen, B. P., K. E. Shearwin, and J. B. Egan. 2004. Transcriptional interference between convergent promoters caused by elongation over the promoter. Mol. Cell 14647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casadaban, M. J. 1976. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104541-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl, U., T. Jaeger, B. T. Nguyen, J. M. Sattler, and C. Mayer. 2004. Identification of a phosphotransferase system of Escherichia coli required for growth on N-acetylmuramic acid. J. Bacteriol. 1862385-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutscher, J., C. Francke, and P. W. Postma. 2006. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70939-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebright, R. H., Y. W. Ebright, and A. Gunasekera. 1989. Consensus DNA site for the Escherichia coli catabolite gene activator protein (CAP): CAP exhibits a 450-fold higher affinity for the consensus DNA site than for the E. coli lac DNA site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1710295-10305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodell, E. W. 1985. Recycling of murein by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 163305-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Höltje, J.-V. 1998. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62181-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huffman, J. L., and R. G. Brennan. 2002. Prokaryotic transcription regulators: more than just the helix-turn-helix motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs, C., L. J. Huang, E. Bartowsky, S. Normark, and J. T. Park. 1994. Bacterial cell wall recycling provides cytosolic muropeptides as effectors for β-lactamase induction. EMBO J. 134684-4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaeger, T., M. Arsic, and C. Mayer. 2005. Scission of the lactyl ether bond of N-acetylmuramic acid by Escherichia coli “etherase.” J. Biol. Chem. 28030100-30106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaeger, T., and C. Mayer. 2008. N-Acetylmuramic acid 6-phosphate lyases (MurNAc etherases): role in cell wall metabolism, distribution, structure, and mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65928-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen, C., A. M. Gronenborn, and G. M. Clore. 1987. The binding of the cyclic AMP receptor protein to synthetic DNA sites containing permutations in the consensus sequence TGTGA. Biochem. J. 246227-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, C., S. Song, and C. Park. 1997. The d-allose operon of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1797631-7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolb, A., A. Spassky, C. Chapon, B. Blazy, and H. Buc. 1983. On the different binding affinities of CRP at the lac, gal and malT promoter regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 117833-7852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, J., and C. L. Turnbough, Jr. 1994. Effects of transcriptional start site sequence and position on nucleotide-sensitive selection of alternative start sites at the pyrC promoter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1762938-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 26.Muraoka, S., R. Okumura, N. Ogawa, T. Nonaka, K. Miyashita, and T. Senda. 2003. Crystal structure of a full-length LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CbnR: unusual combination of two subunit forms and molecular bases for causing and changing DNA bend. J. Mol. Biol. 328555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pabo, C. O., and R. T. Sauer. 1992. Transcription factors: structural families and principles of DNA recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 611053-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park, J. T. 2001. Identification of a dedicated recycling pathway for anhydro-N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetylglucosamine derived from Escherichia coli cell wall murein. J. Bacteriol. 1833842-3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Rueda, E., and J. Collado-Vides. 2000. The repertoire of DNA-binding transcriptional regulators in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 281838-1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plumbridge, J., and A. Kolb. 1991. CAP and Nag repressor binding to the regulatory regions of the nagE-B and manX genes of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 217661-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plumbridge, J. A. 1990. Induction of the nag regulon of Escherichia coli by N-acetylglucosamine and glucosamine: role of the cyclic AMP-catabolite activator protein complex in expression of the regulon. J. Bacteriol. 1722728-2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poulsen, T. S., Y.-Y. Chang, and B. Hove-Jensen. 1999. d-Allose catabolism of Escherichia coli: involvement of alsI and regulation of als regulon expression by allose and ribose. J. Bacteriol. 1817126-7130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowley, D. L., and R. E. Wolf. 1991. Molecular characterization of the Escherichia coli K-12 zwf gene encoding glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 173968-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schönert, S., S. Seitz, H. Krafft, E. A. Feuerbaum, I. Andernach, G. Witz, and M. K. Dahl. 2006. Maltose and maltodextrin utilization by Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1883911-3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shearwin, K. E., B. P. Callen, and J. B. Egan. 2005. Transcriptional interference—a crash course. Trends Genet. 21339-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorensen, K. I., and B. Hove-Jensen. 1996. Ribose catabolism of Escherichia coli: characterization of the rpiB gene encoding ribose phosphate isomerase B and of the rpiR gene, which is involved in regulation of rpiB expression. J. Bacteriol. 1781003-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiess, C., A. Beil, and M. Ehrmann. 1999. A temperature-dependent switch from chaperone to protease in a widely conserved heat shock protein. Cell 97339-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Studier, F. W., and B. A. Moffat. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. Mol. Biol. 189113-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uehara, T., and J. T. Park. 2002. Role of the murein precursor UDP-N-acetylmuramyl-l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-meso-diaminopimelic acid-d-Ala-d-Ala in repression of β-lactamase induction in cell division mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1844233-4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uehara, T., K. Suefuji, T. Jaeger, C. Mayer, and J. T. Park. 2006. MurQ etherase is required by Escherichia coli in order to metabolize anhydro-N-acetylmuramic acid obtained either from the environment or from its own cell wall. J. Bacteriol. 1881660-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uehara, T., K. Suefuji, N. Valbuena, B. Meehan, M. Donegan, and J. T. Park. 2005. Recycling of the anhydro-N-acetylmuramic acid derived from cell wall murein involves a two-step conversion to N-acetylglucosamine-phosphate. J. Bacteriol. 1873643-3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vega, D., and J. A. Ayala. 2006. The DD-carboxypeptidase activity encoded by pbp4B is not essential for the cell growth of Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 18523-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto, H., M. Serizawa, J. Thompson, and J. Sekiguchi. 2001. Regulation of the glv operon in Bacillus subtilis: YfiA (GlvR) is a positive regulator of the operon that is repressed through CcpA and cre. J. Bacteriol. 1835110-5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu, D., H. M. Ellis, E. C. Lee, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and D. L. Court. 2000. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 975978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.