Abstract

After infection with RML murine scrapie agent, transgenic (tg) mice expressing prion protein (PrP) without its glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor (GPI−/− PrP tg mice) continue to make abundant amounts of the abnormally folded disease-associated PrPres but have a normal life span. In contrast, all age-, sex-, and genetically matched mice with a GPI-anchored PrP become moribund and die due to a chronic progressive neurodegenerative disease by 160 days after RML scrapie agent infection. We report here that infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice, although free from progressive neurodegenerative disease of the cerebellum and extrapyramidal and pyramidal systems, nevertheless suffer defects in learning and memory, long-term potentiation, and neuronal excitability. Such dysfunction increases over time and is associated with an increase in gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibition but not loss of excitatory glutamate/N-methyl-d-aspartic acid. Enhanced deposition of abnormally folded infectious PrP (PrPsc or PrPres) in the central nervous system (CNS) localizes with GABAA receptors. This occurs with minimal evidence of CNS spongiosis or apoptosis of neurons. The use of monoclonal antibodies reveals an association of PrPres with GABAA receptors. Thus, the clinical defects of learning and memory loss in vivo in GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie agent may likely involve the GABAergic pathway.

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies represent the only known infectious protein folding disease (8, 29, 30). In these fatal neurodegenerative disorders of humans and animals, the normal cellular prion protein (PrPc or PrPsen), which is sensitive to protease K treatment, is misfolded from its predominant α-helical form into a β-sheath-enriched structure that becomes resistant to protease K treatment (PrPsc or PrPres) (8, 29, 30). No diagnostic marker that signals the presence of infectivity in prion disease has been found. Instead, a firm diagnosis rests on identifying the characteristic neuropathologic changes, usually postmortem, in combination with immunohistochemically identified manifestations of abnormal PrPres on brain sections and on isolation from brain tissues tested by Western blotting.

In humans, the initial clinical indicators of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) include memory loss, behavioral changes and progressive dementia, and these signs resemble those in sheep infected in the wild with scrapie agent, in deer with chronic wasting disease, and in mice experimentally infected with scrapie agent (29). Following these early signs are marked manifestations of neurodegenerative disease, e.g., involving the cerebellum (ataxia or tremors) as well as the extrapyramidal (involuntary tremors, poverty of movement, or rigidity) and pyramidal (weakness or paralysis) systems.

The precise molecular and neuropharmacologic events underlying the early onset of these behavioral and memory dysfunctions are unclear. Further, in animal models the interval between deposition of large amounts of PrPres and clinical manifestations of neurodegeneration leading to death is often too brief for any long-term kinetic analysis of the progression of neurobehavioral breakdown or diminished learning/memory functions. The recent availability of the GPI−/− PrP transgenic (tg) mice (9), i.e., tg mice lacking the glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor, provides an opportunity to evaluate behavior and memory dysfunction over a prolonged period of time while PrPres deposits continuously accumulate in the absence of clinical neurodegeneration; such mice live for 600 to 700 days. Further, the location of cellular PrP primarily to synaptic regions and nerve processes, as determined by cell fraction studies, in vitro culture experiments, in vivo immunohistochemical analysis by light and high-resolution electron microscopy, and use of green fluorescent protein-tagged PrP tg mice (1, 2, 11, 14), suggest a function for PrP in neural transmission. Since we know that a balance between the excitatory glutamate/N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) pathway and the inhibitory gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathway is a major factor in regulating synaptic transmission, identifying the function and expression of these pathways in the GPI−/− PrP tg model would be of interest.

Attempts to characterize learning and memory in PrP knockout mice have yielded variable results (27, 31, 36). However, the recent use of PrP knockout mice with backgrounds that were genetically equivalent indicated that their defect in cognitive learning was corrected by reconstitution of the PrP gene in neurons but not astrocytes; for this work, cell-specific promoters and genetic engineering were applied (13, 32). Knockout of the PrP gene in brains of adult mice resulted in minimal neurodegeneration, suggesting that responses critical to neuronal function are not lost in this situation (24, 36). Further, administering antibodies to PrPsen focally into the central nervous systems (CNS) of mice not infected with scrapie agent caused neuronal injury, suggesting that aggregation of PrPsen on the cellular membrane (presumably during disease caused by PrPres) signals a neuronal pathway leading to injury (34).

The sum of these observations combined with our findings that scrapie agent-infected (scrapie-infected) tg mice in which anchored PrP is removed from the neuronal membrane still form the folded PrP that incites disease and the manufacturing of infectious material but not overt clinical disease (9, 35) suggests the following outcome: PrP via an excitatory or inhibitory signaling pathway on the neuronal membrane could promote normal PrP function, whereas overstimulation of PrP caused by aggregation with PrPres presumably induces disease.

For this report we took advantage of the ability to separate PrPres buildup from chronic progressive CNS disease in scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice. The continuous accumulation of abnormally folded infectious PrP in the CNS throughout the life span of these animals in the absence of overt neurologic disease positioned us to study the effect of PrPres deposits on learning and memory as well as their influence on the excitatory and inhibitory neuronal pathways. We found that scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice suffered marked defects in learning and memory accompanied by severe loss in neuronal transmission as well as long-term potentiation (LTP) that increased over time. Further, in mechanistic terms, we noted that these defects were associated with the inhibitory GABAergic pathway but not the excitatory glutamate/NMDA pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Scrapie inoculation of mice.

tg mice lines 23 and 44, lacking a GPI anchor (GPI−/− PrP tg mice), were created and genotyped as described previously (9). When infected with murine scrapie, these mice developed PrPres amyloid deposits and infectious PrP material but not clinical neurodegenerative disease. C57BL/6 (wild-type) mice (obtained from the Rodent Breeding Colony at The Scripps Research Institute) were used for infectivity studies and as controls. Infection was induced by inoculating tg and wild-type mice intracerebrally at 6 weeks of age with 30 μl of a 1% suspension of brain tissue from mice infected with RML (Chandler) scrapie. The inoculum contained 0.7 to 1.0 × 106 50% infective dose units of infectious scrapie agent.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry.

Brains were fixed in a neutral buffered 4% formaldehyde solution for 3 to 5 days, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-μm sections using a Leica microtome. Slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated in xylene and alcohol rinses, followed by immunohistochemical staining as reported previously (9, 35). Briefly, slides were autoclaved for 15 min at 20 lb/in2 and 120°C for retrieval of PrPres antigen. Samples were blocked in 2% bovine serum albumin and stained either for PrPres using 3 μg/ml D13 (35) primary antibody or for GABAA receptor (GABAA R) β chain primary antibody. After an overnight incubation at 4°C or a 30-min incubation at room temperature, slides were rinsed with buffer and stained with secondary biotinylated goat anti-human or goat anti-rabbit antiserum diluted 1/200 for detection of D13 and GABAA R β chain, respectively. Streptavidin-conjugated rhodamine or horseradish peroxidase (HRP) followed by Ventana aminoethylcarbazol was used for immunofluorescence or light microscopy, respectively. Amyloid staining employed 1% (wt/vol) of Thioflavin S (MP Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA) in 50% ethanol. Slides were rinsed in twice in 50% ethanol and twice in water prior to mounting and coverslipping. The staining of PrPres and amyloid was observed using an Axiovert S100 (Zeiss) microscope.

Behavior: cued version of the Barnes circular maze.

Here we used a modified form of the Barnes circular maze test (3, 13), in which mice learn to escape through a tunnel by recognizing a target cue that leads to the escape tunnel during sequential daily testing periods. This test differs from the standard Barnes test (3) in that the target cue is located behind the escape hole (13). Briefly, the circular maze consisted of an acrylic disk 75 cm in diameter, 0.5 cm thick, and elevated about 55 cm above the floor. Twenty holes, 5.0 cm in diameter, were placed 5.0 cm from the perimeter, and a black Plexiglas escape tunnel (7.5 by 9.0 cm) was placed under one of the holes. White noise (about 90 dB) and bright ambient light (100 W, 60 cm above the center of the acrylic disk) were used as negative stimuli. The apparatus was located in a procedure room where several visual cues (a white circle in the middle of a black square, a black diamond, and a black bar) were placed on the wall surrounding the circular maze. Prior to testing, the animals were placed in the blind escape tunnel for 4 min for habituation to the maze and then put in a cylindrical chamber in the center of the circular maze. After 10 s, the chamber was removed by using a pulley system and the mice were allowed to explore freely to find the hole with the escape tunnel. A video camera was secured at 70 cm above the platform surface, and two “blinded” experimenters collected behavioral data for all mice tested.

The escape tunnel's location varied randomly from session to session and a visual cue was located directly behind the hole with the escape tunnel. During the habituation period and between all test sessions, the maze and escape tunnel were cleaned with 10% alcohol to remove odor cues (13). The following items were measured in each trial: (i) the latency to start of exploration, which is the time interval (in seconds) between removal of the cylindrical chamber and the animal's moves from the platform's center; (ii) the time to find the escape tunnel, defined as the time between moving from the center of the platform and entering the escape tunnel; (iii) the number of errors, defined as searching holes without the escape tunnel; (iv) the first hole explored upon leaving the center of the platform; and (v) the search strategy, i.e., random, serial, and cued search strategies. The random search strategy involved continuous center crossings exploring incorrect holes and the edge of the platform until the mouse found the hole leading to the escape tunnel. The serial strategy involved a more systematic behavior in which the mouse reached the platform's edge and searched every hole or every other hole in a clockwise or counterclockwise direction until finding the hole leading to the escape tunnel. The cued search strategy was the quickest way to escape, since the animal used cues to find the target hole. The criteria for determining the use of a cue strategy were that the first hole explored was located within two holes from the escape tunnel (cue field) and that escape followed finding the target hole. Any animal that reached the spatial field and then explored holes that were not part of the cue field was scored as not using the cue search strategy. All animals were tested 1 h after the onset of darkness (7:00 p.m.). A trial session ended when the mouse entered the hole leading to the escape tunnel or when 300 s elapsed, whichever occurred first. A total of 42 trials (two trials per day, with each trial separated by 20 min) were performed on consecutive days.

Electrophysiological recording.

For determination of auditory, visual, and brain stem evoked potentials, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (induction, 4 to 5%; maintenance, 1.0% ± 0.2%) and placed into a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Body temperature was monitored and maintained at 37 ± 0.1°C by a feedback-regulated heating pad. A Grass clinical photostimulator model PS 22A was used to deliver a flash (100 flashes of 0.1-ms duration, 16 intensity and 1/s frequency) to generate visual evoked potentials. Mirrors were placed on the walls of the recording cage to ensure binocular stimulation. Auditory evoked potentials (AEPs) were obtained by a condensation stimulation produced by clicks with the following characteristics: for cortical AEPs, 100 clicks of 0.1-ms duration, 70-dB sound pressure level, and 1/s; for brain stem AEPs, 1,024 clicks and 10/s. Software from National Instruments (LabView, Austin, TX) was used to generate the stimuli and to collect the data.

After behavioral studies and evoked potential studies, infected and uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg mice were divided randomly in two groups for electrophysiological studies. In one group the dentate gyrus (DG) was tested, and in the second group the medial prefrontal cortex was tested.

Procedures for electrophysiological recording in the DG.

In the same anesthetized preparation, population spikes, paired-pulse (PP) curves, and LTP were elicited in the granular layer of the DG as described previously (16). Briefly, the skull was exposed and holes were drilled to accommodate stereotaxic placement of electrodes. The dura was opened over the recording area to facilitate positioning of a micropipette. Microelectrodes were stereotaxically oriented into the granular layer of the DG in the septal pole of the dorsal hippocampus (coordinates, 2.0 mm posterior and 1.0 mm lateral relative to bregma; 1.4 to 1.8 mm ventral from dura) (28). Extracellular evoked field potential activity was recorded using single 3.0 M NaCl-filled micropipettes (5 to 10 MΩ; 1 to 2 μs internal diameter). Field potentials were elicited in the DG by stimulation of the perforant path (0.4 to 1.5 mA; 0.10-ms duration; frequency, 0.05 Hz [one stimulus every 30 s]) with insulated, bipolar stainless steel (130-μm) electrodes located in the angular bundle (coordinates, 3.6 mm posterior and 2.8 mm lateral relative to bregma; 2.0 to 2.5 mm ventral from dura) (28). A stimulus-response curve (threshold, half-maximum, and maximum) was determined for each electrophysiological preparation. The intensity of stimulation used to generate PP curves and LTP was set at the half-maximum level of stimulation. We used a PP stimulation protocol with interstimulus intervals ranging from 10 to 360 ms. To induce LTP, baseline activity was recorded for 10 min and then three high-frequency conditioning stimulus (HFS) trains (each consisting of five pulses at 400 Hz) were delivered and population spike amplitudes recorded for 60 min post-HFS.

Procedures for electrophysiological recording in the medial prefrontal area.

The dura was opened over the recording area to facilitate positioning of the micropipette. Microelectrodes were stereotaxically oriented into the medial dorsal thalamic nucleus (0.8 mm posterior to bregma and 0.3 mm lateral to midline) and the medial prefrontal cortex (2.4 mm anterior to bregma and 0.4 mm lateral to midline) at a location generating a maximum amplitude of the prefrontal field potential (18). Extracellular evoked field potential activity was recorded using single 3.0 M NaCl-filled micropipettes (5 to 10 MΩ; 1 to 2 μs internal diameter). Prefrontal field potentials evoked by single-pulse thalamic stimulation (0.1-ms rectangular biphasic pulses) were sent to an amplifier (gain, 1000×; band-pass, 1 to 10 kHz). The stimulus intensity was chosen (from the baseline input-output curves, 60 to 600 μA) as that which produced a response amplitude of ∼60 to 70% of the maximal level. To induce prefrontal LTP, baseline activity was recorded for 10 min, and then we evaluated the effects of HFS of the medial dorsal thalamic nucleus (10 trains, 10 s apart, of 50 pulses at 250 Hz) on prefrontal synaptic excitability.

Immunoprecipitation.

Brain tissues were placed in 2-ml polypropylene screw cap tubes (Biospec Products Inc., Bartlesville, OK) filled up to 25% with sterilized glass beads (1.0-mm-diameter beads; Biospec Products Inc.) containing 1 ml sterile 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) with 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC) (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Tubes were placed into the Mini Beadbeater 8 (Biospec Products Inc.) and homogenized for 1 min. Subsequently, 500-μl portions of homogenates were transferred into sterile 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 × g to remove debris. Supernatants were incubated with 5 μg of either D13 monoclonal antibody (for PrP) or mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as a negative control overnight at 4°C. Forty microliters of protein A-agarose (Millipore) was added for the final 2 h. Complexes were collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 5 min). Immune complexes were washed five times with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing PIC, eluted by boiling in 25 μl of reducing sample buffer, and processed for Western blot analysis. Samples were run on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels; gels were blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% powdered skim milk in sterile water. GABAA R β was detected by addition of mouse or rabbit anti-GABAA R β antibody (9, 35) to membranes and incubation overnight at 4°C. Membranes were rinsed with buffer and stained with secondary HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse or rabbit antiserum diluted 1/20,000 (9). Bands were detected using either the Pico or Phemto chemiluminescent detection kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) (35).

To precipitate GABAA R and probe for PrP, we followed the same procedure with the changes noted. Briefly, brain tissue was placed in 2-ml polypropylene screw cap tubes filled 25% with sterilized glass beads containing 1 ml sterile 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) with 1% NP-40, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and PIC. The tubes were placed into a Mini Beadbeader 8 and homogenized for 1 min, and then 500-μg portions of homogenates were transferred to sterile 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged for 10 min. at 1,000 × g to remove debris. Supernatants were incubated with 5 μg of either GABAA R β subunit 1, 2, or 3; GABAA R α5 subunit (Millipore); or mouse IgG as a negative control overnight at 4°C. Protein A-agarose (40 μl) was added for the final 2 h. Complexes were collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 5 min.). Immune complexes were washed five times with TBS containing PIC, eluted by boiling in 25 μl of reducing sample buffer, and processed for Western blot analysis. For the detection of PrPres, boiled samples were collected and centrifuged at 70,000 × g for 2 h at 10°C in a Beckman TL-100 ultracentrifuge using a TLA 100.3 rotor. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of sterile water (1 ml/200 mg starting tissue), sonicated until disrupted using a Sonic Dismembrator 60 at setting 1 (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL), and digested with proteinase K (25 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.1 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and cooling on ice for 15 min. After centrifugation at 70,000 × g for 1 h at 10°C, pellets were resuspended in 25 μl sample buffer, sonicated, and boiled for 5 min. All samples were run on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were blotted onto PVDF membranes and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% powdered skim milk in sterile water. PrP was detected by adding human anti-PrP antibody D13 (recognizing amino acids [aa] 96 to 106) (3 μg/ml) to membranes and incubating overnight at 4°C. Membranes were rinsed with buffer and stained with secondary HRP-conjugated goat anti-human antiserum diluted 1/20,000 for detection of PrP. Bands were detected using either the Pico or Phemto chemiluminescent detection kit.

This procedure was modified when PrPres-specific reagent was used initially for coimmunoprecipitation. Briefly, whole brains from scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice were homogenized at 10% (wt/vol) in TBS (0.05 M Tris, 0.2 M NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 1% Triton X-100, diluted in an equal volume of TBS, and then rehomogenized and sonicated. Homogenates were clarified at 500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. A portion of clarified prion-infected homogenate was digested with proteinase K (50 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was added to all samples to a final concentration of 2 mM. For each immunoprecipitation, human IgG 136-158 (26, 33) or b12 (7) at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml was incubated for 2 h at room temperature with an aliquot of brain homogenate containing ∼1 mg of total protein in a reaction mixture adjusted to a final volume of 500 μl with assay buffer (TBS containing 1% Triton X-100). Tosyl-activated paramagnetic beads coupled to polyclonal rabbit anti-human IgG F(ab′)2 were added to the antibody-homogenate mixture and incubated overnight at 4°C. The beads were then washed four times in washing buffer (TBS plus 1% Triton X-100) and once with TBS before separation by magnet. Pelleted beads were resuspended in 20 μl of loading buffer (150 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], SDS, 0.3% bromophenol blue, 30% glycerol) and heated to 100°C for 5 min. Samples were then run on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature and blotted. PrP and GABAA α-5 were detected, respectively, with mouse Fab D13 and rabbit anti-GABAA α-5 (Millipore) at 1 μg/ml. After five washes in TBST, blotted PrP protein was detected by incubation for 30 min at room temperature with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (Pierce) diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer. Membranes were then washed five times in TBST and developed with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent onto film.

Neurotransmitter receptor Western blotting.

For detection of GABAA R, glutamate R, and NMDA R, brain tissue was placed in 2-ml polypropylene screw cap tubes (Biospec Products Inc.) filled up to 25% with sterilized glass beads (1.0-mm-diameter beads; Biospec Products Inc.) containing 1 ml sterile 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) with 1% NP-40, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and PIC (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Tubes were placed into the Mini Beadbeater 8 and homogenized for 1 min, and then 500-μl portions of homogenates were transferred to sterile 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 × g to remove debris. Fifteen micrograms of sample was added to reducing sample buffer and processed for Western blot analysis. Samples were run on SDS-polyacrylamide gels; gels were blotted onto PVDF membranes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% powdered skim milk in sterile water. Anti-GABAA R β antibody, anti-GABAA R α1 antibody, anti-GABAA R α2 antibody, anti-NMDA R 2A antibody, anti-NMDA R 2B antibody, anti-glutamate R 1 antibody, or anti-glutamate R 2/3 antibody (all antibodies from Millipore) or anti-β actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as an internal control was added individually at a 1/1,000 dilution to membranes and incubated overnight at 4°C. Membranes were rinsed with buffer and stained with appropriate secondary HRP-conjugated antiserum diluted 1/20,000. Bands were detected using either the Pico or Phemto chemiluminescent detection kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) (35). To evaluate the contribution of inhibitory regulation, bicuculline methiodide (Sigma) was injected directly into the lateral ventricle of GPI−/− PrP tg mice.

Statistics.

Results were derived from calculations performed on all variables and were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). An analysis of variance was performed, followed by a Fisher probable least-squared difference test. A P value of <0.05 was judged statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Immunochemical and Western blot analysis of GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie.

The disassociation of PrPres formation and deposition from overt cerebellar, extrapyramidal, and pyramidal CNS disease manifestations in the GPI-anchorless tg mouse provides a window of opportunity for analyzing the results of PrPres deposition alone (9, 35) over time. Figure 1A and B show both PrPres (red: Fig. 1A) and amyloid (green, Thioflavin S staining; Fig. 1B) in the brain of a GPI−/− PrP tg mouse 400 days after RML murine scrapie infection, and Fig. 1C shows the relative lack of apoptosis during the same period. At this time and over the next 200 to 300 days, these GPI−/− PrP tg mice were alive and had no clinical signs of the cerebellar, extraparymidal, or pyramidal disorder typically associated with scrapie infection (100% of 46 mice tested). In contrast, all mice with an anchored PrP and inoculated with the same dose of RML scrapie had clinically severe neurodegenerative disease within 150 days and died by day 160th ± 6 after infection (mean ± one standard deviation; 24 of 24 mice).

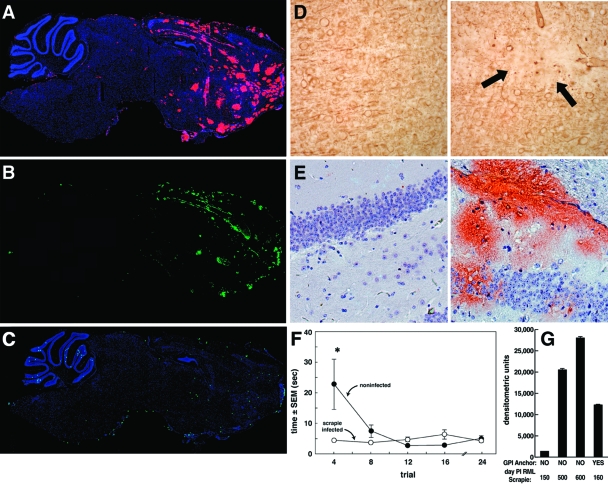

FIG. 1.

Immunochemical and Western blot analysis of scrapie-infected brains. (A, B, and C) Sagittal sections from GPI−/− PrP tg mice obtained 400 days following intracerebral infection with RML murine scrapie. (A) PrPres deposits (pink) reactive with monoclonal antibody D13. (B) Amyloid deposits (green) seen with Thioflavin S. (C) Results from terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling, revealing only a low numbers of cells undergoing apoptosis. (D) Left, uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg mouse; right, loss of dendrites using MAP-2 antibody (arrows). (E) Hippocampal sections from GPI−/− PrP tg mice not infected (left) or infected for 350 days with scrapie (right) and stained with D13 monoclonal antibody to show PrPres deposits. Results are similar to those illustrated in panels A to D for four other age- and sex-matched infected mice. GPI−/− PrP tg mice inoculated with PBS and normal C57BL/6 mice (four per group) had no PrPres or amyloid deposits according to the same immunohistochemical procedures but showed some neuronal apoptosis. (F) Freezing-like behavior and mean time ± SEM that uninfected mice and scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice used to run for protective cover. At least 10 mice were used in each group. *, P < 0.001. (G) Western blot analysis with quantitation by densitometry to assess the amounts of PrPres deposits at various times following scrapie infection of GPI−/− PrP tg mice (NO) compared to GPI-anchored C57BL/6 mice infected with scrapie and sacrificed when moribund (YES). GPI−/− PrP scrapie-infected tg mice were clinically free of pyramidal, extrapyramidal, or cerebellar signs at all times shown. Data are means ± SEMs (for at least five mice per group at each time point).

Histopathologic analysis of brains from clinically healthy GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie showed gliosis and minimal spongiosis. Immunochemical study using MAP-2 antibodies revealed a few focal areas of modest neuronal dendritic cell loss (Fig. 1D, right; compare to negative control left panel) throughout the entorhinal and cerebral cortex and the hippocampus. Considerable PrPres deposition also occurred in the hippocampus (Fig. 1E). CNS deposits of PrPres increased over time, as depicted in Fig. 1G, and by 500 days after scrapie inoculation far exceeded the amount of PrPres deposition found in scrapie-infected mice with anchored PrP that were sacrificed 160 days later or when moribund. When placed in an open field, the infected mice immediately began searching for cover (10 of 10 mice; day 350 postinfection) instead of initially standing still, i.e., freezing, as uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg mice did (Fig. 1F). The lack of a freezing behavior has been reported in sheep and in deer infected with scrapie (38), presumably reflecting a malfunction of the prefrontal cortex (25).

GPI−/− tg mice infected with scrapie have marked deficits in learning, memory, and hippocampal electrophysiology.

We then performed a series of cognitive training and electrophysiologic tests. GPI−/− PrP tg littermates were divided into two sex- and age-matched groups: one infected with scrapie and the other treated with vehicle. Both groups showed visual and auditory acuity. We then examined all mice 193 and 400 days after inoculation to chart their learning and behavior in a cued version of the Barnes circular maze described in Materials and Methods (3, 13) (Fig. 2A). The test objective was how well mice learned to navigate for escape by seeking a visual clue. Noise (90 dB) and/or bright ambient light (100 W) was used as a stimulus. Visual clues located directly behind a hole leading to the escape tunnel were varied randomly from session to session. We then assessed the latency time to begin exploration and to find the escape tunnel, the number of errors made while seeking the escape tunnel, and the search strategy used. Strategies scored were classified as random to serial (strategy of searching every hole in a clockwise or counterclockwise manner) or cued (locating a visual cue for direct access to the escape tunnel) (Fig. 3). As cartooned in Fig. 2A (right) and with data provided in Fig. 3, after over 42 trials consisting of two trials per day with each trial separated by 20 min performed on consecutive days, all 10 scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice continued random exploration and failed to learn the cued visual signals. In contrast, all 10 uninfected GPI−/− PrP mice successfully used serial learning to seek escape after only 7 trials, and within 12 trials all used the cued strategy to locate the escape tunnel (Fig. 2A [left] and 3). Thus, in addition to loss of a freezing-like response (Fig. 1F), GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie, despite the absence of overt signs of neurodegenerative disease, displayed profound deficits in cognitive learning by 400 days postinoculation although not at 193 days postinfection.

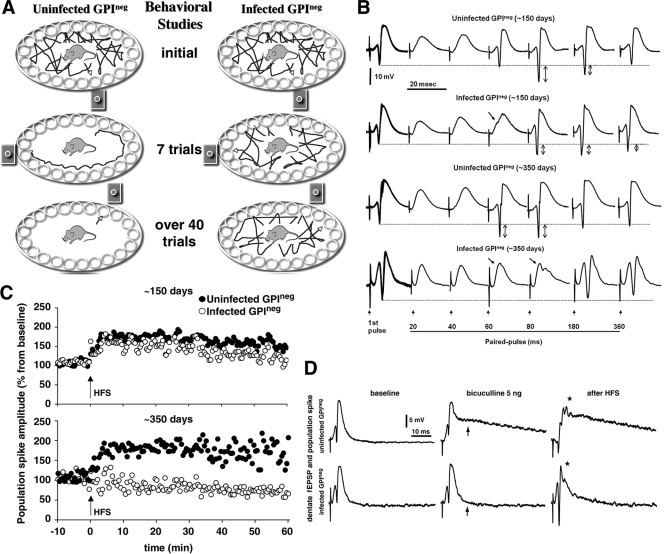

FIG. 2.

GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie have deficits in memory and hippocampal electrophysiology. (A) All 10 infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice (right) continued random exploration and failed to learn cued visual signals to escape. In contrast, all 10 uninfected control mice (left) used serial learning to seek the escape hole within 7 trials, and by the 12th trial all 10 mice used cued strategy to locate the escape tunnel. (B) Interstimulus interval studies show an increase in PPI for the infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice over that in controls. At 150 days after scrapie infection, GPI−/− PrP tg mice (one representative sample of five mice studied) show inhibition in the PP extending up to 60 ms (arrows), and by 350 days that inhibition lasted for 80 ms (arrows) with a total absence of PPF (up-and-down arrows) extended from baseline (dashed line). A recording of hippocampal DG neurons after perforant path stimulation is shown. (C) Absence of LTP in the infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice at 350 days after scrapie infection (bottom) despite its presence at 150 days after infection (top). (D) Increased excitability induced by bicuculline given in the lateral ventricles of uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg mice but a negligible response in the GPI−/− PrP infected tg mice so treated (see arrows with bicuculline-treated mice). HFS of the perforant path elicited multiple spikes followed by long-duration depolarization (∼140 ms) in all GPI−/− PrP uninfected controls. *, P < 0.001. GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie displayed enhanced population spiking followed by a short duration of depolarization (∼20 ms).

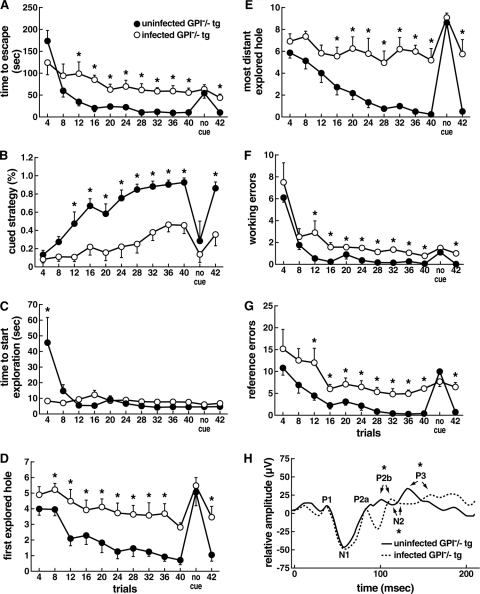

FIG. 3.

Behavioral and learning comparison of uninfected and scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice in attempts to escape the Barnes maze. The maze, as depicted in Fig. 2A, was used to test the acquisition of cued learning. Scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice failed to learn escape behavior in over 42 trials. Trials 1 to 40 are shown in blocks of four and blocks of two that include no use of a cue for trials 41 and 42. (A) Scrapie-infected mice take longer than uninfected mice to find the escape tunnel. (B) Scrapie-infected mice rarely or never use cued strategy or improve in the skill. (C) Infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice show a reduction in latency to start exploration only on the first four trials (first block), which is the time interval between removal of the cylindrical chamber and when the animal moves from the center of the platform. (D and E) The cued search strategy is the most efficient way to find the escape tunnel, whereby the animal uses location of the cue to find the target hole. The criteria to determine the use of the cue strategy require that the first hole explored is located no more than two holes away from the escape tunnel (cue field). GPI−/− PrP-infected tg mice showed a significant deficit in using cues, since the first hole they explored was outside of the cued field (D) and the other holes examined often lay far from the escape tunnel (E). (F and G) Quantification of reference error is defined as holes explored that did not have a cue or lead to the escape tunnel (F); working errors are defined as explored holes that were previously visited (G). The values shown indicate the extent of the deficit in GPI−/− PrP infected tg mice in the ability to associate cues with escape (*, P < 0.05 by paired t test). Dependency on a cue to find the escape tunnel was tested in two additional trials (no cue) between trials 40 and 41; performances were similar for both groups in all parameters. (H) Visual evoked response after flash delivery (100 flashes of 0.1-ms duration, 16 intensity, and 1/s frequency) in order to test the visual response to light stimulation. All scrapie-infected and uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg mice responded to light stimulation, although infected mice showed a slight delay in P2a, N2, and P3 waves. Error bars indicate SEMs.

Next we measured the electrophysiologic transmission of evoked stimuli from the entorhinal cortex to the DG (Fig. 2B and C) and from the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus to medial prefrontal cortex (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). From microelectrodes stereotaxically oriented into the granular layer of the DG, population spikes were recorded as negative potential superimposed on the positive-going field excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP)/inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) complex. The waveform consisted of relatively fast negative-going population spikes superimposed on the field EPSP/IPSP complex. An input/output curve was determined, and the intensity of stimulation used to generate PP response and LTP was set at the half-maximum level. PP curves were generated by testing various interstimulus intervals (0.010 to 1.0 s) of orthodromic paired stimuli. Representative samples are shown in Fig. 2B. At 150 days postinfection, uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg controls displayed a period of PP inhibition (PPI) during the initial 20 and 40 ms and a period of PP facilitation (PPF) from 60- to 80-ms interstimulus intervals, which in 80% of the mice extended up to 180 ms. In contrast, whereas the infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice displayed similar inhibition at 20 and 40 ms, inhibition extended up to 60 ms (n = 6, where the population spike amplitude was 24.3 ± 21.1 for scrapie-infected mice and 101.4 ± 12.39 for control mice [P = 0.008]).

When other matched groups of GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie or not were tested at 350 days postinfection, the PPI increased dramatically in the infected mice. The uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg controls displayed PPI during the initial 20 and 40 ms and PPF at 60-, 80-, 180-, and 360-ms interstimulus intervals. In contrast, their infected counterparts showed an extended inhibition at 60 ms (n = 5, where the population spike amplitude was 16.8 ± 15.8 for scrapie-infected mice and 121.3 ± 18.6 for control mice [P = 0.002]) and 80 ms (41.4 ± 17.89 for scrapie-infected mice and 139.4 ± 12.14 for control mice [P = 0.001]). In addition PPF was absent at 180 ms (89.34 ± 7.6 for scrapie-infected mice and 117.4 ± 4.89 for control mice [P = 0.01]) and 360 ms (99.35 ± 10.2 for scrapie-infected mice and 101.5 ± 17.4 for control mice [P = 0.89]). At 150 days after scrapie infection, GPI−/− PrP tg mice had inhibited the PP response extending up to 60 ms (Fig. 2B). By 350 days, that inhibition lengthened to 80 ms, with an absence of PPF extended from the baseline to the peak amplitude of the population spike (Fig. 2B). Thus, defects were characterized by extended inhibition at longer intervals in scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice in the absence of facilitation. Failure to achieve adequate levels of potentiation in the medial prefrontal cortex after extinction was reported to be associated with a deterioration of the fear response (18). Our corresponding findings for GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie highlighted defects in synaptic efficacy in the medial prefrontal cortex possibly causing the loss of the freezing response (Fig. 1F).

The hippocampus is a region of the brain associated with learning and memory (20, 23). LTP that strengthens synaptic efficacy in the hippocampus has been considered a correlate of memory formation (19, 23). Owing to our finding of defective cognitive learning in scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice (Fig. 2A) and heavy deposits of PrPres in the hippocampus (Fig. 1E), we compared, using published techniques (13), LTP in the hippocampi of GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with scrapie or not at 150 and 350 days postinjection following HFS (three trains consisting of five pulses at 400 Hz) in the perforant path. As recorded in Fig. 2C, at 150 days after scrapie inoculation and after HFS, infected mice had somewhat enhanced population spike amplitude (52% ± 3% from baseline) in the DG but less than that in uninfected controls (n = 6 per group; each dot represents a response elicited every 30 s) (P > 0.05). However, the differences in these values were dramatic at 350 days postinfection, when the infected mice had no further increase in change of population spike amplitude after HFS, whereas the control group underwent the expected increase of 1.5- to 2-fold (n = 5 per group; P < 0.001). These results were confirmed in an additional experiment and duplicated when outcomes of stimulation from the medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus were recorded in the mid-prefrontal cortex (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Abnormalities of synaptic transmission could result from deficits of excitatory pathways (glutamatergic/NMDA) or increased inhibitory inputs of the GABAergic pathway (4, 5, 12, 37). To evaluate the contribution of inhibitory regulation, we administered bicuculline methiodide, a competitive antagonist of the GABA receptor (5), directly into the lateral ventricles of GPI−/− PrP tg mice with scrapie infection for 350 days. Population spikes and EPSP/IPSP from the DGs of these mice were then compared to those of uninfected matched controls. Extracellular electrophysiological analyses revealed a greater susceptibility to bicuculline at increasing concentrations (5, 10, 20, and 50 ng/1 μl of artificial spinal fluid vehicle) in uninfected mice than in scrapie-infected mice. As shown in Fig. 2D, bicuculline given at 5 ng/μl induced a dramatic difference in excitability. Under this condition, a perforant path stimulation-induced enhancement of population spiking had a differential effect on the short-latency response, as well as long-latency, long-duration discharge (depolarization) in the uninfected controls, but little or no such increase in the GPI−/− PrP tg infected mice (Fig. 2D). HFS of the perforant path elicited multiple spikes followed by long-duration depolarization (∼150 ms) in all GPI−/− uninfected controls (Fig. 2D) (n = 5). Under the same conditions, GPI−/− PrP infected mice had enhanced population spiking alone followed by short-duration depolarization (∼20 ms; P = 0.001). Thus, the excitation-inhibition balance was significantly disrupted in the GPI−/− PrP tg mice at 350 days after scrapie infection. Further, 100% of uninfected controls (5/5) had tonic-clonic seizures that correlated with electrical depolarization at a higher dosage of 10 ng/μl. In contrast, infusion of 25 ng/μl of bicuculline into scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice did not cause tonic-clonic seizures in four of five mice (80%). It is likely that the absence of 1 ng latency depolarization potential found in scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice treated with bicuculline indicated a persistent inhibition that blocked excitatory feedback onto the granule cells.

Association of PrP with the GABAergic pathway.

Lastly, the association between GABAA Rs and PrPsen or PrPres was explored by using coimmunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis as well as dual immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal antibodies to NMDA, glutamate, and GABAA Rs and PrP to compare responses from uninfected and scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice. Uninfected tg mice inoculated intracerebrally with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and sacrificed at various times later failed to show either PrPres or any upregulation of NMDA, glutamate, or GABAA Rs compared to uninoculated GPI−/− PrP tg mice. Similarly, when such tg mice were inoculated with scrapie and sacrificed at the corresponding times, no upregulation of either NMDA or glutamate R followed. In contrast, in such scrapie-infected mice GABAA Rs were upregulated, as illustrated in Fig. 4A and B. Western blot analysis revealed no differences between these infected mice and infection-free mice as to excitatory pathway (NMDA or glutamate) components (Fig. 4A). However, differences between the two groups were marked with respect to the inhibitory GABA pathway GABAA R subunits, specifically with GABAA R α5 (four of five mice, two of three mice shown) and GABAA R β (six of six mice, three of three mice shown) at 400 and 600 days after scrapie infection. The differential expression of GABAA β and α subunits (in our studies β1, 2, and 3 and α1, α2, and α5) was confirmed by testing with monoclonal antibodies. All three β subunits collectively were upregulated, as was α5 but not α1 or α2, during scrapie infection (Fig. 4B). Previously, GABAA Rs have been reported to display an extensive heterogeneity based on differential assembly of subunits into distinct receptor complexes (15). This extraordinary heterogeneity in the distribution of GABA R subunits is believed to provide flexibility in signal transduction (15). The enhanced GABAA R β subunit expression was also observed by immunohistochemistry and increased over time (days 300 to 700) after scrapie infection (Fig. 4C). In parallel, PrPres deposition grew over time. These events were observed in three mice sacrificed at each time point shown and recurred in consecutive sections from a single mouse at each time recorded in Fig. 4C. Coimmunoprecipitation was then performed to determine whether PrP was directly connected with increased expression of the GABAA R (Fig. 4D and E). Immunoprecipitation of brain material from uninfected tg mice with antibody against PrP (D13) followed by probing for selected subunits of the GABAA R clearly demonstrated that PrPsen is associated with GABAA R β (Fig. 4D, lane 2). This association of GABAA R β with PrP was markedly greater in brain tissue from infected tg mice tested at 400 days postinfection (P ≤ 0.001) than in that from uninfected tg mice (Fig. 4D, lane 3). No such association was detected for receptors for NMDA or glutamate (data not shown). Similarly, when monoclonal antibodies against GABAA R β or GABAA R α5 were first used to precipitate brain material from GPI−/− PrP tg scrapie-infected mice 400 to 600 days after inoculation and the immunoprecipitate was probed against PrP (D13 antibody), PrPres was found.

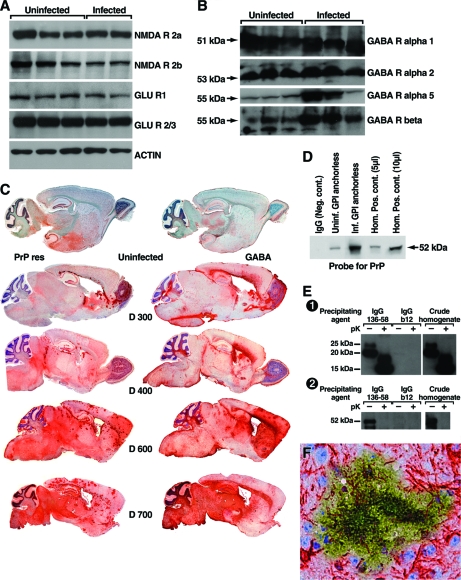

FIG. 4.

Association of PrP with the GABAergic pathway. (A and B) Results from Western blotting using a series of monoclonal antibodies to detect NMDA or glutamate R (A) or GABA R (B) from individual uninfected or RML scrapie-infected 400- to 450-day-old GPI−/− PrP tg mice. The expression of the NMDA or glutamate R was similar in the uninfected or scrapie-infected mice shown and in four additional age- and sex-matched uninfected or scrapie-infected mice (not shown) studied at 600 to 700 days postinfection. In contrast, a marked increase in expression of GABAA R α5 and GABAA R β subunits but not of GABAA R α1 or α2 occurred at both time points (total of four to six mice per time period). (C) Paired sagittal brain sections taken from one uninfected mouse at 450 days old and stained for PrPres (upper section on the left) or for GABAA R β (upper section on the right) expression. No PrPres was detected by Western blotting, indicating background staining for PrPsen. Tissues were fixed and processed for antigen retrieval as outlined in Materials and Methods. This quenches excessive GABA signal and allows immunochemical comparison with PrPres. The increasing deposition of PrPres (left sections) and increasing expression of GABAA R β (right sections) are shown in sections taken 300, 400, 600, and 700 days after scrapie infection from representative GPI−/− PrP tg mice. Paired 5-μm sections separated by not more than 10 μm were taken at the indicated times from each infected mouse. Results were similar for three additional infected mice sacrificed at each of the times shown as well as for four mice sacrificed at 500 days postinfection. In contrast, two uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg mice inoculated with PBS and sacrificed 500 and 700 days later failed to show either PrPres or upregulated GABAA R by either immunohistochemical testing or Western blot analysis. (D) Association of PrP and GABAA R β in uninfected and infected tg mice (day 400) is shown by immunoprecipitation with anti-PrP monoclonal antibody (D13) followed by immunoblotting for the presence of GABAA R β. Interaction between PrPsen and GABA R β is detectable in the brains of uninfected tg mice (lane 2). Brains from infected tg mice contain significantly more (P < 0.001) GABAA R β associated with PrP (lane 3). Ig isotype matched controls are shown in lane 1. Whole-brain homogenates (5 and 10 μl; lanes 4 and 5, respectively) served as a positive control for the presence of GABAA R β. (E) Specific coimmunoprecipitation of PrPres with GABAA R α5 from scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice. The PrPres-specific antibody made by grafting PrP aa 136 to 158 onto the HIV monoclonal antibody b12 (first two lanes) precipitated GABAA R, but the control HIV b12 antibody missing the PrPres graft (lanes 3 and 4) did not. Whole-brain homogenates from scrapie-infected GPI−/− PrP tg mice were treated (+) or not (−) with proteinase K. Antibodies were then precipitated with polyclonal rabbit anti-human IgG F(ab′)2 linked to paramagnetic beads. Precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of PrP (panel 1) and GABAA R α-5 (panel 2). Brain homogenate (lanes 5 and 6) was included as a positive control for the presence of PrP and GABAA R α-5. (F) Localization of upregulated GABAA R β and PrPres deposits by immunohistochemistry. Overlaid (60×) adjacent brain sections (within 5 μm) stained for the presence of GABAA R (β; red) or PrPres (green). Only areas directly adjacent to PrPres deposits displayed increased GABAA R staining.

For the results depicted in Fig. 4E, we used a reagent specific for PrPres to document and confirm coimmunoprecipitation with GABAA R. A PrPres-specific motif of aa 136 to 158 was grafted onto a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody molecule (b12) as reported previously (26, 33). Panel 1 of Fig. 4E shows that this PrPres-specific motif-engrafted antibody precipitated PrPres from the brain of a GPI−/− PrP tg mouse infected with RML scrapie but that the b12 antibody alone did not. Panel 2 of Fig. 4E shows that antibody against GABAA R α5 coimmunoprecipitated with PrPres. In contrast, the HIV antibody molecule (b12) without the grafted PrPres-specific motif of aa 136 to 158 failed to precipitate the GABAA R.

Dual immunochemical staining using specific monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 4F) shows GABAA R β (red) interlaced with PrPres deposit (yellow green). This interlacing of GABAA R with PrPres was a common occurrence throughout the brain by 400 days after scrapie infection.

Earlier, electrophysiologic analysis of hippocampal brain slices from PrP knockout mice identified a reduction of GABAA R-mediated synaptic transmission and attenuation of LTP in vitro (10, 11, 24). Our results with GPI−/− PrP tg scrapie-infected mice in vivo complement these studies by revealing upregulation of GABAA R associated with enhanced deposition of PrPres and the likely association of PrPsen with GABAA R. Further, our findings support earlier studies by Lu et al. (22) and Bouzamondo-Bernstein et al. (6), who noted an increase in the total number of GABA-immunopositive neurons in brains of hamsters infected with scrapie. Additionally, GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with RML scrapie did not develop the severe and selective loss of GABAergic neurons found by Guentchev et al. (17) in GPI-anchored PrP mice injected with either RML scrapie or CJD Fujisaki strain. Immunochemical studies of brains from CJD patients have produced varied results dependent on the area of the CNS sampled (17).

Our study of GPI−/− PrP tg mice infected with RML murine scrapie documents that PrPres deposition within the frontal cortex and hippocampus despite the animals' lack of obvious neurodegenerative disease coincides with a disruption of learning and memory as determined by cued Barnes testing and defects in LTP. These dysfunctions in learning and memory do not correlate with neuronal death, dropout, or apoptosis. Instead, the faulty learning and memory are likely associated with increased inhibition via the GABAergic pathway, according to results stemming from the addition of bicuculline during LTP studies in vivo. Supporting that conclusion are outcomes from direct immunochemical analysis of neurotransmitters and neurotransmitter profiles within brains of scrapie-infected and uninfected GPI−/− PrP tg mice. Finding PrPres deposition and upregulation of GABAA R β and α5 subunits in the same loci of the brain suggests a possible direct interaction between these molecules. The association of PrPsen and GABAA R β subunits, although of a low intensity, suggests that the normal PrP molecule may function in vivo with the GABAergic pathway, which becomes overexcited during PrPres deposition. Presumably the result would be a decreased capacity for learning and memory in the scrapie-infected host. The previous failure of Kannenberg and associates (21) to find a physical association between cellular PrP and GABAA R likely reflects the sensitivity of the protein purification scheme that they employed. The GABAA R is a ligand-gated Cl− ion channel. Our attempts to evaluate Cl− ion channels using patch clamps on hippocampal slices from adult GPI−/− PrP tg mice that had PrPres deposits failed technically because of the age of the specimen used. Nevertheless, our results documented here indicate the worthiness of evaluating the Cl− ion channel and possible pharmacologic applications to control GABA or the Cl− ion channel in humans with prion disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This is publication no. 18827 from the Department of Immunology and Microbial Science, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA.

This research was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AG004342 and NIH training grants NS041219 (to M.J.T.) and AI007354 (to J.B.T.).

We thank Floyd Bloom, Iustin Tabarean, and Tamas Bartfai of TSRI and Bruce Chesebro of NIH, Rocky Mountain Laboratory, for helpful discussions and Iustin Tabarean for patch clamp studies. The GPI−/− PrP tg mice were generated in collaboration with Bruce Chesebro.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 July 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailly, Y., A. M. Haeberle, F. Blanquet-Grossard, S. Chasserot-Golaz, N. Grant, T. Schulze, G. Bombarde, J. Grassi, J. Y. Cesbron, and C. Lemaire-Vieille. 2004. Prion protein (PrPc) immunocytochemistry and expression of the green fluorescent protein reporter gene under control of the bovine PrP gene promoter in the mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 473244-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barmada, S., P. Piccardo, K. Yamaguchi, B. Ghetti, and D. A. Harris. 2004. GFP-tagged prion protein is correctly localized and functionally active in the brains of transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 16527-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes, C. A. 1979. Memory deficits associated with senescence: a neurophysiological and behavioral study in the rat. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 9374-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleich, S., K. Romer, J. Wiltfang, and J. Kornhuber. 2003. Glutamate and the glutamate receptor system: a target for drug action. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 18S33-S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloom, F. 2006. Neurotransmission and the central nervous system, p. 317-339. In L. Burton (ed.), Goodman and Gilman: the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. McGraw Hill, New York, NY.

- 6.Bouzamondo-Bernstein, E., S. D. Hopkins, P. Spilman, J. Uyehara-Lock, C. Deering, J. Safar, S. B. Prusiner, H. J. Ralston, and S. J. DeArmond. 2004. The neurodegeneration sequence in prion diseases: evidence from functional, morphological and ultrastructural studies of the GABAergic system. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 63882-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton, D. R., J. Pyati, R. Koduri, S. J. Sharp, G. B. Thornton, P. W. Parren, L. S. Sawyer, R. M. Hendry, N. Dunlop, and P. L. Nara. 1994. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science 2661024-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chesebro, B. 1999. Prion protein and the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy diseases. Neuron 24503-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesebro, B., M. J. Trifilo, R. Race, K. Meade-White, C. Teng, R. LaCasse, L. Raymond, C. Favara, G. Baron, S. A. Priola, B. Caughey, E. Masliah, and M. Oldstone. 2005. Anchorless prion protein results in infectious amyloid disease without clinical scrapie. Science 3081435-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colling, S. B., J. Collinge, and J. G. Jefferys. 1996. Hippocampal slices from prion protein null mice: disrupted Ca(2+)-activated K+ currents. Neurosci. Lett. 20949-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collinge, J., M. A. Whittington, K. C. Sidle, C. J. Smith, M. S. Palmer, A. R. Clarke, and J. G. Jefferys. 1994. Prion protein is necessary for normal synaptic function. Nature 370295-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conn, P. J. 2003. Physiological roles and therapeutic potential of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 100312-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Criado, J. R., M. Sanchez-Alavez, B. Conti, J. L. Giacchino, D. N. Wills, S. J. Henriksen, R. Race, J. C. Manson, B. Chesebro, and M. B. Oldstone. 2005. Mice devoid of prion protein have cognitive deficits that are rescued by reconstitution of PrP in neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 19255-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford, M. J., L. J. Burton, H. Li, C. H. Graham, Y. Frobert, J. Grassi, S. M. Hall, and R. J. Morris. 2002. A marked disparity between the expression of prion protein and its message by neurones of the CNS. Neuroscience 111533-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritschy, J. M., and H. Mohler. 1995. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J. Comp. Neurol. 359154-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giacchino, J. L., J. R. Criado, D. Games, and S. J. Henriksen. 2000. In vivo synaptic transmission in young and aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Brain Res. 876185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guentchev, M., M. H. Groschup, R. Kordek, P. P. Liberski, and H. Budka. 1998. Severe, early and selective loss of a subpopulation of GABAergic inhibitory neurons in experimental transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Brain Pathol. 8615-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herry, C., and R. Garcia. 2002. Prefrontal cortex long-term potentiation, but not long-term depression, is associated with the maintenance of extinction of learned fear in mice. J. Neurosci. 22577-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeffery, K. J. 1997. LTP and spatial learning—where to next? Hippocampus 795-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandel, E. R. 2004. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialog between genes and synapses. Biosci. Rep. 24475-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannenberg, K., M. H. Groschup, and E. Sigel. 1995. Cellular prion protein and GABAA receptors: no physical association? Neuroreport 777-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu, P., J. A. Sturman, and D. C. Bolton. 1995. Altered GABA distribution in hamster brain is an early molecular consequence of infection by scrapie prions. Brain Res. 681235-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynch, M. A. 2004. Long-term potentiation and memory. Physiol. Rev. 8487-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallucci, G. R., S. Ratte, E. A. Asante, J. Linehan, I. Gowland, J. G. Jefferys, and J. Collinge. 2002. Post-natal knockout of prion protein alters hippocampal CA1 properties, but does not result in neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 21202-210. (Erratum, 21:1240.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milad, M. R., and G. J. Quirk. 2002. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature 42070-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moroncini, G., N. Kanu, L. Solforosi, G. Abalos, G. C. Telling, M. Head, J. Ironside, J. P. Brockes, D. R. Burton, and R. A. Williamson. 2004. Motif-grafted antibodies containing the replicative interface of cellular PrP are specific for PrPSc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10110404-10409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishida, N., S. Katamine, K. Shigematsu, A. Nakatani, N. Sakamoto, S. Hasegawa, R. Nakaoke, R. Atarashi, Y. Kataoka, and T. Miyamoto. 1997. Prion protein is necessary for latent learning and long-term memory retention. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 17537-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paxinos, G., and K. B. J. Franklin. 1997. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 29.Prusiner, S. B. 1999. Prion biology and disease. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Prusiner, S. B. 2001. Prions, p. 3063-3087. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 31.Roesler, R., R. Walz, J. Quevedo, F. de-Paris, S. M. Zanata, E. Graner, I. Izquierdo, V. R. Martins, and R. R. Brentani. 1999. Normal inhibitory avoidance learning and anxiety, but increased locomotor activity in mice devoid of PrP(C). Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 71349-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Alavez, M., B. Conti, G. Moroncini, and J. R. Criado. 2007. Contributions of neuronal prion protein on sleep recovery and stress response following sleep deprivation. Brain Res. 115871-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solforosi, L., A. Bellon, M. Schaller, J. T. Cruite, G. C. Abalos, and R. A. Williamson. 2007. Toward molecular dissection of PrPC-PrPSc interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2827456-7471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solforosi, L., J. R. Criado, D. B. McGavern, S. Wirz, M. Sanchez-Alavez, S. Sugama, L. A. DeGiorgio, B. T. Volpe, E. Wiseman, G. Abalos, E. Masliah, D. Gilden, M. B. Oldstone, B. Conti, and R. A. Williamson. 2004. Cross-linking cellular prion protein triggers neuronal apoptosis in vivo. Science 3031514-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trifilo, M. J., T. Yajima, Y. Gu, N. Dalton, K. L. Peterson, R. E. Race, K. Meade-White, J. L. Portis, E. Masliah, K. U. Knowlton, B. Chesebro, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 2006. Prion-induced amyloid heart disease with high blood infectivity in transgenic mice. Science 31394-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valenti, P., A. Cozzio, N. Nishida, D. P. Wolfer, S. Sakaguchi, and H. P. Lipp. 2001. Similar target, different effects: late-onset ataxia and spatial learning in prion protein-deficient mouse lines. Neurogenetics 3173-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiting, P. J. 2003. The GABAA receptor gene family: new opportunities for drug development. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 6648-657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams, E. S., and S. Young. 1992. Spongiform encephalopathies of Cervidae. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epizoot. 11551-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.