Abstract

The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) major immediate-early enhancer has been postulated to play a pivotal role in the control of latency and reactivation. However, the absence of an animal model has obstructed a direct test of this hypothesis. Here we report on the establishment of an in vivo, experimentally tractable system for quantitatively investigating physiological functions of the HCMV enhancer. Using a neonate BALB/c mouse model, we show that a chimeric murine CMV under the control of the HCMV enhancer is competent in vivo, replicating in key organs of mice with acute CMV infection and exhibiting latency/reactivation features comparable for the most part to those of the parental and revertant viruses.

Reactivation of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in an immunocompromised host frequently leads to a variety of severe complications, such as pneumonia, hepatitis, and retinitis (30). The HCMV major immediate-early promoter (MIEP) has been regarded as a key genetic element in determining the commencement of lytic infection and the switch from latency to reactivation (17, 35, 36). The MIEP steers the extent and patterns of expression of the MIE genes, which encode multifunctional proteins required for the productive replication cycle (25, 28). The enhancer region of the MIEP is controlled by a complex interplay between host factors and virally encoded proteins (12, 36). Thus, binding sites for multiple signal-regulated cellular factors, such as NF-κB, CREB/ATF, Sp1, AP-1, YY1, Ets, RAR/RXR, and serum response factors, lie in this regulatory region. The importance of the HCMV MIEP enhancer in the context of the infection of cultured cells has been documented (15, 18, 20, 26, 27). However, the lack of an animal model system that sustains significant HCMV replication has prevented the assessment of the role and mechanisms of action of this region during latent infection. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop in vivo models to address this issue.

Infection of mice with murine CMV (MCMV) has proven to be an invaluable model for studying aspects of the biology of CMV infection. The MCMV MIE locus resembles in many ways its HCMV counterpart, and significant information has been drawn from this system concerning MIE gene functions and MIEP regulation (8, 33). In this context, we have described the absolute requirement of the MCMV enhancer for productive infection in its natural host (13). While the primary sequence and architecture of the MCMV and HCMV enhancers are quite different, they share many of the same signal-regulatory control elements (7, 10, 12), conferring both similar and distinct biological properties to them. Accordingly, the first attempts to study HCMV MIEP function in an intact physiological system involved developing murine transgenic models using an HCMV enhancer linked to a reporter gene (3, 4, 23). However, while informative, these models place the enhancer out of its natural environment of the viral genome and most importantly out of the context of an infection. For these reasons, we sought to address HCMV-enhancer-related questions during viral infection in an in vivo setting by generating the first chimeric humanized MCMV (hMCMV) in which the HCMV enhancer precisely replaces the MCMV enhancer (2). We showed that this enhancer swap virus replicated in permissive NIH 3T3 cells with wild-type kinetics. These observations were extended by Grzimek et al. (14), who used an independent hybrid virus (mCMVhMIEPE) in which the complete MCMV promoter was replaced by both the enhancer and the core promoter of HCMV; this recombinant virus showed normal growth in liver but a partial defect in dissemination or replication within other tissues in immunodepleted BALB/c mice. However, these two enhancer swap viruses were generated on the basis of MCMV genomes lacking one or more viral immunomodulatory genes, which thus led to an attenuated phenotype of the resulting viruses in vivo (24, 37). This deficiency made the quantitative study of the acute infection difficult and greatly impeded the possibility of investigating latency and reactivation issues.

In this report, we have sought to establish a robust in vivo model for studying HCMV enhancer functions in the context of an acute and latent infection. For this purpose, we used a new chimeric virus (hMCMV-ES, where ES signifies enhancer swap [5]) engineered from a full-length MCMV-bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) genome (37) through recombination techniques in Escherichia coli (6). In this recombinant virus, sequences from nucleotides −48 to −1191 of the native MCMV enhancer were replaced by the paralogous sequence from nucleotides −52 to −667 of the HCMV enhancer (Fig. 1A, lines 1 and 2). As a control, we generated a revertant genome by restoring the MCMV enhancer in hMCMV-ES (hMCMV-ESrev) (Fig. 1A, line 3), transfected hMCMV- ESrev into NIH 3T3 cells, recovered the corresponding virus, and subjected it to three rounds of plaque purification, and a viral stock was produced. The genomic integrity of the three viruses used in the study was verified by HindIII digestion of the viral DNAs (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Further characterization of the recombinant MCMVs was performed by DNA digestion with additional restriction enzymes, PCR analysis, and sequencing across the MIE region manipulated (data not shown). Finally, viral stocks were tested by PCR for the appropriate excision of the BAC vector sequences (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), as any remaining BAC sequences in the viral genome could interfere with the natural course of the infection in mice.

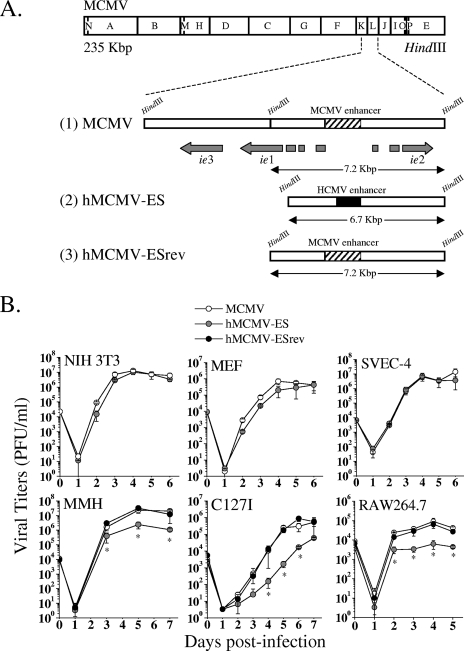

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization and in vitro growth analysis of parental MCMV, hMCMV-ES, and hMCMV-ESrev. (A) Schematic illustrations of the parental MCMV, hMCMV-ES, and hMCMV-ESrev genomes. The top line represents the HindIII map of the parental MCMV genome (11), with the HindIII K and L regions enlarged below to show the MIE locus and with the structure of the MIE transcripts (ie1, ie2, and ie3) indicated. Exons of the ie1-ie3 transcription unit are depicted as gray rectangles. The hatched box represents the MCMV enhancer. Line 1 represents the HindIII fragments K and L from parental MCMV (obtained from the pSM3fr BAC [37]). The hMCMV-ES genome (line 2) was generated by homologous recombination in E. coli (6), with the MCMV pSM3fr BAC taken as the parental genome and with MCMV enhancer sequences from nucleotides −48 to −1191 (relative to the ie1/ie3 MCMV transcription start site) replaced by sequences from nucleotides −52 to −667 (relative to the ie1/ie2 HCMV transcription start site) of the HCMV enhancer (represented by a black box). In the hMCMV-ESrev genome (line 3), the native sequences of the MCMV enhancer were reintroduced in hMCMV-ES by replacement of the HCMV enhancer. Sizes of the natural and new HindIII L DNA fragments for each recombinant genome are indicated. The illustration is not drawn to scale. (B) Growth kinetics of hMCMV-ES and control viruses in different cell types. NIH 3T3 cells, MEF, SVEC-4 cells, MMH cells (treated for 10 days before infection with 2% dimethyl sulfoxide), and C127I cells were infected at an MOI of 0.025 PFU/cell, and RAW264.7 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 PFU/cell, with MCMV, hMCMV-ES, or hMCMV-ESrev. At the designated days p.i., cell supernatants were collected and titrated by standard plaque assays on MEF. Error bars represent standard deviations of the means of results from triplicate cultures. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between hMCMV-ES-, MCMV-, or hMCMV-ESrev-infected samples (P value < 0.05) determined by Student's t test (two-tailed).

We first sought to analyze the growth phenotype of hMCMV-ES in different murine cell types in culture. For this purpose, we infected NIH 3T3 cells, mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEF), an endothelial cell line (SVEC-4), a liver-derived cell line (MMH [1]), an epithelial cell line (C127I), and the macrophagic cell line RAW264.7 with parental MCMV, hMCMV-ES, and hMCMV-ESrev at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI). Figure 1B shows that while no significant growth defects were detected with hMCMV-ES in the first three cell types, a slightly diminished ability (around 1 order of magnitude) to replicate in MMH, C127I, and RAW264.7 cells was exhibited by this recombinant virus. As expected, the revertant virus was identical to the parental virus in growth kinetics in these cell systems. Thus, although the HCMV enhancer was able to complement the native MCMV enhancer in a variety of cultured cells, these data highlight the distinct cell-specific regulation of viral growth by this region.

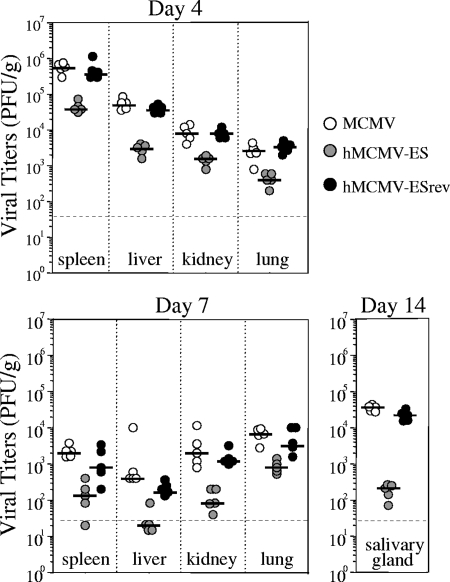

We next proceeded to analyze whether differential sensitivity also exists in the in vivo phenotype of hMCMV-ES in the immunocompetent-BALB/c-mouse model. Groups of 3-week-old mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1 × 106 PFU of hMCMV-ES or the parental or revertant viruses. At 4, 7, and 14 days postinfection (p.i.), viral titers were examined in relevant sites of MCMV replication. As shown in Fig. 2, hMCMV-ES was able to infect and propagate in the spleen, liver, kidneys, lungs, and salivary glands, although it was considerably attenuated (1 to 2 orders of magnitude, depending on the organ) in comparison to the parental and revertant viruses. Similar results were obtained in immunodeficient SCID CB17 mice (data not shown). These data are, overall, consistent with previous observations made with the slightly different hybrid virus mCMVhMIEPE in immunodepleted adult BALB/c mice (14). Altogether, the difference in sensitivity appears to be a general, quantitative attenuation in vivo that was observed for all tissues rather than being specific to a cell/organ system.

FIG. 2.

Growth of hMCMV-ES, parental, and revertant viruses in adult BALB/c mice. Three-week-old BALB/c.ByJ female mice were inoculated i.p. with 1 × 106 PFU per mouse of tissue culture-derived MCMV, hMCMV-ES, or hMCMV-ESrev. Animals were sacrificed at the different times p.i. indicated, selected organs were harvested and sonicated as a 10% (wt/vol) tissue homogenate, and titers were determined by standard plaque assays, including centrifugal enhancement of infectivity (16) on MEF. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection (3 × 101 PFU/g). Horizontal bars indicate the median values. Viral titers in the different organs and times shown were significantly different (P value < 0.05) between groups of animals infected with hMCMV-ES and the parental virus as determined by the Mann-Whitney test (two-tailed).

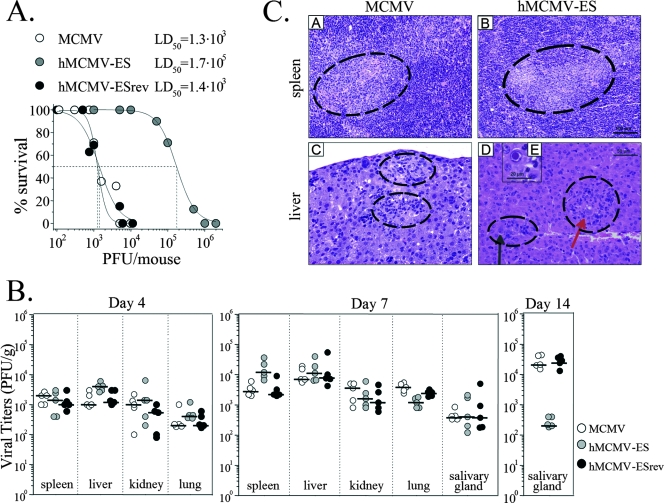

The diminished growth of hMCMV-ES in different tissues during acute infection severely impairs the study of the HCMV enhancer in this system. To overcome this limitation, we initially attempted to infect adult BALB/c mice with higher doses of hMCMV-ES. Although this level of inoculation permitted more-vigorous replication in the different organs tested (data not shown), it generated technical problems associated with the production of highly concentrated viral stocks. In a search of a more sensitive model of infection, we turned to neonatal mice. Work by Reddehase and colleagues (32) has shown that intraperitoneal infection of neonatal BALB/c mice with low doses of MCMV (1 × 102 PFU) leads to significant virus production in different organs and subsequent establishment of latency. Accordingly, we first analyzed the degree of virulence of hMCMV-ES in comparison to that of the parental virus in this system. For this purpose, we challenged groups of 3-day-old BALB/c mice with various doses of hMCMV-ES (ranging from 1 × 103 to 2 × 106 PFU/mouse) or parental and revertant viruses (ranging from 1 × 102 to 1 × 104 PFU/mouse) and evaluated their survival daily for at least a 40-day period. As shown in Fig. 3A, while the estimated 50% lethal dose (LD50) for control viruses was 1.3 × 103 (parental) and 1.4 ×103 (revertant) PFU, the LD50 for hMCMV-ES was 2 orders of magnitude higher, 1.7 × 105 PFU, reflecting the significant decrease in virulence associated with hMCMV-ES.

FIG. 3.

Infection of neonate BALB/c mice with hMCMV-ES. (A) Virulence level of hMCMV-ES in newborn mice. Groups of 7 to 34 3-day-old BALB/c.ByJ female mice were i.p. inoculated with increasing doses of tissue culture-derived hMCMV-ES (ranging from 1 × 103 to 2 × 106 PFU per mouse) or parental or revertant viruses (ranging from 1 × 102 to 1 × 104 PFU per mouse). Animals were monitored daily for survival until at least 40 days postinoculation. Data points were fitted to a sigmoid function available in Origin software, and the LD50 values were estimated from these curves. (B) Growth kinetics of hMCMV-ES in newborn mice. Three-day-old BALB/c.ByJ female mice were i.p. inoculated with tissue culture-derived hMCMV-ES (5 × 104 PFU per mouse), MCMV, or hMCMV-ESrev (5 × 102 PFU per mouse). Mice were sacrificed at different times after infection and specific organs removed. Collected organs were sonicated as a 10% (wt/vol) tissue homogenate, and titers were determined by standard plaque assays, including centrifugal enhancement of infectivity on MEF. All values were among the limits of detection of the assay (5 × 101 PFU). Horizontal bars indicate the median values. The observed differences did not reach statistical difference (P value > 0.05) as determined by the Mann-Whitney test (two-tailed), except for the values for salivary glands at day 14 p.i., with which a significant difference was obtained between the group of animals infected with hMCMV-ES and the group infected with MCMV or hMCMV-ESrev. (C) Histological analysis of livers and spleens from MCMV- and hMCMV-ES-infected newborn mice. Portions of the spleens and livers removed at day 7 p.i. from animals discussed for panel B above were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, processed, and embedded in paraffin by standard procedures. Sections (3 to 4 μm) were cut with a rotary microtome and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for examination. Shown are sections from spleens of MCMV-infected animals (subpanel A) and hMCMV-ES-infected animals (subpanel B), with regions exhibiting mild lymphoid depletion in the white pulp enclosed by dashed lines. These lesions were frequently associated with discrete inflammatory aggregates mostly constituted by macrophagic cells and occasionally accompanied by eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies. (Subpanels C to E) Liver sections of MCMV-infected mice (subpanel C) and hMCMV-ES-infected mice (subpanels D and E), where moderate inflammatory lesions dispersed through the parenchymata can be recognized (enclosed by dashed lines). Scattered necrotic hepatocytes, cytomegalic cells (red arrow in subpanel D), and Cowdry type A intranuclear inclusions bodies (inset subpanel E and black arrow in subpanel D) could be distinguished in these inflammatory foci. The bars represent 100 μm in panels A to B, 50 μm in panels C to D, and 20 μm in panel E.

Based on the LD50 values determined, and in order to establish conditions that allowed a robust hMCMV-ES infection comparable to that of wild-type MCMV, we proceeded to inoculate 3-day-old BALB/c mice with a viral dose corresponding to 0.3 LD50 (5 × 102 PFU/mouse for control viruses and 5 × 104 PFU/mouse for hMCMV-ES). We then evaluated the growth of hMCMV-ES in comparison to that of the control viruses in the major target organs for CMV at different days p.i. Under these conditions, hMCMV-ES grew to levels equivalent to and followed a course similar to those of the parental and revertant viruses in spleen, liver, lungs, kidneys, and salivary glands at days 4 and 7 after infection (Fig. 3B). Reduced viral yields (compared to those from mice infected with the corresponding controls) were found only in the salivary glands of hMCMV-ES-infected animals 14 days after inoculation. Direct inoculation of the chimeric virus in the submaxillar gland did not ameliorate this partially impaired growth (data not shown), thus suggesting a particular defect of hMCMV-ES in replicating in this gland more than an incapacity of the mutant virus to successfully reach it. Therefore, except in the salivary glands, conditions were established in the neonatal murine model that allowed hMCMV-ES to disseminate and replicate in relevant organs involved in acute infection. In agreement with the viral titers obtained, signs of MCMV-associated pathology were observed in the different organs analyzed from hMCMV-ES-infected animals and were more prominent in spleens and livers than in other organs. Figure 3C shows some of the lesions observed in these two organs. While, quantitatively, lesions in the spleens of hMCMV-ES- and MCMV-infected mice were very similar, slightly more frequent and florid lesions were observed in the livers of animals inoculated with the virus with the replaced enhancer.

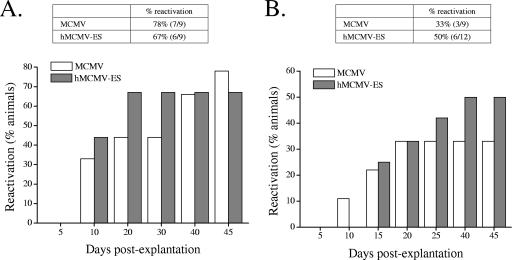

We next examined whether, under these experimental conditions, hMCMV-ES was capable of establishing latency and subsequently reactivating from this state. Groups of 9 to 12 3-day-old mice were infected with 5 × 104 PFU of hMCMV-ES or 5 × 102 PFU of the parental virus. After 4 months, when persistent virus could no longer be detected in salivary gland homogenates, viral reactivation was investigated with splenic and lung explants as described by Jordan and Mar (21) and Presti et al. (31), systems that have proven to be more efficient and reproducible than in vivo reactivation techniques. As shown in Fig. 4, reactivation in spleens was detected in 78% of animals infected with the parental virus and in 67% of animals infected with hMCMV-ES. The frequency of reactivation of hMCMV-ES in the lungs, although lower than in spleens, was also similar to that exhibited by the parental virus (50% and 33% for the mutant and the parental virus, respectively). In addition, in both organs, the reactivation of the two viruses followed roughly similar kinetics. Thus, under the experimental conditions established, the efficiency and dynamics of reactivation of hMCMV-ES in explant cultures were comparable to those of the parental virus.

FIG. 4.

Reactivation of hMCMV-ES virus. Groups of 9 to 12 3-day-old BALB/c.ByJ female mice were i.p. inoculated with tissue culture-propagated hMCMV-ES (5 × 104 PFU per mouse) or the parental virus (5 × 102 PFU per mouse) and maintained for 4 months to establish latency. Animals were sacrificed and their spleens, lungs, and salivary glands harvested. Reactivation was examined from spleens and lungs, which were manually minced and placed with medium in wells of a six-well plate. Cultures were kept (with fresh medium addition when required) for 50 days. Every 5 days, part of the supernatant was transferred to MEF monolayers (a centrifugal enhancement of infectivity step was included) for detection of infectious virus. Graphics show the cumulative frequencies of reactivation events over time from spleen (A) and lung (B) explants. The percentages of reactivation accumulated at day 50 postexplantation are indicated in the corresponding tables, with the number of positive mice versus the number of total animals per group shown in parentheses. The identities of the reactivated viruses (which differ within groups in the sizes of the HCMV and MCMV enhancer regions) were confirmed by PCR analysis using two primers that bind to viral sequences flanking the MCMV enhancer and as template viral DNAs from the indicator MEF cultures when a cytopathic effect was reached (data not shown). In addition, PCR products from a representative sample of each group and organ were cloned and sequenced. Salivary glands were analyzed to ensure the clearance of infectious virus at the time of explantation by sonicating them as a 10% (wt/vol) tissue homogenate and subsequently transferring them to MEF monolayers. Data shown correspond to results from one of two independently performed experiments in which comparable results were obtained. Percentages of reactivation between MCMV and hMCMV-ES were not statistically different, as determined by the chi-square test (two-tailed).

The exchange between enhancers of different CMV species results in hybrid viruses with similar or slightly diminished in vitro replication abilities but significantly altered dissemination capacities and/or host cell tropisms (2, 14, 18, 34). These observations highlight the biological significance of this regulatory region, most likely adapted during coevolution to suit species-specific niches. In order to develop a system that allows the study of the HCMV enhancer in the different settings in vivo, we have used here the hMCMV-ES virus and the neonate mouse model and established conditions of infection that mostly reproduce the extent of viral replication in different organs and parallel latency/reactivation properties of parental MCMV. Until now, the study of particular genetic elements of the HCMV enhancer in the context of the complete viral genome has been restricted to a few tissue culture systems (5, 9, 15, 19, 22, 29). Thus, for the first time, it is possible to ascertain the roles of selective HCMV enhancer binding elements, cellular factors, and signaling pathways operating through this region in an intact physiological system, in the establishment and maintenance of latency, and in the control of the reactivation events in the context of an in vivo infection. Knowledge of the mechanisms governing enhancer function may lead to new strategies for controlling primary and recurrent HCMV infections, with the small-animal model system established here being a valuable tool for their evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Alberto Marco and Gloria Nejar for help with the histopathology analysis. We thank Clara Estévez for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (SAF2005-05633 to A.A.), the Wellcome Trust (to P.G. and A.A.), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 587, A13 to M.M.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 August 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amicone, L., F. M. Spagnoli, G. Späth, S. Giordano, C. Tommasini, S. Bernardini, V. De Luca, C. Della Rocca, M. C. Weiss, P. M. Comoglio, and M. Trípoli. 1997. Transgenic expression in the liver of truncated Met blocks apoptosis and permits immortalization of hepatocytes. EMBO J. 16495-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angulo, A., M. Messerle, U. H. Koszinowski, and P. Ghazal. 1998. Enhancer requirement for murine cytomegalovirus growth and genetic complementation by the human cytomegalovirus enhancer. J. Virol. 728502-8509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baskar, J. F., P. P. Smith, G. S. Climent, S. Hoffman, C. Tucker, D. J. Tenney, A. M. Colberg-Poley, J. A. Nelson, and P. Ghazal. 1996. Developmental analysis of the cytomegalovirus enhancer in transgenic animals. J. Virol. 703215-3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskar, J. F., P. P. Smith, G. Nilaver, R. A. Jupp, S. Hoffmann, N. J. Peffer, D. J. Tenney, A. M. Colberg-Poley, P. Ghazal, and J. A. Nelson. 1996. The enhancer domain of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter determines cell type-specific expression in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 703207-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedict, C. A., A. Angulo, G. Patterson, S. Ha, H. Huang, M. Messerle, C. F. Ware, and P. Ghazal. 2004. Neutrality of the NF-κB-dependent pathway for human and murine cytomegalovirus transcription and replication in vitro. J. Virol. 78741-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borst, E. M., C. Benkartek, and M. Messerle. 2007. Use of bacterial artificial chromosomes in generating targeted mutations in human and mouse cytomegaloviruses, p. 10.32.1-10.32.20. In J. E. Coligan, B. Bierer, D. H. Marguiles, E. M. Sherach, W. Strober, and R. Coico (ed.), Current protocols in immunology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Boshart, M., F. Weber, G. Jahn, K. Dorsch-Hasler, B. Fleckenstein, and W. Schaffner. 1985. A very strong enhancer is located upstream of an immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus. Cell 41521-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busche, A., A. Angulo, P. Kay-Jackson, P. Ghazal, and M. Messerle. 2008. Phenotypes of major immediate-early gene mutants of mouse cytomegalovirus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caposio, P., A. Luganini, G. Hahn, S. Landolfo, and G. Gribaudo. 2007. Activation of the virus-induced IKK/NF-kappaB signalling axis is critical for the replication of human cytomegalovirus in quiescent cells. Cell. Microbiol. 92040-2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorsch-Hasler, K., G. M. Keil, F. Weber, M. Jasin, W. Schaffner, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1985. A long and complex enhancer activates transcription of the gene coding for the highly abundant immediate early mRNA in murine cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 828325-8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebeling, A., G. M. Keil, E. Knust, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1983. Molecular cloning and physical mapping of murine cytomegalovirus DNA. J. Virol. 47421-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghazal, P., and J. A. Nelson. 1993. Transcription factors and viral regulatory proteins as potential mediators of human cytomegalovirus pathogenesis, p. 360-383. In Y. Becker, G. Darai, and E.-S. Huang (ed.), Molecular aspects of human cytomegalovirus diseases. Springer-Verlag Publishers, Heidelberg, Germany.

- 13.Ghazal, P., M. Messerle, K. Osborn, and A. Angulo. 2003. An essential role of the enhancer for murine cytomegalovirus in vivo growth and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 773217-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grzimek, N. K. A., J. Podlech, H.-P. Steffens, R. Holtappels, S. Schmalz, and M. J. Reddehase. 1999. In vivo replication of recombinant murine cytomegalovirus driven by the paralogous major immediate-early promoter-enhancer of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 735043-5055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustems, M., E. Borst, C. A. Benedict, C. Pérez, M. Messerle, P. Ghazal, and A. Angulo. 2006. Regulation of the transcription and replication cycle of human cytomegalovirus is insensitive to genetic elimination of the cognate NF-κB binding sites in the enhancer. J. Virol. 809899-9904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson, J. B., V. Misra, and T. R. Mosmann. 1976. Cytomegalovirus infectivity: analysis of the phenomenon of centrifugal enhancement of infectivity. Virology 72235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hummel, M., and M. M. Abecassis. 2002. A model for reactivation of CMV from latency. J. Clin. Virol. 25S123-S136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isomura, H., and M. F. Stinski. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early enhancer determines the efficiency of immediate-early gene transcription and viral replication in permissive cells at low multiplicity of infection. J. Virol. 773602-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isomura, H., M. F. Stinski, A. Kudoh, T. Daikoku, N. Shirata, and T. Tsurumi. 2005. Two SP1/Sp3 binding sites in the major immediate-early proximal enhancer of human cytomegalovirus have a significant role in viral replication. J. Virol. 799597-9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isomura, H., T. Tsurumi, and M. F. Stinski. 2004. Role of the proximal enhancer of the major immediate-early promoter in human cytomegalovirus replication. J. Virol. 7812788-12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan, M. C., and V. L. Mar. 1982. Spontaneous activation of latent cytomegalovirus from murine spleen explants. J. Clin. Investig. 70762-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keller, M. J., D. G. Wheeler, E. Cooper, and J. L. Meier. 2003. Role of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter's 19-base-pair-repeat cyclic AMP-response element in acutely infected cells. J. Virol. 776666-6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koedood, M., A. Fichtel, P. Meier, and P. J. Mitchell. 1995. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) immediate-early enhancer/promoter specificity during embryogenesis defines target tissues of congenital HCMV infection. J. Virol. 692194-2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krmpotic, A., M. Messerle, I. Crnkovic-Mertens, B. Polic, S. Jonjic, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1999. The immunoevasive function encoded by the mouse cytomegalovirus gene m152 protects the virus against T cell control in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1901285-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier, J. L., and M. F. Stinski. 2006. Major immediate-early enhancer and its gene products, p. 151-166. In M. J. Reddehase (ed.) Cytomegaloviruses: molecular biology and immunology. Caister Academic Press, Wymondham, United Kingdom.

- 26.Meier, J. L., and J. A. Pruessner. 2000. The human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer region is required for efficient viral replication and immediate early gene expression. J. Virol. 741602-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier, J. L., M. J. Keller, and J. J. McCoy. 2002. Requirement of multiple cis-acting elements in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer for viral gene expression and replication. J. Virol. 76313-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mocarski, E. S., and C. T. Courcelle. 2001. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication, p. 2629-2673. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 29.Netterwald, J., S. Yang, W. Wang, S. Ghanny, M. Cody, P. Soteropoulus, B. Tian, W. Dunn, F. Liu, and H. Zhu. 2005. Two gamma interferon-activated site-like elements in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter/enhancer are important for viral replication. J. Virol. 795035-5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pass, R. F. 2001. Cytomegalovirus, p. 2675-2705. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 31.Presti, R. M., J. L. Pollock, A. J. Dal Canto, A. K. O'Guin, and H. W. Virgin IV. 1998. Interferon gamma regulates acute and latent murine cytomegalovirus infection and chronic disease of the great vessels. J. Exp. Med. 188:577-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddehase, M. J., M. Balthesen, M. Rapp, S. Jonjic, I. Pavic, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1994. The conditions of primary infection define the load of latent viral genome in organs and the risk of recurrent cytomegalovirus disease. J. Exp. Med. 179185-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddehase, M. J., J. Podlech, and N. K. A. Grzimek. 2002. Mouse models of cytomegalovirus latency: overview. J. Clin. Virol. 25S23-S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandford, G. R., L. E. Brock, S. Voigt, C. M. Forester, and W. H. Burns. 2001. Rat cytomegalovirus major immediate-early enhancer switching results in altered growth characteristics. J. Virol. 755076-5083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinclair, J., and P. Sissons. 2006. Latency and reactivation of HCMV. J. Gen. Virol. 871763-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stinski, M. F., and H. Isomura. 2008. Role of the cytomegalovirus major immediate early enhancer in acute infection and reactivation from latency. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner, M., S. Jonjic, U. H. Koszinowski, and M. Messerle. 1999. Systematic excision of vector sequences from the BAC-cloned herpesvirus genome during virus reconstitution. J. Virol. 737056-7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.