INTRODUCTION

In our opinion one of the most important—and vexing—questions in clinical cardiology today can be phrased quite simply: “Why did he die on Tuesday and not on Monday?”1 Superficially, one might challenge the naiveté of such a question. But, after further examination, the query may be more profound than it initially appears because it relates to the question of the proximate precipitator of sudden cardiac death (SCD), i.e., the event that transformed an electrophysiologically stable heart into one that fibrillated. For the clinician, the answer might lie in what activity the patient engaged prior to the SCD. For example, did swimming, an argument, angina, or a febrile state precede and possibly precipitate the SCD? The translational clinician-scientist might dig deeper, peeling back another layer, and ponder the electrophysiologic mechanism by which ischemia, sympathetic stimulation or another stimulus might have triggered a ventricular tachyarrhythmia. The basic scientist, mining still further, could explore the alterations in automaticity, triggered activity, conduction and reentry in the structurally abnormal heart, the heart with a channelopathy or heart failure2, and the role of sympathetic stimulation or ischemia on these properties. Finally, on a molecular level, one could study the distribution of ion channels and the modulation of protein expression by autonomic stimulation, the influence of single nucleotide polymorphisms,3 the role of gap junctions, and other factors.

Over the next years, each of these areas will continue to undergo intense exploration to uncover answers to the fundamental question posed above.4 Hopefully, we will be better able to predict the individual at risk for SCD and how to prevent it, using new and more powerful imaging techniques (MRI, CT, PET, ECGI [noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging modality]),5 genetic and proteomic screening, and other approaches. Likely, we will find an increasing number of genetic substrates predisposing to sudden death and understand why genotype often does not predict phenotype. Such work will also lead to "repair" of electrical and contractile disorders using stem cells or other techniques. Conceivably, we might be able to ablate arrhythmogenic sites noninvasively using focused ultrasound or other external energy sources. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) will no longer be “one size fits all” as, in one direction, they will become simpler possibly with a subcutaneous implant, and in the other, more complex to monitor co-morbidities such as heart failure, atrial fibrillation, ischemia, diabetes, etc. Devices will communicate with the physician and patient and an "outpatient CCU" approach to treatment will become a reality. ICDs will become smaller, more reliable, longer lasting and, hopefully, cheaper. Widespread deployment of automated external defibrillators will reduce the appalling SCD mortality. And new therapies, perhaps better drugs (assuming pharmaceutical companies desist in creating the “son of quinidine” in one form or another), approaches to understanding arrhythmia mechanisms6 and innovative devices, will be developed to reduce cardiovascular mortality further.

THE AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

But … until we accomplish these innovations, we still have to deal with the fundamental question of why someone suffered SCD at a particular time on a particular day. While the issue is obviously quite complex, with interactions between functional, structural, and genetic factors, and alterations in action potential, calcium homeostasis, conduction, stretch, ischemia, and other factors, certainly one of the “usual suspects” is the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and altered neurohumoral signaling. It has been known for many years that, as a general rule, parasympathetic stimulation in the atrium is profibrillatory but antifibrillatory in the ventricles, while sympathetic stimulation appears to be profibrillatory for both chambers. From a clinical standpoint, it is interesting that many studies have demonstrated that increased vagal activity at the level of the sinus node, measured by heart rate variability, baroreflex sensitivity, heart rate turbulence, sinus rate during and after exercise7, 8 auger reduced risk of SCD, while decreased vagal activity identifies patients at increased risk.4 Yet, surely it is the electrical activity in the ventricles that is responsible for ventricular fibrillation. Thus, the sinus node appears to be a sort of barometer of autonomic ventricular events. It would be interesting to determine whether altered parasympathetic activity at the sinus node is reflected by the same response in the ventricles.

The actual mechanisms by which the ANS causes/prevents fibrillation, particularly in the ventricles and at the multiple research levels articulated above, remain for the most part elusive. Without question, mechanisms other than direct electrophysiologic action may be operative, such as impact on thrombogenic pathways, vulnerable plaque, stretch, ischemia, and many other factors. In this brief review, we will focus solely on some electrophysiologic responses that may be operative.

Neurohumoral signaling

A fundamental characteristic of the ANS is its “ying-yang” nature, with bidirectional modulation by each limb. At the sinus node, parasympathetic stimulation is prepotent, while the reverse occurs in the ventricles, where sympathetic effects dominate. Parasympathetic stimulation reduces norepinephrine release from sympathetic nerve terminals while also opposing post ganglionic sympathetic actions. Sympathetic stimulation counters vagal effects primarily by direct stimulation of alpha and beta receptors.9

In the normal ventricle, sympathetic stimulation shortens action potential duration and the QT interval in the scalar ECG and can reduce the dispersion of repolarization. However in pathological states associated with reduced repolarization reserve such as in heart failure and channelopathies like the long QT syndrome, sympathetic stimulation is a potent stimulus for the generation of arrhythmias, perhaps by enhancing the dispersion of repolarization or by generation of after depolarizations (see below). Parasympathetic stimulation modestly prolongs ventricular refractoriness and the QT interval in the normal heart, reflected by a longer QT interval during vagal stimulation in animal studies and during sleep in humans.10

Neurotransmitters epinephrine and norepinephrine activate cardiac adrenergic receptors, increasing systolic contractility and diastolic relaxation rate as well as accelerating heart rate and atrioventricular conduction. Beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation activates the G protein–adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–protein kinase A pathway to alter the activity of a number of ion channels and transporters (fig 1). This in turn increases both peak amplitude and rate of decline of the [Ca2+]i transient via stimulation of key Ca2+ handling proteins and shortens action potential duration via augmentation of K+ outward currents. When action potential is prolonged, e.g., heart failure and LQTS, or in mutations of the ryanodine receptor in catecholaminergic ventricular tachycardia, intracellular calcium overload can augment ionic currents underlying after depolarizations (fig 2). Sympathetic stimulation can enhance this response and, if calcium regulated currents linked to repolarization, such as the Na/Ca exchanger, become dispersed heterogeneously, can contribute to arrhythmogenesis via increased dispersion of repolarization.11

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of intracellular Ca2+ cycling and associated second messenger pathways in cardiomyocytes (figure modified from Yano et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:556–564). AC, adenylyl cyclase; α, G protein subunit α; α-receptor, α-adrenergic receptor; β, G protein subunit β; β-receptor, β-adrenergic receptor; γ, G protein subunit γ, LTCC, L-type Ca2+ channel; CaMKII, Ca2+-calmodulin kinase II; I-1, inhibitor 1; NCX, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; P, phosphate group; PLC, phosphatase 2A; ATP, SR Ca2+-ATPAse. Reproduced with permission from ref 1.

Figure 2.

Proposed scheme of events leading to DADs and triggered tachyarrhythmia. (A) Congenital (e.g., ankyrin-B mutation) and/or acquired factors (e.g., ischemia, hypertrophy, increased sympathetic tone) will cause a diastolic Ca2+ leak through RyR2, resulting in localized and transient increases in [Ca2+], in cardiomyocytes. (B) Representative series of images showing changes in [Ca2+], during a Ca2+ wave in a single cardiomyocyte loaded with a Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye. Images were obtained at 117-ms intervals. Focally elevated Ca2+ (ii) diffuses to adjacent junctional SR, where it initiates more Ca2+ release events, resulting in a propagating Ca2+ wave (iii–vii). Reproduced with permission from Subramanian et al Biophysical Journal 2001; 80:1–11. (C) The Ca2+ wave through activation of Ca2+-sensitive inward currents will depolarize the cardiomyocytes (DAD). In cardiomyocytes the inward INa/Ca is the major candidate for the transient inward current underlying DADs, although the role of the Ca2+-activated CI-current [ICl(Ca)] and a Ca2+-sensitive nonspecific cation current [INS (Ca)] cannot be excluded. If of sufficient magnitude, the DAD will depolarize the cardiomyocyte above threshold resulting in a single or repetitive premature heartbeat (red arrows), which can trigger an arrhythmia. Modified with permission from Circulation Research and Nature. Downregulation of the inward rectifier potassium current (IK1), upregulation of INa/Ca, or a slight increase in intercellular electrical resistance can promote the generation of DAD-triggered action potentials. S, stimulus. Reproduced with permission from ref 1.

Functional Anatomy

Geographic proximity of nerve endings affects neural modulation and therefore pathways of innervation are important. Parasympathetic pathways to the atria have been well characterized in dogs, and to some degree in patients, with a concentration of ganglia in various fat pads directing innervation to specific sites. In the ventricles, major sympathetic trunks appear localized in the epicardium alongside coronary arteries, with transmural penetration to innervate the rest of the myocardium. The major parasympathetic ventricular pathways are epicardial until crossing the atrioventricular groove, when vagal trunks appear to penetrate the myocardium to become located predominantly in the ventricular subendocardium (fig 3). Regional interruption of vagal and sympathetic innervation occurs after myocardial infarction and, depending on whether the infarct is transmural or subendocardial, the type and extent of neural interruption can vary. The infarction destroys nerves in the infarct zone and renders distal myocardial segments denervated or at least neurally dysfunctional. Presumably any type of myocardial injury or scarring can produce similar responses since such changes have been found in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathies, as well as in patients with ventricular tachycardia in the absence of coronary artery disease.10 Denervation supersensitivity with exaggerated shortening of ventricular effective refractory periods (ERP) and enhanced inducibility of ventricular fibrillation in the presence of catecholamines follows such changes.10 Immunohistochemical support of heterogeneous sympathetic innervation of the heart includes spatial variation in myocardial norepinephrine content,10 expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), synaptophysin and growth associated protein 43.12 Nerve sprouting following injury such as infarction and ablation13 has been shown in several animal models as well as in the explanted hearts of patients who had a history of potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias.14 Induction of sympathetic nerve sprouting by infusion of nerve growth factor into the left stellate ganglion of an experimental model of cardiac hypertrophy and infarction results in an high risk of sudden death.15

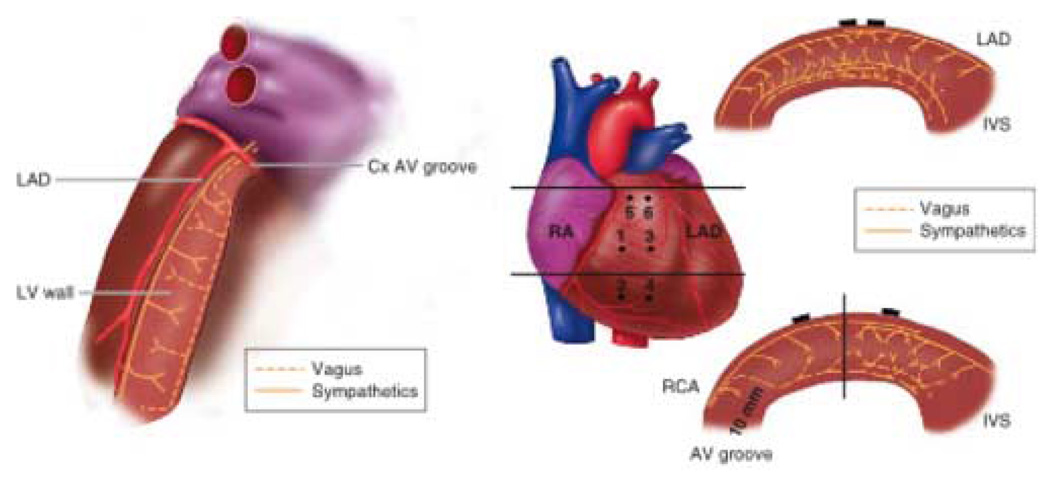

Figure 3.

Intraventricular role of sympathetic and vagal nerves to the left and right ventricles. Left. Schematic of the transverse view of the left ventricle (LV) showing functional pathways of the efferent and afferent sympathetic and vagal nerves. Right. Schematic of the transverse views of the right ventricular (RV) wall showing functional pathways of the efferent sympathetic and vagal nerves. Top right. Transverse view of the RV outflow tract at the upper horizontal line on the heart image (middle panel). Bottom right. Transverse view of the anterolateral wall at the lower horizontal line on the heart image (middle panel). The vertical solid line indicates the center of the RV anterolateral wall. Closed circles indicate position of plunge electrodes labeled 1 to 6. Cx= circumflex coronary artery; IVS = interventricular septum; LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery; RA = right atrium; RCA = right coronary artery. (Reproduced with permission from Ito M, Zipes DP Circulation 1994; 90:1459)

Mechanisms

The precise mechanism by which sympathetic hyperinnervation promotes cardiac arrhythmias is speculative. The ultimate manifestation of the arrhythmia is probably the end result of a variety of interacting factors (fig 4). Increased density of sympathetic nerve endings could augment release and cause higher than normal tissue concentrations of sympathetic neurotransmitters (e.g. norepinephrine, neuropeptide Y) during sympathetic excitation. Spatially heterogeneous electrical remodeling of the cardiomyocytes might result in an increase in L-type Ca2+ current density and decrease in K+ current densities,16 causing action potential prolongation in hyperinnervated regions. Intracellular calcium overload could give rise to triggered activity and VT/VF. Along with electrical remodeling of a number of ion channels and transporters in the surviving myocardium bordering the infarct, acute release of sympathetic neurotransmitters, through their effects on Ca2+, K+, and Cl− channels and Ca2+ transporters and enzymes, could accentuate preexisting heterogeneity of excitability and refractoriness, contributing to arrhythmia susceptibility. Norepinephrine and/or neuropeptide Y–induced arterial constriction and platelet aggregations can induce myocardial ischemia in hyperinnervated regions during emotional and/or physical stress, further promoting the vulnerability to arrhythmic events.1, 10 Finally, it is possible that surges of sympathetic discharge, such as might occur during excitement or activity, or chronic excess sympathetic stimulation, or both, might account for the harmful effects.

Figure 4.

Factors contributing to arrhythmogenesis in hearts with heterogeneous sympathetic innervation. Myocardial injury (e.g., myocardial infarction) or chronic hypercholesterolemia will cause a spatially uneven increase in sympathetic neurotransmitters. Chronic, nonuniform elevations of neurotransmitters, through alterations in the expression of L-type Ca2+ channels and K+ channels, create spatial dispersion of action potential duration. Action potential prolongation and augmented Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels combined to increase the susceptibility to EAD-and/ or DAD-triggered activity in hyperinnervated regions. If the triggered beat propagates throughout the rest of the heart, the preexisting spatial dispersion of action potential duration and, thus, myocardial refractoriness facilitate the initial of tachyarrhythmias. Locally elevated levels of neuropeptide Y and norepinephrine may increase coronary artery tone, thereby critically reducing the coronary perfusion reserve under condition of increased oxygen demand (e.g., physical and/or emotional stress) and causing regional ischemia, which contribute to the development of an arrhythmia. Reproduced with permission from ref 1.

Multiple clinical studies provide evidence supporting an adrenergic contribution to SCD: beta adrenergic blockade reduces total and SCD mortality in patients with coronary artery disease; prolonged sympathetic stimulation results in subendocardial ischemia/infarction and increases cardiac mortality; treatment of heart failure with virtually all sympathomimetic methods increases mortality; and use of dietary supplements containing sympathomimetic agents like ephedra/ephedrine can cause SCD.4 Explanted human hearts from transplant recipients with a history of arrhythmias exhibit a significantly higher and also more heterogeneous density of sympathetic nerve fibers than those of patients without arrhythmias.14

A host of animal studies, including nerve sprouting mentioned above, over many years support enhanced mortality by sympathetic stimulation and its reduction by vagal stimulation. More recent studies found that an increase in parasympathetic and/or decrease in sympathetic activity produced by spinal cord stimulation reduced spontaneous ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation (VT/VF) in a chronic infarct, heart failure canine model with superimposed acute ischemia,17 as did intrathecal clonidine.18 Rabbits given a high-cholesterol diet developed myocardial hypertrophy and cardiac sympathetic hyperinnervation without coronary artery disease, along with an increased incidence of VF, enhanced dispersion of repolarization, prolongation of action potential duration and the QT interval, and increased L-type Ca2+ current density.19

Renin-angiotensin-system

A discussion of neuroregulation must also include the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), an enzymatic cascade that controls conversion of angiotensinogen into angiotensin II. Increased levels of angiotensin II have several adverse effects on the cardiovascular system, including cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, facilitation of norepinephrine release from its prejunctional sites, fibroblast and smooth muscle proliferation, and vasoconstriction. Chronic stimulation of the angiotensin receptor–coupled Gaq–phospholipase C–PKC pathway can downregulate the activity of several key Ca2+ handling proteins via phosphatase-mediated dephosphorylation (fig 2). Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and/or angiotensin II receptor blockade decreases cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction.20 Experimental studies show that abnormal regulation of RAS in cardiovascular disease may increase the susceptibility to arrhythmias. Transgenic mice with genetically clamped elevations in angiotensin II exhibit marked cardiac hypertrophy, bradycardia due to atrioventricular conduction defects, T-wave alternans, and a high frequency of SCD from arrhythmias.21 Mice with cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of ACE–related carboxypeptidase capable of cleaving angiotensin II exhibit downregulation of connexin-40 and connexin-43, complete atrioventricular block, and an increased rate of SCD from ventricular arrhythmias, suggesting that RAS controls connexin expression in the heart.22 Alterations in the RAS also affect peripheral and central sympathetic function. In rat postganglionic sympathetic neurons, angiotensin II acutely inhibits voltage-dependent N-type Ca2+ currents and repolarizing K+ currents, 23 possibly resulting in altered excitation-secretion coupling of peripheral sympathetic neurons.

Angiotensin II directly modulates ion channels and transporters. Inhibition by angiotensin II of repolarizing K+ currents in arterial smooth muscle causes vasoconstriction, 24 possibly leading to reduced myocardial blood flow in conditions associated with elevated angiotensin II. In cardiomyocytes, enhancement of ICa.L, reduction of the delayed rectifier K+ current, IK, and the transient outward K+ current, Ito, and electrogenic Na/K ATPase activity act synergistically to prolong action potential duration and to increase intracellular Ca2+ load, thereby promoting arrhythmia susceptibility.

Angiotensin II promotes the elaboration of cytokines, growth factors and fibrosis by myofibroblasts. Similarly aldosterone and endothelin peptides are profibrotic. Myocardial norepinephrine release is promoted by angiotensin II and norepinephrine further activates RAS.

Angiotensin II also enhances release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex. Aldosterone has potent sodium-retaining properties and can exert adverse cardiovascular effects, including myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis. Like angiotensin II, aldosterone regulates cardiac ion channels. Chronic exposure of rat ventricular myocytes to aldosterone reduces and increases, respectively, transient outward potassium current (Ito) and ICa.L.25 The temporal relationship of the changes in current densities and the effect of blockers of the L-type Ca2+ current are consistent with the Ca2+-dependent reduction of Ito expression. In a postmyocardial infarction model of heart failure in rats, aldosterone antagonism had a number of effects, including inhibition of fibrosis, reduction of myocardial norepinephrine content, and increase of the VF threshold. 26 Clinically, treatment with the aldosterone receptor antagonists spironolactone or eplerenone has been demonstrated to reduce SCD in heart failure patients. 27

Collectively, these observations suggest that elevated angiotensin II and/or aldosterone levels exert adverse electrophysiological effects that can contribute to the development of a proarrhythmic substrate in conditions that are typically associated with abnormal activation of the RAS (e.g. heart failure). Antagonizing their effects could reduce the extent of adverse electrical remodeling and prevent SCD. Because RAS signaling also has profound effects on heart structure, including induction of hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis, it will be important to determine whether antiarrhythmic effects of RAS signaling antagonists derive indirectly from preservation of the structural integrity of the heart or directly from modulation of ion channels and transporters, or both.

Future

While we have learned much, many unanswered questions remain. We need to explore the molecular and cellular mechanisms regulating parasympathetic/sympathetic nerve processing in the normal and diseased heart; the short and long term effects of noncholinergic, nonadrenergic neurotransmitters, including neuropeptide Y, calcitonin gene–related product, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and substance P, on cardiomyocyte electrophysiology and Ca2+ handling, and the second messenger pathways involved; the role of calmodulin and the Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), a downstream element of the beta adrenergic receptor-initiated signaling cascade, which has been linked to pathological myocardial remodeling and regulation of key proteins involved in cardiac excitation-contraction coupling;28 ANS modulation of gap junction expression and function; the electrical properties of pre/postganglionic sympathetic/parasympathetic neurons in the diseased state, resulting in altered excitation-secretion coupling; the impact of the autonomic nervous system on electrical heterogeneity in the diseased heart; the role of the autonomic nervous system in a variety of ion channelopathies; whether sympathetic stimulation increases the incidence of abnormalities in intracellular Ca2+ handling in the whole heart [Ca2+ waves, beat-to-beat variations in Ca2+ amplitude and/or duration (alternans)] that may act as triggers of ventricular arrhythmias; and the clinical importance of alpha and beta subtypes, especially beta 3 subtype.29 These are only a sampling of issues in need of exploration, and the search will continue to be exciting.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rubart M, Zipes DP. Mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. JCI. 2005 Sep;115(9):1–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI26381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomaselli GF, Zipes DP. What causes sudden death in heart failure? Circ Res. 2004 Oct 15;95(8):754–763. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145047.14691.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubart M, Zipes DP. Genes and cardiac repolarization: the challenge ahead. Circulation. 2005 Aug 30;112(9):1242–1244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.563015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priori S, Zipes DP. Sudden Cardiac Death. Elsevier Pub; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghanem RN, Jia P, Ramanathan C, Ryu K, Markowitz A, Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI): comparison to intraoperative mapping in patients. Heart Rhythm. 2005 Apr;2(4):339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilmour RFJ, Zipes DP. New mechanisms of antiarrhythmic actions. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. 2004;1:37–41. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe J, Thamilarasan M, Blackstone EH, Thomas JD, Lauer MS. Heart rate recovery immediately after treadmill exercise and left ventricular systolic dysfunction as predictors of mortality: the case of stress echocardiography. Circulation. 2001 Oct 16;104(16):1911–1916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jouven X, Empana JP, Schwartz PJ, Desnos M, Courbon D, Ducimetiere P. Heart-rate profile during exercise as a predictor of sudden death. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 12;352(19):1951–1958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi N, Zipes DP. Vagal modulation of adrenergic effects on canine sinus and atrioventricular nodes. Am J Physiol. 1983 Jun;244(6):H775–H781. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.6.H775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubart M, Zipes DP. Genesis of cardiac arrhythmias: electrophysiological considerations. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow R, Braunwald E, editors. Heart Disease. A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 653–695. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong W, DiSilvestre D, Tomaselli G. Transmural Heterogeneity of Na+–Ca2+ Exchange: Evidence for Differential Expression in Normal and Failing Hearts. Circ. Res. 2005 Aug;97:207–209. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000175935.08283.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen PS, Chen LS, Cao JM, Sharifi B, Karagueuzian HS, Fishbein MC. Sympathetic nerve sprouting, electrical remodeling and the mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc Res. 2001 May;50(2):409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuyama Y, Pak HN, Miyauchi Y, Liu YB, Chou CC, Hayashi H, Fu KJ, Kerwin WF, Kar S, Hata C, Karagueuzian HS, Fishbein MC, Chen PS, Chen LS. Nerve sprouting induced by radiofrequency catheter ablation in dogs. Heart Rhythm. 2004 Dec;1(6):712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao JM, Fishbein MC, Han JB, Lai WW, Lai AC, Wu TJ, Czer L, Wolf PL, Denton TA, Shintaku IP, Chen PS, Chen LS. Relationship between regional cardiac hyperinnervation and ventricular arrhythmia. Circulation. 2000 Apr 25;101(16):1960–1969. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou S, Chen LS, Miyauchi Y, Miyauchi M, Kar S, Kangavari S, Fishbein MC, Sharifi B, Chen PS. Mechanisms of cardiac nerve sprouting after myocardial infarction in dogs. Circ Res. 2004 Jul 9;95(1):76–83. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000133678.22968.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heath BM, Xia J, Dong E, An RH, Brooks A, Liang C, Federoff HJ, Kass RS. Overexpression of nerve growth factor in the heart alters ion channel activity and beta-adrenergic signalling in an adult transgenic mouse. J Physiol. 1998 Nov 1;512(Pt 3):779–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.779bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Issa ZF, Zhou X, Ujhelyi MR, Bhakta D, Groh WJ, Miller JM, Zipes DP. Thoracic spinal cord stimulation reduces the risk of ischemic ventricular arrhythmias in a postinfarction heart failure canine model. Circulation. 2005 Jun 21;111(24):3217–3220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.507897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Issa ZF, Ujhelyi MR, Hildebrand KR. Intrathecal clonidine reduces the incidence of ischemia-provoked ventricular arrhythmias in a canine post-infarction heart failure model. Heart Rhythm. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.06.031. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu YB, Wu CC, Lu LS, Su MJ, Lin CW, Lin SF, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Chen PS, Lee YT. Sympathetic nerve sprouting, electrical remodeling, and increased vulnerability to ventricular fibrillation in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Circ Res. 2003 May 30;92(10):1145–1152. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000072999.51484.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Rouleau JL, Kober L, Maggioni AP, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Van de Werf F, White H, Leimberger JD, Henis M, Edwards S, Zelenkofske S, Sellers MA, Califf RM Valsartan in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial Investigators. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N Engl J Med. 2003 Nov 13;349(20):1893–1906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caron KM, James LR, Kim HS, Knowles J, Uhlir R, Mao L, Hagaman JR, Cascio W, Rockman H, Smithies O. Cardiac hypertrophy and sudden death in mice with a genetically clamped renin transgene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 2;101(9):3106–3111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307333101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donoghue M, Wakimoto H, Maguire CT, Acton S, Hales P, Stagliano N, Fairchild-Huntress V, Xu J, Lorenz JN, Kadambi V, Berul CI, Breitbart RE. Heart block, ventricular tachycardia, and sudden death in ACE2 transgenic mice with downregulated connexins. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro MS, Wollmuth LP, Hille B. Angiotensin II inhibits calcium and M current channels in rat sympathetic neurons via G proteins. Neuron. 1994 Jun;12(6):1319–1329. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelband CH, Hume JR. [Ca2+]i inhibition of K+ channels in canine renal artery. Novel mechanism for agonist-induced membrane depolarization. Circ Res. 1995 Jul;77(1):121–130. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benitah JP, Perrier E, Gomez AM, Vassort G. Effects of aldosterone on transient outward K+ current density in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2001 Nov 15;537(Pt 1):151–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0151k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cittadini A, Monti MG, Isgaard J, Casaburi C, Stromer H, Di Gianni A, Serpico R, Saldamarco L, Vanasia M, Sacca L. Aldosterone receptor blockade improves left ventricular remodeling and increases ventricular fibrillation threshold in experimental heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2003 Jun 1;58(3):555–564. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J, Gatlin M. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 3;348(14):1309–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang R, Khoo MS, Wu Y, Yang Y, Grueter CE, Ni G, Price EE, Jr, Thiel W, Guatimosim S, Song LS, Madu EC, Shah AN, Vishnivetskaya TA, Atkinson JB, Gurevich VV, Salama G, Lederer WJ, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nat Med. 2005 Apr;11(4):409–417. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou S, Paz O, Cao J-M, Asotra K, Chai N-N, Wang C, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Sharifi B, Chen P-S. Differential beta-adrenenoceptor expression induced by nerve growth factor infusion into the canine right and left stellate ganglia. Heart Rhythm. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.08.027. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]