Abstract

Dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ), a novel nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) inhibitor, has been shown to be active against variety types of solid tumours as well as haematological malignant cells. This study explored the anti-inflammatory effects of DHMEQ in vitro. DHMEQ inhibited the proliferation of phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated or alloreactive peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in mixed lymphocyte cultures as measured using a 3-(4,5-dimethylithiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay. In contrast, DHMEQ did not affect the viability of resting PBMC. In addition, real-time polymerase chain reaction showed that DHMEQ decreased PHA-stimulated expression of T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokines, including interleukin-2, interferon-γ, and tumour necrosis factor α, in PBMC as well as Jurkat T-lymphoblastic leukaemia cells, and also decreased levels of p65 isoforms of NF-κB in the nucleus. Furthermore, we found that DHMEQ inhibited the endocytic capacity of dendritic cells (DCs) and down-regulated the expression of cell surface antigen CD40, suggesting that DHMEQ blocked the maturation as well as the function of DCs. Taken together, the results suggest that DHMEQ may be useful for treatment of inflammatory diseases, including graft-versus-host disease after allogenic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Keywords: CD40, dendritic cell, DHMEQ, NF-κB, Th1 cytokine

Introduction

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the major complication after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (HST) and is a manifestation of the alloreactive response to host histocompatibility differences mediated by mature donor T cells.1–3 GVHD is induced by a three-step process in which the innate and adaptive immune systems interact. (i) The conditioning regimen with irradiation and/or chemotherapy leads to damage of host tissues throughout the body and activates the secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1).4 These cytokines enhance donor T-cell recognition of host alloantigens by increasing expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens and other molecules on host antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells (DCs). (ii) Host APCs present alloantigen in the form of a peptide human leucocyte antigen complex to the resting T cells. The interaction of APCs and donor T cells triggers costimulatroy signals, which further activate these immune cells to produce cytokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ, which primes mononuclear phagocytes to produce TNF-α and IL-1.5 (iii) Effector functions of mononuclear phagocytes and neutrophils are triggered through a secondary signal provided by mediators, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), that leaks through the intestinal mucosa damaged by irradiation and/or chemotherapy. Released inflammatory chemokines thus recruit effector cells into target organs, resulting in tissue destruction and, in some cases, death. Thus, inappropriate production of cytokines is intimately involved in the pathogenesis of acute GVHD.6,7

Nuclear factor κB is a generic term for a dimeric transcription factor formed by the hetero- or homodimerization of a number of rel family members.8 To date, five rel proteins have been identified: RelA (p65), RelB and cRel, which each have transactivation domains, and p50 and p52, which are expressed as the precursor proteins p105 (NF-κB1) and p100 (NF-κB2), respectively. These precursors require post-translational processing and do not contain transactivation domains. The most abundant and active forms of NF-κB are dimeric complexes of p50/RelA (p50/p65). NF-κB is considered to play a pivotal role in immune and inflammatory responses through the regulation of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines. These proinflammatory cytokines are thought to be critical mediators of GVHD.6,7,9–11 Therefore, a rational target for either prevention or treatment of GVHD may be NF-κB.

Dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ), a specific inhibitor of NF-κB nuclear translocation, has been shown to be active against a variety of types of solid tumours as well as haematological malignant cells.12–16

We previously showed that DHMEQ blocked TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB in Jurkat T-lymphoblastic leukaemia cells.17 These observations raised the possibility that DHMEQ might inhibit exaggerated cytokine production in inflammatory diseases such as GVHD.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin was synthesized in our laboratory.18 It was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) to produce a 10 μg/ml solution and subsequently diluted in culture medium to a final DMSO concentration of <0·1%.

Cells

The acute lymphoblastic T-cell leukaemia Jurkat cells were cultured in standard RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from healthy volunteers after informed consent had been obtained.

3-(4,5-dimethylithiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay

PBMC (4 × 106 cells/ml) from healthy volunteers were cultured in the following conditions with or without various concentrations of DHMEQ (0·5–3 μg/ml) for 3 days in 96-well plates (Flow Laboratories, Irvine, CA): (i) culture medium alone (control); (ii) culture medium plus phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, 5 μg/ml); (iii) culture medium plus irradiated (3 Gy) allogenic PBMC (4 × 106/ml). After culture, the number and viability of cells were evaluated by measuring the mitochondrial-dependent conversion of the MTT salt (Sigma) to a coloured formazan product. All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

Assessment of apoptosis

PBMC were plated at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml and incubated with PHA (5 μg/ml) or various concentrations of DHMEQ (0·5–3 μg/ml) either alone or in combination in 12-well plates (Flow Laboratories). The ability of DHMEQ to induce apoptosis of PHA-stimulated PBMC was measured using an annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA).

Generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells

Dendritic cells were generated by differentiation of PBMC in the presence of 50 ng/ml granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Sigma) and 10 ng/ml IL-4 (Sigma). The medium was replenished with cytokines every other day. Maturation of differentiated DCs was accomplished by treating with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) (Sigma) for another 2 days. On day 5 of culture, 0·5 μg/ml DHMEQ was added to determine whether DHMEQ blocked maturation of DCs. Cells were harvested for further experiments at day 7 of culture.

Flow cytometry analysis

To determine whether DHMEQ blocks maturation of DCs, levels of the CD40 antigen on the cell surface of DCs were measured using flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CD40 monoclonal antibody and the PE mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) K isotype control were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Live cells (1 × 104) were gated and analysed.

Analysis of endocytic capacity

For the analysis of endocytic activity, 1 × 105 cells were incubated with fluorescein (FITC)-dextran [molecular weight (MW) 40 000; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany] for 1 hr at 37°C. For the isotype control, FITC mouse IgG1 (eBioscience) was used. The cells were washed 4 times and immediately analysed on a FACSCalibur cytometer.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

RNA isolation and cDNA preparation were performed as described previously.19 Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) as described previously.19 Primers for PCR are shown in Table 1. PCR conditions for all genes were as follows: a 95°C initial activation for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds, and fluorescence determination at the melting temperature of the product for 20 seconds on an ABI PRISM 7000 (Applied Biosystems).

Table 1.

Polymerase chain reaction primers

| Proteins | Directions | Primers |

|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | Forward | 5′-TGCAACTCCTGTCTTGCATT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCAGCAGTAAATGCTCCAG-3′ | |

| IFN-γ | Forward | 5′-TCATCCAAGTGATGGCTGAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CTTCGACCTCGAAACAGCAT-3′ | |

| TNF-α | Forward | 5′-CCTCCTCTCTGCCATCAAGA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGAAGACCCCTCCCAGATAG-3′ | |

| 18S | Forward | 5′-AAACGGCTACCACATCCAAG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTTA-3′ |

IFN, interferon; IL, interlekin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously.19 Cells were suspended in ice-cold extraction buffer containing 20 mmol/l HEPES (pH 7·9), 20% glycerol, 10 mmol/l NaCl, 0·2 mol/l ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (pH 8·0), 1·5 mmol/l MgCl2, 0·1% Triton X-100, 1 mmol/l dithiothreitol (DTT), 100 μg/ml phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. After 10 min of incubation on ice, nuclei were collected by a short spin in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant was saved as a cytoplasmic fraction, and the nuclei were resuspended in ice-cold extraction buffer containing 300 mmol/l NaCl. After 30 min of incubation, the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 1018 g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were quantified using a Bio-Rad assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Proteins were resolved on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel, transferred to an immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), and probed sequentially with antibodies. Anti-IκBα (Imgenex, San Diego, CA), anti-phospho-IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), the anti-p65 subunit of NF-κB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-histone H1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-α-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies were used.

Statistical analysis

Within treatments, groups were compared in a paired t-test using spss software (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan). To assess the difference between two groups across treatments, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Boneferroni's multiple comparison test was performed using prism statistical analysis software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The results were considered to be significant when the P-value was < 0·05, and highly significant when the P-value was < 0·01.

Results

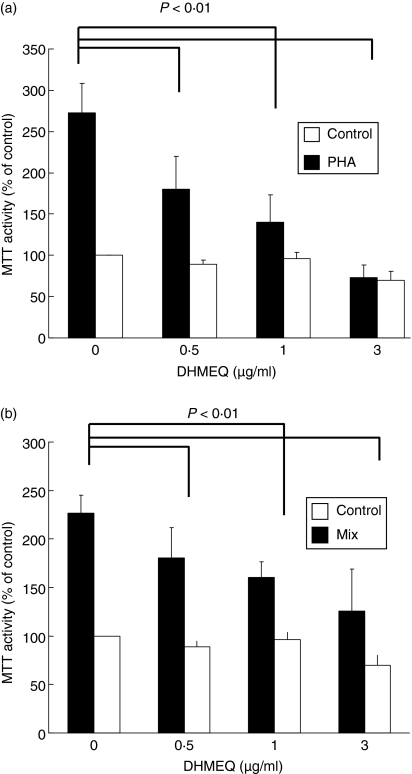

DHMEQ inhibits proliferation of PHA-stimulated or alloreactive PBMC

To examine whether DHMEQ affects proliferation or survival of PBMC, MTT assays were performed on resting, PHA-stimulated, or alloreactive PBMC (Figs 1a,b). Exposure of PBMC to PHA (5 μg/ml, 3 days) increased their proliferation by approximately 2·7-fold (Fig. 1a). DHMEQ (0·5–3 μg/ml, 3 days) inhibited PHA-stimulated proliferation of PBMC in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1a). Similarly, DHMEQ (0·5–3 μg/ml, 3 days) significantly decreased alloreactive proliferation of PBMC in a dose-dependent manner, although inhibition was less potent than that induced in PHA-stimulated PBMC (Fig. 1b). Of note, DHMEQ did not affect the viability of resting PBMC under identical culture conditions (Figs 1a,b).

Figure 1.

Dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ) induces proliferation of alloreactive (A) or phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). (a) PBMC from healthy volunteers (n = 4) were cultured with PHA (5 μg/ml) or various concentrations of DHMEQ (0·5–3 μg/ml) either alone or in combination. Their viability was assessed in a 3-(4,5-dimethylithiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay on day 3 of culture. (b) PBMC were obtained from healthy volunteers (n = 5) and were cultured with irradiated (3 Gy) allogeneic PBMC. These cells were exposed to various concentrations of DHMEQ (0·5–3 μg/ml). Their viability was assessed in an MTT assay on day 3 of culture. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for 4 (a) or 5 (b) experiments performed in triplicate plates. The statistical significance was assessed in a paired t-test.

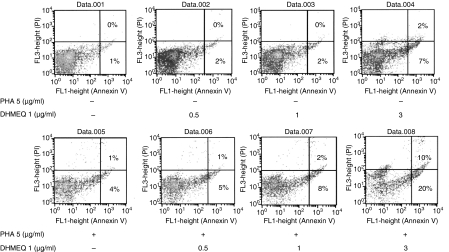

DHMEQ induces apoptosis of PHA-stimulated PBMC

To investigate the mechanism by which DHMEQ inhibits the proliferation of activated PBMC, we utilized annexin V staining. Approximately 9% of cells became annexin V positive after incubation with DHMEQ (3 μg/ml, 24 hr) (Fig. 2). When cells were exposed to PHA (5 μg/ml, 24 hr) in combination with DHMEQ (3 μg/ml, 24 hr), the annexin V-positive population increased by 30% (Fig. 2), suggesting that DHMEQ induced apoptosis of PHA-stimulated PBMC.

Figure 2.

Dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ) induces apoptosis of phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). PBMC from healthy volunteers were cultured with PHA (5 μg/ml) or various concentrations of DHMEQ (0·5–3 μg/ml) either alone or in combination. After 24 hr, cells were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide (PI), and analysed by flow cytometry. The result represents one of three experiments performed independently.

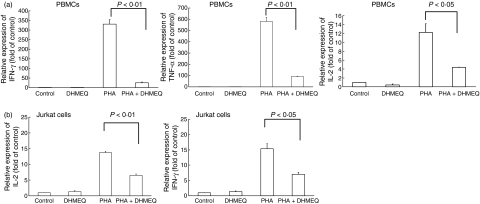

Effect of DHMEQ on PHA-stimulated expression of cytokine genes

Increased levels of cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α, are associated with the pathogenesis of acute GVHD.6,7,9–11 In order to investigate the effect of DHMEQ on PHA-stimulated cytokine production, PBMC (4 × 106 cells/ml) from healthy donors were cultured with or without DHMEQ (1 μg/ml) for 3 hr and then exposed, or not exposed, to PHA (5 μg/ml, 3 hr). Exposure of PBMC to PHA greatly stimulated expression of IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNF-α (Fig. 3a). Pre-incubation of these cells with DHMEQ (1 μg/ml, 3 hr) greatly reduced PHA-stimulated expression of these cytokine genes (Fig. 3a). Similarly, PHA increased expression of IL-2 and IFN-γ in Jurkat cells and pre-incubation of these cells with DHMEQ (1 μg/ml) decreased these levels by approximately half (Fig. 3b). DHMEQ alone did not affect cytokine production in unstimulated PBMC (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3.

Effect of dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ) on phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated expression of inflammatory cytokine genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). PBMC form healthy volunteers (a) (n = 3) or Jurkat cells (b) were pretreated with either DHMEQ (1 μg/ml) or control diluent for 3 hr and then exposed, or not exposed, to PHA (5 μg/ml) for 3 hr. Cells were harvested and RNA was extracted. cDNAs were synthesized and subjected to real-time polyerase chain reaction (PCR) using SYBR Green nucleic acid gel staining solution to measure the levels of interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-2 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in these cells. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three experiments with triplicate dishes per experimental point. The statistical significance was determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Boneferroni's multiple comparison test.

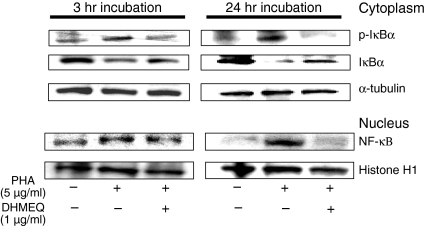

Effect of DHMEQ on PHA-stimulated NF-κB activity in Jurkat cells

Expression of cytokine genes is regulated by NF-κB. Activation of NF-κB involves two important steps: (i) phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκBα caused by IκBα kinase, resulting in release of NF-κB, and (ii) the nuclear translocation of the activated NF-κB. To elucidate the effect of DHMEQ on these steps, we measured the levels of NF-κB proteins in the nucleus and the levels of IκBα proteins in the cytoplasm in Jurkat cells after exposure to PHA alone or in combination with DHMEQ. Jurkat cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured with either DHMEQ (1 μg/ml) or control diluent. After 3 hr, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and exposed to PHA (5 μg/ml) for 3 or 24 hr. Exposure of Jurkat cells to PHA increased levels of NF-κB in the nucleus. When PHA was combined with DHMEQ, PHA-stimulated up-regulation of NF-κB was blocked. Concurrently, DHMEQ inhibited PHA-stimulated phosphorylation of IκBα and down-regulation of IκBα in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4), suggesting that DHMEQ blocked PHA-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB in Jurkat cells via inhibition of degradation of IκBα. These observations are reminiscent of our previous studies showing that DHMEQ blocked TNF-α-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB in Jurkat cells.17

Figure 4.

Effect of dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ) on nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). Jurkat cells were pretreated with either DHMEQ (1 μg/ml) or control diluent for 3 hr and then exposed to phytohaemagglutinin (5 μg/ml) for the indicated time periods. Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of these cells were prepared and subjected to western blot analysis to measure the level of IκBα, phospho-ΙκΒα and p65 of NF-κB, respectively. α-tubulin or histone H1 expression was used as a loading control.

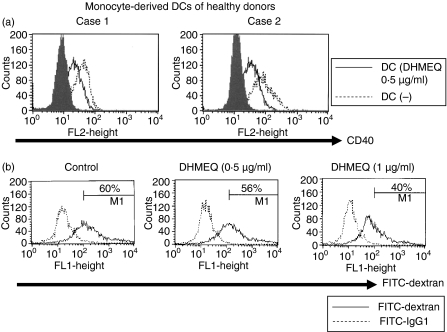

Effect of DHEMQ on maturation of DCs

NF-κB regulates the differentiation and activation of DCs,20,21 which plays a pivotal role in initiation of GVHD. We therefore explored whether DHMEQ affected maturation of DCs. For this purpose, we measured levels of CD40 antigen on the cell surface of DCs. Increased expression of CD40 is associated with maturation of DCs.20,21 As we expected, DHMEQ decreased levels of TNF-α-stimulated expression of CD40 in monocyte-derived DCs (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) Cell surface expression of CD40 on monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DCs). Monocyte-derived DCs were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy volunteers (n = 2) by culture in the presence of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (50 ng/ml) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) (10 ng/ml) for 5 days. These cells were then exposed to tumour necrosis factor α (10 ng/ml) either alone or in combination with dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ) (0·5 μg/ml). After 2 days, DCs were harvested, stained with anti-CD40 antibody and analysed by flow cytometry. The figure represents one of three experiments performed independently. (b) Exposure of DCs to DHMEQ reduces endocytic capacity. Monocyte-derived DCs were generated from PBMC by culture in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 for 5 days. These cells were then exposed to DHMEQ (0·5 or 1 μg/ml). After 2 days, cells were cultured with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran for 1 h at 37°C, washed 4 times, and analysed by flow cytometry. The figure represents one of two experiments performed independently. IgG1, immunoglobulin G1.

Effect of DHMEQ on endocytic capacity of DCs

We also explored whether DHMEQ affected the function of DCs. We monitored the capacity of DCs to internalize FITC-labelled dextran as an assay of DC endocytic capacity (Fig. 5b). To this end, we decided to use immature DCs because these normally show a much greater internalization capacity than mature DCs.20,21 Exposure of DCs to DHMEQ (0·5 or 1 μg/ml) reduced their endocytic ability (Fig. 5b), suggesting that DHMEQ may affect DC function by impeding antigen uptake for further processing and presentation.

Discussion

In this study, we found that DHMEQ, a novel NF-κB inhibitor, inhibited proliferation of both PHA-stimulated and alloreactive PBMC (Fig. 1). In addition, DHMEQ inhibited expression of Th1 cytokines in these cells (Fig. 3). Furthermore, DHMEQ blocked the maturation of DCs and reduced their endocytic capacity (Fig. 5a,b). Mature DCs express high levels of CD40 and act as APCs.20,21 Antigen recognition by T cells induces the expression of CD40 ligand (CD40L). CD40L engages CD40 on APCs and stimulates the secretion of cytokines which further activate T cells.22,23 The interaction of CD40L on T cells with CD40 on DCs thus initiates the uncontrolled immunoreaction involved in GVHD. Hence, blocking of the maturation of DCs by DHMEQ may be of use in preventing and/or treating GVHD.

Previously, we showed that DHMEQ down-regulated LPS-stimulated expression of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-12, IL-1β and TNF-α, and blocked nuclear translocation of NF-κB in murine macrophage RAW264·7 cells.24 The study also showed that DHMEQ blunted the function of RAW264·7 cells; DHMEQ inhibited phagocytosis of Escherichia coli in these cells.24 In addition, we demonstrated that DHMEQ decreased the severity of collagen-induced arthritis in a murine model.25 More recently, we showed that DHMEQ prevented allograft rejection and prolonged allograft survival, in addition to inhibiting the mixed lymphocyte reaction, and decreased the production of IFN-γ in a murine cardiac transplantation model.26 These observations augment evidence that DHMEQ possesses anti-inflammatory activity.

Recent in vitro studies performed by other investigators demonstrated that bortezomib (PS-341; Velcade; Millenium Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA), a proteasome inhibitor, possessed anti-inflammatory activity; bortezomib inhibited the proliferation of alloreactive T lymphocytes and decreased the production of Th1 cytokines.27 Another group found that bortezomib inhibited the cytokine production and endocytic capacity of DCs.28 Moreover, bortezomib protected mice from lethal GVHD and reduced serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.29,30 Of note, bortezomib did not compromise donor engraftment.29,30 Bortezomib is a well-known NF-κB inhibitor and induces apoptosis of various types of cancer in which NF-κB is activated.31 The more selective NF-κB inhibitor PS1145, an inhibitor of IκB Kinase (IKK), also succeeded in managing GVHD in the murine model.29 Together with our observations, these findings suggest that NF-κB may be a critical mediator of GVHD, and this nuclear transcription factor is a promising molecular target for the prevention or treatment of GVHD.

Taken together, our results suggest that DHMEQ, a novel NF-κB inhibitor, may be useful for the prevention or treatment of GVHD. Further studies are warranted to clarify the mode of action of this agent in inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Fund for Academic Research of Kochi University.

Abbreviations

- DHMEQ

dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylithiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium

- GVHD

graft-versus-host disease

- DCs

dendritic cells

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor alpha

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- PHA

phytohaemagglutinin

References

- 1.Hakim FT, Mackall CL. The immune system: effector and target of graft-versus-host disease. In: Ferrara JLM, Deeg HJ, Burakoff SJ, editors. Graft-vs-Host Disease. 2. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 257–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara JL, Levy R, Chao NJ. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of acute graft-vs-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1999;5:347–56. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(99)70011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korngold R. Biology of graft-vs.-host disease. Am J Ped Hematol/Oncol. 1993;15:18–27. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xuu CQ, Thompson JS, Jennings CD, Brown SA, Widmer MB. Effect of total body irradiation, busulfan-cyclophoshamide, or cyclophosphamide conditioning on inflammatory cytokine release and development of actute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in H-2-incompativle taransplanted SCID mice. Blood. 1994;83:2360–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teshima T, Ordemann R, Reddy P, Gagin S, Liu C, Cooke KR, Ferrara JL. Acute graft-versus-host disease does not require alloantigen expression on host epithelium. Nat Med. 2002;8:575–81. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antin JH, Ferrara JL. Cytokine dysregulation and acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1992;80:2964–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-κB activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill GR, Teshima T, Rebel VI, Krijanovski OI, Cooke KR, Brinson YS, Ferrara JL. The p55 TNF-alpha receptor plays a critical role in T cell alloreactivity. J Immunol. 2000;164:656–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy P, Teshima T, Kukuruga M, Ordemann R, Liu C, Lowler K, Ferrara JL. Interleukin-18 regulates acute graft-versus-host disease by enhancing Fas-mediated donor T cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1433–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrara JL, Abhyankar S, Gilliland DG. Cytokine storm of graft-versus-host disease: a critical effector role for interleukin-1. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:1216–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umezawa K. Inhibition of tumor growth by NF-kappaB inhibitors. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:990–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi E, Horiguchi Y, Nakashima J, et al. Suppression of hormone-refractory prostate cancer by a novel nuclear factor kappaB inhibitor in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:107–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumoto G, Namekawa J, Muta M, Nakamura T, Bando H, Tohyama K, Toi M, Umezawa K. Targeting of nuclear factor kappaB pathways by dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin, a novel inhibitor of breast carcinomas: antitumor and antiangiogenic potential in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1287–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe M, Ohsugi T, Shoda M, et al. Dual targeting of transformed and untransformed HTLV-1-infected T cells by DHMEQ, a potent and selective inhibitor of NF-kappaB, as a strategy for chemoprevention and therapy of adult T-cell leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:2462–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horie R, Watanabe M, Okamura T, et al. DHMEQ, a new NF-kappaB inhibitor, induces apoptosis and enhances fludarabine effects on chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2006;20:800–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ariga A, Namekawa J, Matsumoto N, Inoue J, Umezawa K. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced nuclear translocation and activation of NF-kappa B by dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24625–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki Y, Sugiyama C, Ohno O, Umezawa K. Preparation and biological activities of optically active dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin, a novel NF-kB inhibitor. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7061–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikezoe T, Yang Y, Heber D, Taguchi H, Koeffler HP. PC-SPES: potent inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappa B rescues mice from lipopolysaccharide-induced septic shock. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1521–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;19:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carvalho-Pinto CE, Garcia MI, Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Martin-Caballero J, Flores J, Martinez AC, Balomenos D. Autocrine production of IFN-gamma by macrophages controls their recruitment to kidney and the development of glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:1058–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lalor PF, Shields P, Grant A, Adams DH. Recruitment of lymphocytes to the human liver. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:52–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki E, Umezawa K. Inhibition of macrophage activation and phagocytosis by a novel NF-kappaB inhibitor, dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:578–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakamatsu K, Nanki T, Miyasaka N, Umezawa K, Kubota T. Effect of a small molecule inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB nuclear translocation in a murine model of arthritis and cultured human synovial cells. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:1348–59. doi: 10.1186/ar1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueki S, Yamashita K, Aoyagi T, et al. Control of allograft rejection by applying a novel nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitor, dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin. Transplantation. 2006;82:1720–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250548.13063.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanco B, Perez-Simon JA, Sanchez-Abarca LI, et al. Bortezomib induces selective depletion of alloreactive T lymphocytes and decreases the production of Th1 cytokines. Blood. 2006;107:3575–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nencioni A, Schwarzenberg K, Brauer KM, Schmidt SM, Ballestrero A, Grunebach F, Brossart P. Proteasome inhibitor bortezomib modulates TLR4-induced dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2006;108:551–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vodanovic-Jankovic S, Hari P, Jacobs P, Komorowski R, Drobyski WR. NF-{kappa}B as a target for the prevention of graft versus host disease: comparative efficacy of bortezomib and PS-1145. Blood. 2006;107:827–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun K, Welniak LA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Inhibition of acute graft-versus-host disease with retention of graft-versus-tumor effects by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8120–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401563101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson PG, Mitsiades C, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Bortezomib: proteasome inhibition as an effective anticancer therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:33–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.042905.122625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]