Abstract

Two pathways from the superior colliculus (SC) to the tree shrew pulvinar nucleus have been described, one in which the axons terminate in dense (or specific) patches and one in which the axon arbors are more diffusely organized (Luppino et al. [1988] J. Comp. Neurol. 273:67– 86). As predicted by Lyon et al. ([2003] J. Comp. Neurol. 467:593– 606), we found that anterograde labeling of the diffuse tectopulvinar pathway terminated in the acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-rich dorsal pulvinar (Pd), whereas the specific pathway terminated in the AChE-poor central pulvinar (Pc). Injections of retrograde tracers in Pd labeled non-γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic wide-field vertical cells located in the lower stratum griseum superficiale and stratum opticum of the medial SC, whereas injections in Pc labeled similar cells in more lateral regions. At the ultrastructural level, we found that tectopulvinar terminals in both Pd and Pc contact primarily non-GABAergic dendrites. When present, however, synaptic contacts on GABAergic profiles were observed more frequently in Pc (31% of all contacts) compared with Pd (16%). Terminals stained for the type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter, a potential marker of tectopulvinar terminals, also contacted more GABAergic profiles in Pc (19%) compared with Pd (4%). These results provide strong evidence for the division of the tree shrew pulvinar into two distinct tectorecipient zones. The potential functions of these pathways are discussed. J. Comp. Neurol. 510:24 – 46, 2008.

Indexing terms: synapse, ultrastructure, GABA, pulvinar nucleus, superior colliculus, vesicular glutamate transporter, Tupaia belangeri

Parallel visual pathways from the retina to the cortex, relayed via the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN), or the superior colliculus (SC) and pulvinar nucleus, likely serve distinct functions in the coding of form, movement, and spatial location signals. In the dLGN, further segregations of anatomically and physiologically distinct visual pathways have been identified and extensively characterized (Sherman, 1985). Likewise, studies in a variety of species have provided evidence for the existence of multiple pathways from the SC to the thalamus (May, 2006), although these pathways are largely uncharacterized, and their functions are unclear. The tree shrew, with its expanded tectopulvinar system, is good choice for studies of how pathways from the SC influence cortical activity via their projections to the pulvinar nucleus.

In 1988, Luppino et al. labeled tectothalamic terminals in the tree shrew by placing small injections of axonal tracers in the SC and discovered that the pulvinar nucleus receives input from two distinct pathways that differ in their patterns of termination. A dorsal subdivision of the pulvinar nucleus (recently termed Pd; Lyon et al., 2003) received a “diffuse” projection from the SC. That is, most of the Pd was filled with terminals irrespective of the size or location of the SC injection site. In contrast, a second zone of the pulvinar nucleus (recently termed Pc; Lyon et al., 2003) exhibited dense, spatially restricted patches of labeled terminals following the same injections in the colliculus, and their location varied with the location of the injection site.

We recently examined the synaptic organization of two tectorecipient zones of the cat thalamus (Kelly et al., 2003). We found that tectal terminals in the medial subdivision of the lateral posterior (LPm) primarily surrounded and made synaptic contacts with thalamocortical cell dendrites, whereas tectal terminals in the lateral edge of the lateral subdivision (LPl-2; Chalupa and Abramson, 1989) formed more complex synaptic arrangements that included interneurons. In the current study, we sought to determine whether the synaptic organizations of the diffuse and specific tectorecipient zones of the tree shrew pulvinar nucleus are distinct. We placed tracer injections in the SC to label tectopulvinar terminals by anterograde transport and tracer injections into the pulvinar nucleus to label tectopulvinar cells by retrograde transport. Finally, we used immunocytochemical labeling for the type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter (vGLUT2) as an alternative method to validate the distinction between the two tectopulvinar pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In total 19 adult (average weight 185 g) tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri), 9 male and 10 female, were used for these experiments. To label tectopulvinar cells by retrograde transport, 6 tree shrews received an injection of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA), and 3 tree shrews received an injection of fluorogold (FG) in the pulvinar nucleus. To label tectopulvinar terminals by anterograde transport, 3 tree shrews received an injection of BDA in the SC. Selected sections from each injected tree shrew brain were stained for acetylcholinesterase (AChE). Tissue from 7 uninjected tree shrew brains was stained with an antibody against the type 1 vesicular glutamate transporter (vGLUT1), vGLUT2, AChE, or glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). All methods were approved by the University of Louisville Animal Care and Use Committee and conform to the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Tracer injections

Tree shrews that received BDA (3,000 MW; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) or FG (Fluorochrome LLC, Denver, CO) injections were initially anesthetized with intramuscular injections of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (6.7 mg/kg). Additional supplements of ketamine and xylazine were administered approximately every 45 minutes to maintain deep anesthesia through completion of the tracer injections. Prior to injection, the tree shrews were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus and prepared for sterile surgery. A small area of the skull overlying the pulvinar nucleus (BDA: cases 4-05-5, 1-02-1AB, 9-04-1AB, 10-04-1AB, 8-06-1D, 5-06-6AB; FG: cases 5-06-5AB, 10-04-2AB, 11-05-1AB) or SC (cases 9-00-6UT, 12-01-1, 11-01-1AB) was removed and the dura reflected. For all of the pulvinar injections, and two of the SC injections, a glass pipette containing either BDA (5% in saline, tip diameter 3 μm) or FG (2% in saline, tip diameter 10 μm) was lowered vertically and the tracer was ejected iontophoretically (2 μA positive current for 15–30 minutes). For two other SC injections, a 1-μl Hamilton syringe was lowered vertically, and 0.1 μl (10% BDA in deionized water) was injected via pressure. After a 7-day survival period, the tree shrews were given an overdose of ketamine (600 mg/kg) and xylazine (130 mg/kg) and were perfused through the heart with Tyrode solution, followed by a fixative solution of 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde (BDA cases) or 4% paraformaldehyde (FG cases) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (PB).

The brain was removed from the skull, sectioned into slices 50 μm thick with a vibratome, and placed in PB. In some cases, sections were preincubated in 10% methanol in PB with 3% hydrogen peroxide (to react with the endogenous peroxidase activity of red blood cells not removed during the perfusion). The BDA was revealed by incubating sections in a 1:100 dilution of avidin and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (ABC; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in phosphate-buffered saline (0.01 M PB with 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4; PBS) with 1% normal goat serum (NGS) overnight at 4°C. The sections were subsequently rinsed, reacted with nickel-intensified 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 5 minutes, and washed in PB. FG was revealed with a rabbit anti-FG antibody (Fluorochrome LLC) diluted 1:50,000, followed by a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody, ABC, and DAB reaction. Sections were then mounted on slides for light microscope examination (BDA and FG injections) or were prepared for electron microscopy (BDA injections).

Antibody characterization

The antibodies used in this study are listed in Table 1. Preabsorption of the vGLUT1 antiserum with immunogen peptide eliminates all immunostaining (manufacturer’s product information). Western blot of rat cerebral cortex tissue reveals a single band at approximately 60 kDa (Melone et al., 2005). With the vGLUT1 antibody, the thalamic staining pattern in the tree shrew brain is similar to that obtained in rat by Kaneko and Fujiyama (2002).

TABLE 1.

Primary Antibodies Used in This Study

| Antigen | Dilution | Host species | Source | Catalog No. | Immunogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vGLUT1 | 1:7,500-1:10,000 | Guinea pig | Chemicon Temecula, CA | AB5905 | Amino acid residues 541–560 of rat vGLUT1 |

| vGLUT2 | 1:7,500-1:10,000 | Guinea pig | Chemicon Temecula, CA | AB5907 | Amino acid residues 565–582 of rat vGLUT2 |

| GAD67 | 1:2,000 | Mouse | Chemicon Temecula, CA | MAB5406 | Amino acids residues 4–101 of human GAD67 |

| GABA | 1:2,000 | Rabbit | Sigma, St. Louis, MO | A2052 | GABA conjugated to bovine serum albumin using glutaraldehyde |

| Fluoro-Gold | 1:50,000 | Rabbit | Fluorochrom, Denver, CO | Antibody to Fluoro-Gold | Fluoro-Gold |

Preabsorption of the vGLUT2 antiserum with immunogen peptide eliminates all immunostaining (manufacturer’s product information). Western blot of cultured astrocytes from rat visual cortex reveals a single band at approximately 62 kDa (Montana et al., 2004). The vGLUT2 antibody has been demonstrated to stain geniculocortical terminals in the ferret (Nahmani and Erisir, 2005). This was accomplished by staining sections containing geniculocortical terminals labeled by anterograde transport with the vGLUT2 antibody and using confocal microscopy to establish colocalization. The size, ultra-structure, and synaptic targets of vGLUT2-labeled terminals were also found to be similar to those of geniculocortical terminals labeled by anterograde transport. In addition, vGLUT2 did not colocalize with corticocortical axons. In tree shrew striate cortex, the vGLUT2 antibody labels a dense band of terminals in layer 4, the major target of geniculocortical terminals (Raczkowski and Fitzpatrick, 1990).

The GAD antibody recognizes a single band at 67 kDa on Western blot analysis of rat brain (manufacturer’s unpublished information). The GABA antibody shows positive binding with GABA and GABA-keyhole limpet hemocyanin, but not bovine serum albumin (BSA), in dot blot assays (manufacturer’s product information). In tree shrew tissue, the GAD and GABA antibodies stain most neurons in the thalamic reticular nucleus and a subset of neurons in the dorsal thalamus. This labeling pattern is consistent with other GABAergic markers used in a variety of species (Houser et al., 1980; Oertel et al., 1983; Fitzpatrick et al., 1984; de Biasi et al., 1986; Montero and Singer, 1984, 1985; Rinvik et al., 1987; Rinvik and Ottersen, 1988). All Fluoro-Gold antibody binding was confined to cells that contained Fluoro-Gold (as determined by their fluorescence under ultraviolet illumination).

Immunocytochemistry

Tissue from 5 tree shrews was immunoreacted to reveal the distribution of vGLUT1 and vGLUT2 (cases 4-00-1UT, 9-00-7UT,1-02-2UT, 9-00-3UT, and 9-00-4UT), and tissue from 4 tree shrews was stained to reveal the distribution of GAD (cases 3-05-5, 4-05-4, 9-00-3UT, and 5-06-5AB). The tree shrews were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of ketamine and xylazine, or sodium pentobarbital (125 mg/kg), and perfused through the heart with Tyrode solution, followed by a fixative solution of 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde (4-00-1UT and 9-00-7UT) or 4% paraformaldehyde (cases 3-05-5, 4-05-4, 1-02-2UT, 9-00-3UT, and 9-00-4UT) in PB.

To reveal the distribution of GAD, sections were processed using immunocytochemical protocols previously described (Bickford et al., 1999; Baldauf et al., 2005). To reveal the distribution of vGLUT1 and vGLUT2, 50-μm-thick vibratome sections were preincubated in 10% NGS in PBS for 30 minutes and then incubated overnight at 4°C in solutions containing dilutions of the anti-vGLUT1 or anti-vGLUT2 antibodies. In the rat, these antibodies have been found to stain glutamatergic terminals of cortical and subcortical origins, respectively (Fujiyama et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001). Incubated sections were subsequently rinsed in PB and placed in a 1:100 dilution of biotinylated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (Vector Laboratories) in 1% NGS/PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then washed in PB and placed in ABC for 1 hour, reacted with nickel-enhanced DAB, and mounted on slides or prepared for electron microscopy.

In one case (5-06-5AB), sections that contained FG-labeled tectopulvinar cells were reacted to reveal the distribution of GAD cells in the SC. The GAD antibody was tagged with a biotinylated goat anti-mouse antibody (1: 100; Vector Laboratories) followed by a 1:100 dilution of streptavidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probe, Eugene, OR). In the same sections, the FG was tagged with the FG antibody and a goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546 (1:100; Molecular Probes). The sections were subsequently mounted on slides for viewing with a confocal microscope.

Sections cut for ultrastructural analysis (described below) were stained for the presence of GABA using previously reported postembedding immunocytochemical techniques (Patel and Bickford, 1997; Datskovskaia et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2002; Dankowski and Bickford, 2003; Li et al., 2003). The GABA antibody was tagged with a goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to 15-nm gold particles (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

AChE staining

Alternate sections from 12 cases were stained for AChE to distinguish the Pd zone of the pulvinar nucleus (Lyon et al., 2003). The sections were taken from cases in which adjacent sections were either stained for GAD (3-05-5, 4-05-4, and 9-00-3UT) or stained to reveal BDA transported from pulvinar injections (4-05-5, 1-02-1AB, 9-04-1AB, 10-04-1AB, 8-06-1D, and 5-06-6AB) or from SC injections (9-00-6UT, 12-01-1, and 11-01-1AB). We used a protocol modified from Geneser-Jensen and Blackstad (1971). Briefly, the tissue was rinsed in deionized water, placed in a solution of acetylcholinesterase for 3 hours, and then rinsed in saline, followed by deionized water, before reacting with a 1.25% sodium sulfite solution for 1 minute. After deionized water rinses, the tissue was then incubated in a 1% silver nitrate solution for 5 minutes, rinsed with deionized water, and placed in a 0.85% sodium thiosulfite solution to adjust the contrast of the tissue staining (approximately 5 minutes). Finally, the tissue was rinsed in saline and mounted on slides for light microscopic examination.

Data analysis

A Neurolucida system and tracing software (Micro-BrightField, Inc., Williston, VT) were used to plot the distribution of tectopulvinar cells, tectopulvinar terminals, and GAD-stained cells in the pulvinar nucleus and dLGN. In some cases, adjacent sections stained for AChE were used to distinguish the borders of the Pd. The density of GAD-stained cells in Pd, Pc, and dLGN was calculated in Neurolucida Explorer software.

Electron microscopy

Sections labeled by the anterograde transport of BDA or vGLUT2 immunohistochemistry were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in an ethyl alcohol series, and flat embedded in Durcupan resin between two sheets of Aclar plastic (Ladd Research, Williston, VT). Durcupan-embedded sections were first examined with a light microscope to select areas for electron microscopic analysis. Selected areas were mounted on blocks, ultrathin sections (70 – 80 nm, silver-gray interference color) were cut using a diamond knife, and sections were collected on Formvar-coated nickel slot grids.

Selected sections were stained for the presence of GABA as described above. The GABA-stained sections were air dried and stained with a 10% solution of uranyl acetate in methanol for 30 minutes before examination with an electron microscope.

Ultrastructural analysis

Ultrathin sections were examined using an electron microscope. All labeled terminals involved in a synapse were photographed within each examined section. The pre- and postsynaptic profiles were characterized on the basis of size (shortest diameter and area measured using a digitizing tablet and Sigma Scan Software; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), the presence or absence of vesicles, and gold particle density. The ultrastructural features of adjacent terminals were also noted. In tissue that contained BDA-labeled tectopulvinar terminals, profiles were considered to be GABAergic if the gold particle density was higher than that found overlying 95% of the small profiles with round vesicles (RS profiles) photographed within the same tissue. In tissue that contained vGLUT2-stained terminals, profiles were considered to be GABAergic if the gold particle density was higher than that overlying 100% of the vGLUT2-stained terminals.

Computer-generated figures

Light-level photographs were taken with a digitizing camera (Spot RT; Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). Confocal images were taken with an Olympus Fluoview laser scanning microscope (BX61W1). Electron microscopic images were taken with a digitizing camera (SIA-7C; SIA, Duluth, GA) or negatives, which were subsequently scanned and digitized (SprintScan 45i; Polaroid, Waltham, MA). In Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc, San Jose, CA), the brightness and contrast were adjusted to optimize the images. Dorsal views of the distributions of tectopulvinar cells were generated in Neurolucida three-dimensional reconstruction software. The final figure (see Fig. 20) was subsequently composed in PowerPoint software.

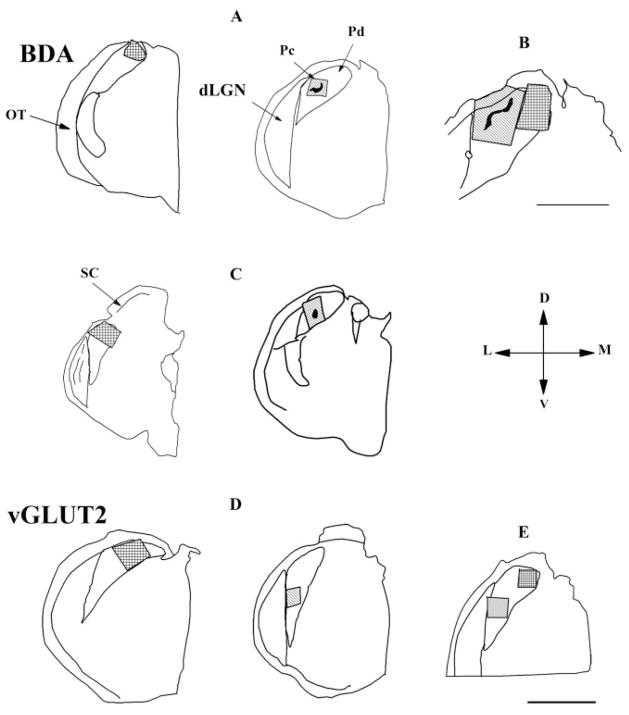

Fig. 20.

A: Tectopulvinar cells that project to the Pd are located in the medial SC, and tectopulvinar cells that project to the Pc are located in the lateral SC. The distributions of SC cells labeled by retrograde transport from three Pd injections are schematically illustrated in a dorsal view of the left SC. Case 1 corresponds to case 9-04-1AB (illustrated in Fig. 5A); case 2 corresponds to case 5-06-6AB (illustrated in Fig. 4C); case 3 corresponds to case 8-06-1D-left (illustrated in Fig. 5B). The distributions of SC cells labeled by retrograde transport from two Pc injections are schematically illustrated in a dorsal view of the right SC. Case 4 corresponds to case 8-06-1D-right (illustrated in Fig. 4A); case 5 corresponds to case 10-04-1AB (illustrated in Fig. 4B). The orientation of the SC is shown on the right SC, and the topography of SC receptive fields is shown on the left SC (with lines indicating the horizontal and vertical meridians, as described by Lane et al., 1971). The diagrams (B,C) schematically illustrate two possible arrangements of tectopulvinar projections that could account for the results of the anterograde and retrograde tracing experiments and the possible functions of the tectal pathways through the Pd and Pc subdivisions of the pulvinar nucleus. B: Each tectopulvinar cell might project topographically to the pulvinar nucleus (medial SC to Pd and lateral SC to Pc) and additionally issue a nontopographic collateral projection to the Pd. C: One population of tectopulvinar cells might project topographically to the pulvinar nucleus (medial SC to Pd and lateral SC to Pc), and an addition population of tectopulvinar cells (which we failed to label with our techniques) might project in a nontopographic manner to the Pd. Diffuse projections may mediate an escape response via projections to the amygdala, whereas the topographic projections may mediate pursuit responses via cortical and striatal projections. See text for details.

RESULTS

Distribution and morphology of tectopulvinar cells

Figures 1 and 2 show photographs of BDA injection sites in the pulvinar nucleus and the morphology of SC cells labeled by retrograde transport. As previously reported (Albano et al., 1979; Graham and Casagrande, 1980), most tectopulvinar cells are located in the lower SGS and SO and extend widespread dendrites into the upper SGS. Cells located in the upper SGS, which have more restricted dendritic arbors, were associated with injections that missed the pulvinar nucleus and involved the adjacent dLGN.

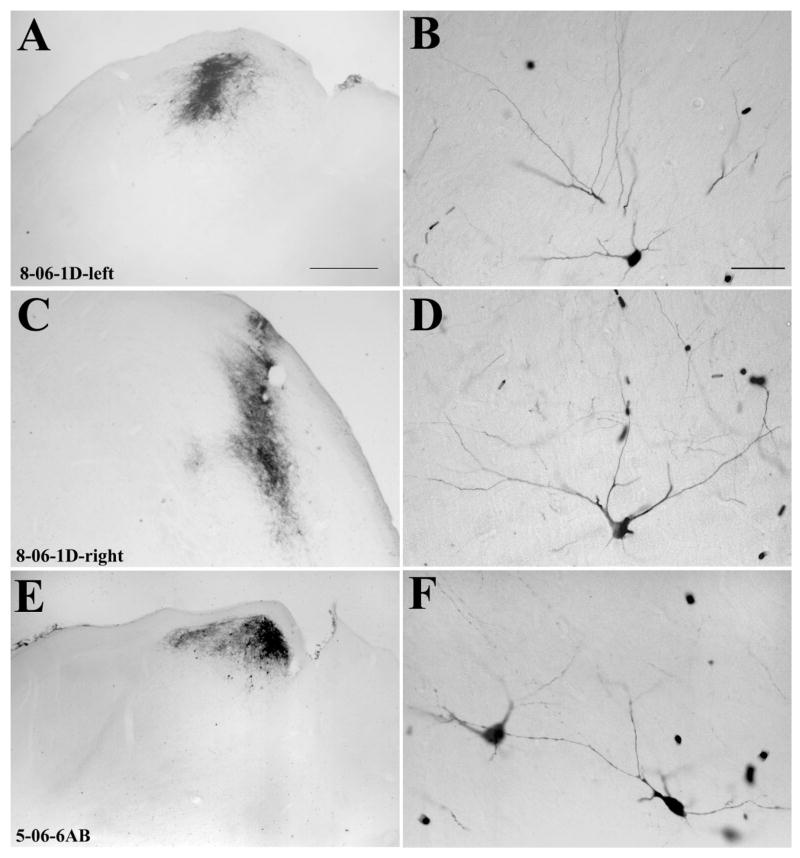

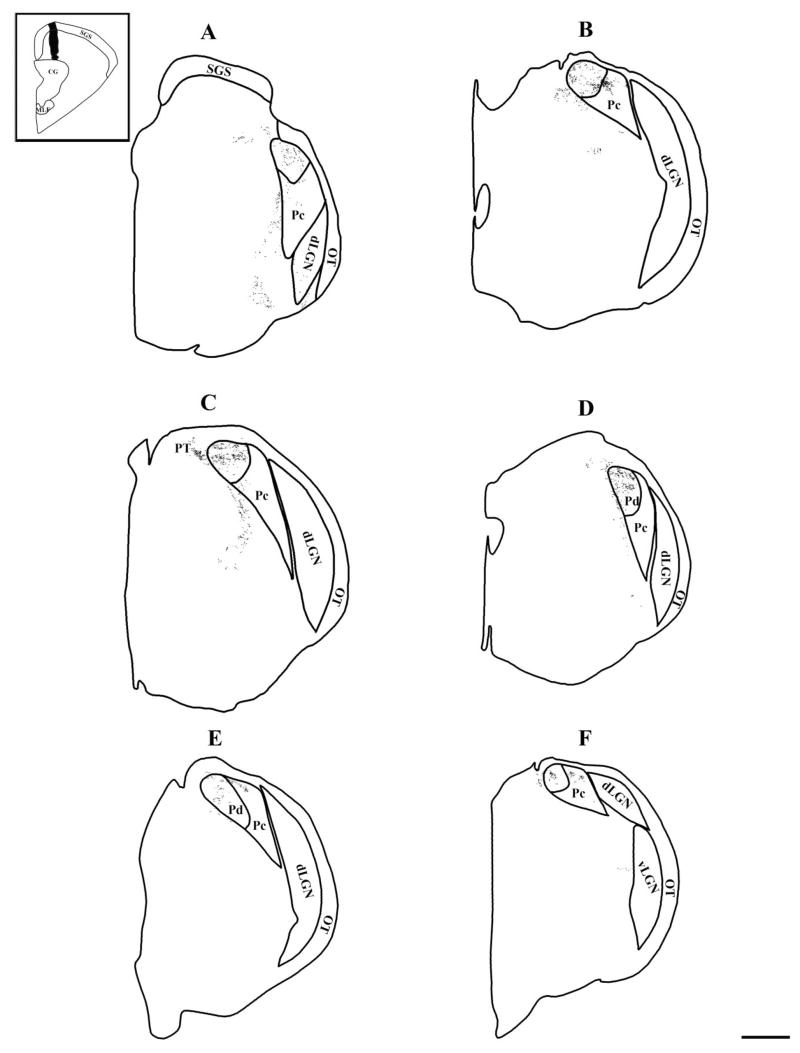

Fig. 1.

Injections of BDA label tectopulvinar cells by retrograde transport, located in the lower SGS and SO, which extend widespread dendrites into the upper SGS. Three different injection sites are illustrated (A,C,E), and each is paired with an example of tectopulvinar cells labeled by the injection (B,D,F). Injections that fill the pulvinar nucleus (A) label cells throughout the SC (B; distribution plotted in Fig. 3A). Injections confined to the Pd (C) or Pc (E) label fewer cells (distributions plotted in Figs. 4, 5). Most tectopulvinar cells in which the BDA fills the dendrites display widespread arbors. Scale bars = 500 μm in A (applies to A,C,E); 100 μm in B (applies to B,D,F).

Fig. 2.

Injections of BDA label tectopulvinar cells by retrograde transport, located in the lower SGS and SO. Three different injection sites are illustrated (A,C,E), and each is paired with an example of tectopulvinar cells labeled by the injection (B,D,F). Injections confined to the Pd (A,E) or Pc (C) label a small number of cells (distributions plotted in Figs. 4, 5), which extend widespread dendrites into the upper SGS. Scale bars = 500 μm in A (applies to A,C,E); 50 μm in B (applies to B,D,F).

Figures 3–6 are plots of the distribution of SC cells labeled by the tracer injections in the pulvinar nucleus. All labeled cells were located ipsilateral to the injection sites. After large injections (4-05-5), tectopulvinar cells were located throughout the rostrocaudal and mediolateral extent of the SC. After smaller injections, tectopulvinar cells were distributed within more restricted regions of the SC. In general, injections in the rostral/medial pulvinar labeled cells in the medial SC (9-04-1AB, 8-06-1D-left, 5-06-6AB-left, 11-05-1AB-left), whereas injections in the caudal/lateral pulvinar labeled cells in the more lateral SC (10-04-1AB, 8-06-1D-right, 11-05-1AB-right).

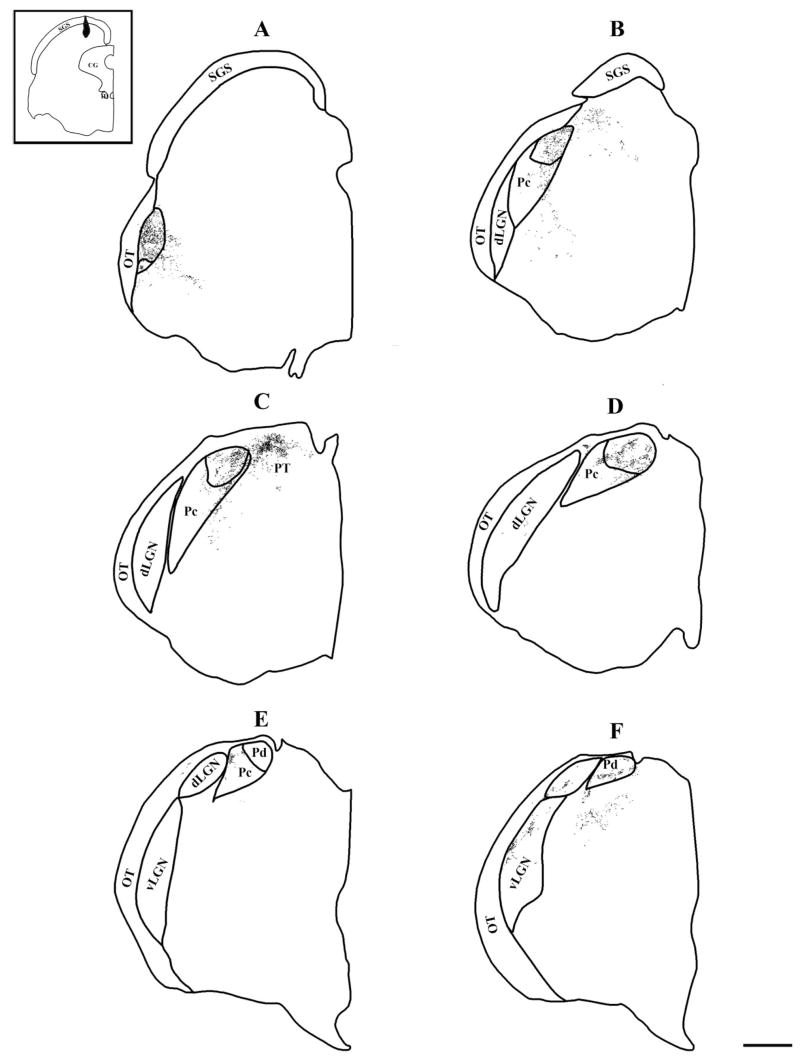

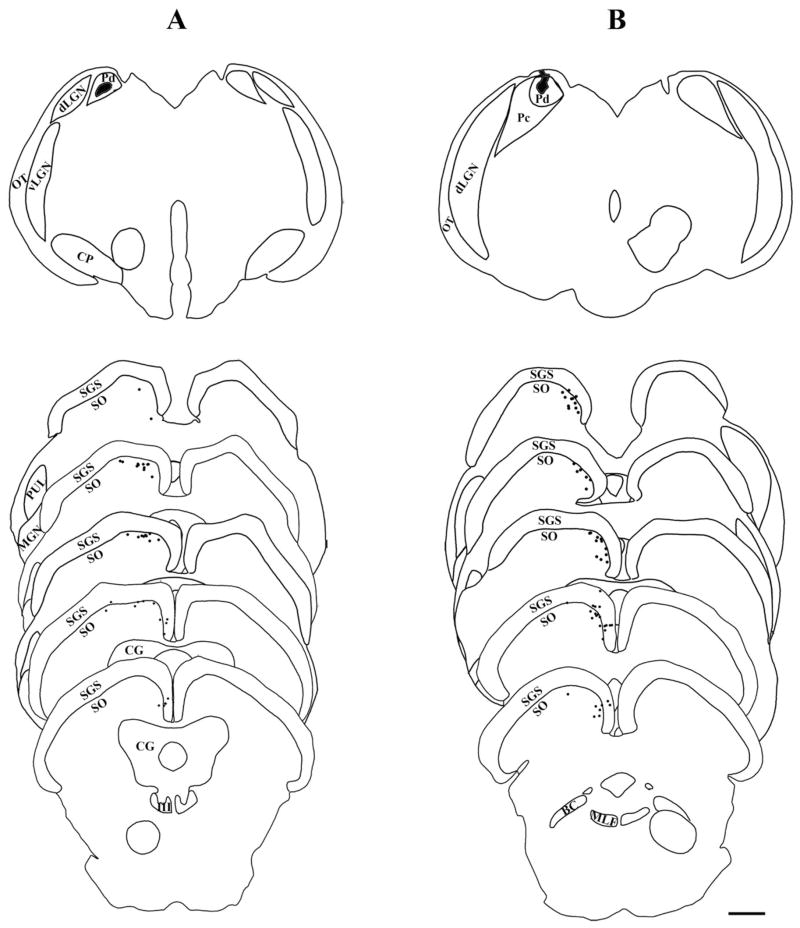

Fig. 3.

Tectopulvinar cells labeled by the retrograde transport of BDA are distributed within the lower SGS and upper SO. Injection sites in the pulvinar nucleus are depicted in black, and each labeled cell is indicated by a black dot. The SC sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). The borders of the Pd and Pc subdivisions of the pulvinar nucleus were determined in adjacent sections stained for AChE. Large injections (A, case 4-05-4) labeled cells throughout the superior colliculus (SC). Injections that included the Pd and Pc (B, case 1-02-1AB) labeled cells throughout the central regions of the SC. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Fig. 6.

Tectopulvinar cells labeled by the retrograde transport of FG are distributed within the lower SGS and upper SO. Injection sites in the pulvinar nucleus are depicted in black, and each labeled cell is indicated by a black dot. The SC sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). The borders of the Pd and Pc subdivisions of the pulvinar nucleus were determined in adjacent sections stained for AChE. Injections that included both the Pd and the Pc (A, case 5-06-5AB) labeled cells throughout the central regions of the SC. Injections that primarily involved the Pd (B, case 11-05-1AB-left) labeled cells in the medial SC. Injections that primarily involved the Pc (C, case 11-05-1AB-right) labeled cells in the lateral SC. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Labeled cells shifted toward the middle of the mediolateral dimension of the SC when injection sites included the more central regions of the pulvinar nucleus (5-06-5AB, 1-02-1AB). To determine whether tectopulvinar cells are GABAergic, we stained sections that contained FG-labeled tectopulvinar cells (5-06-5AB) with an antibody against GAD. As shown in Figure 7, although the dorsal SGS contains many GABAergic cells and terminals, the density of GABAergic fibers is much lower in the ventral SGS and SO, where tectopulvinar cells are located. These layers contain few GABAergic cells, and no double-labeled tectopulvinar cells were observed.

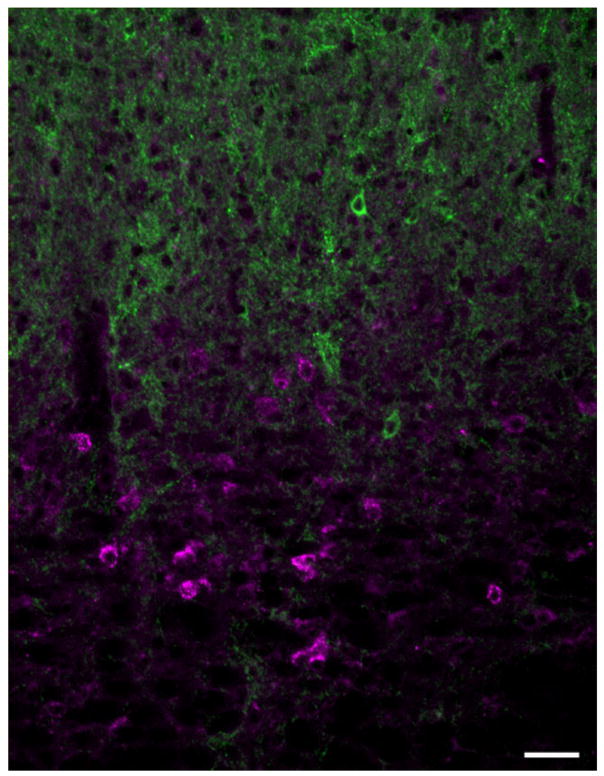

Fig. 7.

The confocal image illustrates tectopulvinar cells (labeled with FG, pseudocolored purple) and immunocytochemical staining for GAD (tagged with fluoroscein, green). No fluorogold-labeled tectopulvinar cells stained for GAD. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Distribution and morphology of tectopulvinar terminals

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of terminals in the pulvinar nucleus labeled by anterograde transport following a large pressure injection of BDA in the SC. Two distinct labeling patterns were observed, which resemble the distribution of tectopulvinar terminals labeled by the transport of wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to horse-radish peroxidase (Luppino et al., 1988). Diffusely distributed terminals filled the dorsal/medial regions of the pulvinar nucleus, whereas concentrated patches of terminals were located in the more caudal/lateral regions of the pulvinar. The large BDA injections also labeled cells in the pretectum (PT; Fig. 8A), ventral lateral geniculate nucleus (vLGN), and parabigeminal nucleus via retrograde transport (Benevento and Fallon, 1978; Kawamura et al., 1978; Jiang et al., 1996; Baldauf et al., 2003).

Fig. 8.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections stained to reveal the distribution of tectopulvinar terminals labeled via a pressure injection of BDA in the SC (A,C) and adjacent sections stained for AChE (B,D). In the dorsomedial regions of the pulvinar nucleus, terminals are diffusely distributed (outlined by black dotted lines in A,C). The region of diffuse terminals (indicated by white dotted lines in B,D) corresponds to the Pd subdivision of the pulvinar nucleus, which stains darkly with the AChE reaction (Lyon et al., 2003). Dense clusters of terminals are located in the Pc subdivision of the pulvinar nucleus, which stains lightly with the AChE reaction. Scale bar = 250 μm.

Lyon et al. (2003) recently described a dorsal subdivision of the pulvinar nucleus (Pd), which is characterized by dense staining for AChE; a large central subdivision (Pc), which stains moderately for AChE and cytochrome oxidase; and a ventral subdivision (Pv), which stains densely with the Cat-301 antibody. As illustrated in Figure 8, the diffusely distributed terminals were located in regions that stain densely for AChE, whereas the dense patches of terminals were mostly located in regions with light AChE activity. Thus, as suggested by Lyon et al., the Pd and Pc appear to correspond to the diffuse and specific tectorecipient zones (Luppino et al., 1988), respectively.

Figure 9 illustrates the different arrangements of tectopulvinar terminals in the Pc (Fig. 9A) and Pd (Fig. 9B), which were easily distinguished following large SC injections. Diffuse and clustered patterns of tectopulvinar terminals were not as easily distinguished following smaller inotophoretic injections in the SC (Figs. 10, 11), although the density of terminals varied. Some terminals formed more concentrated patches, whereas other terminals were more sparsely distributed. However, these patterns were not consistently matched to the pattern of AChE staining that characterizes the Pd and Pc. Confirming the retrograde tracing data, most terminals labeled after small injections in the medial SC were distributed in the Pd (compare Figs. 5, 10, and 11).

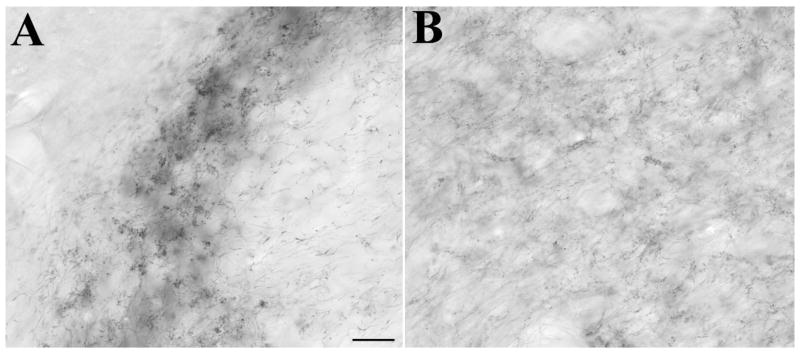

Fig. 9.

Light micrographs illustrate the two patterns of tectopulvinar terminals labeled by anterograde transport from large injections of BDA in the superior colliculus. Dense clusters of terminals (A) and diffuse terminals (B). Scale bar = 30 μm.

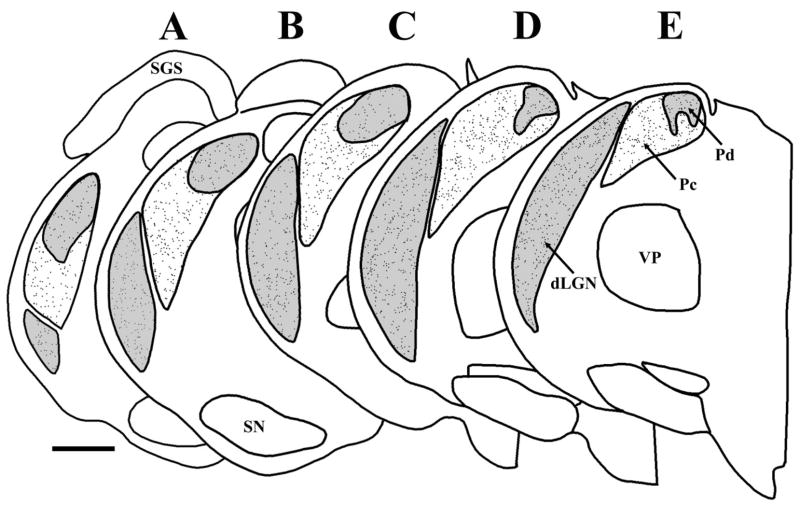

Fig. 10.

The distribution of terminals labeled by an iontophoretic injection of BDA in the rostral, medial SC is plotted. The injection site is shown in black in the inset, and the terminals are shown as small dots. The thalamus sections are arranged from caudal to rostral (A–F). The borders of the Pd and Pc were determined in adjacent sections stained for AChE. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Fig. 11.

The distribution of terminals labeled by an iontophoretic injection of BDA in the caudal, medial SC is plotted. The injection site is shown in black in the inset, and the terminals are shown as small dots. The thalamus sections are arranged from caudal to rostral (A–F). The borders of the Pd and Pc were determined in adjacent sections stained for AChE. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Fig. 5.

Tectopulvinar cells labeled by the retrograde transport of BDA are distributed within the lower SGS and upper SO. Injection sites in the pulvinar nucleus are depicted in black, and each labeled cell is indicated by a black dot. The SC sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). The borders of the Pd and Pc subdivisions of the pulvinar nucleus were determined in adjacent sections stained for AChE. Injections confined to the Pd (A, case 9-04-1AB; B, case 8-06-1D-left) labeled cells in the medial SC. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Distribution of vGLUT and GAD in the pulvinar nucleus

We examined the Pd and Pc subdivisions using antibodies against vGLUT1 and vGLUT2 (Fig. 12), which in the rat stain glutamatergic terminals of cortical and subcortical origin, respectively (Fujiyama et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001). We found that vGLUT2 staining is denser in the Pd zone than in the Pc. In contrast, vGLUT1 staining is denser in the Pc than in the Pd. This suggests that the ratio of tectal to cortical inputs is higher in the Pd than in the Pc. We also found that the patterns of vGLUT2-stained terminals in the Pd and Pc were distinct. The Pd contained elongated clusters of vGLUT2-stained terminals that appeared to surround long segments of unstained dendrites (Fig. 13C), whereas the Pc contained smaller clusters of vGLUT2-stained terminals that appeared to surround smaller dendritic segments (Fig. 13D). Although the staining intensity differed, the pattern of vGLUT1 staining was similar in the Pd (Fig. 13A) and Pc (Fig. 13B).

Fig. 12.

Immunocytochemical staining of vGLUT1 (left) and vGLUT2 (right) as revealed in adjacent sections. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Fig. 13.

Immunocytochemical staining of vGLUT1 (A,B) and vGLUT2 (C,D) in the Pd (A,C) and Pc (B,D). Scale bar = 30 μm.

We also examined the Pd and Pc in sections stained for GAD. Figure 14 is a plot of the distribution of GAD-stained cells in the tree shrew pulvinar and dLGN. In the Pd, the average density of GAD-stained neurons was 112.79 ± 42.39 cells/mm2, whereas, in the Pc, the average density was 128.43 ± 30.46 cells/mm2. This difference in interneuron density was not found to be significant (t-test, P > 0.8).

Fig. 14.

A–E: Distributions of cells in the Pd, Pc, and dLGN labeled with an antibody against GAD. The borders of the Pd and Pc were determined using adjacent sections stained for AChE. Sections are arranged from caudal (left, A) to rostral (right, E). Scale = 1 mm.

Synaptic targets of diffuse BDA-labeled tectopulvinar terminals

We examined the synaptic targets of a total of 255 labeled tectopulvinar terminals that were primarily distributed in a diffuse manner (101 from case 9-00-6UT; 101 from case 12-01-1; 53 from case 11-01-1AB). The locations of the blocks of tissue examined are illustrated in Figure 15. Examples of diffuse tectopulvinar terminals are illustrated in Figure 16. Diffusely distributed terminals were sampled in blocks of tissue from the Pd.

Fig. 15.

Drawings illustrate the location of Pd and Pc tissue blocks, within coronal sections of the pulvinar nucleus, which were sampled for ultrastructural analysis. Cases 9-00-6-UT (A), 12-01-1 (B), and 11-01-1AB (C) were examined to identify synaptic contacts made by BDA-labeled tectopulvinar terminals. Cases 4-00-1UT (D) and 9-00-7-UT (E) were examined to identify synaptic contacts made by vGLUT2-immunoreactive terminals. Scale bar in B = 1 mm, in E = 2 mm.

Fig. 16.

Examples of tectopulvinar terminals in the Pd labeled by the anterograde transport of BDA. Most tectopulvinar terminals contact (white arrows) non-GABAergic dendrites (identified by a low density of overlying gold particles). Adjacent non-GABAergic synapses are indicated with black arrows. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Each examined section was also stained for GABA by using postembedding immunocytochemical techniques. Pre- and postsynaptic profiles were considered to be GABAergic if the gold particle density overlying them was higher than that found overlying 95% of the small profiles with round vesicles (RS profiles) photographed within the same tissue. In all cases, most of the BDA-labeled terminals were GABA-negative (95/101 or 94.06% in case 9-00-6UT, 74/101 or 73.27% in case 12-01-1, and 53/53 or 100% in case 11-01-1AB).

As described above, tectopulvinar cells labeled by retrograde transport are non-GABAergic, and we did not observe GABAergic terminals labeled from the smaller injection SC sites. Therefore, the GABAergic terminals labeled following larger injections likely represent pretectopulvinar terminals (Baldauf et al., 2005), particularly insofar as more GABAergic terminals were labeled following injections in the most rostral SC. Therefore, we confined our analysis to the synaptic targets of non-GABAergic BDA-labeled terminals.

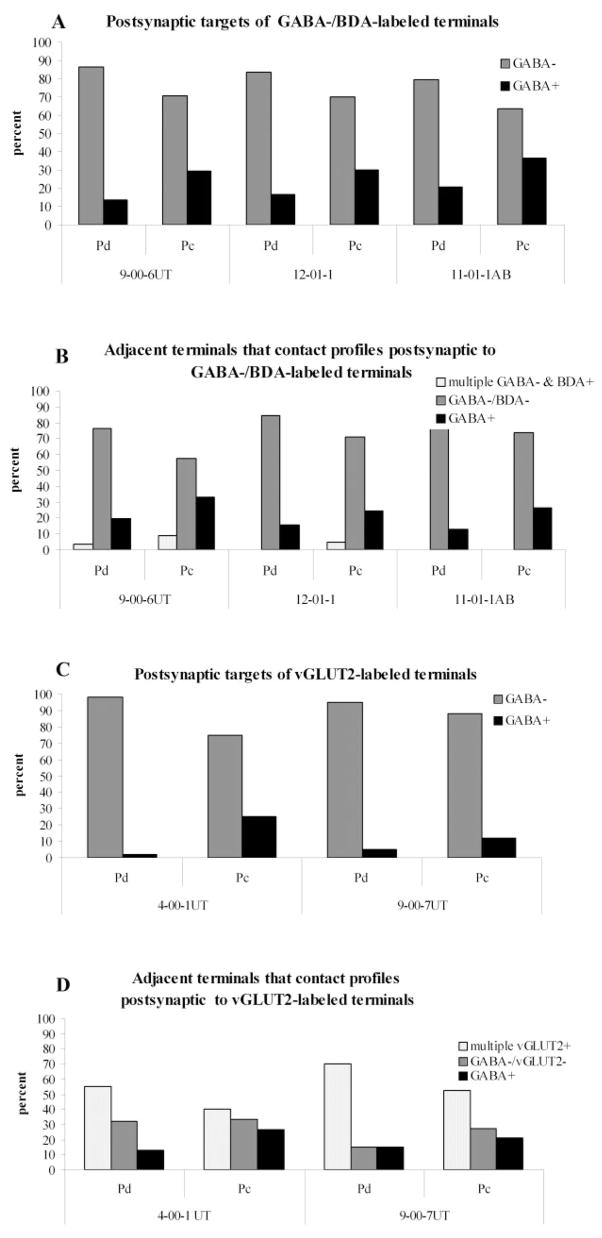

We found that most of the postsynaptic profiles contacted by non-GABAergic BDA-labeled terminals in the Pd were GABA-negative dendrites (82/95 or 86.32% in case 9-00-6UT; 62/74 or 83.78% in case 12-01-1; 42/53 or 79.25% in case 11-01-1AB; see Fig. 19). Vesicles were never observed in the GABA-negative postsynaptic dendrites. However, most profiles postsynaptic to non-GABAergic BDA-labeled terminals that were found to be GABA-positive contained vesicles (10/13 or 76.9% in case 9-00-6UT; 12/12 or 100% in case 12-01-1; 11/11 or 100% in case 11-01-1AB). This is consistent with other dorsal thalamic nuclei, in which the GABAergic interneurons form dendritic terminals (Hamos et al., 1985).

Fig. 19.

Histograms illustrate the percentage of GABAergic and non-GABAergic profiles postsynaptic to tectopulvinar terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of BDA (A) or terminals labeled using an antibody against vGLUT2 (C). A higher proportion of terminals (labeled with either method) contacted GABAergic profiles in the Pc compared with the Pd. Adjacent terminals that contact profiles postsynaptic to BDA-labeled terminals (B) or vGLUT2-labeled terminals (D) were more frequently found to be GABAergic in the Pc. Dendrites in both the Pd and the Pc were found to be contacted by multiple vGLUT2-labeled terminals.

The size (measured as the minimum diameter) of the GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to GABA-negative BDA-labeled terminals in the Pd was smaller (0.64 ± 0.23 μm) than the size of non-GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to these terminals (1.07 ± 0.67 μm). We also examined the GABA content of other terminals (adjacent to the BDA-labeled terminals) that made synaptic contacts with the tectorecipient dendrites. As shown in Figure 19, most of these adjacent terminals were GABA-negative and BDA-negative terminals (62/81 or 76.54% for case 9-00-6UT; 61/72 or 84.72% for case 12-01-1; 47/54 or 87.04% in case 11-01-1AB). Few dendrites received synaptic input from more than one BDA-labeled terminal within the same thin section.

Synaptic targets of specific BDA-labeled tectopulvinar terminals

We examined the synaptic targets of a total of 281 labeled tectopulvinar terminals that were located primarily in clusters (110 from case 9-00-6UT; 111 from case 12-01-1; 60 from case 11-01-1AB) in sections stained for GABA. The locations of the blocks examined are illustrated in Figure 15, and examples of synaptic contacts are illustrated in Figure 17. Clustered terminals were sampled in blocks of tissue from the Pc. As observed in the Pd, most BDA-labeled terminals in the Pc were non-GABAergic (103/110 or 93.64% in case 9-006UT; 97/111 or 87.39% in case 12-01-1; 60/60 or 100% in case 11-01-1AB). For the reasons provided for the Pd, we limited our analysis to the synaptic targets of non-GABAergic BDA-labeled terminals.

Fig. 17.

Examples of tectopulvinar terminals in the Pc labeled by the anterograde transport of BDA. Most tectopulvinar terminals contact (white arrows) non-GABAergic dendrites (identified by a low density of overlying gold particles, A,C–E). Occasional labeled terminals contact GABAergic dendrites (identified by a high density of overlying gold particles), most of which contain vesicles (B). Adjacent non-GABAergic synapses are indicated with single black arrows. Adjacent GABAergic synapses are indicated with double black arrows. Scale bar = 1 μm.

As illustrated in Figure 19, a higher percentage of the dendrites postsynaptic to non-GABAergic tectopulvinar terminals are GABAergic in the Pc (30/103 or 28.9% in case 9-006UT; 29/97 or 33% in case 12-01-1; 22/60 or 33.9% in case 11-01-1AB) compared with the Pd (13/91 or 14.3% in case 9-006UT; 12/75 or 16% in case 12-01-1; 11/53 or 20.81% in case 11-01-1AB). This difference was found to be statistically significant (t-test, P < 0.0002). Most of these GABAergic tectorecipient dendrites in the Pc contained vesicles (21/30 or 71.4% in case 9-006UT; 23/29 or 80% in case 12-01-1; 21/22 or 95.45% in case 11-01-1AB), similar to GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to tectal terminals in the Pd (see above). The GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to GABA-negative BDA-labeled terminals in the Pc were smaller (0.66 ± 0.25 μm) than the non-GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to those terminals (0.97 ± 0.46 μm). As illustrated in Figure 19, adjacent terminals that contact tectorecipient dendrites were found to be GABAergic more often in the Pc (22/66 or 33.33% in case 9-00-6UT; 31/127 or 24.41% in case 12-01-1; 18/68 or 26.47% in case 11-01-1AB) than in the Pd (16/81 or 19.75% in case 9-00-6UT; 11/72 or 15.28% in case 12-01-1; 7/54 or 12.96% in case 11-01-1AB).

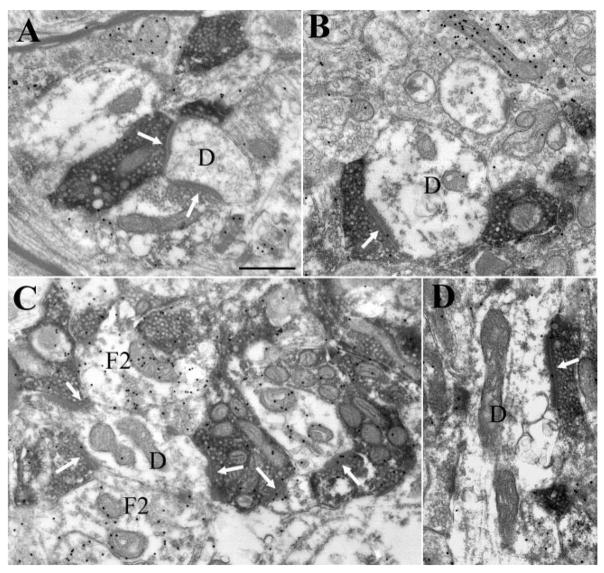

Synaptic targets of vGLUT2 terminals in the Pd

We examined the synaptic targets of a total of 206 vGLUT2-positive terminals in the Pd of 2 tree shrews (100 contacts from case 4-00-1UT and 106 contacts from case 9-00-7UT). The ultrastructure and synaptic arrangements of the vGLUT2 terminals in the Pd (Fig. 18A,B) were similar to those of diffuse tracer-labeled tectopulvinar terminals (Fig. 16). As with tectopulvinar terminals, the postsynaptic targets of the vGLUT2-positive terminals were mostly non-GABAergic dendrites (98/100 or 98% in case 4-00-1UT and 101/106 or 95.28% in case 9-00-7UT; Fig. 19), and all of the GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2-positive terminals contained vesicles (2/2 in case 4-00-1UT and 5/5 in case 9-00-7UT). The size of dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2-labeled terminals (1.22 ± 0.56 μm for nonGABAergic dendrites; 0.70 ± 0.13 μm for GABAergic dendrites) was also similar to the size of dendrites postsynaptic to BDA-labeled terminals (1.07 ± 0.67 μm for nonGABAergic dendrites; 0.64 ± 0.23 μm for GABAergic dendrites).

Fig. 18.

Examples of terminals labeled with an antibody against the type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter (vGLUT2) in the Pd (A,B) and Pc (C,D). Most vGLUT2-labeled terminals contact (white arrows) non-GABAergic dendrites (D, identified by a low density of overlying gold particles). Contacts with GABAergic profiles that contain vesicles (F2, identified by a high density of overlying gold particles) are more common in the Pc. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2-labeled terminals were also primarily contacted by other non-GABAergic terminals. However, although very few dendrites in the Pd were observed to be contacted by more than one BDA-labeled terminal in single thin sections, for dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2-labled terminals, adjacent contacts often contained vGLUT2 (17/31 or 54.84% in case 4-00-1UT and 19/27 or 70.37% in case 9-00-7UT).

Synaptic targets of vGLUT2 terminals in the Pc

We examined the synaptic targets of a total of 212 (112 contacts from 4-00-1UT and 100 contacts from 9-00-7UT) vGLUT2-labeled terminals in the Pc. The ultrastructure and synaptic arrangements of the vGLUT2 terminals in the Pc (Fig. 18C,D) were similar to those of clustered tracer-labeled tectopulvinar terminals (Fig. 17).

Most vGLUT2-labeled terminals in the Pc contacted non-GABAergic dendrites, but more GABAergic dendrites in the Pc were contacted by vGLUT2-labeled terminals (28/112 or 25% in case 4-00-1UT; 12/100 or 12% in case 9-00-7UT) than in the Pd (2/100 or 2% in case 4-00-1UT; 5/106 or 4.72% in case 9-007UT; Fig. 19). This difference was found to be statistically significant (t-test, P < 0.0001).

The size of dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2-labeled terminals in the Pc (0.93 ± 0.44 μm for non-GABAergic dendrites; 0.62 ± 0.14 μm for GABAergic dendrites) was also similar to the size of dendrites postsynaptic to BDA-labeled terminals in the Pc (0.97 ± 0.46 μm for non-GABAergic dendrites; 0.66 ± 0.25 μm for GABAergic den-drites). As in the Pd, most of the GABAergic dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2-labeled terminals contained vesicles (23/28 or 82.14% in case 4-00-1UT and 11/12 or 91.67% in case 9-00-7UT). In addition, for dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2-labled terminals, adjacent contacts often contained vGLUT2 (18/45 or 40% in case 4-00-1UT; 25/48 or 52.08% in case 9-00-7UT).

DISCUSSION

Synaptic arrangements in the Pd and Pc

Luppino et al. (1988) and Lyons et al. (2003) presented evidence that the tree shrew pulvinar nucleus is composed of several distinct zones. In the present study, we focused on the tectorecipient zones, Pd and Pc. In support of the results reported by Luppino et al, we found that, after tracer injections in the SC, diffusely organized terminals fill the Pd, whereas more terminals are located in dense patches within the Pc. We found that, at the ultrastructural level, tectopulvinar terminals contact mostly non-GABAergic dendrites. However, tectopulvinar terminals contacted a higher percentage of GABAergic profiles within the Pc than within the Pd. These results indicate that tectopulvinar terminals contribute to distinct circuits within each zone. Our examination of tissue stained with the vGLUT2 antibody also indicated that the synaptic organizations of the Pd and Pc are distinct. Terminals that contain vGLUT2, likely to be of tectal origin, contact more GABAergic profiles in the Pc than in the Pd.

In comparison with tectopulvinar terminals, our preliminary studies show that the synaptic targets of corticopulvinar terminals are similar in the Pd and Pc (Chomsung et al., 2007). In both regions, inputs from the temporal cortex are small terminals that innervate small-caliber dendrites. Thus, in both the Pd and the Pc, cortical terminals likely are located distal to tectal terminals on the dendritic arbors of pulvinar neurons. Other projections to the Pd and Pc have not been examined at the ultrastructural level, and differences in density or distribution within the Pd and Pc have not been noted. For example, cholinergic projections are relatively sparse in both the Pd and the Pc in comparison with other visual thalamic nuclei, such as the dLGN and lateral nucleus (Fitzpatrick et al., 1988).

Topography and convergence of tectopulvinar projections

The ultrastructure of tectopulvinar terminals was first described using degeneration techniques in the gray squirrel (Robson and Hall, 1977). These terminals were described as medium-sized terminals (RM profiles) that surrounded dendritic shafts.

Only a few terminals in any cluster surrounding a dendrite degenerated after the SC lesions, so it was suggested that the clusters permit convergence of tectal terminals and/or terminals from other unidentified sources onto the same dendritic segment (Robson and Hall, 1977). We attempted to determine whether tectal terminals converge in the Pd or Pc by comparing the synaptic targets of vGLUT2-stained terminals to terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of BDA. In both the Pd and the Pc, it was rare to observe multiple BDA-labeled terminals contacting single dendrites (within single sections). However, in vGLUT2-stained tissue, single dendritic segments contacted by multiple vGLUT2-stained terminals were more commonly observed. If vGLUT2 is confined to tectal terminals, this suggests that in both the Pd and the Pc multiple tectal terminals converge on single cells.

Luppino et al. (1988) observed that tectopulvinar terminals were labeled throughout the diffuse zone regardless of the location of the SC injection site, whereas terminals in the specific zone changed location in correspondence with changes in the SC injection site. Thus, it was proposed that the diffuse tectopulvinar projection (to Pd) converges in a nontopographic manner, whereas the clusters of specific tectopulvinar terminals (to Pc) are topographically organized. We therefore expected that injections confined to the Pd would label cells throughout the SC, whereas injections confined to the Pc would label cells in restricted regions of the SC.

However, with the exception of our largest pulvinar injections, all of our small pulvinar injections labeled cells in restricted regions of the SC, and the number of labeled cells appeared to be related more to the size of the injection site than to its placement in the Pd or Pc. Furthermore, we consistently found that injections within the Pd labeled cells in more medial regions of the SC, whereas injections in the Pc labeled cells in more lateral regions of the SC (summarized in Fig. 20A). In addition, our smaller SC injections, which were placed in the medial SC, labeled terminals that were distributed primarily in the Pd. Thus, although large SC injections revealed distinct distributions of tectopulvinar terminals identical to the diffuse and specific terminals observed by Luppino et al., the results of our retrograde tracing experiments suggest that the SC projects topographically to the both Pd and Pc, potentially forming one visuotopic map of the upper (Pd) to lower (Pc) visual field.

Detailed studies by Marín et al. (2003) of the projections from the pigeon optic tectum to the nucleus rotundus have revealed a complex interdigitating pattern of tectorotundal projections. In their study, small tracer injections in the nucleus rotundus labeled cells throughout the optic tectum, suggesting convergence. However, small adjacent injections of two different tracers in the nucleus rotundus did not result in double-labeled tectal cells. These results suggest that axons of individual tectorotundal cells terminate in multiple discrete arbors that are widely distributed and that the arbors contributed by neighboring cells interdigitate without extensive overlap.

This interdigitating pattern is unlikely to explain our results in the tree shrew, in that all of our small pulvinar injections labeled cells in restricted rather than widespread regions of the SC, and even relatively large SC injections labeled terminals in limited regions of the Pc. The results from the tree shrew are more similar to those in other mammals. For example, there is evidence for a topographic organization of the projections from the SC to the pulvinar nucleus of the primate (Partlow et al., 1977; Lin and Kaas, 1979) and the LP nucleus of the cat (Abramson and Chalupa, 1988).

Figure 20 schematically illustrates possible arrangements of tectopulvinar axon arbors that might explain the results of our anterograde and retrograde tracing studies. As illustrated in Figure 20B, tectopulvinar cells could project topographically to both the Pc and the Pd, where they terminate in discrete dense clusters, but each tectopulvinar axon might also contribute diffuse collaterals that terminate in the Pd. Tectopulvinar cells might be labeled by retrograde transport only via uptake from the dense clusters, so that small, discrete pulvinar injections label tectopulvinar cells only in restricted regions of the SC.

Alternatively (Fig. 20C), diffuse convergent inputs to the Pd might arise from a separate population of tectopulvinar cells that we failed to label by retrograde transport. If either of these arrangements is correct, discrete spatially organized patches in the Pd would be labeled only after the most medial SC injections, and these might be obscured by overlapping diffuse projections. In fact, when we placed small tracer injections in the medial SC, we found that tectopulvinar terminals were most densely distributed within the Pd, and it was difficult to distinguish diffuse and clustered terminals. For ultra-structural analysis of the terminals labeled by the small medial injections, our tissue blocks taken from the Pd and Pc contained terminals that appeared to be distributed primarily in diffuse or clustered arrangements, respectively. However, distinctive terminal arrangements were less evident than in the cases in which larger injections were placed in the SC. Although this might simply be due to distinct projection patterns being more difficult to detect when fewer axons are labeled, it is possible that overlapping diffuse and specific projections in the Pd obscure the clusters of terminals. The overlap of the diffuse and specific projections might also explain the greater intensity of vGLUT2 staining in the Pd in comparison with the Pc. More sensitive retrograde tracers may help to resolve this issue, although single-axon reconstructions will likely be required to characterize the organization of tectopulvinar terminal arborizations completely.

Morphology of tectopulvinar cells

The tectopulvinar cells labeled by retrograde transport were sufficiently filled to identify them as wide-field vertical cells, as previously described (Albano et al., 1979; Graham and Casagrande, 1980). However, the filling was not sufficient to determine whether more than one type of wide-field vertical cell was labeled. In the ground squirrel, two types of wide-field vertical cells have been distinguished in experiments that utilized in vitro intracellular injections of cells in slices of the SC (Major et al., 2000). These studies revealed dendritic specializations, referred to as bottlebrush endings, at the distal ends of wide-field vertical cells. These endings were distributed either in the most dorsal regions of the SGS (SGS1; type I cells) or more ventrally in SGS2 (type II cells). The cells also varied in their laminar distribution, with type I cells located within the SGS3 and type II cells located at ventral border of SGS3 and dorsal SO.

Similar cell types reside in the avian optic tectum and project to different subdivisions of the nucleus rotundus (Karten et al., 1997; Luksch et al., 2001). In mammals, the more limited dendritic filling in retrograde transport studies has made it difficult to establish whether type I and type II wide-field vertical cells have different projection targets. However, in the cat, cells that project to the LPm and LPl-2 are located in the lower SGS, whereas cells that project to the ventral LP are located in the SO (Abramson and Chalupa, 1988).

We examined tecto-LP projections in the cat (Kelly et al., 2003) and found that, in the LPm (which like the Pd stains densely for AChE; Lyon et al., 2003), tectal terminals primarily surround non-GABAergic dendritic shafts. In contrast, in the LPl-2 (an AChE-light zone), tectal terminals formed more glomerular-like arrangements and contacted more GABAergic dendritic profiles. These distinctions are similar to those we observed between the Pd and the Pc in tree shrew.

In the primate, at least two zones of the pulvinar nucleus receive tectal input (Lin and Kaas, 1979; Stepniewska et al., 2000). The central and posterior divisions of the inferior pulvinar (PIc and PIp) receive dense projections from the SC, and both appear to arise from a single band of cells located in the lower SGS and SO (Huerta and Harting, 1982). Similarly, we saw no obvious differences in the laminar distribution of cells that give rise to the projections to the tree shrew Pd and Pc. However, because few cells were labeled following injections clearly confined to the Pd or Pc, our observations were limited to a small sample of cells. Previous studies of the tree shrew have found a single band of SC cells labeled following injections that included both the Pd and the Pc (Albano et al., 1979; Graham and Casagrande, 1980). However, a preliminary study by Carey (1987) found that, compared with the AChE-light zones of the tree shrew pulvinar nucleus, the AChE-rich zones received input from larger cells located deeper in the SC. Again, single-axon reconstructions will likely be required to resolve whether the projections from the SC to the Pd and Pc originate from distinct cell types.

Functional implications

Major et al. (2000) proposed (later modeled by Luksch et al., 2001, 2004), that wide-field vertical cells serve as efficient motion detectors that are activated by the sequential activation of topographic retinal and/or cortical inputs to their extensive dendritic arbors. If this proposal is correct, the primary signal relayed to both the Pd and the Pc may encode the motion of visual targets. From the findings of our retrograde tracing studies, the Pd should be activated by motion in the upper visual field (represented in the medial SC), and the Pc should be activated by motion in the lower visual field (represented in the lateral SC; Lane et al., 1971). Simultaneous movement in the upper and lower visual fields may further amplify the activity in the Pd by summing the contributions of diffuse projections.

Studies in the rat have indicated that there are multiple output channels from the SC that initiate motor responses to sensory stimuli (Dean et al., 1989). Stimulation of the medial SC initiates defensive or escape behavior in response to threatening or looming signals. In contrast, stimulation of the more lateral regions of the SC initiates pursuit behavior. The efferent projections of the Pd and Pc suggest that these regions also may serve distinct functions in initiating motor responses to visual signals. For example, the Pd projects to the amygdala, striatum, and caudal/ventral temporal cortex, whereas the Pc projects to the striatum and rostral/dorsal temporal cortex (Luppino et al., 1988; Chomsung et al., 2006, 2007). Luppino et al. (1988) previously suggested that the ventral temporal cortex may provide a link between sensory and limbic regions, and the unique projection of the Pd to the amygdala further suggests that the tectopulvinar pathway may mediate rapid responses to visual stimuli moving across the upper visual field, and/or movements that activate both upper and lower visual fields, either of which might be considered threatening.

A number of fMRI studies in humans show that observation of fearful faces increases activity in the SC, pulvinar nucleus, and amygdala (Morris et al., 2001; Vuilleumier et al., 2003; Liddell et al., 2005; Ward et al., 2005). It has further been suggested that these structures mediate short-latency reactions to threatening stimuli by direct projections from the SC to the pulvinar and from the pulvinar nucleus to the amygdala. Recent studies also indicate that lesions of the human pulvinar nucleus lead to a deficit in the detection of fearful facial expressions (Ward et al., 2007). In contrast, topographic projections from the lateral SC to the Pc may coordinate visuomotor signals during the detection and capture of insects or fruit located in the lower visual field. As reviewed by McHaffie et al. (2005), the pulvinar is part of a subcortical loop connecting the basal ganglia and the SC. Topographic visual signals relayed from the SC to the pulvinar nucleus may be subsequently relayed to the striatum and temporal cortex to direct orienting/pursuit movements. The larger number of GABAergic terminals associated with tectopulvinar terminals in the Pc may contribute to the relay of signals that more precisely convey the location of visual targets and/or the timing of their movements.

Fig. 4.

Tectopulvinar cells labeled by the retrograde transport of BDA are distributed within the lower SGS and upper SO. Injection sites in the pulvinar nucleus are depicted in black, and each labeled cell is indicated by a black dot. The SC sections are arranged from rostral (top) to caudal (bottom). The borders of the Pd and Pc subdivisions of the pulvinar nucleus were determined in adjacent sections stained for AChE. Injections confined to the Pc (A, case 8-06-1D-right; B, case 10-04-1AB) labeled cells in the lateral SC, and injections confined to the Pd (C, case 5-06-6AB) labeled cells in the lateral SC. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Arkadiusz Slusarczyk, Mr. Michael Eisenback, and Ms. Cathie Caple for their expert assistance with histology and electron microscopy. We also thank Dr. David Fitzpatrick, Dr. Thomas Norton, and Mr. Kent Udy for generously contributing many of the tree shrews used in this study.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: NS35377; Grant sponsor: Sigma Xi.

Abbreviations

- BC

brachium conjunctivum

- CG

central gray

- CP

cerebral peduncle

- dLGN

dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus

- Ha

habenula

- Li

lateral intermediate nucleus

- MGN

medial geniculate nucleus

- MLF

medial longitudinal fasiculus

- OT

optic tract

- Pd

dorsal pulvinar nucleus

- Pc

central pulvinar nucleus

- PT

pretectum

- PUL

pulvinar nucleus

- Pv

ventral pulvinar nucleus

- Pyr

pyramidal tract

- SC

superior colliculus

- SGS

stratum griseum superficiale

- SO

stratum opticum

- SN

substantia nigra

- vLGN

ventral lateral geniculate nucleus

- VP

ventroposterior nucleus

- III

oculomotor nucleus

LITERATURE CITED

- Abramson BP, Chalupa LM. Multiple pathways from the superior colliculus to the extrageniculate visual thalamus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1988;271:397– 418. doi: 10.1002/cne.902710308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albano JE, Norton TT, Hall WC. Laminar origin of projections from the superficial layers of the superior colliculus in the tree shrew, Tupaia glis. Brain Res. 1979;173:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf ZB, Wang XP, Wang S, Bickford ME. Pretectotectal pathway: an ultrastructural quantitative analysis in cats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:141–158. doi: 10.1002/cne.10792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf ZB, Wang S, Chomsung RD, May PJ, Bickford ME. Ultra-structural analysis of projections to the pulvinar nucleus of the cat. II: pretectum. J Comp Neurol. 2005;485:108–126. doi: 10.1002/cne.20487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benevento LA, Fallon JH. The ascending projections of the superior collicullus in rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) J Comp Neurol. 1975;160:339–360. doi: 10.1002/cne.901600306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickford ME, Carden WB, Patel NC. Two types of interneurons in the cat visual thalamus are distinguished by morphology, synaptic connections, and nitric oxide synthase content. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:83–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RG. Tree shrew pulvinar nucleus: differential projections to AChE-rich and -poor zones from superior colliculus base on cell sizes, depth and morphology. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1987;13:1436. [Google Scholar]

- Chalupa LM, Abramson BP. Visual receptive fields in the striate-recipient zone of the lateral posterior-pulvinar complex. J Neurosci. 1989;9:347–357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-01-00347.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Petry HM, Eisenback MA, Bickford ME. Synaptic organization of pulvinar efferent projections in the tree shrew. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2006;32:241.1. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. Synaptic organization of projections from the temporal cortex to the tree shrew pulvinar nucleus. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2007;33:392.10. [Google Scholar]

- Dankowski A, Bickford ME. Inhibitory circuitry involving Y cells and Y retinal terminals in the C laminae of the cat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:368–379. doi: 10.1002/cne.10640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datskovskaia A, Carden WB, Bickford ME. Y retinal terminals contact interneurons in the cat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2001;430:85–100. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010129)430:1<85::aid-cne1016>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Biasi S, Frassoni C, Spreafico R. GABA immunoreactivity in the thalamic reticular nucleus of the rat. A light and electron microscopic study. Brain Res. 1986;399:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Redgrave P, Westby GW. Event or emergency? Two response system in the mammalian superior colliculus. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D, Penny GR, Schmechel DE. Glutamic acid decarboxylase immunoreactive neurons and terminals in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1809–1829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01809.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D, Conley M, Luppino C, Matelli M, Diamond IT. Cholinergic projections from the midbrain reticular formation and the parabigeminal nucleus to the lateral geniculate nucleus in the tree shrew. J Comp Neurol. 1988;272:43– 67. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyama F, Furuta T, Kaneko T. Immunocytochemical localization of candidates for vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:379–387. doi: 10.1002/cne.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneser-Jensen FA, Blackstad JW. Distribution of acetylcholinesterase in the hippocampal region of the guinea pig. I. Entorhinal area, subiculum and presubiculum. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1971;114:460– 481. doi: 10.1007/BF00325634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Casagrande VA. A light microscopic and electron microscopic study of the superficial layers of the superior colliculus of the tree shrew (Tupaia glis) J Comp Neurol. 1980;191:133–151. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamos JE, Van Horn SC, Raczkowski D, Uhlrich DJ, Sherman SM. Synaptic connectivity of a local circuit neuron in lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. Nature. 1985;317:618– 621. doi: 10.1038/317618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR, Vaughn JE, Barber RP, Roberts E. GABA neurons are the major cell type of nucleus reticularis thalami. Brain Res. 1980;200:341–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MF, Harting JK. Sublamination within the superficial gray layer of the squirrel monkey: an analysis of the tectopulvinar projection using anterograde and retrograde transport methods. Brain Res. 1983;261:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZD, King AJ, Moore DR. Topographic organization of projection from the parabigeminal nucleus to the superior colliculus in the ferret revealed with fluorescent latex microspheres. Brain Res. 1996;743:217–232. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Fujiyama F. Complementary distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters in the central nervous system. Neurosci Res. 2002;42:243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten HJ, Cox K, Mpodozis J. Two distinct populations of tectal neurons have unique connections within the retinotectorotundal pathway of the pigeon (Columba livia) J Comp Neurol. 1997;387:449– 465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura S, Fukushima N, Hattori S, Tashiro T. A ventral lateral geniculate nucleus projection to the dorsal thalamus and the midbrain in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1978;31:95–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00235807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly LR, Li J, Carden WB, Bickford ME. Ultrastructure and synaptic targets of tectothalamic terminals in the cat lateral posterior nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:472– 486. doi: 10.1002/cne.10800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RH, Allman JM, Kaas JH. Representation of the visual field in the superior colliculus of the grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) and the tree shrew (Tupaia glis) Brain Res. 1971;26:277–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang S, Bickford ME. Comparison of the ultrastructure of cortical and retinal terminals in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate and lateral posterior nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:394– 409. doi: 10.1002/cne.10646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell BJ, Brown KJ, Kemp AH, Barton MJ, Das P, Peduto A, Gordon E, Williams LM. A direct brainstem-amygdala-cortical “alarm” system for subliminal signals of fear. Neuroimage. 2005;24:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CS, Kaas JH. The inferior pulvinar complex in owl monkeys’ architectonic subdivisions and patterns of input from the superior colliculus and subdivisions of visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1979;187:655–678. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luksch H, Karten HJ, Kleinfeld D, Wessel R. Chattering and differential signal processing in identified motion-sensitive neurons of parallel visual pathways in the chick tectum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6440–6446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06440.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luksch H, Khanbabaic R, Wessel R. Synaptic dynamics mediate sensitivity to motion independent of stimulus details. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:380–388. doi: 10.1038/nn1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppino G, Matelli M, Carey RG, Fitzpatrick D, Diamond IT. New view of the organization of the pulvinar nucleus in Tupaia as revealed by tectopulvinar and pulvinar-cortical projections. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273:67– 86. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon DC, Jain N, Kaas JH. The visual pulvinar in tree shrews I. Multiple subdivisions revealed through acetylcholinesterase and Cat-301 chemoarchitecture. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:593– 606. doi: 10.1002/cne.10939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major DE, Luksch H, Karten HJ. Bottlebrush dendritic endings and large dendritic fields: motion-detecting neurons in the mammalian tectum. J Comp Neurol. 2000;423:243–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Letelier JC, Henny P, Sentis E, Farfán G, Fredes F, Pohl N, Karten H, Mpodozis J. Spatial organization of the pigeon tectorotundal pathway: an interdigitating topographic arrangement. J Comp Neurol. 2003;458:361–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.10591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJ. The mammalian superior colliculus: laminar structure and connections. Prog Brain Res. 2006;151:321–378. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)51011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHaffie JG, Stanford TR, Stein BE, Coizet V, Redgrave P. Subcortical loops through the basal ganglia. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:401– 407. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melone M, Burette A, Weinberg RJ. Light microscopic identification and immunocytochemical characterization of glutamatergic synapses in brain sections. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:495–509. doi: 10.1002/cne.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana V, Yingchun N, Sunjara V, Hua X, Parpura V. Vesicular glutamate transporter-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2633–2642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3770-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero VM, Singer W. Ultrastructure and synaptic relations of neural elements containing glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in the perigeniculate nucleus of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1984;56:115–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00237447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero VM, Singer W. Ultrastructural identification of somata and neural processes immunoreactive to antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1985;59:151–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00237675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, DeGelder B, Weiskrantz L, Dolan RJ. Differential extra-geniculostriate and amygdala responses to presentation of emotional faces in a cortically blind field. Brain. 2001;124:1241–1252. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.6.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahmani M, Erisir A. VGluT2 immunochemistry identifies thalamocortical terminals in layer 4 of adult and developing visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;484:458– 473. doi: 10.1002/cne.20505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel WH, Graybiel AM, Mugnaini E, Elde RP, Schmechel DE, Kopin IJ. Coexistence of glutamic acid decarboxylase- and somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in neurons of the feline nucleus reticularis thalami in the cat. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1322–1332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-06-01322.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partlow GD, Colonnier M, Szabo J. Thalamic projections of the superior colliculus in the rhesus monkey, Macaca mulatta: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1977;72:285–318. doi: 10.1002/cne.901710302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NC, Bickford ME. Synaptic targets of cholinergic terminals in the pulvinar nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;387:266–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raczkowski D, Fitzpatrick D. Terminal arbors of individual, physiologically identified geniculocortical axons in the tree shrew’s striate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:500–514. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinvik E, Ottersen OP. Demonstration of GABA and glutamate in the nucleus reticularis thalami: a postembedding immunogold labeling investigation in the cat and baboon. In: Bentivoglio M, Spreafico R, editors. Cellular thalamic mechanisms. New York: Elsevier; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rinvik E, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Gamma-aminobutyrate-like immunoreactivity in the thalamus of the cat. Neuroscience. 1987;21:781–805. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson JA, Hall WC. The organization of the pulvinar in the grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). II. Synaptic organization and comparison with the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1977;173:389– 416. doi: 10.1002/cne.901730211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman MS. Functional organization of the W-, Y-, and X-cell pathways: a review and hypothesis. In: Sprague JM, Epstein AN, editors. Progress in psychobiology and physiological psychology. New York: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 233–314. [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska I, Ql HX, Kaas JH. Projections of the superior colliculus to subdivisions of the inferior pulvinar in new world and old world monkeys. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:529–549. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800174048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Armony JL, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Distinct spatial frequency sensitivities for processing faces and emotional expressions. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:624– 631. doi: 10.1038/nn1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Eisenback M, Bickford ME. Relative distribution of synapses of the pulvinar nucleus of the cat: implications regarding the “driver/modulator” theory of thalamic function. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454:482– 494. doi: 10.1002/cne.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R, Danziger S, Bamford S. Response to visual threat following damage to the pulvinar. Curr Biol. 2005;15:571–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R, Calder AJ, Parker M, Arend I. Emotion recognition following human pulvinar damage. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:1973–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]