Abstract

There is evidence that the right hemisphere is involved in processing self-related stimuli. Previous brain imaging research has found a network of right-lateralized brain regions that preferentially respond to seeing one's own face rather than a familiar other. Given that the self is an abstract multimodal concept, we tested whether these brain regions would also discriminate the sound of one's own voice compared to a friend's voice. Participants were shown photographs of their own face and friend's face, and also listened to recordings of their own voice and a friend's voice during fMRI scanning. Consistent with previous studies, seeing one's own face activated regions in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), inferior parietal lobe and inferior occipital cortex in the right hemisphere. In addition, listening to one's voice also showed increased activity in the right IFG. These data suggest that the right IFG is concerned with processing self-related stimuli across multiple sensory modalities and that it may contribute to an abstract self-representation.

Keywords: self, self-recognition, fMRI, face, voice

The concept of the ‘self ’ is highly prominent in philosophical and social psychological discourse. Recently, cognitive neuroscientists have begun to explore the neural basis of self-representation or how the brain gives rise to the self. Much of this work has focused on recognition of the self-face, the most obvious embodied representation of the self. A growing body of neuroimaging literature points towards selective activation of a right fronto-parietal network during tasks of self-recognition or self-other discrimination (Sugiura et al., 2005; Uddin et al., 2005a; Platek et al., 2006; Devue et al., 2007). Other forms of self-recognition, such as recognition of one's own voice, have received relatively less attention. In one positron emission tomography (PET) study of voice recognition, hearing the self-voice activated right inferior frontal sulcus and right parainsular cortex (Nakamura et al., 2001). An important question remains unresolved regarding the degree of abstraction of self-representation mechanisms in the brain. It is unknown whether there is an overlap in neural structures supporting representation of various aspects of the self across different sensory modalities, such as visual and auditory. Are there regions that support multimodal representations of the self, much like the regions involved in various other types of multimodal cognitive processes?

Indeed, there are several studies demonstrating that some areas in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and ventral premotor cortex are active not only for one's own body and action representations, but also for the sounds and visual aspects associated with that body part. For example, areas in the premotor cortex that are most active for the representation of hand actions are also most active for observation of hand actions (Gallese et al., 1996; Iacoboni et al., 1999; Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2006) as well as the sounds of hand actions (Kohler et al., 2002; Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2004; Kaplan and Iacoboni, 2007). This is also true for the mouth (Gazzola et al., 2006). By converging information from different modalities onto a single representation, it has been postulated that these multimodal ‘mirror’ areas are important for abstract representation (Kohler et al., 2002). Thus by bringing in together multimodal information from one's own face and voice, it could be that these areas in the IFG are also important for abstract representation of the self.

Here we used event-related fMRI to test whether such multimodal self-representation exists in the brain. We scanned participants while they viewed four types of stimuli: the self-face, a familiar-other face, the self-voice and a familiar-other voice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Twelve right-handed subjects (six males, six females, mean age 26.6 ± 4) were recruited and compensated for their participation. Subjects gave informed consent according to the guidelines of the UCLA Institutional Review Board. All participants were screened to rule out medication use, head trauma, and history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, substance abuse or other serious medical conditions.

Stimuli and task

Stimuli were individually tailored to each subject. Each subject was asked to bring someone they see on a daily basis, of the same race and gender. This person served as the ‘familiar control’ for each subject. The face stimuli were static color images constructed from pictures of the subjects’ own face and the face of a gender-matched highly familiar other acquired on a Kodak 3400C digital camera. We took four pictures of the face of each subject and each subjects’ friend. Subjects were asked to choose their own familiar control, a personal friend or colleague they encounter on a daily or almost daily basis. Images were edited using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 to remove external features (hair, ears) and create a uniform gray background.

Voices were recorded through a Shure AXS-3 microphone and digitized at 44.1 kHz. Each subject was recorded speaking the following four neutral sentences: ‘The weather is cloudy’, ‘The door is open’, ‘The lights are on’ and ‘The keys are in the bag’. Due to conduction through the bones of the head, one's own voice often sounds different on a recording than it does when heard naturally (Tonndorf, 1972). It has been shown that the effect of bone conductance is in part to accentuate low-frequency aspects of the voice (Maurer and Landis, 1990). To make the voice of one's self sound more natural, we applied an equalization filter to each recording that increased frequencies below 1000 Hz by 2 dB and decreased frequencies above 1000 Hz by 2 dB. This kind of filtering leads people to rate a recording of their own voice as sounding more like themselves (Shuster and Durrant, 2003). We then removed any DC offset and normalized each of the recordings to have the same peak volume of 0 dB.

The software package presentation (Neurobehavioral Systems Inc., Albany, CA, http://www.neuro-bs.com/) was used to present stimuli and record responses. Face stimuli were presented through magnet-compatible goggles (Resonance Technology Inc., Los Angeles, CA) and responses were recorded using two buttons of an MRI compatible response pad. During each 5 min, 12 s functional run, we presented both faces and voices of self and other. In each functional scan, subjects saw 16 pictures of their own face, 16 pictures of their familiar friend's face, 16 recordings of their own voice and 16 recordings of their familiar friend's voice. The stimuli were presented in a randomized order that was optimized to provide temporal jitter and maximize blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal discrimination between the four stimulus categories (Dale, 1999). Pictures and voices were presented for 2 s each, and there was at least a 1 second gap between stimuli. Subjects pressed a button with their right index finger if the image or voice was ‘self’ and another button with their right middle finger if the image or voice was ‘other’.

Image acquisition

Images were acquired using a Siemens Allegra 3.0 T MRI scanner. Two sets of high-resolution anatomical images were acquired for registration purposes. We acquired an magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MP-RAGE) structural volume (TR = 2300, TE = 2.93, flip angle = 8°) with 160 sagittal slices, each 1 mm thick with 0.5 mm gap and 1.33 mm × 1.33 mm in-plane resolution. We also acquired a T2-weighted coplanar volume (TR = 5000, TE = 33, flip angle = 90°) with 36 transverse slices covering the whole brain, each 3 mm thick with 1 mm gap, a 128 × 128 matrix and an in-plane resolution of 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm.

Each functional run involved the acquisition of 155 EPI volumes (gradient-echo, TR = 2000, TE = 25, flip angle = 90°), each with 36 transverse slices, 3 mm thick, 1 mm gap and a 64 × 64 matrix yielding an in-plane resolution of 3 mm × 3 mm. A functional run lasted 5 min and 12 s, and each subject completed four functional runs.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Analysis was carried out using FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool) Version 5.1, part of FSL (FMRIB's Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). After motion correction, images were temporally high-pass filtered with a cutoff period of 75 s and smoothed using a 8 mm Gaussian FWHM algorithm in 3D. The BOLD response was modeled using a separate explanatory variable (EV) for each of the four stimulus types (self-face, other-face, self-voice, other-voice). For each stimulus type, the presentation design was convolved with a gamma function to produce an expected BOLD response. The temporal derivative of this timecourse was also included in the model for each EV. Data were then fitted to the model using FSL's implementation of the general linear model.

Each subject's statistical data was then warped into a standard space based on the MNI-152 atlas. We used FLIRT (FMRIB's Linear Image Registration Tool) to register the functional data to the atlas space in three stages. First, functional images were aligned with the high-resolution coplanar T2-weighted image using 6 degrees of freedom rigid-body warping procedure. Next, the coplanar volume was registered to the T1-weighted MP-RAGE using 6 degrees of freedom rigid-body warp. Finally, the MP-RAGE was registered to the standard MNI atlas with 12 degrees of freedom affine transformation.

Mixed effects higher-level analysis was carried out using FLAME (FMRIB's Local Analysis of Mixed Effects) (Behrens et al., 2003). For our whole-brain analysis, statistical images were thresholded using clusters determined by Z > 2.3 and a corrected cluster size significance threshold of P = 0.05 (Worsley et al., 1992; Friston et al., 1994; Forman et al., 1995). Since our goal was to examine the multimodal responses within regions previously shown to be sensitive to self faces, we did a region of interest (ROI) analysis on the three brain areas we found to discriminate self from other in our previous study (Uddin, 2005a). The three ROIs that showed significantly greater signal changes for self faces compared with familiar faces in our previous study were in the right inferior frontal cortex, the right inferior parietal lobe and the right inferior occipital gyrus. Restricting our analysis to only those significant voxels from the previous study, we accepted voxels from the current study if they also reached P < 0.05 in the present study. We also calculated percent signal change for each stimulus type within these three ROIs.

RESULTS

Behavioral data

All participants were able to identify their own face and their own voice with high accuracy. Mean accuracy was 99% for face stimuli and 94% for voice stimuli. Mean response time for picture stimuli was 770 ms with a standard error of 37 ms. Mean response time for vocal stimuli was 1740 ms with a 72 ms standard error. A paired sample t-test confirmed that response time for the vocal condition were significantly slower, P < 0.001.

Imaging data

Pictures and voices vs rest

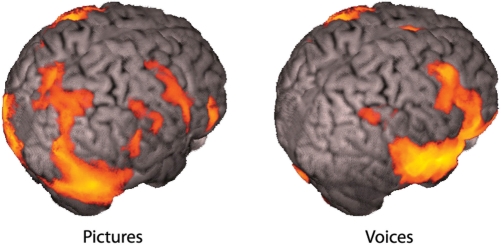

Looking at the pictures of faces produced robust activations throughout the brain, including much of the occipital lobe, parietal cortex and frontal cortex. Listening to the voices produced large activations throughout the temporal lobes and frontal lobes, as well as the cerebellum. These activations are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Viewing pictures and hearing voices compared with resting baseline.

Pictures: Self minus other

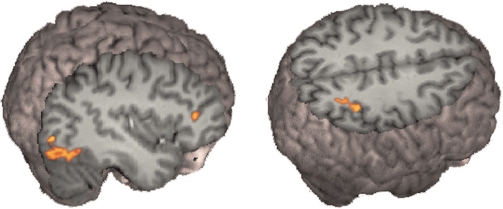

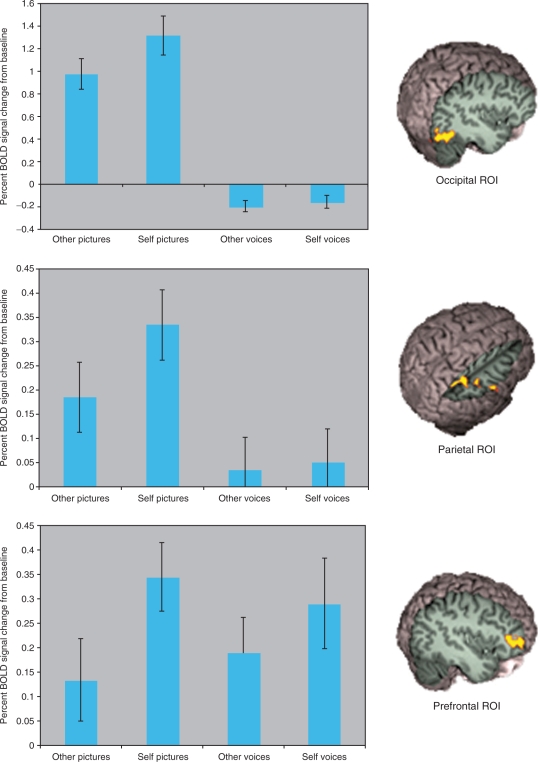

Whole-brain analysis revealed greater signal changes in the occipital lobe bilaterally, and in the inferior parietal lobe on the right side for viewing self faces compared with viewing a familiar other face. Replicating our previous result, our ROI analysis found significantly greater signal for self faces compared with a familiar other in all three ROI from our previous paper. These results are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

Faces, self minus other. Seeing one's own face produced greater signal compared with viewing a friend's face in the IFG, the inferior parietal lobe and the inferior occipital gyrus on the right side.

Fig. 3.

Voices, self minus other. Hearing one's own voice compared with a friend's voice produced greater signal in the right IFG.

Pictures: other minus self

Whole-brain analysis showed significantly greater signal in the superior temporal sulcus, the superior temporal gyrus and the inferior temporal gyrus bilaterally.

Voices: self minus other

Whole-brain analysis did not reveal any significant signal changes for this analysis. However, ROI analysis showed that hearing one's own voice compared with the voice of a familiar other led to significantly greater signal changes in the anterior part of the IFG. This is shown in Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

Signal changes in the three ROI.

Voices: other minus self

Whole-brain analysis did not reveal any significant signal changes for this analysis.

Peak coordinates for ROI analyses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Peak voxels from the ROI analysis

| Region | Hemisphere | x | y | z | Z-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-other pictures | |||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 44 | 36 | 12 | 3.2 |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | R | 36 | −82 | −8 | 3.9 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | R | 36 | −44 | 48 | 3.5 |

| Self-other voices | |||||

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 44 | 38 | 2 | 2.3 |

DISCUSSION

We replicated our previous result that viewing one's own face leads to greater signal changes in a fronto-parietal network including the IFG, the inferior occipital gyrus and the inferior parietal lobe (Uddin et al., 2005a). In addition, the right IFG also showed greater signal change when hearing one's own voice compared to hearing a friend's voice. Thus the preference for self-related stimuli in the right IFG is not restricted to visual stimuli. This result is consistent with the theory that right prefrontal cortex supports an abstract self representation.

An advantage of right hemisphere for self-recognition is fairly well supported in the literature. Behavioral studies have found a left-hand response time advantage for self-face discriminations (Keenan et al., 1999; Platek et al., 2004). In addition, Keenan et al. (2001) showed patients their own face morphed into a famous face while undergoing the Wada test, and found a bias towards reporting self faces when the left hemisphere had been anesthetized. Theoret et al. (2004) used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) over motor cortex to produce motor evoked potentials in the hand while subjects saw masked pictures of themselves or others. Seeing one's own face led to increased motor cortex excitability in the right hemisphere. Another TMS study using self-descriptive adjectives as stimuli showed greater right hemisphere motor facilitation (Molnar-Szakacs et al., 2005), and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the right inferior parietal lobule can disrupt self-face recognition (Uddin et al., 2006). However, both hemispheres of a split-brain patient are able to recognize their own face (Uddin et al., 2005b).

Neuroimaging studies of self-recognition are also generally consistent with our data. Devue et al. (2007) found activations in right IFG and the right insula when participants viewed their own face compared with a gender-matched colleague. Interestingly, they did not find a difference in activity in the IFG for viewing one's own body. It may be that the body shape is not as prominent a cue for self concept as one's face or voice. Sugiura et al. (2005) found greater activations for self faces in the right frontal operculum, right temporal-occipital-parietal junction and in the left fusiform gyrus. In a subsequent study, Sugiura et al. (2006) showed self-preferential activity in the network including the right IFG not only for faces but also for moving body parts, although self-related activity was greater for faces. They argue that the right inferior frontal cortex supports an amodal, conceptual self representation.

In the only other neuroimaging study known to us in which self voices were directly compared to familiar voices, Nakamura et al. (2001) used PET to study voice recognition and found self-preferential activity in the inferior frontal sulcus and parainsular cortex on the right side. The coordinates of the peak activation in that study (42, 44, 2) are within a centimeter of the peak found in the present study (44, 38, 2).

There have been few studies to directly compare self discriminations across sensory modalities. Platek et al. (2004) found that smelling one's own odor facilitated the visual identification of one's own face, as did hearing one's own name. This cross-modal priming effect suggests a convergence in the brain for stimuli identified as self. Our data show that this convergence may occur in the right inferior frontal cortex.

It is possible that the other self-sensitive brain regions may also prefer self in the auditory modality but we did not have the statistical power to find it. However, we did not see any sub-threshold activation for self in our other two a-priori ROIs, and they were not activated above baseline by hearing voices in general. Self-related activity for faces was much more robust and widespread than it was for voices. Differences in the pattern of activation for the two sensory modalities may be related to differences in the difficulty of the identification task. While classification of stimuli was highly accurate with both visual and auditory stimuli, response time to auditory stimuli were significantly longer. This may indicate that the voice task was more difficult or may be related to the fact that while a face can be recognized instantaneously, a voice stimulus unfolds over time. In addition, while we did filter the stimuli to increase lower frequencies and make it more naturalistic, there are still likely to be differences between the way one sounds on a recording and the way one hears their own voice when speaking.

It is notable that the inferior frontal lobe has also been implicated in cross-modal representations of actions (Pizzamiglio et al., 2005; Gazzola et al., 2006; Kaplan and Iacoboni, 2007). As others have pointed out (Sugiura et al., 2006), the brain mechanisms responsible for tracking contingencies between motor plans and their various sensory consequences would be well-positioned to identify sounds and sights that are habitually self-produced. Indeed, the inferior frontal lobe is known to be part of the mirror neuron system, which is believed to play a role in mapping observed others onto the self (Iacoboni et al., 1999; Gallese, 2003; Rizzolatti and Craighero, 2004). We have suggested that if these neurons are sensitive to similarity between an observed agent and the self, then they will be most active when the agent observed is one's own self (Uddin et al., 2005a, Uddin et al., 2007; Iacoboni, 2008).

Our present data confirm the hypothesis that the fronto-parietal mirror neurons system is sensitive to the visual presentation of one's own face, and find a specific cross-modal preference for self in the right IFG. Sensorimotor systems that respond across sensory modalities may form the basis for abstract concepts (Gallese and Lakoff, 2005). We suggest that the right IFG may be crucial for an abstract conceptual representation of self.

REFERENCES

- Aziz-Zadeh L, Iacoboni M, Zaidel E, Wilson S, Mazziotta J. Left hemisphere motor facilitation in response to manual action sounds. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19(9):2609–12. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz-Zadeh L, Wilson SM, Rizzolatti G, Iacoboni M. Congruent embodied representations for visually presented actions and linguistic phrases describing actions. Current Biology. 2006;16(18):1818–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens T, Woolrich MW, Smith S. Multi-subject null hypothesis testing using a fully bayesian framework: theory. Ninth Int. Conf. on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM. Human Brain Mapping, 8. 1999. Optimal experimental design for event-related fMRI; pp. 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devue C, Collette F, Balteau E, et al. Here I am: the cortical correlates of visual self-recognition. Brain Research. 2007;1143:169–82. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SD, Cohen JD, Fitzgerald M, Eddy WF, Mintun MA, Noll DC. Magnetic Resonance Medicine, 33. 1995. Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fmri): Use of a cluster-size threshold; pp. 636–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Worsley KJ, Frakowiak RSJ, Mazziotta JC, Evans AC. Human Brain Mapping, 1. 1994. Assessing the significance of focal activations using their spatial extent; pp. 214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V. The roots of empathy: the shared manifold hypothesis and the neural basis of intersubjectivity. Psychopathology. 2003;36(4):171–80. doi: 10.1159/000072786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Rizzolatti G. Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 2):593–609. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V, Lakoff G. The brain's concepts: The role of the sensory-motor system in conceptual knowledge. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2005;22(3–4):455–79. doi: 10.1080/02643290442000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzola V, Aziz-Zadeh L, Keysers C. Empathy and the somatotopic auditory mirror system in humans. Current Biology. 2006;16(18):1824–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Woods RP, Brass M, Bekkering H, Mazziotta JC, Rizzolatti G. Cortical mechanisms of human imitation. Science. 1999;286(5449):2526–8. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M. Mirroring People. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JT, Iacoboni M. Multimodal action representation in human left ventral premotor cortex. Cognitive Processing. 2007;8(2):103–13. doi: 10.1007/s10339-007-0165-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan JP, McCutcheon B, Freund S, Gallup GG, Jr, Sanders G, Pascual-Leone A. Left hand advantage in a self-face recognition task. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37(12):1421–5. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan JP, Nelson A, O’Connor M, Pascual-Leone A. Self-recognition and the right hemisphere. Nature. 2001;409(6818):305. doi: 10.1038/35053167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler E, Keysers C, Umilta MA, Fogassi L, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G. Hearing sounds, understanding actions: action representation in mirror neurons. Science. 2002;297(5582):846–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1070311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer D, Landis T. Role of bone conduction in the self-perception of speech. Folia Phoniatrica. 1990;42:226–9. doi: 10.1159/000266070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar-Szakacs I, Uddin LQ, Iacoboni M. Right-hemisphere motor facilitation by self-descriptive personality-trait words. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;21(7):2000–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kawashima R, Sugiura M, et al. Neural substrates for recognition of familiar voices: a pet study. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39(10):1047–54. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzamiglio L, Aprile T, Spitoni G, et al. Separate neural systems for processing action- or non-action-related sounds. Neuroimage. 2005;24(3):852–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platek SM, Loughead JW, Gur RC, et al. Neural substrates for functionally discriminating self-face from personally familiar faces. Human Brain Mapping. 2006;27(2):91–8. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platek SM, Thomson JW, Gallup GG., Jr Cross-modal self-recognition: the role of visual, auditory, and olfactory primes. Conscious and Cognition. 2004;13(1):197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Craighero L. The mirror-neuron system. Annual Reviews in Neuroscience. 2004;27:169–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster LI, Durrant JD. Toward a better understanding of the perception of self-produced speech. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2003;36(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(02)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M, Sassa Y, Jeong H, et al. Multiple brain networks for visual self-recognition with different sensitivity for motion and body part. Neuroimage. 2006;32(4):1905–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M, Watanabe J, Maeda Y, Matsue Y, Fukuda H, Kawashima R. Cortical mechanisms of visual self-recognition. Neuroimage. 2005;24(1):143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoret H, Kobayashi M, Merabet L, Wagner T, Tormos JM, Pascual-Leone A. Modulation of right motor cortex excitability without awareness following presentation of masked self-images. Cognitive Brain Research. 2004;20(1):54–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonndorf J. Bone conduction. In: Tobias JV, editor. Foundations of Modern Auditory Theory. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1972. pp. 197–237. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Iacoboni M, Lange C, Keenan JP. The self and social cognition: the role of cortical midline structures and mirror neurons. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11(4):153–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Molnar-Szakacs I, Zaidel E, Iacoboni M. rTMS to the right inferior parietal lobule disrupts self-other discrimination. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2006;1(1):65–71. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Kaplan JT, Molnar-Szakacs I, Zaidel E, Iacoboni M. Self-face recognition activates a frontoparietal ‘mirror’ network in the right hemisphere: an event-related fmri study. Neuroimage. 2005a;25(3):926–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Rayman J, Zaidel E. Split-brain reveals separate but equal self-recognition in the two cerebral hemispheres. Consciousness and Cognition. 2005b;14(3):633–40. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ, Evans AC, Marrett S, Neelin P. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 12. 1992. A three-dimensional statistical analysis for CBF activation studies in human brain; pp. 900–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]