Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can detect small tumors for resection but at a huge cost of health resources. The challenge is to reduce the surveillance population. We reported that 96% of HCC patients but only 24% of controls were infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) with A1762T, G1764A mutations in Guangxi, China. It is likely to be extremely beneficial in terms of cost and resources if a significant number of tumours can be detected early by screening this selected population. Our aim is to test this hypothesis.

METHODS:

A cohort of 2258 hepatitis B surface antigen positive subjects aged 30-55 was recruited in Guangxi. Following evaluation of virological parameters at baseline, HCC is diagnosed by six-monthly measurements of serum alpha fetoprotein levels and ultrasonographic examinations.

RESULTS:

61 cases of HCC were diagnosed after 36 months of follow-up. The HCC rate was higher in the mutant than wild type group (p<0.001, rate ratio (RR) 6.23 [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.83, 13.68]). The HCC rate in the male mutant group was higher than that in the male wild type group (p<0.001, RR 11.54 [95% CI 3.58, 37.24]. Specifically, 93.3% of male cases are infected with the mutant. Multivariate analyses showed that in males, increasing age and A1762T, G1764A double mutations are independently associated with developing HCC.

CONCLUSIONS:

HBV A1762T, G1764A mutations constitute a valuable biomarker to identify a subset of male HBsAg carriers aged >30 at extremely high risk of HCC in Guangxi, and likely elsewhere.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, polymerase chain reaction, nucleotide sequences, viral load, mutation

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth most common cause of cancer mortality worldwide and the third most common in men (1).The incidence of HCC is not uniform across the world but varies according to the prevalence of underlying liver diseases. The highest incidence of HCC is seen in China (2). Surgery remains the only curative modality for HCC but a large percentage of cases are not suitable for surgery because of intrahepatic or distant metastases at the time of diagnosis. However, five-year survival rates of 61.3% have been achieved for resection of small HCCs in China (3). Recent studies suggest that surveillance of HCC by regular testing for serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and/or ultrasound (US) imaging can detect HCC at an earlier and (probably) resectable stage, which may be translated into improved survival (4, 5). However, a population-based HCC surveillance program would place a huge demand on public health resources and be impractical in most countries. The challenge is how to identify the population at highest risk of HCC. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most important etiology of HCC in Asia (6). In China, individuals aged over 35 years and with serological evidence of HBV infection (positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, HBsAg) are currently considered to be the population at highest risk for HCC (5).

The mechanisms of oncogenesis of HBV remain obscure. However, attention has been focussed on viral factors associated with the development of HCC, including HBV genotype, viral load and the occurrence of specific mutations in the HBV genome. HBV can be divided into eight different genotypes (designated by capital letters A to H) based on an intergroup divergence of 8% or more in the complete nucleotide sequence (7, 8). HBV genotypes vary in their geographic distribution and have been reported to have clinical relevance (9). Genotypes B and C are predominant in Asia (10) but their precise significance in terms of development of HCC remains controversial (10-13). Several studies have shown that high viral loads, specifically, titres of viral DNA in serum above 104-5 genome copies/ml, are associated with the development of HCC (10, 14, 15). The common precore mutation (G1896A), mutations in enhancer II (C1653T) and the basal core promoter (T1753V and the double mutations, A1762T, G1764A), and deletions in the pre-S region (13, 14, 16) have been reported to be associated with the development of HCC. Perhaps the most convincing association is with HBV with double mutations in the basal core promoter (BCP) (17-21).

In our initial study (17), we found BCP double mutations in HBV DNA from serum and/or tumour tissue of 13 of 14 HCC patients but only 3 of 11 asymptomatic controls. In a follow-up study (18), 35 of 36 HCC patients, but only 9 of 39 asymptomatic carriers, were found to be infected with HBV with BCP double mutations. Overall, we found the mutations in HBV from 96% of HCC patients, but only 24% of controls, from Guangxi, China.

As mentioned above, the key to achieve cost-effectiveness for screening is to identify the population at highest risk and currently, in Guangxi, China, it is practical to consider HBsAg positive males aged >30 as the population at highest risk (22-24). Our previous studies suggest that only around one quarter of them are infected with HBV variants with double mutations in the BCP. (18)Therefore, it is likely to be extremely beneficial in terms of cost and resources if a significant number of tumours can be detected early by screening this selected population.

We hypothesize that, in Southern China and perhaps elsewhere in the world, BCP double mutations constitute a valuable biomarker for screening carriers of HBsAg in order to identify the subset at highest risk of developing HCC. To test this hypothesis, we have embarked on a prospective study of HBsAg-positive adults living in Long An county, Guangxi, one of the regions of China with the highest annual incidence of HCC (25). Here, we report the results of 36 months of follow-up.

STUDY SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study population

Study subjects were recruited from agricultural workers aged 30-55 living in the rural area of Long An county, Guangxi, China. Informed consent in writing was obtained from each individual. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Guangxi Institutional Review Board and the UCL Committee on the Ethics of Non-NHS Human Research (Project number 0042/001).

Our Chinese study team comprises doctors from the Centres for Disease Prevention and Control (CPDC) of Long An county and the CPDC of Guangxi Province. Individuals aged 30 to 55 years resident in 128 villages throughout Long An county were selected for testing for HBsAg using stratified sampling. In brief, the entire county was divided into 128 strata according to village and 25% of individuals aged 30 to 55 were selected randomly from each stratum. From 1st March, 2004, the study teams travelled to 128 villages in each of the 12 townships of Long An county to visit and inform agricultural workers aged 30-55 and take a 3 ml sample of blood by venepuncture for screening. All samples were tested for HBsAg and those positive were tested in China for AFP to exclude pre-existing HCC and for HBV DNA using nested PCR. We also detected anti-HCV and excluded those positive to eliminate the confounding effect of HCV infection on the incidence of HCC. We started to follow up our study subjects from 1st July, 2004. Each study subject completed a one-page questionnaire at the first visit and provided a serum sample every six months for the assessment of virological parameters and AFP concentrations, and is monitored for HCC by US. All cases of HCC diagnosed were confirmed at the Medical University of Guangxi, the Cancer Institute of Guangxi or the Hospital of Guangxi (Nanning).The diagnosis was made by one or more of the following: (i) surgical biopsy; (ii) elevated serum AFP (levels ≥400 ng/ml), excluding pregnancy, genital cancer and other liver diseases including metastasis of tumors from other organs, plus clinical symptoms or one image (US or computed tomography, CT); (iii) elevated serum AFP (levels <400 ng/ml), excluding pregnancy, genital cancer and other liver diseases including metastasis of tumors from other organs, plus two images (US and CT) or one image (US or CT) and two positive HCC markers such as DCP, GGT II, AFU, CA19-9 etc.

Serological testing

Sera were tested for HBsAg, HBeAg/anti-HBe, anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) using enzyme immunoassays (Zhong Shan Biological Technology Company, Limited, Guangzhou, China). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were determined using a Reitman kit (Sichuan Mike Scientific Technology Company, Limited, Chengdu, China).

Nested PCR for HBV DNA and Nucleotide Sequencing

DNA was extracted from 85 μl serum by pronase digestion followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. First round PCR was carried out in a 50 μl reaction using primers B935 (nt 1240–1260, 5′-AACCTTTGTGGCTCCTCTG-3′) and MDC1 (nt 2304–2324, 5′-TTGATAAGATAGGGGCATTTG-3′), with 5 min hot start followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 90 sec. Second round PCR was carried out on 5 μl of the first round product in a 50 μl reaction using primers CPRF1 (nt 1678–1695, 5′-CAATGTCAACGACCGACC-3′) and CPRR1 (nt 1928–1948, 5′-GAGTAACTCCACAGTAGCTCC-3′) and 5 min hot start, then 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec.

The purpose of the nested PCR above was to derive as much nucleotide sequence data as possible from the BCP and surrounding region. However, the BCP is very close to the 5′ end of the minus strand of genomic DNA and the PCR spans that discontinuity, resulting in a detection limit of around 103-105 genomes/ml (and this is confirmed by our viral load data). Therefore, negative samples were retested using a modified nested PCR that did not span the 5′ ends of the genome. The primers were (first round) P2 (26) (nt1823-1806, 5′-CCGGAAAGCTTGAGCTCTTCAAAAAGTTGCATGGTGCTGG-3′) and XSEQ1 (nt1547-1569, 5′-CCCCGTCTGTGCCTTCTCATCTG-3′) and (second round) CPRF1 and MDN5R (nt1794-1774, 5′-ATTTATGCCTACAGCCTCCT-3′); otherwise, the parameters for PCR were as described above. To determine the sequence at nucleotide position 1653, samples were amplified using the original PCR described above but substituting primer XSEQ1 for CPRF1 in the second round.

Products from the second round were confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis and then purified using the GenElute™ PCR Clean-up Kit (SIGMA, St. Louis MO, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cycle sequencing was carried out directly on 2 μl purified amplicons DNA using primer CPRR1 (products from original PCR) or CPRF1 (products from modified PCR) and a BigDye® Terminator V3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Methods

Statistical comparisons of the prevalence of BCP double mutations between males and females and across the different age groups and the analysis of the occurrence of nucleotide 1653 and 1753 mutations in individuals with HCC and controls were performed using Chi-squared tests. Associations between pre-existing double mutations and the development of HCC were tested for significance using Poisson regression models, after adjusting for the potential confounding effects of age and sex, and with the (log) follow-up time offset, using SAS version 9.1. For these analyses, follow-up was considered from the time of entry in the study until the development of HCC or last follow-up visit, whichever occurred first. All P-values were two-tailed, and P <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Grouping of study subjects

In order to identify study subjects, 27,340 individuals in Long An county, Guangxi were tested for HBsAg; 14.5% were positive. The overall prevalence was significantly higher in males (16.7%) than females (12.6%) and declined markedly with age in both genders (Table 1). All HBsAg positive serum samples, except those that were AFP positive, were tested in China for HBV DNA using a nested PCR designed to amplify the BCP and precore region. 1596 were positive and included in the study cohort. In order to ensure sufficient samples for stratification analysis, we enrolled according to stratified sampling 1402 HBsAg positive individuals who were found HBV DNA negative in China. These samples were retested in London using a more sensitive, modified nested PCR (see Methods) to amplify the BCP whilst avoiding the gap in genomic HBV DNA. A sufficient quantity of the baseline sample remained for this analysis in 1,033 of the 1,402 cases. Only 246 samples were negative using both assays. The nucleotide sequences of the products of both sets of positive PCR reaction were determined (the sequence of 29 samples could not be determined and therefore were grouped as HBV DNA not detected): 1001 were wild type at positions 1762/1764, 1257 had the specific mutations A1762T, G1764A, and 96 had other mutations at these positions or were positive for anti-HCV. The last group included 69 with the single mutations A1762T or G1764A, 12 with other single or double mutations at these positions, and 8 with deletions of up to 9 nucleotides (Table 2).

Table 1. Frequency of HBsAg according to gender and age.

| Age | No. Subjects |

HBsAg (+) |

HBsAg (+) Rate (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| 25∼ | 126 | 131 | 257 | 30 | 19 | 49 | 23.8 | 14.5 | 19.1 |

| 30∼ | 3465 | 3505 | 6970 | 726 | 500 | 1226 | 21.0 | 14.3 | 17.6 |

| 35∼ | 2999 | 3121 | 6120 | 531 | 411 | 942 | 17.7 | 13.2 | 15.4 |

| 40∼ | 2630 | 2953 | 5583 | 423 | 375 | 798 | 16.1 | 12.7 | 14.3 |

| 45∼ | 1711 | 2164 | 3875 | 225 | 251 | 476 | 13.2 | 11.6 | 12.3 |

| 50∼ | 1961 | 2574 | 4535 | 214 | 268 | 482 | 10.9 | 10.4 | 10.6 |

| Total | 12892 | 14448 | 27340 | 2149 | 1824 | 3973 |

16.7 (16.0-17.3) |

12.6 (12.1-13.2) |

14.5 (14.1-14.9) |

Males vs. Females (HBsAg positivity rate): X2=89.737, P< 0.001

Table 2. HBV DNA and prevalence of HBV BCP double mutations according to gender.

| Gender | N | HBV DNA(+) | A1762T, G1764A mutations |

Unusual mutations at A1762, G1764 |

Prevalence of A1762T, G1764A mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1638 | 1310† | 704 | 42* | 53.7 (51.0-56.4) |

| Female | 1360 | 1044† | 560 | 47** | 53.6 (50.6-56.6) |

| Total | 2998 | 2354 † | 1264 | 89 |

53.7 (51.7-55.7) |

individuals for whom HBV DNA was detected and BCP sequences determined, including 7 anti-HCV positive who were excluded from the analysis of HCC incidence

includes 3 with deletions in this region

includes 5 with deletions in this region

Males vs. Females (Prevalence of A1762T, G1764A double mutations): X2=<0.0001, P>0.99

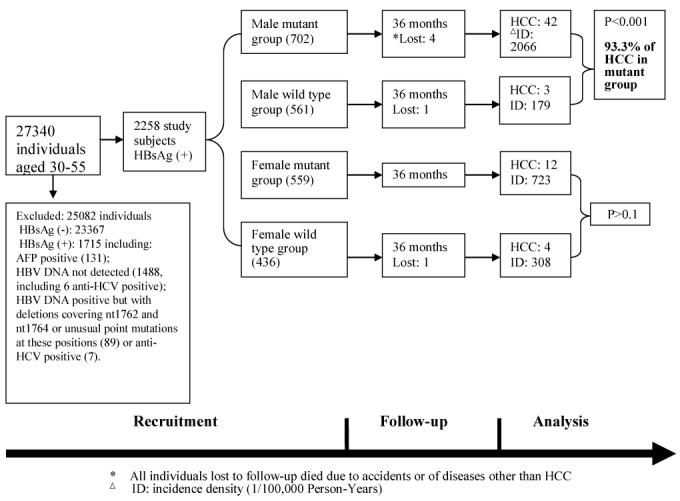

We divided the study subjects into the mutant group (double mutations, 1261 individuals) and wild type group (997 individuals). Their mean ages were 39.5±6.8 years (± standard deviation) and 37.6±7.1. With further stratification according to gender, there were 702 males in the mutant group and 561 in the wild type group, and their mean ages were 38.6±6.6 and 37.1±6.9, respectively. There were 559 females in the mutant group and 436 in the wild type group and their mean ages were 40.6±6.9 and 38.3±7.4, respectively (Fig. 1). Of the 2998 recruited initially, 740 were excluded: 638 because the BCP sequences could not be determined at baseline, 13 who were anti-HCV positive and the 89 whose BCP sequences were neither wild type nor had the specific mutations A1762T or G1764A. As controls, we also followed up 2460 HBsAg-negative individuals matched to the individuals in the study cohort in terms of sex, age and neighborhood.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the progress through the phases of the prospective study (recruitment, follow-up and data analysis).

The epidemiological characteristic of basal core promoter mutations

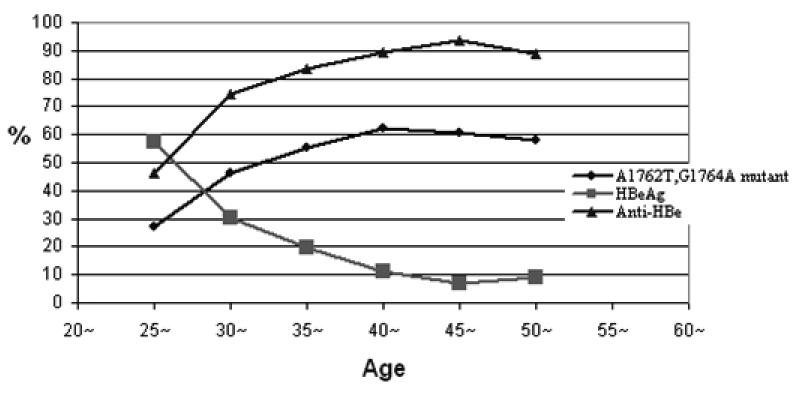

In order to confirm the accuracy and reproducibility of the tests for the basal core promoter double mutations, we re-amplified and sequenced the BCP region of HBV from 99 study subjects using the same baseline serum samples and the results are consistent. The prevalence of the mutations A1762T, G1764A is the same (53.7%) in males and females (Table 2).The prevalence tends to increase up to 35 years of age (Table 3) and parallels a decline in the prevalence of HBeAg and a rise in anti-HBe (Fig. 2). These presumed seroconversion events seem to be particularly common between the ages of 25 and 35. However, because the BCP mutations down-regulate, rather than abrogate completely, the synthesis of HBeAg, the correlation between anti-HBe and the BCP mutations is somewhat poor. For example, BCP mutations may be found in individuals with detectable HBeAg. Conversely, some individuals have anti-HBe in serum but wild type BCP sequences.

Table 3. Prevalence of HBV BCP double mutations according to age.

| Age | N | HBV DNA (+) |

A1762T, G1764A mutations |

A1762T, G1764A mutations (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-29 | 40 | 29 | 8 | 27.6 |

| 30-34 | 970 | 742 | 336 | 45.3 |

| 35-39 | 701 | 554 | 306 | 55.2 |

| 40-44 | 595 | 480 | 292 | 60.8 |

| 45-49 | 349 | 280 | 169 | 60.4 |

| 50-54 | 343 | 269 | 153 | 56.9 |

| Total | 2998 | 2354 | 1264 | 53.7 (51.7-55.7) |

Group 30-34 vs. 35-39: X2=12.171, P<0.001

Group 35-39 vs. 40-44: X2=3.080, P=0.08

Figure 2. prevalence of the A1762T, G1764A mutations, HBeAg and anti-HBe with age.

Incidence of HCC during 36 months follow-up

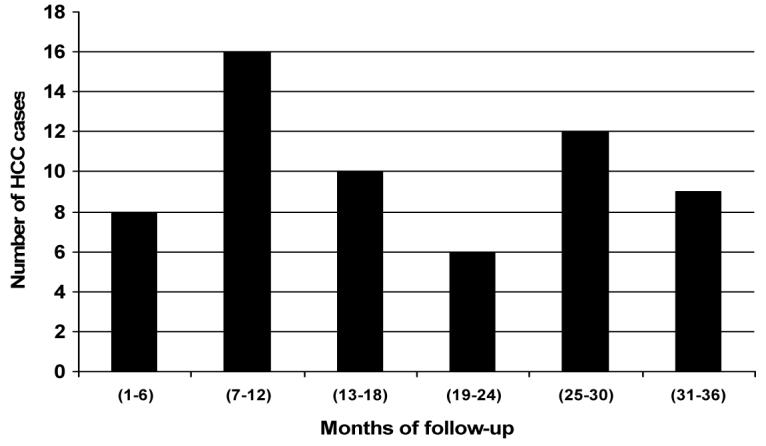

Sixty-one cases of HCC were diagnosed in the study cohort up to 36 months follow-up (Table 4, Figs 1 and 3); 54 are in the mutant group and only 7 are in the wild type group, giving HCC rates of 1463.4 vs. 235.14/100,000 person-years. The difference is significant (p<0.001), showing a strong association between the mutations and the development of HCC (rate ratio [RR]=6.23).

Table 4. HCC incidence in mutant and wild type groups after 36 months follow-up.

| Groups | N | Person-years | HCC | Incidence Rate (/100,000 years) |

95% CI | Rate ratio |

95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2258 | 6669 | 61 | 914.7 | 685.1, 1144.2 |

|||

| Mutant | 1261 | 3690 | 54 | 1463.4 | 1073.1, 1853.7 |

6.23 | 2.83, 13.68 |

0.0001 |

| Wild type | 997 | 2978 | 7 | 235.1 | 94.5, 484.2 | |||

| Males | ||||||||

| Mutant | 702 | 2031 | 42 | 2067.9 | 1442.5, 2693.3 |

11.54 | 3.58, 37.24 |

0.0001 |

| Wild type | 561 | 1675 | 3 | 179.1 | 37.0, 523.4 | |||

| Females | ||||||||

| Mutant | 559 | 1659 | 12 | 723.2 | 373.8, 1263.4 |

2.36 | 0.76, 7.31 |

0.14 |

| Wild type | 436 | 1304 | 4 | 306.7 | 83.6, 785.3 | |||

| HBsAg (-) controls |

2460 |

5985 |

1 |

16.7 |

0.4, 93.1 |

Figure 3. HCC cases diagnosed during 36 months of follow-up.

With further stratification according to gender, 42 male cases are in the mutant group and 3 in the wild type group, with rates of 2067.9 and 179.1 /100,000 person-years, respectively. Again, the difference is significant (p<0.001), showing a very strong association between the mutations and the development of HCC (RR=11.54). Specifically, 93.3% (42/45) of the male cases in the cohort are infected with the mutant type, suggesting that BCP mutations (A1762T, G1764A) may be a good biomarker to identify a subset of male HBsAg carriers at extremely high risk of HCC. Fewer cases of HCC have been diagnosed in the female study subjects, 12 mutant and 4 wild type (P>0.1) and further statistical analysis is not appropriate. The significance of the mutations for females should become clear with a longer period of follow-up. Three additional cases of HCC occurred among the 740 individuals excluded from the analysis, a male and a female whose BCP sequences could not be determined and a female with a deletion (8 nt) in the region of interest.

In the HBsAg negative control group, only one (male) developed HCC, confirming that persistent HBV infection is the major cause of HCC in this region. These data confirm our hypothesis that the mutations may be used as a biomarker to identify males in Guangxi, and perhaps elsewhere in Asia, at high risk of developing HCC.

Risk factors of HCC

Male sex, older age, and BCP double mutations at baseline were all significantly associated with an increased rate of development of HCC in univariable analyses (left-hand panel, Table 5). There was also an apparently protective effect of baseline HBeAg, although this association did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). Neither anti-HBe nor abnormal ALT levels at baseline were associated with the development of HCC. In a multivariate analysis, male sex, older age and BCP double mutations continued to be significantly associated with an increased development of HCC (middle panel, Table 5). Similar results were obtained when analyses were restricted to males only (right-hand panel, Table 5), with BCP double mutations and increasing age being independently associated with the development of HCC whereas no associations were found with HBeAg, anti-HBe or abnormal ALT concentrations.

Table 5. Analysis of factors associated with the development of HCC using Poisson regression models.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted (males only) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | RR (95% CI) | p-value | RR (95% CI) | p-value | RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Male sex | 2.25 (1.27-3.98) | 0.005 | 2.67 (1.50-4.75) | 0.0004 | n/a | ||

| Age group | 30-34 | 1 | 0.0007 | 1 | 0.0009 | 1 | 0.003 |

| 35-39 | 3.00 (1.30-6.96) | 2.74 (1.18-6.35) | 3.78 (1.36-10.48) | ||||

| 40-44 | 1.99 (0.78-5.03) | 1.76 (0.69-4.47) | 2.71 (0.91-8.09) | ||||

| 45-49 | 4.25 (1.74-10.39) | 3.88 (1.58-9.53) | 4.57 (1.49-13.99) | ||||

| 50-54 | 5.16 (2.17-12.31) | 5.36 (2.23-12.86) | 7.04 (2.36-21.00) | ||||

| BCP double mutations | 6.23 (2.83-13.68) | 0.0001 | 5.78 (2.63-12.73) | 0.0001 | 10.73 (3.32, 34.66) | 0.0001 | |

| HBeAg | 0.42 (0.17-1.05) | 0.06 | |||||

| Anti-HBe | 0.92 (0.46-1.82) | 0.81 | |||||

| Abnormal ALT | 1.58 (0.82-3.05) | 0.17 | |||||

After adjustment for sex, age and BCP double mutations, HBeAg was no longer associated with the rate of HCC and so was not included in the multivariable model.

Association with HCC of other mutations in the core promoter and enhancer II

Mutations at nucleotide (nt) 1653 from C to T and nt 1753 from T to A, G or C (T to V) have been reported to be associated with severe chronic hepatitis B and the development of cirrhosis and HCC (13). In order to determine the prevalence of these mutations in our study cohort and whether they also may be candidate biomarkers for HCC, we amplified and sequenced the X region of HBV from the study subjects with HCC and controls. The total prevalence of the C1653T mutation from cases and controls is 20% (12/60) and that of T1753V is 28.4% (29/102) (Table 6). The differences between HCC cases and controls are not significant at either position. Almost all mutations at nt 1653 and nt 1753 are co-incident with the A1762T, G1764A mutations. Whilst it was intended that all cases would be individually matched to a control (by sex, age, neighborhood and BCP sequence), this was not possible for all cases (two for nt 1653 and one for nt 1753). Thus, the main analysis (Chi-squared test) incorporated all available cases and controls but did not take account of the matching. However, a sensitivity analysis, which included only those cases and controls that were matched successfully (28 for nt 1653 and 33 for nt 1753) and utilized McNemar's test to take account of the matching, reached similar conclusions.

Table 6. Occurrence of nucleotide 1653 and 1753 mutations in individuals with HCC and controls.

| Groups | C1653T | T1753V | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mutation | Incidence (%) | N | Mutation | Incidence (%) | |

| HCC | 30 | 8 (7)* | 26.7 | 34 | 13 (13)* | 38.2 |

| Control | 30 | 4 (4) | 13.3 | 68 | 16 (13) | 23.5 |

| Total | 60 | 12 (11) | 20.0 | 102 | 29 (26) | 28.4 |

X21653=0.938 P=0.33

X21753=1.741 P=0.19

Numbers in parentheses indicate the coexistence of the C1653T and T1753V mutations with the A1762T, G1764A mutations.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this prospective study is the first designed to determine whether the incidence of HCC in subjects infected with HBV with BCP double mutations is significantly higher than that in subjects infected with HBV with wild type BCP and to clarify whether these double mutations constitute a valuable biomarker of an extremely high risk of developing HCC. After 36 months' follow-up, our data show that, in males aged >30, these mutations are an aetiological risk factor of HCC. Of note, 93.3% of male cases were infected with mutant HBV, suggesting that the A1762T, G1764A mutations are a valuable biomarker to identify a subset of male HBsAg carriers aged >30 at extremely high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. The major weakness of this study is that the role of viral loads which have been reported to be associated with the development of HCC (10, 14, 15) has not been studied in detail because of the high cost of quantitation, although measurement of viral loads in a representative sample of individuals from this cohort showed that the BCP double mutations are not associated with higher viral loads (in fact, HBeAg-positive individuals with BCP double mutations have significantly lower viral loads than those with wild type HBV; data not shown). Another weakness is that, with this limited period follow-up, it is not clear whether the BCP double mutations are associated with the development of HCC in females, because only a small number of HCC cases has been diagnosed because of the lower incidence of HCC in females (HCC is approximately four times more common in males than females).

Although HBV genotypes have been reported to be of clinical relevance (9), their role in the development of HCC remains controversial (10-14, 27). Furthermore, our random genotyping of this cohort shows that the distribution of genotypes in subjects without HCC is similar to that in HCC (data not shown).Therefore we did not determine the HBV genotype for all study subjects. The incidence of HCC in HBV cirrhotic patients has been found to be greater than in non-cirrhotic patients (28). In this study, 67 individuals were known to have cirrhosis and 39 of the 61 HCC cases occurred in individuals with cirrhosis (data not shown). However, BCP double mutations, per se, are an independent risk factor for the development of liver cirrhosis (18, 29) and cirrhosis was not included in this analysis.

Since Chu et al. (19) and we (17) reported that BCP double mutations are associated with the development of HCC, there have been many studies that confirm these findings (14, 20, 21). It has been suggested that the double mutations may serve as a useful molecular marker for predicting the clinical outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis B (21) and might contribute to the gender difference in the progression of liver disease in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B (30). A retrospective nested case-control study showed that the BCP double mutations were statistically significantly associated with HCC risk, even after adjusting for ALT levels, anti-HBe, HBV genotype, HBV viral load, and other sequence variants (31). However, these are all cross-sectional or case-control studies and cannot prove the etiological relationship between BCP mutations and the development of HCC, or determine the incidence of HCC. One retrospective longitudinal analysis determined that the patients had these mutations prior to diagnosis of HCC (32) and confirms that the BCP mutations play an etiological role in the development of HCC. However, this is a small retrospective study (120 study subjects); sampling bias could not be avoided and it was not possible to determine the incidence of HCC in the BCP mutant and wild type groups. Our prospective study overcomes all of these problems.

Other studies have suggested that the core promoter mutations C1653T and T1753V also are associated with the occurrence of severe hepatitis B and development of HCC, although their prevalence is lower than that of the A1762T, G1764A mutations (13, 33-35). In this study cohort, the C1653T and T1753V mutations were detected less frequently (from 20%-28.4%) than the A1762T, G1764A mutations and the differences between HCC cases and controls are not significant for either. Furthermore, the C1653T and T1753V mutations occur almost invariably on the background of the A1762T, G1764A mutations. Therefore, we conclude that the A1762T, G1764A mutations are a valuable biomarker to identify those male HBsAg carriers who should be monitored regularly for signs of tumour.

It might seem that the value of this biomarker is limited, given that the mutations were detected in around half of the HBV DNA-positive individuals in our cohort. However, we believe that this extremely high prevalence of the mutations is attributable to our conducting this prospective study in an area amongst the highest in the world in terms of annual incidence of HCC. Our earlier studies (17, 18) reported a prevalence of the mutations in around one quarter of HBV DNA-positive individuals elsewhere in Guangxi and studies in neighboring provinces show a prevalence ranging from 10% (Guangdong (36)) to 30% (Hunan (37)). Therefore, we consider it worthwhile to screen HBsAg carriers for the mutations in areas where there is a high annual incidence of HCC. Currently, in Guangxi, China, HBsAg positive males aged >30 are considered as higher risk population of HCC (22-24) and recommended to undergo regular surveillance for HCC. Considering the high prevalence of HBsAg and the limited public health resources in Guangxi and in other highly endemic areas, it is recommended to narrow down further the number of subjects requiring surveillance for HCC using the biomarker of BCP double mutations, despite that this will result in failure to detect around 7% of HCC cases, which occur in the male population infected with HBV with wild type BCP sequences.

We found at baseline that the prevalence of HBV with BCP double mutations increases with age and differs significantly between age groups 30-34 and 35-39, and 35-39 and 40-44. In future, we will repeat the assays on samples collected longitudinally to determine the rate at which this shift occurs and whether wild type HBV re-emerges in individuals in whom the variant viruses were selected previously.

High viral loads (≥104 copies/ml) have been reported to be associated with the development of HCC (10, 14, 15) and also are of importance in this study cohort. As described in the paragraph covering grouping of study subjects, 1402 HBsAg positive individuals were HBV DNA negative with the PCR conducted originally in China. Subsequently, we measured the viral loads of 34 random male subjects from the DNA ‘initially DNA negative’ group and 98 random male subjects from the DNA positive group. Serum viral DNA concentrations were ≥104 copies/ml in 17.6% (6/34) of the DNA ‘negative’ group and 89.8% (88/98) of the DNA positive group (data not shown). After 36 months follow-up, only 10 HCC cases were found in these “initially DNA negative” male subjects (1.39%, 10/719) compared to 36 cases in DNA positive group (3.92%, 36/919). We also measured the baseline viral loads of 20 male HCC cases from which sufficient serum remained available; 85% (17/20) are ≥104 copies/ml (data not shown). In the future, we shall assess further the role of viral loads in the development of HCC in this cohort, and determine whether this factor acts independently of, or synergistically with, the BCP mutations and whether viral loads can be used as an additional biomarker to narrow down further the population at risk (i.e. those identified with BCP double mutations). Meanwhile, we will continue to follow up our cohort to determine whether the BCP mutations have the same value as a biomarker in females.

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

1) What Is Current Knowledge

- Surgery remains the only curative modality for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

- Surveillance can detect small HCC for resection but at huge cost in health resources

- It is difficult to narrow down the population for surveillance of HCC

2) What Is New Here

- Hepatitis B virus (HBV) A1762T, G1764A mutations are a valuable biomarker to identify males at extremely high risk of HCC

- The number of males for surveillance for HCC can be narrowed down according to the presence of HBV A1762T, G1764A mutations

- HBV A1762T, G1764A mutations are an etiological risk factor of HCC

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (award number 072058/Z/03/Z) and by the Government of Guangxi, China. We are indebted to staff members of Long An Sanitary and Antiepidemic Station and local hospitals in Long An county, Guangxi who assisted in recruiting the study subjects, sample collection, and ultrasonographic examinations of the livers for HCC and to staff members of the Department of Virology, Centre for Disease Prevention and Control of Guangxi, China for their help in recruiting the study subjects and handling the sera.

Financial support: This study is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (award number 072058/Z/03/Z) and by the Government of Guangxi, China.

Footnotes

Potential competing interests: None

REFERENCES

- 1.McGlynn KA, London WT. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:3–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Mortality database. WHO Statistical Information System; 2001. Available at: http://www.who.int/whosis. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang ZY, Yu YQ, Zhou XD, Ma ZC, Wu ZQ. Progress and prospects in hepatocellular carcinoma surgery. Ann Chir. 1998;52:558–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuen MF, Cheng CC, Lauder IJ, Lam SK, Ooi CG, Lai CL. Early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma increases the chance of treatment: Hong Kong experience. Hepatology. 2000;31:330–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, Chien CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. A prospective study of 22 707 men in Taiwan. Lancet. 1981;2:1129–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, Sastrosoewignjo RI, Imai M, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2575–83. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-10-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ArauzRuiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO. Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2059–73. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao JH. Hepatitis B viral genotypes: Clinical relevance and molecular characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:643–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu MW, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, Liaw YF, Lin CL, Liu CJ, Shih WL, Kao JH, Chen DS, Chen CJ. Hepatitis B virus genotype and DNA level and hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective study in men. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2005;97:265–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan HLY, Hui AY, Wong ML, Tse AML, Hung LCT, Wong VWS, Sung JJY. Genotype C hepatitis B virus infection is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2004;53:1494–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumi H, Yokosuka O, Seki N, Arai M, Imazeki F, Kurihara T, Kanda T, Fukai K, Kato M, Saisho H. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the progression of chronic type B liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:19–26. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Shinkai N, Poon RT, But DY, Fong DY, Fung J, Wong DK, Yuen JC, Mizokami M, Lai CL. Risk for hepatocellular carcinoma with respect to hepatitis B virus genotypes B/ C, specific mutations of enhancer II/ core promoter/ precore regions and HBV DNA levels. Gut. 2008;57:98–102. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CJ, Chen BF, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Huang WL, Kao JH, Chen DS. Role of hepatitis B virus precore/core promoter mutations and serum viral load on noncirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-control study. J Inf Dis. 2006;194:594–9. doi: 10.1086/505883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohata K, Hamasaki K, Toriyama K, Ishikawa H, Nakao K, Eguchi K. High viral load is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:670–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen BF, Liu CJ, Jow GM, Chen PJ, Kao JH, Chen DS. High prevalence and mapping of pre-S deletion in hepatitis B virus carriers with progressive liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1153–68. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang ZL, Ling R, Wang SS, Nong J, Huang CS, Harrison TJ. HBV core promoter mutations prevail in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from Guangxi, China. J Med Virol. 1998;56:18–24. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199809)56:1<18::aid-jmv4>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang ZL, Yang JY, Ge XM, Zhuang H, Gong J, Li RC, Ling R, Harrison TJ. Core promoter mutations (A(1762)T and G(1764)A) and viral genotype in chronic hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma in Guangxi, China. J Med Virol. 2002;68:33–40. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu CHC, Hao YW, Tabor E. Hot-spot mutations in hepatitis B virus X gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 1996;348:625–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64851-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baptista M, Kramvis A, Kew MC. High prevalence of 1762(T) 1764(A) mutations in the basic core promoter of hepatitis B virus isolated from black Africans with hepatocellular carcinoma compared with asymptomatic carriers. Hepatology. 1999;29:946–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Basal core promoter mutations of hepatitis B virus increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B carriers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:327–34. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang ST, Lin JL, Lu YF, Wu S, Liao QH, Li LQ. Analysis on influential factor for long-term survival in patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Guangxi Med J. 1994;16:465–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu YF, Lin JL, Liang ST, Li LQ, Liao QH, Zeng J, Zhou HS, Qin X, Wu S. Surgical treatment of primary liver cancer: An analysis of postoperative prognosis of 257 cases. Guangxi Med J. 1998;20:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li XP, Mo MS, Huang JC. Clinical significamce of early screening for the high risk crowd of primary liver cancer. Guangxi Med J. 2005;27:1729–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh FS, Yu MC, Mo CC, Luo S, Tong MJ, Henderson BE. Hepatitis B virus, aflatoxins, and hepatocellular carcinoma in southern Guangxi, China. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2506–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunther S, Li BC, Miska S, Kruger DH, Meisel H, Will H. A novel method for efficient amplification of whole hepatitis B virus genomes permits rapid functional analysis and reveals deletion mutants in immunosuppressed patients. J Virol. 1995;69:5437–44. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5437-5444.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tangkijvanich P, Mahachai V, Komolmit P, Fongsarun J, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and hepatocellular carcinoma in Thailand. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2238–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i15.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monto A, Wright TL. The epidemiology and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:441–9. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CH, Lee CM, Lu SN, Changchien CS, Eng HL, Huang CM, Wang JH, Hung CH, Hu TH. Clinical significance of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes and precore and core promoter mutations affecting HBV e antigen expression in Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:6000–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6000-6006.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CL, Liao LY, Wang CS, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS, Kao JH. Basal core-promoter mutant of hepatitis B virus and progression of liver disease in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2005;25:564–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chou YC, Yu MW, Wu CF, Yang SY, Lin CL, Liu CJ, Shih WL, Chen PJ, Liaw YF, Chen CJ. Temporal relationship between hepatitis B virus enhancer II/basal core promoter sequence variation and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2008;57:91–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.114066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuang SY, Jackson PE, Wang JB, Lu PX, Munoz A, Qian GS, Kensler TW, Groopman JD. Specific mutations of hepatitis B virus in plasma predict liver cancer development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3575–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka Y, Mukaide M, Orito E, Yuen MF, Ito K, Kurbanov F, Sugauchi F, Asahina Y, Izumi N, Kato M, Lai CL, Ueda R, Mizokami M. Specific mutations in enhancer II/core promoter of hepatitis B virus subgenotypes C1/C2 increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2006;45:646–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan J, Zhou B, Tanaka Y, Kurbanov F, Orito E, Gong Z, Xu L, Lu J, Jiang X, Lai W, Mizokami M. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes/subgenotypes in China: Mutations in core promoter and precore/core and their clinical implications. J Clin Virol. 2007;39:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang ZH, Tanaka Y, Huang YH, Kurbanov F, Chen JJ, Zeng GB, Zhou B, Mizokami M, Hou JL. Clinical and virological characteristics of hepatitis B virus subgenotypes Ba, C1, and C2 in China. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1491–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02157-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou JL, Lau GKK, Cheng JJ, Cheng CC, Luo KX, Carman WF. T-1762/A(1764) variants of the basal core promoter of hepatitis B virus; serological and clinical correlations in Chinese patients. Liver. 1999;19:411–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong GZ, Ding Q, Zheng XH, Li LY, Lai LY, Huang L. [Relationship between hot spot mutation in hepatitis B virus basic core promoter and HBeAg status] Hunan Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2000;25:561–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]