Abstract

Drugs used to treat various disorders target GABAA receptors. To develop α subunit selective compounds, we synthesized 5-(4-piperidyl)-3-isoxazolol (4-PIOL) derivatives. The 3-isoxazolol moiety was substituted by 1,3,5-oxadiazol-2-one, 1,3,5-oxadiazol-2-thione, and substituted 1,2,4-triazol-3-ol heterocycles with modifications to the basic piperidine substituent as well as substituents without basic nitrogen. Compounds were screened by [3H]muscimol binding and in patch-clamp experiments with heterologously expressed GABAA αiβ3γ2 receptors (i = 1–6). The effects of 5-aminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one 5d were comparable to GABA for all α subunit isoforms. 5-piperidin-4-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one 5a and 5-piperidin-4-yl-3H- [1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione 6a were weak agonists at α3–, α3–, and α5–containing receptors. When coapplied with GABA they were antagonistic inα2–, α4–, and α6–containing receptors and potentiated α3-containing receptors. 6a protected GABA binding site cysteine-substitution mutants α1F64C and α1S68C from reacting with methanethiosulfonate-ethylsulfonate. 6a specifically covalently modified the α1R66C thiol, in the GABA binding site, through its oxadiazolethione sulfur. These results demonstrate the feasibility of synthesizing α subtype selective GABA mimetic drugs.

Introduction

γ-Aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAA) are responsible for most of the fast inhibitory synaptic transmission in mammalian brain. They belong to the Cys-loop receptor superfamily of ligand-gated ion channels. These receptors are formed by the pentameric assembly of homologous subunits and contain an anion-selective transmembrane channel. Numerous GABAA receptor subunits have been identified (α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ π, ε and θ), all of which are products of separate genes1–3. Most GABAA receptors contain two α, two β subunits and either a γ or a δ subunit. Recombinant GABAA receptors with different subunit isoform composition display differing sensitivity to the endogenous agonist GABA4. The GABAA receptor subunits exhibit distinct, although overlapping, regional distribution patterns within the brain, with expression patterns changing during pre- to postnatal development5. In addition, in neurons expressing multiple receptor isoforms, subunit-selective targeting to distinct cellular domains has been observed6, 7. The subunit isoform diversity and brain region specific expression patterns form the basis for the functional and pharmacological heterogeneity of GABAergic neurotransmission. Presently, most drug therapy for anxiety, epilepsy and surgical sedation and often for insomnia targets GABAA receptor subtypes non-selectively, but the heterogeneity of the receptors theoretically holds the promise for brain region- or even cell-selective pharmacological intervention which would increase the specificity of the effects and decrease the incidence of undesirable side effects.

Most of the known pharmacological heterogeneity of GABAA receptors concerns the sensitivity of the benzodiazepine site that is formed at the interface between the α and γ subunits8–10. Receptors lacking the γ2 subunit or containing the α4 or α6 subunits are practically insensitive to benzodiazepine site agonists11, 12, 13, 14. The two GABA binding sites are formed at the interfaces between the β and α subunits. Only a few different structural classes of ligands are known for the GABA binding site, reflecting the strict structural requirements for GABAA receptor recognition and activation. To date these GABA binding site agonist compounds display little subunit subtype specificity with gaboxadol forming a class on its own as a “superagonistic” GABA mimetic15. A few compounds have been identified which neither bind to the benzodiazepine nor the GABA binding sites and yet still show subtype-selective antagonistic activity, these include furosemide, otherwise known as a Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter blocker, that selectively blocks α(4/6) β(2/3) γ2 receptors16, 17, and clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic drug, that inhibits furosemide-insensitive α1 containing receptors18.

Undesirable side effects, such as sedation and amnesia, often limit the clinical use of benzodiazepines19, as well as the use of full agonists and of zero modulators of the GABA recognition site20. Different strategies exist to minimize undesirable effects: subtype-selective ligands or partial agonists. Studies with transgenic rodents have helped to dissect the α-subunit isoforms involved in specific pharmacologic effect of benzodiazepines. For example, α2-containing receptors are primarily responsible for anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines whereas α1-containing receptors are more important for the sedative side effects. Current research efforts focused on designing subunit-selective benzodiazepines21–27. In general, it seems desirable to have subtype-selective ligands that only act on a certain receptor subtype that is involved in transducing the desired effect and not on other subtypes that are involved in undesired effects. A complementary approach is to develop partial agonists of the GABA recognition site that induce only submaximal activation of specific α-subunit containing receptors. Under close to complete receptor occupancy, these partial agonists act as inhibitors of full agonists15. Partial agonists at the benzodiazepine site have also been investigated28–30.

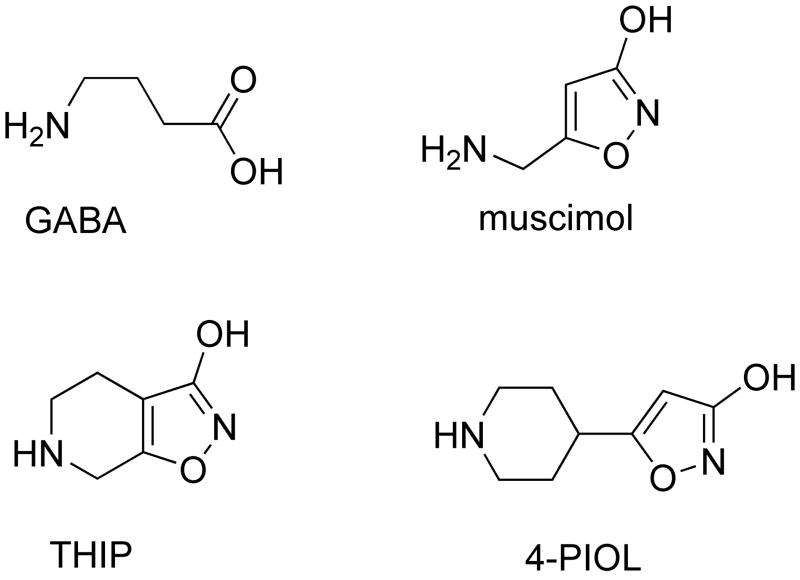

In a previous study we used binding studies on rat brain cryostat sections and patch-clamp experiments with heterologously expressed recombinant GABAA receptors to characterize the low-efficacy GABA mimetic 5-(4-piperidyl)isoxazol-3-ol (4-PIOL) (Figure 1) as a weak partial agonist or antagonist depending on the brain area and the GABAA receptor composition31,32. Therefore we synthesized and functionally characterized different 5-(4-piperidyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol- and 5-(4-piperidyl)-1,3,4-triazol-derivatives compounds structurally related to 4-PIOL33. The effects of other 4-PIOL derivatives on GABAA receptors have been studied previously34–40. All compounds were screened for efficacy and potency to GABAA receptors in native membranes using a [3H]muscimol binding assay. Substances inducing changes in [3H]muscimol binding in the micromolar concentration range were further analyzed in patch clamp recordings from GABAA receptors heterologously expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells. The α subunit specificity of these compounds was tested in αiβ3γ2 (i = 1–6) GABAA receptors by measuring the modulation of GABA-induced chloride current and the intrinsic activity of the compounds. We also sought to demonstrate that the actions of these new compounds were mediated through binding at the GABA-binding sites. We used a variant of the substituted cysteine accessibility method (SCAM) in order to identify the position and orientation of 6a in the binding site41. Residues in the α subunit that line the GABA binding site have been identified based on the effects of mutations on electrophysiological properties 42–44, photo-affinity labeling 45 and SCAM 46–48. They include those aligned with rat α1 positions F64, R66, S68 and T129. Although crystal structures of GABAA receptor binding sites are not yet available, homology models based on the snail acetylcholine binding protein (AChBP) structure provide a reasonable molecular context in which to interpret our results 49.

Figure 1.

Structures of GABA, muscimol, THIP and 4-PIOL.

Synthesis

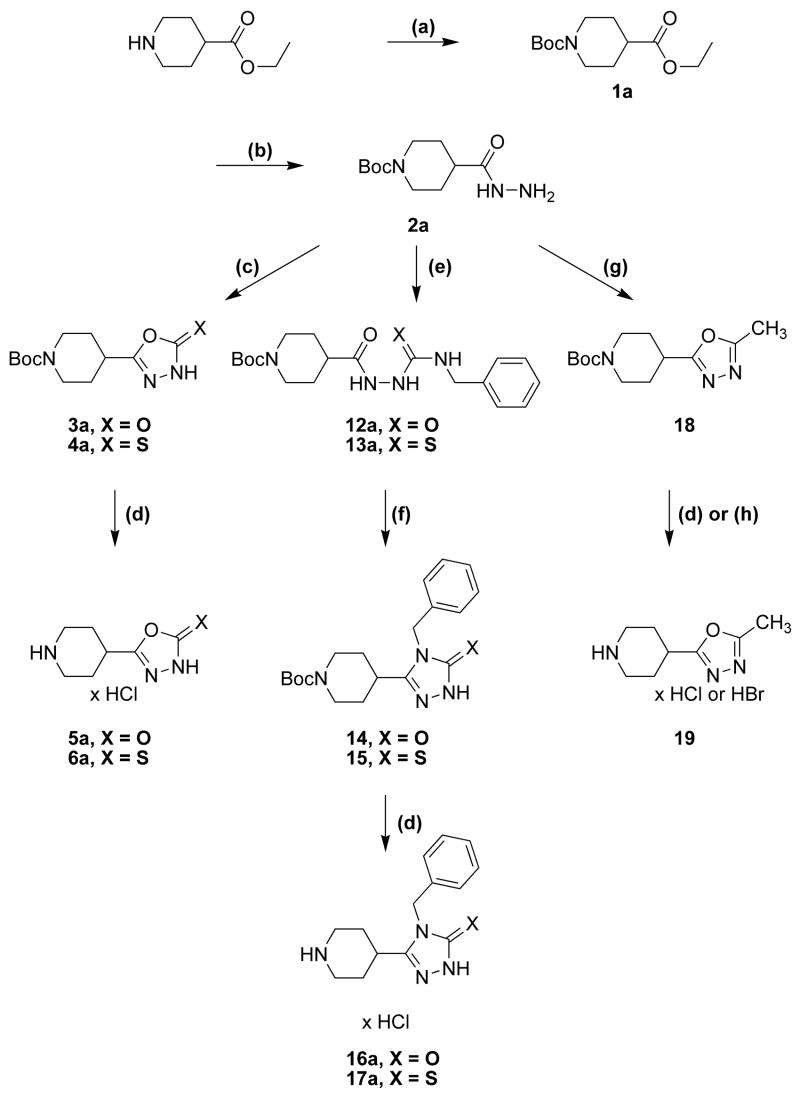

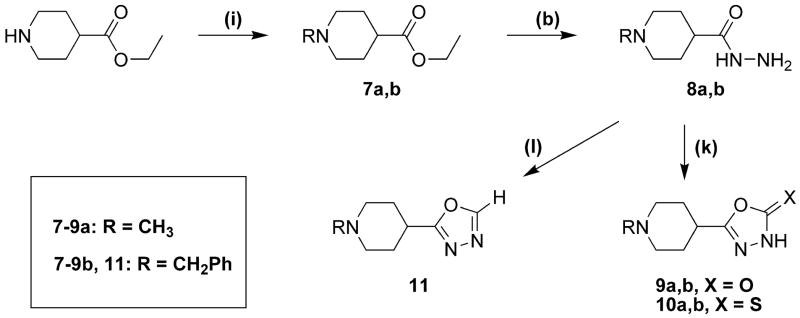

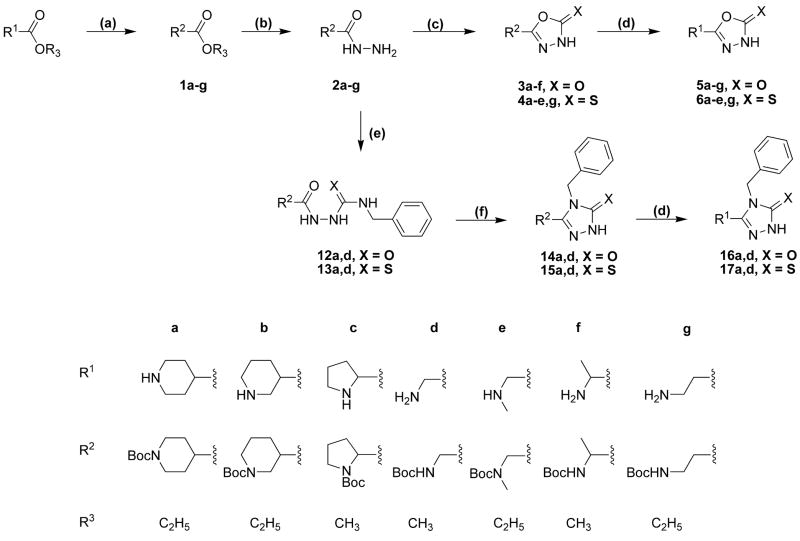

The synthetic procedures for the 5-(4-piperidyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole- and 5-(4-piperidyl)-1,3,4-triazole-derivatives in this study are depicted in scheme 1 and scheme 2, whereas schemes 3 and 4 depict specific variations of the 4-piperidyl moiety. Here we describe the synthesis of the 4-piperidyl-derivatives as an example. The secondary amine function of 4-piperidine-carboxylic acid ester was either protected with the t-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group using di-t-butyldicarbonate and NaHCO3 in water or triethylamine in methylene chloride (Scheme 1: 1a) or alkylated using formaldehyde, formic acid or benzylchloride (Scheme 2: 7a, b). Subsequently, the esters were converted to the corresponding acid hydrazides (Scheme 1: 2a; Scheme 2: 8a, b) by refluxing the ester in an excess of hydrazine hydrate. The 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-ones (Scheme 1: 3a; Scheme 2: 9a, b) were prepared by refluxing the hydrazides with N,N′-carbonyldiimidazol (CDI) in the presence of triethylamine in a mixture of THF and DMF. The corresponding 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-thiones (Scheme 1: 4a; Scheme 2: 10a, b) were synthesized by refluxing the hydrazides with carbonyldisulfide in an ethanolic potassium hydroxide solution. Theoretically, oxadiazol-2-ones and –thiones can exist in two tautomeric forms, the amide form and the imino-alcohol form. IR, UV and NMR spectra, however, indicate that they exist predominantly in their amide-form50. The hydrazide 2a was also cyclized with triethoxyethane to yield the 2-methyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-derivative (Scheme 1: 18). Reaction of the hydrazide 2a with benzylisocyanate or benzylisothiocyanate produced the acylated semicarbazide derivatives 12a and 13a, which were converted to benzyl-1,3,4-oxadiazoles 14 and 15 by refluxing with NaOH in an aqueous solution (Scheme 1). N-methyl-piperidin-4-yl carboxylic acid hydrazide (8b) was reacted with triethoxymethane to yield the 2-unsubstituted 1,3,4-oxadiazol-derivative 11 (Scheme 2). The 4-piperidyl moiety was varied as outlined in Scheme 3 and 4. It was substituted by a 3-piperidyl and a 2-pyrrolidinyl moiety, or residues that lead to derivatives that mimic glycine, sarcosine, alanine and β-alanine (Scheme 3) as well as N-alkylated 4-piperidinyl-compounds, dimethylglycine and two compounds without an amine function (Scheme 4). The last step during the synthesis of compounds 5a–g, 6a–e, g, 16a, 17a, and 19 was the removal of the Boc-protective group with hydrogen chloride (Scheme 1 and 3).

Scheme 1a.

a Reaction conditions: (a) Et3N, Boc2O in CH2Cl2 or NaHCO3, Boc2O in water; (b) NH2NH2; (c) CDI to obtain 3; CS2 to obtain 4; (d) 2.3 N ethanolic HCl; (e) PhCH2NCX; (f) 2% NaOH; (g) H3CC(OC2H5)3; (h) HBr/HAc.

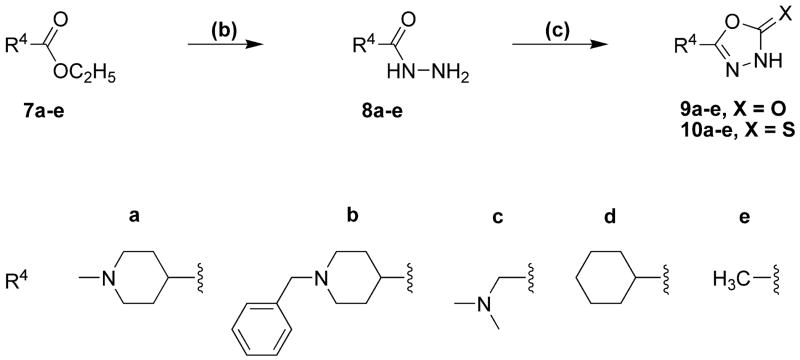

Scheme 2a.

a Reaction conditions: (b) NH2NH2; (i) CH2O, HCOOH to obtain 7a; PhCH2Cl to obtain 7b; (k) triphosgene to obtain 9a,b; CS2 to obtain 10a,b; (l) HC(OC2H5)3.

Scheme 3a.

a Reaction conditions as given in Scheme 1 and Scheme 2.

Scheme 4a.

a Reaction conditions as given in Scheme 1 and Scheme 2.

Pharmacology

[3H]Muscimol binding

Compounds were initially screened by probing their ability to compete with [3H]muscimol binding to the GABA recognition site in native cortical and cerebellar membranes. We used two concentrations (100 μM and 1 mM) of the compounds. This approach allowed us to eliminate compounds with very low binding affinity. Additionally, we compared the binding of [3H]muscimol to membranes from two brain structures: cortex, containing α1–α5 receptors, and cerebellum, enriched in α1- and the exclusive source of α6-containing GABAA receptors (Table 1), to enable us to detect pronounced differences in subtype selectivity of the compounds.

Table 1.

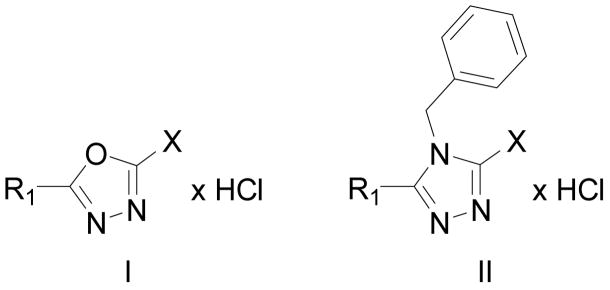

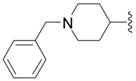

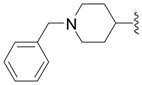

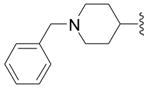

Percent inhibition of [3H]muscimol binding to well-washed membranes from rat cortex and cerebellum by 100 μM and 1 mM of test compounds. Given are the means ± S.D. with the number of experiments in brackets. Compound 17a was insoluble at 1 mM and therefore not tested at this concentration. Structure I applies except were II is specifically indicated. Compounds for which an IC50 is reported in Table 2 are shaded grey.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | R | X | cortex | cerebellum | ||

| 100 μM | 1 Mm | 100 μM | 1 mM | |||

| 5a |

|

OH | 38 ± 15 (4) | 79 ± 7 (4) | 38 ± 20 (4) | 77 ± 11 (4) |

| 5b |

|

OH | 1 ± 11 (3) | 24 ± 5 (4) | 9 ± 9 (4) | 10 ± 7 (4) |

| 5c |

|

OH | 5 ± 7 (3) | 10 ± 3 (3) | 8 ± 1 (3) | 13 ± 4 (3) |

| 5d |

|

OH | 99 ± 4 (3) | 104 ± 2 (3) | 97 ± 6 (3) | 102 ± 6 (3) |

| 5e |

|

OH | 14 ± 3 (3) | 58 ± 4 (3) | 22 ± 3 (3) | 64 ± 1 (3) |

| 5f |

|

OH | 26 ± 25 (3) | 16 ± 4 (3) | 13 ± 17 (3) | 34 ± 4 (3) |

| 5g |

|

OH | 85 ± 5 (3) | 100 ± 1 (3) | 89 ± 1 (3) | 98 ± 0 (3) |

| 6a |

|

SH | 68 ± 5 (4) | 94 ± 2 (4) | 64 ± 9 (4) | 91 ± 2 (4) |

| 6b |

|

SH | 12 ± 17 (4) | 51 ± 9 (4) | 15 ± 3 (4) | 42 ± 5 (4) |

| 6c |

|

SH | 21 ± 19 (3) | 36 ± 6 (3) | −2 ± 0 (3) | 31 ± 4 (3) |

| 6d |

|

SH | 58 ± 14 (3) | 99 ± 9 (3) | 61 ± 1 (3) | 95 ± 2 (3) |

| 6e |

|

SH | 17 ± 1 (3) | 24 ± 9 (3) | 9 ± 9 (3) | 16 ± 4 (3) |

| 6g |

|

SH | 9 ± 7 (3) | 61 ± 6 (3) | 23 ± 5 (3) | 67 ± 1 (3) |

| 9a |

|

OH | 4 ± 7 (4) | 27 ± 5 (4) | 6 ± 5 (4) | 26 ± 6 (4) |

| 9b |

|

OH | 12 ± 6 (4) | 50 ± 3 (4) | 7 ± 4 (4) | 30 ± 8 (4) |

| 9c |

|

OH | 3 ± 1 (3) | 27 ± 5 (3) | 5 ± 5 (3) | 26 ± 3 (3) |

| 9d |

|

OH | 18 ± 1 (3) | −2 ± 7 (3) | −11 ± 11 (3) | 1 ± 12 (3) |

| 9e |

|

OH | 7 ± 11 (3) | 26 ± 3 (3) | 3 ± 4 (3) | 4 ± 7 (3) |

| 10a |

|

SH | 6 ± 6 (4) | 48 ± 6 (4) | 8 ± 10 (4) | 27 ± 8 (4) |

| 10b |

|

SH | 3 ± 13 (4) | 33 ± 14 (4) | 6 ± 2 (4) | 30 ± 5 (4) |

| 10c |

|

SH | 22 ± 8 (3) | 47 ± 7 (3) | 3 ± 8 (3) | 37 ± 6 (3) |

| 10d |

|

SH | 10 ± 1 (3) | 18 ± 2 (3) | 0 ± 8 (3) | −3 ± 3 (3) |

| 10e |

|

SH | 20 ± 4 (3) | 10 ± 1 (3) | −4 ± 4 (3) | −3 ± 10 (3) |

| 11 |

|

H | −5 ± 3 (3) | 1 ± 1 (3) | 1 ± 3 (3) | −5 ± 4 (3) |

| 16a (II) |

|

OH | 18 ± 3 (3) | 56 ± 3 (3) | 14 ± 1 (3) | 52 ± 2 (3) |

| 16d (II) |

|

OH | 4 ± 3 (3) | 11 ± 1 (3) | 1 ± 4 (3) | 2 ± 4 (3) |

| 17a (II) |

|

SH | −6 ± 11 (3) | - | 13 ± 18 (3) | - |

| 17d (II) |

|

SH | * | * | * | * |

| 19 |

|

-CH3 | 48 ± 8 (3) | 87 ± 5 (3) | 56 ± 5 (3) | 91 ± 1 (3) |

inactive.

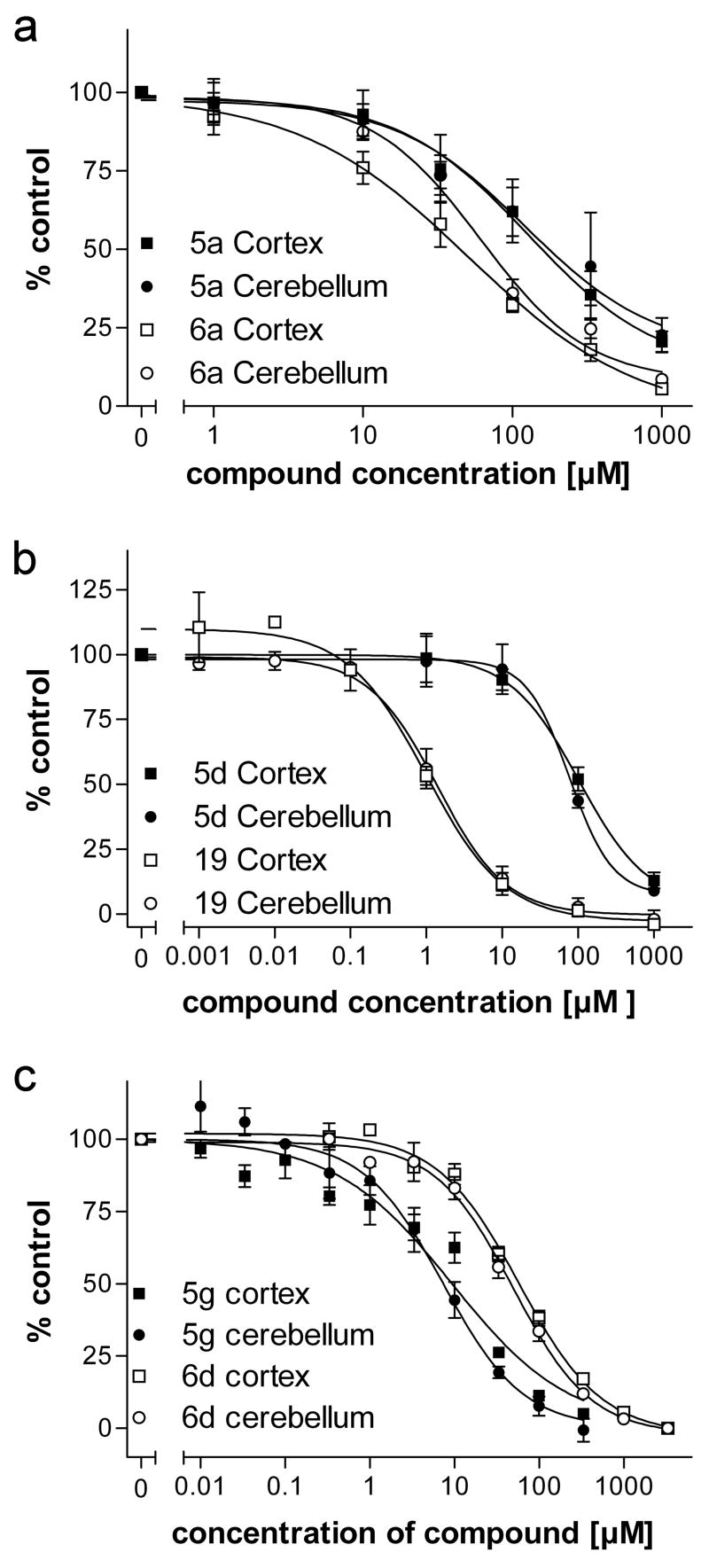

Of the 28 compounds tested, six fulfilled our criteria for full binding analysis in that, at 100 μM, they inhibited muscimol binding by at least 30% (Table 1). These six included 5a, 5d, 5g, 6a, 6d and 19. For these compounds we determined the IC50 values for inhibition of [3H]muscimol binding to cortical and cerebellar membranes (Table 2, 5d Figure 2). showed the highest affinity with an IC50 of 1.4 μM and 5a exhibited the lowest affinity, 183 μM (Table 2). None of the six compounds displayed significant differences between IC50 determined in cortical vs cerebellar membranes, though compound 5g showed a significant difference between the pseudo-Hill coefficient determined in cortical vs cerebellar membranes, 0.63 vs 0.92, respectively, whereas no difference in any measure was detected for the other compounds (Table 2).

Table 2.

Binding parameters of selected compounds against 6 nM [3H]muscimol in crude membrane preparations of rat cortex and cerebellum determined by nonlinear regression. Given are the means ± S.E.M. of the decadic logarithm of the IC50 in μM, the corresponding pseudo-Hill coefficient η and the number of experiments n.

| Cortex | Cerebellum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lg IC50 | IC50 [μM] | η | n | lg IC50 | IC50 [μM] | η | n | |

| 5a | 2.262 ± 0.185 | 183 | 0.86 ± 0.10 | 4 | 2.089 ± 0.170 | 123 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 3 |

| 5d | 0.139 ± 0.119 | 1.4 | 1.12 ± 0.13 | 3 | 0.048 ± 0.082 | 1.1 | 0.90 ± 0.21 | 3 |

| 5g | 0.971 ± 0.074 | 9.4 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 4 | 0.868 ± 0.065 | 7.4 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | 3 |

| 6a | 1.668 ± 0.153 | 47 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 3 | 1.819 ± 0.048 | 66 | 1.03 ± 0.08 | 4 |

| 6d | 1.758 ± 0.074 | 57 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 3 | 1.690 ± 0.081 | 49 | 0.96 ± 0.12 | 4 |

| 19 | 2.039 ± 0.067 | 109 | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 3 | 1.879 ± 0.081 | 76 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 3 |

Table 5.

Summary of dose-response data and 6a competition data using a GABA EC20 concentration from cysteine-substituted and wt α1β2 GABAA receptors.

| Receptor | GABA

|

6a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μM) | mutant/wt | n | EC50 (mM) | n | IC50 (μM) | n | |

| α1β2 wt | 10.0 ± 1.2 | 1 | 6 | 9.5 ± 0.02 | 2 | 59 ± 6 | 4 |

| α1F64C β2 | 430 ± 40 | 43 | 6 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 4 | 56 ± 12 | 3 |

| α1R66C β2 | 5540 ± 210 | 554 | 6 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

| α1S68C β2 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 0.65 | 5 | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 2 | 46 ± 5 | 3 |

| α1T129C β2 | 136 ± 6 | 13.6 | 6 | n.d. | n.d. | ||

Figure 2.

Dose-response curves as measured against [3H]muscimol binding to cortical (squares) and cerebellar (circles) membranes. Binding data were normalized to the binding in the absence of any inhibitor set to 100%. Error bars indicate the S.E.M for at least three independent tissue preparations.

HEK293 Electrophysiology

We characterized the functional effects of four compounds on αiβ3γ2 (i = 1–6) GABAA receptors using patch-clamp experiments with heterologously expressed GABAA receptors. This allowed us to determine directly the GABAA receptor α subunit specificity for these four compounds identified as the most potent inhibitors in the [3H]muscimol binding assays described above. Transiently transfected HEK 293 cells co-expressing an α variant plus β2 and γ2S and Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) were used in these experiments. EGFP fluorescence facilitated the identification of transfected cells for patch clamping. For each compound we applied a series of increasing drug concentrations either alone, to assess the intrinsic agonist activity, or together with the approximate EC20 to EC25 concentration of GABA, to determine its GABA-modifying activity. The GABA EC20–25 concentrations used for the different α subunits are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

GABA concentrations and the corresponding relative effective concentration that induces a response around the EC20 when applied to GABAA receptors αiβ3γ2 (i=1–6) transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells. Given are the mean ± S.E.M.

| αsubunit | GABA [μM] | EC |

|---|---|---|

| α1 | 2.0 | 25 ± 2.3 |

| α2 | 4.0 | 24 ± 1.9 |

| α3 | 8.0 | 22 ± 2.1 |

| α4 | 5.0 | 25 ± 2.0 |

| α5 | 3.0 | 22 ± 2.1 |

| α6 | 0.5 | 20 ± 2.2 |

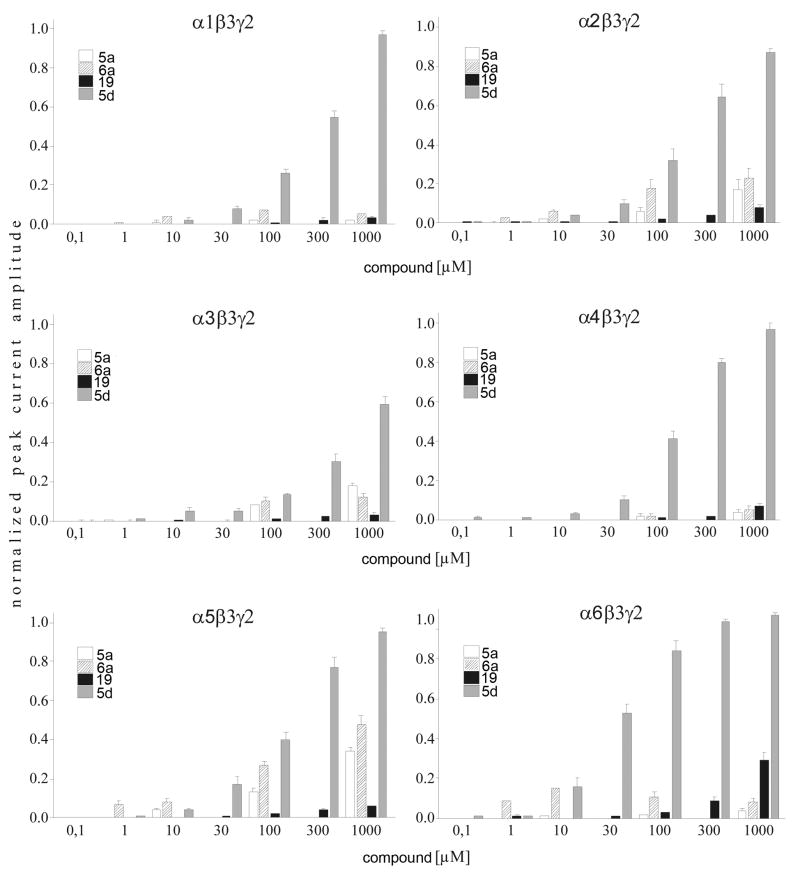

Intrinsic agonist activity

5a (5-Piperidin-4-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one hydrochloride) and 6a (5-Piperidin-4-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione Hydrochloride) showed limited intrinsic activity in α1, α4, and α6 containing receptors (Figure 3). At 1 mM the induced currents were less than 10% of the currents induced by the approximate EC100 GABA concentrations (Figure 4). In contrast, on α2, α3, and α5 containing receptors, 1 mM 5a caused currents of 17 ± 1%, 18 ± 2%, and 34 ± 3% of the maximal GABA-induced currents. On the same receptors 1 mM 6a induced currents that were 23 ± 5%, 13 ± 2%, and 48 ± 4% of the maximal GABA-induced currents.

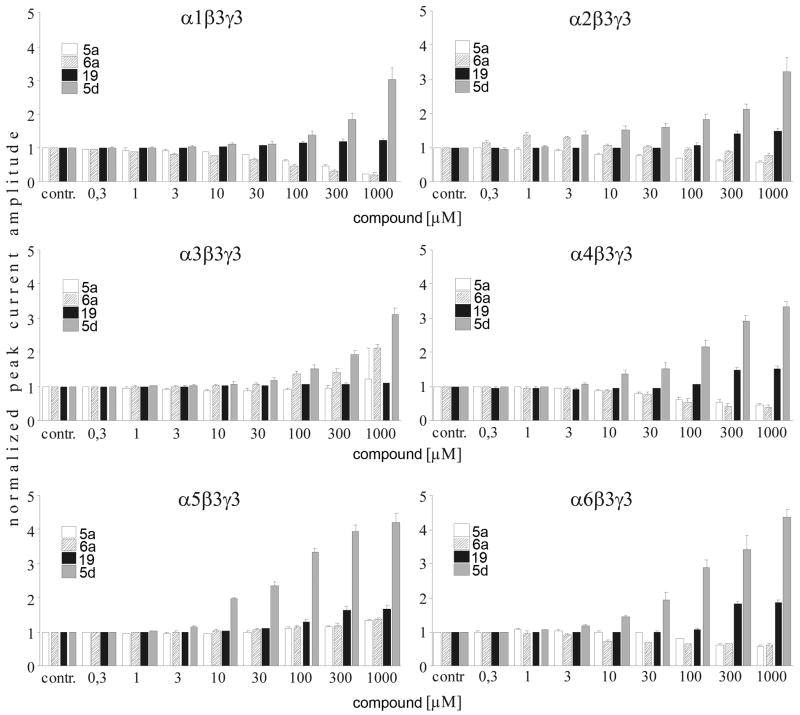

Figure 3.

Whole-cell recordings of HEK 293 cells expressing recombinant rat αiβ3γ2 (i = 1–6) GABAA receptors. Currents were normalized to the maximally GABA-induced current at the approximate EC100. To test the intrinsic activity, different concentrations of the 5-(4-piperidyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-derivates tested were applied to the cells. Error bars indicate the S.E.M for at least four cells.

Figure 4.

Whole-cell recordings of HEK 293 cells expressing recombinant rat αiβ3γ2 (i = 1–6) GABAA receptors. Currents were normalized to the GABA concentrations specific for the receptor subtype under in vitro conditions. Different concentrations of the 5-(4-piperidyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-derivates tested were co-applied with GABA concentrations around the EC25. Error bars indicate the S.E.M for at least four cells.

5d (5-Aminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one hydrochloride) induced desensitizing currents in all GABAA receptor combinations tested in a dose-dependent manner with an efficacy >50% of the maximal GABA-induced currents and an α subunit specific potency (Table 4, Figure 3). Receptors containing α6 subunits were most sensitive with an EC50 of 30 μM and receptors containing the α3 subunit were the least sensitive with a 5d EC50 of ca. 2300 μM.

Table 4.

Maximal intrinsic activity of 1 mM 5d normalized to the approximate maximal GABA-induced current (I/ImaxGABA) and the 5d EC50 and Hill coefficient on αiβ3γ2 (i=1–6) GABAA receptors. Data are means ± S.E.M.

| αsubunit | I/ImaxGABA | EC50 [μM] | Hill |

|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 280 ± 17 | 0.99 ± 0.05 |

| α2 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 182* | 1.23* |

| α3 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 2300* | 0.81* |

| α4 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 128 ± 8 | 1.56 ± 0.11 |

| α5 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 137 ± 14 | 1.31 ± 0.12 |

| α6 | 1.03 ± 0.01 | 30 ± 3 | 1.41 ± 0.14 |

marks values of an extrapolated dose-response curve.

The ability of 19 (4-(5-Methyl-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-yl)-piperidine hydrochloride) to directly activate GABAA receptors was restricted to α6 containing receptors where it induced currents 29 ± 4% of the maximal GABA-evoked currents. With all of the other α subunits 1 mM 19 induced a current less than 10% of the maximal GABA-induced current.

GABA modulatory effect

5a showed a slight dose-dependent potentiating effect on α3 and α5 containing GABAA receptors with maximal current potentiation by 1 mM 5a of 22 ± 11% for α3 and 34 ±5% for α5 containing receptors (Figure 4). In all other α subunits its action was antagonistic on GABA-induced currents with similar potency. Its antagonistic efficacy was highest in α1 containing receptors where 1 mM 5a inhibited GABA-induced current by 77 ± 3%. At this concentration 5a inhibited GABA-induced currents of other α subunits by 42 ± 2% for α2, 52 ± 5% for α4, and 41 ± 4% for α6.

6a (5-Piperidin-4-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione hydrochloride), the thio-derivative of 5a, had similar effects to 5a except on α2 containing receptors. 6a potentiated GABA-induced currents in α5β3γ2 receptors to an extent similar to that described for 5a, but on α3β3γ2 receptors the potentiating effect of 6a was higher with a current potentiation of 114 ± 8% at 1 mM. In contrast to 5a, in α2-containing receptors, low concentrations of 6a potentiated submaximal GABA-induced currents with maximal potentiation of 39 ± 4% at 1 μM. Whereas at 1 mM, 6a inhibited GABA currents by 24 ± 9%. 6a also inhibited GABA-induced currents in α1, α4, and α6 containing receptors.

5d(5-Aminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one hydrochloride), potentiated the GABA-induced currents for all of the α subunit isoforms with similar potency, apparent EC50 values ranged between 100 and 300 μM (Figure 3). The efficacy was similar in α1, α2, α3, and α4 containing receptors with current potentiation of 302 ± 35%, 324 ± 40%, 311 ± 18%, and 334 ± 13% at 1 mM, respectively. The 5d efficacy was significantly enhanced in receptors comprising α5 (423 ± 25%) and α6 (437 ± 21%) subunits with p of <0.01 in a two-sided t-test compared to α1 containing receptors.

Lastly, we analyzed the GABAA receptor α subunit specificity of 19 (4-(5-methyl-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-yl)-piperidine hydrochloride) and its hydrobromide with electrophysiological methods. This novel compound increased the GABA-induced currents in all GABAA receptor combinations tested with similar potency. The efficacy shows a slight subtype specificity which could be divided into two significantly different groups with p of <0.01 in a two-sided t-test. The group with higher efficacy consisting of α2, α4, α5, and α6 with positive modulation of the GABA-induced currents ranging from 48% in α2 to 87% in α6 at 1 mM 19. The positive modulation efficacy was smaller for α3 and α1 containing receptors where compound 19 potentiated the GABA-induced currents by 11% ± 2 and by 21% ± 5, respectively.

Two-Electrode Voltage Clamp Electrophysiology in Xenopus laevis oocytes

Based on the diverse set of effects, potentiation, inhibition and direct activation, seen with the compounds we sought to demonstrate that they bound in the GABA binding site. These experiments focused on compound 6a. We used a series of cysteine-substitution mutants in the GABA binding site.

Determination of GABA EC50 values

GABA dose-response relationships were determined for wild type and mutant α1β2 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Table 5). Mutant α 1S68Cβ2 receptors had an EC50 value comparable to α1β2 wt receptors. In contrast, the EC50 values for the mutants α1T129Cβ2, α1F64Cβ2 and α1R66Cβ2 were increased 14-fold, 43-fold and 554-fold, respectively, compared to wild type, in agreement with previously published data 46, 47.

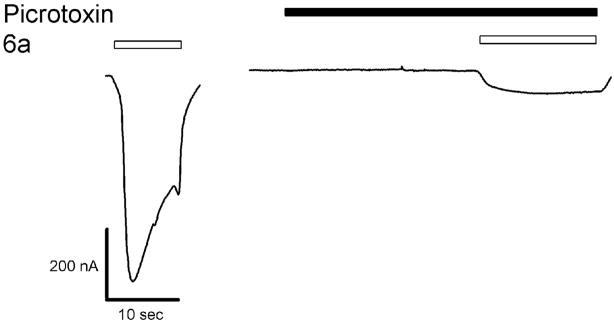

Determination of 6a EC50

6a acted as an agonist on α1β2 wt, α1F64Cβ2, and α1S68Cβ2 receptors. To prove that the 6a-induced currents were mediated by GABAA receptor activation we tested the ability of picrotoxinin, an open channel blocker, to inhibit the 6a induced currents. Co-application of 100 μM picrotoxinin and 10 mM 6a inhibited 6a-induced currents by 80–90% (Figure 5). We infer that 6a directly activates GABAA receptors.

Figure 5.

Picrotoxinin blocks 6a induced currents in α1β2 wt receptors. The first trace shows a 6a induced current. The second trace was recorded during a 20 s application of picrotoxinin, immediately followed by a co-application of 6a and picrotoxinin.

We determined the 6a EC50 for the Cys-substitution mutant receptors (Table 5). For wt receptors the 6a EC50 was 9.5 mM. It was similar for α1S68Cβ2. For α1F64Cβ2, the 6a EC50 was 0.6 fold less than for wt.

The efficacy of 6a as compared to GABA was significantly greater for α1F64Cβ2 receptors compared to α1β2 wt and α1S68Cβ2. A 30 mM concentration of 6a produced currents that were 60, 20, and 17% as large as the maximal GABA current for α1F64Cβ2, α1β2 wt, and α1S68Cβ2 receptors, respectively. Higher concentrations of 6a were not used due to the limited supply of the compound. The Hill coefficient of the 6a dose-response relationship was increased compared to GABA.

Determination of 6a IC50 values of the mutants

Co-application of 6a and GABA inhibited the GABA-induced currents. We performed competition experiments to determine the 6a IC50 for inhibiting GABA EC20 currents with α1β2 wt, α1F64Cβ2, and α1S68Cβ2 receptors (Table 5). One mM 6a inhibited the EC20 GABA current by more than 90% in these receptors. The residual GABA currents observed during the co-application of 1 mM 6a and GABA EC20 concentration, were 6.8 ± 1.0% (n = 4) for α1β2 wt, 9.0 ± 2.0% (n = 3) for α1F64Cβ2, and 3.0 ± 1.8% (n = 6) for α1S68Cβ2. Since the 6a-GABA competition experiments were done at a relatively low GABA concentration we decided that for the protection experiments the 6a concentration should be at least 1 mM.

Effects of MTS-reagents on the cysteine mutants and reaction rates

Methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents react 109 times faster with ionized thiolates (S−) than with thiols (SH) 51; thus, they are much more likely to react with water-accessible cysteine, which can ionize. We monitored the MTS reaction with a substituted cysteine by its affect on the channel’s macroscopic currents.

Application of the anionic reagent MTS-ethylsulfonate (MTSES−) did not affect the GABA current in α1β2 wt receptors (data not shown) 46. After complete reaction with MTSES− and/or MTSEA-biotin, subsequent GABA EC50 currents were inhibited to a similar extent for α1F64Cβ2, α1R66Cβ2, α1S68Cβ2 and α1T129Cβ2 receptors (see Table 6). We infer that in the cysteine-substitution mutants, changes in the GABA-induced current after MTS application were due to the covalent modification of the engineered cysteine.

Table 6.

Extent of inhibition of GABA-induced currents after reaction with MTS reagent.

| α1F64C | α1R66C | α1S68C | α1T129C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTSES− | 89 ± 3 (4) | 62 ± 3 (4) | 60 ± 10 (3) | n. d. |

| MTSEA-biotin | n. d. | 75 ± 4 (9) | n. d. | 60 ± 3 (6) |

Inhibition (% ± S.E.M. (n)) for GABA EC50 currents after complete reaction with MTSES− and MTSEA-biotin on GABAA receptors containing the cited cys-engineered α1 subunit together with the β2 subunit expressed in Xenopus oocytes. n.d. = not determined.

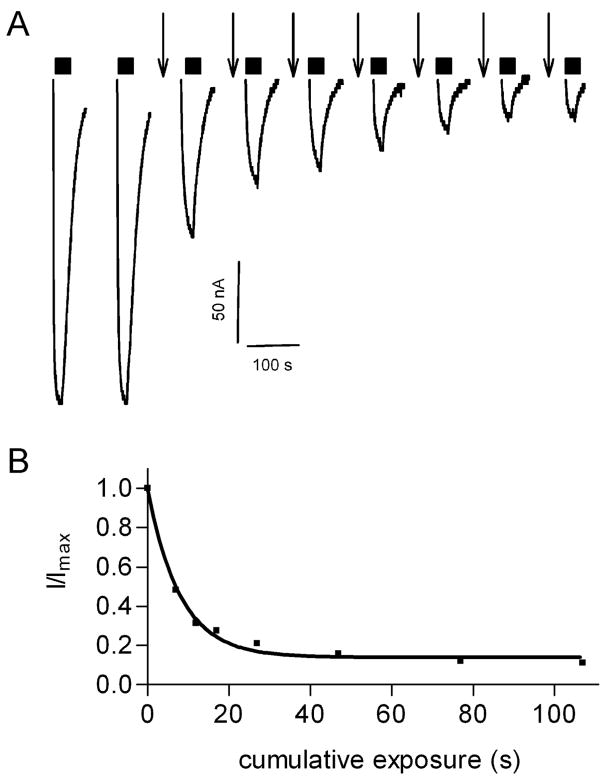

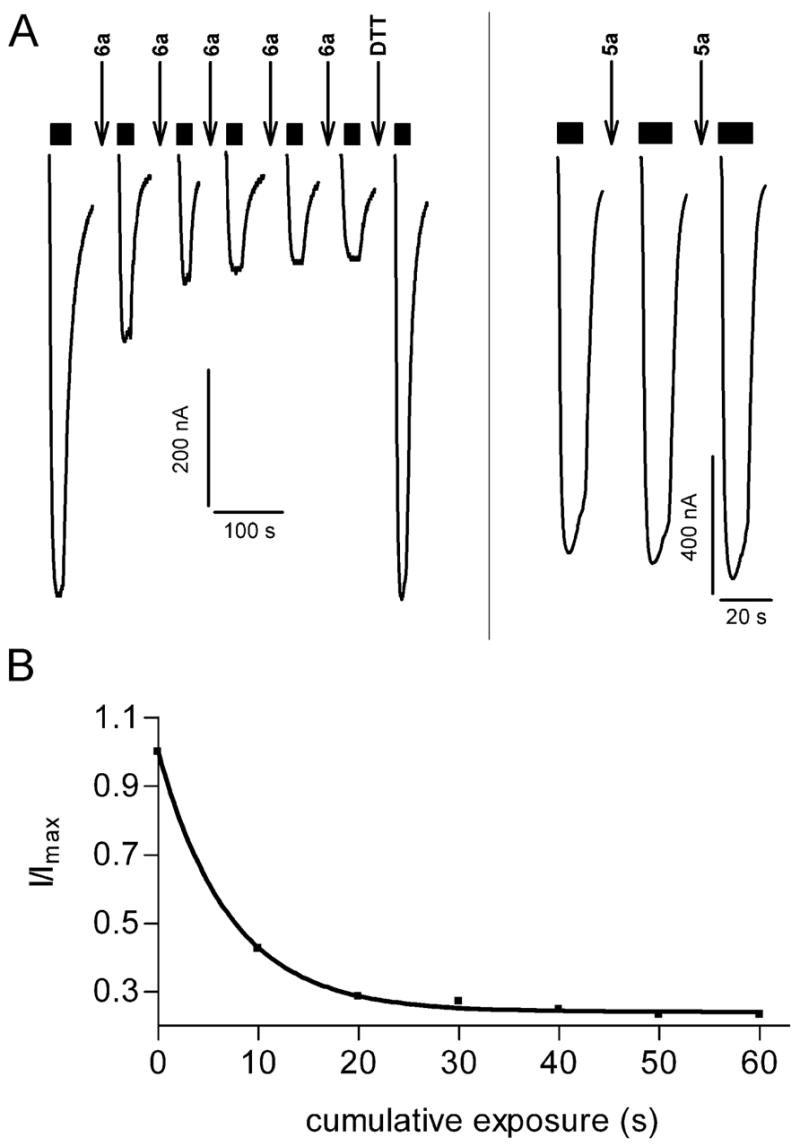

The observed second-order rate constants for reaction with MTSES− were 11300 ± 700 M−1/s for α1F64Cβ2, 48 ± 7 M−1/s for α1R66Cβ2, and 240 ± 40 M−1/s for α1S68Cβ2, which are in agreement with previously reported results (Table 7, Figure 6) 46. For α1R66Cβ2 and α1T129Cβ2 the second-order reaction rate constant for MTSEA-biotin with α1R66Cβ2 was 5500 ± 1600 M−1/s and with α1T129Cβ2 was 6,700,000 ± 1,100,000 M−1/s (Table 6). All reaction rates were well fit by a mono-exponential function. For each mutant receptor, however, there are two engineered cysteine residues, because αβ-receptors are pentameric and their subunit stoichiometry is proposed to be 2α:3β 52, 53. Either the two cysteine residues from each receptor reacted at the same rate, or reaction at only one residue gave the complete effect. These two possibilities are indistinguishable with the present methods.

Table 7.

MTS-reagent reaction rates.

| Receptor | MTS-reagent | Reaction Rate [M−1/s] | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| α1F64C β2 | MTSES− | 11,300 ± 700 | 3 |

| α1R66C β2 | MTSES− | 48 ± 7 | 5 |

| MTSEA-biotin | 5500 ± 1600 | 6 | |

| α1S68C β2 | MTSES− | 240 ± 40 | 4 |

| α1T129C β2 | MTSEA-biotin | 6,700,000 ± 1,100,000 | 3 |

Figure 6.

MTSES− reaction rate with the α1F64Cβ2 cysteine mutant. A, EC50 GABA current traces were recorded initially and after each brief application of 10 μM MTSES− (↓). Currents during MTSES−application (↓) are not shown. B, GABA test currents were normalized to the initial GABA current (Imax) and plotted versus cumulative MTSES− exposure time. Data were fit to a monoexponential decay function.

Protection of cysteine mutants by GABA and 6a

If an engineered cysteine forms part of a ligand-binding site, then the presence of the ligand in the binding site should reduce the ability of MTS reagents to react with the cysteine. This should decrease the measured MTS reaction rate in the presence of the ligand. It was reported previously that in the presence of GABA α1F64C, α1R66C, and α1S68C are protected from reaction with MTS reagents (MTSEA-biotin, MTSES−, MTSEA+) 46, 47. This protection may be due either to direct steric protection due to the presence of GABA in the binding site or to a GABA-induced conformational change reducing the accessibility of these residues to the MTS reagent. The fact that these cysteine mutants were also protected from modification by SR-95531, a competitive antagonist, implies that the mechanism of protection is a steric not an allosteric one 46, 47.

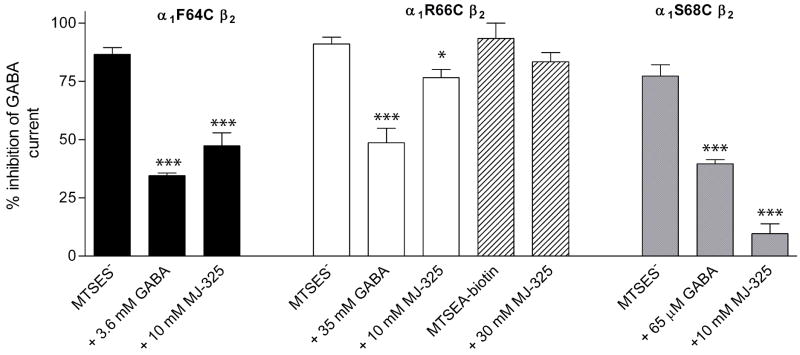

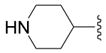

α1F64Cβ2 and α1S68Cβ2 receptors were protected from reaction with MTSES− by both GABA and 6a (Figure 7 and 8). In control experiments with α1F64Cβ2, a 12 s application of 10 μM MTSES− caused an 87 ± 3% (n = 4) reduction in subsequent GABA EC50 test currents (Figure 7A). In contrast, a 12 s co-application of 10 μM MTSES− with 3.6 mM GABA caused only a 35 ± 1% (n = 5) reduction of the subsequent GABA-induced currents (Figure 7B) and co-application of 10 μM MTSES− with 10 mM 6a resulted in only a 47 ± 6% (n = 4) reduction (Figure 7C) of the subsequent GABA-induced currents. Thus, the extent to which MTSES− could react with α1F64Cβ2 was reduced by the presence of GABA and 6a. This implies that both agonists protected the engineered cysteine from covalent modification.

Figure 7.

Protection assay shows that GABA and 6a protect α1F64Cβ2 receptors from reaction with MTSES−. A, MTSES− modification of α1F64Cβ2 in the absence of agonist. Two GABA test pulses were applied to demonstrate the stability of the GABA current. At the downward arrow marked MTSESnon-sat 10 μM MTSES− was applied for 12 s. Following washout a GABA test pulse was recorded. The GABA test current (third trace) was reduced by 87%. At the downward arrow marked MTSESsat 20 μM MTSES− was applied for 50 s to bring the MTSES− reaction to completion. Following washout a final GABA test pulse (fourth trace) was applied. Currents during MTSES− applications (↓) are not shown. B, GABA protects α1F64Cβ2 from modification by MTSES−. The same series of reagents are applied as in panel A, except that the MTSESnon-sat was coapplied with 3.6 mM GABA. The GABA current elicited by the next GABA test pulse (middle trace) is significantly larger than the GABA current after the MTSESnon-sat application in panel A, indicating that the presence of GABA significantly reduced the extent of reaction with the non-saturating concentration of MTSES−. C, 6a protects α1F64Cβ2 from modification by MTSES−. The same series of reagents are applied as in panel A, except that the MTSESnon-sat was coapplied with 10 mM 6a. The GABA current elicited by the next GABA test pulse (middle trace) is significantly larger than the GABA current after the MTSESnon-sat application in panel A, indicating that the presence of 6a significantly reduced the extent of reaction with the non-saturating concentration of MTSES−. Currents during MTSES− application (↓) with or without agonist are not shown. Duration of application of GABA EC50 test pulses are indicated by black horizontal bars above the current traces.

Similarly for the α1S68Cβ2 mutant, application of 450 μM MTSES− for 12 s reduced the subsequent GABA test currents by 77 ± 5% (n = 4) (Figure 8). Co-application of 450 μM MTSES− with 65 μM GABA or 10 mM 6a only reduced the subsequent GABA test currents by 40 ± 2% (n = 4) and 10 ± 4% (n = 4), respectively, consistent with protection of the α1S68C cysteine residue.

Figure 8.

Summary of the protection assay with α1F64Cβ2 (black bars), α1R66Cβ2 (clear and striped bars), and α1S68Cβ2 (grey bars). Bars indicate the average percent inhibition of GABA test currents following the application of a non-saturating concentration of MTSES− either in the absence of agonist or in the presence of EC90 GABA or 6a (10 or 30 mM). We infer that a reagent, GABA or 6a, protected a mutant from reaction with MTSES− if the extent of inhibition by MTSES− coapplied with either GABA or 6a is significantly less than the extent of inhibition by MTSES− applied alone. Conditions where the co-application of GABA or 6a are significantly different than the effect of MTSES− application alone are indicated by *; (*, P<0.014; ***, P<0.0001) by one way ANOVA and Fisher’s PLSD. For α1R66Cβ2 30 μM MTSEA-biotin reduced the subsequent GABA test currents by 93%. Application of 30 μM MTSEA-biotin with 30 mM 6a reduced the subsequent GABA test currents by 83%. The limited supply of 6a precluded further experiments.

In similar experiments with α1R66Cβ2 receptors, 10 mM 6a demonstrated slight, but significant protection of the engineered cysteine from reaction with MTSES− (Figure 8). A 12 s application of 2 mM MTSES− to α1R66Cβ2 inhibited 91 ± 3% (n = 6) of the subsequent GABA EC50 current. Co-application of 35 mM GABA with MTSES− inhibited 49 ± 6% (n = 3) of the subsequent test currents, consistent with protection by GABA. In contrast, application of 10 mM 6a with 2 mM MTSES− resulted in 77 ± 4% (n = 5) inhibition of the subsequent GABA test currents. Comparable results were obtained for MTSEA-biotin, application of 30 mM 6a with MTSEA-biotin resulted in 79 and 87% (n = 2) inhibition of the subsequent GABA test currents as compared to 87 and 100% (n = 2) inhibition in control experiments. For α1R66C the results of the protection experiments are complicated by the fact that 6a reacts with α1R66Cβ2 as described below.

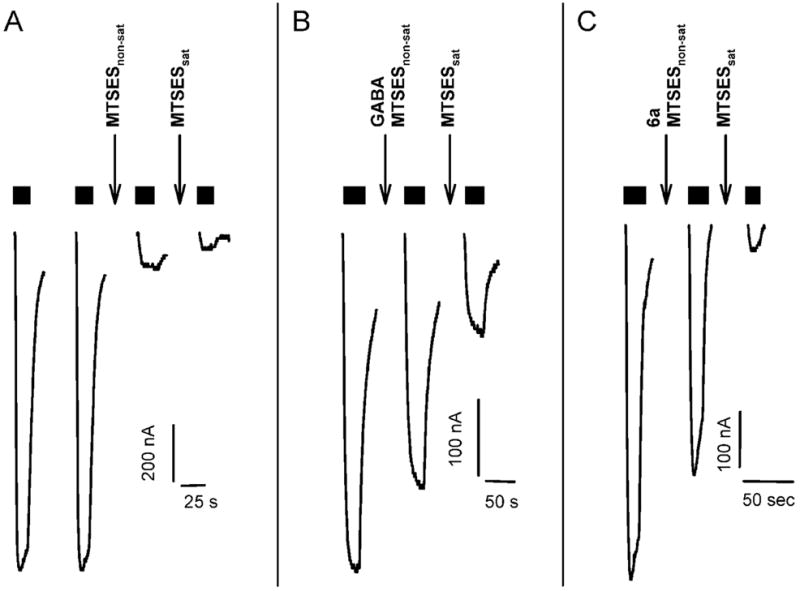

6a reacts with the engineered cysteine in α1R66Cβ2 receptors

To our surprise, while examining competition between GABA and 6a on α1R66Cβ2 receptors, we noted that once the oocytes showed stable GABA test responses, co-application of GABA and 6a irreversibly reduced the subsequent GABA test currents (data not shown). Alternating between GABA and 6a resulted in a progressive decline in the GABA test currents that finally led to a stable GABA current that was significantly lower, 68 ± 4% (n = 4), than the initial GABA test current (Figure 9A). At this stage, application of MTSES− caused no further effect. In contrast, application of MTSES− to α1R66Cβ2 expressing oocytes untreated with 6a produced 62 ± 3% (n = 4) inhibition of GABA currents. Furthermore, the GABA currents after either 6a or MTSES− application could be recovered by application of the reducing agent DTT (10 mM, 20 s) (Figure 9A). Theoretically, oxadiazole-2-thiones, such as 6a, can exist in two tautomeric forms, the thio-amide (thione) form and the imino-thiol form. IR, UV and NMR spectra indicate that they do exist predominantly in their thione-form 50. However, the ability to form the thiol-tautomer enables the oxadiazole-2-thione to form a disulfide bond. Consistent with the idea of the formation of a stable disulfide bond, repeated 10 s applications of 30 mM 5a, a 6a analogue with an oxygen in place of the potentially sulfhydryl reactive oxadiazolethione sulfur moiety, did not irreversible alter the subsequent GABA currents in α1R66Cβ2 expressing oocytes (Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

6a reacted with α1R66Cβ2. A, Currents recorded from an oocyte expressing α1R66Cβ2. Alternating 10-s applications of 30 mM 6a [indicated by (↓)] and 5.5 mM GABA test currents (bars above current traces) resulted in a progressive decrease in the GABA test currents. The decrease eventually plateaued at which time a 12-s application of 10 mM MTSES− (↓) had no effect indicating that all accessible cysteine had reacted with 6a. Reduction by a 20-s application of 10 mM DTT (↓) led to complete recovery of the GABA test current magnitude. Currents during application of 6a, MTSES− and DTT are not shown. B, Application of the oxygen analogue 5a (30 mM, 10 s) (↓) to an oocyte expressing α1R66Cβ2 did not decrease the subsequent GABA test currents. Currents during 5a application are not shown. C, Reaction rate of 6a with α1R66Cβ2. GABA test currents were normalized to the initial GABA test current, plotted as a function of cumulative duration of 6a application and fitted to a monoexponential decay function.

In order to measure the reaction rate of 6a with α1R66C we alternately applied 5.5 mM GABA and 6a to oocytes until the GABA currents no longer declined (Figure 9A). The decline in the α1R66Cβ2 GABA currents as a function of the cumulative 6a exposure time could be fit with a single exponential decay function. 6a second-order reaction rate with the engineered cysteine in α1R66C was 5 ± 1 M−1/s (n = 3) (Figure 9A, C). The second-order reaction rate constant was independent of the 6a concentration used (either 10 or 30 mM).

In our homology model based on the AChBP structure the α1 subunit residues R66 and T129 are in close proximity but on adjacent β-strands. Based on protection with agonist and antagonist SCAM analysis predicts that α1T129 lines the binding pocket 48. A 2-min application of 5 mM MTSES− reduced the subsequent currents elicited by GABA EC50 test pulses in α1T129Cβ2 by 63 ± 5% (n = 3). We tested whether 6a would react with α1T129C. Alternate application of EC50 GABA and 30 mM 6a did not lead to a change in GABA EC50 peak currents in α1T129Cβ2, α1F64Cβ2, or α1S68Cβ2 containing receptors, suggesting that the reaction of 6a with α1R66C is highly specific. It should be noted that the MTSES− reaction rate with α1R66C was at least 5-fold slower than with any of the other cysteine mutants used in this study (Table 6). It was orders of magnitude slower than the reaction rate with α1T129C. Thus, the lack of 6a reaction with the other cysteine mutants is not due to lower intrinsic reactivity of those positions.

Discussion

Structure-Activity relationships of 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-ones

The 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-one compound with the highest affinity as measured by inhibiting muscimol binding is the aminomethyl-derivative 5d with IC50 values of 1.4 μM and 1.1 μM against rat cortex and cerebellum, respectively. The homo-derivative 5g with its 2-aminoethyl side chain displayed seven times higher IC50 values. The conversion of the primary amine function of 5d to a secondary methylaminomethyl group in 5e caused a significant decrease in affinity and the tertiary dimethylaminomethyl compound 9c showed negligible capacity to displace [3H]muscimol. Thus, the affinity among the 5-aminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-ones decreases from the primary aminomethyl 5d over the secondary methylaminomethyl 5g to the tertiary dimethylaminomethyl 9c. We infer that the amino group is involved in interactions with the binding site because the cyclohexyl- 9d and methyl 9e substituted oxadiazol-2-ones that lack an amino group do not show significant inhibition of muscimol binding.

An additional steric demand at the methylene group of the aminomethyl compound 5d that led to the 1-aminoethyl derivative 5f was not well tolerated, i.e., the methyl group in 5f led to a significant decrease in the ability to displace [3H]muscimol. The 2-pyrrolidine compound 5c, which can be considered as a bridged aminomethyl derivative of 5d, showed an almost complete loss of affinity. In 5c the inhibition reducing effects of a secondary amine function and a steric strain added to the methylene group are combined. Similarly, when the 2-aminoethyl sidechain was incorporated into a 3-piperidyl ring as in 5b, the compound was inactive. However, the 4-piperidyl compound 5a, was active although the IC50 was increased by a factor of four when compared to the 2-aminoethyl compound 5g. Thus, the affinity appears to be sensitive to the position of the amino group because when it is at the 4 position in the piperidyl ring as in 5a the IC50 was 183 μM but when located at the 3 position in 5b the affinity was negligible. Furthermore, derivatives of the 4-piperidyl amino group leading to tertiary amines in the form of the N-benzyl-piperidine 9b or the N-methyl-piperidine 9a, showed weak activity in this assay. This is consistent with the loss of activity as the amino group transits from a primary to secondary to tertiary amino group.

Structure-Activity relationships of 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-thiones

The 4-piperidyl derivative 6a showed an IC50 comparable to the aminomethyl derivative 6d. This is in contrast to the oxadiazolones where the aminomethyl derivative showed a 40 times lower IC50 than the 4-piperidyl derivative. The aminoethyl derivative 6g showed the third highest degree of inhibition in the thione series. However, when the aminomethyl or aminoethyl was bridged in the thione series to obtain a 2-pyrrolidinyl 6c or 3-piperidinyl 6b compound a significant amount of affinity was still retained. This is also different from the oxadiazolones where the corresponding modifications were not tolerated. Another difference was found when comparing the primary, secondary and tertiary aminomethyl compounds. Here the primary aminomethyl 6d had a higher affinity than the dimethylaminomethyl compound 10c which in turn had a higher affinity than the methylaminomethyl compound 6e. This decline in affinity seems to be correlated to the basicity. We infer that the amine-N interacts with the protein. Other side chains that resulted in a weak affinity are the compounds with the 4-(N-methyl-piperidinyl) 10a and the 4-(N-benzyl-piperidinyl) 10b moiety. Again the cyclohexyl- and methyl substituted oxadiazol-2-thiones 10d and 10e did not show a significant inhibition of muscimol binding.

Structure-activity relationships of modifications to the 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-one ring itself

As mentioned above, substituting the 2-one oxygen with sulfur did not have a uniform effect. Depending on the amine-side chain in position 5 of the heterocycle the sulfur bearing compound exhibited lower (4-piperidinyl, 6a < 5a; 3-piperidinyl, 6b < 5b; 2-pyrrolidinyl, 6c < 5c) or higher IC50 values (aminomethyl, 6d > 5d; 2-aminoethyl, 6g > 5g; methylaminomethyl, 6e > 5e) than their oxygen bearing counterparts. For other side chains there was no difference in affinity detected between -thione and -one (N-methyl-piperidine, 9a = 10a; N-benzyl-piperidine, 9b = 10b). The 4-piperidinyl series 5a, 6a, 19 showed, that the hydrogens of the oxadiazol-2-one/oxadiazol-2-thione 3-nitrogen or of the tautomeric oxadiazol-2-ol/oxadiazol-2-thiol 2-alcohol/2 thioalcohol oxygen/sulfur are unlikely to be directly involved in hydrogen-bonding, nor, in their deprotonated form, in ion-ion or ion-π interactions, since the 2-methyl-1,3,4-oxadiazole showed intermediate affinity. Moreover, we infer that the heteroatoms in the 1,3,4-oxadiazol ring act as hydrogen-bond acceptors when interacting with amino acids in the binding site. However, the drop in affinity from 6a over 19 to 5a followed the decrease in volume of the 2-substituent of the 1,3,4-oxadiazol (sulfur > CH3 > oxygen). The compound with the smallest substituent (hydrogen) at position 2 of the 1,3,4-oxadiazol 11 showed a complete loss of affinity opposite to the derivatives with an oxygen 9b or sulfur 10b, again indicating that some bulk at the 2-position is necessary.

The 1,2,4-triazoles explore the effect of substituting the oxygen at position 1 of the 1,3,4-oxadiazol-ones/thiones with a benzyl substituted nitrogen. This exchange was not tolerated at all in the aminomethyl compound: the triazole 16d completely lost its affinity in contrast to the 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-one, whereas the 4-piperidinyl triazole 16a showed a reduced but still significant displacement of [3H]muscimol. The difference in tolerance of bulk at this position of the heterocyclic half of the compounds might indicate that the longer piperidine derivatives share the binding partners for the side chain amino-N with the shorter ligands, but bridge to different amino acids of the binding site with the heterocyclic portion of the molecule. This difference in coordination might account for the difference in tolerance for bulky substituents.

Comparison with previous 4-PIOL derivatives

Frølund and colleagues have reported on the synthesis and evaluation of 4-PIOL derivatives as GABA partial agonists or antagonists. They mainly investigated the influence of substituents at position 4 of the 3-isoxazolol ring39, 54. In these studies, small aliphatic and also bulky aromatic substituents were tolerated. 4-PIOL derivatives in these investigations had a Ki between 0.049 and 10 μM as compared to 4-PIOL with 9.1 μM and our best derivatives with an IC50 between 1 and 183 μM. Methyl or ethyl substitution of 4-PIOL lead to compounds that retained some agonistic activity with the binding affinity as determined by [3H]muscimol binding assays being retained as well, whereas the bulky substituents did not show agonistic activity but their affinity was increased in the binding assays. In the context of the 1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-ol moiety used in the present study, substitution of the oxygen at position 1 with a benzyl substituted nitrogen did not improve affinity as 16a had a somewhat lower affinity than 5a. We infer that the large cavity that has been suggested to accommodate the aromatic residues of the 4-subsituted 4-PIOL derivatives, is not available for compounds of our series, possibly because the 1,3,4-triazol-2-ol derivatives are not arranged in a way that would align the aromatic moiety with the hydrophobic pocket. It is likely that the occupancy of this cavity by the aromatic substituted 4-PIOL derivatives prevents the binding site closure which has been proposed to be an early step in the conformational change linking ligand binding to channel gating.

It has been observed previously that the exchange of an oxygen in the small carboxyl group bioisosteric ring by a sulfur can have different effects: the sulfur analogue of 4-PIOL has a higher affinity than 4-PIOL, whereas the sulfur analogue of THIP has a lower affinity than the oxygen containing counterpart40, 54, 55. The conclusion was that the 3-isoxazolol heterocycles of 4-PIOL and THIP are not at identical positions in the binding sites. Further results demonstrated that the flexible side chain of the arginine R66 in the α1 subunit might enable the binding pocket to adapt to different bioactive conformations of ligands54.

α-subunit specificity

The electrophysiological characterization of the most active compounds was divided in investigating the agonistic potency of individual compounds and determining their modulating effect on GABA-induced currents. The agonistic profiling yielded 5d as the most active compound. This compound had an EC50 comparable to the GABA EC50 at all α1–6β3γ2 subunit combinations, ranging between from 30 μM for α6 to 1 mM for α3-containing receptors. In the GABA current modulating assay 5d showed potentiating effects at all subunit combinations reflecting its pure agonistic character. We assume that the small 5d compound can be accommodated in all binding sites irrespective of the specific α subunit where its orientation and size allow complete agonist-induced contraction of the binding site and subsequent gating in a manner comparable to the GABA induced effect. Increasing the spacer that bridges the basic amino function from the oxadiazolol moiety from a methylene group in 5d to a piperidine ring in 5a converts the compound from an unselective agonist into an antagonist at α1, α4, and α6 containing receptors and a weak partial agonist at α2, α3 and α5 containing receptors. The intrinsic activity is highest at α5 containing receptors. The thio derivative of 5a, 6a, showed a comparable profile, with the exception that at α2 containing receptors it is potentiating GABA currents at low concentrations while it is inhibitory at higher concentrations. The methyl derivative 19 was only agonistic at α6 receptors, while it showed slight potentiating effects at high concentrations at α2, α4, α5 and α6 containing receptors.

6a binds in the GABA binding site

Numerous drugs modulate and directly activate GABAA receptors often by binding to sites other than the GABA binding sites. Based on several lines of evidence we conclude that 6a binds within the GABA binding pocket. First, 6a protected α1F64C and α1S68C from modification by MTSES− (Fig. 7 and 8). These residues are located in the GABA binding site in a homology model based on the AChBP structure 49, 56–58. Czajkowski and coworkers previously showed that GABA protected the cysteine at α1F64C from modification by MTSES− but pentobarbital did not. Pentobarbital activates the receptor by binding at a site in the transmembrane domain. Thus, the lack of protection by pentobarbital argues that the protection induced by GABA is due to local steric effects of GABA and not due to conformational changes associated with gating 46, 47. Thus, we conclude that 6a protected α1F64C by its presence in the GABA binding site and not by conformational changes induced by 6a binding. Secondly, 6a specifically and covalently modified the neighboring cysteine-substitution mutant, α1R66C, inhibiting the subsequent GABA currents. This inhibition did not occur with 5a which has an oxygen in place of the thiol-reactive sulfur in 6a. Furthermore, following inhibition of α1R66C by reaction with 6a subsequent application of MTSES− had no effect, whereas, without 6a pretreatment, application of MTSES− would have inhibited the GABA-induced currents. Thus, MTSES− had no effect when it was applied after 6a because MTSES− cannot react with disulfide linked sulfurs. In contrast, the inhibition induced by 6a reaction was reversed by DTT application indicating that 6a formed a mixed disulfide bond with the cysteine thiol. Taken together, we infer that 6a binds in the GABA binding site.

The ability of 6a to protect α1S68C from modification by MTSES− provides insight into the conformational changes induced by 6a binding (Fig. 8). Both GABA and pentobarbital protected this cysteine mutant from MTSES− modification. Czajkowski and coworkers concluded that in the activated state conformation, access to this residue was reduced due to a conformational change of the binding site rather than by the presence of GABA in the binding site 59. We infer that in the region of α1S68 6a produces a similar conformational change to that induced by GABA and pentobarbital when it activates the receptor. This suggests that 6a induces a conformational change in the receptor similar to that induced by GABA binding.

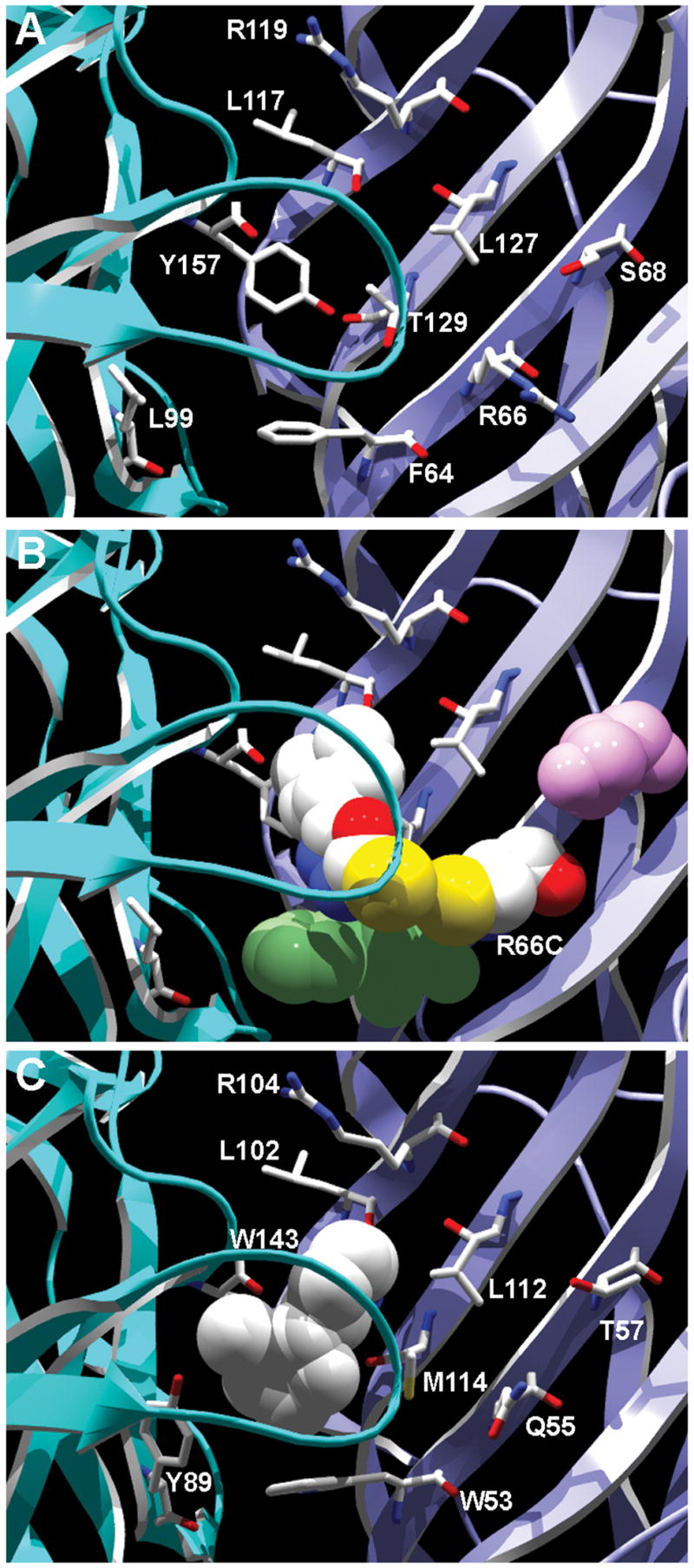

Further, the disulfide bond formation between 6a and the introduced cysteine at the α1R66 position provides insight into the orientation of 6a in the GABA binding site. The reaction between 6a and α1R66C appears to be specific because 6a did not react at a measurable rate with the cysteine substituted for the neighboring residues on the same β strand, α1F64 or α1S68, nor did it react with a cysteine at α1T129, the residue predicted to lie in closest proximity on the adjacent β strand. If all other factors were similar, the ratio of the reaction rates of 6a with the four cysteine mutants should be similar to the ratio of the reaction rates for the MTS reagents with these mutants. The MTS reagents reacted faster with α1F64C and α1S68C than with α1R66C (Table 6). Thus, it is surprising that 6a only reacted at a measurable rate with α1R66C. Since 6a is much less reactive than the MTS reagents the reason why this compound only reacts at this position must be attributed to a highly selective interaction of the 6a sulfur with the α1R66C sulfur. Therefore, we infer that the favorable orientation of 6a in the binding site brings the 6a sulfur into close proximity with the α1R66 position leading to the highly specific reaction. This establishes one point of contact between 6a and the complementary side of the binding site.

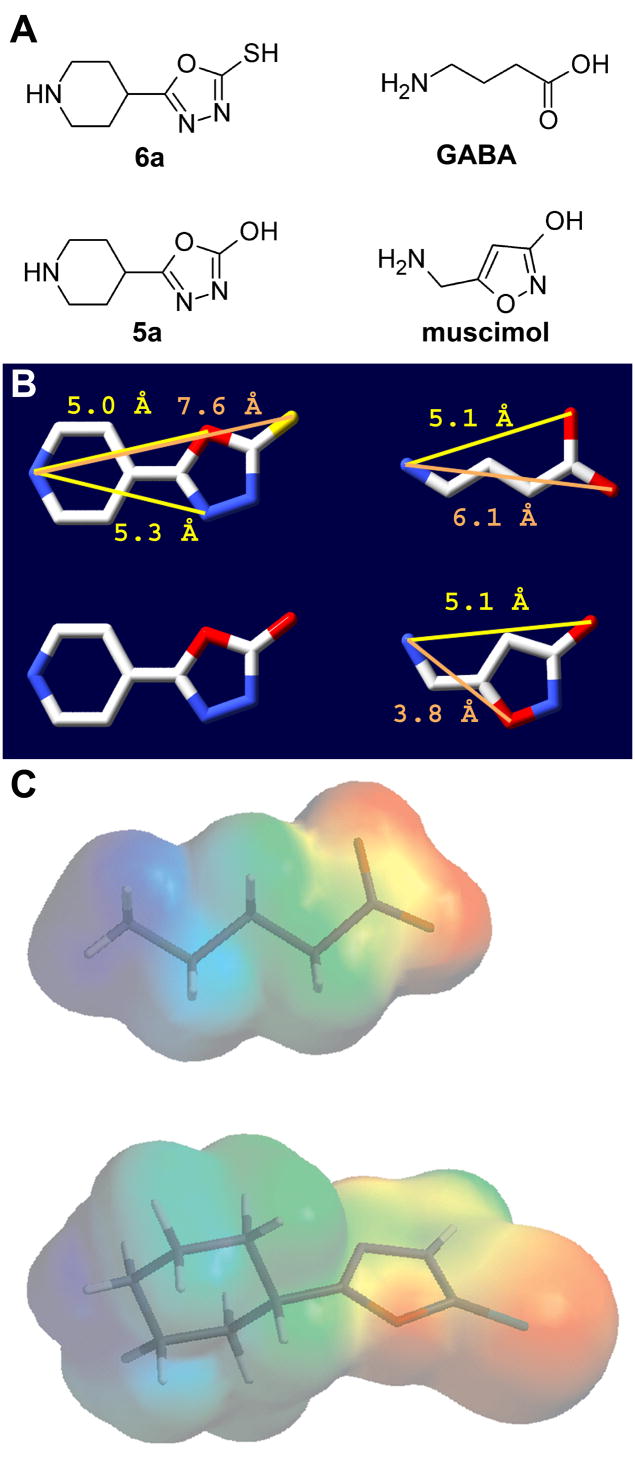

We assume that 6a bridges the principle and complementary sides of the binding site in a manner similar to GABA. We generated a model of the GABAA receptor β2-α1 interface based on the AChBP crystal structure with nicotine bound (Figure 10). 6a can fit into the binding site with its basic nitrogen superposed on the position of nicotine’s basic pyridine nitrogen in the principle side of the binding site and with the 6a sulfur in close proximity to the introduced α166C sulfur on the complementary side of the binding site (Figure 10B). The close proximity of the sulfurs may explain the high collision probability and consequently the reactivity necessary to form the disulfide bond between 6a and the engineered cysteine at position α1R66. This orientation in the binding site may explain why it is a weak agonist. In the AChBP crystal structure on the complementary side of the binding site, nicotine forms hydrogen bonds with backbone carbonyls and amides on the β strand containing the residue that aligns with α1T129 (Figure 10C). This β strand is adjacent to the α1R66-containing β strand. 6a is larger than GABA: the distance between the two potential H-bonding sites, i.e., the protonated positively charged nitrogen and the most distant high electron dense heteroatom O (GABA) and S (6a) (Figure 11 and 10), being 6.1 Å and 7.6 Å, respectively. Thus, GABA might only span the distance between the β-subunit principle site residues where the positively charged N is coordinated and the α1T129 β-strand of loop E (Figure 10A). In contrast, the larger 6a extends to the more distant β strand containing residue α1R66 (Figure 10B). Activation of the Cys-loop receptors may involve a contraction of the two halves of the binding site 59. Because 6a bridges to a different part of the complementary side of the binding site its ability to pull the two halves of the binding site together may be reduced compared to GABA resulting in 6a being a partial agonist. The idea that 6a is a partial agonist because it is less effective at closing the binding site is consistent with the conceptual model of partial agonism derived from structural studies of the ionotropic glutamate receptors 60.

Figure 10.

Homology model of the GABAA receptor agonist binding site based on the AChBP structure (PDB 1UW6). A, View of the principle side of the β2 subunit GABA binding site (light blue) and of the complementary side of the α1 subunit GABA binding site (dark blue) showing backbone in ribbon form. Side chains of residues mentioned in the text are shown in wireframe format. B, GABA binding site showing backbone in ribbon form with 6a and α1R66C shown in spacefilling format with CPK colors. The close proximity of the sulfurs (yellow) in 6a and α1Cys66 is consistent with the observed reaction between 6a and α1Cys66. α1F64 is shown in green spacefilling format. The close proximity between α1F64 and 6a is consistent with the steric protection of the cysteine substituted at this position. In contrast, α1S68 (pink colored spacefilling format) is not in close proximity to 6a. C, View of nicotine bound in the AChBP binding site (PDB 1UW6) from the same perspective as in panel B. Backbone is shown in ribbon form and nicotine in white-color spacefilling format. Side chains of AChBP residues aligned with the GABAA cysteine mutants discussed in the text and shown in panel C are in wireframe format. Nicotine interacts with the homologous β strand adjacent to the β strand containing the residue in this model aligned with GABAA α1R66.

Figure 11.

A, Structures of 6a and 5a (left column) and of GABA and muscimol (right column). B, Structures of the compounds in panel A with atomic distances between the basic nitrogen atom and other polar atoms in the respective molecules. Distances were measured after energy minimization (Chemsketch 5.12, ACD Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada). CPK color scheme used, carbon, white; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; sulfur, yellow. C, Electrostatic potential mapped onto the van der Waals surface of GABA (top) and 6a (bottom) with stick representation of molecules. Red indicates negative electrostatic potential and blue is positive potential. Image generated using Spartan. Note the similarity of the overall electrostatic potential, especially the distance between the positively charged nitrogen in GABA or 6a to the negative carboxylate (GABA) or the oxadiazolthione moeity (6a).

6a should not cover the α1 loop connecting L117 and L127 that harbors the four amino acids (ITED in α1) recently identified as α variant specific transducing elements rather than binding site elements 4. A trap-like motion of this loop, to an extent specified by these four amino acids in a given α isoform, could further explain the differences in GABA sensitivities between the GABAA receptor subtypes.

Conclusions

We synthesized a series of derivatives of 4-PIOL, a compound previously shown to be a weak GABAA partial agonist. We started by replacing the 3-isoxazolol moiety in 4-PIOL with a 1,3,5-oxadiazol-2-ol moiety to yield 5a. For the first time we describe GABAA receptor ligands with a 1,3,5-oxadiazol-2-ol as a carboxylic acid bio-isosteric group. Compound 5a was modified at different positions to investigate structure-activity relationships: the piperidine moiety was exchanged and modified, the substituent at the 2 position of the 1,3,5-oxadiazol-2-ol was varied, and the 1,3,5-oxadiazol-2-ol was exchanged by 1,2,4-triazol-5-ol.

The most active piperidine derivatives 5a and 6a were weak partial agonists that differentiated weakly between different α subunit containing receptors, whereas the small aminomethyl 5d showed a profile of a pure agonist that is very similar to GABA.

The described structure-activity relationships extend the currently available information for ligands of the agonist binding site of the GABAA receptor. Frølund et al. have shown previously how to convert 4-PIOL into pure antagonistic compounds while we now show how 4-PIOL can be modified to either obtain a pure or partial agonists with weak α subtype preferring profiles.

In addition, this study demonstrates that 6a binds in the GABA binding site, and that 6a is oriented in the binding site such that its interaction with the complementary portion of the binding site is displaced from the interaction site of nicotine and carbamylcholine in the AChBP structure. The later finding may explain why 6a is a partial agonist. Further investigations are necessary to determine if the two GABA binding sites are the only sites involved in the activity of this compound. These results coupled with GABA binding site homology models based on the AChBP structure may provide a foundation for rational design of GABAA receptor subtype-specific agonists with higher efficacy and specificity.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

Procedures and spectroscopic data for non-target compounds can be found in the supporting information.

General Procedures for the Removal of the Boc-group: Procedure F (Compounds 5a,c,e,f,g, 6c,d,e,f,g, 16a,d, 17a, 19)

The Boc-protected amine (1 equiv) was dissolved in a minimum amount of methanol and cooled in an ice-bath in a nitrogen atmosphere. After adding ethanolic HCl 2.3N (4.5 equiv) the mixture was allowed to reach room temperature and stirred overnight. Products were isolated by filtration in a nitrogen atmosphere, in some cases a precipitate was only formed after adding ethyl acetate (50–98%).

Procedure G (Compounds 5b,d, 6a,b, 19)

The Boc-protected amine was dissolved in ethyl acetate and cooled to −20 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere. Gaseous HCl was bubbled through the mixture for 5 min. The reaction was allowed to come to room temperature and stirred until a precipitate was formed. Products were isolated by filtration in a nitrogen atmosphere, or after removing the solvent and recrystallization in ethanol (56–88%).

5-Piperidin-4-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride. (5a)

Starting from 3a the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (98%); mp = 314 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.74–1.88 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.00–2.05 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.89–3.03 (m, 3H, 3CH), 3.21–3.25 (m, 2H, 2CH), 8.98–9.28 (m, 2H, NH2), 12.26 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 24.75 (CH2), 30.94 (CH), 42.07 (CH2), 155.11 (Cq), 158.08 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 169 (M+). Anal. (C7H11N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

5-Piperidin-3-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride. (5b)

Starting from 3b the compound was synthesized as described in procedure G. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue recrystallized from ethanol: white crystals (66%); mp = 207 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.60–1.85 (m, 3H, 3CH), 1.97–2.01 (m, 1H, 1CH), 2.82–2.91 (m, 1H, 1CH), 2.96–3.04 (m, 1H, 1CH), 3.13–3.19 (m, 2H, 2CH), 9.26 (m, 2H, NH2), 12.32 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 24.75 (CH2), 30.94 (CH), 42.07 (CH2), 155.11 (Cq), 158.08 (Cq); MS m/z 167 (M+-2 free base). Anal. (C7H11N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

L-5-Pyrrolidin-2-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride. (5c)

Starting from 3c the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (84%); mp = 199 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.88–2.05 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.12–2.30 (m, 2H, 2CH), 3.20–2.25 (m, 2H, CH), 4.63 (t, 7.75 Hz, 1H, CH), 10.13 (s, 2H, NH2), 12.72 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 23.77 (CH2), 27.18 (CH2), 45.56 (CH2), 52.88 (CH), 152.34 (Cq), 154.72 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 155 (M+ free base); [α]D = −3.9 ° (RT, c = 0.71, H2O). Anal. (C6H9N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

5-Aminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride. (5d)

Starting from 3d the compound was synthesized as described in procedure G. The product was separated by filtration after stirring a few minutes at room temperature: white crystals (88%); mp = 235 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.03 (s, 2H, CH2), 8.82 (s, 3H, CH2NH3), 12.71 (s, 1H, NH); EI-MS m/z 115 (M+ free base). Anal. (C3H5N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

5-Methylaminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride (5e)

Starting from 3e the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (79%); mp = 176 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.58 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.15 (s, 2H, CH2), 9.88 (s, 2H, NH2), 12.81 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 32.75 (CH2), 42.22 (CH3), 150.10 (Cq), 154.65 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 129 (M+ free base). Anal. (C4H7N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

D-5-(1-Amino-ethyl)-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride. (5f)

Starting from 3f the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (90%); mp = 194 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.47 (d, 6.86 Hz, 3H, CH3), 4.44 (q, 6.86 Hz, 1H, CH), 8.93 (2, 3H, NH3), 12.75 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 15.77 (CH3), 42.62 (CH2), 154.16 (Cq), 154.67 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 129 (M+ free base); [α]D = +7.0 ° (RT, c = 0.63, H2O). Anal. (C4H7N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

[5-(2-Amino-ethyl)-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride. (5g)

Starting from 3g the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (77%); mp = 206 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.89 (t, 6.60 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2NH3), 3.06 (t, 6.74 Hz, 1H, CH2CH2NH3), 8.23 (s, 3H, NH3), 12.25 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 24.49 (CH2), 35.37 (CH2), 153.97 (Cq), 155.27 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 129 (M+ free base). Anal. (C4H7N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

5-Piperidin-4-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione Hydrochloride. (6a)

Starting from 4a the compound was synthesized as described in procedure G (74%). The compound was also synthesized following procedure F. In this case 1/3 of methanol co-crystallized with 6a, which could be removed by solving the crystals in water, removing some of the solvent under vacuum at 20 °C and freeze drying the resulting solution (91%): white crystals; mp = 232 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.79–1.92 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.06–2.12 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.90–3.07 (m, 2H, 2CH), 3.15–3.28 (m, 3H, 3CH), 8.89–9.19 (m, 2H, NH2), 14.49 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 24.96 (CH2), 30.50 (CH), 42.01 (CH2), 165.04 (Cq), 177.93 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 185 (M+ free base). Anal. (C7H11N3OS·HCl) C, H, N, S.

5-Piperidin-3-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione Hydrochloride. (6b)

Starting from 4b the compound was synthesized as described in procedure G, with the exception that 10% of the solvent were ethanol. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue recrystallized in ethanol: slightly green crystals (58%); mp = 219 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.70–1.85 (m, 3H, 3CH), 2.00–2.10 (m, 1H, CH), 2.80–2,92 (m, 1H, CH), 3.04–3.19 (m, 2H, 2CH), 3.34–3.43 (m, 2H, CH), 9.20–9.60 (m, 2H, NH2), 14.55 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 20.75 (CH2), 24.88 (CH2), 30.82 (CH), 43.02 (CH2), 44.01 (CH2), 163.08 (Cq), 177.94 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 185 (M+ free base). Anal. (C7H11N3OS·HCl·1/3H2O) C, H, N, S.

L-5-Pyrrolidin-2-yl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione Hydrochloride. (6c)

Starting from 4c the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (50%); mp = 167 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.91–2.08 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.15–2.36 (m, 2H, 2CH), 3.26 (app t, 6.44 Hz, 2H, 2CH), 4.80 (app t, 7.23 Hz, 2H, 2CH), 10.15 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 23.79 (CH2), 27.73 (CH2), 45.71 (CH2), 52.13 (CH), 159.25 (Cq), 178.38 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 171 (M+ free base); [α]D = −0.14 ° (RT, c = 0.58, H2O). Anal. (C6H9N3OS·HCl·1/3H2O) C, H, N, S.

5-Aminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione Hydrochloride. (6d)

Starting from 4d the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: beige crystals (71%); mp = 184 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.21 (s, 2H, CH2), 8.93 (s, 3H, NH3), 14.83 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 33.56 (CH2), 158.27 (Cq), 178.21 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 131. Anal. (C3H5N3OS·HCl) C, H, N, S.

5-Methylaminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione Hydrochloride. (6e)

Starting from 4e the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (81%); mp = 158 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.61 (s, 3H, CH3), 4.35 (s, 2H, CH2), 9.99 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 32.96 (CH3), 41.51 (CH2), 156.95 (Cq), 178.22 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 145 (M+). Anal. (C4H7N3OS·HCl) C, H, N, S.

[5-(2-Amino-ethyl)-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-thione Hydrochloride. (6g)

Starting from 4g the compound was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (94%); mp = 222 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.06–3.14 (m, 4H, CH2CH2), 8.26 (s, 3H, NH3), 14.48 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 23.85 (CH2), 35.49 (CH2), 161.02 (Cq), 178.14 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 145 (M+ free base). Anal. (C4H7N3OS·HCl) C, H, N.

General Procedures for the Synthesis of Oxadiazol-2-ones: Procedure H (Compounds 9a–c)

The tertiary amine (2 equiv) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 and cooled to 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. After adding a solution of carbonic acid bis(trichloromethyl) carbonate (1 equiv) in CH2Cl2 dropwise the mixture was refluxed. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness and the residue recrystallized or chromatographed (20–55%).

5-(1-Methyl-piperidin-4-yl)-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one. (9a)

Starting from 8a the compound was synthesized as described in procedure H, and recrystallized from methanol: white crystals (55%); mp = 281 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.84–1.98 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.05–2.15 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.69 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.84–3.03 (m, 3H, 2CH), 3.14–3.44 (m, 2H, 2CH), 10.76 (s, 1H, NH), 12.25 (s, 1H, NH); EI-MS m/z 183 (M+ free base). Anal. (C8H13N3O2·HCl·1/2H2O) C, H, N.

5-(1-Benzyl-piperidin-4-yl)-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one Hydrochloride. (9b)

Starting from 8b the compound was synthesized as described in procedure H, and recrystallized from methanol: white crystals (55%); mp = 253 °C; the NMR- and MS-data agreed with literature61. Anal. (C14H17N3O2·HCl) C, H, N.

5-Dimethylaminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-one (9c)

Starting from 8c the compound was synthesized as described in procedure H. The mixture was poured onto water and extracted with ethyl acetate at pH 7. The combined organic extracts were dried (Na2SO4), the solvent was removed under vacuo and the residue chromatographed with ethyl acetate: white crystals (20%); mp = 103 °C; Rf (ethyl acetate): 0.09; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.18 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 3.36 (s, 2H, CH2), 12.22 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 44.72 (2CH3), 53.52 (CH2), 154.76 (Cq), 155.27 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 143 (M+). Anal. (C5H9N3O2) C, H, N.

5-Cyclohexyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazole-2-one (9d)

Starting from 8d compound 9d was prepared according to procedure H, and chromatographed: colorless oil which crystallizes on standing (85%); mp = 29 °C; IR data agreed with literature62; Rf (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 2/1): 0.5; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.13–1.43 (m, 5H, 5CH), 1.58–1.70 (m, 3H, 3CH), 1.85–1.88 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.53–2.62 (m, 1H, CH), 12.03 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 24.45 (2CH2), 25.07 (CH2), 28.45 (2CH2), 34.63 (CH), 154.89 (Cq), 159.71 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 168 (M+). Anal. (C8H12N2O2·1/5H2O) C, H, N.

5-Methyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazole-2-one (9e)

Starting from 8e compound 9e was prepared according to procedure H, and recrystallized from CH2Cl2 and n-hexane: white crystals (67%); mp = 112 °C63; 13C-NMR-data agreed with literature50; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.18 (s, 3H, CH3), 11.99 (s, 1H, NH); EI-MS m/z 101 (M++1). Anal. (C3H4N2O2) C, H, N.

5-(1-Methyl-piperidin-4-yl)-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazole-2-thione (10a)

A mixture of 8a (1 equiv), pyridine (1.6 ml/equiv) and CS2 (0.2 ml/equiv) was treated at 80–90 °C until the evolution of H2S had stopped. After removing the solvent under reduced pressure the residue was recrystallized in ethanol and subsequently in methanol. The compound was chromatographed and again recrystallized from methanol: beige crystals (17%); mp = 248 °C; Rf (methanol): 0.5; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.71–1.84 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.00–2.10 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.61 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.75–2.95 (m, 3H, 3CH), 3.18–3.27 (m, 2H, 2CH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 26.99 (2CH2), 30.54 (CH), 43.72 (CH3), 53.02 (2CH2), 164.41 (Cq), 178.93 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 199 (M+). Anal. (C8H13N3OS) C, H, N, S.

5-(1-Benzyl-piperidin-4-yl)-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazole-2-thione (10b)

Was synthesized according to the synthesis described for compound 10a, starting from 8b: slightly beige crystals (34%); mp = 220 °C; Rf (chloroform/methanol = 4/1): 0.4; the NMR- and MS-data agreed with literature61. Anal. (C14H17N3OS) C, H, N, S.

5-Dimethylaminomethyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazole-2-thione (10c)

Starting from 8c the compound was synthesized as described in procedure E. The mixture was poured onto water and extracted with ethyl acetate at pH 7. The combined organic extracts were dried (Na2SO4), the solvent was removed under vacuo and the residue chromatographed: beige crystals (5%); mp = 119 °C; Rf (ethyl acetate): 0.08; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 7.45 (d, 1H, IndH), 2.31 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 3.71 (s, 2H, CH2); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 44.38 (CH3), 52.11 (CH2), 53.02 (2CH2), 160.35 (Cq), 178.80 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 159 (M+). Anal. (C5H9N3OS) C, H, N.

5-Cyclohexyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazole-2-thione (10d)

Starting from 8d compound 10d was prepared according to procedure E, and chromatographed: slightly yellow crystals (46%); mp = 81 °C; Rf (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 5/1): 0.3; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.14–1.48 (m, 5H, 5CH), 1.57–1.71 (m, 3H, 3CH), 1.90–1.93 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.74–2.84 (m, 1H, CH), 14.32 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 24.79 (2CH2), 25.34 (CH2), 29.05 (2CH2), 34.44 (CH), 167.10 (Cq), 177.87 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 184 (M+). Anal. (C8H12N2OS) C, H, N.

5-Methyl-3H-[1,3,4]oxadiazole-2-thione (10e)

Starting from 8e compound 10e was prepared according to procedure E, and chromatographed: white crystals (17%); mp = 78 °C64; Rf (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 5/1): 0.1; NMR data agreed with literature65. EI-MS m/z 117 (M++1). Anal. (C3H4N2OS) C, H, N.

General Procedures for the Synthesis of [1,3,4]Oxadiazols: Procedure I (Compounds 11, 18)

The hydrazide was refluxed for two hours in excess triethoxyalkane. Afterwards alcohol which is formed during the reaction was removed by distillation. The residue was refluxed for 5 hours. After cooling to RT, the mixture was treated with water, saturated with K2CO3 and extracted several times with ethyl acetate. The combined organic extracts were dried (Na2SO4), evaporated and chromatographed (62–66%).

1-Be nzyl-4-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-yl-piperidine. (11)

Starting from 8b and triethoxyethane the compound was prepared according to procedure I, and chromatographed starting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 1/1 and switching to methanol/ethyl acetate = 1/1: white slightly beige crystals (62%); mp = 61 °C; Rf (ethyl acetate/petroleum ether = 1/1): 0.1; Rf (methanol/ethyl acetate = 1/1): 0.4; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.64–1.77 (m, 2H, 2CH), 1.90–2.00 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.03–2.11 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.74–2.84 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.89–2.99 (m, 1H, CH), 3.45 (s, 2H, CH2-Ph), 7.18–7.32 (m, 5H, CHAr), 9.13 (s, 1H, CHOxadiazole); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 29.32 (2CH2), 32.55 (CH), 52.31 (2CH2), 62.56 (CH2), 127.17 (CH), 128.45 (2CH), 129.05 (2CH), 138.63 (Cq), 154.46 (CH), 168.67; EI-MS m/z 244 (M+). Anal. (C14H17N3O) C, H, N.

4-Benzyl-5-piperidin-4-yl-2,4-dihydro-[1,2,4]triazol-3-one Hydrochloride. (16a)

Starting from 14a compound 16a was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (66%); mp = 251 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.65–1.80 (m, 4H, 4CH), 2.77–2.95 (m, 3H, 3CH), 3.15–3.25 (m, 2H, 2CH), 4.81 (s, 2H, CH2-Ph), 7.21–7.37 (m, 5H, CHAr), 8.85–9.25 (m, 2H, NH2), 11.70 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 26.29 (2CH2), 30.21 (CH), 42.48 (2CH2), 43.36 (CH2), 78.44 (Cq), 127.19 (2CH), 127.89 (CH), 129.03 (2CH), 137.31 (Cq), 149.47 (Cq), 155.30 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 258 (M+). Anal. (C13H19N4O·HCl·5/4H2O) C, H, N.

5-Aminomethyl-4-benzyl-2,4-dihydro-[1,2,4]triazol-3-one. (16d)

Starting from 12d compound 16a was synthesized as described in procedure L, since no precipitate was formed the mixture was extracted with several portions of ethyl acetate. The combined organic extracts were dried (Na2SO4) and the solvent evaporated under vacuo until the crystallization started: white crystals (44%); mp = 150 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.78 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.44 (s, 2H, CH2N), 4.86 (s, 2H, CH2-Ph), 7.22–7.37 (m, 5H, CHAr), 11.55 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 37.76 (CH2), 43.30 (CH2), 127.35 (2CH), 127.80 (CH), 128.96 (2CH), 137.38 (Cq), 148.79 (Cq), 155.73 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 204 (M+). Anal. (C10H12N4O) C, H, N.

4-Benzyl-5-piperidin-4-yl-2,4-dihydro-[1,2,4]triazol-3-thione Hydrochloride. (17a)

Starting from 15 compound 17a was synthesized as described in procedure F: white crystals (95%); mp = 285 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.63–1.78 (m, 4H, 4CH), 2.79–2.91 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.98–3.08 (m, 1H, CH), 3.14–3.22 (m, 2H, 2CH), 5.27 (s, 2H, Ch2-Ph), 7.26–7.37 (m, 5H, CHAr), 8.68–9.04 (m, 2H, NH2), 13.83 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 26.64 (2CH2), 30.31 (CH), 42.49 (2CH2), 45.91 (CH2), 127.36 (2CH), 128.12 (CH), 129.03 (2CH), 136.29 (Cq), 154.60 (Cq), 167.43 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 274 (M+). Anal. (C14H18N4S·HCl·5/4H2O) C, H, N, S.

5-Aminomethyl-4-benzyl-2,4-dihydro-[1,2,4]triazol-3-thione. (17d)

Starting from 13d compound 17d was synthesized as described in procedure L, and chromatographed with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 1/3 to wash off most of the intermediate BOC-protected triazole-3-thione, and then with ethyl acetate/methanol = 1/5, and subsequently with CHCl3/methanol = 4/1: white crystals (11%); mp = 69 °C; Rf (CHCl3/methanol = 4/1): 0.52; white crystals (11%); mp = 158 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.07 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.15 (s, 1H, NH), 3.55 (s, 2H, CH2NH2), 5.32 (s, 2H, CH2-Ph), 7.26–7.39 (m, 5H, CHAr); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 37.23 (CH2), 45.71 (CH2), 127.39 (2CH), 128.02 (CH), 128.98 (2CH), 136.24 (Cq), 153.74 (Cq), 167.89 (Cq); EI-MS m/z 220 (M+). Anal. (C10H12N4S·9/10H2O) C, H, N, S.

4-(5-Methyl-[1,3,4]oxadiazol-2-yl)-piperidine Hydrochloride. (19)

Starting from 18 the compound was synthesized as described in general procedure G (56%); the corresponding hydrobromide was obtained by stirring 2.6 mmol of 18 in 1 mL of HBr in Acetic Acid (5.7 M) under a nitrogen atmosphere overnight (98%). Analytical data for the hydrochloride: mp = 193 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.85–1.99 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.09–2.14 (m, 2H, 2CH), 2.45 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.94–3.05 (m, 2H, 2CH), 3.22–3.33 (m, 3H, 3CH), 9.11–9.35 (m, 2H, NH2); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 10.80 (CH3), 25.66 (2CH2), 30.24 (CH), 42.13 (2CH2), 163.98 (Cq), 167.68 (Cq). Anal. (C8H13N3O·HCl·5/3H2O) C, H, N.

[3H]Muscimol Ligand binding assays