New approaches are needed to fight the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, now in its third decade in the United States. The epidemiology of HIV in the past decades illustrates these new challenges. Annual incident cases of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) declined 38% and deaths from AIDs declined 63% between 1995 and 1998, due primarily to the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART).1,2 However, the annual number of incident AIDS cases and deaths remained stable from 1999 through 2006, and the estimated number of new HIV infections occurring annually in the U.S. has remained stable since 2000.1,3

This article seeks to put the current emphasis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on HIV testing programs in the context of the epidemiology of the U.S. HIV epidemic; to describe major CDC prevention initiatives that involve HIV testing, focusing on the Advancing HIV Prevention (AHP) initiative;4 and to describe what has been learned in the first five years since new strategies for preventing HIV infection were outlined in the AHP initiative.

BACKGROUND

Part of the explanation of why HIV and AIDS incidence rates have not declined in the last decade relates to patterns of HIV testing and knowledge of HIV serostatus. HIV testing is the gateway to medical treatment of HIV disease and for taking steps to protect one's sex and drug-using partners from exposure to HIV infection. Yet, undiagnosed HIV infection remains a considerable challenge. Of the estimated one million people in the U.S. living with HIV infection in 2003, approximately one-quarter were not aware they were infected,5 and a greater proportion of people at high risk for infection were unaware of their serostatus, including people from racial/ethnic minority groups, men who have sex with men (MSM), and particularly MSM of color.6,7 When people are diagnosed with HIV infection early in the course of their disease and seek treatment, the onset of AIDS can be delayed considerably. Early diagnosis of HIV infection is important because it maximizes the benefits of HIV care, offers the opportunity for monitoring and timely initiation of ART, and may reduce morbidity and mortality from and transmission of HIV infection.2,8,9 Knowledge of serostatus also leads to reduction of the risk of transmission of HIV to sex partners. A substantial proportion of HIV-infected people reduce sexual behaviors likely to transmit HIV after becoming aware of their HIV infection.10–13 Thus, HIV testing represents secondary prevention for people who learn their HIV status and primary prevention for the community.

Although HIV counseling and testing have been mainstays of HIV prevention programs since the licensure of the first enzyme immunoassay to detect HIV antibodies in 1985, testing technologies have improved, offering new possibilities to utilize HIV testing as a prevention approach. Simple, rapid HIV tests that use finger-stick whole-blood or oral fluid specimens and yield results within 10 to 20 minutes have made HIV testing more available in a variety of clinical and nonclinical settings, and have increased the proportion of people who receive their test results. These rapid tests continue to be important tools for diagnosing HIV earlier in the course of illness.14

In response to the persistent problem of individuals lacking awareness of their HIV serostatus, and with the promise of new HIV technologies, CDC has taken a series of steps to use HIV testing as an HIV prevention approach. In 2001, CDC first described the Serostatus Approach to Fighting the HIV Epidemic, called SAFE, which comprised action steps for diagnosing HIV infection in all infected people and linking them to care.15 In 2003, CDC issued explicit recommendations to incorporate HIV prevention as part of medical care of HIV-infected patients16 and announced new strategies for the changing epidemic—the AHP initiative—which was largely focused on revitalizing HIV testing approaches in the U.S.4 The four priority AHP strategies were to (1) make HIV testing a routine part of medical care, (2) implement new models for diagnosing HIV infections outside medical settings, (3) prevent new infections by working with people diagnosed with HIV and their partners, and (4) further decrease perinatal HIV transmission.4

LAYING THE FOUNDATION FOR IMPLEMENTING AHP ACTIVITIES TO PROMOTE HIV TESTING

The AHP initiative built upon experience of the past two decades and proposed new strategies modeled on proven approaches.17 To determine the best ways to implement AHP strategies, CDC staff consulted with community advocates, members of affected communities, state and local health departments, policy makers, national organizations, politicians, and federal advisory bodies.18

The plan to roll out AHP activities had several important components. First, CDC provided funds for demonstration projects—opportunities for HIV prevention organizations, including community-based organizations (CBOs) and health departments—to demonstrate how HIV rapid testing technologies could be used in diverse settings to increase access to testing and operationalize rapid HIV testing in these settings. Second, CDC prepared an interim technical guidance to assist HIV prevention providers with implementation or refinement of HIV testing programs while the demonstration projects were being conducted. Finally, CDC has supported the incorporation of components of AHP into prevention programs by providing resources (HIV test kits and cooperative agreement funds) and training to state and local health departments.

AHP demonstration projects

In 2003, CDC awarded $23 million to nine health departments and 16 CBOs to conduct seven projects demonstrating the effectiveness of different models for implementing the key AHP strategies. In 2004, five health departments, 14 CBOs, four medical facilities, and three historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were awarded $4 million to conduct two additional demonstration projects. Six of the nine AHP demonstration projects included the provision of HIV testing in a variety of clinical and nonclinical settings to identify people with unrecognized HIV infection.

Interim technical guidance

CDC drafted the interim technical guidance for HIV prevention grantees in 2003 to facilitate adoption of routine HIV testing in medical and correctional settings, rapid HIV testing in nonclinical settings, partner counseling and referral services (PCRS) for the partners of people reported with HIV infection, risk reduction for people living with HIV, prevention in medical care settings, and universal HIV testing of pregnant women.17 The interim technical guidance outlined principles for working with partners and for monitoring and evaluating activities, and it detailed information about expanding HIV testing in clinical, nonclinical, and correctional facilities, as well as prevention interventions for people living with HIV. CDC also provided training and technical assistance to grantees to help them implement AHP activities.

Provision of resources to state and local health departments

CDC spent $6.4 million to purchase test kits from 2003 through 2006 to stimulate the adoption of rapid HIV testing and to assess the feasibility of using rapid test kits in diverse settings. Data about distribution of HIV test kits are available for 2003 through 2005. During this time, more than 500,000 rapid HIV test kits were distributed to 230 organizations, including 197 health departments and CBOs in 36 states.19

DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS

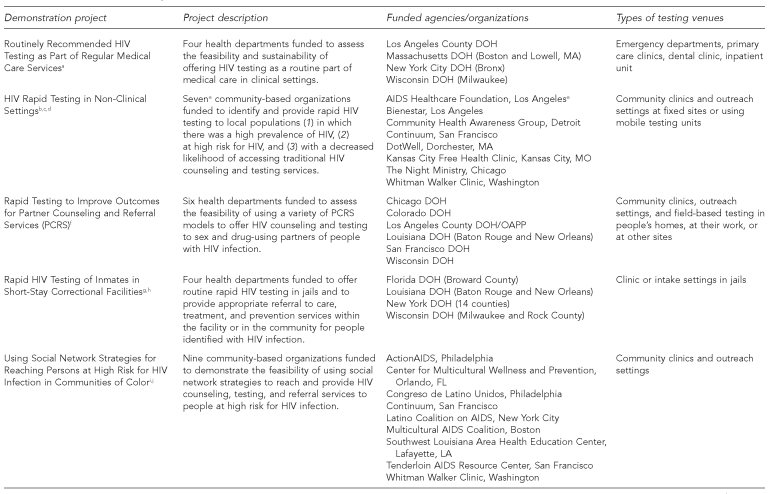

The six demonstration projects that included HIV testing were as follows:

Routinely Recommended HIV Testing as Part of Regular Medical Care Services (medical settings project)20

HIV Rapid Testing in Non-Clinical Settings21

Rapid Testing to Improve Outcomes for Partner Counseling and Referral Services22

Routine Rapid HIV Testing of Inmates in Short-Stay Correctional Facilities23

Using Social Network Strategies for Reaching Persons at High Risk for HIV Infection in Communities of Color24

Implementation of Rapid HIV Testing in HBCUs and Alternative Venues and Populations: Linkage to HIV Care25

The three demonstration projects that did not offer HIV testing but sought instead to prevent new HIV infections by working with HIV-infected people include:

Incorporating HIV Prevention into Medical Care Settings26

Prevention Case Management for Persons Living with HIV/AIDS27

Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study (ARTAS) II: Linkage to HIV Care28

A description of the demonstration projects that included HIV testing is provided in the Figure. These projects offered HIV testing in clinical, nonclinical, and/or correctional settings. The PCRS project offered rapid HIV testing in conjunction with HIV partner services, and the social networks project used HIV-infected people and others who were not infected with HIV but who were considered to be at high risk for HIV infection to recruit participants for testing from their social, sexual, and drug-using networks. Rapid HIV testing was conducted by staff trained to provide HIV counseling and testing or by existing clinical staff who were trained to provide HIV testing at participating sites. Surveys collected information from people who were tested about demographic and behavioral characteristics and HIV testing history at all participating sites, although only a sample of people with negative rapid HIV test results were surveyed in three of the settings (ambulatory care, HBCUs, and migrant/farm worker) in the HBCU/alternative venues project.

Figure. Summary of funded Advancing HIV Prevention demonstration projects in which rapid HIV testing was conducted—United States, 2003–2007.

aRapid HIV testing in emergency departments—three U.S. sites, January 2005–March 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(24):597-601.

bBowles KE, Clark HA, Tai E, Sullivan PS, Song B, Tsang J, et al. Implementing rapid HIV testing in outreach and community settings: results from an Advancing HIV Prevention demonstration project conducted in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):78-85.

cRapid HIV testing in outreach and other community settings—United States, 2004–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(47):1233-7.

dClark HA, Bowles KE, Song B, Heffelfinger JD. Implementation of rapid HIV testing programs in community and outreach settings: perspectives from staff at eight community-based organizations in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):86-93.

eAIDS Healthcare Foundation was not funded directly by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a demonstration project site but rather was subcontracted by Bienestar to offer rapid HIV testing.

fBegley EB, Oster AM, Song B, Lesondak L, Voorhees K, Esquivel M, et al. Incorporating rapid HIV testing into partner counseling and referral services. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):126-35.

gMacGowan R, Margolis A, Richardson-Moore A, Wang T, Lalota M, French PT, et al. Voluntary rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in jails. Sex Transm Dis 2007 Aug 23 [E-pub ahead of print].

hMacGowan R, Goldsmith G, Margolis A. Rapid HIV testing in a “rapid” environment—jails. Correctional Health Care Rep 2007;8:33,34,41-6.

iUnpublished data, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008.

jUse of social networks to identify persons with undiagnosed HIV infection—seven U.S. cities, October 2003–September 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54(24):601-5.

kThomas PE, Heffelfinger J. Assessing students' barriers to being tested for HIV on historically black college and university campuses. Presented at the American Public Health Association 135th Annual Meeting and Expo; 2007 Nov 3–7; Washington.

lThomas PE, Voetsch AC, Song B, Calloway D, Goode C, Mundey L, et al. HIV risk behaviors and testing history in historically black college and university settings. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):115-25.

mSchulden JD, Song B, Barros A, Mares-DelGrasso A, Martin CW, Ramirez R, et al. Rapid HIV testing in transgender communities by community-based organizations in three cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):101-14.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

DOH = department of health

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

PCRS = partner counseling and referral services

OAPP = Office of Aids Programs and Policy

HBCU = historically black college/university

FINDINGS AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS THAT INCLUDED HIV TESTING

We summarized the lessons learned from demonstration projects that included HIV testing based on several sources: data on HIV testing services provided and proportion of those tested with newly identified HIV infection; qualitative information on barriers to and facilitators of HIV testing provided by project sites in progress reports and project summaries; and qualitative information gathered from principal investigators and project staff as part of closeout meetings and more formal project evaluations.

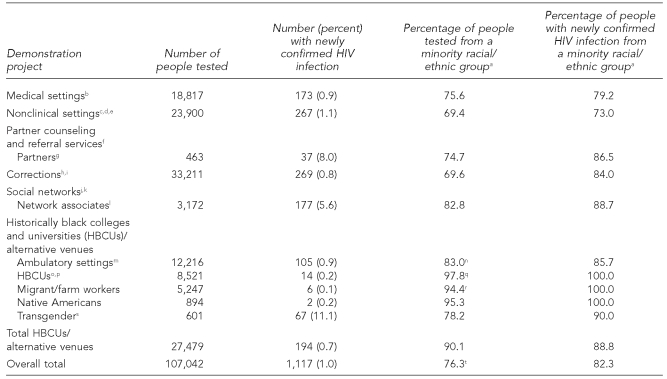

Data on HIV testing services

More than 107,000 rapid HIV tests were performed in six demonstration projects from 2003 through 2007, and more than 1,100 people (1% of those tested) were newly diagnosed with HIV infection (Table). The proportion of positive tests that represented new HIV diagnoses, by project, ranged from less than 1% to 8%. Overall, approximately three-quarters of people tested and more than 80% of people with newly confirmed HIV infection were African Americans, Hispanics, or Native Americans/Alaska Natives. Four of the projects each tested more than 18,000 people (Table). The highest proportions of confirmed new HIV diagnoses were in transgender (TG) sites (11% among all TG participants; 12% among male-to-female TG participants), PCRS sites (8%), and social networks sites (6%).

Table. Summary of rapid HIV tests performed, new diagnoses of HIV infection identified, and proportion of tests performed and new diagnoses made among racial/ethnic minority groups—six Advancing HIV Prevention demonstration projects, 2003–2007.

aNative American/Alaska Native (NA/AN) for NA/AN sites participating in the HBCU/alternative venues project. African American race and/or Hispanic ethnicity for all other project sites.

bRapid HIV testing in emergency departments—three U.S. sites, January 2005–March 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(24):597-601.

cBowles KE, Clark HA, Tai E, Sullivan PS, Song B, Tsang J, et al. Implementing rapid HIV testing in outreach and community settings: results from an Advancing HIV Prevention demonstration project conducted in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):78-85.

dRapid HIV testing in outreach and other community settings—United States, 2004–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(47):1233-7.

eClark HA, Bowles KE, Song B, Heffelfinger JD. Implementation of rapid HIV testing programs in community and outreach settings: perspectives from staff at eight community-based organizations in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):86-93.

fBegley EB, Oster AM, Song B, Lesondak L, Voorhees K, Esquivel M, et al. Incorporating rapid HIV testing into partner counseling and referral services. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):126-35.

gData for partners who were interviewed and tested

hMacGowan R, Margolis A, Richardson-Moore A, Wang T, Lalota M, French PT, et al. Voluntary rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in jails. Sex Transm Dis 2007 Aug 23 [E-pub ahead of print].

iMacGowan R, Goldsmith G, Margolis A. Rapid HIV testing in a “rapid” environment—jails. Correctional Health Care Rep 2007;8:33,34,41-6.

jUnpublished data, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008

kUse of social networks to identify persons with undiagnosed HIV infection—seven U.S. cities, October 2003–September 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54(24):601-5.

lNetwork associates were social, sexual, or drug-using contacts of people infected with or at high risk for infection with HIV. These network associates were interviewed and tested for HIV infection.

mRapid HIV testing in emergency departments—three U.S. sites, January 2005–March 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(24):597-601.

nThis is an estimate because information on race/ethnicity was only collected from 11,116 patients who received HIV testing at ambulatory care sites (this data was available for all people with newly confirmed HIV infection and most people who had negative rapid HIV test results).

oThomas PE, Heffelfinger J. Assessing students' barriers to being tested for HIV on historically black college and university campuses. Presented at the American Public Health Association 135th Annual Meeting and Expo; 2007 Nov 3–7; Washington.

pThomas PE, Voetsch AC, Song B, Calloway D, Goode C, Mundey L, et al. HIV risk behaviors and testing history in historically black college and university settings. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):115-25.

qThis is an estimate because information on race/ethnicity was only collected from 5,232 people who received HIV testing at HBCUs (this data was available for all people with newly confirmed HIV infection and a sample of people who had negative rapid HIV test results).

rThis is an estimate because information on race/ethnicity was only collected from 3,138 people who received HIV testing at migrant/farm worker sites (this data was available for all people with newly confirmed HIV infection and a sample of people who had negative rapid HIV test results).

sSchulden JD, Song B, Barros A, Mares-DelGrasso A, Martin CW, Ramirez R, et al. Rapid HIV testing in transgender communities by community-based organizations in three cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123(Suppl 3):101-14.

tThis is an estimate because information on race/ethnicity was not collected from some people who received HIV testing at several sites in the HBCU/alternative venues project. In the HBCU/alternative venues project, these data were collected from a sample of people tested at ambulatory sites, HBCUs, and migrant/farm worker sites (see footnotes n, q, and r).

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

HBCU = historically black college/university

Four projects collected information about acceptance of HIV testing. In HIV testing programs conducted during a one-year period at three participating emergency departments (EDs), 56% (range by site: 53% to 98%) of eligible patients accepted testing.29 In the two sites in the nonclinical settings project that collected information about acceptance of testing, 60% of people who were offered testing agreed to be tested.30 The most common reasons that people in the nonclinical settings project gave for declining testing were that they had been tested for HIV recently (37%), they did not have time to be tested (17%), and they were not prepared to receive test results on the same day as testing (12%).30 Of the risk partners who were offered HIV testing in the PCRS project, 78% of those who had not been previously diagnosed with HIV infection accepted testing.31 HBCU students identified several important barriers to testing: fear of the reaction from others, fear of testing positive, concerns about confidentiality at student health centers, and lack of awareness about the availability of HIV testing on campuses.32

Most of the projects reached people with well-known risk behaviors. From 2% (corrections project) to 30% (PCRS project) of the participants who were tested reported male-male sex, and from 6% (nonclinical settings project) to 18% (social networks project [Unpublished data, CDC, 2008]) reported injection drug use.31,33,34 Thirty percent of people tested in the nonclinical settings project, 34% of inmates tested in the corrections project, and 42% of people surveyed and tested at HBCUs in the HBCU/alternative venues project had never before been tested for HIV.33–35 Among TG people who were tested in the HBCU/alternative settings project,36 93% self-identified as male-to-female (MTF) TG and 7% as female-to-male (FTM) TG. Only 8% of MTF TG participants had never been tested for HIV, but 37% reported unprotected receptive anal intercourse in the preceding 12 months. Of the FTM TG participants, 14% had never been tested for HIV and 29% reported having unprotected receptive anal intercourse in the past year.36

Barriers to and facilitators of HIV testing

Chief among programmatic barriers to expanding HIV testing in both clinical and nonclinical settings were limited resources, logistical difficulties of testing large numbers of people (particularly in clinical and correctional settings), local and state regulations restricting HIV testing, and difficulties ensuring linkage to care (particularly in nonclinical settings).37 Participants in the medical settings project also identified lack of buy-in by staff and competing priorities for limited resources. Challenges identified by a substantial proportion of staff in nonclinical settings included delivering preliminary positive test results in outreach settings (39%) and delivering negative confirmatory test results to people who had reactive rapid test results (35%).38

Unique barriers identified in the PCRS project included the high percentage of anonymous partners reported by HIV-infected people, difficulties locating partners for referral to testing and prevention services, concerns about maintaining the confidentiality of HIV-infected people who were being asked to name their partners, conducting quality assurance for rapid HIV testing in the field, and reluctance by staff at collaborating CBOs to assist with partner elicitation activities. Challenges in the corrections project included determining who should provide testing in jails (i.e., staff from jails, health departments, or CBOs), gaining admission into facilities for staff at collaborating CBOs, and ensuring the security and safety of CBO staff.39

Several key lessons were derived from the projects. In EDs, the approach used to conduct HIV testing may influence how many people can be tested and the prevention messages that can be provided. EDs that used a counselor-based approach to HIV testing were able to provide in-depth risk assessment and prevention counseling, but test only a small fraction of their patients.29 In contrast, the ED that used existing staff and streamlined procedures for obtaining consent and providing pre- and posttest information was able to test many more patients but provide only limited risk assessment and prevention counseling to people who had negative rapid test results.29 Staff implementing HIV testing in outreach and community settings learned that it was very important to work closely with other service organizations and with health departments to understand the local HIV epidemic and identify appropriate venues for targeting people at greatest risk for infection and those less likely to use health-care or testing services.30

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT AND STRATEGIC CHANGES

The findings of the AHP demonstration projects that included testing have been disseminated in multiple ways, used in the formulation of HIV prevention policies and intervention packages by CDC and local partners, and used as formative experiences in addressing HIV prevention needs in the highest risk populations in the U.S.

Dissemination of findings

Findings from four projects have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,29,32,40 and articles describing findings from all six projects have already been published34,39 or are included in this special issue of Public Health Reports.30,31,35,36,38,41

Use of findings to guide policy decisions and recommendations

Knowledge gained during these projects informed activities of CDC's Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention to (1) increase the proportion of HIV-infected people who know their HIV serostatus by improving access to HIV testing services in community and health-care settings, (2) reduce disparities in access to and use of testing services, and (3) increase linkage to care for people who are identified with HIV infection. Findings from these projects were used to help develop CDC's revised recommendations for HIV testing in health-care settings in 2006,42 and the HIV counseling and testing section of CDC's provisional procedural guidance for CBOs.43 In addition, the findings are informing the revision of the guidelines for providing partner services and are being used to implement HIV testing in correctional settings.

The 2006 recommendations for HIV testing in health-care settings call for voluntary, opt-out HIV screening of all patients aged 13 to 64 years in U.S. health-care settings.42 CDC has also used the expertise gained from these projects to develop implementation guidance to assist providers and facilities that are considering adoption of opt-out HIV screening. Because the social networks strategy was found to be so successful in reaching people with undiagnosed HIV infection, CDC issued a “Dear Colleague” letter in 2005 that formally endorsed this strategy for grantees44 and developed a training curriculum to support its adoption.

Use of findings to address pressing HIV prevention needs

The AHP demonstration projects that included HIV testing were successful in reaching racial/ethnic minorities and many people with self-reported risk factors for HIV infection. Despite important progress in HIV prevention activities, racial disparities in the prevalence and incidence of HIV/AIDS and major unmet needs persist in African American communities.45 Almost half of CDC's domestic HIV prevention budget is directed to fighting HIV in African American communities. CDC launched the Heightened National Response (HNR) to the HIV/AIDS Crisis among African Americans in March 2007. The key focus areas of HNR are to (1) expand HIV testing activities, (2) ensure that more health-care providers receive training to foster routine HIV screening among African American patients, (3) employ new efforts to motivate African American men and women to seek testing, (4) reduce the stigma associated with testing, and (5) identify new venues for rapid HIV testing in African American communities.45

In 2007, CDC awarded $35 million to 23 health departments to support HIV testing, screening, and related activities, including the purchase of rapid HIV test kits, to increase HIV testing opportunities for populations disproportionately affected by HIV, particularly African Americans who are unaware of their HIV status. CDC's goals for this program are to test 1.5 million people for HIV and identify 20,000 individuals who are infected with HIV but unaware of their HIV status.46

CONCLUSION

More people than ever before in the course of the HIV/AIDS epidemic are living with HIV in the U.S. Advances in treatment have made it possible for people infected with HIV to live longer, healthier lives. CDC regards people living with HIV infection as essential partners in HIV prevention. Optimally, engaging individuals with HIV infection as prevention partners requires helping them to learn their HIV-infection status. The AHP strategies were designed to give people easier access to testing to learn their HIV status, receive appropriate treatment and prevention services, and help protect other people from becoming infected. These demonstration projects serve as the foundation for stronger, more effective programs based on proven public health principles that will serve to target proven interventions more effectively, reduce transmission, and realize new successes in the fight against HIV.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV/AIDS surveillance report, volume 18: cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2006. Atlanta: CDC; 2008. [cited 2008 Jul 2]. pp. 1–55. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2006report/pdf/2006SurveillanceReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palella FJ, Jr., Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, Moorman AC, Wood KC, Greenberg AE, et al. Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:620–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 2];U.S. HIV and AIDS cases reported through December 2001. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2001. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2001report/pdf/2001surveillance-report_year-end.pdf.

- 4.Advancing HIV prevention: new strategies for a changing epidemic—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(15):329–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glynn M, Rhodes P. Estimated HIV prevalence in the United States at the end of 2003 [abstract T1-B1101]; Programs and abstracts of the 2005 National HIV Prevention Conference; 2005 Jun 12–15; Atlanta. [cited 2008 Jul 2]. Also available from: URL: http://www.aegis.com/conferences/nhivpc/2005/t1-b1101.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unrecognized HIV infection, risk behaviors, and perceptions of risk among young black men who have sex with men—six U.S. cities, 1994–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(33):733–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Secura GM, Behel S, Bingham T, Celentano DD, et al. Unrecognized HIV infection, risk behaviors, and perceptions of risk among young men who have sex with men: opportunities for advancing HIV prevention in the third decade of HIV/AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:603–14. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141481.48348.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Rakai Project Study Group. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill A. Progression to AIDS and death in the era of HAART. AIDS. 2006;20:1067–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000222082.36787.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolitski RJ, MacGowan RJ, Higgins DL, Jorgensen CM. The effects of HIV counseling and testing on risk-related practices and help-seeking behavior. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9(3) Suppl:52–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denning PH, Nakashima AK, Wortley P. High-risk sexual behaviors among HIV-infected adolescents and young adults (abstract no. 113); the National HIV Prevention Conference; 1999 Aug 2–Sep 1; Atlanta. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickman NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adoption of protective behaviors among persons with recent HIV infection and diagnosis—Alabama, New Jersey, and Tennessee, 1997–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(23):512–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchinson AB, Branson BM, Kim A, Farnham PG. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of alternative HIV counseling and testing methods to increase knowledge of HIV status. AIDS. 2006;20:1597–604. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238405.93249.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen RS, Holtgrave DR, Valdiserri RO, Shepherd M, Gayle HD, DeCock KM. The Serostatus Approach to Fighting the HIV Epidemic: prevention strategies for infected individuals. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1019–24. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC (US), Health Resources and Services Administration (US), National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Recommendations of CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-12):1–24. [published erratum appears in MMWR Recomm Rep 2004;53(32):744] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Advancing HIV prevention: interim technical guidance for selected interventions. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/guidelines/pdf/AHPIntGuidfinal.pdf.

- 18.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Advancing HIV prevention: progress summary, April 2003–September 2005. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/progress_2005.htm.

- 19.Rapid HIV test distribution—United States, 2003–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(24):673–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for state and local health departments: routinely recommended HIV testing as part of regular medical care services. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/Test_Regular_Med_Care_Svcs.htm.

- 21.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for community-based organizations (CBOS): HIV rapid testing in non-clinical settings. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/AHPDemoRapidTestNonclin.htm.

- 22.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for state and local health departments: HIV rapid testing to improve outcomes for partner counseling, testing, and referral services (PCTRS) Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/PCTRS.htm.

- 23.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for state and local health departments: routine rapid HIV testing of inmates in short-stay correctional facilities. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/Correctional_Facilities.htm.

- 24.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for community-based organizations (CBOs): using social network strategies for reaching persons at high risk for HIV infection in communities of color. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/SNDP.htm.

- 25.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for implementation of rapid HIV testing in historically black colleges and universities and alternative venues and populations. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/DemoProject_Rapid_black.htm.

- 26.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for primary care providers: incorporating HIV prevention into medical care settings (PICS) Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/PICS.htm.

- 27.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for community-based organizations (CBOs): prevention case management (PCM) for persons living with HIV/AIDS. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/PCM.htm.

- 28.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Demonstration projects for health departments and community-based organizations (CBOs): antiretroviral treatment access study (ARTAS) II: linkage to HIV care. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/factsheets/ARTASSII.htm.

- 29.Rapid HIV testing in emergency departments—three U. S. sites, January 2005–March 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(24):597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowles KE, Clark HA, Tai E, Sullivan PS, Song B, Tsang J, et al. mplementing rapid HIV testing in outreach and community settings: results from an Advancing HIV Prevention demonstration project conducted in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):78–85. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Begley EB, Oster AM, Song B, Lesondak L, Voorhees K, Esquivel M, et al. Incorporating rapid HIV testing into partner counseling and referral services. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):126–35. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas PE, Heffelfinger J. Assessing students' barriers to being tested for HIV on historically black college and university campuses. the American Public Health Association 135th Annual Meeting and Expo; 2007 Nov 3–7; Washington. Presented at. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapid HIV testing in outreach and other community settings—United States, 2004–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(47):1233–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacGowan R, Margolis A, Richardson-Moore A, Wang T, Lalota M, French PT, et al. Voluntary rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in jails. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Aug 23; doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318148b6b1. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas PE, Voetsch AC, Song B, Calloway D, Goode C, Mundey L, et al. HIV risk behaviors and testing history in historically black college and university settings. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):115–25. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulden JD, Song B, Barros A, Mares-DelGrasso A, Martin CW, Ramirez R, et al. Rapid HIV testing in transgender communities by community-based organizations in three cities. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):101–14. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heffelfinger JD, Begley E, Boyett B, Gardner LI, Kimbrough L, Margolis AD, et al. Reducing barriers to early diagnosis and care for HIV infection: lessons learned from the Advancing HIV Prevention (AHP) demonstration projects, 2003–2007 [abstract C06-1]. Programs and abstracts of the 2007 National HIV Prevention Conference; 2007 Dec 2–5; Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark HA, Bowles KE, Song B, Heffelfinger JD. Implementation of rapid HIV testing programs in community and outreach settings: perspectives from staff at eight community-based organizations in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):86–93. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacGowan R, Goldsmith G, Margolis A. Rapid HIV testing in a “rapid” environment—jails. Correctional Health Care Rep. 2007;8:33. 34, 41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Use of social networks to identify persons with undiagnosed HIV infection—seven U. S. cities, October 2003–September 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(24):601–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shrestha RK, Clark HA, Sansom SL, Song B, Buckendahl B, Calhoun CB, et al. Cost-effectiveness of finding new HIV diagnoses using rapid HIV testing in community-based organizations. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):94–100. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Provisional procedural guidance for community-based organizations. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/AHP/resources/guidelines/pdf/pro_guidance.pdf.

- 44.Letter from CDC to Health Departments, Key Partners, and Grantees. 2005 Sep 13. Letter on file with authors

- 45.CDC (US) Fighting HIV among African Americans: a heightened national response. [cited 2008 Jul 3];CDC Media Facts, March 2007. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/resources/factsheets/pdf/AA_response_media_fact.pdf.

- 46.CDC (US) [cited 2008 Jul 3];Funding announcement for CDC program “Expanded and Integrated Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Testing for Populations Disproportionately Affected by HIV, Primarily African Americans”. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/od/pgo/funding/PS07-768.htm.