SYNOPSIS

Objectives.

We report on the rates of patient acceptance and their perceptions of routine emergency department (ED) human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in a high-prevalence area.

Methods.

We analyzed the race/ethnicity of patients who either accepted or declined a routine HIV test that was offered to all patients in the ED of a large academic center. We also distributed a patient perception survey about ED HIV testing.

Results.

During the study period, an HIV screening test was offered to 9,826 patients. Of these, 5,232 patients (53%) accepted the test. The acceptance rate of HIV testing was highest among African American patients (55%), followed by 52% for white, 50% for Hispanic, and 42% for Asian patients. A total of 1,519 completed surveys were returned for analysis. The most common reasons for declining a test were that patients did not perceive themselves to be at risk for HIV (49%) or they had recently been tested for HIV (18%). Overall, 84% of patients stated they would recommend to a friend to get an HIV test in the ED. When analyzed by ethnicity, 89% of African American patients stated they would recommend to a friend to get an HIV test if the friend went to the ED, but only 74% of white patients would do so.

Conclusions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 2006 recommendations on HIV screening are well accepted by the target populations. Further work at explaining the risk of HIV infection to ED patients should be undertaken and may boost the acceptance rate of ED HIV screening.

In September 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published revised recommendations for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening in a number of health-care settings.1 Among these were recommendations that where the prevalence of HIV infection is greater than 0.1%, emergency department (ED) patients aged 13 to 64 years be offered an HIV test, regardless of their perceived risk. Since then, there has been a great deal of interest in and increasing federal support of the implementation of these recommendations as they affect EDs. For example, CDC has sponsored a number of workshops across the U.S. that bring together those with expertise in ED HIV screening with those who wish to implement the process in their own ED.

Federal money is also being targeted to support expanded ED HIV testing. In September 2007, CDC awarded $35 million to support increased HIV testing, and much of this money will be used to finance EDs offering testing to high-risk populations. While slowly being introduced to EDs across the U.S., these recommendations have been criticized for not addressing patient concerns about the testing process.2 However, to date there has been little research on patients' perceptions, particularly by race/ethnicity. In this study, we analyzed by patient race/ethnicity the acceptance rates of the ED HIV test, perceptions of ED HIV testing, and reasons for not testing, to better understand factors that may be associated with ED test acceptance.

METHODS

ED HIV testing

The study was performed at an academic medical center ED in a setting with high HIV prevalence, where routine opt-out HIV screening is offered to patients regardless of risk characteristics. The methodology of this program has been described in detail elsewhere.3

In brief, an ED triage nurse informed patients aged 13 to 64 years (both ambulatory and those arriving by ambulance) of the availability of a free HIV screening test, and also gave them written information about HIV infection and the importance of HIV testing. At a subsequent mutually convenient point during the ED evaluation, which varied from patient to patient, an HIV screener approached the patient and reiterated that an HIV screening test was being offered to all ED patients, regardless of their perceived risk of infection, and that they could opt out of the screening test if they wished. Patients who accepted screening were tested with an oral fluid swab using the OraQuick Advance® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania). Testing was performed in parallel to the provision of standard ED care. Results were available within 20 to 40 minutes, and negative results were relayed to the patient by the screener. Individuals who tested preliminary positive were seen by the attending emergency physician and referred to an infectious disease physician while in the ED for follow-up and linkage to confirmatory testing and care. The screening program was offered daily from 8 a.m. to 12 a.m. Screening personnel collected data on age, gender, race, insurance status, zip code of residence, acceptance or refusal of HIV testing, and test results for each patient.

Patient perception survey

Trained researchers distributed a 15-question structured survey to a convenience sample of patients during a nine-month study period. The surveys were distributed daily between 8 a.m. and 12 a.m., and were anonymous. The survey was offered to patients who had both accepted or declined a previously offered rapid HIV test, as well as those who may not have been offered the test at all. The survey included questions on whether they were offered the test, whether they accepted the test, and their perceptions of testing in the ED, including such questions as, “Would you recommend to a friend to get an HIV test in the ER?” (yes/no response) and, “In your opinion, do you agree that the ER is a good place to perform HIV screening?” The latter was assessed using a Likert scale consisting of strongly disagree, disagree, no opinion, agree, and strongly agree as possible responses. Individuals who declined the test were asked about the reasons for refusal. The survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the medical center.

Frequencies for testing acceptance and responses to perception questions were evaluated by race/ethnicity using Chi-square and Fisher's Exact tests. Data were analyzed using STATA 9.0se.4

RESULTS

Acceptance of ED HIV testing

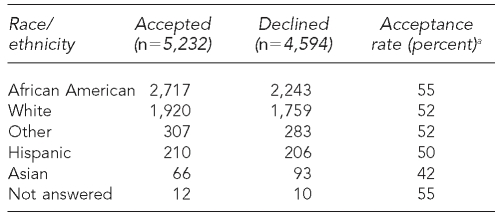

The ED HIV testing program was in operation for 15 months at the time of the data analysis. During this period, an HIV screening test was offered to 9,826 patients. Of these, 5,232 patients (53%) accepted the test. The acceptance rate of HIV testing itself was highest among African Americans, 55% of whom accepted the test when offered. Among other racial/ethnic groups, the acceptance rate was 52% for white, 50% for Hispanic, and 42% for Asian patients (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1. Acceptance of emergency department HIV testing among 9,826 patients by race/ethnicity.

aStatistically significant at p<0.05

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Patient perceptions survey

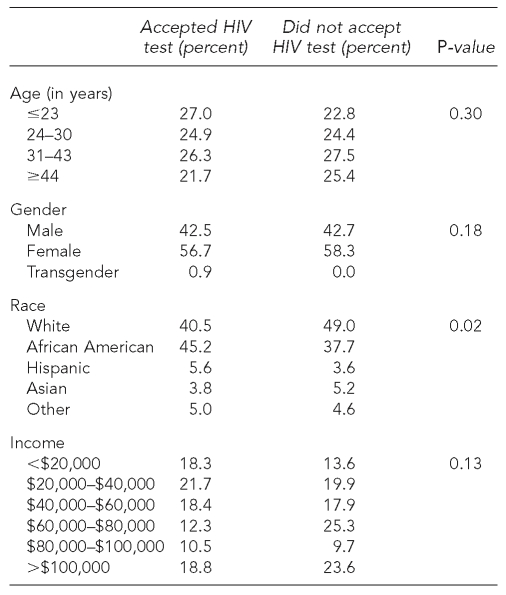

A total of 1,519 completed surveys were returned for analysis. The response rate was not recorded. The mean age of the patients was 34 years (range 14 to 69 years); 54% were men, 40% were women, and 6% were transgender. Nearly one-third (n=520, 34%) earned less than $40,000 a year. Demographic characteristics of the sample by self-reported test acceptance are shown in Table 2. Race was the only variable that was significantly associated with acceptance of the test.

Table 2. Demographics of patients surveyed in the emergency department by self-reported HIV test acceptance.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Almost all patients surveyed (97%) were offered an ED HIV test, and of these, 69% accepted the test. Almost 70% had been tested for HIV on at least one previous occasion, and 14 patients (1%) were already known to be HIV-positive.

Patient attitudes toward ED HIV testing

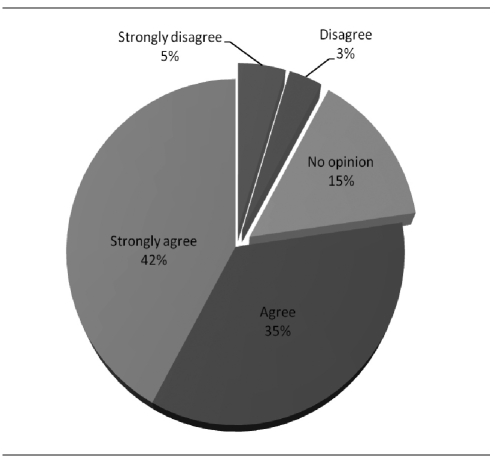

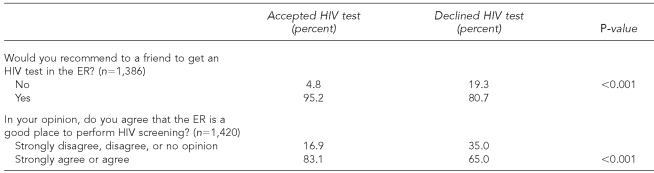

Patients were asked two questions about the suitability of the ED as a venue to get an HIV test: “Would you recommend to a friend to get an HIV test in the ER?” and, “In your opinion, do you agree that the ER is a good place to perform HIV screening?” Of 1,386 responses, 91% reported that they would recommend ED HIV testing to a friend. Of 1,420 responses on whether the ED was a good place for an HIV test, 77% either agreed or strongly agreed, 8% either disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 15% expressed no opinion (Figure 1). Individuals who reported accepting the test were more likely to agree or strongly agree to these two questions than those who did not agree or had no opinion (p<0.001) (Table 3). Among the 485 patients who had never been tested for HIV, a higher proportion accepted the test compared with those who had previously been tested (73% vs. 67%, p=0.02). Similarly, among those who had never been tested, African Americans were significantly more likely to accept HIV testing than other races/ethnicities (85% vs. 70%, p<0.01).

Figure 1. Overall patient responses to the question, “In your opinion, do you agree that the ER is a good place to perform HIV screening?” (n=1,420).

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ER = emergency room

Table 3. Patient perceptions of the suitability of emergency department testing by self-reported test acceptance.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ER = emergency room

Reasons for declining an ED HIV screening test

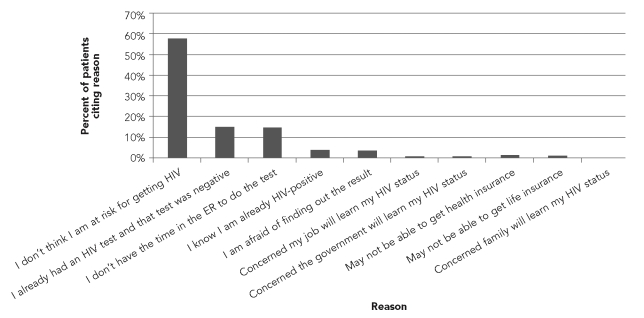

In the surveyed group, 455 patients refused the test, of whom 415 (91%) responded to questions asking why they refused the test (Figure 2). The most common reasons for declining an HIV test were that the patient did not feel at risk (n=247, 60%), the patient had recently had a negative HIV test (n=65, 16%), and there was no time to do the test in the ED (n=63, 15%).

Figure 2. Reasons for declining an emergency department HIV test (n=415).

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ER = emergency room

Compared with all other races/ethnicities, African Americans were less likely to report that they declined the test because they did not feel they were at risk (34.4% vs. 64.3% among other races/ethnicities, p<0.001). Furthermore, among those who refused the test, the self-reported HIV infection prevalence was significantly higher among African Americans than other races/ethnicities (6.1% vs. 0.8%, p=0.002). Even after excluding individuals who self-reported being HIV-positive, African Americans were still less likely to report that they did not feel they were at risk for HIV as a reason for not testing. African Americans were also more likely to have reported recently testing negative as a reason for not testing compared with other races/ethnicities (22.9% vs. 10.0%, p<0.001).

Attitudes of patients who declined an ED HIV test

Among the 455 surveyed patients who declined an ED HIV test, there was a very large measure of support for testing. Of those who expressed an opinion, 80% would recommend to a friend to get an ED HIV test, and 60% either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “the ER is a good place to perform HIV screening” (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Although the CDC recommendations on offering HIV testing to all ED patients aged 13 to 64 years are relatively new, they have proven to be controversial. Advocates have viewed them as a major step in the fight against HIV in the U.S., and have recommended ED HIV screening as a significant public health opportunity.

Several years before the CDC recommendations, the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine had recommended HIV screening in certain settings as “recommended for direct application in the ED setting.”5 Rothman echoed this in an important systematic review of ED HIV screening published in 2004. He noted that “[s]ince EDs provide health care to many underserved and socially marginalized sections of the community, who otherwise have limited or no access to routine preventive health services, development of ED-based HIV screening programs has particular social importance.”6 Others have been critical of the recommendations in general, and of ED HIV screening in particular. Melanie Sovine, executive director of the AIDS Survival Project in Atlanta, opined that “[a]ny policy that suggests you are just testing someone and just giving them a piece of information without support is not going to be well-received by this community.”2 However, our research suggests that in point of fact, the community of those being tested is overwhelmingly supportive of ED HIV testing.

To our knowledge, this is the first large survey of patient perceptions toward ED HIV testing. Hutchinson reported the results of six focus groups at urgent care centers that explored patient perspectives of both rapid and routine HIV testing in an urgent care center at an urban public hospital. Among these groups, the most common reasons for refusing an HIV test (and for not returning for the results) were fear and stigma. In Hutchinson's focus groups, 60% of the participants were uninsured and 89% of the participants were African American.7 In contrast to Hutchinson, our study found that fear and stigma were very rarely given as the reasons for refusing a test. Offering a survey to all patients in the ED is more likely to result in a representative sample of their beliefs, and we believe that the concerns raised by the participants in Hutchinson's study cannot be generalized to the ED population.

In our study, the two most common reasons for declining an HIV test were “not at risk” and “already tested.” These are identical to the two most common reasons for declining an HIV test at urgent care centers reported from Massachusetts,8 although the 67% refusal rate at those centers was considerably higher than the refusal rate at our site. These findings emphasize that perception of risk is the main reason that patients decline an HIV test. Several prior studies have demonstrated that a substantial number of people with HIV infection do not perceive themselves to be at risk for HIV or do not disclose their risks.9–11 This information, together with the findings of both our survey and the one performed in Massachusetts, strongly suggest that patients need to be educated about perception of risk and the realities of HIV infection. For example, EDs that offer HIV testing should provide educational materials about HIV risk factors. This information may help patients better understand their personal risks and may decrease the numbers of patients who decline testing based on perceived risk factors.

Overall, there is a high rate of acceptability of routine ED HIV screening. More importantly, among African Americans—the racial/ethnic group with the greatest burden of HIV disease in the U.S.—the acceptance rate of ED HIV testing is higher than for any other racial/ethnic group. In addition, African Americans were less likely to decline a test because they did not feel at risk, suggesting they may have a higher self-awareness of their HIV risk than other racial/ethnic groups, which is likely to be a factor in their higher acceptance rates.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the study was limited to one urban academic institution in a city that has an ongoing HIV screening campaign. These results will, therefore, need to be validated in other settings. Secondly, this survey represented a convenience sample of the approximately 40,000 patients seen in the ED during the study period. Although a large number of patients were surveyed, we did not collect data on the patients who declined to answer the survey. Individuals who refused to participate in the survey may have different perceptions of ED HIV testing compared with individuals who were willing to answer the survey. Moreover, socially desirable answers may have biased the responses, as ED patients were being surveyed about their perceptions of care in the ED while they were waiting for care. However, the survey was completely anonymous, and participants were informed that their responses would not affect their care in the ED. Third, we did not study all the variables that might affect satisfaction rates, such as knowledge about HIV infection, interaction with the staff offering the test, and concerns about confidentiality. However, this study provided insight on patient perceptions about the acceptability of conducting HIV screening in the ED.

CONCLUSIONS

This study adds important information to the ongoing discussion surrounding ED HIV testing. It provides the first evidence about patient perspectives on the new CDC guidelines, and suggests that ED patients are overwhelmingly in favor and likely to avail themselves of ED HIV testing. In particular, we conclude that:

Most patients will accept an ED HIV test offered to them in the ED as part of routine care.

The rates of acceptance were highest among African Americans, who have the greatest burden of HIV disease.

The most common reason for declining an ED HIV test was the perception of not being at risk for the disease. African Americans were less likely to report this as a reason for declining the test.

More than three-quarters of ED patients believed that the ED was a good place to perform HIV testing, and more than 90% would recommend to a friend to get an HIV test while in the ED.

Dissemination of these results will add some important facts to the debate over the role of ED HIV testing, and these findings suggest that EDs considering introducing this type of testing will be met with overwhelming support from the most important constituents of all—the patients.

Footnotes

The study was funded in part by an unrestricted grant from Gilead Sciences and the HIV/AIDS Administration, Department of Health, Washington, D.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. quiz CE1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna M. HIV testing: should the emergency department take part? Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:190–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, Bahn M, Czarnogorski M, Kuo I, et al. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines: results from a high-prevalence area. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:395–401. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stata Corp. Stata: Version 9.0. College Station (TX): Stata Corp.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babcock Irvin C, Wyer PC, Gerson LW The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Preventive care in the emergency department, part II: clinical preventive services—an emergency medicine evidence-based review. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1042–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothman RE, Ketlogetswe KS, Dolan T, Wyer PC, Kelen GD. Preventive care in the emergency department: should emergency departments conduct routine HIV screening? A systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:278–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutchinson AB, Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Mohanan S, del Rio C. Understanding the patient's perspective on rapid and routine HIV testing in an inner-city urgent care center. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:101–14. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.2.101.29394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liddicoat RV, Losina E, Kang M, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. Refusing HIV testing in an urgent care setting: results from the “Think HIV” program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:84–92. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anonymous or confidential HIV counseling and voluntary testing in federally funded testing sites—United States, 1995–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(24):509–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voluntary HIV testing as part of routine medical care—Massachusetts, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(24):523–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.HIV prevalence, unrecognized infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men—five U.S. cities, June 2004–April 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(24):597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]