Abstract

The lacrimal gland produces secretions that lubricate and protect the cornea of the eye. Foxc1 encodes a forkhead/winged helix transcription factor required for the development of many embryonic organs. Autosomal dominant mutations in human FOXC1 cause eye disorders such as Axenfeld-Rieger Syndrome and glaucoma iris hypoplasia, resulting from malformation of the anterior segment of the eye. We show here that lacrimal gland development is severely impaired in homozygous null Foxc1 mouse mutants, with reduced outgrowth and branching. Foxc1 is expressed in both the epithelium of the lacrimal gland and the surrounding mesenchyme. FGF10 stimulates the growth and branching morphogenesis in cultures of wild type and Foxc1 mutant gland epithelial buds. However, using micromass culture of lacrimal gland mesenchyme, we show that Bmp7 induces wild type mesenchyme cells to aggregate, but Foxc1 mutant cells do not respond. This study demonstrates that Foxc1 mediates the BMP signaling required for lacrimal gland development.

Keywords: Forkhead transcription factor, Foxc1, Branching morphogenesis, Lacrimal gland

Introduction

The lacrimal gland produces secretions that lubricate and protect the avascular cornea. Insufficient tear production results in ocular surface diseases such as dry eye syndromes, which affect about 10 million people in the USA alone (Rios et al., 2005). Sjogrens syndrome is a relatively common autoimmune disorder characterized by dry eyes and mouth that affects both the salivary and lacrimal glands, (Fox, 2005). In severe cases, abnormalities in the lacrimal gland that lead to the absence of corneal lubrication can result in ulceration and blindness (Knop et al., 2003). Despite the prevalence of dry eye syndrome and similar lacrimal gland disorders, relatively little is known about the development and physiology of the lacrimal gland. In the mouse, lacrimal gland development begins at E13.5 with ectodermal budding from the conjunctival fornix at the temporal aspect of the eye. The primary bud extends caudally into the surrounding neural-crest derived mesenchyme. Between E15.5 and E16.5 the bud undergoes branching morphogenesis, forming both a major extra-orbital lobe and a minor intraorbital lobe (Makarenkova et al., 2000). The mature gland is composed of ductal epithelial cells and serous acini surrounded by myoepithelial cells, as well as blood vessels and nerves (Rios et al., 2005).

Several key signaling pathways are involved in lacrimal gland development. Fibroblast growth factor 10 (Fgf10) promotes the proliferation of lacrimal gland epithelium (Makarenkova et al., 2000);(Entesarian et al., 2005), and the transcription factor Pax6 may act as a lacrimal gland competence factor in the conjunctival epithelium (Makarenkova et al., 2000). Bmp7 is expressed in both the epithelial and mesenchymal components of the lacrimal gland and Bmp7 null mutants have reduced lacrimal gland size and branching (Dean et al., 2004). It is thought that Bmp7 acts primarily on the lacrimal gland mesenchyme, promoting mesenchymal proliferation and condensation to regulate branching morphogenesis. Canonical Wnt signaling modulates Fgf10 levels in the mesenchyme and suppresses Bmp-induced proliferation, providing a negative regulation of lacrimal gland branching morphogenesis (Dean et al., 2005).

In this study, we have investigated the role of the forkhead transcription factor, Foxc1, in elongation and branching morphogenesis of the lacrimal gland. Foxc1 homozygous null mouse mutants die perinatally with hemorrhagic hydrocephalus. They also have severe skeletal, cardiovascular and ocular abnormalities, including absent anterior chamber and open eyelids at birth (Kidson et al., 1999);(Kume et al., 1998);(Hong et al., 1999). In her description of the phenotype of Foxc1ch (congenital hydrocephalus) null mutants Green (1970) reported a reduction in lacrimal gland size but this was not investigated further. Here, we show that the Foxc1-/- phenotype is due to reduced outgrowth and branching of the mutant gland both in vivo and in organ culture. We also established that Foxc1 is expressed in both epithelium and mesenchyme. We therefore used cultures of isolated tissues to explore differences in the response of mutant and wild type epithelium and mesenchyme to individual signaling factors known from genetic analysis to regulate lacrimal gland development.

Results

Foxc1 is expressed in the developing lacrimal gland

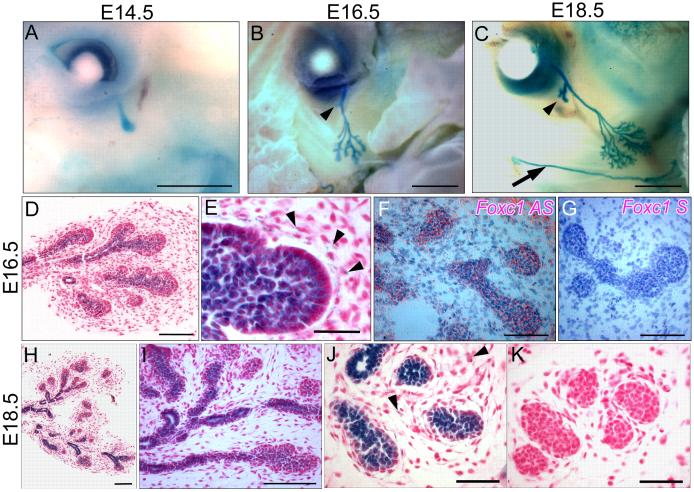

We used immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization to study the expression of Foxc1 in both the elongation and branching phases of lacrimal gland development. We first examined β galactosidase expression in embryos heterozygous for the Foxc1lacZ “knock-in” allele (Figure 1). The lacrimal bud develops from an out budding of the lacZ positive conjunctival epithelium between E13.5-14.5 (Figure 1A). Between E15.5-16.5, when the lacrimal bud begins to branch, both the gland epithelium and mesenchyme is positive for Foxc1lacZ expression (Figure 1B, D, E). As development proceeds through to E18.5, lacZ expression is maintained in both the epithelial buds and the lacrimal duct (Figure 1C, H-J). No lacZ expression is seen in wild type glands (Figure 1K). In these studies low levels of ß-galactosidase activity could be seen in the mesenchyme around the gland under high magnification (Figure 1E, J). We confirmed the expression of Foxc1 using radioactive in situ hybridization of embryo sections. As shown in Figure 1F this clearly demonstrates that both epithelium and mesenchyme contain Foxc1 transcripts. No hybridization is seen in the sense strand control (Figure 1K).

Figure 1.

Foxc1 is expressed in both mesenchyme and epithelium of the developing lacrimal gland. All figures show Foxc1lacZ staining except F and G. (A) Whole mount preparation at E14.5 when the Foxc1 positive lacrimal bud extends from the conjunctival epithelium. (B) At E16.5, branching has begun in the main lobe, and the intraorbital lobe has formed (arrowhead). Foxc1 is expressed in the duct and budding epithelium. (C) At E18.5 Foxc1 expression continues in the epithelium of the main lobe and the less highly branched intraorbital lobe (arrowhead) and parotid gland (arrow). (D and E) Cross sections through lacrimal glands at E16.5 reveal that Foxc1 is expressed in bud and duct epithelium and mesenchyme, especially surrounding the tips of the epithelial buds (arrowheads in E). (F) In situ hybridization with the Foxc1 anti-sense probe reveals high levels of expression in the epithelium and confirms expression in the mesenchyme. (G) No signal is seen with sense strand control. (H-J) Sections through lacrimal glands at E18.5 show expression in both epithelium of the duct and buds, and the mesenchyme (arrowheads). (K) No staining is seen in wild-type samples not containing the lacZ allele. Scale bars = 1 mm (A-C), 100 μm (D, F-I, K), 50 μm (E, J).

Foxc1 is essential for normal morphology of the lacrimal gland

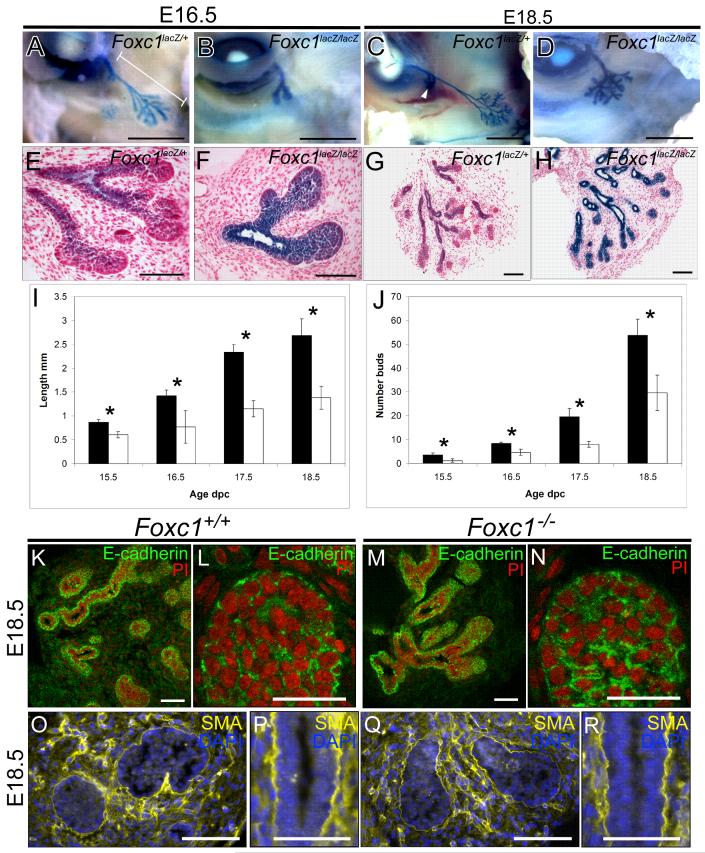

Budding of the lacrimal gland epithelium from the conjunctival epithelium was seen at E13.5 in both wild-type and null mutant Foxc1 embryos. Branching is initiated in the wild type gland between E15.5 and E16.5 from the tip of the lacrimal bud (Figure 2A, E). In Foxc1 mutant glands, branching is also initiated, but the branches appear shorter and wider, and fewer terminal buds are present (Figure 2B, F). By E18.5, the wild-type gland consists of two main lobes; an extensively branched exorbital lobe and a small intraocular lobe derived from a single branch of the proximal duct (Figure 2C, G). By contrast, the lacrimal gland in Foxc1 null embryos shows various abnormalities (Figure 2D, H). The exorbital lobe is severely reduced and the intraorbital lacrimal gland is absent. The lacrimal ducts within the Foxc1 null gland are distended and the individual buds are shorter and wider. Quantification confirms that in the Foxc1 null embryos there is a significant reduction in both the overall length of the gland duct and in the number of terminal buds within the exorbital lobe (Figure 2I and J, n=minimum of 6 glands for each stage *p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Foxc1 is required for normal development of the lacrimal gland. (A and E) At E16.5 Foxc1+/lacZ lacrimal glands have begun branching and extend out from the conjunctival epithelium. (B and F) In comparison, the Foxc1 mutant glands show reduced branching and elongation. Lacrimal buds are thicker and shorter. (C and G) By E18.5, Foxc1+/lacZ lacrimal glands consist of an extensively branched main lobe, and a smaller, intraorbital lobe (arrowhead). (D and H) Foxc1 mutant glands lack an intraorbital lobe and the main lobe has significantly fewer branches. (I) Quantification of the total gland length and (J) number of acini in control (black bars) and Foxc1 mutant (white bars) lacrimal glands. *p<0.05, n = a minimum of 6 in all groups. (K-N) E-cadherin (green staining) is expressed in the epithelial component of the lacrimal gland in both wild type (K and L) and Foxc1 mutant embryos (M and N). Nuclei are counterstained with propidium iodide (red staining). Smooth muscle actin α (yellow staining) is expressed in the mesenchyme in both wild type (M) and Foxc1 mutant (N) lacrimal glands. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue nuclei). Scale bars = 1 mm (A-D), 100 μm (E-H, K, M, O, Q), 50 μm (L, N, P, R).

To further examine the morphology of Foxc1 mutant glands we analyzed two markers expressed in lacrimal gland epithelium and mesenchyme. E-cadherin is expressed within epithelial cells (Figure 2K-N), whilst smooth muscle α-actin is expressed in mesenchyme cells, particularly around terminal epithelial buds and lacrimal ducts (Figure O-R). No significant difference in the pattern or level of expression of these two markers was seen between wild type (Figure 2 K-L, O-P) and Foxc1 mutant glands (Figure 2M-N, Q-R).

Foxc1 is required for branching morphogenesis of the lacrimal gland

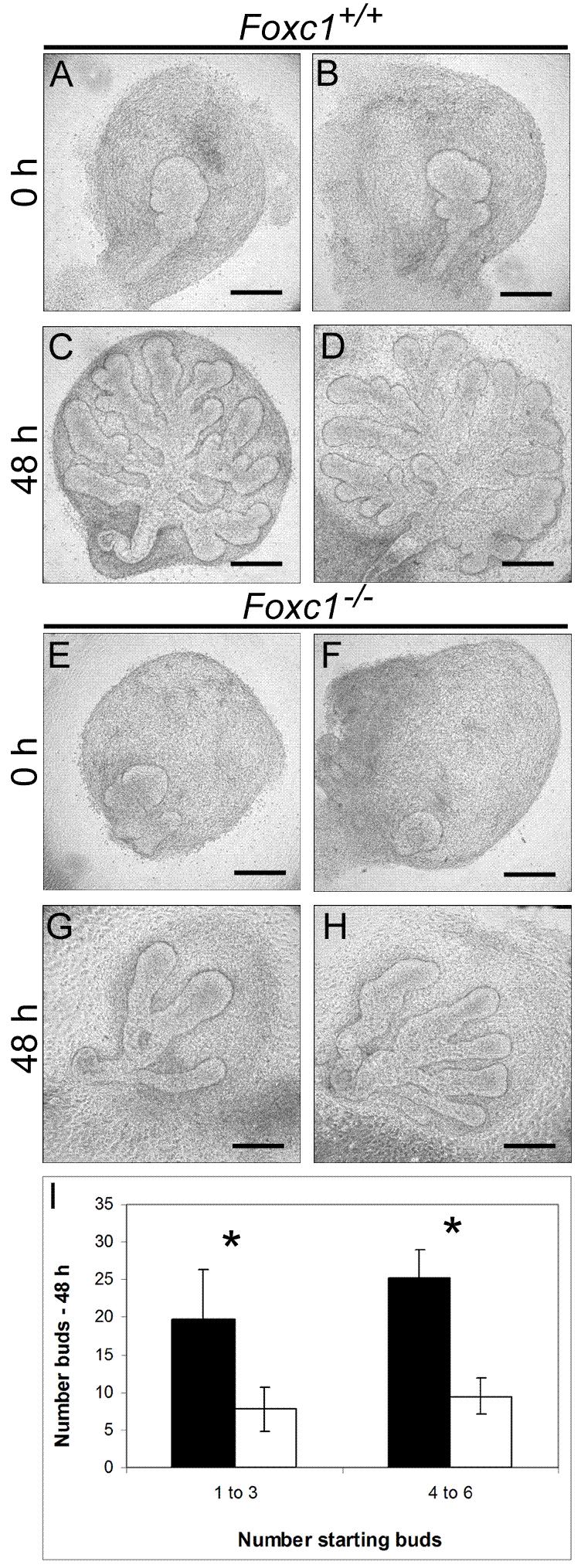

To test whether the Foxc1 mutant phenotype is due to an overall developmental delay or to an intrinsic defect in gland development we cultured whole lacrimal gland explants (epithelium plus mesenchyme) in vitro. This enabled us to compare side-by-side the development of wild type and mutant glands that were initially of the same size and stage. Fewer terminal buds were observed in Foxc1 mutant glands (n=9) after 48 hours compared to wild type (n=19)(Figure 3). Significantly, the individual terminal epithelial buds that did form in Foxc1 null explants were longer and wider than those in the wild-type controls (compare Figure 3C to Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Foxc1 is required for normal branching morphogenesis of the lacrimal gland. Examples of whole lacrimal explants from E15.5 embryos from two different wild type (A-D) or Foxc1 mutants (E-H) that were cultured for 48 hours. At the start of the culture period, glands contained between 1-6 buds. After 48 hours, wild type glands showed extensive branching (C and D). In comparison, Foxc1 mutant glands had fewer branches and individual branches were longer and wider (G and H). (I) Quantification of the increase in bud number from wild type (black bars) and Foxc1 mutant (white bars) lacrimal glands starting from 1-3 or 4-6 buds. Branching is significantly reduced in mutant glands (*p<0.05, n = 9 mutant glands, n = 19 wild type glands). Scale bars = 200 μm (A-H).

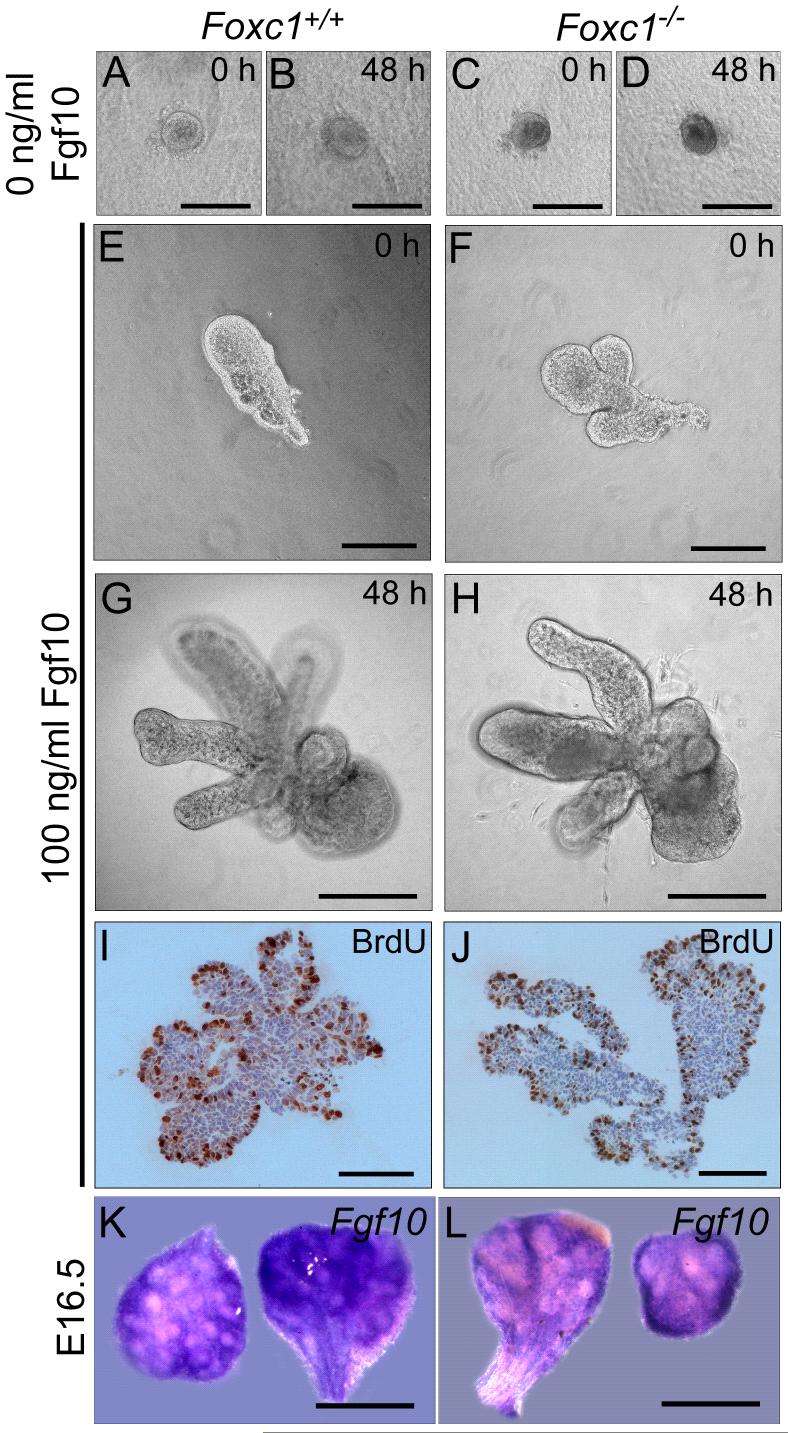

Foxc1 is not required for FGF-induced proliferation of the lacrimal gland epithelium

FGFs are required for the induction of the lacrimal bud, proliferation of the lacrimal gland epithelium and for elongation of the duct (Govindarajan et al., 2000);(Makarenkova et al., 2000). In situ hybridization analysis showed that Fgf10 is expressed in the mesenchyme of both wild type and Foxc1 mutant glands, with no difference in either the pattern or level of expression (Figure 4K and L). To determine if Foxc1 mutant glands were responsive to FGFs, we analyzed the response of isolated epithelium to exogenous FGFs. E15.5 mesenchyme-free primary bud explants were established in growth factor free Matrigel™ droplets and cultured for 48 hours. In the absence of FGF, epithelial buds from both wild type (n=15) and Foxc1 mutant (n=11) lacrimal glands showed little extension or proliferation (Figure 4A-D). The addition of FGF10 to the medium resulted in proliferation of the epithelium, as detected by BrdU labeling (Figure 1I, J). There was no difference in response between wild type (n=20) and Foxc1 mutant (n=17) buds (Figure 4E-J). The buds from both wild type and mutant glands elongated, but showed little secondary budding/branching over the 48 hour time period, confirming results from previous studies (Makarenkova et al., 2000).

Figure 4.

Foxc1 is not required for FGF-induced proliferation of the lacrimal gland epithelium. (A-D) In the absence of FGF, epithelial buds in Matrigel™ droplets from E15.5 wild type (A and B) and Foxc1 mutant embryos (C and D) showed little extension or proliferation. (E-H) The addition of 100 ng/ml FGF10 to the medium resulted in extension of the epithelial buds from both wild type (n=15, E and G) and Foxc1 mutant (n=11, F and H) glands. (I and J) BrdU staining indicates that addition of exogenous FGF10 results in equal proliferation in both wild type (n=20, I) and Foxc1 mutant glands (n=17, J). Cultures were repeated three times for each condition. (K and L) Fgf10 is expressed in the mesenchyme of lacrimal glands in both wild type (K) and Foxc1 (L) null mutants. Scale bars = 100 μm (A-D, I, J), 200 μm (E-H), 500 μm (K, L).

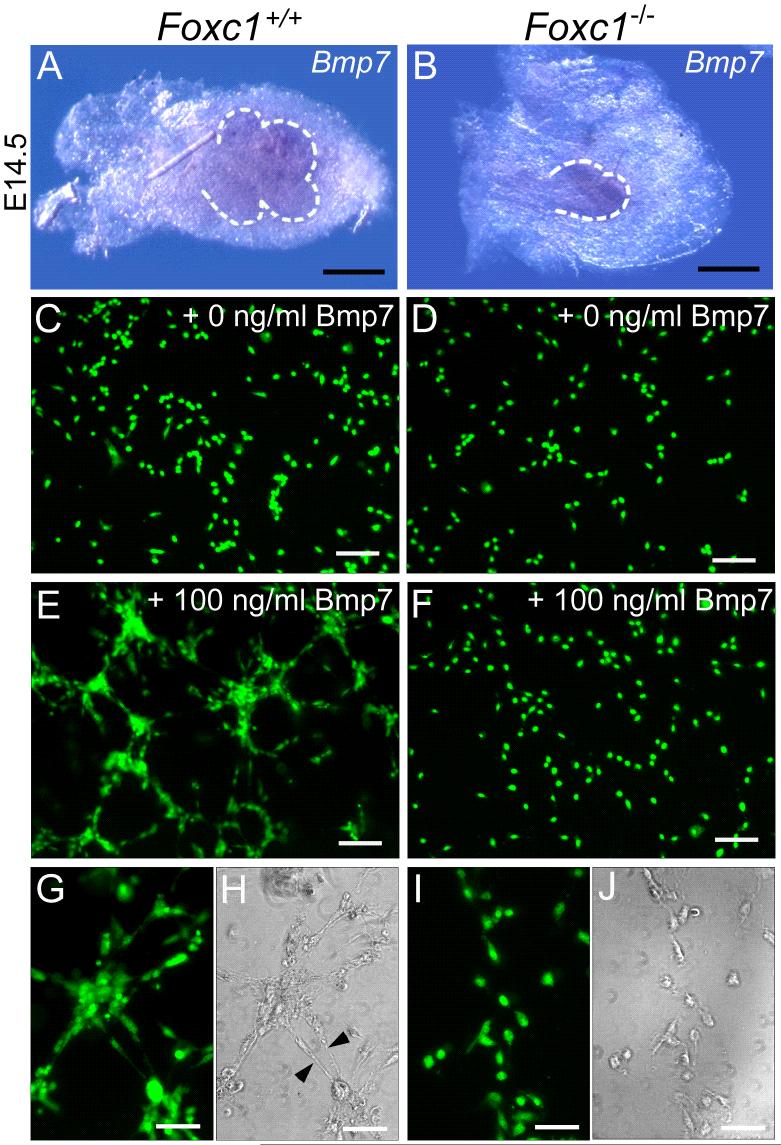

Foxc1 is required for the response of mesenchyme to exogenous Bmp7

Bmp7 is expressed in both the epithelium and mesenchyme of the developing lacrimal gland. Bmp7 null embryos have smaller lacrimal glands that wild type, with fewer terminal buds than normal. Exogenous Bmp7 promotes the proliferation and aggregation of isolated lacrimal gland mesenchyme cells in culture (Dean et al., 2004). We examined the expression of Bmp7 in wild type and Foxc1 mutant glands, and found no difference in the pattern or level of expression (Figure 5A, B). Since Foxc1 mediates Bmp signaling in other tissues (Kume et al., 1998);(Rice et al., 2003);(Rice et al., 2005), and Foxc1 is expressed in lacrimal gland mesenchyme, we hypothesized that Foxc1 functions downstream of Bmp7. We therefore isolated mesenchymal cells from wild type and Foxc1 mutant embryos at E15.5 and analyzed the response of cells to 100 ng/ml Bmp7 in micromass cultures as previously described (Dean et al., 2004)(Figure 5). Without Bmp7, both wild type (Figure 5C, n=3) and Foxc1 mutant (Figure 5D, n=3) mesenchymal cells showed little aggregation over a 48 hour period, and remained evenly distributed over the plating area. Addition of Bmp7 to wild type mesenchymal cells caused changes in cell morphology and distribution (Figure 5E, G, H, n=3). The cells became elongated and after 48 hours had aggregated together to form large clusters. However, the addition of Bmp7 to Foxc1 mutant mesenchymal cells did not induce changes in either cell morphology or distribution (Figure 5F, I, J, n=3).

Figure 5.

Foxc1 is required for the response of mesenchyme to Bmp7. (A and B) Bmp7 is expressed in the epithelium (outlined in dashed lines) and weakly in the mesenchyme of both wild type (A) and Foxc1 mutant (B) glands. (C-F) Isolated mesenchymal cells stained with Syto13. In the absence of Bmp7, wild type (C) and Foxc1 mutant mesenchyme (D) at E15.5 showed little aggregation over a 48 hour period, and remained fairly evenly distributed over the plating area. (E, G, H) Addition of 100 ng/ml Bmp7 to wild type cells caused changes in cell morphology and distribution. After 48 hours, the cells were elongated (arrowheads in H), and had aggregated to form large clusters as visualized by Syto13 staining (G) or phase contrast (H). (F) Addition of Bmp7 did not induce changes in either cell distribution (F) or morphology (I-J) in Foxc1 mutant gland mesenchyme cells. Cultures were repeated three times for each condition with each culture containing cells pooled from three different glands. Scale bars = 200 μm (A-B) 100 μm (D-F), 50 μm (H-J).

Discussion

Several lines of evidence suggest that Foxc1 has an important role in regulating the branching morphogenesis of the lacrimal gland. The appearance of primary buds in all Foxc1 null embryos indicates that the gene is not required during the inductive phases of gland development. However, the subsequent development of mutant glands results in shorter ducts, fewer distal branches, abnormally shaped terminal buds and the complete absence of the intraorbital lobe. We show here that one of the primary defects in the Foxc1 mutant glands is likely to be in the response of the gland mesenchyme to Bmp7, although other primary defects cannot be ruled out at this time.

Foxc1 is not involved in the response of lacrimal gland epithelium to FGF10

Genetic analysis has shown that Fgf10, which is expressed in the mesenchyme, is required for normal lacrimal gland development. FGF10 is sufficient for induction of the lacrimal bud from the conjunctival epithelium (Govindarajan et al., 2000), and in Fgf10 null mice the epithelial component of the lacrimal gland is completely absent (Makarenkova et al., 2000);(Entesarian et al., 2005). Isolated lacrimal bud epithelium responds to FGF10 by proliferating, but without branching morphogenesis, suggesting that the primary action of FGF10 on the epithelium is to stimulate epithelial cell division and outgrowth/elongation. We have shown here that isolated lacrimal bud epithelium from Foxc1 null mice responds as normal to FGF10 with increased proliferation and elongation. In addition, there is no significant difference in the expression of Fgf10 in the lacrimal gland mesenchyme of Foxc1-/- embryos compared with normal. Taken together, these data suggest that Foxc1 is not required for FGF induced proliferation and morphogenesis within lacrimal bud epithelium.

Foxc1 functions in the mesenchyme to mediate responses to Bmp7

Bmp7 is expressed in both the epithelium and mesenchyme of the developing lacrimal gland and Bmp7 null embryos have reduced lacrimal glands (Dean et al., 2004). Whole lacrimal glands exposed to exogenous Bmp7 show an increase in the number of epithelial buds but no response was seen in gland epithelium separated from the mesenchyme. By contrast, exposure of isolated mesenchyme to Bmp7 elicited increased proliferation, aggregation and expression of markers of differentiated cell types (Dean et al., 2004). Here, we have replicated the finding that exogenous Bmp7 leads to aggregation of wild type lacrimal gland mesenchyme in culture. Significantly, however, Foxc1 mutant mesenchyme fails to respond to Bmp signaling. Foxc1 has also been implicated as a mediator of Bmp signaling in other cell types. Mesenchyme cells from Foxc1 mutant embryos differentiate poorly into cartilage in micromass culture and do not respond to factors such as Bmp2 and TGFβ1 that promote chondrogenesis (Kume et al., 1998). The process of chondrogenesis requires cell aggregation and an increase in intercellular adhesion, suggesting that Foxc1 normally mediates the upregulation of these processes in mesenchyme target cells in response to Bmps and TGFβ. Similarly, development of calvarial bones of the skull requires condensation of mesenchymal cells which then proliferate and differentiate into osteoblasts (Rice et al., 2003). Foxc1 regulates BMP-mediated osteoprogenitor proliferation required for the progression of osteogenesis, resulting in the lack of calvarium associated with hydrocephalus in Foxc1 mutants.

Based on these observations, there are two possible non-exclusive models for the role of Foxc1 in the development of the lacrimal gland by mediating Bmp7 signaling within the mesenchyme. Firstly, Bmp7 may promote the aggregation of mesenchymal cells which “invade” terminal epithelial buds in the process known as “clefting”, resulting in branching of the epithelium. This process has been described during branching morphogenesis in the salivary gland, where the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin, made by the aggregating mesenchyme, is essential for cleft formation that initiates epithelial branching (Sakai et al., 2003). In Foxc1 mutants the mesenchyme may not be able to respond to Bmp7 by aggregating and migrating into the epithelial terminal bud to create a fibronectin rich cleft (Sakai et al., 2003). Further experiments are required to test this hypothesis. However, it should be noted that abnormalities in the extracellular matrix have been implicated in other Foxc1 null phenotypes, including development of the trabecular meshwork within the anterior segment of the eye (Smith et al., 2000), and prechondrogenic mesenchyme (Kume et al., 1998).

A second hypothesis is that Bmp signaling may be required to establish signaling centers within the mesenchyme near the bud tips that direct the process of branching. Signaling centers are thought to include both epithelial and mesenchymal cells, where small groups of closely associated cells secrete factors and respond to stimuli, enabling the progression of a single epithelial bud into a multi-branched structure (Hogan, 1999). The proliferation and aggregation of mesenchymal cells are responses characteristic of signaling centers that are critical for branching morphogenesis. Bmp7 may be a component of such signaling centers required for branching of the lacrimal gland (Dean et al., 2004). According to this model, mutant mesenchyme fails to aggregate to create a local source of a second factor that promotes bud outgrowth, chemotaxis and/or branching.

Support for our hypothesis that Foxc1 mediates the response of mesenchyme to Bmps comes from the finding that exposure of whole gland explants to the Bmp inhibitors, noggin and follistatin, produces fewer, larger buds than normal as seen in Foxc1 mutant glands (Dean et al., 2004). This model does not mean that Bmp7 is the only Bmp member active in gland morphogenesis. Bmp4 is likely to be another family member, since Bmp4lacZ expression is seen along the length of lacrimal gland ducts (data not shown). However, both Bmp4 and Bmp2 null mice die before lacrimal gland formation, precluding investigation into the requirement of these Bmps for lacrimal gland development.

In conclusion, Foxc1 mutant lacrimal glands are reduced in both gland size and branching morphogenesis. Although the epithelium is responsive to proliferation cues, Foxc1 mutant lacrimal mesenchymal cells do not respond in culture to exogenous Bmp. Taken together, these results suggest that Foxc1 is crucial for mediating Bmp signaling required for normal branching morphogenesis within the lacrimal gland.

Experimental procedures

Animals

Mice heterozygous for the null mutation Foxc1lacZ were maintained by interbreeding on the Black Swiss background and genotyped as previously described (Kume et al., 1998). Noon on the day of plug was E0.5.

Histological analysis

Lacrimal glands were fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight and embedded in paraffin wax. Samples were sectioned at 7 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or nuclear fast red.

β-Galactosidase expression

Whole heads from E15.5 to E18.5 were dissected in PBS and transferred to 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1 h at 4°C. Samples were then rinsed in wash buffer (2 mM MgCl2, 0.02% Nonidet P-40 in PBS) and incubated in lacZ stain (1 mg/ml X-gal, 200 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 200 mM K4Fe(CN)6) at 37°C overnight. After staining, samples were rinsed in wash buffer and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C. At least six glands were examined for each stage from both wild type and Foxc1 mutant embryos.

Quantification

The length of the lacrimal gland from the temporal fornix of the conjunctiva to the most distal end of the epithelial component of the gland (Figure 2A) was measured using Image J (NIH). The degree of lacrimal gland development in explants and in vivo was quantified by counting the number of terminal epithelial buds. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. All error bars shown represent 2x standard error.

Lacrimal gland explant cultures

Whole gland explant cultures were prepared from embryos at embryonic days (E) 15.5. Wild type (n=19) and mutant (n=9) lacrimal glands were excised and placed on Millicell membranes (0.4 μm, Millipore, Cat# PICMORG50) precoated with Collagen Type IV (BD). Glands were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 /air in growth medium consisting of DMEM/F12 (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 5% BSA (Sigma), glutamine (Gibco BRL), non-essential amino acids (Gibco BRL), 1% lipid concentrate (Gibco BRL, Cat# 11905), insulin, selenium and transferrin (Gibco BRL) and penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco BRL).

Culture of isolated lacrimal gland epithelium

Lacrimal gland epithelium was isolated and cultured essentially as previously described (Makarenkova et al., 2000). Briefly, whole glands from E15.5-16.5 embryos were placed in 0.5% trypsin in Tyrode Ringers solution for 25 minutes on ice and dissected in DMDM/F12 medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Isolated epithelium buds were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 5% BSA, glutamine (Gibco BRL), non-essential amino acids (Gibco BRL), 1% lipid concentrate (Gibco BRL), insulin, selenium and transferrin mix (Gibco BRL), EGF (BD, 100 ng/ml) and penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco BRL). Briefly, the tips of developing buds were cultured in droplets of growth factor reduced Matrigel™ (BD) diluted 1:1 in medium, in defined medium alone, or defined medium supplemented with FGF10 (BD, 100 ng/ml). Cultures were repeated three times with at least three epithelial buds for each condition from both wild type and Foxc1 mutant lacrimal glands. At the end of the culture period, epithelial buds were rinsed in PBS and incubated with BrdU (1:1000, Amersham) for 90 minutes at 37°C.

Mesenchyme cultures

Lacrimal gland mesenchyme cultures were prepared essentially as previously described (Dean et al., 2004). Lacrimal glands were isolated from E15.5 embryos and placed in 0.5% trypsin in Tyrode Ringers solution on ice for 1 hour. The tissue was then placed in medium containing serum and the epithelium was mechanically separated from the surrounding mesenchyme using fine needles. The mesenchyme was triturated and pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 g for 5 minutes. Cells were resuspended in defined medium alone or in defined medium plus 100 ng/ml Bmp7 (R&D Systems). 10 μl droplets were cultured on fibronectin (100 μg/ml, Sigma) or Matrigel™ (BD) coated 35 mm tissue culture dishes under paraffin oil. After 48-72 hours culture the cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% PFA for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were rinsed in PBS and stained with Syto13 (Molecular Probes) at 1:1000 in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature. Mesenchymal cells from three lacrimal glands were pooled for each treatment and the cultures repeated three times.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue for immunohistochemistry was fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight, washed in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST), embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 7 μm. Sections were blocked in 3% BSA, 10% serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1h before staining with antibodies. Primary antibodies used were E-cadherin (Zymed, 1:200), BrdU (Sigma, 1:500) and smooth muscle α-actin (SMA)(Sigma, 1:200) after antigen retrieval with 1.25 g/ml trypsin at room temperature for 5 min for both BrdU and SMA. Samples were incubated in the primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescent conjugated antibodies from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA) were used as secondary antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. E-cadherin and SMA sections were counterstained with propidium iodide (0.5 μg/ml) and DAPI (1:5000) respectively. For BrdU, secondary incubations were with biotinylated antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at 1:200-1:250 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Signal was amplified by using streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector, Burlingame, CA) and visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector). Tissues were counterstained with hematoxylin.

In situ hybridization

Whole mount in-situ hybridization was performed essentially as described (Wilkinson and Nieto, 1993). Probes used were Fgf10 (584 bp, (Bellusci et al., 1997)) and Bmp7 (1200 bp, a kind gift from B. Capel).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Blanche Capel for the Bmp7 probe, Tim Oliver for assistant with microscopy and members of the Hogan lab for generous discussion and advice.

Grant sponsor: NIH (Fogarty), Grant number: IR03TW001392-01

References

- Bellusci S, Grindley J, Emoto H, Itoh N, Hogan BL. Fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and branching morphogenesis in the embryonic mouse lung. Development. 1997;124:4867–4878. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C, Ito M, Makarenkova HP, Faber SC, Lang RA. Bmp7 regulates branching morphogenesis of the lacrimal gland by promoting mesenchymal proliferation and condensation. Development. 2004;131:4155–4165. doi: 10.1242/dev.01285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean CH, Miller LA, Smith AN, Dufort D, Lang RA, Niswander LA. Canonical Wnt signaling negatively regulates branching morphogenesis of the lung and lacrimal gland. Dev Biol. 2005;286:270–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entesarian M, Matsson H, Klar J, Bergendal B, Olson L, Arakaki R, Hayashi Y, Ohuchi H, Falahat B, Bolstad AI, Jonsson R, Wahren-Herlenius M, Dahl N. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor 10 are associated with aplasia of lacrimal and salivary glands. Nat Genet. 2005;37:125–127. doi: 10.1038/ng1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RI. Sjogren’s syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:321–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan V, Ito M, Makarenkova HP, Lang RA, Overbeek PA. Endogenous and ectopic gland induction by FGF-10. Dev Biol. 2000;225:188–200. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC. The developmental effects of congenital hydrocephalus (ch) in the mouse. Dev Biol. 1970;23:585–608. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(70)90142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BL. Morphogenesis. Cell. 1999;96:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong HK, Lass JH, Chakravarti A. Pleiotropic skeletal and ocular phenotypes of the mouse mutation congenital hydrocephalus (ch/Mf1) arise from a winged helix/forkhead transcriptionfactor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:625–637. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidson SH, Kume T, Deng K, Winfrey V, Hogan BL. The forkhead/winged-helix gene, Mf1, is necessary for the normal development of the cornea and formation of the anterior chamber in the mouse eye. Dev Biol. 1999;211:306–322. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop E, Knop N, Brewitt H. Dry eye disease as a complex dysregulation of the functional anatomy of the ocular surface. New concepts for understanding dry eye disease. Ophthalmologe. 2003;100:917–928. doi: 10.1007/s00347-003-0935-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume T, Deng KY, Winfrey V, Gould DB, Walter MA, Hogan BL. The forkhead/winged helix gene Mf1 is disrupted in the pleiotropic mouse mutation congenital hydrocephalus. Cell. 1998;93:985–996. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarenkova HP, Ito M, Govindarajan V, Faber SC, Sun L, McMahon G, Overbeek PA, Lang RA. FGF10 is an inducer and Pax6 a competence factor for lacrimal gland development. Development. 2000;127:2563–2572. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice R, Rice DP, Olsen BR, Thesleff I. Progression of calvarial bone development requires Foxc1 regulation of Msx2 and Alx4. Dev Biol. 2003;262:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice R, Rice DP, Thesleff I. Foxc1 integrates Fgf and Bmp signalling independently of twist or noggin during calvarial bone development. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:847–852. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios JD, Horikawa Y, Chen LL, Kublin CL, Hodges RR, Dartt DA, Zoukhri D. Age-dependent alterations in mouse exorbital lacrimal gland structure, innervation and secretory response. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:477–491. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Larsen M, Yamada KM. Fibronectin requirement in branching morphogenesis. Nature. 2003;423:876–881. doi: 10.1038/nature01712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RS, Zabaleta A, Kume T, Savinova OV, Kidson SH, Martin JE, Nishimura DY, Alward WL, Hogan BL, John SW. Haploinsufficiency of the transcription factors FOXC1 and FOXC2 results in aberrant ocular development. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1021–1032. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.7.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG, Nieto MA. Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:361–373. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]