Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is one of the leading causes of infant hospitalization and a major health and economic burden worldwide. Infection with this virus induces an exacerbated innate proinflammatory immune response characterized by abundant immune cell infiltration into the airways and lung tissue damage. RSV also impairs the induction of an adequate adaptive T cell immune response, which favors virus pathogenesis. Unfortunately, to date there are no efficient vaccines against this virus. Recent in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that RSV infection can prevent T cell activation, a phenomenon attributed in part to cytokines and chemokines secreted by RSV-infected cells. Efficient immunity against viruses is promoted by dendritic cells (DCs), professional antigen-presenting cells, that prime antigen-specific helper and cytotoxic T cells. Therefore, it would be to the advantage of RSV to impair DC function and prevent the induction of T cell immunity. Here, we show that, although RSV infection induces maturation of murine DCs, these cells are rendered unable to activate antigen-specific T cells. Inhibition of T cell activation by RSV was observed independently of the type of TCR ligand on the DC surface and applied to cognate-, allo-, and superantigen stimulation. As a result of exposure to RSV-infected DCs, T cells became unresponsive to subsequent TCR engagement. RSV-mediated impairment in T cell activation required DC-T cell contact and involved inhibition of immunological synapse assembly among these cells. Our data suggest that impairment of immunological synapse could contribute to RSV pathogenesis by evading adaptive immunity and reducing T cell-mediated virus clearance.

Keywords: immunological synapse, virus evasion, virulence mechanism, adaptive immunity

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the worldwide leading cause of infant hospitalization related to airway diseases. RSV infects >70% of children in the first year of life and by age 2, almost 100% of children have been infected at least once with this virus (1, 2). In addition, RSV reinfection is extremely frequent, suggesting that naturally acquired adaptive immunity to RSV is either inefficient or transient (2–4). It is thought that clearance of RSV would require the induction of a balanced Th1/Th2 adaptive immune response capable of inducing the production of neutralizing antibodies and IFN-γ-secreting cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (CTLs) (5, 6). However, RSV-specific T cell responses generally fail to efficiently clear infection (7–9). Although functional RSV-specific memory CTLs and helper T cells can be observed in the blood and spleens of infected hosts, these cells show impaired effector function in infected lung tissues (10–14).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are ubiquitous professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) found in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues, where they locate strategically to capture antigens and present them to T cells as peptides bound to either MHC class I or II molecules (15, 16). These features render DCs as key components for the initiation and modulation of T cell immunity against pathogens, such as virus. Thus, several virulent microorganisms have developed molecular mechanisms to impair DC function and prevent clearance by adaptive immunity (17–21). RSV infection causes a significant increase in the number of mature DCs in mouse lungs (22, 23) and has the capacity to infect and replicate within these cells (24–27), rendering them inefficient at inducing proliferation and IFN-γ secretion by antigen-specific T cells (24, 25). Inhibition of T cell activation by RSV has been suggested to be mediated by soluble molecules secreted by RSV-infected DCs, which reduce their capacity to induce IFN-γ secretion by T cells (28). Although recent data indicate that RSV-induced secretion of IFN-λ and -α by human DCs can impair T cell activation (29), this phenomenon could also be observed upon T cell culture with RSV particles or cells expressing RSV antigens on their surface (30, 31). However, whether RSV-mediated inhibition applies to cognate pMHC recognition by T cells and the mechanism responsible for this inhibition remain unknown.

Here, we have approached these questions by evaluating the effect of RSV infection on the capacity of murine DCs to activate T cells. We observed that DCs are efficiently infected by RSV and, although these cells mature upon infection, they are rendered unable to promote T cell activation in response to cognate-, allo-, and superantigen stimuli. Upon exposure to RSV-infected DCs, T cell proliferation and IL-2 secretion were significantly impaired, and T cells became unresponsive to subsequent stimulation with anti-CD3ε. Inhibition was not mediated by IL-10, and neither seemed to be mediated by soluble factors, because supernatants from RSV-infected DCs failed to impair anti-CD3ε-induced T cell activation. Furthermore, laser confocal microscopy experiments indicated that immunological synapse (IS) assembly between RSV-infected DCs and T cells was completely suppressed, consistent with the notion that RSV-mediated inhibition might require DC-T cell contact. These results support blockade of IS assembly as a novel RSV virulence mechanism, which is likely to contribute to host pathogenesis by evading adaptive immunity and reducing T cell-mediated virus clearance.

Results

DC Maturation and Cytokine Secretion in Response to RSV.

To assess the effect of RSV on immature murine DCs, we first evaluated DC infection by RSV and UV-inactivated RSV (UV-RSV). Surface expression of RSV F protein was measured 48 h postinfection at a multiplicity of infection equal to 1, with three different antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1A, a significant increase on the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) derived from the staining with an anti-F antibody was observed only for RSV-infected DCs. In these assays, the entire DC population displayed an increase on the F-derived fluorescence, which suggests that the majority of DCs are infected by the virus. These data indicate that, upon RSV challenge, the DC population contains cells showing a normal distribution of F protein surface expression (Fig. 1A). In contrast, DCs pulsed with UV-RSV showed no significant antibody staining (Fig. 1A). Further analysis by real-time PCR confirmed the data obtained by flow cytometry, because RSV-pulsed DCs expressed considerable amounts of RSV nucleocapsid RNA contrarily to UV-RSV-pulsed DCs (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

RSV infects murine DCs. DCs were incubated overnight with RSV at a moi equal to 1 and analyzed 48 h later for RSV infection. (A) DC surface expression of RSV F protein. Left shows a representative flow cytometry histogram for F protein expression on the surface of RSV- and UV-RSV-pulsed DCs. As a control, uninfected DCs were included. Right shows the mean fluorescence intensity for RSV F protein staining in DCs. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments, **, P < 0.01. (B) Real-time PCR detection of RSV nucleocapsid transcripts in DCs. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Next, the effect of RSV infection over DC maturation was evaluated. Fig. 2A shows surface expression of CD40, CD80, CD86, MHC-I (H-2Kb), and MHC-II (I-Ab) in untreated, RSV-, UV-RSV-, and LPS-pulsed DCs. Up-regulation was observed for all of the assessed surface markers 48 h post-RSV infection (Fig. 2A). On the contrary, UV-RSV induced no significant up-regulation of maturation markers on DCs. These data are consistent with previous reports in human and murine DCs and support the notion that RSV replication might be required for DC maturation (25, 32).

Fig. 2.

RSV induces DC maturation and cytokine secretion. RSV-induced DC maturation requires viable virus. (A) Uninfected, LPS-, RSV-, or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs at a moi equal to 1 were analyzed 48 h after pulse for surface expression of maturation markers CD40, CD80, and CD86 and MHC-I (H-2Kb) and MHC-II (I-Ab) by flow cytometry. Bar graphs show fold increases for mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) relative to uninfected DCs. Data are means ± of six independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001. (B) DC secretion of IL-6, IL10, IL-12p70, and TGF-β cytokines was assessed 48 h after pulse by ELISA in the supernatants of treated cells. Data are means ± SEM of six independent experiments. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001.

To further characterize the DC response to RSV, secretion of cytokines IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and TGF-β by virus-infected cells was analyzed. These cytokines contribute to define T cell phenotypes resulting from DC-T cell interactions. Although RSV infection led to a significant increase of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by DCs, no increase was observed for IL-12 or TGF-β. DCs treated with LPS, an inducer of IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12, were included as control. Our results are consistent with similar experiments performed on human DCs (24, 25).

RSV Infection Impairs T Cell Activation by DCs.

To determine whether RSV infection can modulate the capacity of DCs to activate naïve T cells, we performed a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) on RSV-infected DCs. T cell activation was determined by measuring IL-2 secretion in response to increasing numbers of control or RSV-infected DCs. A strong inhibition of IL-2 secretion was observed for T cells stimulated with RSV-pulsed DCs, as compared with T cells challenged with unpulsed or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs, which secreted significant amounts of IL-2 (Fig. 3A). RSV failed to inhibit the capacity of DCs to activate T cells in the presence of RSV neutralizing antibodies [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1)]. These data support the notion that RSV is responsible for the observed inhibition of DC function and T cell activation.

Fig. 3.

RSV-infected DCs show an impaired capacity to prime T cells. (A and B) IL-2 secretion, (C and D) CD4 expression and proliferation, and (E and F) surface expression of activation markers CD69 and CD25 was determined for T cells stimulated with allogenic DCs (A, C, and E) or for OT-II T cells stimulated with pOVA-pulsed DCs (B, D, and F), by using uninfected, RSV- or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs. Proliferation was determined by CFSE dilution within the CD4high T cell population. Data are means ± SEM of four to five independent experiments, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001 compared with uninfected treatment in A and B.

To exclude any potential cytotoxicity caused by the RSV pulse, DC and T cell viability was assessed before, during, and after all cocultures. Trypan blue exclusion and flow cytometry vital staining showed no significant cell death during all of the experiment period (data not shown).

In addition to IL-2 secretion, T cell proliferation was determined by carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution assays in response to allogenic DCs. Because activated T cells up-regulate surface expression of CD4 upon antigen recognition (33, 34), CFSE dilution was analyzed for the CD4high alloreactive T cell population. Consistent with the IL-2 secretion data, the CD4high population was significantly reduced in T cells stimulated with RSV-infected DC, as compared with T cells challenged with unpulsed DCs or DCs pulsed with UV-RSV (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, although significant proliferation evidenced as CFSE staining dilution was observed for the CD4high population of T cells stimulated with unpulsed or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs, no CFSE dilution was observed for T cells stimulated with RSV-pulsed DCs (Fig. 3C). A similar pattern was observed when T cell activation markers CD69 and CD25 were determined on the surface of T cells. Although these markers were poorly expressed on the surface of T cells stimulated with RSV-infected DCs, significant expression was observed for T cells challenged with untreated or UV-RSV-treated DCs, which defined a distinct activated CD4+ T cell population (Fig. 3E).

In agreement with the MLR data, activation of CD4+ OT-II T cells with antigen-pulsed DCs was inhibited by RSV infection. To avoid possible variations in antigen processing and presentation between the different treatments, antigen-specific cocultures were performed in the presence of exogenously added antigenic peptide (pOVA). Under these conditions, all three T cell activation parameters, IL-2 secretion, CFSE dilution and CD69 up-regulation, were significantly suppressed when OT-II T cells were stimulated with RSV-infected pOVA-pulsed DCs (Fig. 3 B, D, and F). Equivalent inhibition was observed for T cell activation in response to superantigen-pulsed DCs (data not shown). In contrast, stimulation with pOVA-pulsed uninfected or UV-RSV-treated DCs led to full OT-II T cell activation (Fig. 3 B, D, and F). The notion that impairment of DC function was limited to RSV-infected cells was supported by the observation that pOVA-pulsed uninfected DCs were able to prime OT-II cells in the presence of RSV-infected DCs (SI Text, Fig. S2).

Upon RSV challenge, T cells showed no signs of infection and failed to express viral antigens on their surface (data not shown). Further, RSV caused no significant reduction on pOVA loading on MHC molecules, as shown by binding of FITC-labeled pOVA to DCs (Fig. S3).

RSV Suppression of T Cell Activation Is Not Mediated by DC-Derived Soluble Factors.

It has been described that IL-10 can downmodulate T cell activation by antigen-loaded APCs, which can be partially or totally prevented with blocking antibodies (35, 36). Thus, we evaluated whether the IL-10 secreted by DCs in response to RSV could be responsible for the inhibition of T cell activation; IL-10 activity was blocked with a neutralizing antibody during the DC-T cell cocultures. As shown in Fig. 4 A and B, IL-10 blockade failed to prevent RSV-mediated suppression of T cell activation in MLR and OT-II assays.

Fig. 4.

T cell activation impairment by RSV-infected DC is not mediated by IL-10. (A) IL-2 release by T cells stimulated with allogenic DCs or (B) OT-II T cells stimulated with pOVA-pulsed DCs in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml of a neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody. Data are means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To assess whether the suppression of T cell activation could be mediated by other soluble factors secreted by DCs in response to RSV, T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε antibody in the presence of supernatants obtained from RSV-infected DCs. After 24 h, significant IL-2 secretion was observed for T cells treated with supernatants from either control, RSV-, or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, supernatants obtained from RSV- or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs led to a significant increase in IL-2 secretion by T cells in response to anti-CD3ε, as compared with supernatants from unpulsed DCs. These data suggest that T cell activating factors are present in supernatants recovered from RSV-pulsed DCs. Similar results were observed when transgenic antigen-specific CD4+ OT-II T cells were used (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

T cell activation impairment by RSV-infected DC is not predominantly mediated by soluble factors secreted by DCs. (A) IL-2 release by polyclonal T cells or (B) OT-II T cells in response to plate-bound anti-CD3ε, in the presence of supernatants obtained from uninfected, RSV-, or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs. Data are means ± SEM of at least two independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.0001.

Interaction with RSV-Infected DCs Renders T Cells Unresponsive to Subsequent TCR Engagement.

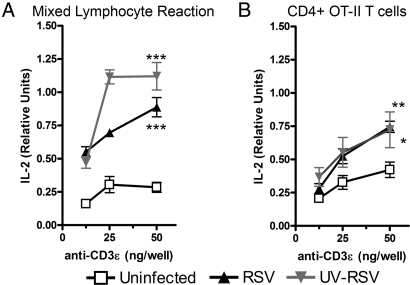

To distinguish whether RSV caused a transient or permanent suppression of T cell activation, plate-bound anti-CD3ε was used to stimulate T cells obtained from cocultures with RSV-infected DCs. As shown in Fig. 6A, T cells derived from MLRs cocultured for 48 h with RSV-infected DCs, failed to secrete IL-2 in response to later stimulation with anti-CD3ε-coated plates. In contrast, T cells that were cocultured with untreated or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs secreted significant amounts of IL-2 in response to plate-bound anti-CD3ε (Fig. 6A). Similarly, OT-II T cells cocultured with RSV-infected DCs were also unresponsive to anti-CD3ε stimulation (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that RSV-infected DCs can confer an anergic-like phenotype to T cells that renders them unresponsive to a strong stimulus, such as anti-CD3ε.

Fig. 6.

Interaction with RSV-infected DCs renders T cells unresponsive to subsequent stimulation with anti-CD3ε. T cells recovered from 48-h cocultures with (A) allogenic DCs or (B) pOVA-pulsed DCs were seeded over plate-bound anti-CD3ε. IL-2 secretion derived from T cells was measured 24 h later in the supernatants. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

RSV Impairs DC-T Cell Synapse Assembly.

Encounter of cognate pMHC complexes on the surface of APCs by T cells triggers the assembly of a specialized structure at the APC-T cell interface, known as the immunological synapse (IS) (37–39). This process involves the reorganization of membrane and intracellular signaling molecules in the T cell, leading to polarization of its secretory machinery toward the APC (38–40). This event is necessary for efficient T cell activation and function (40–43). An important morphological parameter associated with IS assembly is the polarization of the Golgi apparatus in T cells (44). Because soluble factors derived from RSV-infected DCs failed to suppress T cell activation, we tested whether DC-T cell synapse formation was altered by RSV infection. Using laser confocal microscopy, DC-T cell IS assembly was assessed by measuring polarization of Golgi apparatus in OT-II transgenic T cells stimulated with either pOVA-loaded control, RSV-infected, or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs. As shown in Fig. 7, Golgi apparatus polarization within T cells cocultured with RSV-infected DCs was barely detectable and reduced to a background frequency equivalent to that of T cells cocultured with unpulsed (no peptide) DCs (Fig. 7 and Movies S1–S11). In contrast, T cells cocultured with control or UV-RSV-infected DCs showed significant Golgi apparatus polarization, which suggests IS assembly upon cognate ligand recognition (Fig. 7 and Movies S1–S11). These data would support impairment of IS assembly as the mechanism responsible for the suppression of T cell activation by DCs infected with RSV.

Fig. 7.

Immunological synapse assembly between DCs and T cells is impaired by RSV. Uninfected, RSV-, or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs (red fluorescence) were cocultured with transgenic OT-II T cells (green fluorescence). Polarization of the Golgi apparatus of T cells was determined by laser confocal microscopy. (A) One representative microphotograph per treatment is shown (Scale bar, 5 μm). Arrowheads show Golgi apparatus (green fluorescence) polarization from T cells toward a DC (red fluorescence). (B) Quantification of T cells with Golgi apparatus polarization toward DCs within total DC-T cell conjugates. Data are means ± SEM of at least 800 visualized DC-T cell conjugates obtained from 50 fields per treatment, captured in three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.0001.

Although RSV infection led to a significant impairment on IS assembly between infected DCs and T cells, the virus did not alter the efficiency of DC-T cell conjugate formation and ICAM-1 polarization in those conjugates (Figs. S4 and S5). Furthermore, when T cells were simultaneously stimulated with uninfected or UV-pulsed DCs together with RSV-infected DCs, significant IS polarization toward uninfected DCs was observed (Fig. S6 and Movies S1–S11). These data are consistent with the T cell activation data described above, suggesting that impairment of DC function was limited to RSV-infected (SI Text, Fig. S2).

Discussion

DCs are essential for the activation and modulation of T cell immunity against viruses. The importance of DCs during RSV infection was recently underscored by the observation that depletion of plasmacytoid DCs in mice impairs virus clearance and exacerbates the immune-mediated pathology caused by the virus (22, 45). However, despite their beneficial role against RSV, DCs can be infected with the virus and possibly become targets for immune evasion and adverse modulation of T cell function by this pathogen. In the present study, we have provided data indicating that murine DCs are readily infected by RSV, which promotes their maturation. However, DC maturation was observed only in response to viable RSV and not UV-inactivated RSV, which would suggest that induction of DC maturation would need viral replication (25, 32). In agreement with other reports, we observed significant secretion of IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by DCs infected with RSV (25, 26).

In addition, and consistent with previous studies (24, 25, 28, 29), we observed significant impairment in the capacity of DCs to induce T cell activation. Interestingly, here we show that suppression of DC function by RSV was independent of the nature of the TCR-ligand and applied to RSV-infected DCs presenting either allo-, cognate-, or superantigens to T cells.

Previous reports suggested a role for soluble molecules, such as IFN-α and -λ secreted by RSV-infected human DCs in T cell inhibition (29). Here, we assessed a potential role for molecules secreted by murine DCs in response to RSV over inhibition of T cell activation. We observed that neither DC-derived IL-10 nor total supernatants from RSV-infected DCs were able to suppress T cell activation by DCs or plate-bound anti-CD3ε. In contrast, T cells treated with supernatants obtained from RSV- or UV-RSV-pulsed DCs secreted significantly more IL-2 in response to anti-CD3ε than controls. These results suggest that supernatants from RSV-infected DCs not only fail to inhibit but also promote T cell activation, possibly because of the presence of T cell stimulating cytokines.

Taken together, our observations support the notion that T cells acquire an unresponsive phenotype equivalent to anergy, as a result of contact-dependent cell interactions with RSV-infected DCs. It is known that modulation of IS assembly between T cells and DCs can lead to a blockade of productive and sustained TCR signaling required for T cell activation, thus altering T cell function and responsiveness to stimulation via TCR engagement (38, 41–43, 46–48). The importance of IS assembly for T cell function is underscored by recent observations indicating that pathogens have evolved molecular mechanisms to prevent IS formation and impair the initiation of adaptive immunity (41–43, 46, 48). Upon assessment of IS assembly, we observed a significant decrease in the polarization of T cell Golgi apparatus toward DCs infected with RSV. Impairment of IS formation by RSV could provide an explanation for the ability of the virus to keep DCs from activating several effector functions in T cells, such as IL-2 secretion, proliferation, and up-regulation of surface activation markers. Thus, it is likely that interference with IS assembly is directly involved in RSV-mediated T cell inhibition. The virulence mechanism described here for RSV is consistent with the observation that mitogen-induced human T cell activation can be inhibited by this virus (30, 31).

Taken together, our results strongly suggest that T cell inhibition by RSV-infected DCs is significantly mediated by direct DC-T cell contact and more specifically through IS interference. These data suggest that RSV has evolved molecular mechanisms to impair T cell activation by murine DCs directly through abolition of IS assembly. Interference with IS function could account, at least to some extent, for the inappropriate and inefficient adaptive immune responses developed against RSV in vivo (10–14). Our findings contribute to the understanding of how RSV modulates adaptive immunity in the host and highlight the need for further characterization of the interaction between T cells and RSV-infected DCs.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 and BALB/c wild-type mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The OT-II transgenic mouse strain (49) expressing a specific TCR for I-Ab/OVA323-339, was obtained from R. Steinman (The Rockefeller University, New York). All mice were maintained and manipulated according to institutional guidelines at the pathogen-free facility of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Virus Preparation.

HEp-2 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were used to propagate RSV serogroup A, strain 13018–8 (clinical isolate obtained from the Insituto de Salud Pública de Chile), as described in SI Text. UV-RSV was obtained exposing 2 ml of ice-packed virus preparations vials for 45 min over a 302-nm 15-W lamp transiluminator.

Real-Time PCR Detection of RSV.

Total RNA was isolated from 4 × 106 DCs unpulsed or pulsed overnight either with RSV or UV-RSV at a moi equal to 1 by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription-PCR (ImProm-II, Promega) was performed with the use of random primers followed by RSV nucleocapsid N-gene quantitative RLT-PCR (Brilliant QPCR Master Mix, Stratagene) on an Mx3000P thermocycler (Stratagene). Data are expressed as the number of RSV N-gene transcript copies for each 5 × 103 copies of β-actin transcript. Primers used for RSV N-gene and β-actin amplification are described in SI Text.

Cytokine ELISA.

Release of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and TGF-β by DCs was measured 24 h after challenge with RSV or UV-RSV as described in SI Text. Recombinant IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-12 (BD PharMingen) were used as standards for cytokine quantification.

DC Viability and Antigen Presentation Assays.

C57BL/6 bone marrow-derived DCs were prepared as described in ref. 50. On day 5 of culture, DCs were pulsed overnight with RSV or RSV-UV at a moi equal to 1. As a control, DCs were pulsed with same volumes of supernatant from uninfected HEp-2 cultures. After infection, DC viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. Mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLRs) were performed coculturing 1 × 105 or titrated amounts of treated or untreated C57BL/6 DCs with 1 × 105 lymph node cells from BALB/c mice. OT-II T cell cocultures were performed similarly with 1 × 105 cells obtained from transgenic mouse lymph nodes and 20 ng/ml of ovalbumin OVA323–339 peptide (pOVA). IL-2 release was measured after 48 h of DC-T cell coculture as described (26). For IL-10 neutralization assays, cocultures were performed in the presence of 1 μg/ml of neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody (clone JES5–2A5; BD PharMingen). For T cell activation assays with DC-supernatants, 2 × 105 cells were added over ELISA plates (Maxisorb, Nunc) previously coated with increasing amounts of anti-CD3ε antibody (clone 145–2C11; BD PharMingen) in the presence of 100 μl of DC supernatant plus 100 μl of fresh medium and incubated for 24 h. For T cell activation recovery assays, 2 × 105 cells were added over ELISA plates coated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε as described above and incubated for 24 h.

Flow Cytometry.

All flow cytometry analyses were performed on a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). For determination of DC infection with RSV, DCs were pulsed as mentioned above, cultured for 48 h in the presence of RSV, and then double-stained with anti-CD11c-APC (clone HL3; BD PharMingen) and anti-RSV F protein (clone RS-348 kindly provided by Pierre Pothier, Université de Bourgogne) (51). After washing, cells were stained with a goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC (BD PharMingen). DC maturation was determined with fluorescent-labeled antibodies against CD40, CD80, CD86, H-2Kb, and I-Ab, as described (17). Salmonella LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a positive control for DC maturation. Antigen loading on the surface of DCs was assessed with FITC-labeled pOVA (GenScript). For determination of T cell proliferation, mouse lymph nodes were stained with 5 μM CFSE (Invitrogen) for 5 min at 37°C. Then cells were washed and cocultured with DCs as specified above. After coculture, cells were stained with anti-CD4-APC (clone RM4–5; BD PharMingen). Collected data were analyzed by using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). As an alternative to trypan blue staining, cell viability was also assessed by flow cytometry with Sytox blue (Invitrogen).

Laser Confocal Microscopy.

Cells were stained with 0.5 μM CMTMR-Orange or BODIPY 630 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen,) in RPMI medium 1640 (GIBCO, Invitrogen), 5% FBS (Biological Industries) at 37°C for 15 min. T cells were labeled with 1 μM BODIPY FL C5-Ceramide for 30 min (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). DCs (1 × 105) and T cells were seeded into microchambers (Lab-Tek Chamber coverglass, Nalge Nunc) previously coated with polyD-lysine (Sigma). Fluorescence measurements were done on a FluoView FV1000 Confocal Microscope (Olympus). Time-lapse videos (SI Text) and microphotographs were recorded in a 30-min interval. To evaluate IS assembly between T cells and DCs, at least 50 randomly selected fields per treatment were scored visually counting the number of T cells with Golgi apparatus polarized toward DCs within total DC-T cell conjugates. A minimum of 800 conjugates were analyzed per treatment in three independent experiments. ICAM-1 staining was performed as described in SI Text.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical significance of differences between groups was evaluated by unpaired Student's t test by using the GraphPad Prism software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are grateful to Patricia Bustos for technical assistance with cell cultures for RSV propagation. Similarly, we thank Sergio Quezada for assistance with reagents. This work was supported by FONDECYT (Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Cientifico y Tecnológico) Grants 1030557, 1050979, 11075060, and 3070018; SavinMuco-Path-INCO-CT-2006-032296; IFS#B/3764-1; FONDEF D04I1075; and Millennium Nucleus on Immunology and Immunotherapy (P04/030-F). P.A.G. and L.J.C. are fellows from CONICYT (Comisión Nacional de Investigación Cientifica y Tecnológica) Chile.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0802555105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shay D-K, et al. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980-1996. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:1440–1446. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glezen W-P, Taber L-H, Frank A-L, Kasel J-A. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:543–546. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200053026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson F-W, Collier A-M, Clyde W-A, Jr, Denny F-W. Respiratory-syncytial-virus infections, reinfections and immunity. A prospective, longitudinal study in young children. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:530–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903083001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall C-B, Walsh E-E, Long C-E, Schnabel K-C. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:693–698. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng R, et al. Long-lasting balanced immunity and protective efficacy against respiratory syncytial virus in mice induced by a recombinant protein G1F/M2. Vaccine. 2007;25:7422–7428. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voges B, et al. Recombinant Sendai virus induces T cell immunity against respiratory syncytial virus that is protective in the absence of antibodies. Cell Immunol. 2007;247:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawasaki Y, Hosoya M, Katayose M, Suzuki H. Role of serum neutralizing antibody in reinfection of respiratory syncytial virus. Pediatr Int. 2007;46:126–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2004.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGill A, et al. Detection of human respiratory syncytial virus genotype specific antibody responses in infants. J Med Virol. 2004;74:492. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sone S, et al. Enhanced cytokine production by milk macrophages following infection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:630–636. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Bree G-J, et al. Characterization of CD4+ memory T cell responses directed against common respiratory pathogens in peripheral blood and lung. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1718–1725. doi: 10.1086/517612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vallbracht S, Unsold H, Ehl S. Functional impairment of cytotoxic T cells in the lung airways following respiratory virus infections. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1434–1442. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang J, Braciale T-J. Respiratory syncytial virus infection suppresses lung CD8+ T-cell effector activity and peripheral CD8+ T-cell memory in the respiratory tract. Nat Med. 2002;8:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidema J, et al. Human CD8(+) T cell responses against five newly identified respiratory syncytial virus-derived epitopes. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2365–2374. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidema J, et al. CD8+ T cell responses in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infants with severe primary respiratory syncytial virus infections. J Immunol. 2007;179:8410–8417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banchereau J, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itano A-A, Jenkins M-K. Antigen presentation to naive CD4 T cells in the lymph node. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:733–739. doi: 10.1038/ni957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobar J-A, Gonzalez P-A, Kalergis A-M. Salmonella escape from antigen presentation can be overcome by targeting bacteria to Fc gamma receptors on dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:4058–4065. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobar J-A, et al. Virulent Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium evades adaptive immunity by preventing dendritic cells from activating T cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6438–6448. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00063-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raftery M-J, et al. CD1 antigen presentation by human dendritic cells as a target for herpes simplex virus immune evasion. J Immunol. 2006;177:6207–6214. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majumder B, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr impairs dendritic cell maturation and T-cell activation: Implications for viral immune escape. J Virol. 2005;79:7990–8003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.7990-8003.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrow G, Slobedman B, Cunningham A-L, Abendroth A. Varicella-zoster virus productively infects mature dendritic cells and alters their immune function. J Virol. 2003;77:4950–4959. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4950-4959.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Peters N, Schwarze J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells limit viral replication, pulmonary inflammation, and airway hyperresponsiveness in respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:6263–6270. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyer M, et al. Sustained increases in numbers of pulmonary dendritic cells after respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Graaff P-M, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of monocyte-derived dendritic cells decreases their capacity to activate CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:5904–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerrero-Plata A, et al. Differential response of dendritic cells to human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:320–329. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0287OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartz H, Buning-Pfaue F, Turkel O, Schauer U. Respiratory syncytial virus induces prostaglandin E2, IL-10 and IL-11 generation in antigen presenting cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;129:438–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondo Y, et al. Regulation of mite allergen-pulsed murine dendritic cells by respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:494–498. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200305-663OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartz H, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus decreases the capacity of myeloid dendritic cells to induce interferon-gamma in naive T cells. Immunology. 2003;109:49–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chi B, et al. Alpha and lambda interferon together mediate suppression of CD4 T cells induced by respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 2006;80:5032–5040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5032-5040.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlender J, Walliser G, Fricke J, Conzelmann K-K. Respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein mediates inhibition of mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation by contact. J Virol. 2002;76:1163–1170. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1163-1170.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothoeft T, et al. Differential response of human naive and memory/effector T cells to dendritic cells infected by respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:263–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boogaard I, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus differentially activates murine myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunology. 2007;122:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridgway W, Fasso M, Fathman C-G. Following antigen challenge, T cells up-regulate cell surface expression of CD4 in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;161:714–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krieger N-R, Fathman C-G, Shaw M-K, Ridgway W-M. Identification and characterization of the antigen-specific subpopulation of alloreactive CD4+ T cells in vitro and in vivo. Transplantation. 2000;69:605–609. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002270-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore K-W, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman R-L, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang A-S, Lattime E-C. Tumor-induced interleukin 10 suppresses the ability of splenic dendritic cells to stimulate CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2150–2157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barcia C, et al. In vivo mature immunological synapses forming SMACs mediate clearance of virally infected astrocytes from the brain. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2095–2107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzalez P-A, Carreno L-J, Figueroa C-A, Kalergis A-M. Modulation of immunological synapse by membrane-bound and soluble ligands. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grakoui A, et al. The immunological synapse: A molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kupfer A, Singer S-J. Cell biology of cytotoxic and helper T cell functions: Immunofluorescence microscopic studies of single cells and cell couples. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:309–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thoulouze M-I, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type-1 infection impairs the formation of the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2006;24:547–561. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller N, et al. Measles virus contact with T cells impedes cytoskeletal remodeling associated with spreading, polarization, and CD3 clustering. Traffic. 2006;7:849–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho N-H, et al. Inhibition of T cell receptor signal transduction by tyrosine kinase-interacting protein of Herpesvirus saimiri. J Exp Med. 2004;200:681–687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Depoil D, et al. Immunological synapses are versatile structures enabling selective T cell polarization. Immunity. 2005;22:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smit J-J, Rudd B-D, Lukacs N-W. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells inhibit pulmonary immunopathology and promote clearance of respiratory syncytial virus. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1153–1159. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esquerre M, et al. Human regulatory T cells inhibit polarization of T helper cells toward antigen-presenting cells via a TGF-beta-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2550–2555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708350105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carreno L-J, Gonzalez P-A, Kalergis A-M. Modulation of T cell function by TCR/pMHC binding kinetics. Immunobiology. 2006;211:47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haller C, Rauch S, Fackler O-T. HIV-1 Nef employs two distinct mechanisms to modulate Lck subcellular localization and TCR-induced actin remodeling. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robertson J-M, Jensen P-E, Evavold B-D. DO11.10 and OT-II T cells recognize a C-terminal ovalbumin 323–339 epitope. J Immunol. 2000;164:4706–4712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bueno S-M, et al. The capacity of Salmonella to survive inside dendritic cells and prevent antigen presentation to T cells is host specific. Immunology. 2008;124:522–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bourgeois C, et al. Use of synthetic peptides to locate neutralizing antigenic domains on the fusion protein of respiratory syncytial virus. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1051–1058. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-5-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.