Abstract

Naturally acquired immune responses against human cancers often include CD8+ T cells specific for the cancer testis antigen NY-ESO-1. Here, we studied T cell receptor (TCR) primary structure and function of 605 HLA-A*0201/NY-ESO-1157–165-specific CD8 T cell clones derived from five melanoma patients. We show that an important proportion of tumor-reactive T cells preferentially use TCR AV3S1/BV8S2 chains, with remarkably conserved CDR3 amino acid motifs and lengths in both chains. All remaining T cell clones belong to two additional sets expressing BV1 or BV13 TCRs, associated with α-chains with highly diverse VJ usage, CDR3 amino acid sequence, and length. Yet, all T cell clonotypes recognize tumor antigen with similar functional avidity. Two residues, Met-160 and Trp-161, located in the middle region of the NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide, are critical for recognition by most of the T cell clonotypes. Collectively, our data show that a large number of αβ TCRs, belonging to three distinct sets (AVx/BV1, AV3/BV8, AVx/BV13) bind pMHC with equal antigen sensitivity and recognize the same peptide motif. Finally, this in-depth study of recognition of a self-antigen suggests that in part similar biophysical mechanisms shape TCR repertoires toward foreign and self-antigens.

Keywords: antigen recognition, cytolytic T lymphocytes, melanoma, T cell receptors, tumor immunity

The specificity of CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses relies on the interaction of clonotypically distributed antigen receptors (TCR) on the surface of the effector cell with small immunogenic peptide fragments displayed at the surface of a target cell by self-MHC class I molecules (pMHC) (1). Binding of the heterodimeric αβ-chains of the TCR to the pMHC complex is a key step leading to T cell activation and cell killing. The αβ TCRs bind agonist pMHCs with relatively low affinity (Kd ≅1–100 μM) through complementary determining regions (CDR) present on their variable domains (2). The mature TCR repertoire is shaped by both positive and negative intrathymic selection, leading to an estimated 2.5 × 107 different TCR clonotypes in the human peripheral T cell pool (3). A relatively small number of CTL precursor cells is normally selected in response to the antigenic stimulus and comprises cells bearing several TCRs (≈10 to ≈50 clonotypes) differing from each other yet having the ability to recognize the same pMHC complex. The recent development and availability of multimerized MHC–peptide complexes combined to TCR spectratyping with high-throughput DNA sequencing allowed the study of the development of antigen-driven CD8+ T lymphocyte response to chronic antigenic exposure, e.g., in viral infection (CMV, EBV, HIV) or in cancer patients. The impact of TCR diversity on recognition of single antigenic pMHC complexes has been extensively investigated, and the relative contributions of each TCR β-chain have been addressed in several models. In a few systems, strong biases in the TCR repertoire selection of antigen-specific T cells, resulting in the preferential usage of particular αβ TCR combinations, have been reported (4, 5) [supporting information (SI) Text].

Over the last 10 years, 24 class I and class II TCR–pMHC complexes have been crystallized and identified a substantial degree of structural variability in TCR–pMHC recognition (reviewed in ref. 6). In many cases, the TCR Vα interactions with the pMHC seem to predominate and, thus provide some basis for a conserved diagonal orientation of the TCR on the pMHC. Importantly, all aspects of TCR binding to pMHC have direct implications for TCR function. For instance, there is a direct link between peptide–MHC affinity and the efficiency of recognition by CD8+ T lymphocytes (7), as similarly, there is a close relationship between the Kd of the TCR binding and the activity of the T cell in cytolytic assays (8, 9). Nevertheless, despite all of these efforts, the structural bases of TCR repertoire selection for pMHC complexes remain elusive.

The molecular recognition events taking place at the TCR–peptide–MHC interface are of great interest for medical applications. In particular, studies underlying pMHC recognition have important implications for the design of therapeutic antigen-based vaccines or of engineered TCRs. Therefore, the analysis of the primary structure of both α- and β-chains of the TCR, especially when combined with the functional analysis of the corresponding clonal populations of T cells, can provide important insights in TCR repertoire selection in response to a given pMHC ligand (10). Here, we report a detailed and combined molecular and functional characterization of the TCR repertoire specific for the cancer testis (CT) antigen NY-ESO-1157–165 bound to HLA-A*0201, by the analysis of large numbers of T cell clones and TCRs derived from melanoma patients with naturally occurring CD8+ T cell responses.

Results

Naturally Occurring NY-ESO-1157–165-Specific CD8+ T Cell Responses Display a Preferential Usage of BV1, BV8, and BV13 TCRs.

Previous studies have focused much attention on tumor antigens encoded by cancer germ-line genes, whose expression can be found in various types of tumors but not in normal adult tissues, with the exception of testis. In particular, because of its frequent expression in tumors and immunogenicity in advanced cancer patients, NY-ESO-1 is currently viewed as an ideal candidate for therapeutic tumor antigen-based vaccines. Recently, we reported an unusually strong natural tumor-specific immune response against NY-ESO-1157–165 in patient LAU 50 with advanced melanoma (11), characterized by expansions of codominant T cell clonotypes bearing distinct BV1, BV8, or BV13 TCRs (12). These data prompted us to examine the proportion of BV1, BV8, and BV13 TCRs present within NY-ESO-1-specific T cells of peptide-stimulated PBMCs from four additional melanoma patients with naturally occurring NY-ESO-1-specific CTL responses (13). By using HLA-A2/NY-ESO-1157–165 multimers in combination with mAbs directed against the variable region of TCR BV1, BV8, and BV13, we found that the majority of multimer+ T cells expressed TCRs with these BV elements (Fig. S1), in line with a recent report by Le Gal and colleagues (10).

Restricted CDR3β Diversity and High Sequence Homology Among NY-ESO-1-Specific TCRs Bearing the TCR BV8 Gene Segment.

Using an approach that combines flow cytometry based-cell sorting, TCR spectratyping, and sequencing at the single cell level, we recently identified, in a single patient (LAU 50), nine codominant NY-ESO-1-specific T cell clonotypes characterized by distinct BV1, BV8, or BV13 TCRs sequences (12). Extensive studies of their clonal composition revealed a high degree of sequence homology of the NY-ESO-1-specific TCRs bearing the TCR BV8 gene segment (Fig. S2). These data prompted us to examine in great detail 605 NY-ESO-1-specific T cell clones generated in vitro from patients LAU 50, LAU 97, LAU 155, LAU 156, and LAU 198 (Fig. S1). Complete TCR analysis by sequencing allowed the identification of a total of 49 NY-ESO-1-specific clonotypes, classified into BV1 (12 times), BV8 (21 times), or BV13 (16 times) TCR usage (Fig. 1), including the nine characterized clonotypes from patient LAU 50 (12). A striking feature was that, with two exceptions, all BV8-expressing NY-ESO-1-specific clonotypes shared the same relatively short length of the β-chain CDR3 region (7 aa). Moreover, there was a preferential usage of either the BJ1S1 or the BJ2S1 gene segments and a marked conservation of the CDR3 amino acid composition, particularly at positions 3, 6, and 7 with prominent usage of a glycine, a glutamate, and a glutamine residue, respectively. Interestingly, the TCR analysis of BV1- and BV13-specific T cell clones yielded different results. Indeed, despite conserved BV usage, most of these clonotypes used different BJs and different CDR3β loop sequences of highly variable lengths ranging from 6 to 13 aa (Fig. 1).

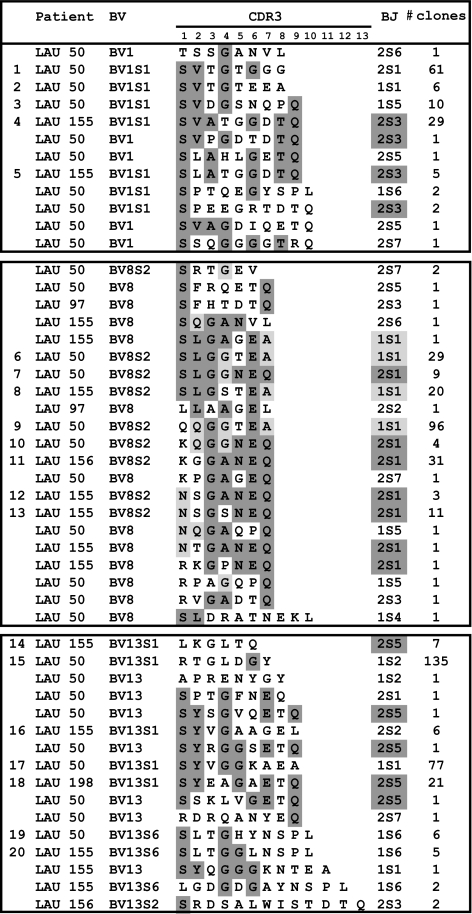

Fig. 1.

Sequence analysis of TCR junctional transcripts derived from BV1+, BV8+, and BV13+ NY-ESO-1157–165 multimer+ T cell clones from five melanoma patients. Transcripts were reverse-transcribed and amplified from multimer+ T cell clones by using either pairs of BV1/BC, BV8/BC, or BV13/BC primers. PCR products were directly purified and sequenced. Conserved residues forming the CDR3 loop and preferential BJ gene element usages are highlighted in gray. The number of in vitro generated T cell clones displaying a given sequence is depicted. Of note, the NY-ESO-1-specific CD8+ T cell response seen in patients LAU 156 and LAU 198 was composed of, respectively, a single dominant BV8 and BV13 T cell clonotype, confirming the results obtained by using anti-BV antibodies and flow cytometry (Fig. S1).

BV8 T Cell Clonotypes Pair with a Highly Restricted Set of Vα-Chains in Contrast to the BV1 and BV13 NY-ESO-1-Specific T Cell Clonotypes.

To assess the full extent of conservation of the primary TCR structure of the BV8 T cell clonotypes, we next examined the TCR α-chain clonal diversity and junctional features of the 20 NY-ESO-1-specific T cell clones defined as dominant clonotypes based on their frequencies, implying that at least three individual T cell clones share the identical TCR β-chain sequence (Fig. 1). Strikingly, sequencing of the complementary TCR α-chains demonstrated the highly recurrent usage of the AV3S1 gene segment by all BV8S2 T cell clonotypes (Fig. 2). Moreover, we observed a marked conservation of the V(D)J junctional sequences and a unique CDR3α length (6 aa) within clonotypes derived from the same and distinct patients. Aside the preferential usage of the AJ31 gene segment, the dominant NY-ESO-1-specific T cell clonotypes were also characterized by their preferred selection of aspartate/leucine at CDR3α positions 1/6, respectively. In sharp contrast, the Vα repertoires associated with both BV1 and BV13 TCRs were highly heterogeneous and comprised various AJs and various CDR3α lengths ranging from 7 to 14 aa (Fig. 2).

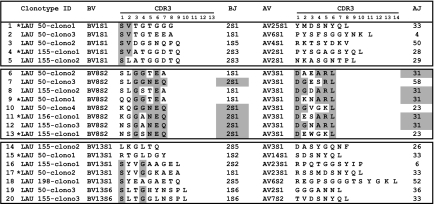

Fig. 2.

Junctional amino acid sequence of TCR α-chains associated with each TCR β transcript derived from dominant NY-ESO-1157–165-specific T cell clonotypes. Conserved residues forming the CDR3α/β loops and preferential AJ/BJ gene element usages are highlighted in gray. *, Clonotypes recently described in ref. 10.

Similar Efficient Tumor Cell Recognition and Killing by NY-ESO-1-Specific T Cell Clones with Distinct Primary TCR Structures.

To evaluate the relationship between the NY-ESO-1-specific T cell clonotypes and functional avidity for antigen recognition, 82 T cell clones generated from patient LAU 50, distributed according to their TCR BV1, BV8, or BV13 clonotypic expression, were assessed in chromium release assays for their ability to recognize graded concentrations of the native NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide pulsed to T2 cells (Fig. 3). Remarkably, most of the BV1-, BV8-, and BV13-derived clonotypes showed similar functional avidity because 50% maximal lysis of T2 cells was found at similar peptide doses (10−9/10−10 M). One exception was BV13 clonotype 2 that exhibited a slightly but statistically significant inferior functional avidity of antigen recognition compared with the other tested clonotypes. Lysis of targets sensitized with an analog peptide with a C to A substitution at peptide position 9 was achieved at ≈1 log lower peptide concentrations (10−10/10−11 M), which corresponds to the increased pMHC stability (14). The ability of the BV1, BV8, and BV13 clonotypes to specifically lyse NY-ESO-1-expressing tumor cell lines revealed that all distinct T cell clonotypes efficiently and similarly recognized the NY-ESO-1-expressing melanoma cell lines Me 275 and Me 290 (Figs. S3 and S4). Altogether, our results demonstrate that T cells bearing three distinct sets of αβ TCRs (AVx/BV1S1, AV3S1/BV8S2, or AVx/BV13) shared similar avidity for antigen recognition and tumor reactivity, irrespective of their BV usage.

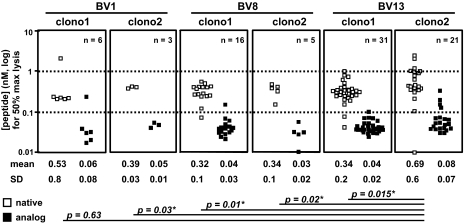

Fig. 3.

Fine specificity of NY-ESO-1 antigen recognition of tumor-reactive T cell clones derived from patient LAU 50. The relative TCR functional avidity was compared by using T2 target cells (HLA-A2+/TAP−/−) pulsed with graded concentrations of either the native NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide (SLLMWITQC) or the analog NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide (SLLMWITQA). Complete collection of data (n = 82 clones) representing the peptide concentration (either native or analog) used to achieve 50% of maximum lysis is shown. Each data point represents the result of an individual clone. Mean ± SD values (nanomolar) are shown. *, P ≤ 0.03 with the Welch two-sample t test.

Both Met and Trp Residues Located in the Middle Region of the Antigenic Peptide Are Critical TCR Contact Residues Regardless of TCR Gene Segment Usage.

To gain information about the specific role of each single amino acid of the NY-ESO-1 peptide in the interaction with well defined TCRs, we analyzed the cytotoxicity of 11 BV1, BV8, and BV13 molecularly defined T cell clonotypes against T2 cells loaded with a set of NY-ESO-1157–165 single alanine-substituted peptide variants. The recognition patterns of each codominant clonotype are depicted in Fig. 4A. The relative antigenic activity was calculated by using the native peptide NY-ESO-1157–165 as reference. As described (13, 14), the peptide with the C165A replacement appeared to be the most efficient antigenic peptide analog, improving HLA-A2 binding and resulting in a marked increase in the recognition by every clonotype. All four BV8 clonotypes exhibited a more homogeneous pattern of fine specificity of recognition compared with the recognition patterns found for BV1 and BV13 T cell clones. Strikingly, several amino acid residues located in the middle region of the antigenic peptide (P3–P8) appeared critical for the recognition by BV1, BV8, or BV13 T cell clonotypes. Both methionine (P4) and tryptophan (P5) residues were particularly crucial for their interaction with the TCR, as demonstrated by the low recognition by all of the BV1, BV8, and BV13 clonotypes for the peptides containing M160A and W161A substitutions (Fig. 4A). Finally, other residues (Leu-P3, Ile-P6, Thr-P7, and Gln-P8) were highly critical for only some but not other clonotypes (either BV1, BV8, or BV13). The contributions of the side chains of the NY-ESO157–165 peptide to the binding free energy of the BV13 clonotype 1 from patient LAU 155 were calculated according to the Molecular Mechanics–Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) approach (Fig. 4B and SI Text) and are in good agreement with the functional recognition pattern found for the same clonotype (Fig. 4A). This particular clonotype was chosen because of the availability of a very closely related TCR–pMHC x-ray structure, designated as the 2BNR complex (15).

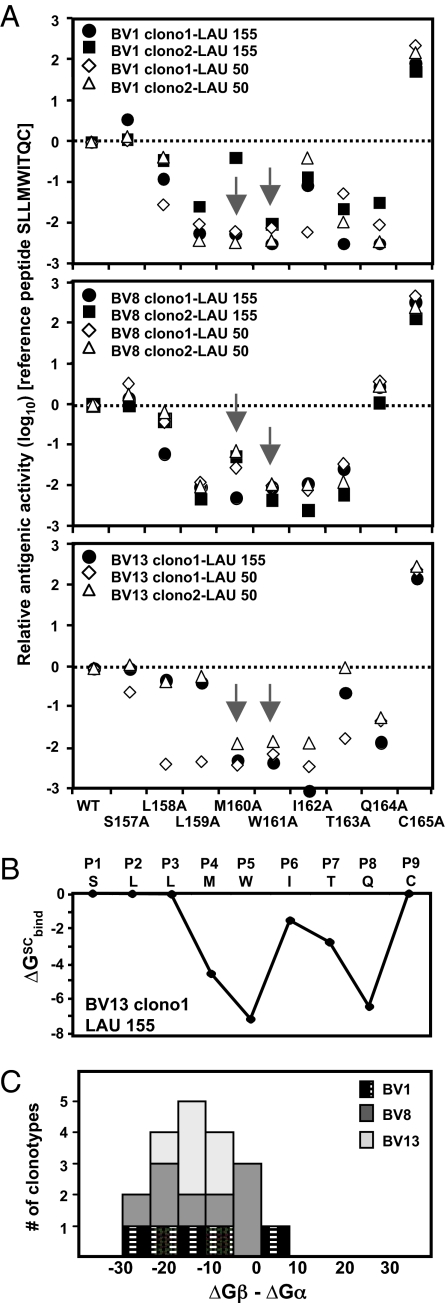

Fig. 4.

Contribution of individual NY-ESO-1157–165 amino acid residues to functional antigen recognition by specific T cell clonotypes. (A) The relative antigenicity of alanine-substituted NY-ESO-1 peptide analogs was assessed on T2 target cells in the presence of graded peptide concentration. We used five and six distinct T cell clonotypes (BV1, BV8, and BV13) isolated from patients LAU 155 and LAU 50, respectively. The molar concentration required for 50% maximal lysis by each T cell clone and for each peptide was calculated from peptide titration experiments. The relative antigenic activity of each peptide analog was determined by using the native peptide NY-ESO-1 as a reference (SI Text). The recognition patterns of BV1-, BV8-, and BV13-derived clonotypes are depicted in separate panels of graphs. (B) Estimation of the binding free energy contributions of each residue of the NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide for the TCR BV13 clonotype 1 isolated from patient LAU 155. Of note, the side chains of the central residues (P4–P8) showed important favorable contributions in the binding between peptide and TCR, whereas the contributions of the outer side chains (P1, P2, P3, and P9) were not significant. (C) Comparison of the sum of the binding free energy contributions made by the TCR Vβ residues and the TCR Vα residues toward the HLA-A*0201/NY-ESO-1157–165 complex. Histogram count of 19 of the 20 TCR models was generated in silico, as a function of the ΔGβ,bind − ΔGα,bind difference. The ΔGβ,bind − ΔGα,bind difference is in kilocalories per mole. Of note, the 2BNR (15) ΔGβ,bind − ΔGα,bind difference was −6.4 kcal/mol, conferring again a preponderant role to the β-chain in the binding process.

Prevalent Contribution of the TCR β-Chain for the Binding Free Energy Toward the NY-ESO-1157–165/HLA-A*0201 Complex.

The in silico modeling of the TCR–pMHC was performed for the 20 dominant NY-ESO-1-specific T cell clonotypes. For each model and for the 2BNR structure (15), we calculated side chains and backbone contributions to the binding free energy made by the TCR residues (SI Text). Fig. 4C shows a histogram count of the models, as a function of the ΔGβ,bind − ΔGα,bind difference. Except for BV1-clono2 (LAU 155) TCR, a large majority of models showed a preferential β-chain contribution (i.e., a negative ΔGβ,bind − ΔGα,bind difference), revealing its greater importance compared with the α-chain, in the binding with NY-ESO peptide and MHC complex.

Discussion

In the present work, we performed a detailed analysis of primary structure and function of the TCR αβ repertoire toward the immunodominant HLA-A2/NY-ESO-1157–165 epitope. The analysis of a large number of T cell clones (605 clones) showed that an important proportion of tumor-reactive CD8+ T lymphocytes preferentially expressed the TCR AV3S1-BV8S2 chains with a remarkably high degree of conservation of CDR3α and β domains, in terms of both length and amino acid composition at certain positions. These data are further emphasized by the comparable recognition patterns of fine specificity exhibited by distinct AV3/BV8 T cell clonotypes, as revealed by the experiments using a set of single alanine-substituted NY-ESO-1 peptides. Collectively, this report demonstrates that similarly to the CD8+ T cell responses observed against viral influenza A matrix protein and EBV EBNA3 epitopes (4, 5), highly restricted and conserved TCR αβ usage can also be observed in CTL responses toward self/tumor antigens such as NY-ESO-1.

Another major finding is that besides the selected AV3S1/BV8S2 set of T lymphocytes, NY-ESO-1-specific TCR repertoires were biased toward the usage of BV1 and BV13 gene segments. However, in contrast to the AV3S1/BV8S2 set, the BV1 and BV13 TCR sets revealed corresponding Vα repertoires of high diversity. Overall, these TCR α-chains were characterized by different Vα and Jα usage of highly variable CDR3 length and amino acid composition. Similar to our data, a recent study showed that CTL specific for the protective immunodominant nucleoprotein epitope (NP366–374) of influenza A viruses in B6 mice used a highly restricted Vβ repertoire but no conserved Vα repertoire (16). Despite the limited set of human T cell clones analyzed, similar conclusions were reached by another study based on HIV-specific CTL responses from long-term survivors (17). Altogether, these observations reveal an unsuspected diversification of the TCR αβ repertoire, which would have been qualified as “highly restricted” had such analyses remained limited to the TCR β-chain repertoire. Therefore, TCR repertoire studies need to include the characterization of both TCR α- and β-chains and not only the latter as done in the majority of previous studies.

Because NY-ESO-1-specific T cells expressed biased TCR BV1 and BV13 chains but can use a variety of TCR α-chains, our data suggest that recognition of the NY-ESO-1157–165/HLA-A*0201 complex may predominantly depend on the TCR β-chain. In this regard, the in silico modeling of the NY-ESO-1-specific T cell repertoire combined with the MM-GBSA decomposition of the binding free energy into TCR α and β contributions revealed that a large majority of specific T cell clonotypes have a preferential β-chain contribution to the TCR–pMHC binding compared with their corresponding α-chain. Collectively, our finding emphasizes the prevalent role of the β-chain in contributing to more favorable interactions with the pMHC ligand than the α-chain. Curiously, the results described here and in the above-mentioned studies do not exactly recapitulate those found by others that rather suggest a predominant role of TCR α-chain in determining the preimmune repertoire of antigen-specific T cells (18–20). In line with this view, Yokosuka et al. (18) have investigated the potential spectrum of TCR αβ-chains to exhibit antigen specificity by systematically analyzing hundreds of individual TCR αβ pairs for antigen-specific recognition. Their findings show that to recognize the HIVgp160 peptide/H-2Dd complex, CTLs have to possess a single TCR α-chain but can use a variety of TCR β-chains. Restricted α-chain usage (i.e., Vα2.1) was also found among HLA-A2/Melan-A specific T cells (19, 20). Consistent with these results, Miles et al. (21) have recently shown that MHC restriction in the CD8+ T cell response to an epitope from EBV, which is naturally immunogenic across two human MHC class I alleles, can be controlled exclusively by TCR α-chain usage.

Many self-antigens are expressed in the thymus (22), associated with negative selection of T cells expressing specific TCRs, in some instances explaining why self/tumor antigen-specific TCRs are of lower avidity as opposed to pathogen-specific TCRs (2). For example, the self/tumor antigen Melan-A/MART-1 is recognized by relatively low avidity TCRs, and these TCRs present higher degrees of TCR β-chain heterogeneity (23). Although avidities of the HLA-A2/NY-ESO-1 specific TCRs are somewhat higher, they still do not reach the high avidities observed among virus-specific TCRs. Nevertheless, the majority of HLA-A2+ individuals are capable of mounting vigorous CD8 T cell responses to this antigen, confirming that it is a preferential target of tumor-specific T cells. Thus, one could speculate that the TCR repertoire studied here is not (much) impaired by thymic negative selection. The question remains open whether similar observations as shown here for NY-ESO-1-specific TCRs can be made for TCRs specific for other self/tumor antigens.

What remains intriguing, at present, is which biophysical mechanisms allow TCRs that either display highly conserved Vα- and β-chains or semiconserved Vβ-chains pairing with complementary diverse Vα-chains, to recognize the same pMHC complex. Despite the 24 solved structures of TCRs–pMHC complexes (6), many of the structural principles that govern MHC restriction still remain unclear. The crystal of the influenza MP58–66/HLA-A2-specific TCR AV10S2/BV17 provides some structural explanations for the specific contribution of BV17 (24). Indeed, the distinctive orientation of this TCR, which is almost orthogonal to the peptide-binding groove of HLA-A2, facilitates insertion of a conserved arginine in the Vβ CDR3 into a notch between the bound peptide and the MHC α2-helix. This unusual interaction may compensate for the lack of prominent side chains of the Flu-peptide pointing toward the TCR (25). Further insights in the comparison of reported TCR–pMHC crystal structures reveal that TCR binding generally occurs in a flexible diagonal orientation to the long axis of the MHC peptide-binding groove (6). Class I MHC molecules usually bind peptides of 8–10 residues in length (on average 9 mers defined as P1–P9) in an extended conformation in which the peptide is fixed at its ends by pockets formed by the MHC molecule. In contrast, the centrally located peptide residues exhibit upward-pointing amino acid side chains that often interact directly with TCR CDR3 loops (6).

Because the NY-ESO-1/A2 complex preferentially selects and binds to (i) conserved AV3S1/BV8S2 and (ii) semiconserved AVx/BV1 and AVx/BV13 TCRs, this antigenic model provides us with the unique opportunity to examine in detail the biophysical nature of distinct TCRs recognizing the same pMHC ligand and the impact of each TCR α- and β-chain on such recognition. Our functional data, using a panel of NY-ESO-1157–165 single alanine-substituted peptide variants, revealed the critical role played by two central residues, Met-P4 and Trp-P5, for the antigenic recognition by different T cell clonotypes. The work reported here confirms and further extends the results obtained from the crystal structure of the 2BNR complex, indicating that binding of the TCR centers on two prominent side chains of the two central amino acids, methionine–tryptophan (15), forming a predominant hot spot interacting with the CDR3α and β loops (26). Because our observations were made on an extended pool of dominant T cell clonotypes isolated from two different patients (LAU 50 and LAU 155), they indicate that this represents a general feature, i.e., that distinct TCRs (AVx/BV1, AV3S1/BV8S2, AVx/BV13) share comparable peptide recognition patterns, suggesting conserved binding modes of distinct A2/NY-ESO-1 specific TCRs. In particular, preliminary observations on in silico models suggest that some conformational motifs within the CDR3β loop may be critical for the binding to the NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide (data not shown). The issue of which residues within the CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3 α and β loops present dominant contributions to (i) antigen recognition and (ii) MHC recognition deserves additional studies combining detailed structural and functional investigations.

A better understanding of structural principles that govern TCR recognition is essential to promote research and clinical applications. The quality of TCRs recruited during disease, or by vaccination, dominantly influences the potency of immune responses (27). To improve therapeutic immune interventions, TCRs need to be fully characterized, and the mechanisms for their recruitment and function must be elucidated. Results from such studies impact, e.g., on the design of antigens for vaccination and on the choice of optimal TCRs for adoptive T cell therapy, with or without TCR gene transfer. Here, we show that the TCR β-chain, comparable with the TCR α-chain in other models, may play an important role in the recognition of pMHC complexes and that depending on the pMHC model, each chain may present dominant contributions to antigen recognition. In addition, similar mechanisms may control TCR repertoire shaping toward foreign or self-antigens because the predominant contribution of the TCR α- or β-chain can be observed under various physiopathological contexts, e.g., acute or chronic in vivo triggering by either viral or tumor antigens. Finally, our data demonstrate that three distinct sets of TCRs (AVx/BV1, AV3/BV8, and AVx/BV13) are able to recognize the same NY-ESO-1/MHC complex with comparable and high functional avidity, conferring successful tumor recognition.

Materials and Methods

Patients, Cell Preparation, and Flow Cytometry.

Five HLA-A*0201 melanoma patients (LAU 50, LAU 97, LAU 155, LAU 156, and LAU 198) provided written informed consent and thus participated in this study of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (LICR) and of the Multidisciplinary Oncology Center, which was approved by Institutional Review Boards and the LICR Protocol Review Committee. Samples were collected and processed for peptide stimulation experiments and for HLA-A2/peptide multimer staining as described in the SI Text.

Generation of T Cell Clones and Functional Cytolytic Assays.

Multimerpos CD8pos T cells were sorted in a FACSVantage SE machine (Becton Dickinson) and cloned by limiting dilution and expanded as described in the SI Text. The functional avidity of antigen recognition was analyzed for in vitro generated T cell clones, isolated from patients LAU 50 and LAU 155, and bearing molecularly defined αβ TCR clonotypes as detailed in the SI Text.

TCR-BV and -AV Repertoire Analysis.

TCR-BV and -AV repertoire analysis was performed after spectratyping, sequencing, and clonotyping as detailed in the SI Text.

Binding Free Energy Calculations.

The estimation of the binding free energy contributions of each residue of the NY-ESO-1 peptide to the TCR–pMHC association was performed on the TCR BV13 clonotype 1 from LAU 155, which is highly related to the TCR AV23-BV13 (1G4) bound to NY-ESO-1157–165/HLA-A*0201 (15), as described in the SI Text.

Computational TCR Modeling.

To calculate the binding free energy contributions made by the TCR Vα and Vβ residues, homology models of the variable domain of the TCR bound to the SLLMWITQC peptide presented by HLA-A*0201 were built by using Modeler 6v2 (28), based on the 2BNR complex (15) and other crystal structures of TCR from the Protein Data Bank (SI Text).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We acknowledge our patients for active participation and the hospital staff for excellent collaboration. We thank J.-C. Cerottini, V. Jongeneel, D. Kuznetsov, S. Leyvraz, D. Liénard, D. Rimoldi, C. Servis, B. Stevenson, and V. Voelter for collaboration and advice; E. Devevre for cell sorting; and I. Luescher and P. Guillaume (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Lausanne, Switzerland) for multimers. We also thank the excellent technical and secretarial help of P. Corthesy-Henrioud, C. Geldhof, R. Milesi, D. Minaïdis, N. Montandon, and M. van Overloop. This work was sponsored and supported by the Swiss National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) in Molecular Oncology, the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, the Cancer Research Institute, New York, and Swiss National Science Foundation Grants 3100A0-105929 and 3200B0-107693. P.R. was supported by the European Union FP6 Cancer Immunotherapy Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0807954105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature. 1974;248:701–702. doi: 10.1038/248701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Merwe PA, Davis SJ. Molecular interactions mediating T cell antigen recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:659–684. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikolich-Zugich J, Slifka MK, Messaoudi I. The many important facets of T cell repertoire diversity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:123–132. doi: 10.1038/nri1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss PA, et al. Extensive conservation of α- and β-chains of the human T cell antigen receptor recognizing HLA-A2 and influenza A matrix peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8987–8990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argaet VP, et al. Dominant selection of an invariant T cell antigen receptor in response to persistent infection by Epstein–Barr virus. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2335–2340. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudolph MG, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. How TCRs bind MHCs, peptides, and coreceptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:419–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sette A, et al. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1994;153:5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valmori D, et al. Vaccination with a Melan-A peptide selects an oligoclonal T cell population with increased functional avidity and tumor reactivity. J Immunol. 2002;168:4231–4240. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.4231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuball J, et al. Cooperation of human tumor-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after redirection of their specificity by a high-affinity p53A2.1-specific TCR. Immunity. 2005;22:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Gal FA, et al. Distinct structural TCR repertoires in naturally occurring versus vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell responses to the tumor-specific antigen NY-ESO-1. J Immunother. 2005;28:252–257. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000161398.34701.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgaertner P, et al. Ex vivo detectable human CD8 T cell responses to cancer-testis antigens. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1912–1916. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derre L, et al. In vivo persistence of codominant human CD8+ T cell clonotypes is not limited by replicative senescence or functional alteration. J Immunol. 2007;179:2368–2379. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valmori D, et al. Naturally occurring human lymphocyte antigen-A2 restricted CD8+ T cell response to the cancer testis antigen NY-ESO-1 in melanoma patients. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4499–4506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero P, et al. CD8+ T cell response to NY-ESO-1: Relative antigenicity and in vitro immunogenicity of natural and analogue sequences. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:766s–772s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JL, et al. Structural and kinetic basis for heightened immunogenicity of T cell vaccines. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1243–1255. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong W, et al. CTL recognition of a protective immunodominant influenza A virus nucleoprotein epitope utilizes a highly restricted Vβ but diverse Vα repertoire: Functional and structural implications. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong T, et al. HIV-specific cytotoxic T cells from long-term survivors select a unique T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1547–1557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokosuka T, et al. Predominant role of T cell receptor (TCR) α-chain in forming preimmune TCR repertoire revealed by clonal TCR reconstitution system. J Exp Med. 2002;195:991–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trautmann L, et al. Dominant TCR Vα usage by virus- and tumor-reactive T cells with wide affinity ranges for their specific antigens. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3181–3190. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3181::AID-IMMU3181>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich PY, et al. Prevalent role of TCR α-chain in the selection of the preimmune repertoire specific for a human tumor-associated self-antigen. J Immunol. 2003;170:5103–5109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miles JJ, et al. TCR α genes direct MHC restriction in the potent human T cell response to a class I-bound viral epitope. J Immunol. 2006;177:6804–6814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taubert R, Schwendemann J, Kyewski B. Highly variable expression of tissue-restricted self-antigens in human thymus: Implications for self-tolerance and autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:838–848. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietrich PY, et al. Melanoma patients respond to a cytotoxic T lymphocyte-defined self-peptide with diverse and nonoverlapping T cell receptor repertoires. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2047–2054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart-Jones GB, McMichael AJ, Bell JI, Stuart DI, Jones EY. A structural basis for immunodominant human T cell receptor recognition. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:657–663. doi: 10.1038/ni942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogsgaard M, Davis MM. How T cells “see” antigen. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:239–245. doi: 10.1038/ni1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sami M, et al. Crystal structures of high-affinity human T cell receptors bound to peptide major histocompatibility complex reveal native diagonal binding geometry. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2007;20:397–403. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallimore A, Dumrese T, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Rammensee HG. Protective immunity does not correlate with the hierarchy of virus-specific cytotoxic T cell responses to naturally processed peptides. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1647–1657. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.